Abstract

Introduction

To determine the effects of tranexamic acid (TXA) on transfusions in patients undergoing hip replacement with a hybrid or cementless prosthesis.

Methods

A group of 172 consecutive patients aged 18 years or older who underwent elective hip replacement with uncemented or hybrid prostheses, undergoing surgery between January 2012 and January 2014 by the same primary surgeon and anesthesiologist, were retrospectively included. TXA (1 g) was administered immediately before incision in the TXA group. Primary variables included number of red blood cell transfusions and the influence of TXA for each type of prosthesis. Secondary variables included hematocrit at discharge, length of hospital stay, thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, seizures, and death.

Results

Average transfusion was 1.53 units/patient in the control group compared to 0.6 units/patient in the TXA group (z = 6.29; U = 1640.5; p < 0.0001). TXA use was significantly correlated with the number of units transfused (p < 0.0001, 95% CI −1.24 to −0.68). Odds risk reduction for transfusion was observed during surgery (OR: 0.14; CI 0.06–0.29; p < 0.0001) and during the rest of hospital stay (OR: 0.11; CI 0.01–0.96; p = 0.046). Both hybrid and cementless prostheses that received TXA were transfused less than control groups (0.57 ± 1 vs. 1.7 ± 1 p < 0.01 and 0.65 ± 1 vs. 1.24 ± 1 p < 0.01). No difference was observed between the groups regarding adverse effects. Hematocrit values at discharge and length of hospital stay were similar between groups. No deaths were observed during hospital stay.

Conclusions

TXA reduced transfusions without increasing the prevalence of adverse effects. This reduction was observed during surgery and the following days of hospital stay for both for hybrid and cementless prosthesis.

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung

Die Auswirkungen von Tranexamsäure (TXA) auf die Transfusionen bei Patienten, die sich einer Operation zur Implantation einer Hybrid- oder zementfreien Endoprothese unterzogen, werden bestimmt.

Methoden

Eine Gruppe von 172 konsekutiven Patienten ≥18 Jahren, die zwischen Januar 2012 und Januar 2014 im Rahmen einer Hüftoperation, die vom selben Chirurgen und Anästhesisten durchgeführt wurde, eine zementfreie oder Hybridendoprothese erhielten, wurden retrospektiv eingeschlossen. Die TXA (1 g) wurde in der TXA-Gruppe unmittelbar vor der Inzision injiziert. Die primären Variablen waren die Anzahl der übertragenen roten Blutkörperchen sowie der Einfluss von TXA auf jede Endoprothesenform. Die sekundären Variablen waren Hämatokrit bei Entlassung aus dem Krankenhaus, Hospitalisationsdauer, Thrombose oder Lungenembolie, Epilepsie und Tod.

Ergebnisse

Die durchschnittliche Transfusionsmenge betrug 1,53 Einheiten/Patient in der Kontrollgruppe verglichen mit 0,6 Einheiten/Patient in der TXA-Gruppe (z = 6,29; U = 1640,5; p < 0,0001). TXA korrelierte signifikant mit der Anzahl der übertragenen Einheiten (p < 0,0001; 95% CI −1,24 und −0,68). Während der Operation wurde eine Reduzierung des Odds-Ratios beobachtet (OR: 0,14; 95% CI 0,06–0,29; p < 0,0001) sowie auch während der übrigen Hospitalisationsdauer (OR: 0,11; 95% CI 0,01–0,96; p = 0,046). Sowohl in der Gruppe mit Hybridendoprothese als auch in der Gruppe mit zementfreier Endoprothese, die beide TXA erhalten hatten, waren weniger Transfusionen nötig als bei den Kontrollgruppen (0,57 ± 1 vs. 1,7 ± 1; p < 0,01 und 0,65 ± 1 vs. 1,24 ± 1; p < 0,01). Hinsichtlich der unerwünschten Ereignisse wurde kein Unterschied zwischen den Gruppen festgestellt. Die Hämatokritwerte bei Entlassung und die Hospitalisationsdauer waren in beiden Gruppen ähnlich. Todesfälle während des Krankenhausaufenthalts gab es keine.

Schlussfolgerung

TXA reduzierte die Transfusionen, ohne das Auftreten unerwünschter Ereignisse zu erhöhen. Diese Reduzierung wurde während der Operation und in den folgenden Tagen des Krankhausaufenthalts sowohl in der Gruppe mit Hybridendoprothese als auch in der Gruppe mit zementfreier Endoprothese beobachtet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Total hip replacement (THR) is undeniably associated with substantial blood loss and high transfusion rates. Several techniques are currently employed to minimize the need for postoperative blood transfusions, including intraoperative autologous blood transfusion, intraoperative blood saving, spinal anesthesia, hypotensive anesthesia, and antifibrinolytic therapy [1].

A large number of previous reports have confirmed the efficacy of tranexamic acid (TXA) in reducing operative blood loss and further transfusion indications in patients undergoing elective total hip and knee arthroplasties [2, 3]. However, many of these studies have particular limitations related to their designs. Some analyzed the action of TXA without discriminating its particular effect on hip and knee replacements independently. Moreover, a varied dosing and timing schedule for TXA administration had been described, along with diverse anesthetic techniques and implant selection (cemented, cementless, or hybrid), which may be considered confounding variables in past studies [4, 5]. Finally, little has been written on the long-term safety of TXA use regarding unplanned hospital readmissions.

As a result, current orthopedic treatment guidelines continue to be controversial regarding the preferred TXA dosification strategy [6–8]. Therefore, we decided to study the effects of a preoperative single TXA dose, administered as an intravenous bolus, on transfusion rate, hospital stay, and mortality in patients undergoing THR performed by a single surgeon and using only spinal anesthesia performed by the same anesthesiologist.

Materials and methods

Study design

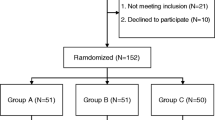

After obtaining the approval of our institution’s Research Ethics Board, we retrospectively studied a cohort of 205 consecutive patients aged 18 years or older who underwent primary THR between January 2012 and January 2014. This study was conducted under the Preferred Reported Items for the systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Demographic and surgical information were obtained from medical records at our prospectively collected electronic database. TXA administration, hospital stay, and readmissions were confirmed using our institutional billing records.

Patient population

We excluded 15 patients with bleeding disorders, as well as 18 who had been treated with anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapy due to history of thromboembolic disease. We included only 172 patients whose surgery was performed by the same experienced surgeon (MB) and qualified anesthesiologist (AF). Given a standardized protocol developed at our institution, patients with a history of chronic renal failure, cirrhosis, venous thromboembolic disease, or epilepsy are not eligible candidates to receive an intravenous prophylactic dose of TXA. All patients were operated by the same surgical technique, i.e., through a minimally invasive posterolateral approach in a lateral decubitus position. In cases of hybrid implants and a third-generation cementing technique was utilized for stem introduction. Spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine hydrochloride (10–15 mg) + fentanyl (25 µg) and sedation with a continuous propofol infusion were used in all cases. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy consisted of an intravenous administration of 2 g of cephazoline immediately before surgery, followed by 1 g every 8 h only during the following hospital day.

Groups and study variables

We divided our study population in two groups. Patients who received a single intravenous dose of 1 g of acid tranexamic immediately before incision were included in the TXA group, whereas patients who did not receive it comprised the control group. In addition, we classified the surgeries in uncemented or hybrid prosthesis depending on the use of a cemented stem. Patient characteristics studied were age, sex, weight, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, surgery extent, and preoperative hematocrit (Ht). Primary studied variables included number of red blood cell (RBC) units (allogeneic or both allogeneic and autologous), odds risk for transfusion in general and specific odds risk of transfusion of more than 1 RBC unit. Since the anesthesiologist transfusion protocol differed from the one used by the general internist during inpatient stay; we separately studied, on the one hand, transfusions that were performed during surgery and in the immediate postoperative recovery unit and, on the other, those indicated during the following postoperative days. We developed a subanalysis to evaluate the influence of tranexamic acid among each type of prosthesis selected (hybrid or cementless). Secondary variables included hematocrit at discharge, length of hospital stay, the presence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), seizures, readmissions, and mortality. Readmission was defined as an inpatient stay within a 90-day period after discharge by the same patient, related or not to an issue inadequately resolved during the prior hospitalization.

Transfusion protocols

Patients were transfused using two protocols during their hospital stay. The transfusion protocol for surgery and immediate recovery unit stay, included the following criteria: (1) If hemoglobin (Hb) was 8 g/dl or less, (2) if Hb was below 10 g/dl in patients with cardiovascular disease (a history of ischemic heart disease, electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction, a history or presence of congestive heart failure or peripheral vascular disease, or a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack), (3) if there was hypotension or tachycardia unresponsive to fluid resuscitation, or clinical evidence of major active bleeding. Likewise, transfusion protocol during the postoperative hospital stay was performed when (1) Hb was 7 g/dl or less, (2) hematocrit was of 20% or lower.

Statistics

Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile range. Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. Multiple regression analysis was performed using the number of RBC units transfused as the independent variable and compared with age, weight, preoperative hematocrit, surgical time and tranexamic administration. Odds ratio results are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 2.7.0).

Results

During the analyzed period, 172 patients underwent primary THR. Mean surgery time was 59 min (range 30–82 min). A total of 85 patients (49%) received a single intravenous bolus of 1 g of TXA immediately before surgical incision. Patient demographics and surgical characteristics were similar between the TXA and the control groups (Table 1).

A total of 184 units of RBC were transfused between both groups. Average RBC transfusion was 1.53 units/patient in the control group compared to 0.6 units/patient in the TXA group (z = 6.29; U = 1640.5; p < 0.0001). None of the patients were transfused before surgery. In a multiple regression analysis, the number of RBC units transfused showed no significant correlation with age, ASA score, type of prosthesis, weight, preoperative hematocrit, and surgery duration. The sole use of tranexamic acid presented a statistically significant correlation with the number of RBC units transfused (p < 0.0001 CI 95% −1.24 to −0.68) (Fig. 1).

Transfusion of at least 1 allogeneic unit of RBC occurred in 36 patients in the TXA group and in 76 patients in the control group. An 89.4% (OR: 0.106; CI 0.05–0.23; p < 0.0001) odds risk reduction for transfusion of at least 1 unit of erythrocyte blood cell was observed in the TXA group. This strong risk reduction persisted when transfusion of more than 1 unit was analyzed (Table 2).

In a subanalysis, we analyzed the moment of transfusion. During surgery and immediate postoperative recovery unit stay 42% of the patients in the tranexamic group and 83% of the patients in the control group received transfusions. During the following hospital stay, 1 patient (1.1%) in the tranexamic group and 8 patients (9.2%) in the control group received transfusions. This issue resulted in a significant reduction of the odds risk for transfusion of at least 1 unit of RBC during surgery and immediate recovery unit stay (OR: 0.14; CI 0.06–0.29; p < 0.0001) and for transfusion during the rest of hospital stay (OR: 0.11; CI 0.01–0.96; p = 0.046).

When transfusion rate according to the type of prosthesis was studied, regardless of the use of TXA, no difference was observed between hybrid and cementless prosthesis both during the surgery/immediate recovery unit stay or during the rest of hospital stay (p = 0.13 and p = 0.3, respectively). Likewise, we observed that both hybrid and cementless prosthesis that received tranexamic were transfused significantly less than each control group, respectively (0.57 ± 1 vs. 1.7 ± 1 p < 0.01 and 0.65 ± 1 vs. 1.24 ± 1 p < 0.01; Fig. 2).

No significant differences were observed between the groups regarding DVT, PE, seizures, or readmissions. Only one patient of the series, who belonged to the TXA group, presented with a seizure that was medically treated. Six patients (6.9%) from the control group were readmitted within the following 90 days after discharge, as described in Table 3. Two of these 6 were diagnosed with deep infection of the surgical site and were subsequently treated with surgical debridement and irrigation along with intravenous antibiotics. On the other hand, 3 patients (3.5%) of the TXA group were readmitted; none of them diagnosed with surgical site infection. Patients’ hematocrit values at discharge and length of hospital stay were similar between both groups. No deaths were observed during hospital stay (Table 4).

Discussion

The presented report has focused its main asset in RBC transfusion reduction with the use of TXA, as many articles have previously outlined. However, this study additionally provides an in-depth analysis of the use of TXA considering potential well-known associated complications such as DVT or even those not so notorious such as seizures; as well as it offers an evaluation of hospital readmissions in order to categorize it as an independent protective factor. According to our results, a single dose of 1 g of TXA administered immediately before incision considerably reduced the need of RBC transfusions in patients undergoing primary THR under spinal anesthesia. This reduction was effective both for hybrid and cementless prosthesis and the beneficial effect was observed not only during surgery, but also during the rest of hospital stay. In addition, collateral complications and readmissions associated with the use of TXA were low, although not significantly different from the control group.

Several studies have proved the beneficial effect of TXA on transfusions in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty [5, 9, 10] as well as of its advantageous effect in patients with preoperative anemia presenting for total joint arthroplasty [11]. However, the implicit biases on the choice of implants selected (uncemented or hybrid) and the type of anesthesia can be possible confounders. Traditional teaching has been that cemented or hybrid THRs have a higher total blood loss than uncemented THRs, given the longer surgical time of the former [12, 13].

Nonetheless, this premise is not universally accepted. When comparing hybrid, cemented and cementless THRs, a retrospective study done by Trice et al. [14] showed no evidence of different blood requirements between cemented and uncemented prosthesis. Moreover, in a previous study that was originally designed to compare two thromboprophylactic drugs where tranexamic acid was administered according to the surgeon’s preference, Rajesparan et al. [15] found that TXA was effective on reducing both the amount of bleeding and the need for allogeneic blood transfusion in patients with cemented, cementless, and hybrid THA who received different anesthetic methods. A more recent randomized controlled trial concluded that combining local and systemic TXA in primary elective cementless THR proved to increase postoperative levels of hemoglobin and reduce total blood loss when compared to isolated local or intravenous administration [16]. In our study on 172 patients, no difference in the ratio of transfusions between hybrid and cementless prosthesis was observed; and TXA strongly reduced the need of transfusions for both type of arthroplasties. Unlike previous studies, the surgeon and anesthesiologist were the same for all patients and spinal anesthesia was used in all cases. We believe that our results reinforce the safety and efficacy of TXA in THR and, on the other hand, contribute to elucidate the yet not clearly established influence of TXA on the different types of prosthesis commonly used.

The half-life of 1000 mg of intravenously administered TXA has been found to be 1.9 h [17] and the concentration of TXA in the plasma remains above the minimum therapeutic level for approximately 3 h after a 10 mg/kg dose [18, 19]. Those findings are consistent with previous observations that demonstrated significant reductions in blood loss for as long as 4 h [20]. In agreement with these findings, transfusion rate during surgery and immediate recovery unit was strongly reduced in the TXA group, in which an average surgery duration of 59 min was found. Therefore, our observation of a reduced transfusion rate during the rest of the hospital stay (when TXA is below therapeutic levels) may be interpreted as a beneficial effect arising from an initially improved hemostasis.

Although TXA is an inhibitor of fibrinolysis that does not affect initial clot formation, there is a theoretical concern associated with its use and a potential for inducing thromboembolic events [21, 22]. Zhang et al. [10] concluded after conducting a randomized-controlled study that topical administration of TXA proved to be safer and more effective than intravenous TXA. However, previous investigations reported no increased risk of thromboembolic disease even in patients with a history of pulmonary embolism [4, 23–25]. In agreement with these results, the difference in DVT and PE rate between both groups of our study was neither significant nor clinically relevant, and falls within the currently reported range after elective total hip replacement.

Seizures have been associated with the use of TXA in several clinical studies specially after cardiac surgery, old patients, and in patients with impaired renal function [26, 27]. Moreover, animal studies have suggested that the reduction of GABAA receptor mediated inhibitory synaptic transmission via postsynaptic mechanisms produced by TXA could be responsible for promoting epileptiform activity in the central nervous system [28].To the best our knowledge, no previous investigation has addressed this adverse effect in a population undergoing THR and receiving TXA therapy. Our results showed one patient in the TXA group presenting seizure during the postoperative period. No seizures were registered in the control group. Although not statistically significant, this finding warrants for further analysis of this adverse effect in future studies and should be kept in mind by treating physician in all patients undergoing TXA therapy.

To our knowledge, there is no literature available relating the use of TXA and hospital readmissions. Although there was a trend towards more readmissions due to deep infection of the surgical site in the control group, our figures were not statistically significant to identify association between not using TXA and further hospitalization. Previous studies have strongly associated the presence of hematoma and prolonged wound drainage with the development of wound infection in patients undergoing hip replacement [29, 30]. Additionally, a systematic review of the literature, which aimed to evaluate the risk factors of infection after hip hemiarthroplasty, concluded that length of hospital stay, hematoma, prolonged wound drainage, time of surgery, use of uncemented stems, advanced age, and obesity were all risk factors contributing to surgical site infection [31]. We also believe that hematoma is a major risk factor for infections and with the advent of TXA a decrease in this complication may be expected. However, further clinical studies are needed to assess the validity of TXA as an independent protective factor for deep infections.

Other than its retrospective nature, this study is limited by the high transfusion rate observed that may be the result of subjective transfusion triggers such as hypotension or tachycardia unresponsive to fluid resuscitation or clinical evidence of major active bleeding. However, the 172 patients included underwent THR following a standardized technique by the same operating team (surgeon/anesthesiologist) and therefore the possible bias in the interpretation of subjective variables is reduced.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that a preoperative single dose of 1 g of TXA showed a 90% reduction in the need of transfusion following an elective THR, both for hybrid and uncemented implants. This reduction was observed both intraoperatively and during the following hospital stay days without any significant difference between hybrid and cementless prosthesis. In this series, the use of TXA did not appear to affect the prevalence of DVT, PE, readmissions, or seizures.

References

Taylor SE, Cross MH (2013) Clinical strategies to avoid blood transfusion. Anaesth Intensive Care Med 14:48–50. doi:10.1016/j.mpaic.2012.11.012

Barrachina B, Lopez-Picado A, Remon M et al (2016) Tranexamic acid compared with placebo for reducing total blood loss in hip replacement surgery. Anesth Analg 122:986–995. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001159

Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S et al (2014) Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ 349:g4829. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4829

Kim TK, Chang CB, Koh IJ (2014) Practical issues for the use of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22:1849–1858. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2487-y

Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM (2011) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93:39–46. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24984

Banerjee S, Issa K, Pivec R et al (2013) Intraoperative pharmacotherapeutic blood management strategies in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 26:379–385. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1353992

Mak JCS, Fransen M, Jennings M et al (2012) Evidence-based review for patients undergoing elective hip and knee replacement. ANZ J Surg 84:17–24. doi:10.1111/ans.12109

Memtsoudis SG, Bs MH, Russell LA et al (2013) Consensus statement from the consensus conference on bilateral total knee arthroplasty group. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471:2649–2657. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2976-9

March GM, Elfatori S, Beaulé PE (2013) Clinical experience with tranexamic acid during primary total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int 23:72–79. doi:10.5301/HIP.2013.10724

Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma X et al (2016) What is the optimal approach for tranexamic acid application in patients with unilateral total hip arthroplasty? Orthopäde. doi:10.1007/s00132-016-3252-y

Phan DL (2015) Can tranexamic acid change preoperative anemia management during total joint arthroplasty? World J Orthop 6:521. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i7.521

Machin JT, Batta V, Soler JA et al (2014) Comparison of intra-operative regimes of tranexamic acid administration in primary total hip replacement. Acta Orthop Belg 80:228–233

Clarke AM, Dorman T, Bell MJ (1992) Blood loss and transfusion requirements in total joint arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 74:360–363

Trice ME, Walker RH, D’Lima DD et al (1999) Blood loss and transfusion rate in noncemented and cemented/hybrid total hip arthroplasty. Is there a difference? A comparison of 25 matched pairs. Orthopedics 22:s141–s144. doi:10.1007/s00776-008-1317-4

Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE (2009) The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91:776–783. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.22393

Xie J, Ma J, Yue C et al (2016) Combined use of intravenous and topical tranexamic acid following cementless total hip arthroplasty: a randomised clinical trial. Hip Int 26:36–42. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000291

Sano M, Hakusui H, Kojima C, Akimoto T (1976) Absorption and excretion of tranexamic acid following intravenous, intramuscular and oral administrations in healthy volunteers. Rinsho Yakuri Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Ther 7:375–382. doi:10.3999/jscpt.7.375

Benoni G, Carlsson A, Petersson C, Fredin H (1995) Does tranexamic acid reduce blood loss in knee arthroplasty? Am J Knee Surg 8:88–92. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Husted H, Blønd L, Sonne-Holm S et al (2003) Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusions in primary total hip arthroplasty: a prospective randomized double-blind study in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 74:665–669. doi:10.1080/00016470310018171

Yamasaki S, Masuhara K, Fuji T (2005) Postoperative blood loss in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87–A:766–770

Ho KM, Ismail H (2003) Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care 31:529–537

Lindoff C, Rybo G, Astedt B (1993) Treatment with tranexamic acid during pregnancy, and the risk of thrombo-embolic complications. Thromb Haemost 70:238–240

Gandhi R, Evans HMK, Mahomed SR, Mahomed NN (2013) Tranexamic acid and the reduction of blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes 6:184. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-6-184

Lin ZX, Woolf SK (2016) Safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of tranexamic acid in orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics 39:119–130. doi:10.3928/01477447-20160301-05

Gillette BP, DeSimone LJ, Trousdale RT et al (2013) Low risk of thromboembolic complications with tranexamic acid after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471:150–154. doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2488-z

Bell D, Marasco S, Almeida A, Rowland M (2010) Tranexamic acid in cardiac surgery and postoperative seizures: a case report series. Heart Surg Forum 13:E257–9. doi:10.1532/HSF98.20101014

Murkin JM, Falter F, Granton J et al (2010) High-dose tranexamic acid is associated with nonischemic clinical seizures in cardiac surgical patients. Anesth Analg 110:350–353. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c92b23

Kratzer S, Irl H, Mattusch C et al (2014) Tranexamic acid impairs γ‑aminobutyric acid receptor type a‑mediated synaptic transmission in the murine amygdala: a potential mechanism for drug-induced seizures? Anesthesiology 120:639–649. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000103

Cordero-Ampuero J, De Dios M (2010) What are the risk factors for infection in hemiarthroplasties and total hip arthroplasties? Clin Orthop Relat Res 468:3268–3277. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1411-8

Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S et al (2002) Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res 20:506–515. doi:10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00153-X

Noailles T, Brulefert K, Chalopin A et al (2015) What are the risk factors for post-operative infection after hip hemiarthroplasty? Systematic review of literature. Int Orthop. doi:10.1007/s00264-015-3033-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Fígar, S. Mc Loughlin, P.A. Slullitel, W. Scordo, and M.A. Buttaro declare that they have no competing interests.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Board of our institution “Comité de Etica de Protocolos de Investigación (CEPI)”; “Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires”. The present study was waived from informed consent by the Ethics Review Board due to its retrospective design. All details that might disclose the identity of the subjects under study have been omitted.

Additional information

Authors contribution: Fígar A, Mc Loughlin S, and Slullitel PA designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; Scordo W provided data from the blood bank and transfusions; Buttaro MA performed the surgeries and overviewed analysis and final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fígar, A., Mc Loughlin, S., Slullitel, P.A. et al. Influence of single-dose intravenous tranexamic acid on total hip replacement. Orthopäde 46, 359–365 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-016-3352-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-016-3352-8