Abstract

Purpose

Limited data exist on the correlation between higher flow rates of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) and its physiologic effects in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF). We assessed the effects of HFNC delivered at increasing flow rate on inspiratory effort, work of breathing, minute ventilation, lung volumes, dynamic compliance and oxygenation in AHRF patients.

Methods

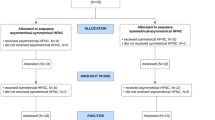

A prospective randomized cross-over study was performed in non-intubated patients with patients AHRF and a PaO2/FiO2 (arterial partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen) ratio of ≤300 mmHg. A standard non-occlusive facial mask and HFNC at different flow rates (30, 45 and 60 l/min) were randomly applied, while maintaining constant FiO2 (20 min/step). At the end of each phase, we measured arterial blood gases, inspiratory effort, based on swings in esophageal pressure (ΔPes) and on the esophageal pressure–time product (PTPPes), and lung volume, by electrical impedance tomography.

Results

Seventeen patients with AHRF were enrolled in the study. At increasing flow rate, HFNC reduced ΔPes (p < 0.001) and PTPPes (p < 0.001), while end-expiratory lung volume (ΔEELV), tidal volume to ΔPes ratio (V T/ΔPes, which corresponds to dynamic lung compliance) and oxygenation improved (p < 0.01 for all factors). Higher HFNC flow rate also progressively reduced minute ventilation (p < 0.05) without any change in arterial CO2 tension (p = 0.909). The decrease in ΔPes, PTPPes and minute ventilation at increasing flow rates was better described by exponential fitting, while ΔEELV, V T/ΔPes and oxygenation improved linearly.

Conclusions

In this cohort of patients with AHRF, an increasing HFNC flow rate progressively decreased inspiratory effort and improved lung aeration, dynamic compliance and oxygenation. Most of the effect on inspiratory workload and CO2 clearance was already obtained at the lowest flow rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent studies have reported that in non-intubated adult patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (AHRF), high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) improves oxygenation, lowers the respiratory drive, decreases desaturation during intubation and prevents re-intubation of high- and low-risk patients [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Preliminary data also suggest that HFNC may also decrease mortality [4]. The physiologic mechanisms of HFNC that potentially underlie its clinical benefits may include reduced inspiratory effort and work of breathing, improved lung mechanics, increased end-expiratory lung volumes, likely due to the positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) effect, lower minute ventilation [8], higher alveolar fraction of inspired oxygen FiO2) [9, 10], increased carbon dioxide (CO2) clearance by washout of anatomic dead space [11, 12] and more efficient removal of secretions [2, 9].

In all these clinical and physiologic studies, the set HFNC flow rates were extremely heterogeneous, ranging between 15 and 100 l/min [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] and, to our knowledge, no study systematically compared different flow rates in AHRF patients. Thus, when caring for a AHRF patient, a key question remains open: what is the best flow rate during HFNC treatment?

Data from healthy adults and cardiac surgery and tracheotomized patients weaned from mechanical ventilation (i.e. in the non-acute phase) suggest that the increase in pharyngeal pressure (i.e. the PEEP effect) and the decrease of the respiratory rate induced by HFNC are correlated with the set flow rate [13,14,15,16,17,18]. These effects were enhanced by asking subjects to keep their mouth closed during breathing on HFNC, but this is not feasible in the real-life, long-term treatment of AHRF patients [13, 14, 18]. Moreover, theoretically, the application of HFNC at higher flow rates should exploit other physiologic benefits in AHRF patients (e.g. improved oxygenation by progressive reduction in the difference between the set and the alveolar FiO2).

To address the question mentioned above on the best flow rate during HFNC treatment, we performed a physiologic randomized cross-over study aimed at measuring the following physiologic effects of HFNC at increasing flow rates in AHRF patients: oxygenation and gas exchange; respiratory rate, minute ventilation, lung mechanics, end-expiratory lung volume (EELV), effort. To increase the clinical impact and reproducibility of the data, patients did not receive any instruction regarding mouth opening/closing during any phase of the study. The aims of this study were: (1) to describe whether the physiologic effects of HFNC improve by increasing flow rate; (2) to assess the best model (i.e. linear vs. quadratic vs. exponential) to describe the correlation between each target physiologic variable and HFNC flow rate; (3) to describe the optimum flow rate for each target physiologic variable, defined as the one obtaining maximum optimization in most patients.

Methods

Study population

We enrolled 17 non-intubated AHRF patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy. Inclusion criteria were: new or worsening respiratory symptoms (e.g. dyspnea, shortness of breathing) following a known clinical insult (e.g. pneumonia) lasting <1 week; PaO2 (arterial partial pressure of oxygen)/FiO2 of ≤300 while receiving additional oxygen as per clinical decision; evidence of pulmonary infiltrates on chest X-ray performed on the day of the study. Exclusion criteria were: age <18 years; presence of tracheostomy; hemodynamic instability (hypotension with mean arterial pressure of <60 mmHg despite volume loads or vasoactive drugs); evidence of pneumothorax on chest X-ray or computed tomography scan; respiratory failure explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload; severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; history of nasal trauma and/or deviated nasal septum; altered mental status; contra-indication to electrical impedance tomography (EIT) (e.g. patient with implantable defibrillator); impossibility to position the EIT belt (e.g. wound dressings or chest drains); impossibility to position the esophageal pressure (Pes) catheter (e.g. esophageal surgery). The Ethical Committee of the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy approved the study (reference number: 1628/2015), and informed consent was obtained from each patient according to local regulations.

Demographic data collection

At enrolment, the following variables were collected: sex, age, predicted body weight, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II at ICU admission, Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, days since recognition of AHRF by ICU physician, etiology of the AHRF, PaO2/FiO2 by arterial blood gas analysis and presence of bilateral infiltrates on chest X-ray (both performed for clinical reasons the same day of the study).

Esophageal pressure and EIT monitoring

A nasogastric tube equipped with an esophageal balloon (Nutrivent Sidam, Mirandola, MO, Italy) was advanced through the nose for 50–55 cm to reach the stomach and inflated by the recommended volume (4 ml). The intra-gastric position was confirmed by the positive pressure deflections during spontaneous inspiration. The catheter was then withdrawn into the esophagus, as indicated by the appearance of cardiac artifacts and negative swings of pressure tracings during inspiration, and fixed [19,20,21]. The accuracy of esophageal pressure measurements relies on standardized careful positioning and on the visual inspection of tracings, as calibration against airway pressure swings during occlusion is technically challenging in non-intubated patients. Waveforms of the esophageal pressure were recorded for 5 min at the end of each study phase and before starting the next one by a dedicated data acquisition system (Colligo Elekton, Milan, Italy). An EIT dedicated belt containing 16 equally spaced electrodes was placed around each patient’s thorax at the fifth or sixth intercostal space and connected to a commercial EIT monitor (PulmoVista® 500; Dräger Medical GmbH, Lübeck, Germany). During the study, EIT data were generated by applying small alternate electrical currents rotating around the patient’s thorax at 20 Hz, so that tomographic data were acquired every 50 ms throughout all study phases and stored for offline analyses performed by dedicated software (Dräger EIT Data Analysis Tool and EITdiag; Dräger Medical GmbH) [22]. The esophageal pressure and EIT signals were synchronized offline with specific markers indicating relevant time-points created online during each study phase.

In three patients, esophageal pressure monitoring could not be obtained for technical reasons (e.g. poor quality of the recorded tracings or technology failure).

Calibration of EIT

After starting the EIT recordings and before beginning the study protocol, we recorded spirometry through a spirometer connected to a mouthpiece with occluded nostrils during spontaneous breathing for 30 s for offline calibration of the EIT measures. Briefly, 3–5 representative tidal volumes were selected on spirometry and EIT tracings, and the average ratio between milliliters and arbitrary units of impedance change was calculated and used to transform impedance changes into lung volume variations during all study phases. After the calibration phase, the mouthpiece and spirometer were removed, and the patients could breathe freely. EIT calibration was not repeated after the start of the first study phase as this step would have altered the physiologic breathing pattern and prolonged duration of an already long study (>1.5 h).

Study protocol

Patients were kept in semi-recumbent position without sedation. A calm environment was ensured around the patients throughout the study. Each patient underwent four study phases in computer-generated random order, with each phase lasting 20 min:

-

1.

Standard non-occlusive oxygen facial mask with gas flow set at 12 l/min;

-

2.

HFNC with gas flow at 30 l/min;

-

3.

HFNC with gas flow at 45 l/min;

-

4.

HFNC with gas flow at 60 l/min.

HFNC was delivered through specific nasal prongs of medium or large size (Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand) to fit the size of the nares. The set FiO2 was clinically chosen by the attending physician before patient enrolment to target a peripheral saturation of 90–96% on pulse oximetry during standard oxygen facial mask breathing and was kept constant during all phases. The set FiO2 during each phase was measured using a dedicated system (AIRVO™ 2; Fisher and Paykel Healthcare) connected to the standard facial mask or the HFNC. The system can deliver air flows of between 2 and 60 l/min with a set FiO2 (continuously measured at the gas outlet of the system) of between 0.21 and 1.0 by connection to a wall oxygen supply. During all phases, we reached the same measured set FiO2 by increasing or decreasing the additional oxygen wall supply in increments. Patients did not receive any instruction regarding mouth opening or closing during any study phase (i.e., during data collection the patients could breathe with the mouth open, closed or alternating both).

At the end of each study phase, we collected data on the arterial blood gas analysis, respiratory rate and hemodynamics.

Esophageal pressure data

From the esophageal pressure waveforms analyzed offline we measured:

-

1.

The average pressure time product of esophageal pressure over a minute (PTPPes), defined as the sum of the areas subtended by the esophageal pressure waveform during inspiration over a period of 2–3 min divided by the number of minutes, as a measure of patient’s effort over 1 min [21, 23]. PTPPes represents a modification of the classic computation of the pressure–time product that requires measurement of the passive elastic recoil of the chest wall. However, chest wall elastance cannot be measured in non-intubated patients and the addition of passive elastic recoil of the chest wall to PTPPes in the four study phases would not modify our results as tidal volume did not change (see below) and lung elastance would be assumed to be equal.

-

2.

The average esophageal pressure swings during inspiration (ΔPes), defined as the difference between end-expiratory and end-inspiratory esophageal pressure in the same series of representative breaths used to measure PTPPes, divided by the number of breaths, as a measurement of the patient’s inspiratory effort [21, 23].

EIT data

The raw EIT data recorded during the esophageal pressure recordings were analyzed offline. We divided the EIT lung-imaging field into two regions of interest: from halfway down we identified the dependent dorsal lung region, while the other half represented the non-dependent ventral region. We measured the following EIT parameters:

-

1.

The average global tidal volume as well as those distending non-dependent and dependent lung regions in a series of representative breaths, divided by the number of breaths (V T, glob, V T, non-dep and V T, dep, respectively);

-

2.

The minute ventilation (MV), measured as the sum of all tidal volumes over two to three representative minutes divided by the number of minutes, which may represent a more precise measure of MV than multiplication of average tidal volume by average respiratory rate (RR);

-

3.

Corrected minute ventilation (MVcorr), defined as MV multiplied by the ratio of the patient’s PaCO2 (partial pressure CO2/40 mmHg (i.e. MVcorr = MV × [actual PaCO2/40 mmHg]) [24], with lower values indicating enhanced CO2 clearance, less CO2 production or both;

-

4.

Global and regional changes in lung aeration during the HFNC phase (ΔEELVglob, ΔEEL × Vnon-dep and ΔEELVdep), as previously described [22]. Briefly, considering the facial mask phase as baseline, we measured global and regional changes in end-expiratory lung impedance expressed as arbitrary units (a.u.) during HFNC phases and multiplied these by the calibrating ml/a.u. factor.

Finally, esophageal pressure and EIT data were combined and used to calculate the dynamic compliance of the lung as V T, glob/ΔPes, to evaluate the effects of HFNC on lung mechanics.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was based on previous studies [8, 13,14,15,16,17,18, 21,22,23]. Normally distributed variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), while median and interquartile range were used to report non-normally distributed variables. Differences between variables across different HFNC flow rates obtained during each study phase were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures or by one-way repeated measures ANOVA on ranks, as appropriate. Post hoc correction for multiple comparisons was performed using Bonferroni comparison. To assess the best fitting model describing the relative improvement of each variable at increasing flow rates and considering the facial mask as baseline, we applied three different statistical models to the variations between phases: linear, quadratic and exponential. We then estimated the accuracy of each model for every variable by the Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) value, corrected for finite sample size (AICc). The AIC is a statistical technique introduced to help identify the optimal representation of explanatory variables collected with an adequate number of parameters. AICc introduces an extra correction term to overcome the problem of overestimating the order of the model in the case of small sample size. The individual AICc values are not easily interpretable so they are usually compared to the minimum AICc evaluated for the bulk of data collected. The model with the smallest value of AICc is considered the best model. Finally, the flow rate which obtained the highest change from the facial mask phase of each parameter in most patients was indicated as the optimum flow. A level of p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA) and JMP PRO 12 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient population

The patient population consisted of 17 patients, nine (53%) of whom were women, with a mean age (±SD) of 62 ± 10 years. Severity of clinical condition was relevant, as indicated by SAPS II at ICU admission of 48 ± 13 and SOFA score of 11 ± 3. Eight patients (47%) had pulmonary etiology of AHRF and nine (53%) presented a non-infectious cause. The number of days since recognition of AHRF in the ICU were 2 ± 1 (range 1–3). Twelve patients (70%) presented bilateral infiltrates on chest X-ray. The patients’ characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Best model for the correlation between physiology and HFNC flow rates

The AICc analysis indicated that linear correlation better described variations of ΔEELVglob and ΔEELVdep, V T/ΔPes, RR and PaO2/FiO2 with increasing HFNC flow rates [Table 2; Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Table E1, Figs. E1A, E1B). On the other hand, exponential fitting better matched the decrease of ΔPes, PTPPes, MV and MVcorr at higher flow (Tables 1, 2; ESM Figs. E2A, E2B), possibly indicating that most of the effects of HFNC on effort and CO2 wash-out/production were already obtained at 30 l/min. However, we must acknowledge that differences in AICc were relatively small for some variables (e.g. ΔPes).

Optimum flow rate during HFNC treatment

Optimum flow, defined as the HFNC flow rate obtaining maximum optimization of each physiologic parameter (i.e. absolute reduction or increase from facial mask, as appropriate) in most patients, was 60 l/min for ΔPes, PTPPes, ΔEELVglob, ΔEELVdep, V T/ΔPes, RR and PaO2/FiO2; 45 l/min for none of the physiologic parameters and 30 l/min for MV and MVcorr (Table 3). However, we must note that the flow associated with the largest improvement showed significant variability between patients: for example, considering ΔEELVdep (optimum flow 60 l/min), in 37% of patients the highest increase was obtained at 30 or 45 l/min (ESM Table E2).

Patients’ drive and effort at increasing HFNC flow rates

Only the results of the fixed-effects ANOVA model are presented in this section; the actual values and flow-level post hoc analyses are reported in Table 4. Patients’ drive, as assessed by respiratory rate, progressively decreased (p < 0.01 by ANOVA) during HFNC in comparison to the facial mask. Similarly, the inspiratory effort as measured by ΔPes and PTPPes decreased significantly by application of HFNC at increasing flows (p < 0.001 for both) (Table 4; Fig. 1a; ESM Fig. E3).

Non-linear physiologic effects of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) delivered at increasing flow rates. a, b In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, HFNC delivered at increasing flow rate (30, 45 and 60 l/min) reduces the esophageal pressure–time product (PTP Pes ), which is a measure of patient effort (a) and corrected minute ventilation (MV), i.e. the MV needed to maintain a physiologic arterial carbon dioxide tension (MV corr ) (b) in an exponential decay manner in comparison to the standard facial mask. Filled circles represent individual patients' value at each flow rate while the horizontal line is the mean value. § indicates p <0.05 by post-hoc Bonferroni test vs. Facial mask

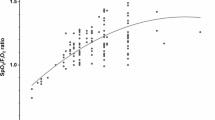

Lung volumes, mechanics and oxygenation at increasing HFNC flow rates

The results of the fixed-effects ANOVA model are reported in this section; actual values and flow-level post hoc analyses are reported in Table 4. Global and regional tidal volume did not change during HFNC in comparison to standard facial mask (Table 4). In contrast, EELV increased significantly during treatment with HFNC in comparison to facial mask, both globally and in the dependent lung region, indirectly suggesting PEEP effect and recruitment (p < 0.01 for both) (Table 4; Fig. 2a; ESM Fig. E3). EELVnon-dep remained stable in comparison to the facial mask, likely indicating minimal additional risk of lung hyperinflation. HFNC significantly reduced minute ventilation and corrected minute ventilation (p < 0.01 for both) in comparison to the facial mask, possibly indicating enhanced CO2 clearance from the nasopharyngeal dead space, decreased CO2 production, or both (Fig. 1b; Table 4). More favorable mechanical characteristics of the lung, as indicated by increased V T/ΔPes ratio, became evident during HFNC compared to standard facial mask (p < 0.01). Finally, PaO2/FiO2 increased at higher flow rates (p < 0.001; Fig. 2b), while PaCO2 and pH did not vary (Table 4).

Linear physiologic effects of HFNC delivered at increasing flow rates. a, b In acute hypoxemic respiratory failure patients, HFNC delivered at increasing flow rates of 30, 45 and 60 l/min induced significant changes in the dependent end-expiratory lung volumes (ΔEELV dep (a) and improved oxygenation [PaO 2 /FiO 2 ratio (oxygen partial arterial pressure/oxygen inspired fraction ratio)] (b) in a linear fashion in comparison to standard facial mask oxygen. Filled circles represent individual patients' value at each flow rate while the horizontal line is the mean value. § indicates p <0.05 by post-hoc Bonferroni test vs. Facial mask. ° indicates p <0.05 by post-hoc Bonferroni test vs. HFNC 30

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that in AHRF patients, HFNC at increasing flow rates improved inspiratory drive and effort, oxygenation, efficiency of minute ventilation, end-expiratory lung volume and lung mechanics. The improvement of oxygenation, end-expiratory lung volume and mechanics showed a linear correlation with flow rates, with nearly constant improvement at increasing flow. In contrast, correlations between flow rates, effort and minute ventilation were better described by exponential fitting, with most of the improvement in these variables already obtained at 30 l/min. Finally, optimum flow for each physiologic variable studied did not always correspond to the highest flow rate (i.e. 60 l/min), with considerable variability between patients, indicating that personalized bedside titration of HFNC flow rate (possibly starting from the highest working downwards) seems warranted.

We observed that optimum flow (i.e. the flow rate at which the highest improvement from baseline achieved by most patients) can be different for each target variable; this variability should be considered when attempting to individualize HFNC settings. Indeed, considering averaged results, to obtain the highest improvement in oxygenation, one might set the flow rate at 60 l/min (or at the highest value tolerated by the patient). On the other hand, maximal reduction in effort and work of breathing might be achieved in most patients by setting a lower flow rate (e.g. 30 l/min). In a few subjects, an even further reduction in the work of breathing could be obtained at higher flow rates. Our data suggest that individualized settings of HFNC might be of key importance to fully exploit the clinical benefits. However, in clinical practice, time constraints may limit the possibility of assessing serial variations of target physiological variables at different flow rates to identify the “personalized” optimum flow. Thus, it might also be reasonable to simplify the clinical approach to the selection of the highest flow tolerated by the patient, starting from 60 l/min.

The patient cohort in this study comprised adult patients with AHRF who were diagnosed within a few days in the ICU. We explored the effects of HFNC randomly delivered at increasing flow rates on drive and effort, lung volumes, mechanics and oxygenation on these patients [8]. Vargas et al. measured patient’s drive, effort and gas exchange in a population of patients with AHRF who had been admitted to the ICU and described significant physiologic improvements during HFNC in comparison to the facial mask. In that study, the PTPPes was measured with the same method used in our study and showed similar variations. However, HFNC was delivered only at a single flow rate of 60 l/min, and no monitoring of lung volumes (either tidal or end-expiratory) was implemented [25]. To date, only a few studies have described the effects of increasing HFNC flow rates, and all were conducted only on healthy subjects and on post-cardiac surgery and weaned patients after long-term ventilation without actual acute respiratory failure [13,14,15,16,17,18]. The authors of these studies describe increased hypo-pharyngeal and tracheal pressures and improved EELV at increasing flow rates (both results suggesting a PEEP effect), decreased respiratory rate (possibly indicating decreased respiratory drive) and higher arterial oxygenation (likely by the better matching of patient’s alveolar and set HFNC FiO2) [10, 13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, none of these studies assessed the physiologic effects of HFNC delivered at increasing flow rates in patients with AHRF.

A key beneficial effect of HFNC might be the reduction of inspiratory drive and effort induced by improved CO2 clearance, improved lung mechanics, external respiratory support and decreased hypoxic respiratory drive [12, 25, 26]. In our study, we observed that swings in the inspiratory esophageal pressure and pressure–time product, both accepted measures of a patient’s effort, decreased during HFNC and that improvement in these variables correlated (albeit non-linearly) with increasing flow rates. Indeed, among patients, optimum flow distribution for ΔPes was more skewed (i.e. 43% had highest reduction at 30 or 45 l/min) than was lung volume or oxygenation. These findings may suggest that, in AHRF patients, most of the reduction in the effort and work of breathing can be obtained at even the lowest flow rate of 30 l/min. A possible explanation may be that CO2 might be effectively washed-out from the upper respiratory tract already at 30 l/min, as shown also in a previous study [27], together with similar decay of the minute ventilation needed to maintain physiologic PaCO2. We could also speculate that “physical” barriers (e.g. anatomical conformation of the glottis) might preclude higher HFNC flows to reach the trachea, thus impeding further improvement in the efficiency of CO2 wash-out at 45 and 60 l/min. The preliminary nature of our data precludes definitive conclusions on the correlation between increasing HFNC flow rates and inspiratory effort, work of breathing and CO2 wash-out. Further studies measuring CO2 tension in the upper airways during HFNC at increasing flow rates in AHRF patients may help to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Data on post-cardiac surgery patients without AHRF suggest that HFNC delivered at 35–50 l/min generates relatively low positive expiratory airway pressure (PEEP effect; around 3 cmH2O measured via a nasopharyngeal catheter) [28] and that this effect is not correlated with the patient keeping the mouth either open or closed. However, in another study, which measured the airway pressure via a trans-tracheal catheter, Chanques et al. reported that the PEEP effect of HFNC delivered at 45 l/min was significantly reduced by asking the patient to breathe with the mouth open [18]. In our study, we did not measure hypo-pharyngeal pressure as an estimate of airway pressure, nor did we instruct the patients to keep the mouth closed to maximize the PEEP effect. Nonetheless, the PEEP effect was indirectly suggested by an increase in EELV during HFNC (for which it is difficult to find an alternative explanation for increased end-expiratory transpulmonary pressure), and the lack of instructions on mouth opening/closing greatly enhance the clinical translation of our findings. Lower EELV values measured during HFNC in a few patients may correspond to breathing with the mouth open coupled with decreased dynamic driving transpulmonary pressure (i.e. ΔPes), possibly inducing alveolar de-recruitment. EIT monitoring suggests that the increase in EELV was mainly due to linear improvement of the regional end-expiratory volume in the dependent zones. Improvement of dependent lung volume was associated with an increase in dynamic lung compliance and peripheral arterial oxygenation in a similar linear fashion. It has been shown that alveolar recruitment induced by the application of higher PEEP levels is mostly located in the gravitationally dependent lung regions [29] and that it is associated with improved lung mechanics and reduced intrapulmonary shunt fraction. These observations generate the hypothesis that the PEEP effect obtained by HFNC might increase with the set flow rate (which seems reasonable as the PEEP induced by HFNC should be related to increased expiratory resistance) and that this PEEP effect might induce regional recruitment. An optimum flow value of 60 l/min for all these variables supports this reasoning. On the other hand, we must acknowledge that oxygenation may have improved at higher flow rates by better matching between delivered HFNC flow and inspiratory flow of dyspneic AHRF patients, which increases the alveolar FiO2 for a given set FiO2 [10].

Our study has several limitations. First, the study phases were short; however, based on previous studies, 20 min should be a sufficiently long time period to obtain a stable effect on effort, lung volumes and gas exchange. Second, EIT images display approximately one-half the area of the lungs and therefore cannot be used to measure lung volume changes along the vertical axis. In addition, most of the validation studies of EIT compared with other techniques have been conducted in different settings (e.g. intubated patients or animal models). However, previous studies have shown good agreement between the findings of EIT and other reference methods that measure whole lung volume [30, 31]. Third, albeit in line with previous studies, our sample size was small, which may have precluded the observation of significant differences. This could be even more relevant in our study, which was designed as a physiologic study but which generates a lot of information with the potential to change clinical practice regarding the selection of HFNC flow rate. Fourth, we included AHRF patients with both mono- and bilateral infiltrates on chest X-ray, which may have introduced some heterogeneity. Fifth, we did not record whether the patient’s mouth was open or closed during data collection, potentially missing a physiologic explanation for some of the findings (e.g. decreased EELV at higher HFNC flow rate). Sixth, we did not measure patients’ comfort but assessed changes in physiologic measures of patients’ respiratory condition. In addition to the physiologic effects of intensive care therapies, patients’ comfort and preference also need to be considered regularly. Seventh, optimum flow rate was selected as the flow rate inducing the highest absolute change from baseline of each physiologic parameter in most patients. Thus, even small differences with apparently limited clinical relevance may have contributed to the definition of optimum flow.

Conclusions

In patients with AHRF, HFNC delivered at increasing flow rates linearly improves respiratory drive, end-expiratory lung volume, lung mechanics and oxygenation, while effort and minute ventilation decreases in an exponential way, with most of the effects already obtained at a flow rate of 30 l/min. Individual improvements may be highly heterogeneous, and ideally the HFNC optimum flow rate should be personalized, rather than being based on average population values. In the real-life ICU setting, time constraints could hinder accurate flow titration based on the target physiologic parameter, and a simplified approach with selection of the highest flow rate tolerated by the patient, starting from 60 l/min, may be a reasonable alternative.

References

Papazian L, Corley A, Hess D, Fraser JF, Frat JP, Guitton C, Jaber S, Maggiore SM, Nava S, Rello J, Ricard JD, Stephan F, Trisolini R, Azoulay E (2016) Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygenation in ICU adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 42(9):1336–1349

Nishimura M (2016) High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults: physiological benefits, indication, clinical benefits, and adverse effects. Respir Care 61(4):529–541

Maggiore SM, Idone FA, Vaschetto R, Festa R, Cataldo A, Antonicelli F, Montini L, De Gaetano A, Navalesi P, Antonelli M (2014) Nasal high-flow versus Venturi mask oxygen therapy after extubation. Effects on oxygenation, comfort, and clinical outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190(3):282–288

Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, Girault C, Ragot S, Perbet S, Prat G, Boulain T, Morawiec E, Cottereau A, Devaquet J, Nseir S, Razazi K, Mira JP, Argaud L, Chakarian JC, Ricard JD, Wittebole X, Chevalier S, Herbland A, Fartoukh M, Constantin JM, Tonnelier JM, Pierrot M, Mathonnet A, Béduneau G, Delétage-Métreau C, Richard JC, Brochard L, Robert R, FLORALI Study Group; REVA Network (2015) High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 372(23):2185–2196

Stéphan F, Barrucand B, Petit P, Rézaiguia-Delclaux S, Médard A, Delannoy B, Cosserant B, Flicoteaux G, Imbert A, Pilorge C, Bérard L, BiPOP Study Group (2015) High-flow nasal oxygen vs noninvasive positive airway pressure in hypoxemic patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 313(23):2331–2339

Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, Subira C, Frutos-Vivar F, Rialp G, Laborda C, Colinas L, Cuena R, Fernández R (2016) Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315(13):1354–1361

Hernández G, Vaquero C, Colinas L, Cuena R, González P, Canabal A, Sanchez S, Rodriguez ML, Villasclaras A, Fernández R (2016) Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs noninvasive ventilation on reintubation and postextubation respiratory failure in high-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316(15):1565–1574

Mauri T, Turrini C, Eronia N, Grasselli G, Volta CA, Bellani G, Pesenti A (2017) Physiologic effects of high-flow nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195(9):1207–1215

Spoletini G, Alotaibi M, Blasi F, Hill NS (2015) Heated humidified high-flow nasal oxygen in adults: mechanisms of action and clinical implications. Chest 148:253–261

Chikata Y, Onodera M, Oto J, Nishimura M (2017) FIO2 in an adult model simulating high-flow nasal cannula therapy. Respir Care 62(2):193–198

Lee JH, Rehder KJ, Willford L, Cheifetz IM, Turner DA (2013) Use of high flow nasal cannula in critically ill infants, children, and adults: a critical review of literature. Intensive Care Med 39(2):247–257

Möller W, Feng S, Domanski U, Franke KJ, Celik G, Bartenstein P, Becker S, Meyer G, Schmid O, Eickelberg O, Tatkov S, Nilius G (2017) Nasal high flow reduces dead space. J Appl Physiol 122(1):191–197

Groves N, Tobin A (2007) High flow nasal oxygen generates positive airway pressure in adult volunteers. Aust Crit Care 20(4):126–131

Parke RL, Eccleston ML, McGuinness SP (2011) The effects of flow on airway pressure during nasal high flow oxygen therapy. Respir Care 56(8):1151–1155

Parke RL, Bloch A, McGuinness SP (2015) Effect of very-high-flow nasal therapy on airway pressure and end-expiratory lung impedance in healthy volunteers. Respir Care 60(10):1397–1403

Parke RL, Bloch A, McGuinness SP (2013) Pressure delivered by nasal high flow oxygen during all phases of respiratory cycle. Respir Care 58(10):1621–1624

Ritchie JE, Williams AB, Gerard C, Hockey H (2011) Evaluation of humified nasal high-flow oxygen system, using oxygraphy, capnography and measurement of upper airway pressures. Anaesth Intensive Care 39(6):1103–1110

Chanques G, Riboulet F, Molinari N, Carr J, Jung B, Prades A, Galia F, Futier E, Constantin JM, Jaber S (2013) Comparison of three high flow oxygen therapy delivery devices: a clinical physiological cross-over study. Minerva Anestesiol 79(12):1344–1355

Mojoli F, Chiumello D, Pozzi M, Algieri I, Bianzina S, Luoni S, Volta CA, Braschi A, Brochard L (2015) Esophageal pressure measurements under different conditions of intrathoracic pressure. An in vitro study of second generation balloon catheters. Minerva Anestesiol 81(8):855–864

Mojoli F, Iotti GA, Torriglia F, Pozzi M, Volta CA, Bianzina S, Braschi A, Brochard L (2016) In vivo calibration of esophageal pressure in the mechanically ventilated patient makes measurements reliable. Crit Care 20(1):98

Mauri T, Yoshida T, Bellani G, Goligher E, Carteaux G, Rittayamai N, Mojoli F, Chiumello D, Piquilloud L, Grasso S, Jubran A, Laghi F, Magder S, Pesenti A, Loring S, Gattinoni L, Talmor D, Blanch L, Amato M, Chen L, Brochard L, Mancebo J, the PLeUral pressure working Group (PLUG—Acute Respiratory Failure section of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine) (2016) Esophageal and transpulmonary pressure in the clinical setting: meaning, usefulness and perspectives. Intensive Care Med 42:1360–1373

Mauri T, Eronia N, Abbruzzese C, Marcolin R, Coppadoro A, Spadaro S, Patroniti N, Bellani G, Pesenti A (2015) Effects of sigh on regional lung strain and ventilation heterogeneity in acute respiratory failure patients undergoing assisted mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 43(9):1823–1831

Bellani G, Mauri T, Coppadoro A, Grasselli G, Patroniti N, Spadaro S, Sala V, Foti G, Pesenti A (2013) Estimation of patient’s inspiratory effort from the electrical activity of the diaphragm. Crit Care Med 41(6):1483–1491

Wexler HR, Lok P (1981) A simple formula for adjusting arterial carbon dioxide tension. Can Anaesth Soc J 28(4):370–372

Vargas F, Saint-Leger M, Boyer A, Bui NH, Hilbert G (2015) Physiologic effects of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen in critical care subjects. Respir Care 60(10):1369–1376

Mundel T, Feng S, Tatkov S, Scheneider H (2013) Mechanisms of nasal high flow on ventilation during wakefulness and sleep. J Appl Physiol 114(8):1050–1065

Onodera Y, Akimoto R, Suzuki H, Masaki N, Kawamae K (2017) A high-flow nasal cannula system set at relatively low flow effectively washes out CO2 from the anatomical dead space of a respiratory-system model. Korean J Anesthesiol 70(1):105–106

Corley A, Caruana LR, Barnett AG, Tronstad O, Fraser JF (2011) Oxygen delivery through high-flow nasal cannulae increase end-expiratory lung volume and reduce respiratory rate in post-cardiac surgical patients. Br J Anaesth 107(6):998–1004

Crotti S, Mascheroni D, Caironi P, Pelosi P, Ronzoni G, Mondino M, Marini JJ, Gattinoni L (2001) Recruitment and derecruitment during acute respiratory failure: a clinical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164(1):131–140

Van der Burg PS, Miedema M, de Jongh FH, Frerichs I, van Kaam AH (2014) Cross-sectional changes in lung volume measured by electrical impedance tomography are representative for the whole lung in ventilated preterm infants. Crit Care Med 42(6):1524–1530

Mauri T, Eronia N, Turrini C, Battistini M, Grasselli G, Rona R, Volta CA, Bellani G, Pesenti A (2016) Bedside assessment of the effects of positive end-expiratory pressure on lung inflation and recruitment by the helium dilution technique and electrical impedance tomography. Intensive Care Med 42(10):1576–1587

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the present study.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Committee of the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy approved the study (reference number: 1628/2015), and informed consent was obtained from each patient according to local regulations.

Additional information

Take-home message:

In acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) delivered at increasing flow rates induced a significant improvement of the patient’s inspiratory effort, minute ventilation, lung volume, dynamic compliance and oxygenation. However, most of the effect on inspiratory workload and CO2 clearance was already obtained at lowest HFNC flow rate. A personalized setting could be considered after careful evaluation of patient’s condition and the individual response.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mauri, T., Alban, L., Turrini, C. et al. Optimum support by high-flow nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: effects of increasing flow rates. Intensive Care Med 43, 1453–1463 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4890-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4890-1