Abstract

Purpose

Low social support and small social network size have been associated with a variety of negative mental health outcomes, while their impact on mental health services use is less clear. To date, few studies have examined these associations in National Guard service members, where frequency of mental health problems is high, social support may come from military as well as other sources, and services use may be suboptimal.

Methods

Surveys were administered to 1448 recently returned National Guard members. Multivariable regression models assessed the associations between social support characteristics, probable mental health conditions, and service utilization.

Results

In bivariate analyses, large social network size, high social network diversity, high perceived social support, and high military unit support were each associated with lower likelihood of having a probable mental health condition (p < .001). In adjusted analyses, high perceived social support (OR .90, CI .88–.92) and high unit support (OR .96, CI .94–.97) continued to be significantly associated with lower likelihood of mental health conditions. Two social support measures were associated with lower likelihood of receiving mental health services in bivariate analyses, but were not significant in adjusted models.

Conclusions

General social support and military-specific support were robustly associated with reduced mental health symptoms in National Guard members. Policy makers, military leaders, and clinicians should attend to service members’ level of support from both the community and their units and continue efforts to bolster these supports. Other strategies, such as focused outreach, may be needed to bring National Guard members with need into mental health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social support can be conceptualized as the comfort or assistance received through contact with others [1]. Social support is robustly associated with mental and physical health outcomes across a variety of contexts and for a wide range of individuals [2–5]. For example, low social support is associated with greater mortality, suicidal ideation, dementia, and depression [2–5]. Reservists and National Guard service members report lower social support than the active component of the armed forces [6, 7] and thus may be at increased risk for negative mental health outcomes [6, 8].

Social support is a multidimensional construct that can be assessed through both structural social support and perceived social support [9, 10]. Structural social support is often measured by the size of one’s social network (the number of members in the network) and by the diversity of one’s network (the different types of supportive roles filled by those network members) [9, 10]. Perceived social support is one’s subjective perception of the support received or available from one’s social network [9, 10]. Both types of support are associated with mental health outcomes [9, 10] and may be associated with mental health treatment participation [11–15].

Several lines of evidence suggest that larger social network size may be associated with better mental health in National Guard. Social network size is inversely associated with mental health problems in community samples [9, 10, 16–18], veterans [19–21], and other groups including cancer survivors [22]. One study found an inverse linear relationship between social network size and mental health conditions in veterans such that the probability of having a mental health condition was 38.3 % for those reporting no social network members, 28.1 % for those reporting one to two members, 18.5 % for those reporting three to five members, and 13.1 % for those reporting six or more members [20]. Social network size is also inversely associated with the severity of mental health problems [19], and social support may deteriorate as mental health conditions progress. For example, social network size decreased in Vietnam era veterans who developed PTSD as compared to veterans who did not [23]. However, the relationship between social network size and mental health has not been assessed in National Guard soldiers, who may have social networks in both civilian and military sectors, but also have prolonged periods of physical separation from both networks. There may also be unique links between community versus military social networks and mental health.

Perceived social support is another facet of social support that is likely related to mental health in National Guard. Low perceived social support has been associated with increased risk for depression [10, 24–31], posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [9, 32–35], psychological distress [36–38], and poor quality of life [22, 39] in multiple populations. This relationship may be particularly strong in military and veteran populations [21, 23, 34–36, 40–42]. In National Guard veterans, perceived post-deployment social support has been associated with fewer PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, and psychosocial difficulties [43–45]. However, it is unknown what the independent contributions of perceived and structural social support are on mental health in National Guard.

A specific component of perceived social support relevant to military populations is military unit support, defined as support from peers and leadership in one’s unit [46]. Low unit support is associated with higher incidence [43–45, 47, 48] and severity [49, 50] of depression and PTSD in active duty and veteran samples. Reservists report lower unit support than regular armed forces [6]; thus National Guard service members may be at particular risk for negative outcomes associated with low unit support. Prior findings of the relative effects on mental health functioning of perceived unit support versus perceived support from other sources have been mixed. In some studies, military social support has a larger impact than community (friend or family) support on mental health symptoms and service utilization in returning veterans [45, 51, 52]. However, one investigation of returning veterans found that community support was more protective against PTSD than unit support [53]. Given the dual social roles (military and civilian) inhabited by National Guard soldiers, the relationship between unit support and mental health problems would be better assessed in models that also included social network size and diversity, as well as perceived community support.

Some have argued that perceived social support is more closely associated with mental health than structural social support [54–57]. This argument is supported by studies that have found that perceived support mediates the effect of structural support on mental health problems or is a stronger predictor of mental health problems [16, 17, 21, 58–61] or of health care utilization [62, 63] than structural support. However, concerns have arisen that perceived social support might be influenced by negative mood states [64]. Thus, structural social support may potentially constitute a more “objective” way to measure social support because it is less influenced by concurrent mood. Furthermore, in at least one national survey, diversity of social support was more strongly associated with lower levels of PTSD symptoms than the perception of strong social support [9]. Thus, an assessment of social support that incorporates perceived support and structural components of the social network is critical to examining the relationship between support and health outcomes of interest to military populations.

Although the relationship between social support and mental health conditions tends to be relatively consistent, findings on the relationship between social support and mental health service utilization remain equivocal [52, 65–71]. Social networks and perceived social support may have both stress-reducing functions (reducing the psychological impact of stress) and positive referral functions (encouraging treatment when it is needed) [63]. Evidence for the referral function comes from the fact that social support has been associated with greater levels of mental health service utilization amongst individuals with PTSD [11–15]. This relationship extends to veteran samples [15, 52, 72]. A study by Harpaz-Rotem and colleagues [52] suggested that unit support might have particularly strong influence over mental health service initiation in veterans. The authors interpreted this finding to suggest that the unique relationships between soldiers during military service can have long-lasting effects on both subsequent mental health symptoms and on veterans’ attitudes about seeking mental health treatment when they do have symptoms [52]. In this case, social support may act as an enabling factor to facilitate treatment initiation [73].

In other studies with veteran samples, greater levels of social support are associated with reduced levels of mental health service utilization [74–77], suggesting a potential stress-reduction function. From this perspective, social support acts as a buffer to symptoms, thus reducing the need for care [78]. However, the source of support may alter the impact on service utilization. For instance, in a community sample of individuals who had experienced a stressful life event, greater perceived support from a spouse was associated with increased use of medical services, but greater support from friends and relatives was associated with decreased use of services [63]. Since different sources of social support may have different roles in facilitating or discouraging mental health service utilization, this remains an important topic of investigation in National Guard members.

Given the significant interrelationships between social support and mental health, the current study was designed to test the association between social support, social network characteristics, mental health symptoms, and mental health service utilization in National Guard service members with recent deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan. Though previous studies have addressed some of these topics in Vietnam era veterans, few have examined them in veterans from recent (OEF/OIF) conflicts, where the frequency of mental health problems is high [79, 80] but service utilization remains low [74, 81]. Since the experiences of service members from different combat eras may differ, as may levels of social support upon their return from deployments [23], this remains an important area of investigation. Furthermore, many previous studies have been limited by assessing only one facet of social support or social network characteristics [2], and no studies to date have concurrently assessed all four components of social support examined here (social network size, social network diversity, perceived unit support, and perceived general social support) or examined which aspects of social support are most closely connected to mental health in returning veterans. In addition, few previous investigations have controlled for mental health symptom severity in testing the relationship between social support and mental health service utilization, which is an important step since severity of mental illness is associated with both social support and with service utilization [15]. In the current study, we hypothesized that risk for mental health conditions would be independently associated with small social network size, low social network diversity, low perceived social support, and low perceived military unit support. We also hypothesized that greater rates of mental health service utilization would be associated with higher levels of perceived social and unit support and larger and more diverse social networks.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited from returning National Guard soldiers in a Midwestern state who completed surveys as part of a larger study to examine the health status of National Guard veterans and the implementation of a peer support program. Data collection extended from August 2011 to December 2013, with data being collected approximately 12 months following the soldiers’ return from overseas deployments to Iraq or Afghanistan. Soldiers were recruited in person via group announcements during monthly drill weekends and by mail using a slightly modified version of the Dillman method [82]. A total of 1448 National Guard members returned the survey, constituting 53 % of eligible National Guard members. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Data were collected under an approved waiver of written informed consent. For further details of the study, please see [83, 84].

Outcome variables

Probable mental health conditions

Probable mental health conditions were assessed via validated measures for PTSD, depression, generalized anxiety, and suicide risk. Suicide risk was included in this metric because a moderate-to-high level of suicidal behavior is often indicative of a mental health condition. Participants were coded as having a probable mental health condition if they had a positive screen on any one or more of the measures. PTSD symptoms were measured using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Specific Version (PCL-S), a self-report measure of the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms [85]. Probable PTSD was determined by a PCL-S score of ≥50. Depression was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 assesses nine DSM-IV symptoms of depression over a 2-week period and has a sensitivity of 88 % and a specificity of 88 % for major depression [86]. Probable depressive disorder was determined by a PHQ-9 score of ≥10 [87–90]. Generalized anxiety was assessed using the GAD-7 [91], a brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder with a sensitivity of 89 % and a specificity of 82 % [91]. Probable GAD was determined by a GAD-7 score of ≥10. Suicidal ideation was assessed using the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R), a 4-item measure that assesses different dimensions of suicidal thoughts and behaviors [92]. Suicide risk was determined by an SBQ-R score of ≥7. A composite measure was then generated in which participants were coded as either having at least one probable mental health condition or not having any probable mental health conditions. A positive score on any of the screening instruments was used to create a dichotomous (yes/no) variable reflecting any probable mental health condition.

Mental health service utilization

Mental health service utilization in the past year was assessed from 14 items that asked participants to indicate if they “had received mental health services for a stress, emotional, alcohol, or family problem” from either general medical or mental health providers in several different settings, including military, civilian, Veterans Affairs health clinics, or Vet Centers (see [83]). An affirmative response to receiving treatment from any of these providers in the past year was used to create a dichotomous variable reflecting any mental health treatment.

Independent variables

Social network size

A measure of social network size was created from the number of people (0–10) in a participant’s self-generated list of “of all the people you would go to if you needed support or help during a stressful time in your life.” Social network size was then dichotomized based on a median split [following 9, 10, 63].

Social network diversity

A measure of social network diversity was created from the number of relationship types (0–7) that a participant indicated receiving support from. For each individual in the participant’s self-generated list of social network members, the participant was asked to indicate his or her relationship with that person. Options included spouse or partner, family member, friend, coworker, professional help-giver, religious leader, or National Guard member. Participants were asked to check all options that applied. A participant was coded as receiving support from a particular type of relationship if they categorized at least one social network member as belonging to that relationship type. Social network diversity score was then dichotomized at the median.

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was assessed via the interpersonal support evaluation list-12 (ISEL-12), 12 items assessing perceived interpersonal support [93–95]. Items included statements such as, “If I were sick, I could easily find someone to help me with my daily chores”, and “If I wanted to go on a trip for a day, (for example, to the country or mountains), I would have a hard time finding someone to go with me.” Responses to each item were rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0, definitely false, to 3, definitely true. Negative items were reverse coded. Higher scores indicate higher levels of social support. The ISEL-12 has good convergent and divergent validity and adequate test–retest and internal reliability [35, 95, 96]. In the present sample, the ISEL-12 evidenced good internal consistency (α = .89)

Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory Unit Support Scale

The Unit Support Scale [46, 97] is a 10-item self-report instrument from the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) that assesses the amount of assistance and encouragement that an individual perceives from the military in general, unit leaders, and other unit members. Items include statements such as, “My unit was like family to me” and, “The commanding officer(s) in my unit were supportive of my efforts.” Responses to each item were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. The Unit Support Scale has good internal consistency and content validity [46]. In the present sample, the Unit Support Scale evidenced excellent internal consistency (α = .94).

Covariates

Age group (18–21, 22–30, 31–40, 41–50, and >50), sex (male/female), race/ethnicity (White/Nonwhite), income (<$25,000, $25,000–50,000, >$50,000), educational attainment (High School/GED, Some College/Associate’s Degree, Bachelor’s Degree or higher), rank (Enlisted, Noncommissioned Officer, Officer), and marital status (In/Not in Committed Relationship) were determined by soldiers’ responses to demographic items on the survey.

Hazardous alcohol use

Hazardous alcohol use was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C), a 3-item alcohol screen for hazardous drinking and active alcohol use disorders [98]. In men, a score of 4 or more is considered positive, and in women, a score of 3 or more is considered positive.

Combat exposure

Combat exposure was assessed via three questions from the Post-deployment Health Assessment, in regards to the most recent or any prior deployment: “Did you encounter dead bodies or see people killed or wounded?” (endorsed by 51 %), “Were you engaged in direct combat where you discharged a weapon?” (endorsed by 19 %), and “Did you ever feel that you were in great danger of being killed?” (endorsed by 57 %). 27 % reported exposure to one item, 25 % to two items, and 17 % to all three items. An affirmative response to at least one of the three questions was used to create a dichotomous measure of combat exposure status for each participant [99].

Physical health

Physical health was assessed via the Short Form-12 Health Survey Physical component score, which provides a brief, overall summary of physical health functioning for the past four weeks [100]. Items assess the participant’s subjective opinion of his/her health (e.g., “excellent” to “poor”) and the extent to which physical health limits the participant’s day-to-day activities. The physical health component has a score range of 0–100, with higher scores indicating better health.

Data analysis

All of the analyses for this study were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., 2010). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize social network and social support levels in the sample. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests examined the relationships between social network measures and probable mental health conditions and between social network measures and mental health services utilization. Multivariable logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the dependent variables of mental health condition and mental health service utilization.

Due to prior work demonstrating a strong association between mental health service utilization and mental health need [15, 101], mental health need was added as a covariate in models predicting utilization. For these models, the number of probable mental health conditions was categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The final sample consisted of 1448 soldiers, including 441 (30.6 %) who had screening scores consistent with meeting diagnostic criteria for at least one mental health condition. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The average number of people listed in the social network was almost 4 (mean ± SD = 3.9 ± 3.1). Family members, other than a spouse, were the most commonly reported relationship in a participant’s social network, listed by 59 % of the sample. 55 % of the sample listed a spouse, 55 % listed a friend, and 26 % listed a National Guard unit member in their social network. Correlations between dichotomous measures of social support were small to medium in size (see Table 2).

Bivariate analyses

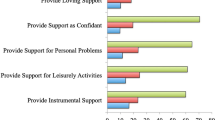

Participants with probable mental health conditions listed fewer individuals (M ± SD = 3.1 ± 2.9 vs. 4.2 ± 3.1, p < .001) and fewer types of relationships (1.9 ± 1.5 vs. 2.3 ± 1.4, p < .001) in their social network, and reported lower perceived social support (ISEL score of 22.2 ± 7.6 vs. 28.5 ± 6.4, p < .001) and lower unit support (DRRI US score of 30.1 ± 10.1 vs. 35.9 ± 8.6, p < .001; see Table 3). There were no differences in the number of people or types of relationships by receipt of mental health treatment, but those who received mental health treatment reported lower perceived support (M ± SD = 24.7 ± 7.5 vs. 27.4 ± 7.1, p < .001) and lower unit support (32.0 ± 9.8 vs. 35.0 ± 9.3, p < .001).

Logistic regression analyses

Table 4 presents results from the adjusted logistic regression model estimating the association between social network measures and probable mental health condition as the outcome. Greater perceived social support (OR .90, CI .88–.92) and greater unit support (OR .96, CI .94–.97) were significantly associated with lower likelihood of having a probable mental health condition. Social network size and diversity were not significantly associated with likelihood of having a mental health condition. For every 1 point increase in perceived social support score, there was a 10 % decrease in the odds of having a mental health condition. For every 1 point increase in unit support score, there was a 4 % decrease in the odds of having a mental health condition.

Since perceived social support may be correlated with mood, we conducted a supplementary analysis in which only structural elements of social support (social network size and social network diversity) were included as predictors of mental health conditions. In this model, larger social network size (OR .58, CI .42–.78) but not social network diversity was significantly associated with lower likelihood of having a probable mental health condition.

Table 5 presents results from the logistic regression model estimating the association between social network measures and mental health service utilization as the outcome.

In models that were unadjusted for mental health symptoms, perceived social support and unit support were significantly associated with reduced likelihood of service utilization (data not shown). However, after adjusting for probable mental health conditions, these associations were no longer significant. Significant predictors of service utilization included mental health conditions, combat exposure, and poor physical health (see Table 5). The likelihood of mental health service utilization increased with greater numbers of mental health conditions. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the impact on services use of the interaction between measures of social support and mental health symptoms. These interaction terms were not significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation into the relationship between multiple measures of social networks and perceived social support, mental health, and mental health service utilization in returning National Guard veterans. Using data from 1,448 recently returned OEF/OIF National Guard veterans, we found that network size and perceived support were lower than has been reported for other veteran populations [19, 23, 35]. We also found that social support was closely connected to mental health. In particular, all four social network or support measures were associated with mental health conditions in bivariate analyses, and perceived social support and military unit support remained significant in adjusted analyses. Social support appeared less relevant to mental health service utilization than to mental health symptoms.

Our findings linking social networks to mental health are largely consistent with previous studies showing that social networks [16–22], perceived social support [21–42], and unit support [43–50] are all related to mental health symptoms. We replicated previous findings in National Guard that perceived support and unit support are important predictors of mental health [43–45], and also demonstrated that social network size may be another important predictor. We did not find a significant association between social network diversity and mental health problems. This lack of association may be due in part to a restriction of range in the types of relationships assessed (0–6 types of social network members). It may also be due in part to the moderate correlation between network size and network diversity. Nonetheless, on the whole, our findings indicate that several aspects of National Guard service members’ social networks are significantly related to mental health, including their overall amount of perceived support and the amount of support perceived from unit members.

Our results also suggest that social network and perceived social support scores may be comparatively low in National Guard. The social network size in our sample was lower than in other veteran [19, 23] and civilian [9] samples. Similarly, social support scores as measured via the ISEL were lower than those of other veteran populations [35] and the general population [9]. It is possible that recent returns from deployment may have a detrimental impact on one’s social network. Social network theorists hypothesize that life transitions alter social networks in several ways. They may be altered because one identifies oneself in new ways, compares oneself to new reference groups, or perceives weakened ties with previous social networks due to decreased perceptions of similarity with those networks [102]. Decreases in social support upon return from deployment may also be due to difficulty adjusting back to civilian life, a sense of being unable to share experiences with others, or a negative community response to war or to service members [23]. However, the change in social support upon return from deployment may vary by combat era [23], highlighting the importance of studying this association in OEF/OIF era veterans. Veterans returning to their communities rather than military bases may be at particular risk for the negative effects of low social support, since, as compared to active duty members, separated veterans report smaller social networks and participation in fewer social activities outside work [20]. Further research is needed to determine the causes of reduced social network size in returning National Guard veterans and the implications of this finding on longer-term health outcomes.

Though social network measures were linked to mental health symptoms, we did not find an association between these measures and mental health service utilization. Previous research indicates that social support may have a bidirectional effect on treatment seeking. For instance, in a qualitative study of returning veterans, Sayer and colleagues [70] found that social network facilitation and encouragement were associated with increased likelihood of engaging in treatment, but that other social network functions (societal rejection, negative homecoming experiences, withdrawal from social networks, or social network discouragement of health-seeking) were considered barriers to treatment [70]. Thus, one’s social network may have a facilitating or an impeding role on mental health service utilization, depending on the messages provided by network members. Another study found that having either no social network or having a large network was associated with greater mental health service utilization [103]. Consequently, the relationship between social network size and likelihood of treatment utilization may not be linear. It is also possible that individuals on opposite ends of the social network continuum may access care for different reasons. In our sample, need factors including mental health and physical health problems appeared to be more important determinants of mental health service utilization than social network measures. Given that social network measures were significantly related to mental health service utilization in unadjusted models but were no longer significant in adjusted models, it is possible that this association may be driven at least in part by increased levels of mental health problems. However, since these are cross-sectional and not longitudinal data, casual implications cannot be determined. Future work should further examine the facilitatory and inhibitory properties of social networks of different sizes and compositions.

The current findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, we used self-report questionnaires to indicate probable mental health conditions. Though these measures are highly correlated with clinician-administered diagnostic interviews [104], they may be subject to response bias. Secondly, our findings are cross-sectional; thus no conclusions can be drawn about causality. Low social support may increase the risk for mental health symptoms [105, 106], or mental health symptoms may cause deterioration of social support [107]. Furthermore, any causal relationships between mental health and social support levels may vary over the course of a person’s mental illness and the influence of social networks on treatment utilization may require a longer timeframe than the yearlong period examined in this study [107]. Third, in our model predicting service utilization, we did not restrict our sample to just those individuals who had probable mental health conditions at the time of the 12-month survey. We decided to include currently non-symptomatic individuals in the sample because they represented 42 % of the veterans who had received mental health services in the past year. Fourth, our sample was 92 % men, so further investigation is needed to determine whether these findings apply to women. Finally, only 53 % of the eligible samples returned the survey, thus it is possible that unmeasured selection pressures introduced bias.

In conclusion, the current study tested the association between mental health symptoms, service utilization, and several social network and social support measures, including social network size, social network diversity, perceived social support, and military unit support. We found that both general and military-specific perceived social support were associated with the presence of probable mental health conditions. Given this association, military leaders and treatment providers might wish to continue efforts to bolster social supports in National Guard’s communities and in their military units. Clinicians might facilitate the development of augmented social networks for their patients through group, couples, or family therapy or through other social or informational groups [2]. Treatment might also focus on enhancing social functioning, including promoting interactions with a greater number of individuals outside the preexisting social network or improving relationships with individuals already in the network. In addition, future work could investigate ways to boost National Guard cohesion in between drill weekends or ways to leverage social support to normalize and encourage mental health treatment when it is needed. Other strategies, such as targeted outreach programs, might also be needed to increase mental health treatment use among National Guard members with mental health need.

References

Wallston BS, Alagna SW, DeVellis BM, DeVellis RF (1983) Social support and physical health. Health Psychol 2(4):367–391

Flannery RB (1990) Social support and psychological trauma: a methodological review. J Trauma Stress 3(4):593–611

Uchino BN (2009) What a lifespan approach might tell us about why distinct measures of social support have differential links to physical health. J Soc Pers Relat 26(1):53–62. doi:10.1177/0265407509105521

Cohen S (2004) Social relationships and health. Am Psychol 59(8):676–684. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D (1988) Social relationships and health. Science 241(4865):540–545

Browne T, Hull L, Horn O, Jones M, Murphy D, Fear NT, Greenberg N, French C, Rona RJ, Wessely S, Hotopf M (2007) Explanations for the increase in mental health problems in UK reserve forces who have served in Iraq. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 190:484–489. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030544

Vogt DS, Samper RE, King DW, King LA, Martin JA (2008) Deployment stressors and posttraumatic stress symptomatology: comparing active duty and National Guard/Reserve personnel from Gulf War I. J Trauma Stress 21(1):66–74. doi:10.1002/jts.20306

Harvey SB, Hatch SL, Jones M, Hull L, Jones N, Greenberg N, Dandeker C, Fear NT, Wessely S (2011) Coming home: social functioning and the mental health of UK Reservists on return from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Ann Epidemiol 21(9):666–672. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.05.004

Platt J, Keyes KM, Koenen KC (2014) Size of the social network versus quality of social support: which is more protective against PTSD? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49(8):1279–1286. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0798-4

Smyth N, Siriwardhana C, Hotopf M, Hatch SL (2014) Social networks, social support and psychiatric symptoms: social determinants and associations within a multicultural community population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0943-8

Ullman SE, Brecklin LR (2002) Sexual assault history, PTSD, and mental health service seeking in a national sample of women. J Community Psychol 30(3):261–279. doi:10.1002/jcop.10008

Sautter FJ, Glynn SM, Thompson KE, Franklin L, Han X (2009) A couple-based approach to the reduction of PTSD avoidance symptoms: preliminary findings. J Marital Fam Ther 35(3):343–349. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00125.x

Sherbourne CD (1988) The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Soc Sci Med 27(12):1393–1400

Mitchell ME (1989) The relationship between social network variables and the utilization of mental health services. J Community Psychol 17(3):258–266. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(198907)17:3<258:aid-jcop2290170308>3.0.co;2-l

Meis LA, Barry RA, Kehle SM, Erbes CR, Polusny MA (2010) Relationship adjustment, PTSD symptoms, and treatment utilization among coupled National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. J Fam Psychol 24(5):560–567. doi:10.1037/a0020925

Lin N, Ye X, Ensel WM (1999) Social support and depressed mood: a structural analysis. J Health Soc Behav 40(4):344–359

Kawachi I, Berkman LF (2000) Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I (eds) Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 174–190

Chou KL, Liang K, Sareen J (2011) The association between social isolation and DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 72(11):1468–1476. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06019gry

Escobar JI, Randolph ET, Puente G, Spiwak F, Asamen JK, Hill M, Hough RL (1983) Post-traumatic stress disorder in Hispanic Vietnam veterans. Clinical phenomenology and sociocultural characteristics. J Nerv Mental Dis 171(10):585–596

Hatch SL, Harvey SB, Dandeker C, Burdett H, Greenberg N, Fear NT, Wessely S (2013) Life in and after the Armed Forces: social networks and mental health in the UK military. Sociol Health Illn 35(7):1045–1064. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12022

King LA, King DW, Fairbank JA, Keane TM, Adams GA (1998) Resilience-recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. J Pers Soc Psychol 74(2):420–434

Soares A, Biasoli I, Scheliga A, Baptista RL, Brabo EP, Morais JC, Werneck GL, Spector N (2013) Association of social network and social support with health-related quality of life and fatigue in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma. Support Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 21(8):2153–2159. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1775-x

Keane TM, Scott WO, Chavoya GA, Lamparski DM, Fairbank JA (1985) Social support in Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a comparative analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 53(1):95–102

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98(2):310–357

Barnett PA, Gotlib IH (1988) Psychosocial functioning and depression: distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychol Bull 104(1):97–126

Schuster TL, Kessler RC, Aseltine RH Jr (1990) Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. Am J Community Psychol 18(3):423–438

Turner RJ (1981) Social support as a contingency in psychological well-being. J Health Soc Behav 22(4):357–367. doi:10.2307/2136677

Fuller-Thomson E, Battiston M, Gadalla TM, Brennenstuhl S (2014) Bouncing back: remission from depression in a 12-year panel study of a representative Canadian community sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49(6):903–910. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0814-8

Salinero-Fort MA, Jimenez-Garcia R, de Burgos-Lunar C, Chico-Moraleja RM, Gomez-Campelo P (2014) Common mental disorders in primary health care: differences between Latin American-born and Spanish-born residents in Madrid. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, Spain. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0962-5

Handley TE, Inder KJ, Kelly BJ, Attia JR, Lewin TJ, Fitzgerald MN, Kay-Lambkin FJ (2012) You’ve got to have friends: the predictive value of social integration and support in suicidal ideation among rural communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(8):1281–1290. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0436-y

Sundermann O, Onwumere J, Kane F, Morgan C, Kuipers E (2014) Social networks and support in first-episode psychosis: exploring the role of loneliness and anxiety. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49(3):359–366. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0754-3

Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE (2002) Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 11(5):465–476. doi:10.1089/15246090260137644

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(5):748–766

Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS (2003) Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 129(1):52–73

Dinenberg RE, McCaslin SE, Bates MN, Cohen BE (2014) Social support may protect against development of posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Health Promot 28(5):294–297. doi:10.4278/ajhp.121023-QUAN-511

Kadushin C (1983) Mental health and the interpersonal environment: a reexamination of some effects of social structure on mental health. Am Sociol Rev 48(2):188–198

Marchand A, Durand P, Haines V 3rd, Harvey S (2014) The multilevel determinants of workers’ mental health: results from the SALVEO study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0932-y

Myklestad I, Roysamb E, Tambs K (2012) Risk and protective factors for psychological distress among adolescents: a family study in the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(5):771–782. doi:10.1007/s00127-011-0380-x

Modie-Moroka T (2014) Stress, social relationships and health outcomes in low-income Francistown, Botswana. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49(8):1269–1277. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0806-8

Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD (2000) Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(5):748–766

Boscarino JA (1995) Post-traumatic stress and associated disorders among Vietnam veterans: the significance of combat exposure and social support. J Trauma Stress 8(2):317–336

Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM (2012) The role of coping, resilience, and social support in mediating the relation between PTSD and social functioning in veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychiatry 75(2):135–149. doi:10.1521/psyc.2012.75.2.135

Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Southwick SM (2010) Structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and psychosocial functioning in Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Psychiatry Res 178(2):323–329. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.039

Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Morgan CA, Southwick SM (2010) Psychosocial buffers of traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, and psychosocial difficulties in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom: the role of resilience, unit support, and postdeployment social support. J Affect Disord 120(1–3):188–192. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015

Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM (2009) Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depress Anxiety 26(8):745–751. doi:10.1002/da.20558

King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, Samper RE (2006) Deployment risk and resilience inventory: a collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Mil Psychol 18(2):89–120. doi:10.1207/S15327876mp1802_1

Vogt DS, Pless AP, King LA, King DW (2005) Deployment stressors, gender, and mental health outcomes among Gulf War I veterans. J Trauma Stress 18(3):272–284. doi:10.1002/jts.20044

Iversen AC, Fear NT, Ehlers A, Hacker Hughes J, Hull L, Earnshaw M, Greenberg N, Rona R, Wessely S, Hotopf M (2008) Risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder among UK Armed Forces personnel. Psychol Med 38(4):511–522. doi:10.1017/S0033291708002778

Brailey K, Vasterling JJ, Proctor SP, Constans JI, Friedman MJ (2007) PTSD symptoms, life events, and unit cohesion in US soldiers: baseline findings from the neurocognition deployment health study. J Trauma Stress 20(4):495–503. doi:10.1002/jts.20234

Dickstein BD, McLean CP, Mintz J, Conoscenti LM, Steenkamp MM, Benson TA, Isler WC, Peterson AL, Litz BT (2010) Unit cohesion and PTSD symptom severity in Air Force medical personnel. Mil Med 175(7):482–486

Smith BN, Vaughn RA, Vogt D, King DW, King LA, Shipherd JC (2013) Main and interactive effects of social support in predicting mental health symptoms in men and women following military stressor exposure. Anxiety Stress Coping 26(1):52–69. doi:10.1080/10615806.2011.634001

Harpaz-Rotem I, Rosenheck RA, Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM (2014) Determinants of prospective engagement in mental health treatment among symptomatic Iraq/Afghanistan veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis 202(2):97–104. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000078

Han SC, Castro F, Lee LO, Charney ME, Marx BP, Brailey K, Proctor SP, Vasterling JJ (2014) Military unit support, postdeployment social support, and PTSD symptoms among active duty and National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. J Anxiety Disord 28(5):446–453. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.04.004

Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D, Southwick S (2007) Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry 4(5):35–40

Fleming R, Baum A, Gisriel MM, Gatchel RJ (1982) Mediating influences of social support on stress at Three Mile Island. J Hum Stress 8(3):14–22. doi:10.1080/0097840X.1982.9936110

Ozer EJ, Weinstein RS (2004) Urban adolescents’ exposure to community violence: the role of support, school safety, and social constraints in a school-based sample of boys and girls. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 33(3):463–476. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_4

Eriksson CB, Vande Kemp H, Gorsuch R, Hoke S, Foy DW (2001) Trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms in international relief and development personnel. J Trauma Stress 14(1):205–212. doi:10.1023/A:1007804119319

Teo AR, Choi H, Valenstein M (2013) Social relationships and depression: ten-year follow-up from a nationally representative study. PLoS ONE 8(4):e62396. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062396

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA (2010) Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging 25(2):453–463. doi:10.1037/a0017216

Golden J, Conroy RM, Bruce I, Denihan A, Greene E, Kirby M, Lawlor BA (2009) Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24(7):694–700. doi:10.1002/gps.2181

Tempier R, Balbuena L, Lepnurm M, Craig TK (2013) Perceived emotional support in remission: results from an 18-month follow-up of patients with early episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(12):1897–1904. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0701-3

Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, deGruy FV, Kaplan BH (1989) Functional versus structural social support and health care utilization in a family medicine outpatient practice. Med Care 27(3):221–233

Maulik PK, Eaton WW, Bradshaw CP (2011) The effect of social networks and social support on mental health services use, following a life event, among the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area cohort. J Behav Health Serv Res 38(1):29–50. doi:10.1007/s11414-009-9205-z

Munoz-Laboy M, Severson N, Perry A, Guilamo-Ramos V (2014) Differential impact of types of social support in the mental health of formerly incarcerated latino men. Am J Mens Health 8(3):226–239. doi:10.1177/1557988313508303

Price M, Davidson TM, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Resnick HS (2014) Predictors of using mental health services after sexual assault. J Trauma Stress 27(3):331–337. doi:10.1002/jts.21915

Spoont MR, Nelson DB, Murdoch M, Rector T, Sayer NA, Nugent S, Westermeyer J (2014) Impact of treatment beliefs and social network encouragement on initiation of care by VA service users with PTSD. Psychiatr Serv 65(5):654–662. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200324

Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM (2009) Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatr Serv 60(8):1118–1122. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.8.1118

Albert M, Becker T, McCrone P, Thornicroft G (1998) Social networks and mental health service utilisation—a literature review. Int J Soc Psychiatry 44(4):248–266

Fikretoglu D, Brunet A, Guay S, Pedlar D (2007) Mental health treatment seeking by military members with posttraumatic stress disorder: findings on rates, characteristics, and predictors from a nationally representative Canadian military sample. Can J Psychiatry 52(2):103–110

Sayer NA, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Spoont M, Murdoch M, Parker LE, Chiros C, Rosenheck R (2009) A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry 72(3):238–255. doi:10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.238

Sripada RK, Pfeiffer PN, Rauch SA, Bohnert KM (2015) Social support and mental health treatment among persons with PTSD: results of a nationally representative survey. Psychiatr Serv 66(1):65–71. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400029

Smith-Osborne A (2009) Mental health risk and social ecological variables associated with educational attainment for gulf war veterans: implications for veterans returning to civilian life. Am J Community Psychol 44(3–4):327–337. doi:10.1007/s10464-009-9278-0

Andersen RM (1995) Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 36(1):1–10

Interian A, Kline A, Callahan L, Losonczy M (2012) Readjustment stressors and early mental health treatment seeking by returning National Guard soldiers with PTSD. Psychiatr Serv 63(9):855–861. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100337

Kehle SM, Polusny MA, Murdoch M, Erbes CR, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, Meis LA (2010) Early mental health treatment-seeking among U.S. National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. J Trauma Stress 23(1):33–40. doi:10.1002/jts.20480

Sayer NA, Clothier B, Spoont M, Nelson DB (2007) Use of mental health treatment among veterans filing claims for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 20(1):15–25. doi:10.1002/jts.20182

Lehavot K, Der-Martirosian C, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Washington DL (2013) The role of military social support in understanding the relationship between PTSD, physical health, and healthcare utilization in women veterans. J Trauma Stress 26(6):772–775. doi:10.1002/jts.21859

Gourash N (1978) Help-seeking: a review of the literature. Am J Community Psychol 6(5):413–423

Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW (2007) Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA 298(18):2141–2148. doi:10.1001/jama.298.18.2141 298/18/2141 [pii]

Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW (2010) Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(6):614–623. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54

Kehle SM, Polusny MA, Murdoch M, Erbes CR, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, Meis LA (2010) Early mental health treatment-seeking among US National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. J Trauma Stress 23(1):33–40. doi:10.1002/jts.20480

Dillman D, Smyth J, Christian L (2009) Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Wiley, New York

Valenstein M, Gorman L, Blow AJ, Ganoczy D, Walters H, Kees M, Pfeiffer PN, Kim HM, Lagrou R, Wadsworth SM, Rauch SA, Dalack GW (2014) Reported barriers to mental health care in three samples of U.S. Army National Guard soldiers at three time points. J Trauma Stress 27(4):406–414. doi:10.1002/jts.21942

Bonar EE, Bohnert KM, Walters HM, Ganoczy D, Valenstein M (2014) Student and nonstudent national guard service members/veterans and their use of services for mental health symptoms. J Am Coll Health: 0. doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.975718

Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM (1991) PCL for DSM-IV. In. National Center for PTSD—Behavioral Science Division, Boston

Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K (2004) Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care 42(12):1194–1201

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B (2010) The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 32(4):345–359. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2001) The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB (1999) Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. J Am Med Assoc 282(18):1737–1744. doi:10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

Wittkampf KA, Naeije L, Schene AH, Huyser J, van Weert HC (2007) Diagnostic accuracy of the mood module of the patient health questionnaire: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 29(5):388–395. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.004

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX (2001) The suicidal behaviors questionnaire-revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment 8(4):443–454

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98(2):310–357

Cohen S, Hoberman HM (1983) Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. J Appl Soc Psychol 13(2):99–125. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb02325.x

Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Karmarck TW, Hoberman H (1985) Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR (eds) Social support: theory, research and application. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague

Merz EL, Roesch SC, Malcarne VL, Penedo FJ, Llabre MM, Weitzman OB, Navas-Nacher EL, Perreira KM, Gonzalez F, Ponguta LA, Johnson TP, Gallo LC (2014) Validation of Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12) Scores Among English- and Spanish-Speaking Hispanics/Latinos From the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychol Assess 26(2):384–394. doi:10.1037/a0035248

Vogt DS, Proctor SP, King DW, King LA, Vasterling JJ (2008) Validation of scales from the deployment risk and resilience inventory in a sample of operation Iraqi freedom veterans. Assessment 15(4):391–403. doi:10.1177/1073191108316030

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA (1998) The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Arch Intern Med 158(16):1789–1795

Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS (2006) Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295(9):1023–1032. doi:10.1001/jama.295.9.1023

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–233

Fasoli DR, Glickman ME, Eisen SV (2010) Predisposing characteristics, enabling resources and need as predictors of utilization and clinical outcomes for veterans receiving mental health services. Med Care 48(4):288–295

Suitor J, Keeton S (1997) Once a friend, always a friend? Effects of homophily on women’s support networks across a decade. Soc Netw 19(1):51–62. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(96)00290-0

Auslander GK, Soskolne V, Ben-Shahar I (2005) Utilization of health social work services by older immigrants and veterans in Israel. Health Soc Work 30(3):241–251

Monson CM, Gradus JL, Young-Xu Y, Schnurr PP, Price JL, Schumm JA (2008) Change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: do clinicians and patients agree? Psychol Assess 20(2):131–138. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.131

Karstoft KI, Armour C, Elklit A, Solomon Z (2013) Long-term trajectories of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans: the role of social resources. J Clin Psychiatry 74(12):e1163–e1168. doi:10.4088/JCP.13m08428

Lowe SR, Galea S, Uddin M, Koenen KC (2014) Trajectories of posttraumatic stress among urban residents. Am J Community Psychol 53(1–2):159–172. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9634-6

Kaniasty K, Norris FH (2008) Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: sequential roles of social causation and social selection. J Trauma Stress 21(3):274–281. doi:10.1002/jts.20334

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service, RRP 09-420 and SDP 10-047; the Welcome Back Veterans Initiative, the McCormick Foundation, and Families and Communities Together Coalition of Michigan State University. Writing of this manuscript was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Veterans Affairs Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center (SMITREC) and the Mental Health Service of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System and was therefore performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Data were collected under an approved waiver of written informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sripada, R.K., Bohnert, A.S.B., Teo, A.R. et al. Social networks, mental health problems, and mental health service utilization in OEF/OIF National Guard veterans. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 1367–1378 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1078-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1078-2