Abstract

Over the last decade, the economic literature has increasingly focused on the importance of gender identity and sticky gender norms in an attempt to explain the persistence of the gender gaps in education and labour market behaviour. Using detailed register data on the latest cohorts of Danish labour market entrants, this paper examines the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical choice of education. Although to some extent picking up inherited and acquired skills, our results suggest that if parents exhibit gender-stereotypical labour market behaviour, children of the same sex are more likely to choose a gender-stereotypical education. The associations are strongest for sons. Exploiting the detailed nature of our data, we use birth order and sibling sex composition to shed light on the potential channels through which gender differences in educational preferences are transmitted across generations. Our findings support the hypothesis that human capital transfers and intra-family resource allocation are important mechanisms. We find no evidence suggesting that school and/or residential location are important drivers of the documented intergenerational correlations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In most Western countries, women have successfully gained on men’s labour market position over the last 50 years. As a result, the gender gaps in labour force participation and wages have diminished; see for instance Kleven and Landais (2017). In a recent paper, Goldin (2014a) argues that the last chapter of the grand gender convergence is in the pipeline. Specifically, Goldin (2014a) suggests increasing labour market flexibility with respect to remuneration to and timing of working hours as a means to eliminate the remainder of the gender wage gap. Such change has already come about in several sectors, for example technology and health, while other sectors, such as corporate and legal, continue to lack behind. However, in the mid-1990s, the gender convergence stagnated and marked differences in pay, promotional patterns and types of activities performed by men and women still exist (Olivetti and Petrongolo 2016; World Economic Forum 2016).

One reason for this stagnation in gender convergence may be sticky social norms. To investigate this hypothesis, we estimate the intergenerational correlation in a measure of gender-stereotypical education choices, specifically the degree to which individuals select into female-dominated educational programmes. Investigating intergenerational transmission of gender attitudes can help improve the understanding of occupational gender segregation, which in turn may point to useful policy interventions to further gender equality in the labour market.

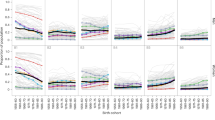

Reminiscent of Bertrand et al. (2015) and Goldin (2014b), we suggest that, while previously somewhat neglected, male stereotypes are equally important factors of the remaining gender gaps. In particular, while women have assumed certain previously male-dominated educations, for example sociology and veterinary and agricultural sciences, there are no examples of a converse pattern.Footnote 1 As demonstrated in Fig. 1, women graduating in decidedly female-dominated fields on average earn less compared to women with degrees in male-dominated fields. However, unlike women, men face a reduction in expected earnings by entering less stereotypical fields as many female-dominated occupations are in the public sector and on average pay less.

This paper contributes to the literature on intergenerational transmission of education and gender gaps in earnings in four ways. First, we utilise administrative data on the entire population of recent college graduates in Denmark, which allows us to perform analyses of intergenerational correlation for cohorts that are highly relevant for current and future gender inequality. Older cohorts are at the end of their labour market career and therefore less relevant for the question of whether intergenerational transmission of gender-stereotypical behaviour contributes to the remaining gender gaps in the labour market.

Second, Denmark constitutes an interesting setting for this type of analysis being a country where female labour force participation is high and has been for decades. At the same time, occupational gender segregation is as large (or even larger) in Denmark as in other countries (Gupta and Smith 2002 and Gupta et al. 2008). Thus, substantial gender gaps in earnings remain as is also indicated by Fig. 1. Recent figures suggest that while the educational segregation for university college programmes has decreased somewhat in the recent decade, the educational segregation in higher university has increased despite a reversing gap in educational attainment (SFI 2016). Consequently, there is little hope that closing the gender gap in labour force participation or educational attainment will close the remaining gaps in occupational positions and earnings.

Third, we use the detailed individual-level data to construct different register-based measures of gender attitudes. We construct measures of gender attitudes in educational choices for both children and their parents allowing us to determine the intergenerational correlation in these measures. Further, we construct a register-based measure of parental attitudes that parallels the widely used survey question on gender norms “Do you agree with the statement that a man should earn more than his wife?” We focus on the important role that parents play in determining their children’s education choices rather than occupational choices. The choice of education is the first major decision individuals make concerning their future labour market career—often chosen prior to starting a family or entering the labour market. Thus, for a particular set of skills, we argue along the lines of Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik (2016) that choice of education, although indubitably an important determinant of subsequent occupation, is more immediately related to the preferences of individuals, whereas later labour market outcomes, such as occupation, promotion and earnings, to a greater extent reflect fertility and marriage decisions in addition to labour market conditions and employer discrimination.

Fourth, recognising that there are many potential mechanisms through which parent’s education choices may affect children’s education choices, we probe the importance of these channels in auxiliary analyses using different empirical strategies that allow us to eliminate some of the potential confounders. Most notably, we use different within-family strategies (see, e.g. Autor et al. 2017 and Brenøe and Lundberg forthcoming) to inform about the influence of birth order and sibling sex composition on the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical education choices which several studies suggest are potentially important (Lundberg 2005).

We document a positive and statistically significant correlation between parents and their children with respect to the share of females in education choice across generations. The same-sex correlations in the tendency to select into female-dominated educations across generations are dominant, whereas the mother-son and father-daughter correlations are generally smaller and in most cases insignificant. Interestingly, the father-son correlations seem strongest, less related to skill level and less sensitive across specifications. Additionally, the educational choices of daughters are to some extent correlated with the measures of gender-stereotypical behaviour of their fathers, while sons’ choices rarely correlate with the behaviour of their mothers. This may in part reflect the aforementioned difference in trade-offs faced by sons and daughters: Since wages are typically lower in women’s fields, there is a real trade-off for daughters between choosing (i) an education which is consistent with typical feminine norms but with lower expected future earnings or (ii) a less gender-congruent education but with higher expected earnings later in life. For sons, the “trade-off” is markedly different: choosing a gender-stereotypical education generally implies higher future earnings, while choosing a less gender-congruent education in a more female-dominated area would typically result in lower future earnings potential. Thus, it may be more difficult to change the gender-stereotypical behaviour of boys. Relatedly, we find that the gender gap in children’s gender-stereotypical education choice is wider for children of parents who exhibit more gender-stereotypical behaviour.

While the estimated intergenerational correlations can arguably arise due to many different mechanisms, we are able to add some insights on these. First, we find that intergenerational human capital transfers can explain part (but not all) of the intergenerational correlations. However, we establish intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical choice of education beyond the correlations that result because of children choosing the same education as their parents. Second, we establish interesting patterns within and across families, suggesting that resource allocation within families is an important driver of the intergenerational transmission. Finally, schools and residential location have little importance for the intergenerational correlations of gender-stereotypical education choice.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the literature on gender wage gaps and intergenerational transmissions. Section 3 introduces the data while Section 4 describes the estimation approach. Section 5 presents the main results while Section 6 explores potential mechanisms. Finally, Section 7 discusses and concludes.

2 Gender wage gaps and intergenerational transmissions

A vast economic literature on gender trends has explored the rise in female labour force participation following World War II; see, e.g. Goldin (2014a) and Olivetti and Petrongolo (2016) for recent and comprehensive descriptions. However, while Goldin (2014a) considers the diminishing gender wage gap as evidence of an impending final chapter of the gender convergence, Olivetti and Petrongolo (2016) note that the remaining gender gaps in several labour market outcomes, including college major choice, are remarkably persistent—particularly when considering the reversing gaps in educational attainment in many countries (although, the general progress in gender trends has slowed considerably since the mid-1990s, see, e.g. Blau and Kahn 2006; Olivetti and Petrongolo 2016).

Traditionally, the literature has focused on the changes in female gender roles to close the gender gaps. Studies by Maccoby (1998) support this in suggesting that the pressure of conforming to gender identity is greater for girls than boys, and Johnston et al. (2014) demonstrate that gender attitudes are transmitted from mothers to both daughters and sons, although only daughters’ labour market outcomes appear to be affected by this. Fernández et al. (2004), however, present evidence of changing societal norms in that wives of men whose mothers participated in the labour force during WWII are more likely to work themselves, and suggest that the operating channel is the change in norms of these men. Therefore, upholding male gender stereotypes may be an important factor in closing the remaining gender gaps (e.g. Goldin 2014b, Pan 2015, and Bordalo et al. (2016).

Parents have a considerable potential for influencing the education choice of their children: in a study of North-western University sophomores, Zafar (2013) finds that one of the greatest determinants of individuals’ college major choices is to gain the approval of their parents. Importantly, a prominent literature on intergenerational mobility documents considerable positive correlations between educational and occupational outcomes of parents and children (e.g. recent and comprehensive reviews by Björklund and Salvanes 2011; Black and Devereux 2011) where in particular the same-sex correlations appear strong. Although possibly also arising from other channels, this evidence is in line with inheritable or sticky social norms. Much of the literature concerning intergenerational evidence of occupation and education choice focus on the transmission of economic resources and human capital from parents to children, including information, networks and transfers of acquired and inheritable skills (e.g. Laband and Lentz 1992; Dunn and Holtz-Eakin 2000; Black and Devereux 2011; Corak and Piraino 2011). However, Lindquist et al. (2015) find that acquired skill transfers (post-birth factors) account for twice as much as inherited skills (pre-birth factors) when decomposing the intergenerational association in entrepreneurship using the Swedish adoption registers.

Such intergenerational transmissions are likely to cause positive associations in education and occupation choice across generations, although from an income-maximising perspective they alone cannot explain the dominant same-sex associations demonstrated in the empirical literature. A number of studies, however, show that parents tend to invest more in their same-sex children (Lundberg 2005), which potentially produces larger correlations along the same-sex dimension, although Grönqvist et al. (forthcoming) demonstrate that labour market outcomes for children of both sexes are equally and strongly related to the skills of both mothers and fathers.

Meanwhile there is growing evidence suggesting that gender norms transmitted from parents affect the labour market preferences of individuals. In accordance with the remarkable persistence in gender attitudes within cultures as demonstrated in Alesina et al. (2013), several papers find evidence that parents’ gender attitudes are related to women’s labour supply (Blau et al. 2013; Fernández et al. 2004; Fernández and Fogli 2009; Johnston et al. 2014). These inherited or transmitted stereotypes generate positive same-sex associations in education and occupation choices across generations and, consequently, the remaining gender gaps in field choices may be highly persistent. Even if parents do not deliberately transmit gender stereotypes to the next generation, children may acquire norms by observing gender roles in the household or the surrounding society. Based on the theory of role model identification, Ruef et al. (2003) suggest that role models are typically of the same sex (although the theory of same-sex role modelling extends far beyond the transfer of stereotypes—or even acquired skills), which may contribute to the dominant same-sex associations in the intergenerational literature.

We contribute to this literature by analysing the intergenerational correlation in measures of gender attitudes for the entire population of recent college graduates in Denmark using individual-level administrative data. Since we are able to construct measures of gender attitudes for both parents and children, we can test the hypothesis that gender attitudes are transmitted from one generation to the next, which may in turn explain the relationship found in previous studies between gender attitudes and female labour force participation. In addition, we are able to eliminate the main confounders in this type of analysis through (1) the inclusion of control variables (e.g. parental income and education and high school GPA), (2) the inclusion of school and municipality fixed effects and (3) analysis of within-family differences in gender attitudes. The latter is a substantial improvement compared to Johnston et al. (2014). Furthermore, we explore the role of birth order and sibling sex composition as potential channels of the intergenerational correlation.

3 Data, sample and descriptives

We exploit the detailed nature of the Danish administrative registers to collect information on actual education and labour market behaviour of the parents of entire population cohorts. From the birth registers, we identify all 1,133,658 children (cohort members) in Denmark born in 1970–1986. We further restrict the estimation sample to individuals for whom we can identify parents and parental country of origin. To obtain a homogenous sample of young adults and avoid, e.g. integration aspects, we focus on children whose parents are both of Danish ancestry, i.e. where both parents are born in Denmark and Danish citizens. Further, educational outcomes for the parent generation are generally more unreliable and to a large extent missing for immigrants. This leaves 949,862 observations; see Table 1.

Our main analyses are based on individuals obtaining at least a bachelor’s degree (BA) at age 28. This cut-off should leave plenty of time to finish a BA even including a couple of gap years, which are common for Danish students (Humlum 2007); compulsory school is generally completed at age 15. A three-year high school education (or alternatively two-year plus grade 10) qualifies for admission in most BA programmes. Table 1 shows that 27% of cohort members obtain at least a BA at or before age 28. As in most Western countries, female graduates dominate the BA programmes, although with large differences across fields: 62% of the individuals obtaining a bachelor’s degree are female. Table 1 also includes information on an alternative sample based on cohort members’ first enrolment in a BA education. First choice of enrolment likely reflects educational preferences with less consideration of the individual’s skill level. Therefore, we include first enrolment in a BA programme without conditioning on completion in our supplemental analyses.

3.1 Measuring gender-stereotypical education and labour market choices

We measure gender-stereotypical education choice for cohort members, FFi, as the share of female graduates in the education programme (a similar measure is used by Ancetol and Cobb-Clark 2013, and Hederos 2017) in the year the individual enrolled in the education programme. Thus, our outcome variable depicts the gender composition of the educational programme as observed by the individual when he or she applied to higher education.Footnote 2

The key explanatory variables are measures of the gender-stereotypical norms of the father and the mother or the parents taken together. Since we use register data, we do not have access to survey questionnaire responses on norms or attitudes. Instead, we use three alternative measures as proxies for stereotyping norms.

The first measure is parents’ gender-stereotypical education choice which is defined as the share of female graduates obtaining the parent’s degree at age 30 of the parents, not restricting the level of the highest attained degree (i.e. we also include compulsory school or vocational training).Footnote 3 If parents did not obtain a formal education, the fraction of females in the highest attained general education level (compulsory school or high school) is applied; see Appendix Fig. 2 for the distribution of parents’ gender-stereotypical education choice.

Our second measure of parents’ gender-stereotypical norms is the mother’s share of household earnings, as inspired by the behavioural prescription examined in Bertrand et al. (2015): “a man should earn more than his wife”. We define mother’s share of household earnings as HHshareMomi = EarningsMomi/(EarningsMomi + EarningsDadi). Traditional gender norms would prescribe the father’s status as breadwinner, and thus we would expect sons (daughters) to select into relatively more male-(female-) dominated fields the lower the HHshareMomi. We use the term household casually, as we do not condition on parents living together. Where both parents have zero earnings, we set HHshareMomi = 0 and define a dummy for zero total household earnings (see Appendix Fig. 3).

However, a large ratio of maternal to paternal earnings may on the one hand reflect that the mother is highly career-oriented (or at least successful in generating earnings) and on the other that the father is not a high-earner. These two explanations may have different implications if children predominantly reflect the behaviour of the same-sex parent as hinted previously. Thus, our third measure attempts to capture parental career ambitions individually as expressed in earnings deviations from their respective demographic groups (see Bertrand et al. 2015). For each individual i, we construct the potential earnings of both parents (PotentialMomi and PotentialDadi) as the mean of the earnings of working individuals in the mother’s or father’s demographic group. We assign demographic groups based on gender, a five-year age interval (due to incomplete information on graduation year, we are unable to use experience intervals) and education programme. We calculate deviations from potential (deflated) earnings for mothers and fathers at child age 15 as EarningsGapParenti = (EarningsParenti – PotentialParenti)/PotentialParenti, for Parenti = {mom, dad}.

Table 2 summarises the sample means of the various gender attitude measures. We note a marked difference in the gender compositions of sons’ and daughters’ BA programmes; on average, sons graduate in fields with almost 30 percentage points less females compared to daughters. The gender compositions of mothers’ and fathers’ obtained education are very similar for sons and daughters; however, there are slight differences in the mothers’ share of household earnings and the fathers’ earnings gap.

3.2 Control variables

We include a wide range of controls observed to capture cohort, region or family characteristics that may jointly affect parental labour market behaviour and cohort-member educational behaviour, see Table 3. Family and parental controls are measured at age 15 of the child, which coincides with the end of compulsory education and, thus, the beginning of tracking in the Danish education system.Footnote 4

Specifically, our vector of control variables includes the individual’s high school GPA to control for ability that is potentially correlated with both parental abilities and future labour market behaviour for the cohort member. The decision to attend high school is in itself likely based on future educational expectations and is as such not exogenous. It is, however a prerequisite for enrolling in most BA programmes.Footnote 5 We further control for parental educational attainment (compulsory, high school, vocational and higher education), log earnings, mother’s and father’s work hours (outside labour market, part-time or full-time), whether a parent died between age 15 and year of entry in tertiary education, number of siblings (children of the same mother) and older siblings of the same and opposite sex. In addition, we add a full set of indicators for year of birth, mother’s and father’s year of birth and residential municipality (at age 15). Specifically, birth year fixed effects for children and parents capture the general rise in the ratio of female to male BA graduates across years.

It is clear from Table 3 that we analyse a sample of recent college graduates which are characterised by high parental education levels (about 40% of parents have completed a higher education) and high maternal labour force participation (almost 90%), albeit roughly 20% of mothers are only working part-time. Not surprisingly, in the light of the considerable overweight of women in the BA programmes, Table 3 reveals that males in the sample are on average of slightly higher ‘quality’ than females: better high school GPAs, higher earnings as well as more highly educated parents.

4 Empirical methodology

We are interested in the important role that parents play in determining their children’s education choices and specifically how social norms may be transferred from parents to children. This is a challenging undertaking since the transmission of social norms and associated stereotypes are not readily quantifiable. Consequently, we take a more indirect approach and begin by estimating the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical choice of education. The transmission of social norms and in particular gender norms is one of several possible channels through which educational and occupational gender segregation persist across generations.

To estimate the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical choice of education, we specify the following reduced form model for individual i

where the outcome FF denotes measures of gender-stereotypical choice of education for sons and daughters. FFmom and FFdad denote measures of parental gender norms, which we operationalise via alternative register data measures, in particular, gender-stereotypical choice of education for parents (see Table 2). Xi are child and family characteristics presented in Section 3.2 and ui is the error term. The coefficients α1 and α2 reflect the mother-child and the father-child intergenerational correlations in female-dominated educational choices, respectively. Other transmissions affecting educational preferences, e.g. from peers and siblings, and other kinds of parental transfers not captured by the share of female graduates in the field of study or in the controls in Xi will be contained in ui. The results from Eq. (1) are partial correlations rather than causal effects and should only be interpreted as such.

Choice of educational field is considered a major determinant of labour market success in adulthood, but—as previously discussed—this choice likely reflects more immediate preferences and self-image of the individual compared to later labour market outcomes (Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik 2016). We therefore use education choice characteristics as our main outcome variable, but we can easily adjust the framework above to analyses of our other measures of gender-stereotypical choices.

The first step in our analysis is to test the hypothesis that parents’ education choices affect the education choices of their children, i.e. whether α1 and α2 differ significantly from zero. Acknowledging that determinants for education choice and that the influence of gender stereotypes potentially operate through different channels for sons and daughters (Blau et al. 2013; Johnston et al. 2014), we proceed by estimating Eq. (1) separately by gender.

The intergenerational correlation in our measure of stereotypical education choice likely picks up a range of factors related to the share of female graduates across generations other than gender norms, for example inherited and acquired comparative advantages in certain skills. We explore the importance of different mechanisms in Section 6.

5 Results

We aim to investigate the existence of intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical education and labour market behaviour and document interesting patterns focusing on gender differences. For this purpose, we first consider the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical education choice. Second, we analyse how parents’ gender-stereotypical education choices relate to the gender gap in gender-stereotypical education choice of children. Third, we consider alternative measures of gender-stereotypical choices in parental labour market behaviour and investigate how these measures relate to children’s gender-stereotypical education choice.

5.1 Intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical choice of education

To obtain an estimate of the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical (or female-dominated) choice of education, we estimate Eq. (1) with a full set of controls including indicators for year of birth and local geographical region (municipality). The key explanatory variables are the share of females in father’s education and the share of females in mother’s education. The explained variable is the share of females in the child’s education.Footnote 6 Table 4 presents our main results. Column (1) presents the results using the entire estimation sample while columns (2) and (3) present the results for sons and daughters separately. Columns (4) and (5) replicate columns (2) and (3) using standardised measures of gender-stereotypical education choice implying that the estimated coefficients can be interpreted as intergenerational correlations.Footnote 7,Footnote 8

Not surprisingly, daughters are more likely to enter female-dominated fields of study than sons. Conditioning on the full set of controls, daughters select into fields with a 27-percentage points greater share of female graduates in the year of enrolment. This coefficient is very similar to that found by Ancetol and Cobb-Clark (2013), who include measures on self-reported psychosocial characteristics to estimate a gender gap of 22 percentage points. This difference in preferences is driven neither by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics nor by human capital as captured by high school GPA. Although we cannot rule out discrimination before education completion, it seems likely that this gender segregation at least in part reflects different preferences for educational (and later occupational) characteristics. As expected, the coefficient on high school GPA in Table 4 is negative meaning that higher-ability individuals sort into less female-dominated fields, although this is most pronounced for daughters.

Standardisation matters little for the results and overall Table 4 establishes statistically significant and positive intergenerational correlations in female-dominated choice of education, although the same-sex parent correlations dominate. Roughly speaking, a 10-percentage point increase in share of females in father’s (mother’s) education is associated with a 0.8 (0.5) percentage points increase in the share of females in the son’s (daughter’s) education. Correspondingly, a one standard deviation increase in share of females in father’s (mother’s) education is associated with a 0.09 (0.05) standard deviation increase in the share of females in son’s (daughter’s) education. Also for daughters, there is a significant and positive correlation with share of females in father’s education, although, it is only one-third the size of the correlation with the share of females in mother’s education.Footnote 9 The weaker father-daughter correlations compared to the father-son correlations are in line with the existing literature on intergenerational correlations in earnings; see Black and Devereux (2011).

One might hypothesise that the correlations in gender compositions are particularly strong in the tails due to stronger transmission of gender stereotypes, i.e. for fathers and mothers who have chosen an education that is either very gender-stereotypical or not at all. Our findings suggest that same-sex correlations are largest when fathers and mothers have a very male-dominated education, see Appendix Fig. 4. Thus, the mother-daughter (father-son) correlation is higher when mothers (fathers) are untraditional (traditional). For the father-son correlation the pattern is less clear than for the mother-daughter correlation. From the perspective of closing the gender gap in gender-stereotypical education choice, we can think of traditional fathers as ‘bad apples’ and non-traditional mothers as ‘shining lights’; see Hoxby and Weingarth (2005) for an extensive overview of models of peer effects.

The presence of gender-specific transfers across generations is interesting in the light of the recent findings of Grönqvist et al. (forthcoming), who demonstrate that for Swedish youths born around 1980 the cognitive and non-cognitive skill transmissions from mothers and fathers are equally strong for children of both sexes. Adding our insights, these results suggest that children inherit (acquire) skills from both parents while their labour market behaviour mainly reflects that of the same-sex parent. This is consistent with the evidence presented in Johnston et al. (2014) that both sons and daughters hold the gender attitudes of their mothers although these are reflected only in the labour market behaviour of the daughters.

Using administrative data for Denmark, Brenøe and Lundberg (forthcoming) study the importance of parental education for children’s educational achievement and labour market outcomes. They find strong same-sex relationships for educational attainment, but contrary to us, they find this relationship to be driven by the female dimension. Hederos (2017) finds stronger father-son correlations for gender-stereotypical occupation choice using Swedish administrative data. One way to think about these results is that both the present analysis and the analysis in Hederos (2017) focus on one particular aspect of educational choices meant to capture gender-stereotypical educational choices, whereas Brenøe and Lundberg (forthcoming) focus on composite outcomes. For example, this suggests that in the aggregate especially mother-daughter interaction matters for educational attainment whereas the father-son interaction matters especially for the gender-stereotypical aspect of education choice. The latter is in line with several studies in the field of developmental psychology that have found that fathers have a stronger focus on gender socialisation (McHale et al. 2003).Footnote 10

5.2 The gender gap in gender-stereotypical choice of education

Another relevant dimension of intergenerational transmission of gender-stereotypical education choice is how parents’ choices relate to the gender gap in gender-stereotypical education choices of children. In line with our ex ante hypotheses, the results in Table 4 suggest that the share of females in mother’s education is positively related to the gender gap, while the share of females in father’s education is negatively related to the gender gap. Focusing on the gender gap, we can improve on the estimates in Table 4 by using within-family variation in sibling sex composition to reduce the influence from family-specific confounding factors in the transfer of educational preferences. In the spirit of Autor et al. (2017), we estimate the intergenerational transmission of female-dominated education choice for sisters relative to brothers within families.

Consider the following model,

for child i in family j. The parameters β4 and β5 represent the relationships between the daughter-son gender gap in gender-stereotypical education choice and the share of females in mother’s education and share of females in father’s education, respectively.Footnote 11

Table 5 presents the estimation results based on estimating Eq. (2) by OLS (column (1)) and family fixed effects (column (2)) using a subsample of matched siblings. Adding family fixed effects has little impact on the results. Due to little variance in highest obtained education of parents across siblings, one should not pay too much attention to the estimated level correlation coefficients.

A higher share of females in mother’s (father’s) education is positively (negatively) related to the share of females in daughter’s education relative to son’s education. In other words, the gender gap in children’s gender-stereotypical education choices is wider for children of parents who exhibit more gender-stereotypical behaviour—even when constant additive family effects are netted out. This is consistent with our findings in Table 4.

5.3 ‘A man should earn more than his wife’—the importance of fathers’ and mothers’ relative earnings

In order to dig deeper into the intergenerational transmission mechanisms of gender attitudes and assess the robustness of the results to the chosen registry measure of gender attitudes, we use our rich administrative register data sources to mimic a commonly used survey question on gender norms. Many empirical studies on gender attitudes are based on a survey question where respondents are asked to evaluate whether they agree with the statement ‘A man should earn more than his wife’. The administrative registers allow us to define a measure that captures whether an individual’s actual behaviour reflects this statement. We also construct a variable which indicates whether the parent earns more than ‘what might be expected, given his or her education and demographic group’; i.e. this measure is intended to capture (besides ‘luck’ and random shocks) unobserved ambitions and abilities of the parents; see Section 3.1.Footnote 12 Table 6 presents estimation results using these alternative measures of household gender attitudes.

Columns (1) and (4) of Table 6 present the point estimates of the mother’s share of household earnings in regressions of share of females in the education of sons and daughters, respectively, on all control variables in Table 3 and HHshareMom. Further, because the measures of gender attitudes now vary within educations, we include education fixed effects for both the mother and father (for both parents, we use about a hundred categories of type of education). This means that the correlations between the child’s gender-stereotypical education choice and the mother’s share of total household earnings is conditional on the type of both father’s and mother’s education. Thus, the correlations in Table 6 cannot be attributed to ‘pure’ educational choices alone making it more plausible that the observed correlations to some extent pick up gender norms and attitudes. In column (1), the coefficient on HHshareMomi is of the expected sign indicating that there is a positive relationship between the share of household earnings brought in by the mother and the share of females in son’s education. For daughters, the coefficient is also positive, contrary to a priori expectations, but not statistically significant (column (4)).

As discussed in Bertrand et al. (2015), gender identity in relative earnings is more plausibly related to the prescription ‘a husband should earn more than his wife’ rather than the actual earnings difference, although children in our setting may not observe the precise earnings difference. To address this issue, columns (2) and (5) substitute HHshareMom with an indicator for mothers earning more than fathers do (HHshareMom > 0.5). The coefficients on this indicator reflect our ex ante expectations for daughters. Being the daughter of a breadwinning mother is negatively associated with the share of females in the daughter’s education (daughters choices are less gender-stereotypical) while the association for sons is small and statistically insignificant.

Columns (3) and (6) in Appendix Table 14 explore the influence of HHshareMom across its distribution. The omitted category is mother’s share of household earnings between 40 and 50% encompassing the lion’s share of households; see Appendix Fig. 3. The results clearly show that for daughters the ‘traditional’ (in terms of most common: households with mothers earning between 30 and 60% of household earnings) households mainly drive the positive coefficient on HHshareMom. Consistent with our ex ante hypothesis that atypical contribution patterns to household earnings decrease the gender-stereotypical nature of education choice for sons, the positive coefficient for sons is driven by families with mothers earning a relatively larger fraction of household earnings: between 40 and 80% percent. However, for both daughters and sons, having either a breadwinning mother or father is generally associated with a less female-dominated choice of education (compared to the typical division), although for daughters ‘breadwinners’ should be defined more broadly.

Finally, we consider parental earnings gaps as measures of gender attitudes. A positive earnings gap indicates that the parent earns more than the potential (mean) earnings in his or her demographic group based on gender, field of study and age range, for example, because of higher career ambition or better skills. Note that this measure also picks up differential career ambitions that result in differences in occupational choice given their educational degree. If we use the interpretation proposed by Bertrand et al. (2015), a negative (positive) earnings gap for mothers (fathers) reflects gender-stereotypical labour market behaviour and, thus, we should expect negative coefficients of the same-sex parent’s variable and—possibly—positive coefficients for the opposite-sex parent. In Table 6, the coefficient on father’s earnings gap in column (3) is significantly negative for sons and the mother-daughter association in column (6) likewise, though slightly larger numerically. As expected, there is no significant relationship between mother’s earnings gap and son’s education choice, but daughters’ education choices appear to be related to their fathers’ earnings gap as well. Thus, even within father’s education, fathers earning 10% more than their potential earnings tend to have sons and daughters who obtain degrees in programmes with 0.06–0.08 standard deviations lower share of female graduates. Overall, this corroborates the results found in Section 5.1 that sons predominantly reflect paternal behaviour while daughters reflect the behaviour of both parents although more strongly the behaviour of the mother.

Finally, using the strategy outlined in Section 5.2, we estimate the relationship between these alternative measures of gender attitudes on the gender gap in gender-stereotypical education choice. Columns (7)–(9) in Table 6 present the results. Having a breadwinning mother has no statistically significant association with the gender gap, although the point estimates are negative as expected. Having parents who exceed their potential earnings is negatively associated with the gender gap in female-dominated education choice between sisters and brothers. In particular, the magnitude of the coefficients suggest that having a ‘career-minded’ mother reduces this gap by more than two times as much as a career-minded father if one were to interpret the estimates causally. In other words, having a mother that exhibits less gender-stereotypical labour market behaviour (although not in relation to her husband’s earnings) during adolescence is negatively associated with the gender gap in the choice of female-dominated education programmes of children.

In summary, conditional on a wide range of covariates, including parents’ type of education and individuals’ high school GPA, the more successful one’s parents are compared to their equals, the less female-dominated is the son’s or daughter’s choice of education. The more success in the educational system or in the labour market, the lower is the share of females in the education chosen by the individual, and sons predominantly reflect paternal behaviour while daughters are influenced by both parents although more strongly by the mother.

6 Exploring mechanisms

Having established the existence of (mainly same-sex) intergenerational correlations in measures of gender attitudes, it is a natural extension to seek to understand the mechanisms underlying these intergenerational correlations. We investigate four potentially important channels: intergenerational transfers of human capital, intra-family differences related to birth order and gender, family structure, and school and neighbourhood quality.

6.1 Human capital transfers

Acknowledging that the intergenerational correlations presented in Table 4 may reflect intergenerational transfers of general and specific human capital, we probe the importance of such transfers in the estimated intergenerational correlation by including different measures of human capital accumulation and excluding children who choose the same programme as one or both of their parents. Kirkeboen et al. (2016) find evidence that returns to education vary substantially across field of study. In addition, they find that these differential returns are consistent with individuals choosing a field where they have a comparative advantage. This highlights the importance of filtering any human capital transfer effects out of the estimated correlations.

In order to capture general human capital transfers, we include a control of high school GPA in our main specifications in Table 7. To the extent that children’s high school GPA captures such transfers, conditioning on GPA leads to an estimate of the intergenerational correlation net of these types of transfers. On the other hand, high school GPA is potentially affected by parental gender attitudes already, for example, a mother with traditional gender attitudes may raise her daughter to be less ambitious which may be reflected in a lower high school GPA. To inform us about the importance of general human capital transfers in terms of the estimated intergenerational correlations, columns (1) and (2) in Table 7 present the estimated intergenerational correlations for sons and daughters, respectively, when high school GPA is excluded from the conditioning set. In line with the hypothesis that general human capital transfers are important for education choices, the intergenerational same-sex correlations in female-dominated education choice are significantly higher when excluding high school GPA, although markedly more for daughters. The negative coefficients on GPA in Table 4 suggest that individuals who are more able graduate in less female-dominated fields. The coefficient is four times larger for daughters than for sons (albeit the difference is potentially caused by selection into the college estimation sample); thus, in particular high-ability daughters seem to endeavour to enter less female-dominated fields.

As an alternative approach to filter out human capital transfers, columns (3) and (4) in Table 7 present the estimated intergenerational correlations based on the subsample of children with a high school GPA above 10 (top 5% in the distribution). This subsample is of particular interest for two reasons. First, although human capital transfers may differ, human capital accumulation is similar for individuals in this subsample. Second, boys and girls in the top five percentiles are very similar in terms of background characteristics. The same-sex patterns of the highly selected group of students with a GPA in the top five percentile mirror the results of the full sample of college graduates, i.e. the correlations between mothers and daughters and fathers and sons are significantly positive albeit lower than in the full sample. Highly able daughters reflect the behaviour of their mothers and fathers equally.

In addition to general human capital transfers, transmissions of specific human capital may add to the intergenerational correlations in educational preferences. To render probable that transfers of programme-specific human capital and information are not driving our results, we estimate the model excluding children who graduate from the same or a similar programme as one or both of their parents (see columns (5) and (6) in Table 7).Footnote 13 The correlation coefficients decrease in magnitude but remain positive and statistically significant. We interpret this as evidence that transfers of education- or occupation-specific human capital drive a smaller part but not all of the same-sex correlations in female-dominated educational choice across generations.

In summary, Tables 4 and 7 present evidence that sons and daughters mirror the gender-stereotypical education choice of particularly their same-sex parent. More able women are less likely to choose a female-dominated (gender-stereotypical) education and are less (more) influenced by their mother (father). Men, on the other hand, are much less sensitive to ability level and reflect the behaviour of their fathers only. We note that although the estimated correlations are significant and positive, the correlation sizes are modest and especially for daughters, the explanatory power of female-dominated education choice for parents is small compared to, for example, high school GPA. Overall, the results are in line with our ex ante expectations that intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical education choice to some extent pick up transfers of general and specific human capital. In comparison, Hederos (2017) presents correlation estimates from specifications excluding observations where children to a varying degree have the same occupation as one of their parents for Swedish cohorts born in 1943–1952 and finds results that are consistent with ours.

6.2 Intensity of contact: birth order and sibling sex composition

One of the ways in which parents can transfer gender attitudes to their children is by spending time with their children. However, the intensity of contact between parents and children varies substantially. In this section, we use information on birth order and sibling sex composition to proxy for intensity of parent-child contact. Relatedly, in Section 6.3, we investigate the role that family structure plays in determining the intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical education choice. If more intense parent-child contact increases the estimated correlations, it is indicative evidence that acquired norms from parents during childhood take part in determining the educational choices of the children. In other words, if transmissions from a parent—other than inherited endowments—are important in shaping the educational preferences of children, we would expect that the intergenerational correlations in educational characteristics are increasing with the intensity of parental presence and time allocation during childhood.

A firstborn child (multiple borns excluded) will necessarily have enjoyed a period of “undivided” attention from its parents, and so we might expect that the associations are stronger for firstborns if the parental transmissions captured by gender-stereotypical education choice indeed contribute to forming children’s educational preferences. Relatedly, there is evidence that parents generally invest more in their firstborns (e.g. Averett et al. 2011; Lehmann et al. 2016).

To quantify the influence of birth order on the parental transmissions for children’s educational choice, we adjust the model in Eq. (2) to estimate the following reduced form model (separately for sons and daughters):

where β4 and β5 depict the differential responsiveness of firstborns compared to later-borns of the same sex to transfers from their mothers and fathers, respectively. For example, when estimating Eq. (3) for women, β4 denotes the differential influence of mother’s transmissions on daughters born as the first child compared to daughters born as the second or third child. We further augment Eq. (3) to include family fixed effects, thus, comparing daughters within families.

Columns (1) and (5) in Table 8 present the intergenerational correlation coefficients by birth order as estimated by Eq. (3) for sons and daughters from families with two or more children (all children need not be in the estimation sample), respectively. Overall, we find intergenerational correlations in these samples that are very similar to the baseline in Table 4.

In line with the predictions of increased parental investments in firstborns and our previous documentation of a negative relationship between ability and female-dominated education choice, firstborns generally graduate in less female-dominated fields. Importantly, though, the intergenerational correlation in female-dominated education choice is higher in the same-sex dimension only, i.e. mother-firstborn daughter and father-firstborn son. The mother’s (father’s) educational choice on average influences daughters (sons) who are firstborns relatively more than daughters (sons) who are born second or later.

In an attempt to address family-specific factors that directly affect children’s latent outcomes, for example shared genetics, columns (3) and (7) consider the differential responsiveness by birth order to parental transmissions within families while columns (2) and (6) simply report the corresponding OLS estimates. The coefficients on the share of females in parents’ education are identified only by variation in these measures between siblings at age 15. Because there is little variation in attained parental education between adolescent siblings, these are both imprecisely determined and difficult to interpret. The coefficients on the interaction terms are, however, determined as the differential influence of, e.g. mother’s educational characteristics on firstborns relative to later-born siblings of the same sex. Here, the father’s differential influence on firstborn sons relative to later-born sons disappears, although estimating Eq. (3) on the subsample of matched brothers suggests that the decrease is driven by selection into this sample (column (2)). The point estimate of the differential influence of mothers’ education on firstborn daughters roughly doubles. For completeness, columns (4) and (8) include an indicator for being the firstborn of your sex instead of being firstborn among both sexes. This yields very similar results. We find evidence that in particular mothers’ educational preferences are transmitted to the firstborn daughters.Footnote 14

By using information on birth order, we have—at least to some extent—eliminated inherited transfers as a confounding factor in our estimates of the intergenerational correlation. The observed difference in intergenerational correlations by birth order suggests that alternative mechanisms are at play. Furthermore, the intergenerational correlations are higher for firstborns (or the first child of either sex). These results are consistent with, for example, younger sisters identifying with older sisters rather than their mother, which would lower the extent of maternal influence on later-borns. Alternatively, maternal investments may be particularly strong for their firstborn daughters.

Sibling sex composition has been associated with parental educational investments of particularly daughters. For example, Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik (2016) propose that in the absence of a son, fathers may choose to invest in (one of) their daughters; that the presence of siblings of the opposite sex may reinforce gender roles (alternatively, reduce these if siblings mirror each other); or lastly, assuming that paternal investments are rival goods, that daughters being more adverse to competition are discouraged from paternal investments in the presence of sons. Empirically, Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik (2016) demonstrate that having a brother significantly lowers the probability of women choosing STEM majors when the father is in a STEM occupation relative to when he is not.

We hypothesise that transfers of parental norms and attitudes are rival goods to a much lower extent than for example skill transfers, as norms and attitudes may be transferred without one-to-one parent-child interactions. In addition, sibling peer effects may play a role as, for example, having an older sister may weaken the transfer of norms and attitudes from the mother not because the older sister is competing for maternal resources, but because the older sister herself transfers norms and attitudes to the younger sister. Auxiliary analyses presented in Appendix Table 15 suggest that same-sex sibling rivalry is not an important factor in our estimated intergenerational correlations. Having any brother(s) (sisters) does not significantly affect the intergenerational correlations in female-dominated education for sons (daughters) compared to when only opposite-sex children are in the family. In accordance with the birth order correlations presented in Table 8, the presence of older same-sex sibling(s) decreases the same-sex intergenerational correlations in female-dominated education choice. Combining this with the findings of Joensen and Nielsen (forthcoming) who find positive spillovers from older siblings to younger siblings in terms of course choices in high school suggests that older same-sex siblings weaken the transmission from same-sex parents, for example by posing as rival role models. We find marginal evidence that the presence of a sister decreases the intergenerational transmission from mothers to sons, which is consistent with mothers preferring daughters to sons. However, unlike Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik (2016), we do not find evidence that the presence of sons lowers the educational transmission from fathers to daughters.Footnote 15

6.3 Intensity of contact: family structure

We now use information on family structure as a proxy for the intensity of parent-child contact during childhood. Information on where the child lives if parents are divorced along with information on new spouses are available in detail from 1990 and onwards, thus family structure is measured at age 15 for cohorts born in 1975–1986. Columns (1)–(5) and columns (6)–(10) in Table 9 present the results for sons and daughters, respectively.Footnote 16 Columns (1) and (6) present the correlation coefficients for individuals living with both parents at age 15, comprising the majority of the sample. These correlations are very similar to the baseline in Table 4. The correlation coefficients remain roughly the same for children living only with their same-sex parent or their same-sex parent and a new partner (columns (4)–(5) for sons and (7)–(8) for daughters).Footnote 17 Interestingly, when sons live with their mothers alone, the coefficient on the share of females in their mothers’ education increases and becomes marginally significant. The influence of the father remains unchanged (column (2)). When the mother finds a new partner (column (3)), her influence disappears and the father’s decrease as well, though the correlation with the education choice of the new spouse is not significant. Although less convincing due to severely limited sample sizes, the intergenerational correlations for daughters living with their fathers exhibit the same pattern, although when the father finds a new partner the correlations become pretty high and very imprecise.

These differential patterns are in line with our expectations if parental transmissions during childhood indeed affect educational preferences. In the absence of the same-sex parent, the opposite-sex correlations increase. The pattern blurs somewhat when the parent finds a new partner; for sons, the influence of both parents is reduced, for daughters, it is larger in magnitude but insignificant. However, it is important to stress that child custody decisions are not random as further indicated by the large discrepancies in the numbers of children living with their mother versus father in case of a divorce (see also Appendix Table 17). One may therefore easily construct selection-based explanations with the same hypothesised outcomes; for example, families in which fathers gain physical custody of the children probably have untraditional family norms.

6.4 The influence of peers: schools and neighbourhoods

While parents with particular gender attitudes may directly transfer these attitudes to their children, they also make choices on behalf of their children that maybe related to their gender-stereotypical education choice or their gender attitudes more generally. Some of the important choices made by parents are to select a place of residence and a school for the child to attend. Both high-quality neighbourhoods and high-quality schools have been shown to have favourable effects on children’s outcomes; see Chetty et al. (2016), Autor et al. (2016) and (2017). Autor et al. (2016) find that school quality is important for student performance and particularly that school quality decreases the gender gap in academic performance.

The estimated intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical choice of education in Table 4 may also reflect differential behaviour in terms of choice of neighbourhood and school on the part of parents with differing gender attitudes. To the extent that this behaviour is constant within families, the results in Table 5 do not reflect parents’ choice of neighbourhood and school. The baseline specifications in Table 4 include indicators for residential municipality, which pick up neighbourhood peers to the extent that this can be captured with a fixed effect. However, excluding these municipality indicators has little impact on the results. Since municipalities are arguably relatively large geographic units, we investigate the potential importance of peers further by including school (the school attended in grade 9) fixed effects and subsequently school by cohort fixed effects in the original specification, see Appendix Table 18. The former is thought to predominantly pick up localised neighbourhood effects, while the latter to a larger extent will net out school quality and peer composition. Again, the estimated intergenerational correlations change very little. Since the majority of Danes attend the local neighbourhood school, inclusion of school fixed effects to some extent also controls for neighbourhood. The results are remarkably similar and suggest that selection into specific schools is not driving the observed correlations.Footnote 18

Consistent with our ex ante hypothesis of gender identity transmissions, the share of females in mother’s education is positively related to the share of females in daughter’s education. This is significantly more so than for sons, and vice versa for the father-children relationships. While this evidence is not entirely conclusive, our analyses document a persistent pattern in education choice across generations that is not only explained by individuals opting for the same education as their parents. Our explorations in this section have largely supported our previous findings while uncovering some interesting channels within families and across sibling compositions, suggesting that transfers of human capital and intensity of contact are important factors in intergenerational transmission of gender-stereotypical choices.

7 Concluding remarks

Motivated by a number of recent papers that emphasise and document the role of gender-stereotypical preferences in explaining the remaining gender gaps in the labour market, we investigate the intergenerational correlation in gender-stereotypical education and labour market choices. We use the share of females in the chosen educational programme to measure children’s gender-stereotypical choices.

We find a positive and significant intergenerational correlation of the share of females in education choice. Specifically, we document significant same-sex correlations in the tendency to select into female-dominated educations across generations. Daughters’ education choices are more highly correlated with their mothers’ behaviour, while sons’ education choices are more highly correlated with their fathers’ behaviour. The mother-son and father-daughter correlations are generally smaller and in most cases insignificant. Interestingly, the father-son correlations seem strongest, less related to skill level and less sensitive across specifications. Additionally, sons are rarely influenced by the behaviour of the mother; however, this may in part reflect the lower wages in women’s fields. Overall, analyses based on alternative measures of parental gender attitudes using mother’s share of household earnings and parents’ potential earnings confirm this pattern. Interestingly, we find that the gender gap in children’s gender-stereotypical education choices is wider for children of parents who exhibit more gender-stereotypical behaviour—even when constant additive family effects are netted out.

Based on a range of analyses investigating potential mechanisms underlying the estimated intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical education choice, we conclude that particularly human capital transfers and intensity of contact (as proxied by birth order, sibling sex composition and family structure) are important contributing factors. Using information on birth order and sibling composition, we analyse in detail how these correlations differ with the intensity of the parent-child relationship. We find that the same-sex intergenerational correlations are generally higher for firstborns than for later-borns which may reflect differential resource allocation depending on birth order. Our results do not support the hypothesis that schools are important drivers of these intergenerational correlations.

Our results also indicate that conditional on a wide range of covariates including detailed controls for parents’ education, the more successful one’s parents are in the labour market compared to their equals, the less female-dominated is the choice of education of the children. Sons predominantly reflect fathers’ behaviour while daughters reflect the behaviour of both parents although more strongly by the mother. The estimated correlations can result from various transmission mechanisms. While we cannot definitively eliminate any of these channels, our results are consistent with intergenerational transmission of gender stereotypes resulting in sticky gender norms. Specifically, the symmetry of father-son and mother-daughter correlations (and the absence of corresponding opposite-sex correlations) suggests the presence of gender-specific transfers within families. In comparison, Grönqvist et al. (forthcoming) find that the cognitive and non-cognitive skill transmissions from mothers and fathers are equally strong for children of both sexes. Taken together, these results suggest that children inherit skills from both parents while their labour market behaviour mainly reflects that of the same-sex parent.

The dominant same-sex correlations which have been found in different aspects of labour market and education choices (see also Brenøe and Lundberg forthcoming, and Hederos 2017) are likely to be an important part of the explanation of why gender gaps remain in labour markets. More research is needed to determine why these gender gaps remain even where women have been part of the labour force for decades and where they have outperformed their male peers with respect to quantity of education.

From the perspective of policy makers, the potential intergenerational transfers of gender attitudes pose a considerable challenge. If gender equality is an important policy perspective, a feasible policy would have to counterweigh the gender attitudes or gender-stereotypical information provided by parents. This is not an easy task for politicians. One potential instrument could be the kind of information conveyed by marketing and information campaigns of college programmes. However, an important question is whether the timing of alternative information on gender attitudes is important, and whether children’s gender attitudes are more malleable at early ages, i.e. already in compulsory school or earlier? Much further research is needed to answer these questions.

Notes

For example, physiotherapy has seen a marked increase in male graduates from the 1970s to the 2000s; however, with more than 70% female graduates on average in the 2000s it is still decidedly female. Fields such as nursing, teaching and humanities are still predominantly female, while engineering and business are distinctively male (Goldin 2014a). Pan (2015) documents that occupational segregation exhibits a “tipping” pattern, i.e. occupations rapidly become predominantly female once the share of females in an occupation exceeds a certain threshold and demonstrates that the threshold is lower when men hold more traditional gender attitudes.

Several papers study transmissions of self-reported gender roles or self-stereotyping using surveys and retrospective questionnaires (for example, Johnston et al. 2014). However, survey measures of self-reported gender roles and self-stereotyping may suffer from different types of measurement problems. In particular, the respondent may not answer truthfully if gender norms and identity are considered a controversial area (Eriksson et al. 2016). Therefore, the degree to which children would pick up or respond to these self-reported measures is uncertain.

Year of enrolment and graduation is incomplete before 1971; thus, we match the share of female graduates in the year the parent turns 30 to the highest attained education for parents when their son or daughter is 15 years old.

Although, parental characteristics at age 15 may in part reflect behavioural response to the child itself, for our purpose, we prefer to use the later measures to capture the household norms at the age when the child faces the first actual educational choices and already has developed an autonomous ‘persona’ presumably reflected in the parents’ behaviour. For example, Burt and Scott (2002) confirm that gender role attitudes extend back into early adolescence. Furthermore, using age 15 instead of a younger age (e.g. age 5) allows us to obtain a larger sample. Sensitivity checks using variables measured at age 5 (i.e. cohorts born in 1975–1986) yield very similar results, see Appendix Table 11. We attribute the stability in the intergenerational correlations in gender-stereotypical choice of education across different ages of assignment to be a result of the fact that for the vast majority of parents the education choice is made prior to birth of their children.

The older high school registers are limited to two types of general high schools (STX and HF), with single-course HF included from 1992 and technical (HTX) and business (HHX) high schools from 2001 onwards. Further, only passed GPAs (above 5.5, equivalent to D by US standards) are recorded. Overall, high school GPA is therefore missing for a relatively large fraction of individuals (15%). Where information on non-primary individual controls is missing, a dummy variable adjustment approach is used.

The estimated intergenerational correlations reflect correlations between parents and children. Adermon et al. (2016) find that considering a horizontally extended parent generation leads to intergenerational correlations in education that are almost twice as large as the conventional estimates suggesting that intergenerational transfers from the extended family are also very important in determining children’s education choices.

See Appendix Table 10 for the full regression output for columns (4) and (5).

We do not include fixed effects for parental field of study in our regressions with the shares of female graduates in parents’ education as the primary regressors. Were we to condition on parental educational field, the intergenerational correlations would be identified only by the variation in the share of females to obtain a certain degree over time, which is undesirable if educational gender stereotypes are sticky. Including fixed effects for 11 broad educational fields does not change our findings, although it to some extent affects the magnitude of the correlation coefficients.

In a number of auxiliary estimations, we have tested alternative models and used different subsamples of children. Instead of children completing a BA degree using the completed type of education as the measure of educational choice, we have used the sample of children who enrolled at a BA as a first choice of education. First choices might reflect gender attitudes more accurately than completed education, which is further influenced by cognitive and non-cognitive skills. These results do not deviate notably from the results in Table 4, see Appendix Table 11.

Relatedly, Johnston et al. (2014) present mother-daughter correlations in gender role attitudes of 0.09 SD. The mother-son correlations are similar though labour market outcomes for sons appear unaffected, and gender role attitudes are only measured for mothers.

Given the gender attitudes of parents, they may value sons and daughters differently, which may lead to differences in latent potential outcomes between these children. Autor et al. (2017) argue that gaps in neonatal health may act as proxies for the gaps in latent outcomes between children. For example, Black et al. (2007) and Lesner (forthcoming) show that birthweight is a strong predictor for later labour-market outcomes. Appendix Table 12 demonstrates that the gender gap in birthweight is insignificantly related to our measures of parents’ gender-stereotypical education choice and labour market behaviour, suggesting that differential in utero investments by gender are unrelated to parents’ stereotypical education choice. The differential pattern between sexes is therefore likely to arise from post-natal influences, for example, differential sensitivity of boys compared to girls to transmissions from mothers and fathers and/or differential parental investments in boys versus girls. Still, this analysis has not addressed that neighbourhoods and school environments may vary with parental gender attitudes.

Inspired by Fernández and Fogli (2009) and Blau et al. (2013), we also attempt to capture parental gender norms by using information on the source country of second-generation immigrants. Contrary to Fernández and Fogli (2009) and Blau et al. (2013), we do not find significant and robust correlations in cultural proxies once controlling for cognitive skills, see Appendix Table 13.

The same or similar programme is defined based on the first six digits of the eight digit EKFSP-codes identifying educational programs. For example, all archaeology programmes (classical, prehistoric, medieval etc.) are bundled together in ‘Archaeology’, whereas physics, biophysics, geophysics, and technical physics are bundled as ‘Physics’.

The relationship between the birth-order gap in birthweight and the measures of parents’ gender-stereotypical education choice and labour market behaviour is statistically insignificant suggesting that differential in utero investments across birth order or sex is unrelated to parents’ stereotypical education choice, see Appendix Table 12 and footnote 11 for further discussion.

Differential fertility patterns for parents on the range of female-dominated education programmes potentially explain these results. For example, differences in father-daughter transmissions when a brother is present, compared to when not, are attenuated if fathers with traditional gender norms are more likely to continue having children until they father a boy. Supplementary analyses on fathers in the estimation sample suggest some indication that fathers with more gender-stereotypical education choices have a preference for sons, see Appendix Table 16.

Table 17 in the Appendix shows the corresponding selection equations estimated by linear probability models where the dependent variable is an indicator for a particular family structure. In lack of better predetermined measures, we include share of females in parents’ education, parents’ education level and number of siblings measured at age 5. These results suggest that having parents with vocational or higher education tends to be negatively associated with breakup with the main exception that having a father with a higher education increases the probability of the child living with the father and a new partner. Interestingly, having parents that exhibit less gender-stereotypical behaviour tends to be associated with a higher risk of parental breakup.

Individuals living with their mother because their father died and vice versa are excluded from the samples. Due to small sample sizes, estimations on subsamples in which parents have died from external causes do not add much information to our analysis and are therefore omitted here.

Unfortunately, we do not have information about school level characteristics such as gender composition of classrooms or pedagogical body.

References

Adermon A, Lindahl M and Palme M (2016) Dynastic human capital, inequality and intergenerational mobility. IFAU Working Paper 2016:19

Alesina A, Giuliano P, Nunn N (2013) On the origins of gender roles: women and the plough. Q J Econ 128(2):469–530

Ancetol H, Cobb-Clark D (2013) Do psychosocial traits help explain gender segregation in young people’s occupation? Labour Econ 21:59–73

Autor D, Figlio D, Karbownik K, Roth J and Wasserman M (2016) School quality and the gender gap in educational achievement. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 2016 106(5):289–295

Autor D, Figlio D, Karbownik K, Roth J and Wasserman M (2017) Family disadvantage and the gender gap in behavioral and educational outcomes. NBER Working Paper Series, 22267

Averett S, Argys L, Rees D (2011) Older siblings and adolescent risky behavior: does parenting play a role? J Popul Econ 24(3):957–978

Bertrand M, Kamenica E, Pan J (2015) Gender identity and relative income within households. Q J Econ 130(2):571–614

Björklund A and Salvanes KG (2011) Education and family background: mechanisms and policies. Chapter 3, In: EA Hanushek, S Machin and L Woessmann (eds) Handbook of the economics of education, vol 3, pp 201–247

Black SE and Devereux PJ (2011) Recent developments in intergenerational mobility, Chapter 16, In OC Ashenfelter, and OD Card (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 4b, pp 1487–1541

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2007) From the cradle to the labor market? The effect of birth weight on adult outcomes. Q J Econ 122(1):409–439

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2006) The U.S. gender pay gap in the 1990s: slowing convergence. Ind Labor Relat Rev 60(1):45–66

Blau FD, Kahn LM, Liu AY, Papps KL (2013) The transmission of women’s fertility, human capital and work orientation across immigrant generations. J Popul Econ 26:405–435

Bordalo P, Coffman K, Gennaioli N, Shleifer A (2016) Stereotypes. Q J Econ 131(4):1753–1794

Brenøe AA and Lundberg S (forthcoming). Gender gaps in the effects of childhood family environment: do they persist into adulthood? Forthcoming in European Economic Review

Burt KB, Scott J (2002) Parent and adolescent gender role attitudes in 1990s Great Britain. Sex Roles 46(7):239–245

Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF (2016) The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am Econ Rev 106(4):855–902

Corak M, Piraino P (2011) The intergenerational transmission of employers. J Labor Econ 29(1):37–68

Dunn T, Holtz-Eakin D (2000) Financial capital, human capital and the transition to self-employment: evidence from intergenerational links. J Labor Econ 18(2):287–305

Eriksson T, Smith N and Smith V (2016) Gender stereotyping and self-stereotyping attitudes among managers. Prevalence and consequences. EALE 2016 Conference paper

Fernández R, Fogli A (2009) Culture: an empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. Am Econ J Macroecon 1(1):147–177

Fernández R, Fogli A, Olivetti C (2004) Mothers and sons: preference formation and female labor force dynamics. Q J Econ 119(4):1249–1299

Goldin C (2014a) A grand gender convergence: its last chapter. Am Econ Rev 104(4):1091–1119

Goldin C (2014b) A pollution theory of discrimination. Chapter 9. In: Platt Boustan L, Frydman C, Margo RA (eds) Human capital in history: the American record. University of Chicago Press, Chicago