Abstract

Whether the caste fate of social insects is determined before or after emergence is a key question for understanding the evolution of eusociality. Paper wasps are a suitable model for answering this question because there are no critical morphological differences between queens and workers in paper wasps, and these animals appear to represent an early stage of eusociality. We explored the above question by determining the effects of photoperiod during the adult stage on caste-fate determination in the paper wasp Polistes jokahamae. We collected colonies at different stages in the field and exposed emerging adults individually to long or short days. Under these isolated conditions, gyne-destined (diapausing) females were expected to exhibit large lipid stores without mature eggs, while the reverse was expected to be true for worker-destined (nondiapausing) females. The proportion of wasps with mature eggs was higher under long days in the second and subsequent broods, but not in the first brood. Lipid stores were larger among large females and under short days, and smaller for the first brood. These findings together suggest that the first brood emerges with a strong preimaginal bias toward workers (nondiapausing form), whereas the other broods emerge with no bias or an easily reversible bias. However, it is difficult to conclude whether the bias came from body size or the season of emergence. We discuss the possibility that the ancestor of paper wasps had workers with and without preimaginal bias toward becoming workers at emergence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The origin of eusociality, in which a colony includes nonreproductive individuals (usually referred to as workers), has attracted the interest of both evolutionary biologists (Futuyma and Kirkpatrick 2017) and sociobiologists (Wilson 1975). A presumably fruitful approach for understanding the origin of workers is to elucidate the mechanisms underlying caste-fate determination in primitively eusocial species (Oster and Wilson 1978; Hunt 1991; Smith et al. 2008) in which there are no critical morphological differences between the queen and workers (Michener 1964; Wilson 1971; Jeanne 2003) because primitive eusociality appears to represent an early stage of eusociality (Wilson 1971; Wheeler 1986; Hunt 2012; Boomsma and Gawne 2018; Piekarski et al. 2018). All individuals of these species have the capability of reproducing, and levels of sociality are less developed than in advanced eusocial organisms in terms of colony size and conflict and cooperation among the queen and workers. In particular, primitively eusocial groups in Polistinae are suitable models for exploring the evolution of eusociality because their sociality originated in the shared ancestor of the subfamilies Polistinae and Vespinae (Piekarski et al. 2018), which include advanced eusocial species as well as primitive eusocial species. Thus, studying primitive eusociality in paper wasps, such as Polistes, can provide insight into some of the possible traits involved in caste determination (Jandt and Toth 2015).

It has often been suggested that Vespidae evolved eusociality through the following steps (Pardi 1948; West-Eberhard 1978; Carpenter 1991; Gadagkar 1991; Field and Foster 1999; Noll et al. 2004; Hunt 2012; Piekarski et al. 2018): (1) solitary habits, (2) casteless nest sharing, (3) eusociality with behavioral castes that do not include preimaginal caste-related biasing (PCB), (4) eusociality with PCB, and (5) eusociality with morphologically differentiated castes. The development of sociality might originate from the first brood comprising nondiapausing adults in temperate groups (diapause ground-plan hypothesis; Hunt and Amdam 2005; Hunt 2006, 2007, 2012). However, this assumption is challenged by the following two facts, as suggested by Kelstrup et al. (2017): (1) the phylogenic and biogeographical analysis of Santos et al. (2015) in Polistes paper wasps suggested that the genus originated in a tropical area, and (2) very few temperate solitary wasps overwinter as adults (Evans and West-Eberhard 1970). Furthermore, Piekarski et al. (2018) recently performed a phylogenomic analysis to explore the relationships between vespid species and consequently proposed the hypothesis that eusociality in Polistinae and Vespinae arose abruptly in a shared ancestor of the two subfamilies with morphological PCB (including size differences) as well as physiological PCB. They suggested that the abrupt appearance of eusociality could have arisen from daughter subfertility (West-Eberhard 1975; Craig 1983; first-brood daughters are likely to be malnourished because only the mother nurses the offspring) in colonies composed of a mother and daughters. The hypothesis of abrupt appearance of castes with morphophysiological differences is fascinating and somewhat surprising to researchers of social hymenopterans. One way to better address this hypothesis is to determine caste-fate determination mechanisms using a range of different species of vespid wasps with varying levels of sociality; in particular, this strategy can elucidate how and when PCB occurred and was made stronger during the evolution of eusociality in vespid wasps.

Temperate paper wasps are suitable animals for exploring the origin of workers because the castes, particularly gynes (foundress-queen candidates of the next spring), are distinguishable by physiological traits related to diapause even though they do not have morphological differences. The females that prepare for overwintering, i.e. store lipids, are classified as diapausing females (i.e. gynes) (Eickwort 1969; Strassmann et al. 1984; Toth et al. 2009; Yoshimura and Yamada 2018a), while those that do not are classified as nondiapausing females, including workers, replacement queens, and mid-season foundresses (Strassmann 1981; Page et al. 1989). Moreover, gynes do not develop mature ovaries before overwintering, while nondiapausing females do so before overwintering to perform oviposition under certain conditions (Haggard and Gamboa 1980; Toth et al. 2009), such as when they are dominant or leave their natal nests. First-brood females of some species mate with early males and found new colonies without overwintering (Strassmann 1981; Page et al. 1989; see also Liebert et al. 2004). Some first-brood females of P. jokahamae may become mid-season founders due to nest collapse or replacement queens due to the disappearance of the foundress queens; the former case is rare according to our observation. However, these females are considered to lay only male eggs because very few males are found in the first brood and the females have no chance to mate (see Miyano 1991; Yoshimura et al. 2019); that is, they cannot become true queens and are often classified into the worker caste (O’Donnell 1998). Hence, whether a P. jokahamae individual enters diapause is strongly linked to whether the individual becomes a queen.

Most researchers consider the caste fate of temperate paper wasps to be finally determined by cues received after emergence, even though PCB may occur during the immature stage (Berens et al. 2015; Judd et al. 2015; Judd 2018; Yoshimura and Yamada 2018b). Such PCB is induced by the nutritional level, vibration, and photoperiod (O’Donnell 1998; Hunt 2006; Hunt et al. 2007; Jeanne and Suryanarayanan 2011; Jandt et al. 2017; Yoshimura and Yamada 2018b). The determinants of caste after emergence include the presence of the queen and broods and the photoperiod (Bohm 1972; Solís and Strassmann 1990; Reeve et al. 1998; Tibbetts 2007; Judd 2018; Yoshimura and Yamada 2018b).

Regarding the effects of photoperiod on caste-fate determination, Bohm (1972) revealed the existence of PCB (i.e. preimaginal diapause-related bias) by exposing females of the paper wasp Polistes metricus from different broods to short or long days. The first brood had no PCB, while the other broods exhibited PCB toward gynes. Our previous study (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018b) revealed that the photoperiod during the adult stage is a cue for caste-fate determination in Polistes jokahamae: when females experience long and short days during the adult stage, they exhibit the physiological traits of nondiapausing and diapausing forms, respectively. However, there were no differences in the effect of photoperiod between different-brood females, probably because the colonies in that study were collected before the emergence of the first brood, placed under constant temperatures and a controlled photoperiod, and supplied with enough food. In contrast, the first-brood P. jokahamae adults emerging from nests collected in the field emerge with a bias toward workers: they are small and thin and emerge with lower lipid stores (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018a). Thus, when P. jokahamae females are exposed to similar experimental procedures to those of Bohm (1972), they may exhibit PCB; in particular, the first brood may do so toward workers, that is, individuals with nondiapausing physiological characteristics (Table 1).

Here, we aimed to elucidate the existence of PCB (i.e. preimaginal diapause-related bias) through the examination of the effects of photoperiod during the adult stage on caste-fate determination using females from different broods of P. jokahamae. When all adults of a brood exhibited mature eggs and low lipid stores under both short and long days, the brood was assumed to exhibit a strong preimaginal bias toward the nondiapausing form, which usually becomes a worker (Table 1). In contrast, when all adults of a brood refrained from develop ovaries and had large lipid stores under both short and long days, the brood was assumed to present a strong preimaginal bias toward the diapausing form (gynes). When all females exhibited egg maturation and low lipid stores under long days and all females refrained from developing ovaries and had large lipid stores under short days, the brood was assumed to exhibit no PCB or quite weak PCB (Table 1). In addition, we analyzed the effects of the body size of adults on caste-fate determination because smaller females were less likely to prepare for diapause in our previous experiments (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018a, b).

Materials and methods

Study species

Polistes jokahamae is distributed throughout Japan except for in Hokkaido and is particularly common in the southern area of Japan. Foundresses start to solitarily found nests around late April in Mie, Japan, after they have overwintered. Daughters start to emerge from late May to mid-June and usually continue to emerge until mid- to late August (Yoshimura et al. 2019). Males emerge mainly in August. Gynes mate from late October to early November and then enter diapause.

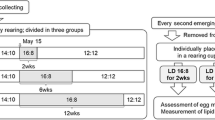

Collection of colonies and categorization of broods

A total of 38 colonies with pupae were collected from May 23 to August 18, 2016, and from May 22 to August 21, 2017, in Tsu, Mie, Japan (Table 2). The collected nests were kept at 25 °C under photoperiod conditions simulating changes in the natural day length, which was defined as 1 h longer than the period from sunrise to sunset. Adults emerging from cocoons that were present when the nests were collected were used for the experiments, providing a total of 191 females for the analysis (Table 2).

The females in the nests were divided into the first, second, and third broods. The first brood was nursed only by the foundress. The second brood was nursed by the foundress queen and first-brood females and emerged before male emergence. The third brood was also nursed by the foundress and workers but emerged at the same time as or later than the males. The first brood emerged from late May to mid-June, the second brood emerged from mid-June to July, and the third brood emerged mainly in August.

Treatments

Newly emerged females were removed from the natal nests immediately after emergence and placed individually in transparent plastic cups (12 cm diameter × 6 cm deep) for 2 weeks under a 16:8 h LD or a 12:12 h LD at 25 °C, representing day lengths similar to those at the time of the summer solstice (1.5 h longer than the period from sunrise to sunset) and in mid-October (1 h longer than the period from sunrise to sunset), respectively. One third-to-fifth-instar silk moth (Bombyx mori) larva was placed in each rearing cup with water and honey. On emergence days (before food and water were supplied), the head width of the adult wasps was measured using calipers with a precision of 0.01 mm. The water and honey were renewed once per week, and the moth larva was replaced when it was injured.

After being reared for 2 weeks, the wasps were dissected under a microscope to examine whether they exhibited mature eggs. In addition, the lipid stores in the gaster were estimated by measuring the difference in dry mass before and after lipid extraction using diethyl ether as described by Tibbetts et al. (2011). The dry mass was measured using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.0001 g.

Data analysis

First, we compared the body size (head width) of the wasps between the two investigation years and between different broods. The analysis was performed using a mixed GLM (General Linear Model) implemented in NCSS (version 11, NCSS Statistical Software, Kaysville, UT, USA). The colony was incorporated in the models as a random factor. The results showed that adult size differed among different broods and between the two years, indicating multicollinearity among the three factors of brood, body size, and year. The values of the variance inflation factor (VIF), which is often used as a measure of the strength of multicollinearity, for each explanatory value were not high (1.08–1.86). However, if a given factor is related to another factor, the factor may be excluded from the minimally adequate model (Zuur et al. 2010), although it has a significant effect on the response variable. Thus, when performing the below analyses, the brood, body size, and year were incorporated separately in the statistical models to avoid multicollinearity. In addition, we compared the emergence day of the wasps in each brood between the two years to test whether a possible yearly difference in the emergence day caused the above yearly difference in the body size and/or a possible yearly difference in egg maturation and lipid stores.

The effects of the following four potential explanatory variables and the two-way interactions between them on egg maturation (proportion of wasps with mature eggs) were analyzed with logistic regression: (1) day length during the adult stage, (2) adult size (head width), (3) brood, and (4) year. Parameters other than adult size were included in the model as categorical variables. We performed a logistic mixed-model analysis using the “lme4” package in R software (version 3.4.3; R Foundation 2017). A logit link function was applied, and the colony was incorporated as a random factor, including a random slope against head width and a random intercept. The significance of each factor was determined by a likelihood ratio test for the models with and without a focal factor. Starting with the interactions in the full models including the day length, one of the parameters of adult size, brood, or year, and their two-way interactions, we tested the significance of each factor using backward stepwise regression analysis. The focal term was removed from the model when it was not significant. We report the P values for the individual terms: those for nonsignificant terms were obtained when the terms were removed, and those for significant terms were obtained when the terms were removed from the minimally adequate model. When a difference was detected between broods, a sequential Bonferroni multiple comparison test (Holm 1979; Rice 1989) was performed to identify the pairs exhibiting statistically significant differences using the “multcomp” package in R software.

The index of relative lipid stores (IRL), which was defined as (lipid stores)/(head width cubed) (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018a), was used in the analysis to control for body size. The factors influencing the IRL were analyzed with a mixed GLM incorporating the day length and one of the parameters of brood, body size, year, or egg maturation (absence or presence of mature eggs) as fixed factors using the “lme4” package in R software, as the factor of egg maturation was also related to the other three factors, causing multicollinearity (VIF = 1.28). The colony was incorporated as a random factor. A logarithmic transformation was applied to the response variable (IRL) to ensure that the random errors conformed to a normal distribution.

Furthermore, we analyzed the effects of the emergence days of individual wasps on egg maturation and lipid stores separately for each of the three broods. The photoperiod and emergence day were incorporated as fixed factors, and the colony was incorporated as a random factor.

Results

Body size and emergence day

Body size was significantly larger in 2016 than in 2017 (Table 3; F1, 33.6 = 4.6, P = 0.039) and differed significantly between broods (F2, 31.8 = 18.0, P < 0.001), with no significant interaction (F2, 29.4 = 0.3, P = 0.773). The body size of the second and third broods was larger than that of the first brood in 2016 (Table 3), but the difference was not significant in 2017: note that this yearly difference may be due to the low numbers of colonies collected in 2017 (Table 2). The emergence days did not differ between different years (F1, 13.9 = 0.1, P = 0.737 for first brood; F1, 16.9 = 0.6, P = 0.450 for second brood; F1, 1.9 = 8.5, P = 0.109 for third brood).

Egg maturation

The year and day length during the adult stage had independent effects on the proportion of females with mature eggs (\({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 24.5, P < 0.001 for day length; \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 7.0, P = 0.008 for year): the proportion was higher under long days than under short days and was higher in 2017 than in 2016 (Fig. 1). The interactions of day length with brood and body size were significant (\({\chi }_{2}^{2}\) = 9.1, P = 0.010 for the former interaction;\({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 6.2, P = 0.013 for the latter). To explore the mechanisms underlying the interactions, statistical analysis was performed separately for different broods and for short and long days during the adult stage.

Effects of brood and day length during the adult stage on egg maturation (proportion of female adults with mature eggs) in 2016 and 2017. The bar heights represent the proportions of female adults with mature eggs; the bars are classified by broods. The numbers above the bars indicate sample sizes. Second- and third-brood females were more likely to develop ovaries under long days, but first-brood females were not (see Table 4)

The analysis of each brood revealed that long days induced higher levels of egg maturation compared with short days in the second and third broods (Table 4; Fig. 1) but not in the first brood. Egg maturation was unrelated to body size in every brood (Table 4), but smaller wasps were more likely to exhibit mature eggs than larger ones when all broods were analyzed together under short days (Table 5; Fig. 2). The brood had a significant effect under both short and long days (Table 5, the third brood was less likely to develop ovaries), although the multiple comparison test did not detect significance between any brood pairs. These analyses suggested the possibility that the body-size difference caused the brood difference under short days. The year had a significant effect on egg maturation in the first brood (Table 4).

Effects of body size (head width) and day length during the adult stage on egg maturation (proportion of female adults with mature eggs) in 2016 and 2017. The bar heights represent the proportions of female adults with mature eggs; the bars are classified by head width. The numbers above the bars indicate sample sizes. ND, no data. Smaller wasps were more likely than larger wasps to develop ovaries under short days (see Table 5)

The emergence day influenced egg maturation among the second-brood females under long days (\({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 9.3, P = 0.002, not presented here in tables or figures): females that emerged earlier were more likely to develop ovaries. However, such a difference was not detected in the first or third brood (\({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 0.2, P = 0.680 for first brood; \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 2.6, P = 0.109 for third brood).

Lipid stores

The day length during the adult stage affected the IRL without interacting with any other factors (Table 6): the IRL was higher under short days than under long days (Fig. 3), was higher in 2016 than in 2017, and was positively correlated with adult size (Fig. 4). The IRL was significantly lower for the first brood than for the third brood (sequential Bonferroni multiple comparison test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Additionally, the IRL did not differ significantly between females with and without mature eggs (Table 6; Fig. 3), which differed from the expectation that it would be lower for females with mature eggs (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018b).

Effects of the brood and photoperiod during the adult stage on the IRL [(lipid stores)/(head width cubed)] among females without and with mature eggs in 2016 and 2017. Data are presented as the mean and SE. The numbers in the bars indicate sample sizes. ND no data. The IRL was higher under short days than under long days and was lower for the first brood than for the third brood (see Table 6 and the text)

Relationship between the IRL [(lipid stores)/(head width cubed)] and body size (head width) under short and long days. IRL values were logarithmically transformed. Lines represent the best-fit linear model estimated for short and long days. The IRL was higher under short days than under long days and was positively correlated with adult size (see Table 6)

The emergence day influenced the IRL among second-brood females (\({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 5.7, P = 0.017; not presented here in tables or figures) independently of the effect of day length (interaction: \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) < 0.001, P = 0.987): later-emerging females were more likely to store lipids. Such an influence was not found for the first or third brood (\({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 0.2, P = 0.680 for first brood; \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\) = 2.6, P = 0.109 for third brood).

Discussion

Taken together with the results of our previous study (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018a), the present findings suggested that the first brood emerged with a strong physiological bias toward the nondiapausing form, while the second and third broods emerged with no bias or an easily reversible bias regarding diapause at the adult stage (see Table 1). In the field, the first-brood females become workers in the presence of the healthy colony, and many second-brood P. jokahamae adults also become workers (Tsuchida 1991; Yoshimura et al. 2019). Thus, workers on the nest include those with and without a physiological bias toward the nondiapausing form at emergence. Moreover, the present results repudiate the idea that gynes (diapausing females) always emerge after a certain day, which is estimated to be around the first emergence day of males in many species (Table 1; Metcalf 1980; Suzuki 1986; Toth et al. 2009). Reeve et al. (1998) observed that many first-brood females of Polistes fuscatus left their natal nests within a few days of emergence, probably to overwinter and become foundresses the following spring. However, such early dispersal from the natal nest was not observed among first-brood females of P. jokahamae colonies under field and semi-field conditions (Yoshimura et al. 2019). In addition, the present study suggests that first-brood females of P. jokahamae do not overwinter, even when they are separated from the nests.

The first brood emerged with a strong bias toward the nondiapausing form in the present study. However, this phenomenon was not found in laboratory-reared colonies (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018b). Given that the colonies were collected before the emergence of the first female and were reared in temperature- and photoperiod-controlled rooms with sufficient food (honey and moth larvae) in the previous experiments, there were two possible explanations for the difference: (1) the preimaginal diapause-determining factor is gradual changes in day length during the immature stage, and the laboratory-reared first brood did not experience such changes; or (2) the preimaginal diapausing-determining factor is body size or physiological characteristics related to body size. The present analysis did not reveal which explanation is correct because the first-brood females were smaller than the other-brood females, causing a multicollinearity problem. The former explanation was supported by the fact that females that emerged later were more likely to enter diapause in the second brood, while the latter explanation was supported by the first brood being smaller than the other broods in the present experiments but not in the previous experiments (Yoshimura and Yamada unpubl.). Specific experiments will be required to allow a conclusion to be reached: both of the above-mentioned factors may be effective predictive variables. It would be fruitful to determine the response of emerging adults to the photoperiod after placing larvae and/or pupae under treatments, such as different food supplies or day lengths. Hunt and colleagues (Rossi and Hunt 1988; Karsai and Hunt 2002; Hunt and Amdam 2005; Judd et al. 2015) investigated how food availability during the larval stage influenced caste fate. The experimental results were complex. For example, restricted food availability produced females that were more likely to exhibit mature eggs (biased toward the nondiapausing form) but that emerged with larger lipid stores (biased toward the diapausing form) (Judd et al. 2015). These authors did not consider the effects of the photoperiod and reared experimental wasps under constant long days (an LD of 16:8 h). Consideration of the photoperiod might produce clearer results.

The effects of day length on the caste fate of P. jokahamae definitely contrasted with those found in P. metricus (Bohm 1972). In P. metricus, the second and third broods emerged with PCB toward gynes (diapausing form), while the first brood emerged with no bias or easily reversible bias toward workers (nondiapausing form). One possible reason for the difference between P. jokahamae and P. metricus is that the first brood emerges later in P. metricus than in P. jokahamae (Bohm 1972; the first brood of P. metricus emerged in mid- and late June). The pattern of the appearance of PCB found in different broods of P. metricus appears to be adaptive for paper wasps with shorter periods of colony activity. The second and third broods are thought to always enter diapause in the field due to strong PCB. The first brood may also enter diapause when it emerges later than usual due to cooler temperatures. It should be noted that P. metricus is widely distributed from Florida to New York State in the US (Buck et al. 2008). The populations in southern areas may exhibit similar patterns of PCB appearance to that in P. jokahamae. Interestingly, no workers are present in Polistes biglumis nests found in alpine areas, while workers are present in warmer mountain areas (Fucini et al. 2009, 2014). This situation may represent an extreme case of adaptation to a shorter activity period.

The second brood of P. metricus develops ovaries when JH is applied (Bohm 1972), suggesting that egg maturation is regulated by JH; such a system is widespread in insects, including other paper wasps, such as Ropalidia marginata and Polistes dominulus (Robinson and Vargo 1997; Jandt and Toth 2015; Kapheim 2017). Tibbetts and Izzo (2009) and Tibbetts et al. (2011) reported that the relationship between egg maturation and the level of JH changes depending on the social status and body size of the focal individuals in P. dominulus. This suggests the possibility that the relationship also changes depending on day length during the adult stage. However, our team (Yoshimura, Yamada, and Sasaki unpubl.) suggested another possibility. We have revealed that the brain levels of two biogenic amines, tyramine and dopamine, were positively correlated with egg maturation in P. jokahamae and that the brain level of tyramine responded to photoperiod during the adult stage, but that of dopamine did not. This suggests that tyramine regulates egg maturation in response to photoperiod. However, the photoperiod may also influence egg maturation through the JH signaling pathway (see Miki et al. 2020) in P. jokahamae. This is partially supported by the fact that JH regulates the level of dopamine in Polistes chinensis antennalis (Tsuchida et al. 2020). Unfortunately, the level of JH was not determined in the above study. Whether JH is involved in caste-related physiological responses to photoperiod in paper wasps requires further study.

Piekarski et al. (2018) hypothesized that the shared ancestor of Polistinae and Vespinae had workers with PCB toward workers at emergence, but the present study suggests the possibility that the ancestor had workers who emerged without PCB as well. The caste fate of the females emerging without PCB would be determined mainly by colony-related factors during the adult stage. Since the ancestor is considered to have been distributed in a tropical area (Santos et al. 2015), environmental factors, such as photoperiod and temperature, do not appear to be important. Social situations (e.g. subordinate females are less likely to get food) are as likely to change behavioral and physiological caste-related characteristics as body size. This is because the two kinds of changing process appeared to occur without genetic changes and to be closely related to the reproduction-related responses conserved in most insects, including solitary wasps: females are more likely to develop ovaries and produce more eggs when they are larger and greater amounts of nutrients are available (Cowan 1981; Honěk 1993; Tibbetts et al. 2013; Kapheim 2017).

We observed that many of the wasps categorized as females without mature eggs exhibited nearly mature oocytes under long days. The IRL of all broods, including the first brood, was higher under short days than under long days. In addition, the IRL was not higher among females without mature eggs than among females with mature eggs. Our previous study (Yoshimura and Yamada 2018a) revealed that the IRL was approximately 0.14 mg/mm3 among second- and third-brood females just after emergence. This value was similar to or higher than the IRL among the females reared for 2 weeks in the present study. This finding suggests that most females, including diapausing females, show no increase in the IRL for 2 weeks after emergence, although some females use some of their lipid stores for egg maturation and suppress the increase in the average IRL. Yoshimura (unpubl.) discovered that females collected in the field in early winter exhibited an IRL of approximately 0.28 mg/mm3. Our preliminary experiment (Yoshimura and Yamada unpubl.) in which females emerging from nests collected in the field were reared for 4 weeks according to the same procedures used in the present study showed that many second- and third-brood females without mature eggs exhibited an IRL of approximately 0.28 mg/mm3 under short days and that up to 80% of the first-brood females exhibited mature eggs under long days. These findings suggest that most of the females that will finally enter diapause show no substantial increase in lipid stores for 2 weeks after emergence. The females appeared to decide to enter diapause after spending a few weeks receiving cues related to caste fate (i.e. diapause) determination, including day length and colony conditions.

The proportion of female adults with mature eggs in the first brood was greater in 2017 than in 2016. Body size had no effect on the proportion in the first brood. The emergence days did not differ in different years with no effect on the proportion. Thus, the yearly difference in the proportion was considered to be caused by other factors. One possible factor was the yearly difference in the quality and quantity of food that the individuals received at different stages of the larval period. This may have caused the difference in the amount of JH released and the physiological differences among the emerging females between the two years (Kapheim 2017). However, it should be noted that the difference between years might decrease or even disappear if the emerging females were reared for a longer period. This is because our preliminary experiment, which was mentioned in the previous paragraph, discovered that when first-brood females were reared for 4 weeks under long days, the proportion of females with mature eggs reached approximately 80% in each of the two years studied.

The present study strongly suggests that the rearing of different-brood adults under different photoperiods is an effective way to reveal the strength of PCB. The same experimental procedures are expected to be performed in many other paper wasp species. Then, the following further questions should be raised to explain the evolutionary process of eusociality: how photoperiod interacts with other PCB-generating factors, such as colony-related factors, and how photoperiod induces physiological changes related to PCB. We have already started experiments to solve these questions and to determine the effects of photoperiod on caste-fate determination using other paper wasp species. We firmly believe that many novel findings are waiting to be disclosed.

References

Berens AJ, Hunt JH, Toth AL (2015) Nourishment level affects caste-related gene expression in Polistes wasps. BMC Genomics 16:235. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-015-1410-y

Bohm MK (1972) Effects of environment and juvenile hormone on ovaries of the wasp, Polistes metricus. J Insect Physiol 18:1875–1883. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1910(72)90158-8

Boomsma JJ, Gawne R (2018) Superorganismality and caste differentiation as points of no return: how the major evolutionary transitions were lost in translation. Biol Rev 93:28–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12330

Buck M, Marshall SA, Cheung DKB (2008) Identification Atlas of the Vespidae (Hymenoptera, Aculeata) of the northeastern Nearctic region. Can J Arthropod Identif 5:1–492. https://doi.org/10.3752/cjai.2008.05

Carpenter JM (1991) Phylogenetic relationships and the origin of social behavior in the Vespidae. In: Ross KG, Matthews RW (Eds.). The social biology of wasps. New York. pp 7–32

Cowan DP (1981) Parental investment in two solitary wasps Ancistrocerus adiabatus and Euodynerus foraminatus (Eumenidae: Hymenoptera). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 9:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00293580

Craig R (1983) Subfertility and the evolution of eusociality by kin selection. J Theor Biol 100:379–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(83)90436-8

Eickwort K (1969) Separation of the castes of Polistes exclamans and notes on its biology (Hym.: Vespidae). Insect Soc 16:67–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02224464

Evans HE, West-Eberhard MJ (1970) The wasps. Univ of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Field J, Foster W (1999) Helping behaviour in facultatively eusocial hover wasps: an experimental test of the subfertility hypothesis. Anim Behav 57:633–636. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1999.0995

Fucini S, Bona VD, Mola F, Piccaluga C, Lorenzi MC (2009) Social wasps without workers: geographic variation of caste expression in the paper wasp Polistes biglumis. Insect Soc 56:347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-009-0030-4

Fucini S, Uboni A, Lorenzi MC (2014) Geographic variation in air temperature leads to intraspecific variability in the behavior and productivity of a eusocial insect. J Insect Behav 24:403–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10905-013-9436-y

Futuyma DJ, Kirkpatrick M (2017) Evolution, 4th edn. Sunderland, MA

Gadagkar R (1991) Belonogaster, Mischocyttarus, Parapolybia, and independent-founding Ropalidia. In: Ross KG, Matthews RW (Eds.). The social biology of wasps. New York. pp 149–190

Haggard CM, Gamboa GJ (1980) Seasonal variation in body size and reproductive condition of a paper wasp, Polistes metricus (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Can Entomol 112:239–248. https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent112239-3

Holm S (1979) A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/4615733

Honěk A (1993) Intraspecific variation in body size and fecundity in insects: a general relationship. Oikos 66:483–492. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544943

Hunt JH (1991) Nourishment and the evolution of the social Vespidae. In: Ross KG, Matthews RW (Eds.). The social biology of wasps. New York. pp 426–450

Hunt JH (2006) Evolution of castes in Polistes. Ann Zool Fennici 43:407–422

Hunt JH (2007) The evolution of social wasps. Oxford Univ Press, New York

Hunt JH (2012) A conceptual model for the origin of worker behaviour and adaptation of eusociality. J Evol Biol 25:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02421.x

Hunt JH, Amdam GV (2005) Bivoltinism as an antecedent to eusociality in the paper wasp genus Polistes. Science 308:264–267. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1109724

Hunt JH, Kensinger BJ, Kossuth JA, Henshaw MT, Norberg K, Wolschin F, Amdam GV (2007) A diapause pathway underlies the gyne phenotype Polistes wasps, revealing an evolutionary route to caste-containing insect societies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:14020–14025. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705660104

Jandt JM, Toth AL (2015) Physiological and genomic mechanisms of social organization in wasps (Family: Vespidae). Adv Insect Physiol 48:95–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aiip.2015.01.003

Jandt JM, Suryanarayanan S, Hermanson JC, Jeanne RL, Toth AL (2017) Maternal and nourishment factors interact to influence offspring developmental trajectories in social wasps. Proc R Soc B 284:20170651. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0651

Jeanne RL (2003) Social complexity in the Hymenoptera, with special attention to the wasps. In: Kikuchi T, Azuma N, Higashi S (eds) Genes, behaviors and evolution of social insects. Sapporo, Hokkaido, pp 81–131

Jeanne RL, Suryanarayanan S (2011) A new model for caste development in social wasps. Comm Integr Biol 4:373–377. https://doi.org/10.4161/cib.4.4.15262

Judd TM (2018) Effect of the presence of brood on the behavior and nutrient level of emerging individuals in field colonies of Polistes metricus. Insect Soc 65:171–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-017-0599-y

Judd TM, Teal PEA, Hernandez EJ, Choudhury T, Hunt JH (2015) Quantitative differences in nourishment affect caste-related physiology and development in the paper wasp Polistes metricus. PLoS ONE 10:e0116199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116199

Kapheim KM (2017) Nutritional, endocrine, and social influences on reproductive physiology at the origins of social behavior. Curr Opin Insect Sci 22:62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.018

Karsai I, Hunt JH (2002) Food quantity affect traits of offspring in the paper wasp Polistes metricus (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Environ Entomol 31:99–106. https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-31.1.99

Kelstrup HC, Hartfelder K, Esterhuizen N, Wossler TC (2017) Juvenile hormone titers, ovarian status and epicuticular hydrocarbons in gynes and workers of the paper wasp Belonogaster longitarsus. J Insect Physiol 98:83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2016.11.014

Liebert AE, Johnson EN, Switz GT, Starks PT (2004) Triploid females and diploid males: underreported phenomena in Polistes wasps? Insect Soc 51:205–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-004-0754-0

Metcalf RA (1980) Sex ratios, parent-offspring conflict, and local competition for mates in the social wasps Polistes metricus and Polistes variatus. Am Nat 166:642–654. https://doi.org/10.1086/283655

Michener CD (1964) Reproductive efficiency in relation to colony size in hymenopterous societies. Insect Soc 11:317–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02227433

Miki T, Shinohara T, Chafino S, Noji S, Tomioka K (2020) Photoperiod and temperature separately regulate nymphal development through JH and insulin/TOR signaling pathways in an insect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:5525–5531. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1922747117

Miyano S (1991) Worker reproduction and related behavior in orphan colonies of a Japanese paper wasp, Polistes jadwigae (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). J Ethol 9:135–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02350218

Noll FB, Wenzel JW, Zucchi R (2004) Evolution of caste in neotropical swarm-founding wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae; Epiponini). Am Mus Novit 3467:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0082(2004)467%3c0001:EOCINW%3e2.0.CO;2

O’Donnell S (1998) Reproductive caste determination in eusocial wasps (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Ann Rev Entomol 43:323–346. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.323

Oster GF, Wilson EO (1978) Caste and ecology in the social insects. Princeton, NJ

Page RE, Post DC, Metcalf RA (1989) Satellite nests, early males, and plasticity of reproductive behavior in a paper wasp. Am Nat 134:731–748. https://doi.org/10.1086/285008

Pardi L (1948) Dominance order in Polistes wasp. Physiol Zool 21:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1086/physzool.21.1.30151976

Piekarski PK, Carpenter JM, Lemmon AR, Lemmon EM, Sharanowski BJ (2018) Phylogenomic evidence overturns current conceptions of social evolution in wasps (Vespidae). Mol Biol Evol 35:2097–2109. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy124

R Foundation (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Available at http://www.R-project.org/

Reeve HK, Peters JM, Nonacs P, Starks PT (1998) Dispersal of first “workers” in social wasps: causes and implications of an alternative reproductive strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13737–13742. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.23.13737

Rice WR (1989) Analyzing tables of statistical test. Evolution 43:223–225. https://doi.org/10.23007/2409177

Robinson GW, Vargo EL (1997) Juvenile hormone in adult eusocial Hymenoptera: gonadotropin and behavioral pacemaker. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 35:559–583. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6327(1997)35:4%3c559::AID-ARCH13%3e3.0.CO;2-9

Rossi AM, Hunt JH (1988) Honey supplementation and its developmental consequences: evidence for food limitation in a paper wasp, Polistes metricus. Ecol Entomol 13:437–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1988.tb00376.x

Santos BF, Payne A, Pickett KM, Carpenter JM (2015) Phylogeny and historical biogeography of the paper wasp genus Polistes (Hymenoptera: Vespidae): implications for the overwintering hypothesis of social evolution. Cladistics 31:535–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/cla.12103

Smith CR, Toth AL, Smith CR, Toth AL, Suarez AV, Robinson GE (2008) Genetic and genomic analyses of the division of labour in insect societies. Nat Rev Genet 9:735–748. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2429

Solís CR, Strassmann JE (1990) Presence of brood affects caste differentiation in the social wasp, Polistes exclamans Viereck (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Funct Ecol 4:531–541. https://doi.org/10.2307/2389321

Strassmann JE (1981) Evolutionary implications of early male and satellite nest production in Polistes exclamans colony cycles. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 8:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00302844

Strassmann JE, Lee RE, Rojas RR, Baust JG (1984) Caste and sex differences in cold-hardiness in the social wasps, Polistes annularis and Polistes exclamans (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Insect Soc 31:291–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02223613

Suzuki T (1986) Production schedules of males and reproductive females, investment sex ratios, and worker-queen conflict in paper wasps. Am Nat 128:366–378. https://doi.org/10.1086/284568

Tibbetts EA (2007) Dispersal decisions anTibbetts EA (2007) Dispersal decisions and predispersal behavior in Polistes paper wasp ‘workers.’ Behav Ecol Sociobiol 61:1877–1883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-007-0427-x

Tibbetts EA, Izzo A (2009) Endocrine mediated phenotypic plasticity: condition-dependent effects of juvenile hormone on dominance and fertility of wasp queens. Horm Behav 56:527–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.09.003

Tibbetts EA, Levy S, Donajkowski K (2011) Reproductive plasticity in Polistes paper wasp workers and the evolutionary origins of sociality. J Insect Physiol 57:995–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.04.016

Tibbetts EA, Mettler A, Donajkowski K (2013) Nutrition-dependent fertility response to juvenile hormone in non-social Euodynerus foraminatus wasps and the evolutionary origin of sociality. J Insect Physiol 59:339–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.11.010

Toth AL, Bilof KBJ, Henshaw MT, Hunt JH, Robinson GE (2009) Lipid stores, ovary development, and brain gene expression in Polistes metricus females. Insect Soc 56:77–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-008-1041-2

Tsuchida K (1991) Temporal behavioral variation and division of labor among workers in the primitively eusocial wasp, Polistes jadwigae Dalla Torre. J Ethol 9:129–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02350217

Tsuchida K, Saigo T, Asai K, Okamoto T, Ando M, Ando T, Sasaki K, Yokoi K, Watanabe D, Sugime Y, Miura T (2020) Reproductive workers insufficiently signal their reproductive ability in a paper wasp. Behav Ecol 31:577–590. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arz212

West-Eberhard MJ (1975) The evolution of social behavior by kin selection. Q Rev Biol 50:1–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/408298

West-Eberhard MJ (1978) Polygyny and the evolution of social behavior in wasps. J Kansas Entomol Soc 51: 832–856. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25083873

Wheeler DE (1986) Developmental and physiological determinants of caste in social Hymenoptera: evolutionary implications. Am Nat 128:13–34. https://doi.org/10.1086/284536

Wilson EO (1971) The insect societies. Cambridge

Wilson EO (1975) Sociobiology: the new synthesis. Cambridge

Yoshimura H, Yamada YY (2018a) The first brood emerges smaller, lighter, and with lower lipid stores in the paper wasp Polistes jokahamae (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Insec Soc 65:473–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-018-0636-5

Yoshimura H, Yamada YY (2018b) Caste-fate determination primarily occurs after adult emergence in a primitively eusocial paper wasp: significance of the photoperiod during the adult stage. Sci Nat 105:15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-018-1541-5

Yoshimura H, Yamada J, Yamada YY (2019) The queen of the paper wasp Polistes jokahamae (Vespidae: Polistinae) is not aggressive but maintains her reproductive priority. Sociobiology 66:166–178. https://doi.org/10.13102/sociobiology.v66i1.3577

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS (2010) A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol Evol 1:3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x

Acknowledgements

We thank the journal’s associate editor (MC Lorenzi) and two anonymous reviewers for constructive and helpful suggestions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshimura, H., Yamada, Y.Y. Preimaginal caste-related bias in the paper wasp Polistes jokahamae is limited to the first brood. Insect. Soc. 68, 133–143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-020-00805-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00040-020-00805-1