Abstract

Aim

To describe trends in and characteristics of sedative drug use from 2000 through 2019 in relation to the introduction of central regulations and new drugs.

Methods

In this descriptive study, we used individual prescription data on the entire Danish population from the Danish National Prescription Registry to calculate yearly incidence and prevalence of use of benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine-related drugs (Z-drugs), melatonin, olanzapine, low-dose quetiapine, mianserin/mirtazapine, pregabalin, and promethazine from 2000 through 2019. From the Danish National Patient Registry, we obtained data on drug users’ psychiatric and somatic comorbidity.

Results

The use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs declined gradually from 2000 through 2019, whereas the newer alternatives, melatonin, low-dose quetiapine, pregabalin and promethazine, increased in use, while the use of olanzapine and mianserin/mirtazapine was relatively stable. This development was seen in both men and women and across all age groups except for hypnotic benzodiazepines which showed a steep increase in the oldest age group from 2010. For all sedative drugs depression, anxiety, alcohol and misuse disorder, pain and cancer were the most prevalent comorbidities. During our study period, the number of individuals without any of the selected diagnoses increased.

Conclusion

In Denmark different central regulations have influenced prescription practice toward more restrictive use of Z-drugs and benzodiazepines, except for hypnotic benzodiazepine prescriptions increased after the introduction of special palliative care. An increase in use of newer sedative drugs, however, indicates that the regulations do not remove the need for sedative drugs in the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, sedative drugs such as benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine-related drugs (Z-drugs), melatonin receptor agonists, sedating antipsychotics, antidepressants and antihistamines are widely prescribed for sedation, e.g. in the treatment of insomnia and anxiety [1, 2]. The use of barbiturates, widespread in the first half of the twentieth century, quickly declined due to the risk of addiction, toxicity, and potential overdose, once the less harmful benzodiazepines were introduced in the 1960s [3]. Similarly, due to addiction and tolerance issues [4], benzodiazepines were replaced in the 1980s by benzodiazepine-related drugs referred to as Z-drugs introduced and approved for insomnia. Z-drugs had less daytime impairment and were assumed to be less addictive than benzodiazepines [5, 6], but over the years the same concerns regarding tolerance, abuse, and addiction arose [4, 7] and recent studies have documented the risk of long-term use of both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs [8, 9] including risk of increased mortality [10] and decreased cognitive function [11]. Thus, the Danish Health Authorities have tried to limit their use through several guidelines and restrictions (Fig. 1).

Healthcare decisions and arrival of sedative drugs in Denmark from 1950s to 2019. Blue box = healthcare decisions, black box = introduction of new drugs. Guidelines meant to limit the prescriptions of sedative drugs (1956, 1980, 1993, 1995, 2003, 2007, 2013, 2018 and 2019). Tryghedskassen “Comfort Box” [11], was introduced in 2006, to relieve the symptoms in the last days of life in seriously ill individuals. It contains the following drugs: Morphine (opioid), Midazolam (hypnotic benzodiazepine), Haloperidol (antipsychotic), Furosemide (loop diuretic), Robinul (anticholinergic) and Natriumclorid, all drugs which can be administered as injection

In recent years, attempts have been made to develop new sedative drugs such as melatonin, which was introduced in 2007 for jetlag and insomnia [12]. Also, other drugs with sedative properties, initially approved for other indications, e.g. quetiapine, olanzapine, mianserin and mirtazapine, pregabalin and promethazine have been used off-label for their sedating properties (Fig. 1). Quetiapine was introduced in 2001 and has both sedating, antidepressant and antipsychotic effects. Low-doses quetiapine (25–100 mg, in the following referred to as low-dose quetiapine), however, are mainly given for sedation [13, 14]. Compared to quetiapine, olanzapine has antipsychotic properties at all doses, but it also has sedating side effects[13]. Mianserin and mirtazapine are given for depression, but also off-label for insomnia and they are often prescribed when sleep problems are prominent in the depressive episode [15]. Pregabalin was introduced in 2004 and has anxiolytic, analgesic, antiepileptic, and hypnotic effects. Its main indications are neuropathic pain and generalized anxiety, but due to its hypnotic effects it may also be used off-label for insomnia [16]. Finally, promethazine is a sedative antihistamine from the 1940s which has been sold over-the counter until December 2014. However, due to increased rates of suicidal attempts, it has since then been attainable only by prescription [17, 18]. Despite these developments, no studies have investigated how first-time prescriptions of the different sedative drugs in Denmark have developed over the past two decades.

The aim of the present study was to describe trends of sedative drug use and characteristics of the users from 2000 through 2019 in relation to the introduction of central regulations and new drugs.

Methods

Population

This descriptive study was based on information on the entire Danish population from nationwide registers. The study population was identified in the Danish Civil Registration System as individuals living above 10 years in Denmark between January 1st, 2000 to December 31st, 2019. Using the unique personal identification number (CPR) allowed us to link recorded individual-level information in all registers [19]. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data that were used under license for this study.

Sedative drugs

We used the Danish National Prescription Registry [20] to identify individuals with at least one filled prescription for sedative drugs during the study period. This registry contains information on all prescribed drugs dispensed at pharmacies since 1995, date of prescription redemption, and Anatomical Therapeutic Classification (ATC) code. Sedative drugs were defined by ATC-codes under the following drug classes: hypnotic benzodiazepines (N05CD), anxiolytic benzodiazepines (N05BA), benzodiazepine-related drugs (Z-drugs (N05CF)), melatonin (N05CH01), quetiapine (N05AH04), olanzapine (N05AH03), mianserin and mirtazapine (N06AX03 & N06AX11), pregabalin (N03AX16), and promethazine (R06AD02). For quetiapine, in line with previous studies, a low-dose subset defined as a prescription with a daily dose below 100 mg was extracted [13, 15, 21].

Covariables

We included information on individuals’ sex and date of birth from the Danish Civil Registration System, as both age and sex were assumed to be associated with sedative drug use [22,23,24]. Age was categorized into one of the following four groups: (10–44 years, 45–64, 65–79 and above 80 years).

Information on comorbidity was included as either hospital diagnoses or use of specific medication using International Classification of Disease 10th edition (ICD-10) diagnoses and ATC-codes from the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry, respectively. Since 1995, the National Patient Registry has included information on diagnoses, assigned by the physician at discharge for all visits (on emergency, in-, or outpatient basis) to Danish hospitals, whereas the National Prescription Registry contains information on all prescribed drugs dispensed at pharmacies since 1995 [20]. All psychiatric and somatic covariables were defined as at least one hospital contact with below-mentioned ICD10 codes or at least one purchase of medication with a below-mentioned ATC code during a 5-year period before the years 2000, 2010 and 2019 and were chosen as they were assumed to be associated with usage of sedative drugs [22, 25, 26]. We included the following psychiatric diseases: Schizophrenia (F20–F29), bipolar disorder (F30–F31), depression (F32–F33 and ATC-code N06D), anxiety (F40–F49), alcohol and drug misuse (F10–F19), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (F90 and ATC-code N06B), insomnia (G470) and insomnia not due to a substance or known physiological condition (F510), autism spectrum disorder (F840, F841, F845, F858, F849), and opioid prescriptions (ATC-code N02A) as well as the following somatic diseases: Ischemic heart disease (I20-25), diabetes (E10-14 and ATC-code A10), cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) (C00-C98 excl. C44), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (JR42-44), pain (R52, R529), and dementia (F00-03, G30 and ATC-code N06D). Finally, “No diagnoses” were defined as not having any of the above-mentioned diagnoses within the past 5 years.

Statistics

For each calendar year since 2000 through 2019, we calculated yearly prevalence as the total numbers of drug users divided by the population base and incidence as the number of new users divided by the same population base. As drug use varies with sex and age, we also calculated sex and age-specific incidence, prevalence rates and duration index. A duration index is a parameter to estimate turn-over in incidence and prevalent users, i.e. the average duration of medicine use, and it was calculated according to the WHO recommendations [27], using the following equation:

where D was the duration index, p was the point prevalence and i was the incidence. The point prevalence was deducted by following equation [28]:

where pw is the point prevalence rate at start of the time window, perpw is the period prevalence rate for the time window, iw is the incidence rate within the time window, and dtw is the width of time window.

The equation was reduced to the following:

The incidences was calculated by counting the number of new users in each year divided with the total population for each year. Our prevalence was calculated as the total numbers of users divided with the total population for each year. Thus, the point prevalence as of January 1st, 2019, would be the prevalence in year 2019 subtracted by the incidence in year 2019 (see Eq. 2). With the assumptions of the incidence and prevalence being in equilibrium [28], the point prevalence and the incidence can be divided to calculate the average duration of treatment, D (see Eq. 1).

Last, we calculated the prevalence of morbidities in incident and prevalent drug users for the three time periods 2000, 2010 and 2019.

Results

Time trends in sedative drug use

In the year 2000, anxiolytic benzodiazepines (11.6 new users per 1000 inhabitants, dotted-black line) and Z-drugs (11.1 new users per 1000 inhabitants, squared-gray line) were the most frequently prescribed sedative drugs (Fig. 2). During the 20-year period, the usage of these medications continuously declined and in 2019, melatonin (5.9 new users per 1000 inhabitants, triangled-yellow line), Z drugs (4.2 new users per 1000 inhabitants, squared-gray line), mianserin and mirtazapine (3.8 new users per 1000 inhabitants, purple line), and promethazine (3.7 new users per 1000 inhabitants, tilted-squared-blue line) were the most commonly purchased. In general, an increasing trend was seen for most medications except for anxiolytic and hypnotic benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, mianserin/mirtazapine and olanzapine. For promethazine, the incidence rates showed a steep increase in all age groups from 2014 (when promethazine became obtainable by prescription only), which was expected, as we only had access to redeemed prescriptions and not over-the-counter medications.

Trends in first-time prescriptions (incidence per 1000 inhabitants) of sedative drugs in Denmark 2000–2019. Z-drugs (squared gray), anxiolytic benzodiazepines (dotted black), hypnotic benzodiazepines (dotted orange), low-dose quetiapine (tilted squared green), promethazine (tilted squared light blue), pregabalin (dotted dark blue), mianserin & mirtazapin (purple), olanzapine (brown) and melatonin (triangled yellow). *Until 2014 sold over the counter

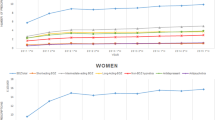

Figure 3 gives the incidence of prescriptions of sedative drugs by age. Generally, it shows similar time trends across all age-groups, also after stratifying on sex (supplementary Sect. 4). One exception was hypnotic benzodiazepines, (top center left) which from 2010 showed a marked increase in individuals of 80 years or above, primarily administered as injection (see Supplementary Fig. 1). For all drugs, there was a consistent increase in incidences with age implying that the age-group above 80 years had the highest incidence per 1000 inhabitants. The use among the oldest individuals seemed especially pronounced for use of olanzapine, low-dose quetiapine and mianserin/mirtazapine. For mianserin and mirtazapine there was a linear increase in incidence with age. For pregabalin, the incidence rates increased in the entire period, reaching 7.12 per 1000 inhabitants for the age group above 80 years in 2019, whereas the use was lower in the youngest age-group (10–44 years). For melatonin, the incidence increased in all age groups since the introduction in 2007 with a steep increase in the first years after its introduction (Fig. 3). When analyzing 10-year groups, we found the increase was largest among men in 10–19 years and 20–29 years (see Supplementary Fig. 2). However, for low-dose quetiapine the incidence was comparable among the 10–44 years, 45–64 years, and 65–79 years groups, but notably higher in patients above 80 years.

Trends in first-time prescriptions (incidence per 1000 inhabitants) of sedative drugs in Denmark by age subgroups, 2000–2019. Anxiolytic benzodiazepines (top left), hypnotic benzodiazepines (top center left), Z-drugs (top center right), melatonin (top right) Olanzapine (bottom left), low dose Quetiapine (bottom center left), Pregabalin (bottom center), Mianserin & Mirtazapine (bottom center right) and Promethazine [sold over the counter until 2014] (bottom left)

The duration index was relatively stable over the years for most sedative drugs (Fig. 4), suggesting the average treatment duration was stable in the study period. However, the most noteworthy change was for hypnotic benzodiazepines, for which the duration index declined from 7.4 years in 2008 to 0.8 years in 2019. Z-drugs had a relatively stable increase in duration index from 2.4 years in 2000 to 5.2 years in 2019.

Duration Index (Years) of selected sedative drugs (2000 to 2019). Duration index of hypnotic benzodiazepines (dotted orange), anxiolytic benzodiazepines (dotted black), Z-drugs (squared-grey), melatonin (triangled-yellow), olanzapine (brown), low-dose quetiapine (tilted-square-dotted-green), mianserin & mirtazapine (purple), pregabalin (dotted-blue) and promethazine (tilted-square-light-blue) [sold over the counter until 2014]

Characteristics of incident sedative drug users

The sociodemographic characteristics of the incident users is shown in Table 1. Women were more frequent users of most types of sedative drugs. From 2000 to 2019, there was a tendency towards a slight increase in male users for all drugs except promethazine. For most drugs, the median age at first prescription was above 50 years. Generally, the age of incident users was relatively stable across the years, except for hypnotic benzodiazepines for which there was a marked increase in median age of first prescription from 56 in 2000 to 80 in 2019. For promethazine, the median age increased from 2000 to 2019, but it should be taken into consideration that promethazine was sold “over-the-counter” before 2014 and prescription users may thus not represent most users before 2014.

Table 1 further shows the proportion of incident users of sedative drugs with a psychiatric and somatic comorbidity in in 2000, 2010 and 2019. In general, the proportion of users with a psychiatric comorbidity including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and alcohol and substance misuse declined among all drug classes during the study period, apart from promethazine. The prevalence of anxiety, ADHD and dementia also decreased for most drug types except for a marked increase in the proportion of users with dementia among hypnotic benzodiazepine users in 2019 as well as a decrease in the proportion of low-dose quetiapine users with dementia (Table 1). In general, the most notable decrease of psychiatric comorbidity was seen among users of low-dose quetiapine and, second, pregabalin users. Contrarily, the proportion of users with autism spectrum disorders and ADHD was relatively stable or slightly increasing across the years. From 2000 to 2010 when promethazine mainly was sold over the counter, we found increases in the prevalence of comorbid depression (27.5–43.1%), anxiety (6.9–12.8%) and alcohol (5.9% to 10.4%) and substance among those who had purchased the drug.

The most common psychiatric comorbidity among incident users of the sedative drugs across all time periods was depression, being most frequent among pregabalin users (77.5% in 2000), Mianserin & mirtazapine users (76.4% in 2000) and low-dose quetiapine users (77.9% in 2010), whereas almost half the individuals using benzodiazepines and Z-drugs had a comorbid depression in 2000. Anxiety and alcohol and substance misuse were the next most common comorbidities across the years. The most notable changes included a steep decrease in the proportion of alcohol misuse among users of hypnotic benzodiazepines from 2000 to 2019 (12.3% declining to 4.2%).

The most common somatic comorbidities among incident sedative drug users were opioid use followed by cancer. Generally, the prevalence of all somatic diseases decreased over time with the important exception of hypnotic benzodiazepines where somatic comorbidity including all diagnoses except for pain increased through the study period. This was especially seen for cancer comorbidity.

Finally, when examining the proportion of users without any of the included psychiatric or somatic comorbidity across the time periods, the proportion was highest for anxiolytic benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. The proportion of users without any comorbidity increased for all drug types across the years except for hypnotic benzodiazepines. The most notable increase was for users of low-dose quetiapine without any comorbidity which increased from 7.7% in 2010 to 24.2% in 2019, similar findings was done for mianserin and mirtazapine which increased from 13.7 in 2000 to 34.6 in 2019.

Discussion

This nationwide drug utilization study is the first to systematically investigate time trends and characteristics of incident users across a broad scope of sedative drugs in Denmark throughout two decades. It showed that the use of “traditional sedative drugs”, benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, declined gradually from 2000 through 2019, whereas the newer alternatives, melatonin, low-dose quetiapine, pregabalin, and promethazine, increased in use. This development was seen in both men and women and across all age groups except for hypnotic benzodiazepines which showed a steep increase in the oldest age group from 2010. The study also showed that for all sedative drugs depression, anxiety, alcohol and misuse disorder, opioid-use and cancer were the most prevalent comorbidities. Generally, the prevalence of both psychiatric and somatic comorbidity among sedative drug users decreased over time with the important exception of hypnotic benzodiazepines users, in whom there was a notable increase somatic comorbidity and dementia. Another notable change was a relatively high increase in users of low-dose quetiapine and mianserin/mirtazapine without psychiatric or somatic comorbidity.

Surprisingly, the incidence of prescriptions of anxiolytic benzodiazepines and Z-drugs was remarkedly high in Denmark in 2000, even though several guidelines implemented in the 1980s and 1990s had aimed to restrict the usage (Fig. 1). Hereafter, additional guidelines were released in the period 2001 to 2004 and alternative drugs with sedative effects such as melatonin, quetiapine and pregabalin were introduced. This together may have contributed to the decrease in the prescriptions of Z-drugs and anxiolytic benzodiazepines from 2003 to 2019. Previous drug utilization studies from Ireland [29], Japan [30] and Australia [31] have similarly shown a slight decreasing trend in benzodiazepines, whereas Z-drugs have showed more modest changes. Similar to our findings, the Australian study also found an increase in prescriptions of melatonin and quetiapine from 2011 through 2018 [31], whereas a Danish study reported increased use of melatonin among children and young people [32].

Insomnia is very common, and while cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is considered safe and efficient [33, 34], it remains restricted to a selected group of individuals [35], likely due to a lack of availability. However, as long as non-pharmacological treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia is not available, the different regulations in use of sedating drugs do not remove the need for sedating drugs in the population. Consequently, as the use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs was restricted, it is noticeable that melatonin, pregabalin and low-dose quetiapine all increased. Some could argue that this might show the willingness of doctors to prescribe drugs they are given access to prescribe. However, in Denmark, doctors do not get any financial or other compensation for making prescriptions, contrarily all prescriptions are monitored by the Health Authorities in order to regulate and stop potentially misuse. Finally, in our data, we only had access to purchased prescriptions, i.e. prescriptions that patients chose to purchase, and consequently, this might indicate the patients’ willingness to take the medication.

Another important question is the effectiveness of the drugs in treatment of insomnia symptoms. Previous meta-analyses have found that while benzodiazepines and Z-drugs reduced objective sleep latency with 10 and 13 min, respectively, and subjective sleep latency with 20 and 17 min respectively, melatonin reduced objective sleep latency with less than 6 min and subjective sleep latency with 11 min [36, 37]. This could suggest, that even as patients with insomnia symptoms still receive pharmacological treatment, the effect of the treatment may be less effective.

Due to the increased use of alternatives to benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, one could argue that the newer alternatives ought to be regulated by similar guidelines as benzodiazepines. For example, the incidence of low-dose quetiapine has increased over time, particular in the age-group above 80 years and in users without psychiatric or somatic comorbidity. Other studies have similarly shown an increase in off-label use of antipsychotics [25]. This increase might raise concerns regarding the potential side effects, as low-dose quetiapine has been associated with risk of diabetes [21], and the need for further regulations and closer monitoring of potential side-effects has been suggested [2]. For pregabalin, there has been reports of increased risk of fall accidents [38], as well as potential of addiction and even lethal overdosing [39], especially when used in adjacent to other psychiatric treatment, while the effects for insomnia is only documented among a selected group of patients with fibromyalgia [40]. For promethazine, lethal overdosing was the reason for the regulations in 2014, in order to limit the use. The explanation for the increase observed in our data after 2014 might be because it was previously sold over the counter. Also, lethal overdosing has been reported to increase among Swedish citizens [17]. This raises the question, whether the relatively high use of promethazine is favorable, at least clinicians should remain aware of the potential side effects and toxicity, especially when treating vulnerable individuals. Regarding melatonin, other studies have as mentioned before reported increases in incidence [31]; however. further studies need to be conducted to deduce the potential adverse effects and the risk of dependence.

The analysis of the comorbidities associated with use of sedative drugs revealed that depression was the most common comorbidity across drug-classes. Generally, a higher proportion of drug users was without somatic or psychiatric comorbidity in 2019 than 2000. A previous study from Switzerland which characterized users of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in 2018 showed a three times higher prevalence of multimorbidity compared to non-users [41]. One of the most notable observation in our study was the impact of the “Tryghedskasse” introduced in 2006. After this introduction, the individuals using hypnotic benzodiazepines were older (median age increased to 81 years) (Table 1), had more somatic comorbidities and dementia. Furthermore, the duration of medicine use became shorter and a larger proportion of hypnotic benzodiazepines was administered as injection (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Strengths and limitations

An advantage of this study is the use of nationwide population-based registers in a country with free access to health care; we had access to data from a large, unselected population. The Danish person identification numbers allowed us to link individual health data with different registries and thus obtain complete information for drug prescriptions and hospital contacts. The large size of the study guaranteed a relatively high number of users for all the specific medication types. Also, as all medication under study can only be obtained through a prescription, illicit use of the medication was assumed to be limited.

Several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, data on less severe disorders and symptoms treated in general practice were not available. Second, the Danish National Prescription Registry does not include medication dispensed at hospital departments, yet this concerns less than 1% of all prescribed medication. The register further does not include information on over-the-counter medication, which applies for some sedating antihistamines (and for promethazine before 2014). Finally, some sedating antidepressants such as trazodone and doxepin are not available in Denmark. Another limitation is that many of the included medications have other indications due to other effects, e.g. antidepressant or antipsychotic, and we do not always know that the indication for the medication is sedation. This is especially the case for olanzapine, pregabalin, mianserin/mirtazapine and promethazine. However, for all drugs except hypnotic benzodiazepines there was a tendency towards a higher prevalence of users without any other psychiatric medication/diagnosis (Table 1), which might suggest a change in prescription patterns. Regarding duration index calculation, we used it as a proxy for treatment duration [28]. The underlying assumption in the calculation of point-prevalence is that prevalence is not too high, and incidence is reasonably stable within the time window [28]. Further assumptions is that prevalence and incidence rates of drug use are at equilibrium [28], but for the new introduced drugs, it is hard to believe that the equilibrium is fulfilled, as the incidence rapidly changed in the first few years. However, we showed our calculations of duration index matched with using a different method, where DDD was used as a proxy for point-prevalence [27] (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Finally, information on most comorbidities was based on diagnosis from hospital registers, which may not include the milder cases of the diseases treated in primary care only. This could, however, not explain the surprising decline in the prevalence of many somatic diseases over time.

Conclusions

This nationwide drug utilization study showed that the use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs declined gradually from 2000 through 2019, whereas melatonin, promethazine, low-dose quetiapine and pregabalin increased in use. Our results indicate that the different regulations have influenced prescription practice toward more restrictive use of Z-drugs and benzodiazepines; however, for hypnotic benzodiazepines’ prescriptions have increased after the introduction of palliative care. Notably, however, we also observed a shift towards a higher proportion of sedative drug users without somatic or psychiatric comorbidity.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

References

Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C et al (2017) European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res 26:675–700

Modesto-Lowe V, Harabasz AK, Walker SA (2021) Quetiapine for primary insomnia: consider the risks. Cleve Clin J Med 88:286–294

Lader M (1991) History of benzodiazepine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat 8:53–59

Schmitz A (2016) Benzodiazepine use, misuse, and abuse: a review. Ment Health Clin 6:120–126

Gunja N (2013) The clinical and forensic toxicology of Z-drugs. J Med Toxicol 9:155–162

Marsden J, White M, Annand F et al (2019) Medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal: a mixed-methods public health review and national database study in England. Lancet Psychiatry 6:935–950

Schifano F, Chiappini S, Corkery JM et al (2019) An insight into Z-drug abuse and dependence: an examination of reports to the european medicines agency database of suspected adverse drug reactions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 22:270–277

Kurko TAT, Saastamoinen LK, Tähkäpää S et al (2015) Long-term use of benzodiazepines: definitions, prevalence and usage patterns—a systematic review of register-based studies. Eur Psychiatry 30:1037–1047

Janhsen K, Roser P, Hoffmann K (2015) The problems of long-term treatment with benzodiazepines and related substances. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int 112:1–7

Kripke DF, Langer RD, Kline LE (2012) Hypnotics’ association with mortality or cancer: a matched cohort study. BMJ Open 2:e000850

Crowe SF, Stranks EK (2018) The residual medium and long-term cognitive effects of benzodiazepine use: an updated meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 33:901–911

Andersen LPH, Gögenur I, Rosenberg J et al (2016) The safety of melatonin in humans. Clin Drug Investig 36:169–175

Schwartz TL, Stahl SM (2011) Treatment strategies for dosing the second generation antipsychotics. CNS Neurosci Ther 17:110–117

Højlund M, Pottegård A, Johnsen E et al (2019) Trends in utilization and dosing of antipsychotic drugs in Scandinavia: comparison of 2006 and 2016. Br J Clin Pharmacol 85:1598–1606

Kamphuis J, Taxis K, Schuiling-Veninga CCM et al (2015) Off-label prescriptions of low-dose quetiapine and mirtazapine for insomnia in The Netherlands. J Clin Psychopharmacol 35:468–470

Di Iorio G, Matarazzo I, Di Tizio L et al (2013) Treatment-resistant insomnia treated with pregabalin. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 17:1552–1554

Höjer J, Tellerup M (2018) Renässans för Lergigan med kraftig ökning av intoxikationsfall. Läkartidningen 115:E9EZ

Lægemiddelstyrelsen (2014) Antihistaminet promethazin (Phernergan) bliver receptpligtigt. https://laegemiddelstyrelsen.dk/da/nyheder/2014/antihistaminet-promethazin-phenergan-mfl-bliver-receptpligtigt/

Pedersen CB, Gotzsche H, Moller JO et al (2006) The Danish civil registration system. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull 53:441–9

Pottegård A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H et al (2017) Data resource profile: the Danish national prescription registry. Int J Epidemiol 46:798–798f

Højlund M, Lund LC, Andersen K et al (2021) Association of low-dose quetiapine and diabetes. JAMA Netw Open 4:e213209

Alvim MM, Cruz DT, Vieira MT et al (2017) Prevalence of and factors associated with benzodiazepine use in community-resident elderly persons. Rev Bras Geriatr E Gerontol 20:463–473

Kassam A, Patten SB (2006) Hypnotic use in a population-based sample of over thirty-five thousand interviewed Canadians. Popul Health Metr 4:15

Kuo C-L, Chien I-C, Lin C-H (2022) Trends, correlates, and disease patterns of sedative-hypnotic use among elderly persons in Taiwan. BMC Psychiatry 22:316

Højlund M, Andersen JH, Andersen K et al (2021) Use of antipsychotics in Denmark 1997–2018: a nation-wide drug utilisation study with focus on off-label use and associated diagnoses. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 30:e28

Evoy KE, Sadrameli S, Contreras J et al (2021) Abuse and misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: a systematic review update. Drugs 81:125–156

Methods to analyse medicine utilization and expenditure to support pharmaceutical policy implementation. WHO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274282/9789241514040-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hallas J, Gaist D, Bjerrum L (1997) The waiting time distribution as a graphical approach to epidemiologic measures of drug utilization. Epidemiology 8:666

Cadogan CA, Ryan C, Cahir C et al (2018) Benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescribing in Ireland: analysis of national prescribing trends from 2005 to 2015. Br J Clin Pharmacol 84:1354–1363

Okui T, Park J, Hirata A et al (2021) Trends in the prescription of benzodiazepine receptor agonists from 2009 to 2020: a retrospective study using electronic healthcare record data of a university hospital in Japan. Healthc Basel Switz 9:1724

Begum M, Gonzalez-Chica D, Bernardo C et al (2021) Trends in the prescription of drugs used for insomnia: an open-cohort study in Australian general practice, 2011–2018. Br J Gen Pract 71:e877–e886

Wesselhoeft R, Rasmussen L, Jensen PB et al (2021) Use of hypnotic drugs among children, adolescents, and young adults in Scandinavia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 144:100–112

Frase L, Nissen C, Riemann D et al (2018) Making sleep easier: pharmacological interventions for insomnia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 19:1465–1473

Carpenter JK, Andrews LA, Witcraft SM et al (2018) Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety 35:502–514

Jørgensen M, Videbech P, Osler M (2017) Benzodiazepiner har fortsat en plads i moderne psykiatrisk behandling. Ugeskr Laeger 179:2133–2137

Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH (2013) Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS ONE 8:e63773

Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C et al (2007) The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med 22:1335–1350

Mukai R, Hasegawa S, Umetsu R et al (2019) Evaluation of pregabalin-induced adverse events related to falls using the FDA adverse event reporting system and Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report databases. J Clin Pharm Ther 44:285–291

Bonnet U, Scherbaum N (2017) How addictive are gabapentin and pregabalin? A systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 27:1185–1215

Russell IJ, Crofford LJ, Leon T et al (2009) The effects of pregabalin on sleep disturbance symptoms among individuals with fibromyalgia syndrome. Sleep Med 10:604–610

Landolt S, Rosemann T, Blozik E et al (2021) Benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in Switzerland: prevalence, prescription patterns and association with adverse healthcare outcomes. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 17:1021–1034

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenqvist, T.W., Osler, M., Wium-Andersen, M.K. et al. Sedative drug-use in Denmark, 2000 to 2019: a nationwide drug utilization study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 1493–1502 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02409-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02409-5