Abstract

Purpose

Rates of hospital-treated self-harm are highest among young people. The current study examined trends in rates of self-harm among young people in Ireland over a 10-year period, as well as trends in self-harm methods.

Methods

Data from the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland on presentations to hospital emergency departments (EDs) following self-harm by those aged 10–24 years during the period 2007–2016 were included. We calculated annual self-harm rates per 100,000 by age, gender and method of self-harm. Poisson regression models were used to examine trends in rates of self-harm.

Results

The average person-based rate of self-harm among 10–24-year-olds was 318 per 100,000. Peak rates were observed among 15–19-year-old females (564 per 100,000) and 20–24-year-old males (448 per 100,000). Between 2007 and 2016, rates of self-harm increased by 22%, with increases most pronounced for females and those aged 10–14 years. There were marked increases in specific methods of self-harm, including those associated with high lethality.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that the age of onset of self-harm is decreasing. Increasing rates of self-harm, along with increases in highly lethal methods, indicate that targeted interventions in key transition stages for young people are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescent self-harm is a major public health problem [1], with a prevalence of approximately 10% based on community-based studies and with higher rates among girls than boys [2,3,4]. Internationally, hospital-treated self-harm has greatly increased in frequency among adolescents over the past 50 years. Potential factors contributing to this increase include greater availability of medication, increased stress, greater alcohol and drug consumption and social transmission of the behaviour, including via social media and websites with self-harm or suicide content [1, 5, 6]. Rates of hospital-treated self-harm have been reported to be strongly correlated with suicide rates in both males and females [7]. Due to high rates of self-harm and suicide among young people in Ireland, those aged 15–24 years have been identified as a priority group at whom to target approaches to reduce suicidal behaviour and improve mental health [8].

Self-cutting is the most common method of self-harm in adolescents in the community [3], while intentional drug overdose is the most common method in adolescent hospital-treated self-harm [9]. Examination of trends in methods of adolescent self-harm is of relevance to suicide prevention as risk of subsequent suicide has been shown to vary according to method of self-harm [10, 11]. It has also been reported that older adolescents and young adults are more likely to present with more severe acts of self-harm than children and younger adolescents [12]. A Belgian study of trends in self-harm method between 1997 and 2013 reported a proportional increase in the use of methods of self-harm such as hanging, jumping from heights and other violent methods [13].

Few studies have examined trends in rates of adolescent self-harm over time. One Canadian study of hospital presentations by those aged under 18 reported a decrease in rates in both girls and boys between 2002 and 2005, followed by a levelling off between 2006 and 2010 [14]. A similar study from England reported that rates in males aged 15–24 years decreased by 39% between 1996 and 2010 while rates among females of the same age decreased by 12.5% [15]. However, a UK study reported an increase in rates of presentation to primary care for self-harm between 2001 and 2013 among those aged 15–24 years, especially among females [16].

The aim of this research was to examine patterns of hospital-treated self-harm among young people aged 10–24 years in Ireland, using national data across a 10-year period. Specifically, the objectives were to identify age and gender-specific secular trends in rates of self-harm among young people between 2007 and 2016, to examine gender and age differences in relation to choice of self-harm method and to examine trends in methods over time.

Methods

Study population

This study used data from the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland. The Registry is a national surveillance system, which records information on self-harm presentations to all hospital emergency departments (EDs) in Ireland. All presentations made by children (10–14 years), adolescents (15–19 years) and young adults (20–24 years) during the 10-year period January 2007–December 2016 were included. There were 51 presentations made by young people aged under 10 years, representing 0.1% of all presentations. Due to small numbers, these presentations were excluded from the study.

The Registry uses an internationally-recognised definition of self-harm: “an act with non-fatal outcome in which an individual deliberately initiates a non-habitual behaviour, that without intervention from others will cause self-harm, or deliberately ingests a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognised therapeutic dosage, and which is aimed at realising changes that the person desires via the actual or expected physical consequences” [17]. Data are collected by independently trained data registration officers, using standardised operation procedures [18].

Data items

The Registry dataset includes the following relevant variables: gender, age, date and hour of presentation to hospital, method(s) of self-harm and alcohol involvement.

Methods of self-harm are recorded according to the Tenth Revision of the WHO’s International classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes for intentional injury (X60–X84) [19]. Where multiple methods of self-harm were used, all were recorded. In this classification, a distinction was made between intentional overdose of drugs and medicaments (X60–X64) and self-poisoning by chemicals and noxious substances(X66–X69). Self-harm acts involving alcohol were coded separately (X65). Alcohol involvement was defined as the intake of alcohol prior to or during the self-harm act. This was obtained through hospital case notes and, when available, from toxicology reports.

Statistical analyses

Annual self-harm rates per 100,000 by age and gender were calculated based on the number of persons aged 10–24 years who presented to hospital following self-harm in that calendar year. National Census population data and annual population estimates were obtained from the Irish Central Statistics Office. We calculated 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for these rates, using the normal approximation for the Poisson distribution. The 10-year rate was based on the sum of the number of persons who presented in each year and the sum of the annual population. We used Poisson regression models to assess changes in rates of self-harm from 2007 to 2016 by age and gender. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI), comparing the rate in the last year to the rate in the first year, are reported. Annual person-based rates of self-harm per 100,000 according to frequently used methods of self-harm were calculated in a similar way. Poisson regression models were also used to assess changes in rates of self-harm methods by age and gender, comparing the rate in the last year to the rate in the first year. Chi-square tests were employed to test age- and gender-specific differences in relation to the most frequently used methods of self-harm. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 12.

Results

Sample characteristics

Between 2007 and 2016, there were 38,225 presentations to hospital following self-harm by young people aged 10–24 years, involving 26,197 individuals. The majority of these presentations (n = 14,974; 57.2%) were made by females. A total of 2848 (7.5%) presentations were made by those aged 10–14 years, 17,345 (45.4%) by those aged 15–19 years and 18,032 (47.2%) by those aged 20–24 years.

Incidence of self-harm

For the 10-year period, the average person-based rate of hospital-treated self-harm was 318 per 100,000 (95% CI = 315–322) (Table 1). The female rate was 1.4 times higher than the male rate (368 vs. 271 per 100,000). Comparatively, self-harm was rare in 10–14-year-olds, in particular for boys. The peak rate for females was among 15–19-year-olds (564 per 100,000; 95% CI = 551–577) and for males was among 20–24-year-olds (448 per 100,000; 95% CI = 437–459). Rates of self-harm appeared to differ according to gender. Among 10–14-year-olds, the female rate was 3.3 times higher. However, this difference seemed to dissipate among older age groups, with the rate of self-harm among 20–24-year-olds similar for males and females.

Rates of self-harm, 2007–2016

Compared to 2007, the rate of self-harm among 10–24-year-olds was 22% higher in 2016 (IRR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.16–1.29). This increase was more pronounced among females (29%; IRR = 1.29, 95% C = 1.21–1.38) than males (14%; IRR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.05–1.23).

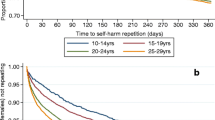

Trends in rates of self-harm by age group and gender are illustrated in Fig. 1. Across all ages, rates of self-harm increased between 2007 and 2016, with some fluctuation. The increase in the male rate of self-harm among 10–24-year-olds occurred in the early part of the study period (between 2008 and 2011), while the female rate increased from 2010 onwards. The full analysis of annual changes in rates of self-ham according to age and gender is detailed in Online Resource 1(a–d). Among 10–14-year-olds, the self-harm rate increased by 75% between 2007 and 2016 (IRR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.15–2.10). The male rate increased by 82% (IRR = 1.82, 95% CI = 1.26–2.63) while the female rate increased by 72% (IRR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.38–2.13) (Fig. 1a). There was a 25% overall increase for 15–19-year-olds (IRR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.16–1.35)—21% for males (IRR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.07–1.37) and 28% for females (IRR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.17–1.40) (Fig. 1b). For 20–24-year-olds, the rate increased by 39% (IRR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.29–1.50)—for males by 34% (IRR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.20–1.49) and for females by 44% (IRR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.30–1.60) (Fig. 1c).

Methods of self-harm

Considering frequently used methods of self-harm, almost two-thirds (65.2%; n = 24,920) of self-harm presentations involved an intentional drug overdose. Self-cutting was involved in 29.9% (n = 11,418) of presentations and attempted hanging in 6.6% (n = 2520) of presentations.

There was significant variation in method of self-harm according to gender. Intentional drug overdose was more common among females (70.3 vs. 58.4%; X2 = 587.6; p < 0.001), while self-cutting (32.0 vs. 28.3% X2 = 62.3; p < 0.001) and attempted hanging (10.4 vs. 3.8%; X2 = 657.9; p < 0.001) were more common among males.

There was some variation in methods of self-harm according to age (see Table 2). For both males and females, the proportion of self-harm presentations involving self-poisoning (by chemicals or noxious substances) was highest for 10–14-year-olds (4.7% for males, 3.6% for females). Intentional drug overdose was most common among 15–19-year-olds (58.7% for males, 71.6% for females). There was no variation in the proportion of presentations involving self-cutting for males, while self-cutting was most common among 10–14-year-old girls (32.6%). The proportion of presentations involving attempted hanging was highest among 10–14-year-old males (18.4%). However, this method did not vary according to age for females.

While rare as a sole method of self-harm, alcohol was present in just under one-third (n = 10,701; 28.0%) of self-harm presentations. Alcohol was more often consumed by males (32.8 vs. 24.4%; X2 = 325.2; p < 0.001) and among those aged 20–24 years for both males (37.5%) and females (33.1%).

Methods of self-harm, 2007–2016

There were changes in person-based rates of self-harm according to frequently used methods across the study period (see Table 3). Overall, there was an increase in the rate of individuals presenting with intentional drug overdose across the study population by 10% (IRR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.02–1.18). There was a 53% increase in self-cutting rates (IRR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.39–1.68). There was a twofold increase in the rate of attempted hanging (IRR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.62–2.47), while the rate of self-poisoning increased by 60% (IRR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.09–2.34).

The increase in intentional drug overdose was observed in 10–14-year-olds (IRR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.14–1.89) and 20–24-year-olds (IRR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.08–1.38). The increase in self-cutting was reflected across all ages for females (IRR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.75–2.29), whereas in males the increase was for 20–24-year-olds only (IRR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.11–1.62). Increases in self-poisonings were detected amongst 10–14-year-old females only, however this increase was based on relatively small numbers. Attempted hanging increased across males in all age groups (IRR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.38–2.26) and for 15–19-year-olds (IRR = 2.61, 95% CI = 1.37–4.95) and 20–24-year-old females (IRR = 4.20, 95% CI = 2.26–7.80).

Across all ages, there was a decrease in the proportion of presentations involving alcohol from 34 to 20%.

Discussion

This study focused on self-harm presentations to Irish hospitals over a 10-year period, involving 38,255 presentations by persons aged 10–24 years, 57% of whom were female. Whilst comparatively lower among 10–14-year-olds, high rates of self-harm were observed among older adolescents and young adults, with peak rates among females aged 15–19 years and among males aged 20–24 years. Between 2007 and 2016, the overall rate of self-harm among 10–24-year-olds increased by more than one-fifth, with significant increases observed among males in the 10–14 (+ 82%), 15–19 (+ 21%) and the 20–24 (+ 34%) year-old age-groups. For females, significant increases were found for 10–14-year-olds (+ 72%), 15–19-year-olds (+ 28%) and 20–24-year-olds (+ 44%). Across the 10-year period, there were increases in the rate of presentations due to intentional drug overdose, self-cutting and attempted hanging among young people.

The recent increases in self-harm rates among young people which we have reported are particularly striking when compared with overall trends in self-harm rates in Ireland. In the same time period, the overall male and female rates including all age groups showed smaller increases of 15 and 3%, respectively [9]. Our findings are similar to those of a UK study which reported an increase in rates of presentation to primary care for self-harm between 2001 and 2013 among those aged 15–24 years, especially among females [16]. A recent cohort study examining self-harm presentations to primary care in the UK reported a 68% increase in rates among girls aged 13–16 years between 2011 and 2014, which the authors note was mirrored by increases in suicide rates among young females in this period [20]. Increases were also reported among 17–19-year-old females between 2012 and 2014. Our findings of large increases across both genders and across all age groups of children, adolescents and young adults over a 10-year period differ from the findings of this study, where the most striking increase was among young female adolescents. Our findings also differ from a previous study based on hospital presentation data from Oxford, which examined an earlier time period, and reported reductions in rates of self-harm in young people—by 39% in males and 13% in females aged 15–24 years between 1996 and 2010 [15]. We did not formally examine the trend of increasing rates across the timepoints of the study period. However, the results show that for males the increase in the self-harm rate occurred between 2008 and 2011 while for females, the rate began to increase in 2010. An Irish study reported that the advent of economic recession in Ireland in 2007 was associated with an increase in rates of self-harm, and that the increase in women was greatest among 15–24-year-olds, while among males the increase was greatest among 25–44-year-olds [21]. A Canadian study also suggested that the economic recession led in part to the levelling off of rates of adolescent self-harm from 2007 onwards after a period of decline [14].

The most pronounced increases in rates of self-harm we observed were among children aged 10–14 years. The fact that rates of self-harm among females in childhood and early adolescence have almost doubled in the past 10 years is a particularly striking and worrying finding. Although self-harm in boys aged 10–14 years is rare, the sharp increase observed is also of concern. A systematic review of secular changes in mental health symptoms suggests that the impact of internalising symptoms is increasing in adolescent girls compared to previous cohorts, while results for boys were unclear [22]. This is a possible explanation for the increasing rates of self-harm, particularly among girls, given the strong associations between mental disorders such as depression and anxiety and self-harm in adolescents [1]. Our findings of increasing rates of self-harm in both sexes are, therefore, striking and warrant further in-depth investigation. As earlier age of onset of self-harm is associated with elevated risk of repeated self-harm [23], preventative interventions are urgently needed in this group. School-based universal mental health programmes have been found to be effective in preventing suicide attempts in young adolescents [24] and should be rolled out as a matter of priority.

Large increases in rates of self-harm among males and females in early adulthood are an additional cause for concern. The extension of time spent in education and the delay of marriage and parenthood that have occurred in developed countries in recent decades have led to the description of emerging adulthood as a separate stage. High rates of mental disorders during this life stage have been attributed to the instability of this period and, in Europe, to widespread unemployment and underemployment [25]. Although few previous studies have focused specifically on outcomes following self-harm in young adults, one large-scale Swedish study of young adults aged 18–24 found a 16-fold increased risk of suicide and a highly elevated risk of mental disorders at long-term follow-up [26]. Because this life stage has emerged relatively recently, mental health systems have not yet adapted to the developmental differences between emerging adults and those at different stages [27]. For young users of mental health services who transition from child and adolescent to adult services in the UK, the transition has been found to be poorly planned and negatively experienced by young people [28]. In Ireland, there is limited formal interaction between child and adult services [29] and many young people who reach the upper age limit of CAMHS services are not referred to adult services, despite ongoing needs [30]. Therefore, young adults may represent an unmet need in terms of clinical services and appropriate mental health promotion interventions.

In line with previous research, the most common methods involved in hospital-treated self-harm were intentional drug overdose and self-cutting [12, 31] with a minority involving methods associated with increased lethality. We found that self-cutting was more common among males, particularly among those aged 15 years and over. Self-cutting among males has previously been shown to be more often require extensive medical treatment [32]. The use of highly lethal self-harm methods is associated with increased risk of subsequent suicide [33]. As well as increases in rates of self-harm among young people, we detected trends in relation to method use across the study period. Rates of intentional drug overdose decreased during the study period as did the proportion of presentations involving alcohol. Rates of self-harm involving attempted hanging increased for both males and females. For females, rates of self-cutting and self-poisoning increased. These findings mirror those of a Belgian study which reported an increasing proportion of self-harm episodes involving self-injury (including cutting, hanging and drowning), and a decreasing proportion involving self-poisoning, which was particularly evident from the late 1990s to the end of the study period in 2013 [13]. This trend is of concern as self-cutting as a method of self-harm in children and adolescents conveys greater risk of repeated self-harm and of suicide than self-poisoning [23, 33]. Attempted hanging as a method of self-harm has also been reported to be associated with elevated risk of subsequent suicide, compared with other methods [34]. Research into fatal acts of hanging among young people suggests that internet-based social sites may facilitate the use of this method [35, 36].

We found that while overall rates of self-harm among children and adolescents were higher among females, this gender difference decreased with age, a trend which has been reported elsewhere [12, 37]. Suggested explanations for the differential age of onset of self-harm in boys and girls include differences in timing of pubertal development and earlier age of onset of mental disorders in girls [38]. The overall female rate of self-harm in all age-groups in Ireland in 2015 was 19% higher than the male rate, having been 37% higher 10 years previously [9]. This changing profile of self-harm appears to be driven by large increases in male rates in later adolescence. In the 20–24-year-old age group, the male rate now exceeds the female rate, a similar finding to that reported for 25–29-year-olds in Ireland [9]. In this regard, the gender paradox of higher suicide rates among males, despite lower prevalence of suicidal ideation and non-fatal suicidal behaviour [1] seems to no longer apply to young adults. These increases among young males from childhood onwards are of concern given the fact that men tend to use more lethal methods of self-harm and are less likely to engage with clinical services. Appropriate interventions are needed to prevent onset and repetition of self-harm in this group.

The increasing rates of self-harm among young people, as well as increases in methods of self-harm associated with higher lethality underline the need for interventions to reduce risk of repeat self-harm and suicide among this population. We were primarily interested in examining trends in rates of self-harm; however, further research to examine patterns of repeat self-harm according method is warranted. Previous research has reported that boys who have harmed themselves are at particularly high risk of suicide [39] therefore, increasing rates of self-harm among young males are of particular concern. Presentations to hospital as a result of self-harm provide an opportunity to provide appropriate referral and treatment options for those who have engaged in self-harm. It has previously been established that the majority of adolescent self-harm does not result in hospital attendance [40]. Therefore, opportunities to prevent suicidal behaviour in primary and post-primary settings as well as building resilience may be effective in reducing rates of self-harm in this group [1, 24]. In terms of treatments for self-harm among children and adolescents, there are indications of positive effects for therapeutic assessment, mentalisation and dialectical behaviour therapy. However, further evaluation using randomised controlled trials is warranted [41].

Strengths and limitations

We used data from the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland, which is a national system for the monitoring of hospital-treated self-harm. This has allowed us to examine national rates of self-harm among young people in Ireland and trends over a 10-year period. The Registry uses standardised definitions and inclusion criteria, and data are collected by trained data registration officers. Cases are only recorded if there was a clear intention to self-harm. In some circumstances this can be difficult to determine (for example, among children). Because of this, and due to small numbers, we limited our sample to 10–24-year-olds. It is likely that extent of alcohol involvement in self-harm presentations reported here is an underestimate, as it was dependent on the information being recorded by the attending clinician. We did not have access to more detailed clinical data regarding hospital presentations involving self-harm, such as psychiatric history, psychiatric diagnoses or levels of suicidal intent. Future research to explore how levels of suicidal intent vary according to demographic characteristics as well as method of self-harm would be important. Future research may also examine the clinical management and treatment pathways for young people attending hospital following self-harm. As studies using data on hospital presentations reflect trends in this help-seeking population only, further community-based research is needed to examine whether the trends we have observed reflect changing rates of self-harm in the general population.

Conclusion

Trends in rates of self-harm have been reported to be consistent with trends in suicide rates [1, 41]. Therefore, data on self-harm by young people constitute a sensitive indicator of suicide risk and incidence of mental ill-health in the population. Our findings in relation to the sharp increase in rates of self-harm for those aged 10–14 and 20–24 years are, therefore of particular concern. The increasing use of highly lethal methods of self-harm among young people is of great concern. Both universal prevention programmes and appropriate referral and treatment options are crucial to address the needs of young people in the key transition stages between childhood and adolescence and adolescence and adulthood.

References

Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC (2012) Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 379:2373–2382

Morey C, Corcoran P, Arensman E, Perry IJ (2008) The prevalence of self-reported deliberate self harm in Irish adolescents. BMC Public Health 8:79

Madge N, Hewitt A, Hawton K, de Wilde EJ, Corcoran P, Fekete S, van Heeringen K, De Leo D, Ystgaard M (2008) Deliberate self-harm within an international community sample of young people: comparative findings from the Child and Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:667–677

Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R (2002) Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ 325:1207–1211

Marchant A, Hawton K, Stewart A, Montgomery P, Singaravelu V, Lloyd K, Purdy N, Daine K, John A (2017) A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: the good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One 12:e0181722

Jacob N, Evans R, Scourfield J (2017) The influence of online images on self-harm: a qualitative study of young people aged 16–24. J Adolesc 60:140–147

Geulayov G, Kapur N, Turnbull P, Clements C, Waters K, Ness J, Townsend E, Hawton K (2016) Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England, 2000–2012. Findings from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England. BMJ Open 6:e010538

Department of Health (2015) Connecting for Life: Ireland’s National Strategy to reduce suicide (2015–2020). Department of Health, Dublin

Griffin E, Arensman E, Dillon CB, Corcoran P, Williamson E, Perry IJ (2017) National self-harm registry annual report 2016. National Suicide Research Foundation, Cork

Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, Ness J, Cooper J, Steeg S, Kapur N (2012) Premature death after self-harm: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet 380:1568–1574

Runeson B, Tidemalm D, Dahlin M, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N (2010) Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. BMJ 341:c3222

Diggins E, Kelley R, Cottrell D, House A, Owens D (2017) Age-related differences in self-harm presentations and subsequent management of adolescents and young adults at the emergency department. J Affect Disord 208:399–405

Vancayseele N, Portzky G, van Heeringen K (2016) Increase in self-injury as a method of self-harm in Ghent, Belgium: 1987–2013. PLoS One 11:e0156711

Rhodes AE, Bethell J, Carlisle C, Rosychuk RJ, Lu H, Newton A (2014) Time trends in suicide-related behaviours in girls and boys. Can J Psychiatry 59:152–159

Hawton K, Haw C, Casey D, Bale L, Brand F, Rutherford D (2015) Self-harm in Oxford, England: epidemiological and clinical trends, 1996–2010. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:695–704

Carr MJ, Ashcroft DM, Kontopantelis E, Awenat Y, Cooper J, Chew-Graham C, Kapur N, Webb RT (2016) The epidemiology of self-harm in a UK-wide primary care patient cohort, 2001–2013. BMC Psychiatry 16:53

Platt S, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, Schmidtke A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, De Leo D, Haring C, Lonnqvist J, Michel K et al (1992) Parasuicide in Europe: the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiatr Scand 85:97–104

Perry IJ, Corcoran P, Fitzgerald AP, Keeley HS, Reulbach U, Arensman E (2012) The incidence and repetition of hospital-treated deliberate self harm: findings from the world’s first national registry. PloS One 7:e31663

World Health Organization (2010) International classification of diseases and related health outcomes. 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. WHO, 2010. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#/X60-X84. Accessed 8 Feb 2018

Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, Kontopantelis E, Green J, Chew-Graham CA, Kapur N, Ashcroft DM (2017) Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ 359:j4351

Corcoran P, Griffin E, Arensman E, Fitzgerald AP, Perry IJ (2015) Impact of the economic recession and subsequent austerity on suicide and self-harm in Ireland: An interrupted time series analysis. Int J Epidemiol 44:969–977

Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, Hayatbakhsh R (2014) Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 48:606–616

Bennardi M, McMahon E, Corcoran P, Griffin E, Arensman E (2016) Risk of repeated self-harm and associated factors in children, adolescents and young adults. BMC Psychiatry 16:421

Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Wasserman C, Wall M, Eisenberg R, Hadlaczky G, Kelleher I, Sarchiapone M, Apter A, Balazs J et al (2015) School-based suicide prevention programmes: the SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 385:1536–1544

Arnett JJ, Zukauskiene R, Sugimura K (2014) The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 1:569–576

Beckman K, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Almqvist C, Runeson B, Dahlin M (2016) Mental illness and suicide after self-harm among young adults: long-term follow-up of self-harm patients, admitted to hospital care, in a national cohort. Psychol Med 46:3397–3405

Tanner JL, Arnett JJ (2013) Approaching young adult health and medicine from a developmental perspective. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 24:485–506

Singh SP, Paul M, Ford T, Kramer T, Weaver T, McLaren S, Hovish K, Islam Z, Belling R, White S (2010) Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: multiperspective study. Br J Psychiatry 197:305–312

McNamara N, McNicholas F, Ford T, Paul M, Gavin B, Coyne I, Cullen W, O’Connor K, Ramperti N, Dooley B et al (2014) Transition from child and adolescent to adult mental health services in the Republic of Ireland: an investigation of process and operational practice. Early Interv Psychiatry 8:291–297

McNicholas F, Adamson M, McNamara N, Gavin B, Paul M, Ford T, Barry S, Dooley B, Coyne I, Cullen W, Singh SP (2015) Who is in the transition gap? Transition from CAMHS to AMHS in the Republic of Ireland. Ir J Psychol Med 32:61–69

Hawton K, Bergen H, Kapur N, Cooper J, Steeg S, Ness J, Waters K (2012) Repetition of self-harm and suicide following self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the multicentre study of self-harm in England. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:1212–1219

Larkin C, Corcoran P, Perry I, Arensman E (2014) Severity of hospital-treated self-cutting and risk of future self-harm: a national registry study. J Ment Health 23:115–119

Lathi A, Harju A, Hakko H, Riala K, Räsänen P (2014) Suicide in children and young adolescents: a 25-year database on suicides from Northern Finland. J Psychiatr Res 58:123–128

Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, Ness J, Cooper J, Steeg S, Kapur N (2012) How do methods of non-fatal self-harm relate to eventual suicide? J Affect Disord 136:526–533

Rodway C, Tham SG, Ibrahim S, Turnbull P, Windfuhr K, Shaw J, Kapur N, Appleby L (2016) Suicide in children and young people in England: a consecutive case series. Lancet Psychiatry 3:751–759

Austin AE, van den Heuvel C, Byard RW (2011) Cluster hanging suicides in the young in South Australia. J Forensic Sci 56:1528–1530

Hawton K, Hall S, Simkin S, Bale L, Bond A, Codd S, Stewart A (2003) Deliberate self-harm in adolescents: a study of characteristics and trends in Oxford, 1990–2000. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 44:1191–1198

Rhodes AE, Boyle MH, Bridge JA, Sinyor M, Links PS, Tonmyr L et al (2014) Antecedents and sex/gender differences in youth suicidal behavior. World J Psychiatry 4(4):120–132. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i4.120

McMahon EM, Keeley H, Cannon M, Arensman E, Perry IJ, Clarke M, Chambers D, Corcoran P (2014) The iceberg of suicide and self-harm in Irish adolescents: a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49:1929–1935

Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, Arensman E, Gunnell D, Townsend E, van Heeringen K, Hazell P (2015) Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD012013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012013

Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, Cooper J, Kapur N (2010) Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England: 2000–2007. Br J Psychiatry 197:493–498

Acknowledgements

The National Self-Harm Registry Ireland is funded by the Irish Health Service Executive’s National Office for Suicide Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethics statement

The National Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health Medicine, Ireland granted ethical approval for the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Griffin, E., McMahon, E., McNicholas, F. et al. Increasing rates of self-harm among children, adolescents and young adults: a 10-year national registry study 2007–2016. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53, 663–671 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1522-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1522-1