Abstract

Purpose

The aims of this study are to evaluate whether improvements in functional outcome and quality of life are sustainable 10 years after total knee arthroplasty (TKA), and the age cut-off for clinical deterioration in outcomes

Methods

Prospectively collected registry data of 120 consecutive patients who underwent TKA at a tertiary hospital in 2006 was analysed. All patients were assessed at 6 months, 2 years and 10 years using the Knee Society Function Score, Knee Society Knee Score, Oxford Knee Score, Short-Form 36 Physical/Mental Component Scores and postoperative satisfaction. One-way ANOVA was used to compare continuous variables, while Chi-squared test to compare categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression and receiver operating curve analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive factors associated with deterioration of scores postoperatively.

Results

Significant improvements were noted in all functional outcome and quality of life scores at 6 months after TKA. Between 6 months and 2 years, the KSFS and OKS continued to improve but the KSKS, PCS and MCS plateaued. Between 2 and 10 years, there was a deterioration in the KSFS and OKS, whilst KSKS, PCS and MCS were maintained. Increasing age was noted to be a significant risk factor for deterioration of KSFS at 10 years with age ≥ 68 as the cut-off value. 91.7% of patients with KSFS Minimally Clinically Important Difference(MCID) (≥ 7 points) continued to be satisfied after 10 years compared to 100.0% who did not experience KSFS MCID deterioration (p = 0.02).

Conclusion

Patients ≥ 68 years experience deterioration in functional outcomes and quality of life from 2 to 10 years after TKA.

Level of evidence

Retrospective study, Level III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

TKA has been proven to be an effective surgical treatment for end stage osteoarthritis with substantial improvements in functional outcome and quality of life [20]. However, with an increasingly ageing population that is staying active after retirement, there is a paradigm shift in patients’ long term expectations after TKA [23]. Both surgeons and patients are interested to know if early improvements in functional outcome and quality of life after TKA can be maintained up till 10 years after the surgery.

There have been many studies conducted that evaluated outcomes following TKA based on various measures or scores, and many of which have analysed these outcomes from the preoperative periods up to 2 years follow up [4, 11, 17, 19, 29, 31]. From these, the authors are confident to say that outcome measures do significantly improve for patients who underwent TKA and are sustainable up till 2 years. However, there is a lack of studies with longer follow up periods with regular follow up intervals, resulting in insufficient data showing whether functional improvement after TKA can last up to 10 years [14, 15].

Hence, the objectives of this study are to evaluate if there is a significant deterioration in functional outcome and quality of life scores between 2 and 10 years after TKA, and to determine the age cut-off for patients who experience deterioration in clinical outcomes and quality of life from 2 to 10 years follow-up. The authors hypothesize that functional outcomes and quality of life post TKA would deteriorate over a 10 year follow up.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the authors’ hospital’s ethics board (CIRB: 2018/2150) and performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

For this study, 302 patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis and underwent primary unilateral TKA in 2006 at a tertiary hospital were included in this study. Among these patients, four had rheumatoid arthritis, 41 had contralateral knee osteoarthritis, 39 patients passed away due to unrelated issues, and 98 had incomplete data or were lost to follow up. These patients were excluded. The final number included in our study was 120 patients. The average age of patients that underwent total knee arthroplasties was 65 years old and the average BMI was 27.9 kg/m2. Patients’ demographics are stated in Table 1. The authors also evaluated the demographics of the 98 patients with incomplete data or lost to follow up, and found comparable mean age, gender proportion and average BMI with the study sample without any statistically significant difference.

All surgeries were by two fellowship-trained adult reconstruction surgeons (SJY and NNL), using the medial parapatellar approach with patella eversion. A tourniquet was used and no drain was placed intraoperatively. All patients received cemented, fixed bearing TKA implants. They underwent a standardized postoperative TKA physiotherapy protocol at our hospital.

These patients were assessed preoperatively, at 6 months, 2 years and 10 years after TKA by an independent healthcare professional. Functional outcomes were quantified using the Knee Society Score [12] and the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) [21]. The Knee Society Score is a 200-point scoring system [12], which comprises the Knee Society Function Score (KSFS) and the Knee Society Knee Score (KSKS). KSFS is out of 100 points, and assesses pain, alignment, ROM and stability. KSKS, also out of 100 points, assesses the patient’s general functionality [26]. As data collection began in 2006 before the OKS was modified [21], the original OKS was used, as described by Dawson et al. [6], which consists of 12 questions (5 for assessing pain and 7 for assessing function) that sums to a give a score ranging from 12 to 60, with 12 being the best outcome. For the outcome on general quality of life, it was evaluated using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire [13]. Our authors transformed the eight domains of the SF-36 questionnaire (physical functioning, social functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, mental health, role-emotional, vitality and general health) into two summary scores: the Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS). This was to allow a smaller confidence interval and the elimination of both floor and ceiling effects [27].

Sample size calculation was done based on the minimal clinically importance difference (MCID) of KSFS. To detect a seven points difference with a standard deviation of 20, a sample size of at least 109 patients was required to achieve a power of 0.95. This calculation was done for a 2-sided test with a type I error of 0.05.

In this study, our authors defined clinically significant difference using the known MCID thresholds of each score from the existing literature: KSFS (7 points) [18], KSKS (6 points) [18], OKS (5 points) [5], PCS (10 points) [25] and MCS (10 points) [25]. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive factors associated with a deterioration of ≥ 7 points in KSFS between 2 and 10 years after TKA. Additional analysis was then performed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, with age as the predictor and deterioration of ≥ 7 points in KSFS as the criterion. The optimal Youden’s index on the ROC curve was used to determine the cut-off value for age.

Patients’ overall satisfaction and expectation fulfilment with regards to their surgeries were also measured. Patients graded their overall satisfaction level at the 10-year follow up as either “terrible”, “poor”, “fair”, “good”, “very good” or “excellent”. These were further dichotomized these into groups – the “dissatisfied” and “satisfied” groups. Those patients who graded their satisfaction level as “terrible”, “poor” or “fair” were put under the “dissatisfied” group, while those who graded “good”, “very good” or “excellent” were classified under “satisfied”. Regarding expectation fulfilment, patients graded the extent their expectations were met as “No, not at all”, “No, far from it”, “No, not quite”, “More or less”, “Yes, quite a bit”, “Yes, almost totally” or “Yes, totally”. These results were then furthered dichotomized into two groups—the “expectations unfulfilled” and “expectations fulfilled” groups. The “expectations unfulfilled” group comprised patients who responded “No, not at all”, “No, far from it”, “No, not quite” or “More or less”. The “expectations fulfilled” group comprised patients who responded with “Yes, quite a bit”, “Yes, almost totally” or “Yes, totally”. Following this, the 120 patients were grouped into those who had deterioration of ≥ 7 points and those who had a deterioration of < 7 points in KSFS between 2 and 10 years after TKA. Between the two groups, the proportions of satisfied patients, as well as patients with fulfilled outcome and quality of life scores at different timelines were compared, while the chi-squared analysis was used to compare categorical data. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p value ≤ 0.05.

Results

A total of 120 patients were included in this study. None of the 120 patients had revision surgery or knee manipulation under anaesthesia during the 10 year follow-up period. Radiographs of all 120 patients at the 10-year follow-up mark did not show any evidence of implant loosening.

Table 2 showed the functional outcome and quality of life scores of the patients at their preoperative and follow-up visits. There were significant improvements in all functional outcome and quality of life scores at 6 months after TKA (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Between 6 months and 2 years, the KSFS and OKS continued to improve but there was a plateau with the KSKS, PCS and MCS. Between 2 and 10 years, there were deteriorations noted in the KSFS and OKS. There were otherwise no significant changes in the KSKS, PCS and MCS (Table 3). The study also noted that there was a deterioration of 8 (95% CI 3, 13) points in KSFS from 2 to 10 years. This was more than the known MCID threshold of 7 points and hence was considered to be clinically relevant.

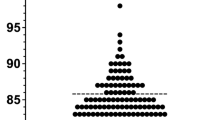

Further analysis was done and identified that increasing age (OR 1.128 per unit increase, 95% CI 1.055, 1.206, p < 0.001) was a significant predictor for deterioration of ≥ 7 points in KSFS between 2 and 10 years after TKA. The ROC curve was constructed and analysed (Fig. 1), revealing an area under curve of 0.738 (95% CI 0.649, 0.827), which further indicated increasing age as a sensitive predictive value for the deterioration of KSFS. With the optimal Youden’s index on the ROC curve, age ≥ 68 as the cut-off value had a 55.9% sensitivity, 80.3% specificity, 73.3% positive predictive value and a 65.3% negative predictive value for predicting a deterioration of ≥ 7 points in KSFS between 2 and 10 years after TKA. Preoperative scores, gender and BMI were not significant predictors for deterioration in the KFSF score at 10 years after TKA (all p > 0.05).

In terms of satisfaction levels, a significantly lower proportion of patients with MCID deterioration ≥ 7 was satisfied compared to those with MCID deterioration < 7 (p < 0.05). In terms of expectations fulfilled, a significantly lower proportion of patients with MCID deterioration ≥ 7 had their expectations fulfilled compared to those with MCID deterioration < 7 (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

The most important findings of the present study were: (1) an 8-point deterioration of KSFS from 2 to 10 years post TKA, which was higher than the MCID threshold of 7 points; (2) increasing age ≥ 68 years was a significant predictor of deteriorating MCID scores ≥ 7 points; (3) a lower proportion of patients with MCID scores deterioration ≥ 7 were satisfied and had their expectations fulfilled compared to those with MCID scores deterioration < 7.

With advances in medical technology and an increasing ageing population, especially where some still remain active after retirement, it is important to identify if a TKA remains compatible with their level of activity and satisfaction years after the operation [15]. As mentioned, there are many studies at present that evaluated both functional and quality of life outcome post-TKA at follow-up periods up to 2–5 years [3, 8, 11, 16, 17, 19, 28, 29]. In line with previous studies done, significant improvements in both the functional and the satisfactory outcome scores were noted at 6 months post-TKA from this study. The KSFS and OKS continued to show further improvements at 2 years follow up while the other assessment scores were maintained, hence showing that functional outcome after TKA is sustainable after 2 years. This also concurs with the current evidence available in the literature regarding post-TKA outcomes.

At the 10-year follow-up period, deterioration was noted in both the KSFS and OKS whilst the other outcome scores remained. A comparison between this study and the available literature on 10-year follow-up post-TKA is presented (Table 5). Based on Kennedy et al. [15], a study which compared the KSKS and KSFS between two groups (octogenarians > 80 years and younger group < 80 years) at 3, 5 and 10 years, they found deterioration of the KSFS in both groups between 3 and 10 years but noted the KSFS score being lower in the octogenarian group than the other. Goh et al. [10] also reported octogenarians to have significantly lower KSFS scores compared to their younger counterparts post-TKA at the 2-year follow-up visit. Similarly, this study also noted a decrease in the KSFS at 10 years and our further analysis revealed that increasing age, especially for patients aged ≥ 68 years, was a significant risk factor for this deterioration.

In this study, both KSFS and OKS scores deteriorated at 10-year follow-up but not the KSKS score, which was maintained at 10 years post-TKA. The authors attribute this finding to the collation of different information in between the scores. KSKS focuses on range of motion, alignment and pain. These are aspects that are unlikely to be affected by patient comorbidities such as cardiac diseases, pulmonary diseases, peripheral arterial disease, kidney diseases etc. [15]. However for KSFS and OKS, they encompass information of general functionality like ambulatory distance, use of aids and daily activities that can be affected by factors which are more prevalent in the elderly population [7, 15].

Jiang et al. [14] conducted a study in the United Kingdom (UK) that aimed to identify preoperative predictive factors for pain and functional outcomes (primary outcome measure was the OKS) 10 years after a TKA. They found that patients > 80 years of age achieved a poorer outcome score (OKS) and increasing age was a risk factor. Furthermore, they also noted another age-related predictor outcome, where patients < 60 years of age experienced a poorer outcome score after 10 years post-TKA. This finding was also present in the study by Williams et al. [28]. However, this age pattern distribution of poorer outcome scores in younger patients was not noted in this study. In contrast to Jiang et al., Goh et al. [11] explored TKA outcomes in those of younger age groups and have found that patients < 50 years of age who underwent a TKA could achieve good to excellent knee function scores, where 94.9% of the patients met the MCID for OKS at the 2 years postoperative review. However, it must be taken into consideration that the results were recorded at 2 years postoperatively, as compared to a 10-year follow-up study.

In addition, Jiang et al. [14] and Williams et al. [28] also found that patients with poor preoperative scores and those with BMI > 35 were associated with worse clinical outcomes. This finding was also noted by Xu et al. [30], who noted patients with BMI > 30 who underwent TKA had significantly lower OKS and MCS scores at the 10-year follow-up visit. However, this study did not show that BMI and preoperative scores were significant predictors for poorer outcomes. In terms of gender differences, there were no significant difference between genders influencing post-TKA future outcomes despite a 5:1 female to male distribution ratio. In contrast, Jiang et al. [14] compared future scores between genders and have found that the female gender experiences poorer outcomes compared to males as opposed to this study.

With regards to the quality of life scores, Xie et al. [29] conducted a 2 year quality of life outcome analysis of patients after undergoing TKA. They reported improvement in the PCS up to 2-year follow-up but noted that the overall MCS remained stagnant at 6 months and 2 years postoperatively. However, the role emotional component of the MCS showed significant improvement. This might possibly relate to positive emotions or attitudes towards the TKA, which might have contributed to the improvement of the PCS score, hence suggesting that the components of the PCS and MCS score may be directly proportional to one another. Similar outcomes noted in our study included improvement in PCS at 6 months, but also in addition, significant improvement in MCS at 6 months. The PCS and MCS scores remained stagnant till 2 years concurring with outcomes from Xie et al. and the scores were maintained up to 10 years. Hence, this reflects that the early improvements in quality of life outcomes are sustainable through 10 years postoperatively. With the findings from this study, better counselling can be given to patients about the general outcomes of TKAs and its predictive outcome factors during preoperative consultation.

Regarding satisfaction rates and expectation fulfilment after 10 years post TKA, this study noted differences between patients with MCID deterioration ≥ 7 and < 7 in KSFS (from 2 to 10 years follow-up). Even though the differences in satisfaction rate and expectations fulfilled between both groups were significant (p < 0.05), it is interesting to note that 91.7% of those with MCID deterioration ≥ 7 still remained satisfied. The 91.7% satisfaction rate in the group with MCID deterioration ≥ 7 is higher than the reported post TKA satisfaction rate in the literature. The reported satisfaction rate is between 81 and 90% [1, 22], but this mainly involves satisfaction rates up to 5-year follow-up. The authors attribute the higher rates to the high proportion of patients with expectation fulfilled (90%).

The strength of this study is the availability of long-term data, which allowed the authors to evaluate the outcomes of patients who underwent unilateral TKA after 10 years. From this study, proper counselling regarding the long term sustainability of improvements in functional outcomes and quality of life is recommended for patients ≥ 68 years undergoing TKA. However, there are limitations to this study. Firstly, the study was retrospective in nature. Future prospective studies will be needed to further validate our findings. Secondly, patients included are from a single hospital hence there may be inherent selection bias. Thirdly, there were a group of patients who were lost to follow up in the 10 year study. Nevertheless, analysis showed that the demographics of the group lost to follow up were comparable to the final study group of 120 patients. Lastly, this study had a relatively small sample size of 120 patients. Despite this small sample size, this study is adequately powered.

Conclusion

This study found a clinically significant deterioration in KSFS between 2 and 10 years after TKA, with increasing age as an important risk factor. Patients ≥ 68 years experience deterioration in functional outcomes and quality of life from 2 to 10 years after TKA.

References

Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD (2010) Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res 468:57–63

Bourne RB, McCalden RW, MacDonald SJ, Mokete L, Guerin J (2007) Influence of patient factors on TKA outcomes at 5 to 11 years followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res 464:27–31

Chen JY, Lo NN, Chong HC, Razak HRBA, Pang HN, Tay DKJ et al (2016) The influence of body mass index on functional outcome and quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am 98-B:780–785

Chen JY, Lo NN, Chong HC, Pang HN, Tay DK, Chin PL et al (2015) Cruciate retaining versus posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty after previous high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:3607–3613

Clement ND, MacDonald D, Simpson AH (2014) The minimal clinically important difference in the Oxford knee score and Short Form 12 score after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22:1933–1939

Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A (1998) Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Am 80-B:63–69

Dowsey MM, Choong PF (2013) The utility of outcome measures in total knee replacement surgery. Int J Rheumatol 2013:1–8

Giesinger JM, Hamilton DF, Jost B, Behrend H, Giesinger K (2015) WOMAC, EQ-5D and Knee society score thresholds for treatment success after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 30:2154–2158

Gill GS, Joshi AB (2001) Long-term results of kinematic condylar knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Am 83-B:355–358

Goh GS, Liow MHL, Chen JY, Tay DK, Lo NN, Yeo SJ (2020) Can octogenarians undergoing total knee arthroplasty experience similar functional outcomes, quality of life, and satisfaction rates as their younger counterparts? A propensity score matched analysis of 1188 patients. J Arthroplasty 35:1833–1839

Goh GS, Liow MHL, Bin Abd Razak HR, Tay DK, Lo NN, Yeo SJ (2017) Patient-reported outcomes, quality of life, and satisfaction rates in young patients aged 50 years or younger after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 32:419–425

Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN (1989) Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 248:13–14

Ware JE, Sherbo CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Jiang Y, Sanchez-Santos MT, Judge AD, Murray DW, Arden NK (2017) Predictors of patient-reported pain and functional outcomes over 10 years after primary total knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study. J Arthroplasty 32(92–100):e102

Kennedy JW, Johnston L, Cochrane L, Boscainos PJ (2013) Total knee arthroplasty in the elderly: does age affect pain, function or complications? Clin Orthop Relat Res 471:1964–1969

Ko Y, Lo NN, Yeo SJ, Yang KY, Yeo W, Chong HC et al (2013) Comparison of the responsiveness of the SF-36, the Oxford Knee Score, and the Knee Society Clinical Rating System in patients undergoing total knee replacement. Qual Life Res 22:2455–2459

Lee J, Kim J-h, Jung E-J, Lee B-h (2017) The comparison of clinical features and quality of life after total knee replacement. J Phys Ther Sci 29:974–977

Lee WC, Kwan YH, Chong HC, Yeo SJ (2017) The minimal clinically important difference for Knee Society Clinical Rating System after total knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:3354–3359

Lim JB, Chou AC, Yeo W, Lo NN, Chia SL, Chin PL et al (2015) Comparison of patient quality of life scores and satisfaction after common orthopedic surgical interventions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 25:1007–1012

Martin GM, Harris I (2020) Total knee arthroplasty. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/total-knee-arthroplasty?search=totalkneereplacement&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~115&usage_type=default&display_rank=1. Accessed 29 Apr 2020

Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, Pandit H, Beard DJ, Carr AJ et al (2007) The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Jt Surg Am 89:1010–1014

Nam D, Nunley RM, Barrack RL (2014) Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Am 96B:96–100

Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM (2009) Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop 80:55–61

Rat AC, Guillemin F, Osnowycz G, Delagoutte JP, Cuny C, Mainard D et al (2010) Total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis: mid- and long-term quality of life. Arthritis Care Res 62:54–62

Razak HRBA, Tan CS, Chen YJD, Pang HN, Darren Tay KJ, Chin PL, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ (2016) Age and preoperative knee society score are significant predictors of outcomes among asians following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am 98:735–741

Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, Benjamin JB, Lonner JH, Scott WN (2012) The new Knee Society Knee Scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470:3–19

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Mchorney CA, Ware JE, Kosinski M et al (1995) Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical ana of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary results from the medical outcome. Med Care 33:AS264–AS279

Williams DP, Blakey CM, Hadfield SG, Murray DW, Price AJ, Field RE (2013) Long-term trends in the Oxford knee score following total knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Am 95 B:45–51

Xie F, Lo NN, Pullenayegum EM, Tarride JE, O'Reilly DJ, Goeree R et al (2010) Evaluation of health outcomes in osteoarthritis patients after total knee replacement: a two-year follow-up. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8:1–6

Xu S, Chen JY, Lo NN, Chia SL, Tay DKJ, Pang HN et al (2018) The influence of obesity on functional outcome and quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am 100B:579–583

Zhou Z, Yew KS, Arul E, Chin PL, Tay KJ, Lo NN et al (2015) Recovery in knee range of motion reaches a plateau by 12 months after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:1729–1733

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NCSS Award (13/FY2017/P1/16-A30).

Funding

Nil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were fully involved in the study and preparation of the manuscript and the material within has not been and will not be submitted for publication elsewhere.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the hospital’s ethics board (CIRB: 2018/2150) and performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, B.J., Chen, J.Y., Lai, Y.M. et al. Improvements in functional outcome and quality of life are not sustainable for patients ≥ 68 years old 10 years after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29, 3330–3336 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06200-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-020-06200-4