Abstract

Purpose

While supported employment (SE) programs for people with mental illness have demonstrated their superiority in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses, little is known about the effectiveness of non-trial routine programs. The primary objective of this study was to estimate a pooled competitive employment rate of non-trial SE programs by means of a meta-analysis. A secondary objective was to compare this result to competitive employment rates of SE programs in RCTs, prevocational training programs in RCTs and in routine implementation.

Methods

A systematic review and a random-effects meta-analysis of proportions were conducted. Quality assessment was provided. Moderator analyses by subgroup comparisons were conducted.

Results

Results from 28 samples were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled competitive employment rate for SE routine programs was 0.43 (95% CI 0.37–0.50). The pooled competitive employment rates for comparison conditions were: SE programs in RCTs: 0.50 (95% CI 0.43–0.56); prevocational programs in RCTs: 0.22 (95% CI 0.16–0.28); prevocational programs in routine programs: 0.17 (95% CI 0.11–0.23). SE routine studies conducted prior to 2008 showed a significantly higher competitive employment rate.

Conclusion

SE routine programs lose only little effectiveness compared to SE programs from RCTs but are much more successful in reintegrating participants into the competitive labor market than prevocational programs. Labor market conditions have to be taken into account when evaluating SE programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In occupational rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness (SMI), supported employment (SE) programs in general and Individual Placement and Support (IPS) programs in particular have demonstrated superiority in a range of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). These trials usually compared SE-interventions to traditional prevocational training or to transition employment. Recent comparative meta-analyses have estimated that the superiority of SE against traditional programs in trials is more than double [1, 2].

While the trial results are very clear, routine implementation of SE in mental health care remains a challenge. Financing problems and resistance from the traditional prevocational training lobby have meant that many people with SMI do not receive SE-support although many of them aim at being included in competitive employment [3]. So far, SE-routine implementation has not received the same attention as trials and reviews of SE. This is unfortunate as routine implementation and its probable demonstrated effectiveness might be an additional point in order to advance SE within the psychiatric rehabilitation community.

In terms of psychiatric care, routine implementation results are at least as important as trial results. As is known since Cochrane’s elaboration on this issue, trial efficacy does not necessarily lead to effectiveness in real world settings [4]. Research on pharmacological phase IV studies has shown that effectiveness in community settings is usually associated with lower outcomes compared to trial results [5]. Reasons for this are less strict inclusion criteria, high rates of comorbidity, less motivated staff or other reasons that may lead to reduced service quality.

Our main goal with this study is to gather evidence on the effectiveness of routine implementation of SE programs by conducting a meta-analysis. Since many of the published studies do not utilize comparisons to non-SE programs, we cannot use direct comparative meta-analysis methodologies. Instead we will use a meta-analysis of proportions that will provide us with a pooled rate of effectiveness (details are provided in the “Methods” section).

Our secondary goal is to compare routine results with trial results of SE in order to find out the loss of efficacy following the implementation in the field. To achieve this goal, we will compare the pooled SE-routine competitive employment rates with pooled rates that will be derived by meta-analyses of proportions from studies that have been included in the most recent systematic reviews on supported employment.

Two previous US projects have endorsed quarterly benchmark rates for SE-programs. An early attempt by Gold et al. recommended “reasonably attainable employment rates” of 25 to 35% [6]. A later publication by Becker et al. proposed a minimum standard of 31%; established programs should reach 41%, while highly performing programs should reach 50% competitive employment [7]. These recommendations, derived from outcome data of the IPS Learning Community [8], were a bit lower than previous recommendations (33%, 45%, and 57%) due to the consequences of the economic recession in the US [9]. Quarterly rates are lower than cumulative rates that are used for research purposes as in this paper.

We know of only one previous attempt at deriving an overall competitive employment rate across several studies. Bond et al. have utilized means and medians from pooled IPS and control group samples that were included in RCTs [10]. By averaging across studies, this approach yielded a mean competitive employment rate of 58.9% (median 63.6%) for IPS programs. Control conditions yielded a mean competitive employment rate of 23.2% (median 26.0%). This approach has the disadvantage of not accounting for the heterogeneity of studies and of applying an equal weighting to any study that will probably lead to less precise estimates. Heterogeneity has to be assumed as the labor regulations differ highly across countries and as the labor market conditions will vary due to unemployment rates. Meta-analytical approaches can account for heterogeneity in general and will provide additional uncertainty estimates for the pooled rates (i.e. confidence intervals).

Methods

We have conducted a systematic review which included publications that report on competitive employment rates from SE-programs for people with mental illness running as routine services. Supported employment is commonly defined as “…a direct service with multiple components that provides a person with a mental or substance use disorder, for whom employment is difficult to secure, with specialized assistance in choosing, acquiring, and maintaining competitive employment. Supported employment services may include rapid job search, integration of rehabilitation and mental health services, job development, benefits counseling, and individualized follow-along supports that are necessary to sustain employment” [11].

We searched the following databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL (Cumulative Index on Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and used Google Scholar and reference lists for additional searches. The search term for PubMed was “(IPS OR “Individual Placement and Support” OR “supported employment”) AND (mental OR psychiatr*) AND (implement* OR evaluat* OR routine) NOT (RCT [TI] OR trial [TI])”. Search terms in other databases were adapted accordingly. Data or follow-up data from randomized controlled trials were explicitly excluded.

The retrieved publications were processed according to the PRISMA scheme (see Figure 1, Electronic Supplementary Material). Both authors independently carried out full-text reading for eligibility in further analyses and quality assessment. Assessment differences were solved in consensus meetings. For quality assessment we developed a five-item instrument that covered the following topics and used 1/0 coding for each item: SE as the main focus of the publication, appropriate sampling, sample size 50 plus, appropriate study details, response rate 70% plus. All publications with a score of three or higher were included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction for meta-analysis encompassed the following items: authors, publication year, study year [in case of not reporting the study year we imputed the year with publication year minus 5 (mean difference 4.975 years, median difference: 5 years)], country of study location, application of IPS methodology, IPS fidelity rating (where available), percentage of participants with schizophrenia/psychosis, follow-up period. Specifically for meta-analysis, we extracted the sample size and the absolute number of participants who achieved competitive employment. Competitive employment means that an individual works in the regular labour market and is compensated at or above the minimum wage or otherwise prevailing wages for at least 1 day [2]. In cases where only percentages were reported, we calculated the absolute numbers.

Meta-analysis of proportions was used for quantitative analysis. This technique is common for prevalence or incidence meta-analyses and is derived from effect size estimation [12, 13]. Results are reported as pooled proportions with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). In order to compare the employment rate of SE-routine programs with those of trials, we searched two recent meta-analyses for intervention studies and retrieved the publications [1, 2]. We did not search for further studies that were not included in those meta-analyses.

Furthermore, we compared the pooled competitive employment rate of SE-routine programs with competitive employment rates of conventional occupational programs that commonly encompass prevocational training and/or transitional programs (PVT programs hereafter). We used comparative data from those studies that provided direct comparisons of SE with PVT and those studies that served as comparison interventions in the meta-analyses by Modini et al. and by Suijkerbuik et al. [1, 2]. Again, we did not search for further studies. As SE-programs started in the 1980s we excluded studies published before 1990.

We used the ‘metaprop’-function from the ‘meta’-Package (version 4.9-0) [14, 15], R Statistical Software (version 3.4.3) [16], to conduct all quantitative analyses. As we assumed relevant heterogeneity, we utilized a random-effects model with a Freeman–Tukey arcsine transformation to stabilize the variances and with a Hartung–Knapp adjustment for estimating the between-study variance [17, 18]. The ‘forest’-function was used for the graphical display of results. Publication bias was assessed by a modified funnel plot that used the log odds against the study sample size rather than the commonly used inverse of standard error [19].

Results

Information from 34 publications representing 35 samples was included in the qualitative review. Five publications/samples were excluded after quality assessment and information from 30 samples was used for meta-analysis (see details in Table 1); 14 samples were from the United States. The other samples were from the United Kingdom (4), Australia (3), New Zealand (3), Canada (2) and one each from Hong Kong, Sweden, Netherlands and Switzerland. Sample sizes were heterogeneous between 21 and 3474. Overall, the included studies represented 8834 participants.

The pooled proportion of competitive employment in SE routine programs was 0.43 (95% CI 0.37–0.50, see Fig. 1). SE programs assessed in trial studies showed a pooled proportion of 0.50 (95% CI 0.43–0.56). PVT routine programs revealed a pooled proportion of 0.17 (95% CI 0.11–0.23) and PVT programs evaluated in trials showed a pooled proportion of 0.22 (95% CI 0.16–0.28), indicating that SE routine programs yielded a significantly higher competitive employment rate than PVT routine programs and PVT RCT programs (forest plots of the SE RCTs and the PVT studies are provided in Figures 2–4, Electronic Supplementary Material). Study heterogeneity in the SE routine program analysis was high (I2 = 96%, τ2 = 0.0221, p < 0.01). We found no asymmetry in the modified funnel plot, i.e. we found no relevant publication bias (see Figure 5, Electronic Supplementary Material).

Forest plot: supported employment programs—routine programs. Events number of study participants in competitive employment, Total sample size, 95% CI 95% confidence interval; Heterogeneity indicators: I2 percentage of variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance, τ2 estimate of the variance of the true effect size, p probability value/significance

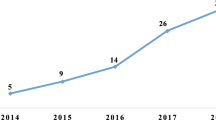

We conducted subgroup comparisons within the SE routine program samples. The following comparisons revealed no differences in terms of overlapping confidence intervals: country of origin (US vs. non-US), IPS Fidelity Rating (good, fair, not reported, no IPS), follow-up period (up to 12 months, 13–24 months, more than 24 months), percentage of participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia/psychosis (up to 50%, 51–70%, more than 70%). We found only one indicator showing a significant difference concerning whether the study had been conducted (not published) prior to 2008 or later. Pre-2008 studies revealed a much higher competitive employment rate than those from 2008 onwards [0.49 (95% CI 0.42–0.56) vs. 0.30 (95% CI 0.22–0.40)]. To check the validity of the results, we performed the same analyses on the SE trial sample and found the same pattern. Pre-2008 studies reported a much higher competitive employment rate than those conducted later [0.54 (95% CI 0.46–0.62) vs. 0.37 (95% CI 0.30–0.43)] with non-overlapping confidence intervals. When excluding US-trials in order to control for possible lower employment rates in other regions, we found the same tendency, although the intervals were overlapping due to fewer studies in the analysis. Again, all other subgroup comparisons revealed no such differences. Finally, we conducted the same analyses on the PVT RCT and routine samples, excluding the IPS variable. No differences emerged.

Discussion

We have conducted a meta-analysis of proportions on data from publications about SE routine implementation programs. Our results can be summarized as follows: SE routine programs were only slightly less effective than SE programs evaluated in RCTs. SE routine programs were significantly more effective than PVT programs both in trials and in routine implementation studies. Subgroup comparisons in SE routine and in SE RCT samples revealed a large effectiveness difference between studies conducted prior to 2008 and from 2008 onwards. No such difference was found in the PVT samples. The application of meta-analytical methods has a provided lower competitive employment rate for SE RCT programs compared to conventional summarizing methods. While Bond et al. found a mean rate of 58.9% in SE trial studies [10], our analysis yielded a pooled proportion of 50%.

Depending on temporal labor market conditions, SE routine programs may be expected to reach a competitive employment rate between 40 and 50%. Our results confirm the US-related recommendations by Becker and colleagues [7, 9] also for non-US regions. It is an important implication of our study that SE can be similarly successful in routine implementation under labor market conditions that are different (i.e. usually more regulated) from those in the US. Labor market regulations are known to have a significant impact on the SE competitive employment rates as a recent meta-regression has demonstrated [49]. That study found less protective approaches and less generous disability benefits to be predictive of higher competitive employment rates (relative to PVT).

Another important implication is that evaluations of SE programs have to take into account the economic conditions at that time and in that region. We found that the pooled competitive employment rate dropped 20% during the economic recession years. As recent European and US studies suggest, labor market developments during the economic recession have had a tremendous negative effect on the employment rates of people with disabilities and of people with mental illness in particular [50, 51]. US data also suggest that these developments had negative effects on vocational rehabilitation in general [52], while a recent meta-regression found no significant effects of the national unemployment rate on competitive employment in SE programs [49].

Limitations

The most important limitation that is common with data collection from routine programs in health care is the data quality. We assume that the data quality standards of the included studies were lower than those in RCTs. Also, in many cases we do not have enough information on the service quality of routine programs. These limitations, however, need to be balanced against the much higher overall number of participants in the routine programs. Whether routine programs are to be regarded as inferior or superior in terms of validity is a matter of perspective. While RCTs provide a better internal validity due to strict inclusion criteria, routine programs are expected to provide a better external validity.

Conclusions

Several conclusions emerge from our study. First, SE routine programs hold up to the expectations from the trials. There is only a small loss of effectiveness when implementing routine programs compared to RCTs. Second, the difference of competitive employment rates between SE and PVT programs remains as large as in the trials. Third, and most important, recent economic conditions seem to make it more difficult than in previous decades to reach high competitive employment rates even with evidence-based interventions such as SE. It remains to be seen whether the success rates will return to previous levels in the current economic climate in which we see a large decline in unemployment in western economies.

References

Modini M, Tan L, Brinchmann B, Wang MJ, Killackey E, Glozier N, Mykletun A, Harvey SB (2016) Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis of the international evidence. Br J Psychiatry 209(1):14–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.165092

Suijkerbuijk YB, Schaafsma FG, van Mechelen JC, Ojajarvi A, Corbiere M, Anema JR (2017) Interventions for obtaining and maintaining employment in adults with severe mental illness, a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD011867. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011867.pub2

Johnson-Kwochka A, Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, Greene MA (2017) Prevalence and quality of individual placement and support (IPS) supported employment in the United States. Adm Policy Ment Health 44(3):311–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0787-5

Cochrane AL (1972) Effectiveness and efficiency: random reflections on health services. Nuffield Trust, London

Smith PG, Morrow RH, DA R (eds) (2015) Field trials of health interventions: a toolbox, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gold PB, Macias C, Barreira PJ, Tepper M, Frey J (2010) Viability of using employment rates from randomized trials as benchmarks for supported employment program performance. Adm Policy Ment Health 37(5):427–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0258-3

Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR (2014) The IPS supported employment learning collaborative. Psychiatr Rehabil J 37(2):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000044

Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR, Noel VA (2016) The IPS learning community: a longitudinal study of sustainment, quality, and outcome. Psychiatr Serv 67(8):864–869. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500301

Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR (2011) Benchmark outcomes in supported employment. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 14:230–236

Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR (2012) Generalizability of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment outside the US. World Psychiatry 11(1):32–39

Marshall T, Goldberg RW, Braude L, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, George P, Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014) Supported employment: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv 65(1):16–23. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300262

Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T (2013) Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health 67(11):974–978. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-203104

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR (2009) Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley, Chichester

Polanin JR, Hennessy EA, Tanner-Smith ET (2017) A review of meta-analysis packages in R. J Educ Behav Stat 42:206–242

Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G (2015) Meta-analysis with R. Springer, Cham

R Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Hartung J, Knapp G (2001) A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med 20(24):3875–3889

IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF (2014) The Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian–Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-25

Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ (2014) In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 67(8):897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003

Anthony WA, Brown MA, Rogers ES, Derringer S (1999) A supported living/supported employment program for reducing the number of people in institutions. Psychiatr Rehabil J 23:57–61

Bailey EL, Ricketts SK, Becker DR, Xie H, Drake RE (1998) Do long-term day treatment clients benefit from supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J 22:24–29

Becker DR, Bond GR, McCarthy D, Thompson D, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Drake RE (2001) Converting day treatment centers to supported employment programs in Rhode Island. Psychiatr Serv 52(3):351–357. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.351

Beimers D, Biegek DE, Guo S, Stevenson L (2010) Employment entry through supported employment: Influential factors for consumers with co-occurring mental and substance disorders. Best Pract Ment Health 6(2):85–102

Browne DJ, Stephenson A, Wright J, Waghorn G (2009) Developing high performing employment services for people with mental illness. Int J Ther Rehabil 16:502–511

Corbiere M, Lecomte T, Reinharz D, Kirsh B, Goering P, Menear M, Berbiche D, Genest K, Goldner EM (2017) Predictors of acquisition of competitive employment for people enrolled in supported employment programs. J Nerv Ment Dis 205(4):275–282. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000612

Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, Torrey WC, McHugo GJ, Wyzik PF (1994) Rehabilitative day treatment vs. supported employment: I. Vocational outcomes. Community Ment Health J 30(5):519–532

Dudley R, Nicholson M, Stott P, Spoors G (2014) Improving vocational outcomes of service users in an Early Intervention in Psychosis service. Early Interv Psychiatry 8(1):98–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12043

Ellison ML, Klodnick VV, Bond GR, Krzos IM, Kaiser SM, Fagan MA, Davis M (2015) Adapting supported employment for emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. J Behav Health Serv Res 42(2):206–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-014-9445-4

Fabian ES (1992) Longitudinal outcomes in supported employment: a survival analysis. Rehabil Psychol 37(1):23–35

Fabian ES (1992) Supported employment and the quality of life: does a job make a difference? Rehabil Counsel Bull 36(2):84–97

Favre C, Spagnoli D, Pomini V (2014) Dispositf de soutien à l’emploi pour patients psychiatriques: évaluation rétrospective. Swiss Arch Neurol Psychiatry 185:258–264

Furlong M, McCoy ML, Dincin J, Clay R, McClory K, Pavick D (2002) Jobs for people with the most severe psychiatric disorders: thresholds Bridge North pilot. Psychiatr Rehabil J 26(1):13–22

Henry AD, Hashemi L, Zhang J (2014) Evaluation of a statewide implementation of supported employment in Massachusetts. Psychiatr Rehabil J 37(4):284–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000097

Lucca AM, Henry AD, Banks S, Simon L, Page S (2004) Evaluation of an Individual Placement and Support model (IPS) program. Psychiatr Rehabil J 27(3):251–257

Major BS, Hinton MF, Flint A, Chalmers-Brown A, McLoughlin K, Johnson S (2010) Evidence of the effectiveness of a specialist vocational intervention following first episode psychosis: a naturalistic prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0034-4

Morris A, Waghorn G, Robson E, Moore L, Edwards E (2014) Implementation of evidence-based supported employment in regional Australia. Psychiatr Rehabil J 37(2):144–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000051

Nygren U, Markstrom U, Svensson B, Hansson L, Sandlund M (2011) Individual placement and support—a model to get employed for people with mental illness—the first Swedish report of outcomes. Scand J Caring Sci 25(3):591–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00869.x

Oldman J, Thomson L, Calsaferri K, Luke A, Bond GR (2005) A case report of the conversion of sheltered employment to evidence-based supported employment in Canada. Psychiatr Serv 56(11):1436–1440. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.11.1436

Porteous N, Waghorn G (2007) Implementing evidence-based employment services in New Zealand for young adults with psychosis: progress during the first five years. Br J Occup Ther 70:521–526

Rinaldi M, Perkins R (2007) Comparing employment outcomes for two vocational services: individual placement and support and non-integrated pre-vocational services in the UK. J Vocat Rehabil 27:21–27

Rinaldi M, Perkins R, McNeil K, Hickman N, Singh S (2010) The Individual Placement and Support approach to vocational rehabilitation for young people with first episode psychosis in the UK. J Ment Health 19:483–491

Rosenheck RA, Mares AS (2007) Implementation of supported employment for homeless veterans with psychiatric or addiction disorders: two-year outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 58(3):325–333. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.325

Shafer MS, Huang H-W (1995) The utilization of survival analyses to evaluate supported employment services. J Vocat Rehabil 5:103–115

van Erp NH, Giesen FB, van Weeghel J, Kroon H, Michon HW, Becker D, McHugo GJ, Drake RE (2007) A multisite study of implementing supported employment in the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv 58(11):1421–1426. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.11.1421

van Veggel R, Waghorn G, Dias S (2015) Implementing evidence-based suppported employment in Sussex for people with severe mental illness. Br J Occup Ther 78:286–294

Waghorn G, Dias S, Gladman B, Harris M (2015) Measuring what matters: effectiveness of implementing evidence-based supported employment for adults with severe mental illness. Int J Ther Rehabil 22:411–420

Williams PL, Lloyd C, Waghorn G, Machingura T (2015) Implementing evidence-based practices in supported employment on the Gold Coaist for people with severe mental illness. Aust Occup Ther J 62:315–326

Wong K, Chiu LP, Tang SW, Kan HK, Kong CL, Chu HW, Lo WM, Sin YM, Chiu SN (2000) Vocational outcomes of individuals with psychiatric disabilities participating in a supported competitive employment program. Work 14(3):247–255

Metcalfe JD, Drake RE, Bond GR (2018) Economic, labor, and regulatory moderators of the effect of individual placement and support among people with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 44(1):22–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx132

Starace F, Mungai F, Sarti E, Addabbo T (2017) Self-reported unemployment status and recession: an analysis on the Italian population with and without mental health problems. PLoS One 12(4):e0174135. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174135

Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M, McCrone P, Thornicroft G, Mojtabai R (2013) The mental health consequences of the recession: economic hardship and employment of people with mental health problems in 27 European countries. PLoS One 8(7):e69792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069792

Chan JY, Wang CC, Ditchman N, K JH, Pete J, Chan F, Dries B (2014) State unemployment rates and vocational rehabilitation outcomes: a multilevel analysis. Rehabil Counsel Bull 57:209–218

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richter, D., Hoffmann, H. Effectiveness of supported employment in non-trial routine implementation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54, 525–531 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1577-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1577-z