Abstract

Background and Purpose

Vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke (VBOS) is innately associated with high morbimortality despite advances in endovascular thrombectomy (EVT). Nonetheless, notable outcome dissimilarities exist between angiographically categorized stroke subtypes. We aim to evaluate potential differences concerning clinical angiographic outcomes among etiological subtypes of VBOS based on the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed prospective EVT databases at two tertiary care stroke centers for consecutive patients with VBOS who had preinterventional MRI and underwent EVT from January 2015 to December 2019. We identified three groups: large artery atherosclerosis (LAA), cardioembolic stroke (CES), and embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS). The primary endpoints were the rates of poor outcome (identified as 90-day modified Rankin scale score of 3–6) and mortality, while the secondary endpoint included the rates of incomplete reperfusion (identified as modified treatment in cerebral infarction scale mTICI 0–2b), and periprocedural symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. We evaluated the association between the etiology and clinical angiographic outcomes through stepwise logistic regression analysis.

Results

Out of 1823 patients, 139 (91 men; median age, 69 (61–76) years) with VBOS were qualified for the final analysis with incidence as follows: LAA (41%, n = 57), CES (35%, n = 48), and ESUS (24%, n = 34). Overall, incomplete reperfusion was realized in 41% (57/139) of the patients, a poor outcome in 65% (90/139), and mortality in 40% (55/139). Longer puncture to reperfusion interval (aOR 1.0182 [95% CI: 1.008–1.029]; p < 0.001) and utilization of combined aspiration-retriever technique (aOR 0.1998 [95% CI: 0.066–0.604]; p = 0.004) were associated with a greater likelihood of incomplete reperfusion (mTICI 0–2b) irrespective of the stroke etiology. After adjustment for confounding factors in the regression analysis, ESUS was an independent predictor of poor outcome (aOR 5.315 [95% CI: 1.646–17.163]; p = 0.005) and mortality (aOR 4.667 [95% CI: 1.883–11.564]; p < 0.001) at 90 days following EVT.

Conclusion

The functional outcome following EVT for VBOS might depend on stroke etiology. According to our results, ESUS seems to be associated with the worst outcome, which needs further investigation to tailor the appropriate therapeutic plan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke (VBOS) constitutes 1% of all ischemic stroke and 5% of large vessel occlusive stroke. Nevertheless, they are associated with detrimental outcomes in about 80% of conservatively treated patients despite advances in endovascular treatment and postinterventional care [1, 2]. A recent meta-analysis of prognostic factors in posterior circulation stroke has correlated concordant comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and prior cerebrovascular events, with the poor outcome following endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) [3].

Complete reperfusion might be considered the strongest predictor of a good outcome in conjunction with initial stroke severity, intravenous tPA (tissue-type plasminogen activator) administration, and combined aspiration-retriever thrombectomy strategy [4, 5]. Likewise, baseline radiological characteristics inclusive of lower posterior circulation Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography score (PC-ASPECTs) and reduced posterior circulation collateral score (PC-CS) have been signified as independent predictors of functional dependence in several observational studies [6,7,8].

Comprehensive acquaintance with the etiology of VBOS might help design a tailored therapeutic strategy that would instigate a good outcome; however, to our knowledge, scanty articles have elucidated the dissimilarities between the various etiopathological mechanisms of stroke. Furthermore, prior studies have customarily categorized the stroke etiology on a radio-angiographic basis, with disregard to the clinical context in intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (ICAS) with in situ thrombosis, Tandem steno-occlusive stroke (TSS), and embolic-related stroke commingle cardioembolic stroke (CES) and embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) mechanisms in the same shell [9, 10].

We hypothesized that cardinal comorbidities, procedural perspectives, and clinical angiographic outcome characteristics would differ between ESUS, its potential angiographic mimic, CES, and large artery atherosclerosis (LAA). This study aimed to investigate the impact of stroke etiology based on the trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment (TOAST) [11] criteria on the 90-day functional outcome (as assessed by modified Rankin scale [mRS]) and final reperfusion rate (as assessed by modified treatment in cerebral infarction, mTICI scale) in VBOS patients who underwent EVT following a thorough evaluation by MRI and time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (TOF-MRA).

Material and Methods

Ethics and Data Availability Statement

The institutional review board approved the use of patient data for this research protocol and written informed consent was waived based on the retrospective study design. The corresponding author will provide anonymized individual participant data upon reasonable request.

Patient Selection

Retrospectively, we reviewed prospectively collected registries of all consecutive acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent EVT at two tertiary care academic institutions from January 2015 to December 2019. We initially included patients who presented with acute neurological symptoms subsequent to intracranial VBOS as identified by MRI, TOF-MRA, and underwent EVT aided by newer generation clot-retriever devices. We excluded patients who underwent computed tomography as the only first-line imaging modality before EVT or those with lone posterior cerebral artery (PCA) occlusion. Furthermore, we excluded one patient with essential thrombocythemia and two with intracranial dissection after interpretation of coagulation tests (complete blood count, platelets count, international normalized ratio, partial thromboplastin time), baseline MRI and angiographic images. Fig. 1 illustrates the patient inclusion flowchart.

From the clinical records, we retrieved baseline patient characteristics encompassing age, sex, cerebrovascular comorbidities, prior anti-aggregant therapy, glucose level, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, administration of intravenous tPA, and stroke severity on admission as assessed by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score.

Time of stroke onset was recorded per witnessing, or last time known well if the exact time was obscure. The baseline infarct extent as evaluated by PC-ASPECTs was derived from prethrombectomy imaging. The thrombus location obtained from the initial cerebral angiogram was assorted into intracranial vertebral artery (VA; V4 segment with aplastic or non-contributive contralateral VA); proximal basilar artery (BA; from vertebrobasilar junction to the origin of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery); middle BA (between the origins of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and the superior cerebellar artery) and distal BA (distal to the origin of the superior cerebellar artery) occlusion.

Classification of the Stroke Mechanism

All patients underwent duplex ultrasonography of cervical vessels, TOF-MRA in concurrence with gold-standard angiography, 24‑h Holter electrocardiogram monitoring in conjunction with a transthoracic echocardiogram, and complementary transesophageal echocardiography if deemed necessary, based on the gravity of patients’ clinical condition. Stroke etiology was categorized as defined by the TOAST criteria at the end of the standard etiological work-up by an expert interdisciplinary consensus blinded to functional outcomes.

We considered stroke to be of atherosclerotic origin (LAA; group 1) based on the presence of moderate or severe (≥ 50%) underlying fixed focal basilar stenosis at the target occlusion site with subsequent flow limitation or reocclusion tendency despite successful reperfusion (customarily known as ICAS) or presence of a steno-occluded segment in the extracranial vertebral artery with more than 70% luminal reduction in line with the impaired distal flow (conventionally known as TSS). Cardioembolic stroke (CES; group 2) was diagnosed in patients with clean non-atherosclerotic cerebral vasculature and harboring any of the following: valvular and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, infective endocarditis, left atrial dilatation with in situ thrombosis, global hypokinesia with apical akinesia, mitral or aortic valve replacement, patent foramen ovale with an interatrial septum, and dilated cardiomyopathy. Patients with neither alleged high-risk cardioembolic source nor culprit stenotic lesion that could be set forth on the angiography were designated to have ESUS (group 3).

Outcome Measures

The primary endpoints were the rates of poor outcome (identified as 90-day modified Rankin scale score of 3–6) and mortality, while secondary endpoints included the rates of incomplete reperfusion (identified as modified treatment in cerebral infarction scale mTICI 0–2b) and periprocedural symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. We determined functional neurological outcomes through structured face-to-face interviews employing the mRS score at 90 days, which was dichotomized into good (mRS, 0–2) or poor (mRS score, 3–6) outcomes. All neurological examinations were performed by board-certified, experienced vascular neurologists.

Reperfusion status was evaluated on the last angiogram in compliance with the mTICI scale, whereas successful and complete reperfusion were demarcated as mTICI grade 2b–3 and mTICI grade 2c–3, respectively. Following previous results [5], which demonstrated that complete rather than successful reperfusion was significantly predictive of the outcome in BAO, only incomplete reperfusion (mTICI 0–2b) was fatherly analyzed in our study. We evaluated non-contrast 24‑h postprocedural control CT for intracerebral hemorrhage, which was classified as symptomatic (sICH) if coupled with a drop of more than 4 points on the NIHSS scale, conforming to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study classification (ECASS III) [12]. Data concerning reperfusion grades and postprocedural control imaging were analyzed based on site interpretation and were not adjudicated by a central core laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

The baseline characteristics, procedural details, and outcomes were compared among the culprit etiopathological mechanisms of stroke. Continuous variables were reported as mean (SD) or median (IQR), while categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Between groups, comparisons for continuous variables were made with the Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney U test, or ANOVA, and Kruskal-Wallis test based on the normality of the data distribution. Categorical variables were compared by χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. An initial univariate analysis was performed to identify predictors of the incomplete reperfusion (mTICI 0–2b), the poor outcome (mRS 3–6), and the mortality. Backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was utilized to identify the most important predictors of the incomplete reperfusion, poor outcome (mRS 3–4, mRS 3–6), and mortality at 90 days following thrombectomy. The threshold for variable entry in the model was p-value < 0.10. The stopping rule was attained when all remaining variables in the model showed a p-value less than 0.05. Regression models used maximum step-halving. At each iteration, the step size is reduced by a factor of 0.5 until the log-likelihood increases or maximum step-halving is reached. All statistical tests were 2‑sided, and the significance level was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 139 consecutive patients with VBOS, who were primarily imaged with MRI and treated with EVT, were included in the final analysis. The median age was 69 years (range 61–76 years), with a median admission NIHSS score of 15 (9–24). Cardioembolic stroke (CES 48/139 patients [35%]) was the most frequent stroke subtype, followed by ICAS (37/139 [27%]), ESUS (34/139 [24%]) and lastly TSS (20/139 [14%]). Patients with TSS were significantly younger (median age 60 years, range 50–66 years, p = 0.003) than other etiological subgroups.

Amid patient comorbidities, prior cerebrovascular events were most prevalent in CES (29%, 14/48) versus (9%, 3/34; p = 0.03) in ESUS group, yet was comparable to ICAS group (16%, 6/37; p = 0.20) and TSS (5%, 1/20; p = 0.05) (overall p = <0.001). Similarly, patients in the CES group demonstrated a greater proportion of hypercholesterolemia (17/48 [35%] vs. 3/34 [9%]; p = 0.008) relative to ESUS group and higher proportions (28/48 [58%]) of prior anti-thrombotic medications intake than ICAS (9/37 [24%]; p = 0.002) and ESUS (9/34 [26%]; p = 0.007) etiological subtypes. Atrial fibrillation was considered the underlying pathological mechanism of stroke in 54% of CES patients (n = 26), either alone or in combination with other cerebrovascular risk factors. Table 1 illustrates the demographics and clinical radiological characteristics of the patients.

The location of the occlusion at the initial cerebral angiography was different among the etiological subtypes (p = <0.001). Occlusion of distal BA was more frequent in the CES group (31/48; 65%) compared to ICAS (4/37 [11%]; p < 0.001) and ESUS (12/34 [35%]; p = 0.01) groups. On the contrary, the intracranial vertebral artery occlusion was more frequent in the ICAS group (9/37 [24%] vs. 2/48 [4%]; p = 0.009) compared to the CES group.

Predictors of Incomplete Reperfusion

Overall, successful reperfusion (mTICI 2b or 3) was noted in 79% (110/139) of the patients, which were inconstant among the groups (p = 0.009). The highest proportion was noted in the CES (94%, 45/48), whereas the lowest was discerned in the ESUS (65%, 22/34). On the other hand, complete reperfusion (mTICI 2c or 3) was achieved in 59% (82/139) of the patients with no depicted difference among the groups (p = 0.30). Procedures with incomplete reperfusion took a significantly longer time (aOR 1.018 [95% CI: 1.008–1.028]; p < 0.001). On the stepwise logistic regression analysis, incomplete reperfusion was negatively associated with the employment of the combined aspiration-retriever as the frontline thrombectomy strategy (aOR 0.188 [95% CI: 0.067–0.527]; p = 0.002) when adjusting for posterior communicating artery status (aOR 1.255 [95% CI: 0.955–1.648]; p = 0.10), and onset to puncture time interval (aOR 1.0014 [95% CI: 1.000–1.003]; p = 0.06) (Tables 2 and 3).

Procedural Technical Details

Despite comparable time interval from the stroke onset till groin puncture; however, the median number of passes was not significantly higher in the ICAS group compared to embolic groups (CES, ESUS), which might be concordant with the longer median procedural time in minutes (70 [52–107]) vs. (32 [20–59]; p = 0.001) vs. (47 [24–78]; p = 0.03), respectively. Contact aspiration (CA) was the most commonly employed reperfusion strategy (38% [53/139]). Refractory thrombectomy necessitated adjuvant maneuvers in 27% (n = 37) of the patients. Rescue angioplasty was performed in 15 patients (8 ICAS, 6 TSS, 1 ESUS), while adjuvant stenting was realized in 22 patients (15 intracranial stents in the ICAS group, 6 extracranial vertebral stents in the TSS group, and one in the ESUS group).

Predictors of 3-month Poor Functional Outcome

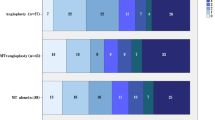

Of the patients 35% (49/139) achieved a good outcome. Fig. 2 illustrates the overall distribution of functional outcomes. The stepwise logistic regression analysis showed that ESUS was the most significant independent predictor (aOR 5.315 [95% CI: 1.646–17.163]; p = 0.005) of the poor outcome (Table 4) followed by Incomplete reperfusion (mTICI 0–2b) (aOR 3.007 [95% CI: 1.299–6.963]; p = 0.01) and onset to puncture interval (aOR 1.002 [95% CI: 1.0003–1.0036]; p = 0.02) and PC-ASPECTs (aOR 0.772 [95% CI: 0.617–0.965]; p = 0.02) when adjusting for administration of intravenous tPA (aOR 0.5283 [95% CI: 0.2312–1.2073]; p = 0.13).

Graph demonstrates the distribution of functional outcome at 90 days (measured by modified Rankin scale score) following endovascular thrombectomy in various etiological subtypes of vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke as verified by baseline angiography and functional cardiovascular assessment. Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) showed the highest proportion of the poor outcome (mRS 3–6) compared to other etiopathological mechanisms of stroke. CES cardioembolic stroke, ESUS embolic stroke of undetermined source, ICAS intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis, TSS tandem steno-occlusive stroke

Post-EVT Short-term Complications and Mortality

Out of 139 patients 7 (5%) had a symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage. The 90-day mortality was 40% (55/139) which was significantly associated with the periprocedural sICH (aOR 20.778 [95% CI: 2.179–198.157]; p < 0.001), intracranial vertebral occlusion site (aOR 6.098 [95% CI: 1.702–21.842]; p = 0.006), ESUS (aOR 4.667; [95% CI: 1.883–11.564]; p < 0.001), and incomplete reperfusion (mTICI 0–2b) (aOR 3.392 [95% CI: 1.505–7.642]; p = 0.008) after adjustment for the intravenous rtPA, distal BA occlusion site, baseline PC-ASPECTs, puncture to reperfusion interval, CES in the stepwise logistic regression model (Table 5, supplemental table I).

Discussion

The present study showed that the ESUS, distinctly from other etiopathological mechanisms of stroke, was independently associated with poor functional outcomes (aOR 5.315 [95% CI: 1.646–17.163]; p = 0.005) and 90-day mortality (aOR 4.667; [95% CI: 1.883–11.564]; p = < 0.001) following EVT in patients with VBOS.

The CES, which showed a predilection for distal BA involvement, was associated with shorter procedural times (32 vs. 70 vs. 72 vs. 47 min; p < 0.001), higher rates of successful reperfusion (94% vs. 78% vs. 70% vs. 65%; p = 0.009) compared to the ICAS, TSS and ESUS groups respectively; however, this was not reflected in the functional outcomes. Conversely, the LAA, which exhibited a greater tendency for proximal vertebrobasilar involvement; necessitated a greater proportion of rescue maneuvers (61%, 35/57; p < 0.001), which was concordant with a longer puncture to reperfusion interval (70 min), and significantly lower rates of successful reperfusion (75%, 43/57 vs. 94%, 45/48); yet, with comparable proportions of poor outcome (60%, 34/57 vs. 54%, 26/48) relevant to the CES. No significant differences in the rate of periprocedural sICH were observed among the groups. Incomplete reperfusion was an independent predictor (aOR, 3.007 [95% CI: 1.299–6.963]; p = 0.01) of poor functional outcome and 90-day mortality (aOR 3.392 [95% CI: 1.505–7.642]; p = 0.008).

Etiological Classification of Stroke

Baik et al. [9] classified the stroke etiology into ICAS-related thrombotic stroke, tandem steno-occlusive, and embolic strokes on an angiographic basis, and complimentary standard cardiac work-up; however, nearly one quarter of the extracranial tandem and intracranial atherosclerotic groups had atrial fibrillation, which might provoke mislabeling that could corrupt correlation to angiographic and functional outcomes, peculiarly in a relatively small sample size. More recently, Sun et al. [10] identified three analogous angiographic subtypes irrespective of the clinical context. The exclusive use of angiography for characterizing the cause of the stroke might be valuable in field-based therapeutic decision-making; however, clinical reciprocity would be advantageous to outline the grand patient-tailored management plan.

The National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Blindness (NINDB) described the leading etiological classification of ischemic stroke in 1958. Four groups were detailed: thrombosis with atherosclerosis, cerebral embolism, other causes, and cerebral infarction of undetermined origin. The latest advancements in medical imaging technology by the inauguration of high-field MRI scanners in congruence with echocardiographic evolution prompted the implementation of the TOAST in clinical practice and epidemiological studies [11].

The TOAST classification, the most widely used classification system nowadays [13], showed many critics attributed to the moderate interrater agreement. Nonetheless, algorithmic complexity and the web-based necessity of modern classification systems emphasized further the simplicity and the applicability of the original TOAST. On that account, etiological classification in our study was performed following the TOAST criteria. We identified three major groups: LAA (41%, which was further subcategorized into ICAS 27%, and TSS 14%), CES (35%), and ESUS (24%) that were comparable with the results of a recent angiography-based report [10].

Intracranial Atherosclerotic Stenosis (ICAS)

Functional outcomes of patients with ICAS-BAO who underwent thrombectomy are not congruous throughout the literature. Previous monocentric studies and a recent meta-analysis reported a non-significant difference in the rates of 90-day functional independence (37% vs. 41%; p = 0.22), sICH (5% vs. 6%; p = 0.57), or mortality (22% vs. 24%; p = 0.14) after EVT, between patients with and without underlying ICAS [14,15,16,17,18]. On the contrary, Nardai et al. reported higher overall mortality, which might be attributable to longer onset reperfusion times and lower rates of successful reperfusion in the ICAS group [19]. Similarly, Kim et al. showed that patients with ICAS had lower rates of a good outcome, despite similar reperfusion rates. Therefore, the functional outcome might not depend solely on the successful reperfusion but on other determinants such as the initial severity of neurologic deficits, onset to reperfusion times, clot location, grading of collaterals, and the endovascular strategy [20, 21]. In the current study, we found no significant differences concerning the angiographic and functional outcome between ICAS and CES groups; however, the ICAS group showed higher mortality rates, which might be associated with the clot location and procedural times. The latter, a significant predictor of the mortality rate, was longer in the ICAS group (72 versus 30 min; p < 0.001), which is perspicuous owing to the reocclusive behavior which necessitated frequent thrombectomy attempts and adjuvant rescue treatment [22, 23].

Tandem Steno-occlusion Stroke (TSS)

Although reperfusion is still considered the most cardinal predictor of a good outcome in BAO, there is considerable heterogeneity concerning the functional outcome at comparable reperfusion grades [24,25,26]. Mahmoud et al. found no statistically significant difference between patients with TSS and non-TSS with respect to the rates of successful reperfusion, functional independence, or mortality rate [22]. Jiang et al. stated that patients with TSS achieved the most favorable outcomes compared to other etiological subtypes despite a similar reperfusion rate, which could result from better collateral circulation [23]. Elhorany et al. declared a less favorable outcome and higher mortality rates concomitant with lower rates of successful reperfusion in those with TSS [27]. Other studies emphasized that TSS might be associated with lower rates of good outcomes (between 26.6–53.3%) and higher mortality (20–42.9%) despite successful reperfusion (ultimately up to 100%), which might be attributable to lengthy procedural times and persistent occlusion of basilar perforators [28]. Patients with TSS in the current study showed functional independence in 45% and mortality in 40%, which are comparable to the previous studies.

The TSS revascularization might be associated with higher rates of downstream embolization subsequent to repeated employment of rescue maneuvers. Moreover, TSS revascularization might be a technically complex and lengthy procedure as a result of potential atherosclerotic tortuous vasculature, frequent attempts to engage the ostium of the steno-occluded VA, and difficulties bypassing distal steno-occluded VA segments, which might explain relatively higher mortality rates in the current study.

Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (ESUS)

In a case-control study conducted by Karttunen et al., hypertension, current smoking, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and high clotting factor VIII activity were more prevalent in the ESUS with disproportionate distribution between men and women [29]. Contrastingly in a population-based study of 2555 patients, the ESUS group predicated on TOAST criteria presented with fewer atherosclerotic risk factors with no surplus risk of asymptomatic carotid stenosis or acute coronary events during the follow-up in opposition to LAA and CES groups [30]. Conforming to the latter, patients with ESUS in our study showed lower proportions of hypercholesterolemia and cerebrovascular events relative to the CES. Based on TOAST criteria in the Get with the Guidelines (GWTG) stroke registry [31], ESUS patients with a lower admission NIHSS were more likely to be discharged home independently compared to all other etiologies adding to lower mortality rates in contrast to LAA and CES groups. Incongruously, Li et al. [26] declared a similar 6‑month death or dependency rate between ESUS and non-CES. In an earlier study [32], the thrombi of ESUS etiology showed a significant overlap with the CES, exhibiting higher proportions of fibrin/platelets, leucocytes, and lower erythrocytes relative to the non-CES. Furthermore, patients with ESUS had higher initial NIHSS and post-thrombectomy worse functional outcomes in line with a higher number of maneuvers compared to the non-CES. The outcome divergence might correlate with different etiological classifications and the variable definition of the ESUS in the literature, which relies principally on the degree of testing performed, whether standard or advanced/specialized, and the post-thrombectomy period of follow-up. In the present study, the work-up investigations were consistent for all patients; however, considering relatively higher proportions of early mortality (88% vs. 57%; p < 0.001) in the ESUS group concordant with the reduced median length of hospitalization days (6 [3–9.5] vs. 16 [7–27]; p < 0.001), higher proportions in the ESUS group underwent only transthoracic echocardiography with its known limitation in comparison to the rest of the cohort. ESUS in our study was the most significant predictor of the poor functional outcome with a relatively higher mortality rate despite a more favorable comorbidities profile. Despite higher rates of failed reperfusion in the ESUS, it might not explain the differences in outcome since functional dependence was principally associated with incomplete rather than failed reperfusion. On that account, variable clot location, which was significantly associated with 90-day mortality (p = 0.02), might elucidate the higher mortality rates. Analogous to the ICAS, ESUS was relatively more frequent in the intracranial VA (18% vs. 4%, p = 0.03) in contrast to the CES, which preferentially tends to involve distal BA (65% vs. 35%, p = .01). Following prior studies, occlusion of proximal and middle segments of the basilar artery, which supply most of the pons, could lead to extensive grave pontine ischemia, which is conceptually worse than distal occlusions [33, 14]. Considering that we included only patients with lone V4 segment occlusion and aplastic or non-contributive contralateral VA, vertebral occlusion might leave a comparable ischemic burden to proximal-middle basilar occlusion.

Our study has potential limitations: although consecutive VBOS patients were enrolled, our study design was retrospective and non-controlled. Also to be acknowledged, the existence of too many significant variables relative to the sample volume after the univariate analysis; prompted the employment of stepwise logistic regression analysis with its known limitations. Despite known superiority in left atrial abnormalities, transthoracic echography compulsorily substituted transesophageal echography in patients with dysphagia or very poor clinical condition; thence, overinflation of ESUS was unavoidable. There is still a probability that ESUS patients might achieve worse clinical outcomes due to less diagnostic follow-up in heavily affected patients; however, ESUS patients maintained the significant association with the worse functional outcome (mRS 3–4) (Supplemental tables II, III) after exclusion of heavily affected (mRS 5) and deceased patients (mRS 6), who would be more probably affected with the duration of the follow-up.

Moreover, no specialized biomarkers or histological analyses were performed for the retrieved thrombi to verify the etiological diagnosis. Furthermore, we included only patients who underwent MRI before thrombectomy to homogenize the studied cohort. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings should be performed with caution. Finally, our study was underpowered to designate the proper EVT technique that would effectuate complete reperfusion in the context of etiology. Nonetheless, we did not find any difference among our groups in terms of complete reperfusion rate, which independently impacts the functional outcome. Further multicenter studies might be warranted to confirm our results and characterize the predictors of the functional outcome in a larger cohort.

Conclusion

Vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke (VBOS) is innately associated with higher morbimortality. Nonetheless, while exalting intracranial atherosclerosis and tandem-related steno-occlusive stroke as prognostic predictors of functional outcome, abiding skepticism remains regarding the prognosis of the embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) entity. ESUS was associated with the worst functional outcome in contrast to other etiological subtypes, despite analogous complete reperfusion rates. Future prospective multicenter studies are necessary to confirm our findings.

Abbreviations

- BA:

-

Basilar artery

- BAO:

-

Basilar artery occlusion

- CES:

-

Cardioembolic stroke

- ESUS:

-

Embolic stroke of undetermined source

- EVT:

-

Endovascular thrombectomy

- IA-GPI:

-

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

- intra-arterial ICAS:

-

Intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis

- LAA:

-

Large artery atherosclerosis

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin scale

- mTICI:

-

Modified treatment in cerebral infarction

- NIHSS:

-

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- PC-ASPECTs:

-

Posterior circulation-Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score

- sICH:

-

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage

- TOAST:

-

Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment

- tPA:

-

Tissue plasminogen activator

- TSS:

-

Tandem steno-occlusion stroke

- VA:

-

Vertebral artery

- VBOS:

-

Vertebrobasilar occlusion stroke

References

Liu X, Dai Q, Ye R, Zi W, Liu Y, Wang H, Zhu W, Ma M, Yin Q, Li M, Fan X, Sun W, Han Y, Lv Q, Liu R, Yang D, Shi Z, Zheng D, Deng X, Wan Y, Wang Z, Geng Y, Chen X, Zhou Z, Liao G, Jin P, Liu Y, Liu X, Zhang M, Zhou F, Shi H, Zhang Y, Guo F, Yin C, Niu G, Zhang M, Cai X, Zhu Q, Chen Z, Liang Y, Li B, Lin M, Wang W, Xu H, Fu X, Liu W, Tian X, Gong Z, Shi H, Wang C, Lv P, Tao Z, Zhu L, Yang S, Hu W, Jiang P, Liebeskind DS, Pereira VM, Leung T, Yan B, Davis S, Xu G, Nogueira RG; BEST Trial Investigators. Endovascular treatment versus standard medical treatment for vertebrobasilar artery occlusion (BEST): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:115–22.

Writing Group for the BASILAR Group, Zi W, Qiu Z, Wu D, Li F, Liu H, Liu W, Huang W, Shi Z, Bai Y, Liu Z, Wang L, Yang S, Pu J, Wen C, Wang S, Zhu Q, Chen W, Yin C, Lin M, Qi L, Zhong Y, Wang Z, Wu W, Chen H, Yao X, Xiong F, Zeng G, Zhou Z, Wu Z, Wan Y, Peng H, Li B, Hu X, Wen H, Zhong W, Wang L, Jin P, Guo F, Han J, Fu X, Ai Z, Tian X, Feng X, Sun B, Huang Z, Li W, Zhou P, Tu M, Sun X, Li H, He W, Qiu T, Yuan Z, Yue C, Yang J, Luo W, Gong Z, Shuai J, Nogueira RG, Yang Q. Assessment of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion via a Nationwide Prospective Registry. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:561–73.

Xun K, Mo J, Ruan S, Dai J, Zhang W, Lv Y, Du N, Chen S, Shen Z, Wu Y. A Meta-Analysis of Prognostic Factors in Patients with Posterior Circulation Stroke after Mechanical Thrombectomy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;50:185–99.

Mahmoudi M, Dargazanli C, Cagnazzo F, Derraz I, Arquizan C, Wacogne A, Labreuche J, Bonafe A, Sablot D, Lefevre PH, Gascou G, Gaillard N, Scott C, Costalat V, Mourand I. Predictors of Favorable Outcome after Endovascular Thrombectomy in MRI: Selected Patients with Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1670–6.

Abdelrady M, Ognard J, Cagnazzo F, Derraz I, Lefevre PH, Riquelme C, Gascou G, Arquizan C, Dargazanli C, Cheddad El Aouni M, Ben Salem D, Mourand I, Costalat V, Gentric JC; RAMBO (Revascularization via Aspiration or Mechanical thrombectomy in Basilar Occlusion). Frontline thrombectomy strategy and outcome in acute basilar artery occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2021-018180.

Guillaume M, Lapergue B, Gory B, Labreuche J, Consoli A, Mione G, Humbertjean L, Lacour JC, Mazighi M, Piotin M, Blanc R, Richard S; Endovascular Treatment in Ischemic Stroke (ETIS) Investigators. Rapid Successful Reperfusion of Basilar Artery Occlusion Strokes With Pretreatment Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Posterior-Circulation ASPECTS <8 Is Associated With Good Outcome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010962.

Goyal N, Tsivgoulis G, Nickele C, Doss VT, Hoit D, Alexandrov AV, Arthur A, Elijovich L. Posterior circulation CT angiography collaterals predict outcome of endovascular acute ischemic stroke therapy for basilar artery occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:783–6.

Maus V, Kalkan A, Kabbasch C, Abdullayev N, Stetefeld H, Barnikol UB, Liebig T, Dohmen C, Fink GR, Borggrefe J, Mpotsaris A. Mechanical Thrombectomy in Basilar Artery Occlusion : Presence of Bilateral Posterior Communicating Arteries is a Predictor of Favorable Clinical Outcome. Clin Neuroradiol. 2019;29:153–60.

Baik SH, Park HJ, Kim JH, Jang CK, Kim BM, Kim DJ. Mechanical Thrombectomy in Subtypes of Basilar Artery Occlusion: Relationship to Recanalization Rate and Clinical Outcome. Radiology. 2019;291:730–7.

Sun X, Raynald, Tong X, Gao F, Deng Y, Ma G, Ma N, Mo D, Song L, Liu L, Huo X, Miao Z. Analysis of Treatment Outcome After Endovascular Treatment in Different Pathological Subtypes of Basilar Artery Occlusion: a Single Center Experience. Transl Stroke Res. 2021;12:230–8.

Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE 3rd. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41.

Neuberger U, Möhlenbruch MA, Herweh C, Ulfert C, Bendszus M, Pfaff J. Classification of Bleeding Events: Comparison of ECASS III (European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study) and the New Heidelberg Bleeding Classification. Stroke. 2017;48:1983–5.

Radu RA, Terecoasă EO, Băjenaru OA, Tiu C. Etiologic classification of ischemic stroke: Where do we stand? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;159:93–106.

Wu L, Rajah GB, Cosky EE, Wu X, Li C, Chen J, Zhao W, Wu D, Ding Y, Ji X. Outcomes in Endovascular Therapy for Basilar Artery Occlusion: Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease vs. Embolism. Aging Dis. 2021;12:404–14.

Lee YY, Yoon W, Kim SK, Baek BH, Kim GS, Kim JT, Park MS. Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion: Differences in Characteristics and Outcomes after Endovascular Therapy between Patients with and without Underlying Severe Atherosclerotic Stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:1600–4.

Lin YH, Chen KW, Tang SC, Lee CW. Endovascular Treatment Outcome and CT Angiography Findings in Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion with and without Underlying Intracranial Atherosclerotic Stenosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:747–53.

Baek JH, Kim BM, Heo JH, Kim DJ, Nam HS, Kim YD. Endovascular and Clinical Outcomes of Vertebrobasilar Intracranial Atherosclerosis-Related Large Vessel Occlusion. Front Neurol. 2019;10:215.

Bao J, Hong Y, Cui C, Ma M, Gao L, Liu Q, Chen N, He L. Efficacy and safety of endovascular treatment for patients with acute intracranial atherosclerosis-related posterior circulation stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Neurosci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2020-0025.

Baek JH, Kim BM. Angiographical Identification of Intracranial, Atherosclerosis-Related, Large Vessel Occlusion in Endovascular Treatment. Front Neurol. 2019;10:298.

Kim YW, Hong JM, Park DG, Choi JW, Kang DH, Kim YS, Zaidat OO, Demchuk AM, Hwang YH, Lee JS. Effect of Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease on Endovascular Treatment for Patients with Acute Vertebrobasilar Occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:2072–8.

Siebert E, Bohner G, Zweynert S, Maus V, Mpotsaris A, Liebig T, Kabbasch C. Revascularization Techniques for Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion : Technical Considerations and Outcome in the Setting of Severe Posterior Circulation Steno-Occlusive Disease. Clin Neuroradiol. 2019;29:435–43.

Mahmoud MN, Zaitoun MMA, Abdalla MA. Revascularization of vertebrobasilar tandem occlusions: a meta-analysis. Neuroradiology. 2022;64:637–45.

Jiang L, Yang JH, Ruan J, Xia WQ, Huang H, Zhang H, Chen TW, Li LF, Yin CG. A Single-Center Experience of Endovascular Treatment in Subtypes of Basilar Artery Occlusion: Embolization Caused by Tandem Vertebral Artery Stenosis May Be Associated with Better Outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2021;151:e918–26.

Chang JY, Jung S, Jung C, Bae HJ, Kwon O, Han MK. Dominant vertebral artery status and functional outcome after endovascular therapy of symptomatic basilar artery occlusion. J Neuroradiol. 2017;44:151–7.

Deb-Chatterji M, Flottmann F, Leischner H, Alegiani A, Brekenfeld C, Fiehler J, Gerloff C, Thomalla G. Recanalization is the Key for Better Outcome of Thrombectomy in Basilar Artery Occlusion. Clin Neuroradiol. 2020;30:769–75.

Weyland CS, Neuberger U, Potreck A, Pfaff JAR, Nagel S, Schönenberger S, Bendszus M, Möhlenbruch MA. Reasons for Failed Mechanical Thrombectomy in Posterior Circulation Ischemic Stroke Patients. Clin Neuroradiol. 2021;31:745–52.

Elhorany M, Boulouis G, Hassen WB, Crozier S, Shotar E, Sourour NA, Lenck S, Premat K, Fahed R, Degos V, Elhfnawy AM, Mansour OY, Tag El-Din EA, Fadel WA, Alamowitch S, Samson Y, Naggara O, Clarençon F. Outcome and recanalization rate of tandem basilar artery occlusion treated by mechanical thrombectomy. J Neuroradiol. 2020;47:404–9.

Weinberg JH, Sweid A, Sajja K, Abbas R, Asada A, Kozak O, Mackenzie L, Choe H, Gooch MR, Herial N, Tjoumakaris S, Zarzour H, Rosenwasser RH, Jabbour P. Posterior circulation tandem occlusions: Classification and techniques. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;198:106154.

Karttunen V, Alfthan G, Hiltunen L, Rasi V, Kervinen K, Kesäniemi YA, Hillbom M. Risk factors for cryptogenic ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:625–32.

Li L, Yiin GS, Geraghty OC, Schulz UG, Kuker W, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM; Oxford Vascular Study. Incidence, outcome, risk factors, and long-term prognosis of cryptogenic transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:903–13.

Prabhakaran S, Messé SR, Kleindorfer D, Smith EE, Fonarow GC, Xu H, Zhao X, Lytle B, Cigarroa J, Schwamm LH. Cryptogenic stroke: Contemporary trends, treatments, and outcomes in the United States. Neurol Clin Pract. 2020;10:396–405.

Boeckh-Behrens T, Kleine JF, Zimmer C, Neff F, Scheipl F, Pelisek J, Schirmer L, Nguyen K, Karatas D, Poppert H. Thrombus Histology Suggests Cardioembolic Cause in Cryptogenic Stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:1864–71.

Zhang X, Luo G, Jia B, Mo D, Ma N, Gao F, Zhang J, Miao Z. Differences in characteristics and outcomes after endovascular therapy: A single-center analysis of patients with vertebrobasilar occlusion due to underlying intracranial atherosclerosis disease and embolism. Interv Neuroradiol. 2019;25:254–60.

Members of RAMBO*(Reperfusion via Aspiration or Mechanical thrombectomy in Basilar Occlusion)-investigators group

Mohamed Abdelrady, Imad Derraz, Pierre-Henri Lefevre, Federico Cagnazzo, Carlos Riquelme, Gregory Gascou, Lucas Corti, Nicolas Gaillard, Mourad Cheddad El Aouni, Douraied Ben Salem, Cyril Dargazanli, Julien Ognard, Isabelle Mourand, Caroline Abdelrady, Jean-Christophe Gentric, Vincent Costalat.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Study design: Mohamed Abdelrady, Imad Derraz, Julien Ognard. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Mohamed Abdelrady and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Statistical analysis: Mohamed Abdelrady, Julien Ognard. Supervision: Vincent Costalat, Jean Christophe Gentric, Isabelle Mourand, Caroline Arquizan. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M. Abdelrady, I. Derraz, C. Dargazanli, F. Cagnazzo, J. Ognard, C. Riquelme, M. Cheddad El Aouni, P.-H. Lefevremd, D. Ben Salem, G. Gascou, J.-C. Gentric, C. Arquizan, V. Costalat, and I. Mourand declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case. Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of University hospitals of Montpellier and Brest in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care. This retrospective study was performed after consultation with the institutional ethics committee and in accordance with national legal requirements.

Additional information

Data availability

Anonymized individual participant data will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request from any qualified investigator for 12 months after the date of publication.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelrady, M., Derraz, I., Dargazanli, C. et al. Outcomes Following Mechanical Thrombectomy in Different Etiological Subtypes of Acute Basilar Artery Occlusion. Clin Neuroradiol 33, 361–374 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-022-01217-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-022-01217-3