Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to highlight the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the practice of orthopaedics in Greece and Cyprus.

Methods

The survey used the online questionnaire from AGA (Gesellschaft für Arthroskopie und Gelenkchirurgie; Society for Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery) to facilitate the comparison between different European countries. The questionnaire was distributed online to members of the HAOST (Hellenic Association of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma), the ΟΤΑΜΑΤ (Orthopaedic and Trauma Association of Macedonia and Thrace) and the CAOST (Cypriot Association of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma). The questionnaire consisted of 29 questions, which included demographic data, questions on the impact of the pandemic on the practice of orthopaedic surgery and questions on the impact on the personal and family life of orthopaedic surgeons.

Results

The questionnaire was sent to 1350 orthopaedic surgeons in Greece and Cyprus, 303 of whom responded (response rate 22.44%). 11.2% of the participants reported cancellation of overall orthopaedic procedures. According to 35.6–49.8% of the participants, arthroscopic procedures were continued. As regards elective primary arthroplasties, 35.3% of the participants reported that these continued to be performed at their hospitals. Post-operative follow-ups as well as physiotherapy were affected by the pandemic, and changes were also observed in the habits of orthopaedic surgeons in their personal and family lives.

Conclusion

The orthopaedic service in Greece and Cyprus decreased during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Arthroscopic procedures and total joint replacements decreased significantly, but not to the same extent as in other countries. Health systems were not fully prepared for the first wave of the pandemic and the various countries took social measures at different times and to different extents. Thus, studying the impact of the pandemic on the practice of orthopaedic surgery in different countries can help health systems to better prepare for future pandemics; public health can then be shielded and hospitals can continue to provide high-quality orthopaedic care.

Level of evidence

Level V.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A novel coronavirus strain, known as SARS-CoV-2, initiated an outbreak in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. This epidemic quickly spread throughout the globe and on 11.03.2020 the World Health Organization classified the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic [9].

To optimise their management of the pandemic, countries changed their health policies and hospitals modified the provision of their services.

In the surgical sector, many surgical departments reported a decrease in the number of operations performed, as fewer beds were available in intensive care units as well as in clinics, as these had been allocated to COVID-19 patients [4].

The orthopaedic departments, as a functional part of the hospitals, were required to change the schedule of their operations and outpatient clinics, to allow material and human resources to be used in other departments. In the USA, the AAOS (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons) issued guidelines and protocols on the management of orthopaedic patients [22]. At a global level, studies on the operation of orthopaedic departments report a reduction in the number of scheduled operations and a change in the outpatient services provided. Orthopaedic surgeons were also assigned to work in areas outside orthopaedic care [20, 32].

However, the curve of COVID-19 cases in each country reached its peak at different times, so that different health policies were adopted at different stages, which led to different impacts on the operation of hospitals and orthopaedic departments [27].

Thus each country is unique, as the function of the health system and consequently of the orthopaedic departments can help in the emergence of policies, measures and practices to better prepare for possible new waves of the pandemic and potentially for future pandemics.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, and following the confirmation of the first three cases, the Greek authorities proceeded from 27.02.2020 to close schools and to suspend cultural events. From 16.03.2020, all retail shops were closed and all services in all areas of religious worship were suspended nationwide, except for food stores and pharmacies. From 19.03.2020, all international flights were cancelled and from 22.03.2020, nationwide restrictions in movement were imposed, except for important reasons. From 04.05.2020 and after 42 days of full lockdown, the Greek authorities gradually lifted the restrictions in movement and business activity gradually resumed. The measures implemented at the transnational level included mandatory isolation of travellers for 14 days. Visitors were initially only accepted from EU countries. However, a limited number of tourists were subsequently accepted from non-EU countries. Specific gates of entry into the country were designated and diagnostic tests were performed before arrival in Greece. Within Greece, the numbers of customers in cafes and restaurants were initially restricted, social distancing was enforced and masks were compulsory. As the situation improved, more customers were allowed into shops, but the working hours of shops were reduced and only open areas were allowed to operate. The restrictions in Cyprus were similar to those in Greece [1]. The measures taken in Greece were among the most proactive and stringent in Europe, as the choice of measures by the government was based mainly on scientific epidemiological data from the pandemic and on the recommendations of a committee of expert scientists [14]. They contributed significantly to the containment of the pandemic and assured that the numbers of confirmed cases and deaths in Greece and Cyprus were among the lowest in Europe during the first wave of the pandemic (Fig. 1) [7, 12, 26].

Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases among different European countries [28]

The present work is important because, on the one hand, there are no previous studies in Greece and Cyprus, which study the impact of the pandemic on the practice of orthopaedic surgery, and on the other hand, it shows how two countries in which the health care systems were significantly weakened by the economic crisis of 2008 dealt with the pandemic. The results of this study can be the subject of future studies to adequately prepare potentially vulnerable health systems against pandemics to maintain the provision of effective health services in the field of orthopaedic surgery.

Materials and methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the scientific committee of the 1st University Orthopaedic Clinic of Attikon Hospital (ID: 12/03.04.2022/1st Orthopaedic Clinic/Attikon University Hospital). The participation of orthopaedic surgeons was on a voluntary basis. The survey ran from April 2020 to August 2020 and covered the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Absolute (N) and relative frequency (%) were used to describe the qualitative variables. The SPSS® statistical package (Version 22, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis and presentation of results.

The questionnaire was completed and submitted electronically by 303 orthopaedic surgeons from Greece and Cyprus (response rate 22.44%). Τhe majority were men, and 287 (94.7%) and 189 (62.3%) participants were older than 40 years old. When participants were asked about their marital status, 217 (71.6%) said they were married and 9 out of 10 reported having at least one child. As regards their level of education, 130 (42.9%) participants stated that they had only a medical school degree (MD), 36 (11.9%) and 137 (45.2%) that they had also received a master of science postgraduate degree (MSc) or a doctorate (PhD), respectively, and 93 (30.7%) stated that they had successfully completed a sub-specialisation fellowship training programme (Table 1).

The survey used a questionnaire composed by the AGA (Society for Arthroscopy and Joint Surgery; Gesellschaft für Arthroskopie und Gelenkchirurgie) to facilitate the comparison among different European countries [20]. The original questionnaire from the AGA contained 20 questions. To these were added nine other questions which related to demographic data. The final distributed questionnaire consists of 29 single/multiple choice questions, divided into three categories. The first category contains questions related to demographic data, such as gender, age, marital status, number of children, educational level, job position, region of work, specialisation, hospital of orthopaedic practice and years of medical practice (ten questions). The second category includes questions about the impact of the pandemic on work practices as well as the personal lives of orthopaedic surgeons. In particular, it includes questions relating to the fear of contaminating relatives and their approach to prevention, the impact of the pandemic on individual orthopaedic practice and—on the personal level—their estimate as to how long their orthopaedic practice would be affected by the pandemic, personal quarantine and the impact on personal income (seven questions). Finally, participants were asked to delineate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their department, in terms of the extent of the effect on the department, the impact on outpatient consultations, impact on elective and emergency surgeries, training on COVID-19, incidence of positive cases in their department, possible shortages, changes in daily orthopaedic reports, preventive measures in the department, telemedicine practices, impact on post-operative controls, impact on physiotherapy, as well as current status of the department (12 questions).

The questionnaire was distributed prospectively (via Google Forms online platform) to members of the HAOST (Hellenic Association of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma), the ΟΤΑΜΑΤ (Orthopaedic and Trauma Association of Macedonia and Thrace) and the CAOST (Cypriot Association of Orthopaedic Surgery and Trauma).

With respect to the job characteristics of the participants, one in three ran a private practice office, while one in five was either in an orthopaedic residency programme or working as a junior consultant (Grad B) at a hospital. The majority of participants were working at a public hospital, followed by those running a private practice office. With respect to their active service as healthcare providers, seven out of ten participants declared that they had worked actively as medical doctors for at least 10 years. The majority of participants reported receiving specific training on COVID-19 (Table 2). In terms of their main field of practice, the majority of participants stated that it was “traumatology”, followed by “knee surgery” and “general orthopaedics” (Fig. 2).

The vast majority of the participants, 294 (97%) practised orthopaedic surgery in Greece and the remaining 9 (3%) in Cyprus. In Greece, 83 (28.4%) participants were based in the Municipality of Attica, whereas 83 (28.4%) were located in the Municipality of Thessaloniki. In Cyprus, the majority of doctors practised orthopaedic surgery in Nicosia.

Results

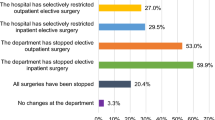

As regards the impact of the pandemic on the provision of orthopaedic care, 34 (11.2%) reported that all procedures were completely cancelled. Furthermore, 149 (49.2%) participants reported that only elective inpatient procedures were cancelled. As regards the outpatient clinics, 94 (31%) reported that only patients with an acute orthopaedic problem were allowed to be seen. Regarding daily work, 221(72.9%) reduced their surgical work, whereas 50 (16.5%) engaged in administrative work and 61 (20.1%) were assigned to non-orthopaedic care positions (Table 3).

Apart from the implications for personal practice, the COVID-19 pandemic also impacted the function of orthopaedic clinics and departments. As far as traumatology is concerned, the majority of participants reported that the surgical treatment for acute fractures of the upper and lower extremities continued to be provided by their healthcare institutions. In particular, operations relating to osteosynthesis of femoral shaft fractures (85.5%) and osteosynthesis of femoral neck fractures (84.8%) also continued to be performed. However, there was a significant cutback in many elective operations. As regards different arthroscopic procedures, only 35.6–49.8% of the participants reported that they continued to be performed. Higher percentages were reported for the knee joint and lower for the shoulder and hip. Similar cutbacks were mentioned for “elective” total arthroplasties, since only 35.3% of the participants continued to perform these at their institution. The participants also confirmed high rates of cancellation (up to 31.7%) or postponement (up to 25.4%) for metalwork removals and correction for leg length discrepancy (Table 4, Fig. 3). As regards post-operative checks, at least seven out of ten participants reported that they continued to perform clinical, radiological checks and suture removal (Table 5).

As regards physiotherapy, about one in two participants reported that patients could have physiotherapy post-operatively. Only a small percent mentioned that professional physiotherapy was not provided in any form (Table 6). Concerning professional meetings, the majority of participants reported that everyone could participate by taking protective measures (e.g. masks), while in one in ten cases the meetings were held online as video conferences (Table 7). With regard to telemedicine services, the majority participants stated that services were offered via telephone, followed by video-conferencing platforms (Table 8).

Moreover, the majority of participants reported that they were more careful at work than usual, washing and disinfecting their hands more often than usual. At home, one in five tried to keep a distance from their family, while 36 avoided physical contact with family members/people in the same household (Table 9, Fig. 4).

Discussion

It is important to study the impact of pandemic COVID-19 on the practice of orthopaedics during the first wave of the pandemic, as health systems were not fully prepared at the start of the pandemic and there were no specific vaccines and only limited options in drug therapy. During this period, different countries took social measures (e.g. lockdowns) at different times and to different extents. The measures taken in Greece and Cyprus were among the most proactive and stringent in Europe and they led significantly to the containment of the pandemic, keeping the number of confirmed cases and deaths in the country among the lowest in Europe (Fig. 1) [7, 12, 26].

The most important findings of the present study were that in Greece and Cyprus during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, most trauma operations continued to be performed, while scheduled orthopaedic operations were often either cancelled or postponed. However, the reported reduction in elective procedures was not to the same extent as reported in other studies. Many orthopaedic surgeons in both countries (11.2%) reported that all procedures were cancelled. Interestingly, in a similar study in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, a far larger percentage of orthopaedic surgeons (20.4%) reported that all procedures were cancelled. In this study in German-speaking countries during the first wave of the pandemic, only 10–30% of participants reported continuation of arthroscopic procedures, 6.2% reported that they were still performing elective total joint arthroplasty and 11.8% continued with aseptic revisions of arthroplasties [20]. A US study of Medicare beneficiaries reported a reduction of primary TKA and THA without fracture to 94 and 92%, respectively, by the end of March 2020 in comparison with that previously [6]. In a survey, the American Association of Hip and Knee Orthopedic Surgeons (AAHKS) estimates that hospitals stopped 92% of all elective surgeries [3]. However, a study from Hong Kong reports, for the period January to June 2020, a 53% reduction in elective joint replacement operations [17].

As far as soft tissue operations were concerned, 25% reported that they had continued with reconstructions of the anterior cruciate ligament, while 44.1% had cancelled repairs of the rotator cuff [20]. In another European survey, only 5.9% of participants continued with primary total joint arthroplasties and 3.8% still performed aseptic revisions. On the other hand, trauma operations largely continued, as did periprosthetic fractures, femoral neck fractures and septic revision for acute infections [32]. Patients with fractures, besides not being able to delay operation beyond a reasonable duration, however, may be at higher risk of COVID-19 pneumonia [23]. In the UK, 91% of orthopaedic surgeons reported cancellation of elective operations and 70% reported that trauma cases continued to be operated on, but at a reduced capacity [15].

Delaying or cancelling interventions has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life [29], social distress [16] as well as pain tolerance [11] and the poor outcome of the interventions themselves when they are finally performed [24]. Due to cancellations and postponements of elective surgeries, the number of orthopaedic patients waiting for surgery has increased significantly. Hospitals should, once conditions improve, implement targeted measures to prioritise and quickly and efficiently manage pending elective surgeries [10]. It is considered imperative that femoral neck fractures, periprosthetic fractures, and acute infections should be given priority as soon as conditions permit [33].

Two other parameters in orthopaedic care that have been affected by the pandemic are the availability of physiotherapy and post-operative checks. However, while in the present study about 50% of participants reported that physiotherapy continued, in other European surveys the percentages were 16.5–35.1%. A promising alternative to face-to-face physiotherapy is telerehabilitation [18] with good results for common musculoskeletal problems [5]. At the same time, telerehabilitation is effective for elderly people with fragility fractures, as it increases mobility and autonomy, while reducing the likelihood of a respiratory infection from a visit to the hospital or rehabilitation centre [8, 19]. Post-operative follow-ups continued as normal, according to 77.2% of participants, while in other surveys they continued without problems, according to 31.6–57.1% of participants [20, 32]. In the UK, 38% of participants reported that scheduled outpatient appointments continued, but at a reduced rate [15]. ESSKA issued guidelines urging follow-ups to be done in the early post-operative period to detect potential COVID-related complications and where appropriate to use videoconference to limit patient displacement [25].

Training in orthopaedic clinics ceased and orthopaedic surgeons were either assigned to posts of non-orthopaedic patient care or carried out administrative work [20, 32].

Telemedicine has long been established as an effective way of examining patients without significant adverse effects [30]. The pandemic has led to greater utilisation of telemedicine for orthopaedic follow-ups [13, 31]. In the present study, 30.7% of participants reported using video conferencing, while 54.5% reported making a phone call. The same communication methods were adopted in the UK, in order to reduce the need for hospital follow-ups [15]. Telemedicine is particularly useful in clarifying patient questions, monitoring wounds, assessing the range of motion, evaluating medical images and documents, sending electronic prescriptions and educating the patient with audio-visual material [2]. However, effective use of telemedicine necessitates an awareness, access to computers and literacy with their use [21].

The pandemic also affected orthopaedic surgeons’ behaviour and habits, both in their personal and family lives [34]. They confirmed that they were more careful at their workplace (89.2%) and washed and disinfected their hands more often (84.2%). Similar high percentages were reported by Liebensteiner MC et al. (2020)—74.2 and 81%, respectively. Distancing from the family at home (20.1%) and avoiding physical contact with other family members (11.9%) were reported as preventive measures. Thaler M et al. (2020) reported similar percentages (21.3 and 22.6%, respectively), whereas Liebensteiner MC et al. (2020) reported percentages of 13.2 and 8.6%, respectively.

A limitation of our study is that the findings included orthopaedic surgeons working in Greece and Cyprus and may not be generalised for other countries with different health-care systems. However, countries with weakened health systems may benefit from the findings of this study to prepare accordingly for future pandemics. Moreover, some studies with which this research was compared, were performed in specific orthopaedic sub-groups (e.g. restricted to participants with an interest in arthroscopy or total joint arthroplasties). On the contrary, a strength of our study is that orthopaedic surgeons from all sub-specialities were included and therefore the study population is a representative sample of the impact of the pandemic on all different orthopaedic procedures. One essential point of the study is that during the period between April and August 2020, Greece and Cyprus had among the lowest levels of confirmed cases and deaths in Europe. This was due to the preventive and tough social measures to contain the pandemic. The survey employed the same questionnaire on orthopaedic care as in other European surveys and for the same time period and showed that in Greece and Cyprus there were decreases in the numbers of arthroscopic and arthroplasty procedures—as reported in other European countries—but these were less severe and extensive. Therefore, provision of planned orthopaedic care to orthopaedic patients was generally maintained in Greece and Cyprus.

Conclusions

Although the provision of elective orthopaedic operations in Greece and Cyprus decreased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the impact was less severe during the first wave than in other European countries. Early adoption of extensive social measures against the pandemic may allow health systems to continue the provision of orthopaedic care to patients.

References

A3M Global Monitoring GmbH (2022) COVID-19 pandemic–Greece. In: A3M Event page. https://global-monitoring.com/gm/page/events/epidemic-0001942.ugWbZWZFtsIc.html?lang=en. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Abolghasemian M, Ebrahimzadeh M, Enayatollahi M, Honarmand K, Kachooei Α, Mehdipoor S, Mortazavi M, Mousavian A, Parsa A, Akasheh G, Bagheri F, Ebrahimpour A, Fakoor M, Moradi R, Razi M (2020) Iranian Orthopedic Association (IOA) Response Guidance to COVID-19 Pandemic April 2020. Arch Bone Jt Surg 8:209–217. https://doi.org/10.22038/ABJS.2020.47678.2370

American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (2020) AAHS Members Survey on COVID-19 Impact. In: AAHKS Weekly News Update. https://www.aahks.org/aahks-surveys-members-on-covid-19-impact/. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Angelico R, Trapani S, Manzia TM, Lombardini L, Tisone G, Cardillo M (2020) The COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: initial implications for organ transplantation programs. Am J Transplant 20:1780–1784. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15904

Azhari A, Parsa A (2020) COVID-19 outbreak highlights: importance of home-based rehabilitation in orthopedic surgery. Arch Bone Jt Surg 8:317–318. https://doi.org/10.22038/abjs.2020.47777.2350

Barnes CL, Zhang X, Stronach BM, Haas DA (2021) The initial impact of COVID-19 on total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 36:56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.01.010

Carassava A (2020) Greeks rein in rebellious streak as draconian measures earn them a reprieve. In: The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/greeks-rein-in-rebellious-streak-as-draconian-measures-earn-them-a-reprieve-tznc0bn6s. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Catellani F, Coscione A, D’Ambrosi R, Usai L, Roscitano C, Fiorentino G (2020) Treatment of proximal femoral fragility fractures in patients with COVID-19 during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Northern Italy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:58. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.20.00617

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M (2020) WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed 91:157–160. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

Ding BTK, Tan KG, Oh JY, Lee KT (2020) Orthopaedic surgery after COVID-19—a blueprint for resuming elective surgery after a pandemic. Int J Surg 80:162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.07.012

Gómez-Barrena E, Rubio-Saez I, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Hernandez-Esteban P (2021) Both younger and elderly patients in pain are willing to undergo knee replacement despite the COVID-19 pandemic: a study on surgical waiting lists. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06611-x

Greek Government (2020). COVID-9-Greece. In: Daily report. https://covid19.gov.gr/covid19-live-analytics. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Hollander JE, Carr BG (2020) Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N Engl J Med 382:1679–1681. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2003539

Kefalas A (2020) L’infectiologue Sotirios Tsiodras, nouvelle coqueluche des Grecs. In: Le figaro. https://www.lefigaro.fr/international/l-infectiologue-sotirios-tsiodras-nouvelle-coqueluche-des-grecs-20200320. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Khan H, Williamson M, Trompeter A (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on orthopaedic services and training in the UK. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 31:105–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-020-02748-6

Knebel C, Ertl M, Lenze U, Suren C, Dinkel A, Hirschmann MT, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Pohlig F (2021) COVID-19-related cancellation of elective orthopaedic surgery caused increased pain and psychosocial distress levels. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29:2379–2385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06529-4

Lee LS, Chan PK, Fung WC (2021) Lessons learnt from the impact of COVID-19 on arthroplasty services in Hong Kong: how to prepare for the next pandemic? Arthroplasty 3:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-021-00093-5

Leochico CF (2020) Adoption of telerehabilitation in a developing country before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 63:563–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.06.001

Li D, Yang Z, Kang P, Xie X (2017) Home-based compared with hospital-based rehabilitation program for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 96:440–447. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000621

Liebensteiner MC, Khosravi I, Hirschmann MT, Heuberer PR, Board of the AGA-Society of Arthroscopy and Joint-Surgery, Thaler M (2020) Massive cutback in orthopaedic healthcare services due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1705–1711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06032-2

Makhni MC, Riew GJ, Sumathipala MG (2020) Telemedicine in orthopaedic surgery: challenges and opportunities. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:1109–1115. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.20.00452

Massey PA, McClary K, Zhang AS, Savoie FH, Barton RS (2020) Orthopaedic surgical selection and inpatient paradigms during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28:436–450. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00360

Mi B, Chen L, Xiong Y, Xue H, Zhou W, Liu G (2020) Characteristics and early prognosis of COVID-19 infection in fracture patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:750–758. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.20.00390

Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom US, Haldorsen B, Svege IC, Hennig T, Pripp AH, Smith HJ (2019) At a 10-year follow-up, tendon repair is superior to physiotherapy in the treatment of small and medium-sized rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 101:1050–1060. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.01373

Mouton C, Hirschmann MT, Ollivier M, Seil R, Menetrey J (2020) COVID-19 ESSKA guidelines and recommendations for resuming elective surgery. J Exp Orthop 7:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40634-020-00248-4

Peto J, Alwan NA, Godfrey KM, Burgess RA, Hunter DJ, Riboli E, Romer P (2020) Universal weekly testing as the UK COVID-19 lockdown exit strategy. Lancet 395:1420–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30936-3

Ravelo J, Jerving S (2020) COVID-19—a timeline of the coronavirus outbreak. In: Inside development COVID-19. DevEx. https://www.devex.com/news/covid-19-atimeline-of-the-coronavirus-outbreak-96396. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J, Macdonald B, Diana Beltekian D, Roser M (2020) Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). In: Ourworldindata. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

Schatz C, Leidl R, Plötz W, Bredow K, Buschner P (2022) Preoperative patients’ health decrease moderately, while hospital costs increase for hip and knee replacement due to the first COVID-19 lockdown in Germany. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-022-06904-9

Tachakra S, Lynch M, Newson R, Stinson A, Sivakumar A, Hayes J, Bak J (2000) A comparison of telemedicine with face-to-face consultations for trauma management. J Telemed Telecare 6:178–181. https://doi.org/10.1258/1357633001934591

Tanaka M, Oh L, Martin S, Berkson M (2020) Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19: the virtual orthopaedic examination. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102:57. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.20.00609

Thaler M, Khosravi I, Hirschmann MT, Kort NP, Zagra L, Epinette JA, Liebensteiner MC (2020) Disruption of joint arthroplasty services in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey within the European hip society (EHS) and the European knee associates (EKA). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1712–1719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06033-1

Thaler M, Kort N, Zagra L, Hirschmann MT, Khosravi I, Liebensteiner M, Karachalios T, Tandogan RN (2021) Prioritising of hip and knee arthroplasty procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic: the European hip society and the European knee associates survey of members. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29:3159–3163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06379-6

Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A (2020) The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66:317–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK: conceived and design the analysis, wrote the manuscript, ODS: performed the analysis, supervised the project, CB: performed the analysis, PS: acquisition of data, MS: acquisition of data, AT: acquisition of data, EP: supervised the project, interpretation of data, PJP: conceived and design the analysis, review of the manuscript, AE: revision of the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published, SE: revision of the manuscript, final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Yes.

Informed consent

Yes.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalogeropoulos, A., Savvidou, O.D., Bissias, C. et al. Milder impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the practice of orthopaedic surgery in Greece and Cyprus than other European countries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31, 110–120 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-022-07159-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-022-07159-0