Abstract

Background

Self-inflicted injuries represent a consistent cause of trauma and falls from heights (FFH) represent a common dynamic used for suicidal attempts. The aim of the current report is to compare, among FFH patients, unintentional fallers and intentional jumpers in terms of demographical characteristics, clinical-pathological parameters and mortality, describing the population at risk for suicide by jumping and the particular patterns of injury of FFH patients.

Materials and methods

The present study is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data regarding FFH patients, extracted from the Trauma Registry of the Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, Italy. Demographic characteristics, clinical-pathological parameters, patterns of injury, outcomes including mortality rates of jumpers and fallers were analyzed and compared.

Results

The FFH trauma group included 299 patients between April 2014 and July 2016: 259 of them (86.6%) were fallers and 40 (13.4%) were jumpers. At multivariate analysis both young age (p = 0.01) and female sex (p < 0.001) were statistical significant risk factors for suicidal attempt with FFH. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) at the arrival was lower and ISS was higher in the self-inflicted injury group (SBP 133.35 ± 23.46 in fallers vs 109.89 ± 29.93 in jumpers, p < 0.001; ISS in fallers 12.61 ± 10.65 vs 18.88 ± 11.80 in jumpers, p = 0.001). Jumpers reported higher AIS score than fallers for injuries to: face (p = 0.023), abdomen (p < 0.001) and extremities (p = 0.004). The global percentage of patients who required advanced or definitive airway control was significantly higher in the jumper group (35.0% vs 16.2%, p = 0.005). In total, 75% of jumpers and the 34% of fallers received surgical intervention (p < 0.001). A higher number of jumpers needed ICU admission, as compared to fallers (57.5% vs 23.6%, p < 0.001); jumpers showed longer total length of stay (26.00 ± 24.34 vs 14.89 ± 13.04, p = 0.007) and higher early mortality than fallers (7.5% vs 1.2%, p = 0.008).

Conclusions

In Northern Italy, the population at highest risk of suicide by jumping and requiring Trauma Team activation is greatly composed by middle-aged women. Furthermore, FFH is the most common suicidal method. Jumpers show tendency to “feet-first landing” and seem to have more severe injuries, worse outcome and a higher early mortality rate, as compared to fallers. The Trauma Registry can be a useful tool to describe clusters of patients at high risk for suicidal attempts and to plan preventive and clinical actions, with the aim of optimizing hospital care for FFH trauma patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Self-inflicted injuries represent a consistent cause of trauma and falls from heights (FFH) represent a common dynamic used for suicidal attempts. The World Health Organization (WHO) records that 800,000 people commit suicide each year, representing an annual global age-standardized suicide rate of 11.4 per 100,000 inhabitants [1,2,3]. In the United Kingdom, jumping from a height accounts for 3–15% of the 140,000 suicidal attempts annually and this incidence seems similar to the rest of Europe [3,4,5].

Both accidental (fallers) and intentional (jumpers) FFH trauma patients often sustain multiple injuries and require complex therapeutic management. In the last years, research has focused on the identification of patterns of injuries and on their correlation with the mechanisms of lesions, to provide an optimal risk stratification for a tailored treatment. Understanding whether a consistent difference exists between accidental and intentional FFH with regards to patterns of injuries and outcomes could help to achieve higher quality of care for these patients. In this context, recognizing the population at risk of suicide may help to create tailored prevention programs.

The aim of the current work is to compare fallers and jumpers in terms of patient characteristics, patterns of injury and outcomes—including mortality. The secondary end-point is to identify the population at risk of suicidal attempt by jumping.

Materials and methods

Data were extracted from the Trauma Registry of the Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital in Bergamo, focusing on accidental and voluntary FFH with at least 1-year follow-up. The database includes only adult patients (from the age of 18 years), while patients who died prior to the ED admission were excluded.

Demographic data, information on trauma dynamics, mechanism of lesions (intentional or accidental), pattern of injuries, treatment and outcomes were collected. FFH patients were classified into two distinct groups: accidental falls (referred to as “fallers”) and intentional falls (referred to as “jumpers”). All other types of self-inflicted lesions were excluded.

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS (version 20 for Windows; SPSS, Inc.).

Results

The Trauma Registry from April 2014 to July 2016 included 1576 patients. In this population, 42 (2.7%) were intentional trauma cases (suicide attempts) and 1534 (97.3%) were accidental (Table 1). In the group including suicidal cases, 40 (95.2%) were FFH and 2 (4.8%) were other dynamics (train collision). In the accidental trauma group, 259 (16.9%) were FFH. Thus, the FFH trauma groups included 299 patients: 259 (86.6%) fallers and 40 (13.4%) jumpers. Jumping represents the most commonly used mechanism for the suicidal attempt, compared to other methods of self-inflicted trauma in the study population (p < 0.001). Table 2 summarizes FFH patients’ characteristics.

Jumpers were significantly younger than fallers (fallers: 56.14 ± 17.12 vs jumpers: 44.85 ± 15.94, p < 0.001). Among jumpers there was a higher percentage of female patients than in fallers group (62.5% in jumpers vs 16.2% in fallers, p < 0.001).

At multivariate analysis, both younger age (p = 0.01) and female sex (p < 0.001) were identified as risk factors for suicide by jump.

Accidental FFH were predominantly connected to alpine leisure activities (23.9%) and occupational activities (12.0%), while the majority of intentional FFH (32.5%) occurred in a domestic environment (p < 0.001).

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) at the arrival in the ED was higher in the fallers group (SBP 133.35 ± 23.46 in fallers group and 109.89 ± 29.93 in jumpers group, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the percentage of patients presenting with traumatic shock (SBP < 90 mmHg) was significantly higher within the jumpers group (24.3% in jumpers vs 3.7% in fallers, p < 0.001).

There was no significant difference in GCS and AIS of head injuries between fallers and jumpers (GCS: fallers 13.63 ± 3.38, jumpers 12.05 ± 4.98, p = n.s.; AIS head > 2: fallers 44.4%, jumpers 55.0%, p = n.s.).

The ISS in the jumpers group was higher than in the fallers group (ISS: fallers 12.61 ± 10.65, jumpers 18.88 ± 11.80, p = 0.001).

The global percentage of patients who needed a definitive airway control (EET) and the percentage of patients who needed a definitive airway at the trauma scene was higher in jumpers group (global: 35.0% vs 16.2%, p = 0.005; on the scene: 27.5% vs 11.2%, p = 0.005).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of injuries. Jumpers reported higher AIS score than fallers for facial lesions (p = 0.023), abdominal lesions (p < 0.001) and injuries to the extremities (p = 0.004).

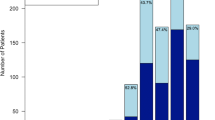

A total of 213 patients (71.2%) in the FFH population were hospitalized; 69.5% of fallers and the 82.5% of jumpers were admitted (p = n.s.). Figure 2 shows the Departments of destination of the hospitalized patients after the evaluation in ED. Trauma-surgery department resulted to be the main receiver of patients who did not need intensive care. A higher number of jumpers than fallers needed ICU admission (57.5% vs 23.6%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, 75% of jumpers and 34% of fallers received surgical intervention (p < 0.001).

Jumpers did not show a significantly longer ICU stay as compared to fallers (12.17 ± 18.84 vs 12.32 ± 14.42, p = n.s.); however, they had a longer total hospital stay (26.00 ± 24.34 vs 14.89 ± 13.04, p = 0.007).

Overall, hospital mortality after FFH was 6.7%. There was a significantly higher mortality in ED for jumpers than for fallers (jumpers 7.5% vs fallers 1.2%, p = 0.008), but there was no difference between the two groups of patients in terms of mortality during hospital stay (fallers 4.2% vs jumpers 7.5%, p = n.s.) and of 1-year mortality (fallers 10.0% vs jumpers 17.9%, p = n.s.). Only one patient who sustained an intentional FFH died after 7 months from discharge, while ten faller patients died after discharge from hospital and among them nine were over 80 years old.

Discussion

The present study confirms the Italian national epidemiologic data (ISTAT) [6], which report that the population at highest risk of suicide by jumping in Italy is composed by middle-aged women and the most common setting is the domestic one. These data are in contrast with data from United Kingdom, according to which the typical patient who attempts suicide by jumping is the middle aged, unemployed and single male, often with an associated psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, personality disorders, depression, mood disorders, organic illness, and substances abuse [3, 4, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Unfortunately, due to missing data, the present paper could not consider a past medical history of psychiatric disorders or if there were previous episodes of attempted suicides.

As a result of the present study, in our setting, tailored preventive actions should be directed to middle-aged women, and particular attention should be paid to the domestic environment.

According to the present data, FFH is the most common method for suicidal attempt in a Northern Italian area, and this is in contradiction with national epidemiologic data, which reports it as the second most common mechanism [6]. On the other hand, according to present data and to the American College of Surgeon results [16], the population at highest risk for accidental FFH is composed by mountain sports performers (especially winter sports, such as skiing and ski climbing/hiking) and work activities. Therefore, preventive actions should be applied also for these groups of fallers.

The FFH patterns of injury are debated in current literature and only few studies [17, 18] reported a comparison between jumpers and fallers. The current study, as previously found by the other authors [17,18,19], confirms the tendency to the “feet-first landing” in jumpers, as these patients have significantly higher AIS score for the extremities than fallers. Conversely, accidental fallers tend to fall in a variety of random positions [17]. Nevertheless, this study did not confirm the fact that “feet-first landing” is a protective factor for head trauma [9, 17], because there was no significant difference between frequency and gravity of head trauma between jumpers and fallers. It is likely that fallers and jumpers with severe head trauma (i.e., the ‘head-first-landing’ patients) have a higher mortality rate on the scene [18]; these groups of patients are probably missed and not recorded in the Trauma Registry.

In contrast with results by the other authors [8, 18, 20], there was a higher AIS score for the abdomen among jumpers, probably due to the deceleration damage. The current study did not report a statistically significant difference in the severity of chest trauma between fallers and jumpers, but this is likely to be a further effect of a selection bias, as severe chest trauma [11] is likely to be associated with high mortality on the scene.

With regards to the severity of injuries related to intentional or accidental FFH [11, 18, 21,22,23,24], Richter et al. reported no significant differences in severity of traumatic injuries caused by either accidental falling or deliberate jumping [18], while Dickinson et al. showed that jumpers have higher ISS and mortality than fallers, probably because suicidal falls occurred from a higher height as compared to accidental falls [11].

Conversely, Lowenstein et al. proposed that feet-first landing, which is common among jumpers, results in a greater force per unit of area, increasing the likelihood of fracture. When this occurs, the impact force reaching the vital organs may be reduced, due to the absorption of kinetic energy by the lower limbs [21].

Present work did not report a higher distance of fall for jumpers as compared to fallers; nevertheless, clinical data (SBP, percentage of shocked patient in ED, ISS, and need of ETT insertion) showed that jumpers have more severe injuries than fallers.

Mortality, necessity of surgical intervention, ICU admission rate and hospital length of stay support the hypothesis of worse outcomes for jumpers as compared to fallers. In particular, the higher mortality rate is due to the early mortality in ED, while subsequent complications have a minor effect on mortality for jumpers. This might be due to the considerable physiologic reserve of jumpers, who are mostly young adults.

It is evident that the Trauma Registry can be a useful tool to identify populations of patients at high risk for attempting suicide to plan preventive and clinical actions and to optimize the management of these patients.

Basing a study on a trauma registry leads also to some limitation: psychiatric history, occupational and financial conditions of jumpers are not available, and this could limit the identification of a population at risk for suicide for FFH. Furthermore, there is incomplete information about the mechanism of fall, the pre-hospital mortality and residual disability of these patients.

Conclusion

In a Northern Italian area, the population at highest risk for suicide by jumping is composed by middle-aged women and the most common setting is the domestic one. Jumpers show the tendency to the “feet-first landing” and seem to have more severe injuries, worse outcomes and a higher early mortality rate compared to fallers. The Trauma Registry can be a useful tool to identify clusters of patients at high risk for suicidal attempt, with the aim of planning preventive and clinical actions and to optimize the health path of these patients.

References

World Health Organisation. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2014.

World Health Organization. The global burden of disease-estimates for 2000–2012. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015.

Värnik A, Kõlves K, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM et al. Suicide methods in Europe: a gender-specific analysis of countries participating in the “European Alliance Against Depression”. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(6):545–51.

Värnik A, Kõlves K, Allik J et al. Gender issues in suicide rates, trends and methods among youths aged 15–24 in 15 European countries. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(3):216–26.

Choi JH, Kim SH, Kim SP, Jung KY, Ryu JY, Choi SC, Park IC. Characteristics of intentional fall injuries in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:529–34.

ISTAT. Malattie fisiche e mentali associate al suicidio: un’analisi sulle cause multiple di morte; 2017.

Rocos B, Chesse TJ. Injuries in jumpers—are there any patterns? World J Orthop. 2016;7(3):182–7.

Li L, Smialek J. The investigation of fatal falls and jumps from heights in Maryland (1987–1992). Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1994;15(4):295–9.

Rocos B, Acharya M, Chesser TJ. The pattern of injury and workload associated with managing patients after suicide attempt by jumping from a height. Open Orthop J. 2015;9:395–8.

de Pourtalès MA, Hazen C, Cottencin O, Consoli SM. Adolescence, substance abuse and suicide attempt by jumping from a window. Presse Med. 2010;39:177–86.

Dickinson A, Roberts M, Kumar A, Weaver A, Lockey DJ. Falls from height: injury and mortality. J R Army Med Corps. 2012;158:123–7.

Kennedy P, Rogers B, Speer S, Frankel H. Spinal cord injuries and attempted suicide: a retrospective review. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:847–52.

Copeland A. Suicide by jumping from buildings. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1989;10:295–8.

Kontaxakis V, Markidis M, Vaslamatzis G, Ioannidis H, Stefanis C. Attempted suicide by jumping: clinical and social features. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;77:435–37.

Bennewith O, Nowers M, Gunnell D. Effect of barriers on the Clifton suspension bridge, England, on local patterns of suicide: implications for prevention. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:266–67.

American College of Surgeons. 2019. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/ipc/falls.

Teh J, Firth M, Sharma A. Jumpers and fallers: a comparison of the distribution of skeletal injury. Clin Radiol. 2003;58(6):482–6.

Richter D, Hahn MP, Ostermann PA, Ekkernkamp A, Muhr G. Vertical deceleration injuries: a comparative study of the injury patterns of 101 patients after accidental and intentional high falls. Injury. 1996;27:655–9.

Hahn MP, Richter D, Ostermann PA, Muhr G. Injury pattern after fall from great height. An analysis of 101 cases. Unfallchirurg. 1995;98:609–13.

Abel SM, Ramsey S. Pattern of skeletal trauma in suicidal bridge jumpers: a retrospective study from the southeastern United States. Forensic Sc Int. 2013;399.e1–399e5.

Lowenstein SR, Yaron M, Carrero R, Devereux D, Jacobs LM. Vertical trauma: injuries to patients who fall and land on their feet. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18(2):161–5.

Gill JR. Fatal descent from height in New York City. J Forensic Sci. 2001;46:1132–37.

Roy-Camille R, Saillant G, Gagna G, Mazel C. Transverse fracture of the upper sacrum. Suicidal jumper’s fracture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10:838–45.

Stanford RE, Stanford RE, Soden R, Bartrop R, Mikk M, Taylor TK. Spinal cord and related injuries after attempted suicide: psychiatric diagnosis and long-term follow-up. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:437–43.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to deeply thank and express gratitude to ‘Associazione Marco Piazzalunga’- Friends of the Trauma Registry of the Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital of Bergamo, Italy. Their constant financial and intellectual support to the activities of the Trauma Registry was essential for the realization of the current study and for the maintenance of the Trauma Registry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors have read and approved the final draft. All the authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piazzalunga, D., Rubertà, F., Fugazzola, P. et al. Suicidal fall from heights trauma: difficult management and poor results. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 46, 383–388 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01110-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-019-01110-8