Abstract

Purpose

No comparative studies of outcomes between degenerative medial meniscus posterior root tear (MM PRT) and non-root tear (NRT) have been conducted. This study aimed to compare joint survival and clinical outcome between MM PRT and MM NRT after partial meniscectomy with proper control of confounding factors.

Methods

One hundred and ten patients each in MM PRT and MM NRT groups who underwent arthroscopic partial meniscectomy were retrospectively evaluated through propensity score matching. Joint survival was assessed on the basis of surgical and radiographic failures. Clinical outcomes were assessed using the Lysholm score.

Results

The confounding variables were well balanced between the groups, with standardized mean differences of < 0.2 after propensity score matching. Failures occurred in 30 (27.3%) and 35 patients (31.8%) in the MM PRT group and MM NRT group, respectively. The estimated mean survival times were 12.5 years (95% confidence interval [CI] 11.5–13.5) and 11.7 years (10.7–12.7), respectively. There were no significant differences in the overall survival rate and Lysholm score between the two groups (n.s.).

Conclusion

In middle-aged patients with degenerative MM PRT, joint survival and clinical outcome showed comparable results with those with MM NRT after partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is one of the effective treatments for MM PRT with consideration of various patient factors.

Level of evidence

III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Middle-aged patients with degenerative medial meniscus (MM) tear often experience mechanical symptoms such as painful clicking, catching, pain on squatting, and giving way. These symptoms make it difficult for affected persons to perform daily activities, which leads to a low quality of life. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) is an effective surgical treatment for patients with symptomatic meniscal tears who do not respond to conservative management [8, 19, 27, 38]. APM has some benefits for relieving symptoms and helping patients return to daily activities [13, 15, 28]. However, the meniscus is an important structure for axial load distribution and shock absorption in the knee joint [18]. Therefore, although removal of the meniscal fragment in case of a symptomatic tear can improve clinical symptoms, the surgeon should consider that meniscectomy can lead to arthritic changes such as joint space narrowing, formation of osteophytes, and femoral and tibial bony changes [20, 44, 46].

MM posterior root tear (MM PRT) in itself is considered similar to the state of total meniscectomy. A complete detachment of the posterior root causes disruption of circumferential meniscal fibers. Thus, the MM cannot provide the hoop stress mechanism, which is an important function for distributing axial loads. Thereby, MM PRT can cause meniscal extrusion and contribute to the rapid progression of arthritic change [1, 31, 32, 42]. A biomechanical study also showed that MM PRT resulted in increasing peak contact pressure in the knee joint as compared with the intact knee, and no significant difference in peak contact pressure was observed between MM PRT and the state of total medial meniscectomy [3]. Although acute medial meniscus root tear in young patients should be repaired for restoration of knee biomechanics, most MM PRTs observed in middle-aged patients were degenerative tears in clinical practice and had preexisting medial knee osteoarthritis [24, 29, 40, 41, 45]. Therefore, the best degenerative MM PRT treatment is still controversial. Some studies reported poor clinical results regardless of the treatment (partial meniscectomy or conservative treatment) for MM PRT [11, 35, 36, 48].

For these reasons, MM PRT was generally considered to have a worse prognosis than MM non-root tear (MM NRT). As mentioned earlier, MM PRT clearly affected the progression of osteoarthritis and disruption of joint biomechanics. Even though mechanical symptoms could be improved after partial meniscectomy in both MM PRT and MM NRT during a short postoperative period, we thought that APM for degenerative MM PRT would have worse clinical courses of joint survival and clinical outcomes than those for degenerative MM NRT. However, the lack of proper control of confounding factors made comparison of the outcomes after APM between MM PRT and MM NRT more difficult. If various confounding factors are properly controlled, determining the effect of tear morphology on long-term outcomes in case of degenerative MM tears after partial meniscectomy, especially by comparing MM PRT and MM NRT, would be helpful. To our knowledge, no previous comparative studies of the effect of partial meniscectomy on long-term joint survival according to the type of degenerative MM tear have been conducted.

The purpose of this study was to compare the joint survival and clinical outcome between degenerative MM PRT and MM NRT with partial meniscectomy after the proper control of confounding factors. It was hypothesized that degenerative MM PRT would show worse results than degenerative MM NRT in terms of joint survival and clinical outcome after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy.

Materials and methods

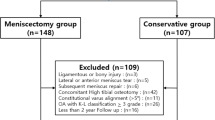

Patients who underwent APM for degenerative MM tears between January 1999 and July 2012 were retrospectively evaluated using prospectively collected data. Patients with degenerative MM tear identified on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging, and persistent or aggravating mechanical symptoms for at least 3 months despite conservative treatment (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle strengthening exercise) were indicated for partial meniscectomy. The contraindications for partial meniscectomy were evidence of varus thrust gait on physical examination, advanced medial osteoarthritis such as joint space obliteration or Kellgren–Lawrence grade 4 osteoarthritic change on standing radiography, and diffuse full-thickness cartilage wear of the medial compartment on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (1) age of > 40 years, (2) follow-up period of > 4 years, and (3) sole operation for degenerative MM tear. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) history of prior knee surgery (meniscus, cartilage, or ligament operation) on the affected knee; (2) traumatic tear of the medial meniscus with a recent history of knee trauma; (3) complex tear accompanied by both posterior root tear and non-root tear; (4) concurrent lateral meniscus tear; and (5) additional operative procedures such as chondroplasty, microfracture, and osteochondral autograft transplantation. A total of 453 patients who met the criteria were finally included in the study.

The 453 patients were divided into two groups according to the type of meniscus tear, which was confirmed with arthroscopic examination. The arthroscopic findings were recorded in a preformatted electronic document system [39]. Those with degenerative MM PRT with detached posterior root or a complete radial tear within 9 mm from the posterior bony root attachment were defined as the “MM PRT group” [37]. Those with other types of degenerative MM tear with intact posterior root attachment, such as a longitudinal-vertical, horizontal, radial, vertical flap, horizontal flap, or complex tear pattern, according to the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine classification of meniscal tears, were defined as the “MM NRT group” [4]. Thus, 288 patients were divided into the MM PRT group; and 165, into the MM NRT group.

To control for potential confounding variables, we matched the patients from the MM PRT and MM NRT groups through propensity score matching. This statistical method allowed us to perform a retrospective study with minimizing the interferences of covariates that mimicked the characteristics of randomized controlled trials [7]. We calculated propensity scores using logistic regression analysis and considered the following variables: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), anatomical axis on a standing anteroposterior (AP) radiograph, cartilage status of the medial compartment (Outerbridge grade of the medial femoral condyle and medial tibia plateau), and follow-up period. Each patient in the MM PRT group was matched to a patient in the MM NRT group by matching the closest propensity score at a 1:1 ratio. Thus, 110 patients in each group were included in the study.

Although the mechanical axis measured on whole-leg standing radiographs reflected the accurate alignment of the knee, not all the patients underwent whole-leg standing radiography before surgery. Therefore, we measured the anatomical axis of the knee on 14 × 17-in AP standing radiographs as covariate for alignment [49]. The digital caliper tool available in the Picture Archiving and Communication System was used to measure the axis. The tool could measure the angle with a precision of 1°. The evaluation of the medial compartmental cartilage (medial femoral condyle and medial tibia plateau) was confirmed using the Outerbridge grading system by a single senior surgeon during arthroscopic examination. Postoperative radiographs and clinical scores were determined annually. Joint survival after partial medial meniscectomy was assessed on the basis of surgical and radiographic failures. Surgical failures were defined as any requirement for reoperations, including arthroscopic revision surgery for the MM (subtotal or total meniscectomy), realignment osteotomy, and total knee arthroplasty. Radiographic failure was defined as developing Kellgren–Lawrence grade 4 osteoarthritis on follow-up standing AP radiographs. The Kellgren–Lawrence grade was assessed by two senior orthopedic surgeons through a discussion. The clinical outcome was assessed and compared using Lysholm scores preoperatively and at the latest postoperative follow-up. The intra-observer and inter-observer reliability for measurements were analyzed. The intra-class correlation coefficient was 0.930, and the inter-observer correlation coefficient was 0.875 for the measurement of anatomical axis. The kappa value of the intra-observer agreement was 0.834, and that of the inter-observer agreement was 0.808 for the Kellgren–Lawrence grade. Therefore, the measurements by one rater were used for the statistical analyses.

All operations were performed by a single senior orthopedic surgeon. The goal of the operation for a meniscus tear was to sufficiently remove the torn meniscal fragment to resolve mechanical symptoms. Moreover, we attempted to leave an intact meniscus tissue as much as possible. Remnant meniscal tissue was trimmed to a semilunar shape. The remaining meniscal width was measured using a probe, and the resection left a meniscal width of > 3 mm with an intact peripheral rim was defined as partial meniscectomy. The remnant meniscus was evaluated by probing for a possible impingement that could cause mechanical symptoms. The patients were allowed to perform full range of motion and quadriceps setting exercises immediately after surgery. Early weight-bearing ambulation was allowed as necessary, and gradual muscle strengthening exercise was encouraged as soon as possible. This retrospective study was approved by our internal institutional review board (Asan Medical Center, project No. 2018-1179).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 18.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R version 2.8.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables (age, BMI, anatomical axis, and follow-up period) were analyzed using the Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables (gender and medial cartilage state) were analyzed using the Pearson Chi-square test. Propensity scores were calculated using a logistic regression analysis of the covariates (age, gender, BMI, anatomical axis on standing AP radiographs, cartilage state of the medial femoral condyle and medial tibial plateau, and follow-up period). Each patient in the MM PRT and MM NRT groups was matched depending on the nearest propensity score at a 1:1 ratio without replacement (greedy algorithm). The caliper was set to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. Model classification ability was assessed using c-statistics (c = 0.509), and model calibration ability was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (p = 0.193). To evaluate the balance before and after matching, we calculated the standardized mean difference for each covariate [5, 6]. Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to assess joint survival and compare the overall survival rate. A subgroup analysis of joint survival according to preoperative anatomical alignment and preoperative Kellgren–Lawrence grade (grade 0 or 1 vs grade 2 or 3) was performed. The preoperative anatomical alignment was classified as neutral (2°–10° valgus) or varus (< 2° valgus) [47]. The Student t test was used for comparing the modified Lysholm score. Post-hoc analysis of the Student t test results was performed to determine the statistical power using the G-power version 3.1.5 software. A Cohen medium effect size of 0.5, an alpha level of 0.05, and a sample size of 110 in an unpaired two-tailed t test suggested a power (1-beta) level of 0.958.

Results

Table 1 shows the patients’ characteristics in the total and propensity-matched cases. All variables were well balanced, with a standardized mean difference of < 0.2. After matching, failures were found in 30 patients (27.3%) in the MM PRT group and in 35 patients (31.8%) in the MM NRT group. MM PRT group showed 20 cases of TKA conversion, 1 case of arthroscopic MM revision meniscectomy, and 9 cases of Kellgren-Lawrence grade 4 osteoarthritis at follow-up. The MM NRT group showed 24 cases of TKA conversion, 1 case of arthroscopic MM revision meniscectomy, and 10 cases of Kellgren–Lawrence grade 4 osteoarthritis at follow-up. The joint survival rate in the MM PRT group was 92.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 86.0–96.3%) at 5 years and 76.3% (95% CI 64.6–84.6%) at 10 years. The joint survival rate in the MM NRT group was 87.2% (95% CI 79.4–92.2%) at 5 years and 78.4% (95% CI 67.9–85.9%) at 10 years. The 5- and 10-year joint survival rates between the two groups were not significantly different (n.s.). The estimated mean survival time was 12.5 years (95% CI 11.5–13.5%) in the MM PRT group and 11.7 years (95% CI 10.7–12.7%) in the MM NRT group. The overall survival rates in the MM PRT and MM NRT groups were analyzed using the log-rank test, and no significant difference was found between the two groups (n.s.; Fig. 1).

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the joint survival of patients after partial meniscectomy between subgroups of medial meniscus (MM) tear. Terminal events were defined as cases that required any reoperation (including arthroscopic revision surgery for MM, realignment osteotomy, and total knee arthroplasty) and Kellgren–Lawrence grade 4 osteoarthritis on the follow-up radiograph

Subgroup analyses of joint survival according to anatomical alignment and Kellgren–Lawrence grade were performed (Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3). The 5- and 10-year joint survival rates and overall survival rate between the two groups were not significantly different (n.s.)

The clinical outcomes are shown in Table 3. The mean modified Lysholm score was improved from 63.5 ± 16.7 preoperatively to 83.7 ± 14.5 at the last follow-up in the MM PRT group (p < 0.001) and from 64.8 ± 13.4 preoperatively to 84.9 ± 14.2 at the last follow-up in the MM NRT group (p < 0.001). No significant differences in the preoperative and postoperative modified Lysholm scores and changes in the score were found between the two groups.

Figures 4 and 5 are examples of standing AP radiographs of the MM PRT and MM NRT patients, showing similar clinical courses.

Preoperative and latest standing anteroposterior radiographs of the left knee. a Preoperative radiograph of a 58-year-old woman with medial meniscus posterior root tear and the latest radiograph taken 12.2 years after surgery. b Preoperative radiograph of a 53-year-old woman with medial meniscus non-root tear (degenerative horizontal tear) and latest radiograph taken 13 years after surgery. Both patients showed improved mechanical symptoms of meniscus tear after partial medial meniscectomy, with little arthritic change over a long-term follow-up period

Preoperative and follow-up standing anteroposterior radiographs of the left knee. a Preoperative radiograph of a 58-year-old woman with medial meniscus posterior root tear and the follow-up radiograph taken 2.2 years after surgery. b Preoperative radiograph of a 50-year-old woman with medial meniscus non-root tear (degenerative flap and horizontal tear) and the follow-up radiograph taken 2.8 years after surgery. Both patients complained of arthritic pain after partial medial meniscectomy over a short-term follow-up period and underwent total knee arthroplasty

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that APM for degenerative MM PRT shows comparable results in terms of joint survival and clinical outcome with APM for MM NRT. To our knowledge, this is the first comparative study about joint survival and clinical outcome after partial meniscectomy between tears of the MM posterior root and MM itself (with intact posterior root). Both groups showed a similar frequency of failures, estimated mean survival time, and overall survival rate. The subgroup analysis according to alignment and joint degeneration also showed comparable results. Moreover, the patient’s mechanical symptoms improved, and no significant differences in clinical outcome were found over a long follow-up period. Therefore, degenerative MM PRT does not show worse results than degenerative MM NRT in terms of joint survival and clinical outcome after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After matching confounding factors, it is difficult to conclude that the type of medial meniscus tear determines joint survival after partial meniscectomy.

The treatment of degenerative MM PRT in middle-aged patients remains controversial. Theoretically, the repair of the posterior root attachment may restore the joint hoop stress and decrease the peak contact pressure on the tibiofemoral joint [3]. Several clinical studies reported favorable clinical outcomes of MM PRT repair [23, 34, 41]. Furthermore, recent studies showed that repair of medial meniscus root tears with pre-existing intact cartilage and well-aligned knee leads to less progression of osteoarthritis [21, 30]. Therefore, refixation was the generally recommended treatment for medial meniscus root tear. Although surgery provides benefits for an isolated meniscal root tear with early knee osteoarthritis, meniscal root repair should be considered carefully on the basis of the strict surgical indications, especially considering age, alignment, and cartilage status [2, 16]. The strict surgical criteria for root repair are often not applicable to patients that orthopedic surgeons attend to in clinics. Furthermore, meniscal root repair does not always show good results and often show poor healing rate, increased meniscal extrusion, and progression of the medial compartment cartilage defect in the short follow-up period [33]. APM may be considered as a treatment option with a simple technique and short operative and recovery times and as a palliative treatment for some middle-aged patients with mild varus alignment and mild arthritic change who do not meet the surgical indications for root repair [11, 38]. Therefore, both treatment methods of partial meniscectomy and meniscal root repair must be undertaken carefully according to individual characteristics. In our study, we aimed to analyze the effect of tear morphology on the long-term outcome of knees and to determine whether significant differences in joint survival and outcome could be found between MM PRT and MM NRT after partial meniscectomy in middle-aged patients with degenerative MM tears who underwent the partial meniscectomy.

APM was generally performed to relieve the mechanical symptoms of meniscal tears [9, 17]. However, APM cannot restore the biomechanical function of the knee. Moreover, several studies reported poor clinical results after APM for MM PRT. Krych et al. analyzed the efficacy of partial meniscectomy in comparison with the non-operative treatment of MM PRT [36]. They reported no significant difference in clinical outcomes and overall failure rates between the partial meniscectomy and non-operative treatment groups. They also reported that 14 (54%) patients of the 26 with MM PRT showed progression to total knee replacement at a mean period of 54.3 months. Han et al. reported that 9 (19%) of their 46 patients with MM PRT underwent reoperation, and those who had advanced arthritic change preoperatively had poor clinical outcomes [25]. However, these were not large population studies with long-term results, and results were not compared according to the types of MM tear. A similar failure rate of APM, in 30 (27.3%) of the 110 patients with MM PRT and in 35 (31.8%) of the 110 patients with MM NRT, showed after adjustments for confounding variables in this study.

Numerous risk factors are involved in the incidence and progression of knee osteoarthritis, such as age, gender, obesity, alignment, history of trauma, and level of activities [12, 14, 22, 26]. Moreover, whether a significant correlation exists between osteoarthritic changes in radiographs and clinical symptoms remains unclear [10, 43]. In fact, APM of MM PRT clearly cannot restore the normal biomechanics of the knee joint and prevent osteoarthritis progression. In the present study, the natural course of APM was analyzed according to the type of degenerative MM tear after adjustments for confounding variables such as age, gender, BMI, alignment, and cartilage status of the medial compartment, using propensity score matching analysis. Contrary to our expectation, similar joint survival and clinical outcome after APM were shown between MM PRT and MM NRT. Several factors probably affect the prognosis after partial meniscectomy, and joint failure and clinical outcome after surgery may not be drastically determined according to the meniscal tear type only.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study with potential selection bias. Propensity score matching was used in this study to control for confounding variables. This led to the exclusion of unmatched patients in both groups from the analysis. On the other hand, through propensity score matching, we could compare how homogeneous groups such as those in prospective studies. Second, alignment as a confounding factor was measured in the anatomical axis on standing AP radiographs, not in the mechanical axis on whole-leg radiographs. Third, joint survival was assessed on the basis of surgical and radiographic failures. Other factors for reoperation or the patient’s clinical symptoms were not considered. Thus, joint survival could vary according to the definition of failure. Fourth, we did not investigate the radiological outcomes or features of osteoarthritis between the two groups. This topic could be studied in the future. Fifth, the MM tear morphology was only classified into two groups, MM PRT and MM NRT. Thus, we could not analyze the effect of the detailed subtypes of meniscal tear. Different tear patterns obviously have different biomechanical consequences. However, only comparative analysis of MM PRT and MM NRT was attempted in this study. Moreover, the detailed types of NRT were difficult to accurately distinguish because most degenerative tears have complex patterns and more than one tear component. Sixth, the effect of resection amount after partial medial meniscectomy was not assessed.

Conclusion

In middle-aged patients with degenerative MM PRT, joint survival and clinical outcome showed comparable results with those with MM NRT after partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is one of the effective treatments for MM PRT with consideration of various patient factors.

References

Adams JG, McAlindon T, Dimasi M, Carey J, Eustace S (1999) Contribution of meniscal extrusion and cartilage loss to joint space narrowing in osteoarthritis. Clin Radiol 54(8):502–506

Ahn JH, Jeong HJ, Lee YS, Park JH, Lee JW, Park JH, Ko TS (2015) Comparison between conservative treatment and arthroscopic pull-out repair of the medial meniscus root tear and analysis of prognostic factors for the determination of repair indication. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135(9):1265–1276

Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD (2008) Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus. Similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Jt Surg Am 90(9):1922–1931

Anderson AF, Irrgang JJ, Dunn W, Beaufils P, Cohen M, Cole BJ, Coolican M, Ferretti M, Glenn RE Jr, Johnson R, Neyret P, Ochi M, Panarella L, Siebold R, Spindler KP, Ait Si Selmi T, Verdonk P, Verdonk R, Yasuda K, Kowalchuk DA (2011) Interobserver reliability of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 39(5):926–932

Austin PC (2008) A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003. Stat Med 27(12):2037–2049

Austin PC (2009) Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput 38(6):1228–1234

Austin PC (2011) An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res 46(3):399–424

Beaufils P, Becker R, Kopf S, Englund M, Verdonk R, Ollivier M, Seil R (2017) Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions: The 2016 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Joints 5(2):59–69

Beaufils P, Becker R, Kopf S, Englund M, Verdonk R, Ollivier M, Seil R (2017) Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions: the 2016 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25(2):335–346

Bedson J, Croft PR (2008) The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9:116

Bin SI, Kim JM, Shin SJ (2004) Radial tears of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy 20(4):373–378

Brouwer GM, van Tol AW, Bergink AP, Belo JN, Bernsen RM, Reijman M, Pols HA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM (2007) Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 56(4):1204–1211

Burks RT, Metcalf MH, Metcalf RW (1997) Fifteen-year follow-up of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy 13(6):673–679

Cerejo R, Dunlop DD, Cahue S, Channin D, Song J, Sharma L (2002) The influence of alignment on risk of knee osteoarthritis progression according to baseline stage of disease. Arthritis Rheum 46(10):2632–2636

Chatain F, Adeleine P, Chambat P, Neyret P (2003) A comparative study of medial versus lateral arthroscopic partial meniscectomy on stable knees: 10-year minimum follow-up. Arthroscopy 19(8):842–849

Chung KS, Ha JK, Ra HJ, Kim JG (2016) Prognostic factors in the midterm results of pullout fixation for posterior root tears of the medial meniscus. Arthroscopy 32(7):1319–1327

Elattrache N, Lattermann C, Hannon M, Cole B (2014) New England journal of medicine article evaluating the usefulness of meniscectomy is flawed. Arthroscopy 30(5):542–543

Englund M, Guermazi A, Lohmander SL (2009) The role of the meniscus in knee osteoarthritis: a cause or consequence? Radiol Clin North Am 47(4):703–712

Fabricant PD, Jokl P (2007) Surgical outcomes after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 15(11):647–653

Fairbank TJ (1948) Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Jt Surg Br 30b(4):664–670

Faucett SC, Geisler BP, Chahla J, Krych AJ, Kurzweil PR, Garner AM, Liu S, LaPrade RF, Pietzsch JB (2019) Meniscus root repair vs meniscectomy or nonoperative management to prevent knee osteoarthritis after medial meniscus root tears: clinical and economic effectiveness. Am J Sports Med 47(3):762–769

Felson DT (1990) The epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: results from the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 20(3 Suppl 1):42–50

Feucht MJ, Kuhle J, Bode G, Mehl J, Schmal H, Sudkamp NP, Niemeyer P (2015) Arthroscopic transtibial pullout repair for posterior medial meniscus root tears: a systematic review of clinical, radiographic, and second-look arthroscopic results. Arthroscopy 31(9):1808–1816

Habata T, Uematsu K, Hattori K, Takakura Y, Fujisawa Y (2004) Clinical features of the posterior horn tear in the medial meniscus. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 124(9):642–645

Han SB, Shetty GM, Lee DH, Chae DJ, Seo SS, Wang KH, Yoo SH, Nha KW (2010) Unfavorable results of partial meniscectomy for complete posterior medial meniscus root tear with early osteoarthritis: a 5- to 8-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy 26(10):1326–1332

Heidari B (2011) Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Casp J Intern Med 2(2):205–212

Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S (2007) Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 15(4):393–401

Hulet CH, Locker BG, Schiltz D, Texier A, Tallier E, Vielpeau CH (2001) Arthroscopic medial meniscectomy on stable knees. J Bone Jt Surg Br 83(1):29–32

Hwang BY, Kim SJ, Lee SW, Lee HE, Lee CK, Hunter DJ, Jung KA (2012) Risk factors for medial meniscus posterior root tear. Am J Sports Med 40(7):1606–1610

Jiang EX, Abouljoud MM, Everhart JS, DiBartola AC, Kaeding CC, Magnussen RA, Flanigan DC (2019) Clinical factors associated with successful meniscal root repairs: as systematic review. Knee 26(2):285–291

Jones AO, Houang MT, Low RS, Wood DG (2006) Medial meniscus posterior root attachment injury and degeneration: MRI findings. Aust Radiol 50(4):306–313

Kan A, Oshida M, Oshida S, Imada M, Nakagawa T, Okinaga S (2010) Anatomical significance of a posterior horn of medial meniscus: the relationship between its radial tear and cartilage degradation of joint surface. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol 2:1

Kaplan DJ, Alaia EF, Dold AP, Meislin RJ, Strauss EJ, Jazrawi LM, Alaia MJ (2018) Increased extrusion and ICRS grades at 2-year follow-up following transtibial medial meniscal root repair evaluated by MRI. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26(9):2826–2834

Kim SB, Ha JK, Lee SW, Kim DW, Shim JC, Kim JG, Lee MY (2011) Medial meniscus root tear refixation: comparison of clinical, radiologic, and arthroscopic findings with medial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy 27(3):346–354

Krych AJ, Reardon PJ, Johnson NR, Mohan R, Peter L, Levy BA, Stuart MJ (2017) Non-operative management of medial meniscus posterior horn root tears is associated with worsening arthritis and poor clinical outcome at 5-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25(2):383–389

Krych AJ, Johnson NR, Mohan R, Dahm DL, Levy BA, Stuart MJ (2018) Partial meniscectomy provides no benefit for symptomatic degenerative medial meniscus posterior root tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26(4):1117–1122

LaPrade CM, James EW, Cram TR, Feagin JA, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF (2015) Meniscal root tears: a classification system based on tear morphology. Am J Sports Med 43(2):363–369

Lee BS, Bin SI, Kim JM, Park MH, Lee SM, Bae KH (2019) Partial meniscectomy for degenerative medial meniscal root tears shows favorable outcomes in well-aligned, nonarthritic knees. Am J Sports Med 47:606–611

Lee DH, Kim TH, Kim JM, Bin SI (2009) Results of subtotal/total or partial meniscectomy for discoid lateral meniscus in children. Arthroscopy 25(5):496–503

Lee DW, Moon SG, Kim NR, Chang MS, Kim JG (2018) Medial knee osteoarthritis precedes medial meniscal posterior root tear with an event of painful popping. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 104(7):1009–1015

Lee JH, Lim YJ, Kim KB, Kim KH, Song JH (2009) Arthroscopic pullout suture repair of posterior root tear of the medial meniscus: radiographic and clinical results with a 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 25(9):951–958

Lerer DB, Umans HR, Hu MX, Jones MH (2004) The role of meniscal root pathology and radial meniscal tear in medial meniscal extrusion. Skeletal Radiol 33(10):569–574

Magnusson K, Kumm J, Turkiewicz A, Englund M (2018) A naturally aging knee, or development of early knee osteoarthritis? Osteoarthr Cartil 26(11):1447–1452

Papalia R, Del Buono A, Osti L, Denaro V, Maffulli N (2011) Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Br Med Bull 99:89–106

Ra HJ, Ha JK, Jang HS, Kim JG (2015) Traumatic posterior root tear of the medial meniscus in patients with severe medial instability of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(10):3121–3126

Rangger C, Klestil T, Gloetzer W, Kemmler G, Benedetto KP (1995) Osteoarthritis after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med 23(2):240–244

Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, Benjamin JB, Lonner JH, Scott WN (2012) The new Knee Society Knee Scoring System. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(1):3–19

Seo HS, Lee SC, Jung KA (2011) Second-look arthroscopic findings after repairs of posterior root tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med 39(1):99–107

Zampogna B, Vasta S, Amendola A, Uribe-Echevarria Marbach B, Gao Y, Papalia R, Denaro V (2015) Assessing Lower limb alignment: comparison of standard knee X-ray vs long leg view. Iowa Orthop J 35:49–54

Funding

No funding was required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was given by the Ethics Committee of Asan Medical Center.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

IRB information: Approved by Asan Medical Center Institutional Review Board (Receipt number S2018-1857-0001, Project number 2018-1179).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, OJ., Bin, SI., Kim, JM. et al. Degenerative medial meniscus posterior root tear and non-root tear do not show differences in joint survival and clinical outcome after partial meniscectomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28, 3426–3434 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05771-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05771-1