Abstract

Purpose

Prophylactic placement of endovascular balloon occlusion catheters has grown to be part of the surgical plans to control intraoperative hemorrhage in cases of abnormal placentation. We performed a systematic literature review to investigate the safety and effectiveness of the use of REBOA during cesarean delivery in pregnant woman with morbidly adherent placenta.

Methods

A systematic review was performed. Relevant case reports and nonrandomized studies were identified by the literature search in MEDLINE. We included studies involving pregnant woman with diagnosis of abnormal placentation who underwent cesarean delivery with REBOA placed for hemorrhage control. MINORS’ criteria were used to evaluate the risk of bias of included studies. A formal meta-analysis was not performed.

Results

Eight studies were included in cumulative results. These studies included a total of 392 patients. Overall, REBOA was deployed in 336 patients. Six studies reported the use of REBOA as an adjunct for prophylactic hemorrhage control in pregnant woman with diagnosis of morbidly adherent placenta undergoing elective cesarean delivery. In two studies, REBOA was deployed in patients already in established hemorrhagic shock at the moment of cesarean delivery. REBOA was deployed primarily by interventional radiologists; however, one study reported a surgeon as the REBOA provider. The results from our qualitative synthesis indicate that the use of REBOA during cesarean delivery resulted in less blood loss with a low rate complications occurrence.

Conclusion

REBOA is a feasible, safe, and effective means of prophylactic and remedial hemorrhage control in pregnant women with abnormal placentation undergoing cesarean delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Morbidly adherent placenta (MAP), which includes accreta, increta, and percreta, is a leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage [1, 2]. MAP becomes clinically problematic at the moment of delivery, since it is associated with an increased risk of major hemorrhage and thus with poor maternal outcomes [3, 4]. In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the multidisciplinary care of these patients [5], and the trauma and acute care surgeon could play a vital role, not only as a “Surgical Rescuer” [6] but also as a fundamental component of the elective surgical care.

The use of endovascular technology in the management of patients with MAP has grown to be part of the surgical plans to control intraoperative bleeding. Recent evidence suggests that prophylactic preoperative placement of balloon catheters in the abdominal vasculature supplying the uterus results in better outcomes among woman with MAP [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Surgical options available to minimize blood loss include proximal occlusion of the internal iliac arteries and occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta.

Recently, there has been renewed interest in REBOA, especially from trauma surgeons. REBOA has reappeared as a safe and effective intervention in the management of torso hemorrhage [16, 17]. Data from a systematic review conducted by Morrison et al. [17] found five conditions in which REBOA has been used: postpartum hemorrhage, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, tumor surgery, traumatic hemorrhage, and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. This review highlighted the feasibility and utility of the prophylactic use of REBOA in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. However, little is known about the clinical effectiveness of the use of REBOA in cases of MAP. We performed a systematic literature review to investigate the safety and effectiveness of the use of an REBOA during cesarean delivery in pregnant woman with morbidly adherent placenta.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [18]. The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. This study is part of a project approved by the institutional review board at la Fundacion Valle del Lili University Hospital in Cali, Colombia (Protocol number 374).

Our PICO strategy was as follows: Patients: pregnant women with diagnosis of morbidly adherent placenta (accreta, increta, and percreta); Intervention: use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) at the moment of cesarean delivery; Comparison: traditional cesarean delivery without REBOA placement/no comparison; Outcomes: Blood loss and REBOA deployment-related complications. For this strategy, the proposed systematic review responded de following questions:

-

1.

What is the role of REBOA in the management of pregnant woman with morbidly adherent placenta?

-

2.

Is there a definitive advantage of REBOA when used in the management of pregnant women with morbidly adherent placenta?

Inclusion criteria

All published case reports and nonrandomized studies without comparison group on aortic balloon occlusion catheters (REBOA) deployed in pregnant woman with morbidly adherent placenta undergoing cesarean delivery were included. In the case of nonrandomized studies with a comparison group, the REBOA group had to be compared to a group of traditional cesarean delivery without aortic occlusion. Articles considered relevant were selected for review. We excluded publications that included patients with other conditions who underwent intravascular aortic balloon occlusion procedures, and those where the occluded artery was not the aorta.

Search methods

A literature search was performed in MEDLINE from inception to February 2017. The following terms were used and combined: “placenta accreta”, “placenta percreta”, “placenta increta”, “abnormal placentation”, “placental diseases”, “balloon occlusion”, “aortic occlusion”, “endovascular procedures”, and “REBOA”. Only articles in English were reviewed.

Study selection and data collection

Two individuals independently assessed the titles and abstracts identified by the searches for potential eligibility, and the full-text articles were retrieved for those that appeared relevant. Relevant studies were reviewed in detail by two investigators (RMN and MPN) who extracted the data. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third independent reviewer (CAO).

The following information was independently extracted using a standardized form: study design, geographic location, authors names, title, objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, REBOA information on arterial access, deployment method, complications, and endovascular providers; definition of outcomes and outcomes measures.

Risk of bias

The internal validity of each nonrandomized study included in this review was critically evaluated for bias according to the methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS) [20, 21], which covers 12 domains through which bias might be introduced into a nonrandomized study. Each domain is scored as 0 (red) if not reported (high risk of bias); 1 (yellow), reported but inadequate (unclear risk of bias); and 2 (green), reported and adequate (low risk of bias).

Data analysis

Data were extracted as presented in individual studies. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software (StataCorp LLC, TX, USA). A formal meta-analysis (quantitative synthesis) was not appropriate because of the quality and heterogeneity of the studies.

Results

Qualitative synthesis

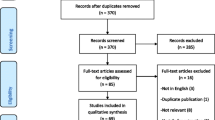

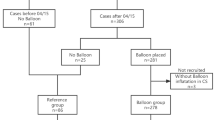

We identified 95 unique records from our searches, of which 14 publications were eligible to be included in our systematic review. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, eight studies were included in our qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1 ).

Included studies were published between 1995 and 2016. These studies included a total of 392 patients (range = 1–392). Studies included were case reports (n = 4) [22,23,24,25], case series (n = 2) [13, 26], and retrospective cohort studies (n = 2) [14, 15] (Table 1 ).

Placenta accreta was the most common diagnosis in the nonrandomized studies. Placenta percreta was diagnosed in 32% of patients (n = 111/347). The abnormal placenta was diagnosed in the prenatal period in six studies [13,14,15, 24,25,26]. On these studies, the diagnostic method of choice was MRI or ultrasound. In two of the case reports included, the abnormal placenta was not diagnosed in the prenatal period, and instead, the diagnosis was made at the moment of cesarean delivery [22, 23].

Overall, REBOA was deployed in 336 cases of MAP. Six studies (two case reports [24, 25], two case series [13, 26], and two retrospective cohort studies [14, 15]) reported the use of REBOA as an adjunct for prophylactic hemorrhage control in pregnant woman with diagnosis of MAP undergoing elective cesarean delivery. In these studies, the REBOA was inserted before the cesarean section. In two case reports [22, 23], REBOA was deployed in pregnant women already in established hemorrhagic shock at the moment of cesarean delivery as a therapeutic method for hemorrhage control.

An interventional radiologist deployed REBOA in seven studies. In these studies, REBOA was inserted by a standard Seldinger technique. One study [22] reported the insertion of REBOA by surgical cutdown and performed by a transplant surgeon. REBOA was inserted through the right femoral artery in five studies [13, 15, 24,25,26]. One study reported the use of the left femoral artery [22] and two studies [14, 23] did not report data about arterial access. REBOA was inflated in zone III of the aorta (infrarenal aorta) in all studies. Fluoroscopy was used to confirm correct REBOA placement in six studies (Table 1).

The REBOA was inflated immediately after fetal delivery and umbilical cord clamping in four studies [13,14,15, 26]. In the reports by Masamoto [25] and Paull [24], the REBOA was inflated when major bleeding began. Three studies reported length of occlusion. Duan et al. [13], Benedetti et al. [14], and Wu et al. [15] reported averages occlusion times of 22, 32, and 23 min, respectively.

Our outcomes of interest were blood loss and REBOA deployment-related complications. Two studies compared (retrospectively) the prophylactic use of REBOA with the traditional cesarean delivery. In these studies, the preoperative placement of a REBOA resulted in lower volumes of estimated blood loss [Panici [14]: REBOA = 950 ml vs. traditional cesarean delivery = 3375 ml; p < 0.001. Wu [15]: REBOA = 921 ml vs. traditional cesarean delivery = 2790 ml; p < 0.001]. Three studies reported data on postoperative complications. In overall, complications likely to be related to the arterial access occurred in two patients [26] (Table 1). No other REBOA-related complications or maternal deaths occurred.

Risk of bias

MINORS criteria [20] were used to assess the risk of bias of the selected articles. Results from the risk of bias assessment are listed in Fig. 2. Case reports were not evaluated for risk of bias as these studies have an inherited high risk of bias.

Discussion

The present systematic review provides clinical information supporting the use of an REBOA for the prevention and management of massive maternal hemorrhage in cases of abnormal placentation. In summary, we found eight studies that reported the use of an REBOA in 336 cases of MAP. Our qualitative synthesis found that REBOA is a feasible option, not only as a therapeutic strategy for hemorrhage control in established hemorrhagic shock but also for prophylactic hemorrhage control in pregnant woman undergoing elective cesarean delivery.

Two studies [14, 15] included in this systematic review provided a head-to-head comparison between the traditional cesarean delivery and cesarean delivery with prophylactic zone III aortic REBOA occlusion. These studies showed that REBOA is a safe and effective strategy to control major bleeding and results in lower values of blood loss in cases of MAP. The previous studies evaluating the use of endovascular balloon occlusion catheters for the occlusion of the iliac, uterine, or hypogastric arteries observed inconsistent results on whether these devices could positively affect maternal outcomes, especially those related to perioperative hemorrhage [7, 8, 10, 11, 27, 28]. Although the placement of intravascular balloon occlusion catheters has been performed at several levels of the pelvic vasculature, the occlusion of these arteries could result in suboptimal hemostasis, as there is a rich collateral circulation within the pelvic vasculature [29]. To date, one study [30] has tested the efficacy of temporary abdominal aortic occlusion compared to internal iliac artery occlusion for the management of placenta accreta. This study found that temporary abdominal aortic balloon occlusion resulted in better clinical outcomes with less blood loss and blood transfusion.

The present review found that the femoral artery was the preferred vessel used to access the aorta. The femoral artery is a larger caliber artery that allows the introduction of larger size catheters; therefore, femoral access is the preferred vascular access for REBOA insertion [31]. As for access methods, only one study reported the insertion of REBOA through open-cutdown. Now, concerning the former, data from the AAST prospective aortic occlusion for resuscitation in trauma and acute care surgery (AORTA) registry [31] found that REBOA insertion by open-cutdown was necessary in 50% or more of cases. In this report, the patients were trauma victims and primarily hypotensive in whom percutaneous insertion was difficult. In contrast, most of the patients (n = 390/392) included in our qualitative synthesis were without signs of shock at the moment of cesarean delivery. Therefore, in pregnant women going to elective cesarean delivery, percutaneous access seems to be a safe and feasible mode of vascular access for REBOA insertion. However, femoral access via cutdown should be reserved for pregnant women in established hemorrhagic shock as this method has shown the most favorable success rates in hypotensive patients [17].

REBOA deployment was guided by fluoroscopy in eight studies, and two studies reported a clinical method of deployment. Although fluoroscopy was the most common method, several reports have shown that REBOA deployment can be performed using only external landmarks without any imaging [31,32,33] (Fig. 3 ). Moreover, previous research on the utility of fluoroscopy in obtaining common femoral artery access has demonstrated that its use does not increase the probability of successful femoral artery cannulation [34, 35].

One study included in this systematic review reported the insertion of the REBOA performed by a surgeon [22]. Historically, backgrounds of endovascular providers have included cardiologists, vascular surgeons, and interventional radiologist. Although interventional radiologists were the most common endovascular providers in this systematic review, the experience from trauma reports has demonstrated that trauma and acute care surgeons can successfully perform REBOA maneuver. In addition, there are well-recognized courses designed to provide fundamental endovascular skills for surgeons [36, 37]. Therefore, the trauma and acute care surgeon could be introduced into the multidisciplinary teams for the care of patients with MAP as the REBOA provider.

This systematic review provided clinical information supporting the use of an REBOA in cases of MAP. However, there are still unanswered questions. First, although our systematic review reported a low rate of adverse events among included patients, studies from Japan [38] suggest that REBOA may be associated with serious adverse events, especially artery thrombosis, and limb ischemia. As the pregnancy is a state characterized by many physiological and hematological changes, further studies on adverse events, which take these variables into account, will need to be undertaken. Second, future studies should evaluate the effect of including trauma surgeons with added endovascular skills’ qualifications into the multidisciplinary teams for the care of patients with MAP.

Conclusions

REBOA is a safe and effective intervention to be performed in patients with MAP. This systematic review provided information on the feasibility and effectiveness of REBOA, for both, as a remedial and therapeutic strategy for hemostasis support during cesarean delivery of patients with MAP. As the landscape of the trauma surgeon has changed over the last years [6, 39], our qualitative synthesis results could add to further progress in the fields of acute care surgery.

References

Bauer ST, Bonanno C. Abnormal placentation. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:88–96. (Elsevier).

ACOJ. Committee Opinion No. 529: placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:207–11. http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2012/07000/Committee_Opinion_No__529___Placenta_Accreta_.42.aspx. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol Elsevier. 2005;192:1458–61.

Hudon L, Belfort MA, Broome DR. Diagnosis and management of placenta percreta: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53(8):509–17.

Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, Masheter C, Soisson AP, Dodson M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):331–7.

Kutcher ME, Sperry JL, Rosengart MR, Mohan D, Hoffman MK, Neal MD, et al. Surgical rescue: The next pillar of acute care surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82. http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2017/02000/Surgical_rescue___The_next_pillar_of_acute_care.6.aspx. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Ballas J, Hull AD, Saenz C, Warshak CR, Roberts AC, Resnik RR, et al. Preoperative intravascular balloon catheters and surgical outcomes in pregnancies complicated by placenta accreta: a management paradox. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(3):216.e1–5. (Elsevier Inc).

Cesar F, Mario C, Kondo M, Oliveira W, De S Jr. Perioperative temporary occlusion of the internal iliac arteries as prophylaxis in cesarean section at risk of hemorrhage in placenta accreta. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34(4):758–64. doi:10.1007/s00270-011-0166-2.

Cali G, Forlani F, Giambanco L, Luisa M, Vallone M, Puccio G, et al. Prophylactic use of intravascular balloon catheters in women with placenta accreta, increta and percreta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;179:36–41. (Elsevier Ireland Ltd).

Teixidor Viñas M, Chandraharan E, Moneta MV, Belli AM. The role of interventional radiology in reducing haemorrhage and hysterectomy following caesarean section for morbidly adherent placenta. Clin Radiol. 2014;69:e345–e51. (Elsevier).

Tan CH, Sheah K, Kwek K, Wong K, Tan HK, et al. Perioperative endovascular internal iliac artery occlusion balloon placement in management of placenta accreta. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(5):1158–63.

Chou MM, Kung HF, Hwang JI, Chen WC, Tseng JJ. Temporary prophylactic intravascular balloon occlusion of the common iliac arteries before cesarean hysterectomy for controlling operative blood loss in abnormal placentation. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;54:493–8. (Elsevier).

Duan X-H, Wang Y-L, Han X-W, Chen Z-M, Chu Q-J, Wang L, et al. Caesarean section combined with temporary aortic balloon occlusion followed by uterine artery embolisation for the management of placenta accreta. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:932–7. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000992601500104X. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Panici PB, Anceschi M, Borgia ML, Bresadola L, Masselli G, Parasassi T, et al. Intraoperative aorta balloon occlusion: fertility preservation in patients with placenta previa accreta/increta. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2012;25:2512–6. 10.3109/14767058.2012.712566. (Taylor & Francis).

Wu Q, Liu Z, Zhao X, Liu C, Wang Y, Chu Q, et al. Outcome of pregnancies after balloon occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta during caesarean in 230 patients with placenta praevia accreta. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:1573–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5052309/. (New York: Springer US). Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Biffl WL, Fox CJ, Moore EE. The role of REBOA in the control of exsanguinating torso hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:1054–8.

Morrison JJ, Galgon RE, Jansen JO, Cannon JW, Rasmussen TE, Eliason JL, et al. A systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;80:324–34.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ Br Med J. 2015;349. http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7647.abstract. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. (Public Library of Science).

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–6. (Blackwell Science Ptd).

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JSW, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:2–10.

Bell-Thomas SM, Penketh RJ, Lord RH, Davies NJ, Collis R. Emergency use of a transfemoral aortic occlusion catheter to control massive haemorrhage at caesarean hysterectomy. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;110:1120–2. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.01133.x. (Blackwell Science Ltd).

Usman N, Noblet J, Low D, Thangaratinam S. Intra-aortic balloon occlusion without fluoroscopy for severe postpartum haemorrhage secondary to placenta percreta. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2017;23:91–3. 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.06.006. (Elsevier).

Paull JD, Smith J, Williams L, Davison G, Devine T, Holt M. Balloon occlusion of the abdominal aorta during caesarean hysterectomy for placenta percreta. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1995;23:731–4.

Masamoto H, Uehara H, Gibo M, Okubo E, Sakumoto K, Aoki Y. Elective use of aortic balloon occlusion in cesarean hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;67:92–5.

Wei X, Zhang J, Chu Q, Du Y, Xing N, Xu X, et al. Prophylactic abdominal aorta balloon occlusion during caesarean section: a retrospective case series. Int J Obstet Anaesth. 2016;27:3–8. (Elsevier Ltd).

Salim R, Chulski A, Romano S, Garmi G, Rudin M, Shalev E. Precesarean prophylactic balloon catheters for suspected placenta accreta A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:1022–8.

Shrivastava V, Nageotte M, Major C, Haydon M, Wing D. Case-control comparison of cesarean hysterectomy with and without prophylactic placement of intravascular balloon catheters for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:1–5.

Chait A, Moltz A, Nelson JH, The collateral arterial circulation in the Pelvis. Am J Roentgenol. 1968;102:392–400. 10.2214/ajr.102.2.392. (American Roentgen Ray Society).

Wang Y-L, Duan X-H, Han X-W, Wang L, Zhao X-L, Chen Z-M, et al. Comparison of temporary abdominal aortic occlusion with internal iliac artery occlusion for patients with placenta accreta—a non-randomised prospective study. Vasa. 2016. 10.1024/0301-1526/a000577. (Hogrefe AG).

DuBose JJ, Scalea TM, Brenner M, Skiada D, Inaba K, Cannon J, et al. The AAST prospective aortic occlusion for resuscitation in trauma and acute care surgery (AORTA) registry: data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:409–19. http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma/Fulltext/2016/09000/The_AAST_prospective_Aortic_Occlusion_for.1.aspx. Accessed 23 Feb 2017.

Linnebur M, Inaba K, Haltmeier T, Rasmussen TE, Smith J, Mendelsberg R, et al. Emergent non-image-guided resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) catheter placement: a cadaver-based study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:453–7.

Scott DJ, Eliason JL, Villamaria C, Morrison JJ, Houston R, Spencer JR, et al. A novel fluoroscopy-free, resuscitative endovascular aortic balloon occlusion system in a model of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:122–8.

Abu-Fadel MS, Sparling JM, Zacharias SJ, Aston CE, Saucedo JF, Schechter E, et al. Fluoroscopy vs. traditional guided femoral arterial access and the use of closure devices: a randomized controlled trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74:533–9. (Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company).

Huggins CE, Gillespie MJ, Tan WA, Laundon RC, Costello FM, Darrah SB, et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial of the use of fluoroscopy in obtaining femoral arterial access. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009;21:105–9.

Villamaria CY, Eliason JL, Napolitano LM, Stansfield RB, Spencer JR, Rasmussen TE. Endovascular skills for trauma and resuscitative surgery (ESTARS) course: curriculum development, content validation, and program assessment. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:929–35. (discussion 935–6).

Brenner M, Hoehn M, Pasley J, Dubose J, Stein D, Scalea T. Basic endovascular skills for trauma course: bridging the gap between endovascular techniques and the acute care surgeon. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:286–91.

Saito N, Matsumoto H, Yagi T, Hara Y, Hayashida K, Motomura T, et al. Evaluation of the safety and feasibility of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:897–904.

Ciesla DJ, Moore EE, Cothren CC, Johnson JL, Burch JM. Has the trauma surgeon become house staff for the surgical subspecialist? Am J Surg. 2006;192:732–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

RMN, MFE, MPN, FR, PF, JDC, and CAO comply with the ethical guidelines for authorship and publishing in the European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. This Systematic Review contains images of a patient with MAP that underwent prophylactic REBOA placement. Informed consent was obtained from the participant who appears in the pictures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Manzano-Nunez, R., Escobar-Vidarte, M.F., Naranjo, M.P. et al. Expanding the field of acute care surgery: a systematic review of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in cases of morbidly adherent placenta. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 44, 519–526 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0840-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-017-0840-4