Abstract

Background

Minor head injury is one of the major diagnoses requiring management in emergency departments (ED) but its squeals are not well studied in our country.

Objective

To describe the prevalence of post-concussive syndrome and its impacts on life activities, up to 6 months of follow-up, among patients having a minor head injury and discharged from ED.

Methods

A prospective bi-centric study including adults having a minor head trauma and consenting to be followed up to 6 months after discharge. The Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ) was used at baseline, after 15 days, at 1 month, at 3 months and at 6 months post-injury to assess concussive symptoms. We also used the Rivermead Head Injury Follow-up Questionnaire (RHFUQ) to describe impacts of minor head trauma on life activities.

Results

There were 130 consenting patients at baseline interview. Proportion of patients describing post-concussive symptoms at baseline was 71/130. At 6 months of follow-up, post-concussive syndrome was diagnosed among 21.4 % of participants. Sustaining symptoms at 6 months post-injury were mainly anger and irritability (12.5 %). Correlations between high RPQ sum rates since 15 days’ post-injury call and the sum total rates of RHFUQ were significant. The major significant impact of minor head trauma at 6 months of follow-up was among domestic activities.

Conclusion

The two most important findings of this study were the huge proportion of patients having minor head injury and discharged from ED without any explanation of possible symptoms after head trauma and the unknown impacts on life activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Minor head traumas are a major cause of consultation at emergency departments (EDs) around the world [1, 2]. They are accounting for 85 % of all brain injuries [3]. Many definitions of minor head trauma are proposed. WHO classification requires the presence of one of four criteria (confusion, loss of conscious less than 30 min, amnesia less than 24 h, neurological abnormalities) among a patient with a Glasgow coma scale at 13 or more. French Society of emergency medicine (SFMU) defines them by a Glasgow coma scale between 13 and 15 points [2]. Commonly, these patients have a favourable outcome [4]. However, a subgroup of these discharged patients suffered from symptoms many months after trauma. These symptoms are regrouped in a pathological entity called post-concussive syndrome which defines the poor outcome of minor head injury. In fact, post-concussive symptoms can be costly and debilitating to the patients and the whole system care [3]. Prevalence of this syndrome is very variable in studies and its impact on social, familial and professional quality of life is not well known in our country. Given the paucity of research on post-concussive syndrome in our country, we decided to realize this study to address what are the symptoms described by these patients until 6 months post-injury and what are the consequences on social and familial life.

Methods

Clinical setting

The study population consisted of consecutive patients diagnosed with minor head injury presenting to the emergency department of Sfax or Deguach in Tunisia between September 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014. A phone follow-up was then realized up to 6 months post-injury. Based on guidelines of the French society of emergency medicine (SFMU), minor head trauma was defined as Glasgow coma scale between 13 and 15 points [2]. The hospital of Sfax is an academic tertiary one while Deguach hospital is the unique serving hospital of a village in the southwest of Tunisia. The study was conducted in both centres by a full-time physician with certification in Emergency medicine from the University of Medicine of Sfax in Tunisia.

Inclusions and exclusions

Patients were eligible for the study if they satisfied the SFMU definition of mild head trauma (GCS 13 or more) [2] during the management at the ED, were aged 18 or more and provided an informed consent to participate and to be called by phone after their discharge. Patients were excluded if their GCS was under than 13, were aged under than 18 years and refused to be contacted for the research purposes or sustained missing to call up to 3 days after injury.

Patients’ enrolment and follow-up

Potential study participants were identified via the following method. We explained the aims of the study to all ED’s physicians in the two hospitals. They had to write phone number of each patient having head trauma on the medical file and informed the patient that he will perhaps be phoned by a doctor after his discharge. No changes in patients’ treatments were required. CT scan was not required for all patients; ED’s physician had to realize CT scan if it was judged necessary. The following day, patients’ files were reviewed by a coordinator in each hospital which identified eligible patients and then attempted to contact them by telephone. During this initial telephone contact, the researcher explained to the patient the aims of the study and obtained his oral consent to be called up to 6 months post-injury. Then, he confirmed the accuracy of demographic information contained in the medical record, asked additional questions about the patient’s injury history and asked questions of the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ) [5, 6]. Follow-up telephone calls were scheduled and completed by the same researcher at 15 days post-injury, 30 days post-injury, 3 months post-injury and 6 months post-injury. Since the call of 1-month post-injury, the researcher added to his questions those of the Rivermead Head Injury Follow-up Questionnaire (RHFUQ) [7, 8]. The two questionnaires were used without any modification.

Instruments and measures

Severity of concussive symptoms was assessed by the RPQ and disabilities were assessed using the RHFUQ. We realized a translation of the RPQ and RHFUQ from English to Arabic by two persons and a retranslation from Arabic to English. Reliability of the used questionnaires was assessed by analysing the internal consistency of items through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The value of 0.70 was adopted as the lower limit of consistency [9]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.95 for RPQ and 0.71 for RHFUQ.

The severity of each symptom as assessed by the RPQ was rated as 0 (not experienced at all), 1 (same as before injury), 2 (a mild problem), 3 (a moderate problem), or 4 (a severe problem) [5, 6]. Symptoms were viewed individually and then grouped into the categories of somatic (headache, dizziness, fatigue, blurred vision, etc.), emotional (irritability, depression, frustration), or cognitive symptoms (poor memory, poor concentration, slower thinking). RPQ score varies between 0 and 52 points. At 1 month or more, an RPQ score of ≥2 on an individual symptom was interpreted as the presence of a concussive symptom. If a patient had more than 3 of 16 possible symptoms, this was used to indicate presence of “post-concussive syndrome” [5, 6].

The ten RHFUQ’s items cover social and domestic activities, work and relations with friends and family. The participants are asked to rate changes in their abilities compared with prior to injury. The answers range from 0 = no change to 4 = a very marked change. At 1, 3 and 6 months post-injury interviews, the sum totals for each RHFUQ questionnaire were obtained by adding ratings of 1, 2, 3, and 4 for the 10 score items [7].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 18.0 for Windows. Data are reported as numbers and rates. Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate subjects’ demographic characteristics as well as their perceived importance and priority of immediate needs. Spearman correlation was realized to describe relationship between the RHFUQ’s sum and each item of the same questionnaire and the sum total of RPQ. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Demographic features of the sample

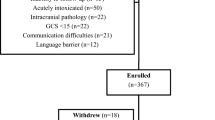

There were 1052 patients eligible to the study in the first centre and 102 patients eligible in the second centre. A total of 130 patients completed the baseline interview. Enrolment of patients was as shown in Fig. 1. All missing patients were called at each interview of follow-up but all of them sustained uncontactable. Men were 1.6 times more frequent than women in our sample. Table 1 shows demographic features of participants, type of injury and the point of impact on head as described in patient emergency file. CT scan was done to 5 patients with headaches and vomiting at emergency. Their GCS were at 13 for one patient, 14 for 2 patients and 15 for the 2 remaining patients. These 5 patients were with a normal CT scan.

Post-concussive syndrome

At the baseline interview, 71 patients were diagnosed having a post-concussive syndrome (54.6 %). This proportion had progressively decreased to be at 21.4 % at the last interview (Table 2). Headaches were the major reported symptom at the baseline interview (56.9 %) while anger and irritability were the main symptoms at 6 months of follow-up (12.5 %). Somatic symptoms were the most reported at baseline call while emotional symptoms were the most important symptoms described at 6 months post-injury (Table 2).

Impact of minor head trauma on life activities according to RHFUQ

One month after the head trauma, there was an impact on usual activities among 37.1 % of participants. This proportion decreased to 16.1 % at the last call (Table 3). Table 3 shows that all the items of the RHFUQ were reliable at 1, 3 and 6 months post-injury. At 6 months, the items with the lowest significant coefficient were the questions on conversation with two or more persons and domestic activities especially with the partner. Item on previous workloads was the most reported at 1, 3 and 6 months post-injury’s interviews (Table 3). Since 15 days post-injury, there was a significant positive correlation between sum total ratings on the RHFUQ with those obtained on the RPQ. Spearman’s rank coefficients were, respectively, 0.22, 0.35, 0.51 and 0.81 at 15 days, 1, 3 and 6 months post-injury interviews. The value of p was 0.03 at 15 days’ interview and less than 0.0001 at the remaining ones.

Discussion

The sequelas of minor had injuries on live activities after discharge is still under discussion. This is a prospective study concerning 130 patients with mild TBI and follow-ups till sixth month using the RPQ.

The two major findings of this study are the high rate of post-concussive symptoms (21.4 %) and their consequent impacts on the life activities up to 6 months post-injury. All these patients were discharged without any explanation of possible post-concussive symptoms or how to be followed after their trauma. More than half of the participants reported headaches at baseline interview and somatic symptoms were the most reported at the first call. At 6 months post-injury, sustaining symptoms were especially emotional ones (anger and irritability). This high prevalence of post-concussive syndrome is important to make physicians aware of these disturbances. ED caregivers should have trainings about this syndrome to be able to anticipate and to explain to patients how these symptoms will occur and progress. In Tunisia, there are not yet a referral follow-up of patients discharged from EDs with minor head trauma.

Results of this study coincide with those realized in other countries. The proportion of patients having a post-concussive syndrome at baseline interview (54.6 %) tallies with findings of literature. Actually, post-concussive syndrome is diagnosed after minor head trauma among 34–84 % of patients [10–12]. As we found, the major symptoms described by these patients are headaches, vertigo, fatigue, concentration and memory disturbances, anxiety, feeling depressive irritability and light or noise sensitivity [13–22]. Typically, post-concussive symptoms decrease progressively and recover in 80–100 % of cases 1 week after injury [23–25]. Sustaining symptoms after 1 month of follow-up are reported by 3–15 % of patients [25, 26]. In our study, 21.4 % of patients had post-concussive syndrome at 6 months’ interview. The decline of somatic symptoms and the development of emotional and cognitive symptoms are well described by most of the studies [3, 27]. These trends are found among our patients. Sustaining post-concussive syndrome is usually associated with poor outcome of minor head traumas because of its impacts on life activities. This association was demonstrated in many studies using RHFUQ. Crawford found that, as indicated by the RPQ, more significant the impairment is, the greater the disability indicated by the RHFUQ [7]. We also found this correlation in our sample. Moreover, our results suggest that an early diagnosis of post-concussive syndrome 15 days after trauma is useful to detect patients with a higher risk of having more difficulties in life activities.

Several methodological considerations are to consider. Firstly, the small size of our sample limits the generalization of the results. Moreover, included patients are those how had accepted to be interviewed, thereby, non-participating patients were probably different from participating ones. We could not realize comparison of demographic features between study population and originally one because medical files are not computerized in study centres. The second limit of this study was the different size of both centres (100 vs. 30), this bias explains the lack of comparison between urban and rural populations. The third limit was the lack of imaging and psychological evaluation after discharge of patients having sustaining complaints a 6 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

Our study is the first to investigate post-concussive syndrome up to 6 months post-injury in an Arabic sample. Its prevalence among our patients tallied with previous studies in other cultures. Moreover, we found many impacts on life activities especially domestic ones. Training caregivers at emergency departments is necessary to improve follow-up of patients having minor head trauma and to detect those with an early post-concussive syndrome to reduce impacts on life activities. We append that creation of a multidisciplinary referral structure to follow-up patients discharged from emergency departments with a minor head trauma is an urgent decision to make in our country. This may prevent development of post-concussive syndrome and its possible delayed sequelae.

References

Tazarourte K, Macaine C, Didane H et al. Traumatisme crânien non grave. EMC, Médecine d’urgence. Ed Masson, Paris, 2007. 25-200-C-10.

Traumatisme crânien léger (score de Glasgow de 13 à 15): triage, évaluation, examens complémentaires et prise en charge précoce chez le nouveau-né, l’enfant et l’adulte. Société française de médecine d’urgence. E. Jehlé, D. Honnart, C. Grasleguen et al. Ann Fr Med Urgence. 2012 2;199–214.

Cunningham J, Brison R, Pickett W. Concussive symptoms in emergency department patients diagnosed with minor head injury. J Emerg Med. 2011;40(3):262–6.

Lannsjö M, Borg J, Björklund G, et al. Internal construct validity of Rivermead post-concussion symptoms questionnaire. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:997–1002.

King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, et al. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J Neurol. 1995;242:587–92.

Moss NEG, Crawford S, Wade DT. Post-concussion symptoms: is stress a mediating factor? Clin Rehabil. 1994;8:149–56.

Crawford S, Wenden FJ, Wade DT. The Rivermead head injury follow up questionnaire: a study of a new rating scale and other measure to evaluate outcome after head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60:510–4.

Ruff RM, Levin HS, Marshall LF. Neurobehavioral methods of assessment and the study of outcome in minor head injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1986;1:43–52.

Bland MJ, Altman PG. Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314:193–4.

Cicerone KD, Kalmar K. Persistent postconcussion syndrome: the structure of subjective complaints after mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1995;10:1–17.

Van der naalt J, Van Zomeren AH, Sluiter WJ, et al. One year outcome in mild to moderate head injury: the predictive value of acute injury characteristics related to complaints and return to work. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:207–13.

MacKenzie S, Pless IB. CHIRPP: Canada’s principal injury surveillance program. Inj Prev. 1999;5:208–13.

Ramos-Zuniga R, Gonzalez-de la Torre M, Jimenez-Maldonad M et al. Postconcussion syndrome and mild head injury: the role of early diagnosis using neuropsychological tests and functional magnetic resonance/spectroscopy. World Neurosurg. 2014. [article inpress].

Evans RW. The postconcussion syndrome: 130 years of controversy. Semin Neurol. 1994;14:32–9.

Binder LM. Persisting symptoms after mild head injury: a review of the postconcussive syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1986;8:323–46.

Bruns JJ Jr, Jagoda AS. Mild traumatic brain injury. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:129–37.

Evans RW. The postconcussion syndrome and the sequelae of mild head injury. Neurol Clin. 1992;10:815–47.

Evans RW. The postconcussion syndrome and whiplash injuries: a question and answer review for primary care physicians. Prim Care. 2004;31:1–17.

Margulies S. The postconcussion syndrome after mild head trauma: is brain damage overdiagnosed? Part 1. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7:400–8.

Niogi SN, Mukherjee P, Ghajar J, et al. Extent of microstructural white matter injury in postconcussive syndrome correlates with impaired cognitive reaction time: a 3T diffusion tensor imaging study of mild traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:967–73.

Perea-Bartolome MV, Ladera-Fernandez V, Morales-Ramos F. Mnemonic performance in mild traumatic brain injury. Rev Neurol. 2002;35:607–12.

Szymanski HV, Linn R. A review of the postconcussion syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22:357–75.

Arciniegas DB, Anderson CA, Topkoff J, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury: a neuropsychiatric approach to diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. Neuropsychiatry Dis Treat. 2005;1:311–27.

Carroll L, Cassidy J, Peloso P, et al. Prognosis for mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO collaborating centre task force on mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med 2004;(43 Suppl):84–105.

McCrea M, Iverson GL, McAllister TW, et al. An integrated review of recovery aftermild traumatic brain injury (MTBI): implications for clinical management. Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;23:1368–90.

McLean S, Kirsch N, Tan-Schriner Ch, et al. Health status, not head injury, predicts concussion symptoms after minor injury. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:182–90.

Stulemeijer M, Vos P, Bleijenberg G, et al. Cognitive complaints after mild traumatic brain injury: things are not always what they seem. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:637–45.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors (Olfa Chakroun-Walha, Imen Rejeb, Mariem Boujelben, Kamilia Chtara, Achraf Mtibaa, Hichem Ksibi, Adel Chaari, Mounir Bouaziz and Noureddine Rekik) declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chakroun-Walha, O., Rejeb, I., Boujelben, M. et al. Post-concussive syndrome after mild head trauma: epidemiological features in Tunisia. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 43, 747–753 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-016-0656-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-016-0656-7