Abstract

Background

Worldwide, approximately one in eight children or adolescents suffer from a mental disorder. The present study was designed to determine the cross-national prevalence of mental health problems in children aged 6–11 across seven European countries including Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey.

Methods

Data were collected on 7682 children for whom either parent- or teacher SDQ were completed.

Results

The present study provides country-specific normative banding for both parent- and teacher SDQ scores. Overall, 12.8 % of children have any probable disorder, with rates ranging from 15.5 % in Lithuania to 7.8 % in Italy, 3.8 % of children have a probable emotional disorder, 8.4 % probable conduct disorder, and 2.0 % probable hyperactivity/inattention. However, when adjusting for key sociodemographic variables and parental psychological distress, country of residence did not predict the odds of having any disorder. For specific disorders, however, country of residence does have an effect on the odds of presenting with mental health problems.

Conclusions

As normative data are key in the comparison of mental health status on an international level, the present data considerably advance the possibilities of future research. Furthermore, the findings underline the importance of controlling for a number of sociodemographic and parental variables when conducting international comparisons of child mental health. In addition, the findings suggest that efforts are needed locally to assist in the detection and prevention of parental psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A recent meta-analysis estimated the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents at 13.4 % (95 % CI 11.3–15.9) in a pooled sample of 87,742 youth reflecting 41 different studies [1]. Specifically, the estimated prevalence for any anxiety disorder is 6.5 %; any depressive disorder, 2.6 %; attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, 3.4 %; oppositional defiant disorder, 3.6 %; and conduct disorder, 2.1 % [1]. Mental health problems during childhood are associated with psychiatric disorders and functional impairment through adolescence and into adulthood [2, 3]. Child psychopathology also interferes with learning and is correlated with poor academic performance [4]. Considering the societal burden accompanying mental health problems, the European Union supports the development of standardized cross-national assessments of youth mental health within its member states. However, comparing child mental health status across countries or cultural groups raises important methodological issues.

First, obtaining comparable data can be done by applying the same instrument across a variety of cultures, which may cause difficulties related to translation or cultural relevance of assessment tools in specific cultural groups [5]. In addition, dimensional instruments to measure psychopathology such as the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [6, 7] or the as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [8] have been recommended over diagnostic assessments, as consistency in diagnostic accuracy may be even more difficult to obtain across a variety of cultures [9, 10]. Extensive research has been published on the reliable psychometric properties of the SDQ around the world and on its concordance with diagnostic interviews and referrals to mental health providers [11, 12]. While these findings might be interpreted as support for the use of universal cut-points, Goodman and collaborators [5] recently argued that population-specific norms should be applied in order for international comparisons to be valid. Normative banding provides cut-points that allow clinicians and researchers to identify youth within a normal of deviant range of a given score. While it is important to gather information on country-specific norms, recent reviews suggests that it may be even more relevant to consider countries as falling into three categories with low-, medium-, and high-scoring norms [13, 14].

Second, sampling methods applied across countries as well as the age range under investigation are also important to consider when comparing international data. Several studies have been conducted among 6- to 11-year olds. A recent meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of mental disorders in that age range at 12.36 % worldwide [1]. One cross-national study focused on children ages 7, 9, and 11 across Nordic countries using the parent-reported SDQ and yielded descriptive comparisons for two–three countries at a time within each child age group suggesting strong similarities between Norway, Denmark and Sweden [15]. Another study provided descriptive comparisons suggesting that parents in the UK tended to rate their children as having higher Total Difficulties scores as compared to parents in the US [16]. The Kidscreen study examined 15,945 adolescents with a mean age of 14.4 years across 13 countries relying on the adolescent self-reported SDQ, and applying the cut-points provided by the UK [17]. The study identified important differences in the prevalence of self-reported mental health problems suggesting that the UK had the highest prevalence of mental health problems, followed by the Czech Republic, France, Hungary and Greece [1]. Another large international study used the CBCL to examine children aged 6–11 across 12 regions including [9]. The latter cross-national comparison identified cultural variation in total problems scores with Puerto Rico and Sweden at the highest and lowest end of the spectrum, respectively. Finally, a large study compared parent-reported CBCL scores in youth aged 6–16 [18] and revealed that high scoring regions were Puerto Rico Portugal, Ethiopia, Greece, Lithuania, and Hong Kong while low scoring regions were mostly represented by Nordic or Asian countries (Japan, China, Sweden, Norway, Germany, and Iceland), consistent with prior findings [13]. Limitations of these studies, however, lie in the large differences in methodology across datasets including sampling procedures, time frames, specific informants [19], and the inability to test the effect of socioeconomic status may have contributed to the observed variation [9, 13].

The present study is a European Union-funded project designed to determine the cross-national prevalence of mental health problems in children aged 6–11 across seven European countries including Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey [20]. The study applied similar sampling methods in each country, used both parent- and teacher reports of child mental health, and collected extensive sociodemographic information, thus improving upon previous large cross-national studies of child mental health. Furthermore, the present study focuses on countries that fall within the middle-scoring groups previously identified, with the exception of Germany previously identified as a low-scoring country [13] based on data published in 1997 [21]. More recent works using the SDQ have shown that German normative data were similar to what has been obtained in the UK [22]. As a result, cross-national comparisons within this homogeneous group may contribute to the validity of cultural comparisons.

The specific objectives of the study are (1) to determine the country-specific range of SDQ scores within each country and provide parent and teacher banding, (2) to compare the prevalence of high Total Difficulties and probable mental disorders overall, and for boys and girls separately, and (3) to determine the sociodemographic characteristics associated with probable disorders as measured by the SDQ across Europe.

Methods

Participants and sampling

The School Children Mental Health Europe (SCMHE) study is a cross-sectional survey of European school children aged 6–11. The sample included data collected in 2010 in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey. Country-specific sampling procedures have been described elsewhere in detail [20]. First, approximately 45–50 schools were approached per country (a greater number of schools were approached in Germany and the Netherlands). Second, 48 children were then randomly selected in each school, except in the Netherlands, where a lesser number of schools participated and therefore entire classes were included, about 120 children per class. Parents received an informational letter and a consent form to be returned to the school. If the parents did not mail to the school a consent form stating their refusal to participate, the child was included. Children absent on the day of the survey were excluded. Among participating schools, between 50.5 % (Turkey) and 90.5 % (The Netherlands) selected children participated. Among the children participating in the study, and either parent or teacher SDQ reports (n = 7682) were available for 91.0 % of participants. Among them, both parent and teacher reports (n = 5670) were available for 73.8 % of the sample, parent only (n = 361) and teacher only (n = 1651) reports for 4.7 and 21.5 %, respectively, Within each country, except for Italy where it was not possible, data were weighted to adjust the probability of being selected considering the size of the school.

The present study focuses on parent- and teacher reports of child mental health status based on their completion of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire. The total sample size was 7682 overall, ranging from 757 in Italy to 1399 in the Netherlands with either teacher-reported or parent-reported outcomes.

Each country received approval of relevant ethical committees. Specific procedures were used in Germany and Turkey where such committees operate differently. In addition, each country provided authorizations from school authorities. In Bulgaria: The Deputy Minister of Education, Youth and Science of the Republic of Bulgaria; in Germany approval was obtained through landers: (a) Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, (b) State school authority, Luneburg, (c) Ministry of Education and Culture of Schleswig–Holstein country; in Lithuania: the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania; in the Netherlands: the Commission of Faculty Ethical Behavior Research; in Romania the Bucharest School Inspectorate General Municipal, and in Turkey: the Istanbul—directorate of National Education.

Materials

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

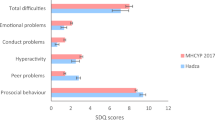

Child psychopathology was assessed using the parent- and teacher versions of the SDQ [6, 7]. The SDQ contains 25 questions. Each item is scored as ‘not true’, ‘somewhat true’ or ‘certainly true’. The questionnaire is divided into five subscales of five items each: Hyperactivity/Inattention, Emotional problems, Conduct problems, Peer problems and Prosocial behaviors. A Total Difficulties score is computed representing the sum of the first four subscales listed above (Emotional, Conduct, Hyperactivity-Inattention and Peer relationship problems). Additional questions are available in the SDQ to measure the functional impairment experienced by the children such as distress and interference in everyday life activities. The impairment data are used in conjunction with the SDQ scores in computerized algorithms described by Goodman [23]. The algorithms group parent- and teacher SDQ to define “unlikely”, “possible” or “probable” cases of any disorder, emotional problems, hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems. Each of these variables was recoded to represent absence (unlikely or possible) or presence (probable) of disorders.

Furthermore, a four-band categorization of SDQ scores has been recommended to reflect the distribution of scores in the population with the following breakdown based on the within-country percentile of scores: 0–80th percentile: ‘close to average’, 81–90th percentile ‘slightly raised’, 91–95th percentile: ‘high’ and 96–100th percentile ‘very high’ for all scales.

Parental psychological distress

Psychological distress in the previous 4 weeks was assessed using the 5-item Mental Health (MH-5) of the SF-36 Short Form [24]. This instrument has been validated in numerous languages and has been widely used [25]. The SF-36 has good construct validity, high internal consistency and high test–retest reliability and is strongly correlated with the GHQ-12 [26, 27].

Data analysis

Normative banding was based on the range of scores obtained on each scale for parent SDQ and for teacher SDQ for the four bands. Scores associated with the cumulative percentage the closest to 0–80th percentile, 81–90th percentile, 91–95th percentile, and 96–100th percentile. The distribution of high Total Difficulties for parent- and teacher SDQ, and the prevalence of probable disorders were examined with weighted frequency counts and Chi-square tests were used to identify differences in the distribution across countries. Lastly, a series of logistic regressions was performed predicting probable disorders, and adjusting for sociodemographic variables. Each country was entered into the model using the grand mean as a reference. All analyses were performed using SPSS v.20. Between-country comparisons were weighted to adjust for the size of the sample provided by each country. Weights were not applied in Italy as the data collected did not allow us to match children to a specific school. That being said, there was no significant variation in school size in Italy. As a consequence, the weight applied to Italy would likely have been inconsequential.

Results

Normative banding of parent-reported SDQ scores

Table 1 presents the range of parent SDQ scores associated with each of the four bands in each country along with normative data from the UK. Differences were observed in the scores associated with each band. The Netherlands had the cut-points the closest to UK norms for each of the scales. For Total Difficulties, the cut-points for the 80 % band differed across countries ranging from 0 to 9 in Italy to 0–16 in Lithuania.

Normative banding of teacher-reported SDQ scores

Table 2 presents the range of teacher SDQ scores associated with each of the four bands in each country. The banding across countries shared more similarities as compared to what was observed with the parent SDQ. For the Hyperactivity subscale, all countries had the same cut-points for the first band with scores from 0 to 5 with the exception of Italy (0–3) and Lithuania (0–6). All subscales displayed mild variation is scores associated with banding.

Distribution of children with high total difficulties (HTD) or probable disorder

Table 3 presents χ 2 tests comparing the prevalence of high total difficulties as evaluated by parents or teachers and probable disorders for each disorder across countries. Overall 15.3 % of the children have HTD according to the parents and a slightly higher percentage: 18.3 % according to the teachers with Lithuania, Turkey, Romania and Bulgaria displaying the highest rates and Italy displaying the lowest. Parent and teacher data appeared to be closer for girls than they were for boys. Indeed, these differences are due to the increased prevalence of externalizing disorders among boys as compared to girls, and to the greater likelihood of these disorders to be reported by teachers.

Overall, 12.8 % of children were identified as having at least one probable disorder, 8.4 % having a conduct disorder, 3.8 % an emotional disorder, and 2.0 % hyperactivity or inattention disorder. Lithuania (15.5 %), Germany (12.8 %), Romania (12.3 %), the Netherlands (11.9 %) and Bulgaria (11.2 %) had the highest prevalence of any disorder while Italy had the lowest (7.8 %).

Sociodemographic factors associated with probable mental disorders

Table 4 presents the adjusted odds ratios associated with probable disorders, using grand means as the reference in the determination of country ORs. When adjusting for all variables presented in the table, male gender (OR = 2.38), low maternal education level (OR = 1.49), single marital status (OR = 1.66), having two or three (OR = 1.34) or four or more children in the household (OR = 1.76), parental psychological distress (OR = 2.51) were all significantly associated with the probability of having any disorder. None of the seven countries exhibited a significant difference in the likelihood of presenting with any disorder.

There were, however, country effects when specific types of disorders were considered. For emotional disorders, the predictors were having a single (OR = 1.73) or inactive mother (OR = 1.70), parental psychological distress (OR = 2.59), and living in the Netherlands (OR = 1.80). Male gender (OR = 5.32), mothers under 35 (OR = 2.03) or between 35 and 40 years old (OR = 3.11) and psychological distress (OR = 4.01) were all associated with increased probability of hyperactivity or inattention disorder, as was living in the Netherlands (OR = 1.98), Germany (OR = 1.91) while living in Romania reduced the likelihood of the disorder (OR = 0.36). Conduct disorder was predicted by child male gender (OR = 3.40), lower education level, single mother (OR = 1.66), being raised in a household with four or more children (OR = 1.77) and parental psychological distress (OR = 2.23). When adjusting for the effects of sociodemographic characteristics and parental psychological distress, living in Germany increased the odds of conduct disorder (OR = 1.51) while living in Turkey decreased the odds (OR = 0.63).

Discussion

The present study provides normative banding for both for parent- and teacher-reported SDQ on large samples of children across Europe, offering normative cut-points for each country. Normative data is currently available for several countries on the SDQ website (http://www.sdqinfo.com), for parent and/or teacher SDQ scores. However, normative data are absent for most of the countries described in the present study including Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, the Netherlands and France. Normative data are available for Italy for the teacher SDQ regarding children aged 4–16 years and are provided for girls and boys, separately and by preschool, primary or secondary school status [28]. The present results are identical to the 96–100th percentile reported in girls in primary school for each of the subscales though not for the total difficulties. The present results are also similar though not identical to what was reported for primary school boys [28]. Furthermore, data derived from a nationally representative sample in Germany provided normative data for parent-reported SDQ in a sample of 930 children aged from 6 to 16 years [22] which are similar to what is reported here. Finally, normative data may help guide researchers and clinicians in identifying scores typically obtained in a given population. However, normative data is also subject to variation as a function of the prevalence of mental health concerns in that population.

When normative cut-points suggested by the author of the SDQ were applied, reflecting normative banding of SDQ scores in Great Britain, again, western European countries including Italy and the Netherlands displayed comparatively lower percentages of disordered children as compared to eastern European countries such as Lithuania as observed in a previous cross-national study [18], although Germany had the second highest percentage of children with conduct or hyperactivity disorders. However, it would be difficult to interpret these findings as true cross-national differences without evidence of the concurrent validity of the SDQ with more thorough clinical assessments within each country. The issue of the comparability of SDQ caseness indicators has recently been raised in a recent cross-national study among children 5–16 years old conducted on population samples from Yemen, Brazil, Britain, Norway, India, and Russia [5]. Furthermore, in two cross-national studies among adolescents who completed the self-reported version of the SDQ, it has been suggested that the SDQ might be sensitive to cultural differences [29, 30]. Nevertheless, data from a validation study associated with the present study carefully examined the ability of the parent- and teacher SDQ to correctly identify probable cases of disorder against the well-established Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) [31], a structured computerized interview designed to generate DSM-IV [32] psychiatric diagnoses on 5- to 17-year-old children and adolescents. The SDQ proved to be a satisfactory screening instrument for the detection of any mental disorder (AUC = 0.74, 95 % CI 0.69–0.78), and for externalizing disorders in particular (AUC = 0.80, 95 % CI 0.76–0.84), suggesting that it may be appropriate to use the SDQ as an indicator of the probable presence of externalizing disorders as each of the seven countries considered in the investigation obtained acceptable identification rates for these disorders, though the SDQ was only moderately able to detect internalizing disorders [33]. In addition, the great majority of countries considered in the present investigation fell within the middle-scoring countries in a recent review of studies using the CBCL to compare child mental health, thereby increasing their comparability [13].

Furthermore, cross-national comparisons should carefully consider the role of socio-economic variables in the prevalence of disorders considering the presence of high income and middle income countries [9]. Logistic regressions adjusting for the effect of a number of key socio-demographic variables yielded important findings pointing to the absence of country-specific effects on the probability of having any mental disorder. The strongest and most consistent predictor of disorder was parental psychological distress. Among the sociodemographic factors consistently associated with the probability of disorder was male gender, due to hyperactivity/inattention and conduct disorder while no gender differences were observed regarding internalizing disorders, which is consistent with previous research [9, 13, 22, 34] although a greater prevalence of internalizing disorders is found in adolescent girls as compared to boys [35]. In addition, living in Germany proved to be associated with increased odds of externalizing disorders, suggesting that variables not included in the model, such as familial interactions and parental attitudes may be responsible for the latter result. Future studies should investigate whether parenting behaviors vary across Europe and how they relate to prevalence estimates of child mental health problems.

In interpreting the findings, several limitations should be considered. First, school participation rates varied across countries. Participation from schools in Eastern Europe was easier to obtain than in Western Europe except for Italy, as the present study was part of a larger survey. However, because the decision to participate was administrative rather than personal, it is unclear whether this has biased the present findings. Second, in Italy it was not possible to determine weights for schools because we did not get the necessary information; however, the range of school size was not as large as in some of the country and comparisons of weighted and non-weighted results show no difference. Third, we limited analyses of probable disorders to the 62.7 % of cases (n = 5670) for whom both parent and teacher data were available. Finally, apart from Lithuania, none of the samples were representative of their country’s population.

The present cross-national study applied a uniform methodology in relatively large samples that allowed us to generate country-specific normative banding for both parent- and teacher SDQ scores, thus improving upon existing large cross-national studies. Normative data were not previously available for the majority of countries included in the study. As normative data are key in the comparison of mental health status on an international level, these data considerably advance the possibilities of future research. A second important finding suggested that when applying normative data from the UK, child mental health differs across the EU countries with the higher rates observed in Eastern countries as compared to Western countries. That being said, the observed differences were removed by adjusting for key sociodemographic variables such as parental psychological distress. The latter finding suggests that efforts are needed locally to assist in the detection and prevention of parental psychological distress.

References

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA (2015) Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):345–365

Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A (2003) Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:837–844

Belfer ML (2008) Child and adolescent mental disorders: the magnitude of the problem across the globe. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(3):226–236

Vander Stoep A, Weiss N, Saldanha E, Cheney D, Cohen P (2003) What proportion of failure to complete secondary school in the US population is attributable to adolescent psychiatric disorder? J Behav Health Serv Res 30(1):119–124

Goodman A, Heiervang E, Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Alyahri A, Patel V, Mullick MI, Slobodskaya H, dos Santos D, Goodman R (2012) Cross-national differences in questionnaires do not necessarily reflect comparable differences in disorder prevalence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(8):1321–1331. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0440-2

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(11):1337–1345. doi:10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

Achenbach T, Rescorla L (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: an integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Research Center for Children, Youth & Families, University of Vermont, Burlington

Crijnen AA, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC (1997) Comparisons of problems reported by parents of children in 12 cultures: total problems, externalizing, and internalizing. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(9):1269–1277

Bird HR (1996) Epidemiology of childhood disorders in a cross-cultural context. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 37(1):35–49

Achenbach TM, Becker A, Döpfner M, Heiervang E, Roessner V, Steinhausen HC, Rothenberger A (2008) Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(3):251–275

Goodman R, Renfrew D, Mullick M (2000) Predicting type of psychiatric disorder from strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) scores in child mental health clinics in London and Dhaka. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 9(2):129–134

Rescorla L, Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Begovac I, Chahed M, Drugli MB, Emerich DR, Fung DS, Haider M, Hansson K (2012) International epidemiology of child and adolescent psychopathology II: integration and applications of dimensional findings from 44 societies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(12):1273–1283 (e1278)

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Ivanova MY (2012) International epidemiology of child and adolescent psychopathology I: diagnoses, dimensions, and conceptual issues. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(12):1261–1272

Obel C, Heiervang E, Rodriguez A, Heyerdahl S, Smedje H, Sourander A, Guðmundsson ÓO, Clench-Aas J, Christensen E, Heian F (2004) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire in the Nordic countries. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 13(2):ii32–ii39

Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae DS, Simpson G, Koretz DS (2005) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: US normative data and psychometric properties. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44(6):557–564

Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Gosch A, Wille N (2008) Mental health of children and adolescents in 12 European countries—results from the European KIDSCREEN study. Clin Psychol Psychother 15(3):154–163

Rescorla L, Achenbach T, Ivanova MY, Dumenci L, Almqvist F, Bilenberg N, Bird H, Chen W, Dobrean A, Döpfner M (2007) Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 16 in 31 societies. J Emot Behav Disord 15(3):130–142

De Los Reyes A, Thomas SA, Goodman KL, Kundey SM (2013) Principles underlying the use of multiple informants’ reports. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 9:123–149

Kovess V, Carta MG, Pez O, Bitfoi A, Koç C, Goelitz D, Kuijpers R, Lesinskiene S, Mihova Z, Otten R (2015) The School Children Mental Health in Europe (SCMHE) project: design and first results. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health: CP & EMH 11 (Suppl 1 M7):113–123. doi:10.2174/1745017901511010113

Döpfner M, Plück J, Berner W, Fegert J, Huss M, Lenz K, Schmeck K, Lehmkuhl U, Poustka F, Lehmkuhl G (1997) Mental disturbances in children and adolescents in Germany. Results of a representative study: age, gender and rater effects. Zeitsch Kinder Jugendpsychiatrie Psychother 25(4):218–233

Woerner W, Becker A, Rothenberger A (2004) Normative data and scale properties of the German parent SDQ. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 13(2):ii3–ii10. doi:10.1007/s00787-004-2002-6

Goodman R (1999) The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(05):791–799

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30(6):473–483

Ware JE, Gandek B (1998) Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol 51(11):903–912

Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S (1994) SF-36 physical and mental component summary measures: a user’s manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

McCabe C, Thomas K, Brazier J, Coleman P (1996) Measuring the mental health status of a population: a comparison of the GHQ-12 and the SF-36 (MHI-5). Br J Psychiatry 169(4):516–521

Tobia V, Gabriele MA, Marzocchi GM (2011) Norme italiane dello Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Il comportamento dei bambini italiani valutato dai loro insegnanti. Disturb Attenzione Iperattività 6:167–174

Essau CA, Olaya B, Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous X, Pauli G, Gilvarry C, Bray D, O’callaghan J, Ollendick TH (2012) Psychometric properties of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire from five European countries. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 21(3):232–245

Stevanovic D, Urbán R, Atilola O, Vostanis P, Balhara YS, Avicenna M, Kandemir H, Knez R, Franic T, Petrov P (2015) Does the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—self report yield invariant measurements across different nations? Data from the International Child Mental Health Study Group. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 24(04):323–334

Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H (2000) The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41(05):645–655

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Husky M, Pez O, Bitfoi A, Carta M, Goelitz D, Kuijpers R, Koç C, Lesinskiene S, Mihova Z, Kovess-Masfety V (submitted) Psychometric properties of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire in children 5 to 12 across seven European countries

Shojaei T, Wazana A, Pitrou I, Kovess V (2009) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: validation study in French school-aged children and cross-cultural comparisons. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(9):740–747. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0489-8

Rescorla L, Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, Dumenci L, Almqvist F, Bilenberg N, Bird H, Broberg A, Dobrean A, Döpfner M (2007) Epidemiological comparisons of problems and positive qualities reported by adolescents in 24 countries. J Consult Clin Psychol 75(2):351

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Union, Grant number 2006336.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kovess-Masfety, V., Husky, M.M., Keyes, K. et al. Comparing the prevalence of mental health problems in children 6–11 across Europe. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 1093–1103 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1253-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1253-0