Abstract

Traditionally, surgical stabilization of the unstable shoulder has been performed through an open incision. Arthroscopic Bankart repair with suture anchors is now widely considered the treatment of choice for anterior shoulder instability in patients who have failed conservative management. Many different factors have now been elucidated for adequate treatment of glenohumeral instability. Because of technical advances in instability repair combined with an increased understanding of factors that lead to recurrent instability, the outcomes following arthroscopic Bankart repair have significantly improved and approach those of open techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glenohumeral instability is very common in the general population, and many surgical techniques have been described for the treatment of this condition, each with different indications according to the pathological findings, patient age, sex and activity level [9–48]. Despite improvements in our understanding of the underlying pathology and surgical technique in treating shoulder instability, previous reports have suggested a risk of failure between 4 % and 30 % after primary surgical reconstruction with either arthroscopic or open techniques [6, 9, 15, 70]. This issue is likely in part related to the fact that anterior shoulder instability can be the result of one of several different types of underlying soft tissue lesions, ranging from a classic Bankart lesion to other variants such as a Perthes lesion or anterior labroligamentous periosteal sleeve avulsion (ALPSA lesion). A Bankart lesion may be an isolated soft tissue avulsion or may involve a fracture of the anteroinferior glenoid rim, commonly referred to as a “bony Bankart”. The Perthes and ALPSA lesions are variants of the Bankart lesion. A Perthes lesion is characterized by an avulsion of the anterior labrum from the anterior–inferior glenoid which is attached to stripped but still intact medial scapular periosteum. Although an ALPSA lesion has been described as a “medialized Bankart lesion”, it is similar to a Perthes in that the disrupted labrum remains attached to the medial scapular periosteum. This allows the labrum to heal in a more medialized position along the glenoid neck, which is the defining characteristic of the ALPSA lesion. Another variant commonly referred to as a glenolabral articular disruption (GLAD lesion) is an anteroinferior labral tear along with an associated defect in the articular cartilage. In this injury, the torn labrum remains attached to the medial scapular periosteum; however, there is the addition of an adjacent articular cartilage injury.

In chronic anterior shoulder instability, associated intraarticular lesions are more frequent compared with first-time dislocators, which is probably a result of repeated dislocation or subluxation episodes [76]. Therefore, it is essential to be precise in the analysis of the anterior shoulder instability pattern in order to select the most optimal treatment. In consequence, the gold standard of arthroscopic treatment is related to the correct understanding of the pathologic lesion(s) and is unique to each individual patient.

Historical perspective

With the advent of arthroscopy and rapid technical advances with improved implant choices, arthroscopic stabilization has very quickly become the desired method of primary treatment of traumatic shoulder instability. The first generation of arthroscopic treatment of anteroinferior instability using staples and transglenoid sutures generated a lot of enthusiasm because of the potential for anatomic fixation of the labrum to the glenoid [53]. In the 1988, Wiley studied the effectiveness of rivets for arthroscopic treatment of Bankart lesions [73]. The rivet was designed as a removable metallic device for affixing the torn labrum to the glenoid rim. It was removed after a period of 4–6 weeks. The rivet technique had the advantage of only penetrating the glenoid anteriorly, as opposed to a transglenoid suture technique, with decreased risk to the suprascapular nerve. However, with long-term follow-up the initial success rates were quite poor with recurrence rates approaching 50 % [28–31, 45, 49, 71, 72]. At that time several risk factors were determined to be statistically significant for recurrent instability following arthroscopic stabilization. Inadequate postoperative immobilization, bony Bankart lesions leading to “inverted pear” configurations, generalized ligamentous laxity, large and engaging Hill–Sachs lesions, contact or collision sports, young patient age and poor-quality soft tissue constraints have all been implicated as risk factors for arthroscopic failure [11, 33, 58, 59, 77]. However, at that time, it is also likely that suboptimal implants and surgical technique were also responsible for high recurrence rates [71].

The development of suture anchors has revolutionized the treatment of shoulder instability, and in contrast to initial studies, there have been recent reports of greater success rates following arthroscopic intervention. The many advantages of suture anchors for arthroscopic Bankart repair include multiple points of fixation, no posterior glenoid penetration and pull-out strength approaching that of transosseous sutures, especially when using modern generations of suture anchors. Bacilla et al. [4] reported a failure rate of only 9 % following arthroscopic reconstruction with suture anchors and nonabsorbable sutures in 40 consecutive young, high-demand athletes. Other retrospective studies have reported satisfactory results with a recurrence rate between 5 and 8 % using suture anchor techniques [27, 47, 55].

Cole et al. [18] included apprehension as well as subluxation and frank dislocation when comparing open and arthroscopic techniques and reported recurrence rates of 24 % in the arthroscopic group compared with 18 % in the open category. Sperber et al. [67] also reported on his short-term results comparing open and arthroscopic techniques, and although the arthroscopic technique was associated with a failure rate of 23 %, the open technique was associated with a failure rate of 12 %, again considerably higher than the traditional 3–4 % recurrence rate historically associated with open techniques. Kim et al. [39] reported no significant difference in outcome between the two groups with regard to recurrent instability rates. When including apprehension in the criteria for failure, then a recurrence rate of 10 and 10.2 % is reported for the open and arthroscopic groups, respectively. In assessing recurrent dislocations, the open group fared worse with an incidence of 6.7 % compared with 3.4 % in those treated arthroscopically. Other studies have shown no significant difference when comparing the results of arthroscopic and open stabilization in patients with an isolated Bankart lesion [25, 32].

Capsulolabral footprint

It has previously been noted that arthroscopic techniques place an emphasis on recreating the labral bumper effect by placing anchors on the glenoid rim but without attempting to restore the normal insertional anatomy [1]. Ahmad et al. demonstrated in a cadaveric study that the mean surface area of the native capsulolabral complex footprint was on average 256 mm2, whereas the native footprint of the labrum was on average 152.3 mm2. As a result, the labrum attachment comprised only 59 % of the overall capsulolabral complex. Some authors have tried to improve capsulolabral repair using different suture anchor configurations. At first, Lafosse et al. reported a technique of double-row labral repair, which was performed arthroscopically in 12 patients [42]. They described a double-row fixation technique with two suture anchors on the glenoid neck and three on the glenoid rim [42]. Recently, Moran et al. [52] described a different double-row technique proposed for shoulder instability in high-risk athletes without significant bone loss. Iwaso et al. described a series of patients undergoing a double-row technique with knotless anchors and sutures placed in a V-shaped pattern. They noted no recurrence of dislocation or subluxation in 19 joints followed for 24 months or longer [38].

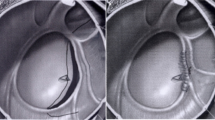

Other authors have proposed a double-row repair “flying swan” technique creating a “double-mattress” suture bridge medial to the glenoid margin that reinforces the buttress effect of the labrum and improves contact between the capsulolabral tissue and the underlying bone between the anchors [2]. The goal is to improve the footprint restoration at the level of the periosteal hinge. Furthermore, Castagna et al. [13] noted that in some patients with anterior shoulder instability there is not only a detensioning of capsulolabral tissue but also an attenuation or deficiency of this tissue that can appear very thin and inconsistent. Simple suture anchor repair in these cases can lead to early failure; they proposed the MIBA stitch (a combination of a mattress and single stitch) to restore good tone in the capsular tissue, rebuild the labrum on the face of the glenoid and improve the grip of the stitch in the attenuated capsulolabral tissue [13]. All these ideas represent further attempts to improve soft tissue arthroscopic Bankart repair in cases of shoulder instability in order to reach a gold standard of repair. However, at this moment prospective clinical studies are lacking to allow for such conclusions.

Failed arthroscopic stabilization and algorithm of management

Arthroscopic management of glenohumeral instability has the potential to be just as successful as open procedures if the surgeon is able to recognize and address all underlying relevant contributory pathology. For many years, surgeons evaluating the recurrence rates after arthroscopic capsulorrhaphy have recognized that untreated or unrecognized capsular tears and deformation represent the most common cause of failure after arthroscopic Bankart repair [13, 50, 66]. While improvements in surgical technique have helped reduce the risk of recurrent instability, it is also probable that many failures after arthroscopic stabilization can be attributed to inappropriate patient selection. Many different risk factors for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation have previously been described in the literature including younger patient age, participation in contact sports activities, the presence of an engaging Hill–Sachs or osseous Bankart lesion, ipsilateral rotator cuff or deltoid muscle insufficiency, and underlying ligamentous laxity [13, 55]. Ramsey et al. [64] reported that traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder is associated with a high rate of recurrence in young patients. According to Porcellini et al. [62], age at the time of the first dislocation, male sex and the time between the first dislocation and surgery are predictive of failure after arthroscopic Bankart repair. Generalized ligamentous laxity, higher patient level of activity and reduced compliance with the postoperative management are all likely causative factors related to the high recurrence rate in this age group [35].

However, in a prospective multicentre clinical study with 25 years of follow-up no significant differences in recurrent instability with respect to gender were demonstrated [36]. Levine et al. [43] have identified that most causes of unsuccessful shoulder stabilization relate to the failure to adequately correct an excessively large anterior–inferior capsular pouch and detached capsulolabral complex. It has also been previously shown that there is a nonrecoverable strain field of the anteroinferior capsulolabral complex associated with multiple episodes of shoulder subluxation or dislocations [44]. Furthermore, the capsular tissue itself can have a poor overall quality related to multiple dislocations or with generalized ligamentous laxity [8]. Burkhart and De Beer [12] have stressed the importance of reconstructing bony defects during arthroscopic procedures. According to their findings, the arthroscopic Bankart repair is capable of delivering the same results in terms of recurrence as an open Bankart procedure in the absence of significant bony defects. Tauber et al. [68] demonstrated that half of patients requiring revision surgery had a bony Bankart defect extending to the anterior–inferior glenoid straight downward from the glenoid notch. It is important, however, to distinguish patients with loss of contour of the anterior glenoid related to attritional bone loss and those with a glenoid bone avulsion fracture. Patients with an eroded anterior glenoid often have an associated attenuation of the anterior–inferior capsulolabral complex. The deficiency of this structure allows for recurrent subluxations or dislocations that contribute to further erosion of the anterior–inferior glenoid. Boileau et al. [9] noted that avulsion fracture did not represent an identifiable risk factor for failure following arthroscopic Bankart repair. Most authors agree that in cases involving a deficiency of <20 % of the glenoid bone an arthroscopic revision repair can be done with good outcomes particularly in patients not involved in contact sports [3, 7, 51, 63]. However, if bone loss is >20 % of the glenoid surface, surgical treatment should ideally include a bony reconstruction procedure.

Although unrecognized glenoid bone loss is a common cause of recurrent instability, an engaging Hill–Sachs lesion can also be a cause of recurrent instability [46]. A Hill–Sachs lesion has been demonstrated in as high as 90–100 % of patients with shoulder instability [69]. Most defects are small and have little effect on the stability of the shoulder. Burkhart et al. [11] at first used the term “engaging Hill–Sachs lesion” to describe a compression fracture on the posterosuperior aspect of the humeral head which drops over the glenoid rim in external rotation of an abducted shoulder and is associated with recurrent instability. It has been shown that patients with dislocations associated with an engaging Hill–Sachs lesion were at high risk of recurrence if treated with a classic arthroscopic capsuloligamentous repair, confirming that satisfactory restoration of the anterior–inferior soft tissue structures alone would not be sufficient to contain the humeral head under stress [11].

Recently, Yamamoto et al. [75] examined the relationship between the Hill–Sachs lesion and the glenoid, thereby introducing the “glenoid track” concept. The glenoid track is zone of contact between the glenoid and the humeral head that is modified according to the position of the arm [75]. The integrity of the glenoid track and the location of the Hill–Sachs lesion become essential in identifying patients with bipolar lesions who are at risk of recurrence following isolated Bankart repair. Kurokawa et al. [41] defined the “true engaging Hill–Sachs lesion” as either one that engages after Bankart repair or one that extends over the glenoid track. In this sense, it is very important to identify the position of the Hill–Sachs lesion, to understand whether the lesion could be engaging or not engaging. As a result, the intraoperative dynamic evaluation of the Hill–Sachs lesion should always be performed before performing Bankart repair. However, this diagnostic technique could potentially lead to over treatment of engaging Hill–Sachs lesions, as ligamentous insufficiency might permit the humeral head to excessively translate anteriorly, thus facilitating engagement of the humeral defect with the glenoid rim. The glenoid track can also be studied on pre-operative imaging and could be useful for the surgeon to decide the surgical strategy.

Taking into account all the previously cited factors, some authors have proposed an algorithm of surgical management of shoulder instability. Balg and Boileau [5] proposed a simple ten-point scale instability severity index score (ISIS) based on factors derived from a preoperative questionnaire, physical examination and anteroposterior radiographs to determine the risk of recurrence following isolated arthroscopic Bankart repair. This scoring system takes into account the age and level of activity of the patient, the presence of hyperlaxity and the presence of either a Hill–Sachs lesion or loss of glenoid contour on plain radiographs. In this model, a score of 3 or less was associated with a 5 % rate of recurrence, a score of 4–6 was associated with a 10 % rate of recurrence, and a score over 6 was associated with a 70 % rate of recurrence after an isolated Bankart repair. Although it has inherent weaknesses, the ISIS provides an algorithm to guide the treating surgeon in order to attempt to minimize the risk of recurrent instability following surgical reconstruction [65].

Bankart repair as gold standard

Surgical management should be based on patient factors and associated pathology as previously discussed. Patients who demonstrate preoperative risk factors for recurrent instability may require a different surgical approach other than arthroscopic Bankart repair. However, arthroscopic Bankart repair can be as successful as open procedures if the surgeon is able to recognize all underlying soft tissue deficiency and treat them appropriately. Certain rules should be respected when performing arthroscopic Bankart repair in order to obtain the best possible outcomes and minimize the risk of recurrent instability.

Number of anchors and capsular shift

It was previously believed that a minimum of three double-loaded suture anchors had to be used in order to obtain a satisfactory capsular shift [9]. However, a recent study demonstrated that one to two anchors could be enough [74]. This depends on the type of injury, and one must take caution with the position of the anchors. An ALPSA lesion is better identified from the anterosuperior portal, and it must be mobilized and appropriately tensioned on the face of the glenoid.

Arthroscopic portals

When surgeon is performing an arthroscopic Bankart repair, proper portal placement is crucial for success in labral and capsular preparation, anchor placement and to get the tissue at right zone to achieve an appropriate tensioning of the capsular ligament. Positioning for arthroscopic stabilization should be determined by surgeon preferences as both beach-chair and lateral decubitus positioning can achieve excellent visualization. For lateral decubitus positioning, usually dual anterior portals are established, with the anterior–inferior or middle glenoid portal directly superior to the upper margin of the subscapularis tendon and the anterosuperior portal placed at the superior border of the rotator interval, directly behind the biceps tendon. A standard posterior portal is created at first slightly lateral to and above the glenoid rim. This permits the posterior portal to be a viewing or working portal without interference from the glenoid rim. Standard arthroscopic portals could provide insufficient visualization and instrumentation access to inferior glenoid. In anteroinferior instability, very often there is a capsular redundancy, particularly at level of the axillary pouch (capsule between anteroinferior and posteroinferior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex). For this reason, the inferior anchor is crucial because emphasis should be not only on anatomic suture anchor repair of the capsuloligamentous disruption but also adequate inferior to superior capsular shift to eliminate the redundant inferior capsular pouch [20]. Some authors have described the use of an accessory posterolateral portal as located 4 cm lateral to the posterolateral corner of the acromion, for placement of the inferior suture anchor to perform capsulolabral repair. According to these authors, the advantages of the posterolateral portal are enhanced ability to place anchors in the inferior glenoid at an improved trajectory, improved anteroinferior knot tying, facilitation of anteroinferior labral repair and anatomic reduction in the inferior glenohumeral ligament [21].

In case of beach-chair position, again two anterior and one posterior portal are used. Imhoff et al. [37] proposed the use of a 5:30 o’clock to improve refixation and plication of the inferior glenohumeral ligament complex. According to the authors, this deep anterior–inferior portal could be very useful to place the lowest anchor (5:30 o’clock) and repair the most inferior portion of the capsulolabral complex.

Suture knots

When the surgeon uses a suture anchors technique, suture knots that are able to augment the tissue grip or capsulolabral footprint should be used in selected cases to improve footprint between capsulolabral tissue and glenoid neck [13]. Nowadays multiple knotless anchor options are available to perform arthroscopic Bankart repair. Since the introduction of the knotless anchor, several studies have examined the results of the use of these anchors in the treatment of shoulder instability. Satisfactory results at short-term follow-up are reported by different clinical studies [26, 34]. Kocaoglu et al. [40] prospectively compared the outcomes of 20 arthroscopic Bankart repair with knotless anchors with 18 repairs with traditional anchor sutures technique and found no significant differences between the two groups. Oh e al. felt that these anchors may offer improved capsulolabral repair by compressing the repaired tissue to bone to a greater extent than traditional anchors, which would lead to more secure fixation. However, they noted that the repair with this device requires a more precisely capture of the correct amount of tissue to achieve proper tissue tension owing to the fixed length of the anchor loop respect to the traditional anchor [56].

Other authors pointed out that the repair with a suture anchors—with or without knot—can result in a concentrated point load of the reduced labrum to the glenoid at each suture anchor. They describe the use of LabralTape to provide secure fixation of the labral tissue across the fixation, between each suture anchor, and to obtain a more uniform pressure distribution of the entire labrum (Labral bridge technique) [57].

Plications

Arthroscopic plication sutures should be used in cases where there is a need to reduce the capsular volume. In a cadaver study, arthroscopic anterior plication resulted in a 22.8 % reduction in capsular volume, whether open capsular shift resulted in a 49.9 % volume reduction [17]. The reduction in capsular volume is dependent on the number of plicating suture as demonstrated by Ponce et al. [61]. Closure of the rotator interval continues to be a source of controversy in arthroscopic instability surgery. Some authors recommend using this technique for patients with hyperlaxity and recurrent instability or inpatients with a positive sulcus sign that does not correspond to the contralateral side or cannot be corrected by external rotation with the arm at side. Closure of the rotator interval can improve anterior instability while simultaneously leading to a loss of external rotation [16]. On the other hand, in selected cases a posterior inferior capsular plication associated with anterior Bankart repair can be performed [14].

Glenoid bone defect

Isolated Bankart repair is generally not sufficient in the surgical management of the patients with bone defect. However, not all the bone loss are the same. Fracture should be differentiated by the erosion bone loss. In case of anterior glenoid bone erosion with a deficiency of <20 % of entire surface, without an engaging or off-track Hill–Sachs lesion, a simple Bankart repair could be still an available option. In case of bone defect with glenoid bony Bankart or fracture, an all arthroscopic repair of a bony Bankart lesion with incorporation of the bony fragment in the repair has had acceptable results [78]. Park et al. [60] reported that following arthroscopic fixation of the glenoid fracture in its anatomic position, fragments unite and survive without resorption at 1 year.

Humeral head lesions

Bankart repair combined with Hill–Sachs remplissage for large defects of the posterosuperior aspect of the humeral head may be a useful approach in cases of isolated humeral defect without glenoid bone loss. Remplissage has been described by Connolly [19] and may be used in the setting of a large Hill–Sachs lesion with glenoid bone loss of <25 % and when the lesion is considered to be offtrack [23]. This technique consists of a posterior capsulodesis incorporating the infraspinatus that fills the Hill–Sachs lesion. The purpose is to render the Hill–Sachs lesion extracapsular, thereby avoiding engagement with the anterior glenoid rim. Boileau et al. [10] reported that arthroscopic Hill–Sachs remplissage procedure in combination with Bankart repair in the treatment of patients with a large bony defect on the humeral head was an effective method. The authors also concluded that 98 % of the patients had a stable shoulder joint at final follow-up with approximately 10 degrees of restriction in external rotation which did not significantly affect return to sports activity. However, patients should be informed that as many as 33 % of cases have been associated with posterosuperior pain following remplissage [54].

Conclusion

Because of technical advances in instability repair, arthroscopic Bankart repair is becoming more commonly performed, with outcomes approaching those of open repair. Arthroscopic Bankart stabilization with use of suture anchors offers the advantage of being minimally invasive, allows adequate assessment of associated pathology and allows the surgeon to reattach the capsulolabral tissues and retension the inferior glenohumeral ligament. Arthroscopic reconstruction can have excellent results in terms of recurrence and function if close attention is paid to all relevant preoperative and intraoperative details.

References

Ahmad CS, Galano GJ, Vorys GC, Covey AS, Gardner TR, Levine WN (2009) Evaluation of glenoid capsulolabral complex insertional anatomy and restoration with single- and double-row capsulolabral repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 18:948–954

Alexander S, Al Wallace (2014) The “flying swan” technique: a novel method for anterior labral repair using a tensioned suture bridge. Arthrosc Tech 3(1):e119–e122

Arce G, Arcuri F, Ferro D, Pereira E (2012) Is selective arthroscopic revision beneficial for treating recurrent anterior shoulder instability? Clin Orthop Relat Res 479(4):965–971

Bacilla P, Field LD, Savoie FH (1997) Arthroscopic Bankart repair in a high demand patient population. Arthroscopy 13:51–60

Balg F, Boileau P (2007) The instability severity index score. A simple pre-operative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89(11):1470–1477

Barnes CJ, Getelman MH, Snyder SJ (2009) Results of arthroscopic revision anterior shoulder reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 37:715–719

Bartl C, Schumann K, Paul J, Vogt S, Imhoff AB (2011) Arthroscopic capsulolabral revision repair for recurrent anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 39:511–518

Bedi A, Ryu RK (2010) Revision arthroscopic Bankart repair. Sports Med Arthrosc 18(3):130–139

Boileau P, Villalba M, Héry JY, Balg F, Ahrens P, Neyton L (2006) Risk factors for recurrence of shoulder instability after arthroscopic Bankart repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88(8):1755–1763

Boileau P, O’Shea K, Vargas P, Pinedo M, Old J, Zumstein M (2012) Anatomical and functional results after arthroscopic Hill–Sachs remplissage. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94:618–626

Burkhart SS, De Beer JF (2000) Traumatic glenohumeral bone defects and their relationship to failure of arthroscopic Bankart repairs: significance of the inverted-pear glenoid and the humeral engaging Hill–Sachs lesion. Arthroscopy 16:677–694

Burkhart SS, De Beer JF, Tehrany AM, Parten PM (2002) Quantifying glenoid bone loss arthroscopically in shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 18:488–491

Castagna A, Conti M, Moushine E, Delle Rose G, Massazza G, Garofalo R (2008) A new technique to improve tissue grip and contact force in arthroscopic capsulolabral repair: the MIBA stitch. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16:415–419

Castagna A, Borroni M, Rose Delle et al (2009) Effects of posterior-inferior capsular plications in range of motion in arthroscopic anterior Bankart repair: a prospective randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17(2):188–194

Castagna A, Garofalo R, Melito G, Markopoulos N, De Giorgi S (2010) The role of arthroscopy in the revision of failed Latarjet procedures. Musculoskelet Surg 94(suppl 1):S47–S55

Chechik O, Maman E, Dolkart O, Khashan M, Shabtai L, Mozes G (2010) Arthroscopic rotator interval closure in shoulder instability repair: a retrospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19(7):1056–1062

Cohen SB, Wiley W, Goradia VK et al (2005) Anterior capsulorrhaphy: an in vitro comparison of volume reduction. Arthroscopic plication versus open capsular shift. Arthroscopy 21:659–664

Cole BJ, L’Insalata J, Irrgang J, Warner JJP (2000) Comparison of arthroscopic and open anterior shoulder stabilization. J Bone Joint Surg 82:1108–1114

Connolly J (1972) Humeral head defects associated with shoulder dislocations. In: AAOS. Instructional course lectures. St. Louis, pp 42–54

Creighton RA, Romeo AA, Brown FM Jr et al (2007) Revision arthroscopic shoulder instability repair. Arthroscopy 23(7):703–709

Cvetanovich GL, McCormick F, Erickson BJ et al (2013) The posterolateral portal: optimizing anchor placement and labral repair at the inferior glenoid. Arthrosc Tech 2(3):e201–e204

Detrisac DA, Johnson LL (1986) Arthroscopic shoulder anatomy: pathologic and surgical implications. Slack, Thofare, pp 71–89

DiGiacomo G, Itoi E, Burkhart S (2014) Evolving concept of the Hill–Sachs lesion: from “engaging/non- engaging” lesion to “on-track/off-track” lesion. Arthroscopy 30(1):90–98

Edwards D, Howy G, Saies AD, Hayes MG (1994) Adverse reactions to an absorbable shoulder fixation device. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 3:230–233

Fabbriciani C, Milano G, Demontis A, Fadda S, Ziranu F, Mulas PD (2004) Arthroscopic versus open treatment of Bankart lesion of the shoulder: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy 20:456–462

Garofalo R, Mocci A et al (2005) Arthroscopic treatment of anterior shoulder instability using knotless suture anchors. Arthroscopy 21(11):1283–1289

Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM (2000) Arthroscopic treatment of anterior-inferior glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg 82:991–1003

Geiger D, Herley J, Tovey J et al (1993) Results of arthroscopic versus open Bankart suture repair. Ortho Trans 17:973

Grana WA, Buckley PD, Yates CK (1993) Arthroscopic Bankart suture repair. Am J Sports Med 21:348–353

Green MR, Christensen KP (1995) Arthroscopic Bankart repair: two to five year follow-up with clinical correlation to severity of glenoid labral lesion. Am J Sports Med 23:276–281

Guanche CA, Quick DC, Sodergren KM et al (1996) Arthroscopic versus open reconstruction of the shoulder in patients with isolated Bankart lesions. Am J Sports Med 24:144–148

Harris JD, Gupta AK, Mall NA et al (2013) Long-term outcomes after Bankart shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy 29(5):920–933

Hayashida K, Yoneda M, Nakagawa S et al (1998) Arthroscopic Bankart suture repair for traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 14:295–301

Hayashida K, Yoneda M, Mizuno N, Fukushima S, Nakagawa S (2006) Arthroscopic Bankart repair with knotless suture anchor for traumatic anterior shoulder instability: results of short-term follow-up. Arthroscopy 22(6):620–626

Hovelius L (1996) Primary anterior dislocation of shoulder in the young patients. A ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78(11):1677–1684

Hovelius L, Olofsson A, Sandström B et al (2008) Nonoperative treatment of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in patients forty years of age and younger. A prospective twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:945–952

Imhoff AB, Ansah P, Tischer T et al (2010) Arthroscopic repair of anterior-inferior glenohumeral instability using a portal at the 5:30 o’clock position: analysis of the effects of age, fixation method, and concomitant shoulder injury on surgical outcomes. Am J Sports Med 38(9):1795–1803

Iwaso H, Uchiyama E, Sakakibara S, Fukui N (2011) Modified double-row technique for arthroscopic Bankart repair: surgical technique and preliminary results. Acta Orthop Belg 77:252–257

Kim S-H, Ha KI, Kim S-H (2002) Bankart repair in traumatic anterior shoulder instability: open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy 18:755–763

Kocaoglu B, Guven O, Nalbantoglu U, Aydin N, Haklar U (2009) No difference between knotless sutures and suture anchors in arthroscopic repair of Bankart lesions in collision athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17(7):844–849

Kurokawa D, Yamamoto N, Nagamoto H et al (2013) The prevalence of a large Hill–Sachs lesion that needs to be treated. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22(9):1285–1289

Lafosse L, Baier GP, Jost B (2006) Footprint fixation for arthroscopic reconstruction in anterior shoulder instability: the Cassiopeia double-row technique. Arthroscopy 22:231.e1–231.e6

Levine WN, Arroyo JS, Pollock RG et al (2000) Open revision stabilization surgery for recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability. Am J Sports Med 28:156–160

Malicky DM, Kuhn JE, Frisancho JC, Lindholm SR, Raz JA, Soslowsky LJ (2002) Neer Award 2001: non recoverable strain fields of the anteroinferior glenohumeral capsule under subluxation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 11(6):529–540

Manta JP, Organ S, Nirschl RP et al (1997) Arthroscopic transglenoid suture capsulolabral repair. Am J Sports Med 25:614–618

Miniaci A, Gish MW (2004) Management of anterior glenohumeral instability associated with large Hill–Sachs defects. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg 5:170–175

Mishra DK, Fanton GS (2001) Two-year outcome of arthroscopic Bankart repair and electrothermal-assisted capsulorrhaphy for recurrent traumatic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 17:844–849

Molé D, Villanueva E, Caudane H, De Gasperi M (2000) Results of more 10 years experience of open procedures. Rev Chir Reparatrice Appar Mot 86(1):111–114

Mologne TS, Lapoint JM, Morin WD et al (1996) Arthroscopic anterior labral reconstruction using a transglenoid suture technique: results in active duty military patients. Am J Sports Med 24:268–274

Mologne TF, McBride MT, Lapoint JM (1997) Assessment of failed arthroscopic anterior labral repairs: findings at open surgery. Am J Sports Med 25:813–817

Mologne TS, Provencher MT, Menzel KA et al (2007) Arthroscopic stabilization in patients with an inverted pear glenoid: results in patients with bone loss of the anterior glenoid. Am J Sports Med 35(8):1276–1283

Moran CJ, Fabricant PD, Kang R, Cordasco FA (2006) Arthroscopic double-row anterior stabilization and Bankart repair for the “high-risk” athlete. Arthroscopy 22(2):231.e1–231.e6

Morgan CD, Bodenstab AB (1987) Arthroscopic Bankart suture repair: technique and early results. Arthroscopy 3(2):111–122

Nourissat G, Kilinc AS, Werther JR, Doursounian L (2011) A prospective, comparative, radiological, and clinical study of the influence of the “remplissage” procedure on the shoulder range of motion after stabilization by arthroscopic Bankart repair. Am J Sports Med 39(10):2147–2152

O’Neill DB (1999) Arthroscopic Bankart repair of anterior detachments of the glenoid labrum. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:1357–1366

Oh JH, Lee HK, Kim JY, Kim SH, Gong HS (2009) Clinical and radiological outcomes of arthroscopic glenoid labrum repair with the bioknotless suture anchor. Am J Sports Med 37(12):2340–2348

Ostermann RC, Hofbauer M, Platzer P, Moen TC (2015) The labral bridge A novel technique for arthroscopic anatomic knotless Bankart repair. Arthrosc Tech 4(2):e91–e95

Pagnani MJ, Warren RF, Altchek DW et al (1996) Arthroscopic shoulder stabilization using transglenoid sutures: a four-year minimum follow-up. Am J Sports Med 24:459–467

Pagnani MJ, Dome DC (2002) Surgical treatment of traumatic anterior shoulder instability in American football players. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84:711–715

Park JY, Lee SJ, Lhee SH, Lee SH (2012) Follow-up computed tomography arthrographic evaluation of bony Bankart lesions after arthroscopic repair. Arthroscopy 28:465–473

Ponce BA, Rosenzweig SD, Thompson KJ, Tokish J (2011) Sequential volume reduction with capsular plications: relationship between cumulative size of plications and volumetric reduction for multidirectional instability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med 39(3):526–531

Porcellini G, Campi F, Pegreffi F, Castagna A, Paladini P (2009) Predisposing factors for recurrent shoulder dislocations after arthroscopic treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(11):2537–2542

Provencher MT, Arciero RA, Burkhart SS, Levine WN, Ritting AW, Romeo AA (2010) Key factors in primary and revision surgery for shoulder instability. Instr Course Lect 59:227–244

Ramsey ML, Getz CL, Parsons BO (2010) What’s new in shoulder and elbow surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:1047–1061

Rouleau DM, Hebert-Davies J, Djahangiri A, Godbout V, Pelet S, Balg F (2013) Validation of the instability shoulder index score in a multicenter reliability study in 114 consecutive cases. Am J Sports Med 41(2):278–282

Speer KP, Warren RF, Pagnani M et al (1996) An arthroscopic technique for anterior stabilization of the shoulder with a bioabsorbable tack. J Bone Joint Surg 1996(78A):1801–1807

Sperber A, Hamberg P, Karlsson J et al (2001) Comparison of an arthroscopic and an open procedure for posttraumatic instability of the shoulder: a prospective randomized multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 10:105–108

Tauber M, Resch H, Forstner R, Raffl M, Schauer J (2004) Reasons for failure after surgical repair of anterior instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 13(3):279–285

Taylor DC, Arciero RA (1997) Pathologic changes associated with shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopic and physical examination findings in first-time, traumatic anterior dislocations. Am J Sports Med 25:306–311

Tonino PM, Gerber C, Itoi E, Porcellini G, Sonnabend D, Walch G (2009) Complex shoulder disorders: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 17(3):125–136

Walch G, Boileau P, Levigne C et al (1995) Arthroscopic stabilization for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation: results of 59 cases. Arthroscopy 1:173–179

Weber SC (1991) A prospective evaluation comparing arthroscopic and open versus arthroscopic stabilization treatment of recurrent anterior glenohumeral dislocation. Orthop Trans 15:763

Wiley AM (1988) Arthroscopy for shoulder instability and a technique for arthroscopic repair. Arthroscopy 4(1):25–30

Witney-Lagen C, Perera N, Rubin S, Venkateswaran B (2014) Fewer anchors achieves successful arthroscopic shoulder stabilization surgery: 114 patients with 4 years of follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 23(3):382–387

Yamamoto N, Itoi E, Abe H et al (2007) Contact between the glenoid and the humeral head in abduction, external rotation, and horizontal extension: a new concept of glenoid track. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 16(5):649–656

Yiannakopoulos CK, Mataragas E, Antonogiannakis E (2007) A comparison of the spectrum of intra-articular lesions in acute and chronic anterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy 23(9):985–990

Youssef JA, Carr CF, Walther CE et al (1995) Arthroscopic Bankart suture repair for recurrent traumatic unidirectional anterior shoulder dislocations. Arthroscopy 11:561–563

Zhu YM, Jiang CY, Lu Y, Xue QY (2011) Clinical results after all arthroscopic reduction and fixation of bony Bankart lesion. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 49(7):603–606

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castagna, A., Garofalo, R., Conti, M. et al. Arthroscopic Bankart repair: Have we finally reached a gold standard?. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24, 398–405 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3952-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3952-6