Abstract

Objectives

This paper examines the opportunities and barriers that the South Australian Health in all Policies (SA HiAP) approach encountered when seeking to establish a whole-of-government response to promoting healthy weight.

Methods

The paper draws on data collected during 31 semi-structured interviews, analysis of 113 documents, and a program logic model developed via workshops to show the causal links between strategies and anticipated outcomes.

Results

A South Australian Government target to increase healthy weight was supported by SA HiAP to develop a cross-government response. Our analysis shows what supported and hindered implementation. A combination of economic and systemic framing, in conjunction with a co-benefits approach, facilitated intersectoral engagement. The program logic shows how implementation can be expected to contribute to a population with healthy weight.

Conclusions

The HiAP approach achieved some success in encouraging a range of government departments to contribute to a healthy weight target. However, a comprehensive approach requires national regulation to address the commercial determinants of health and underlying causes of population obesity in addition to cross-government action to promote population healthy weight through regional government action.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is a major global preventable public health problem leading to chronic disease, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke and cancer (World Health Organization 2018). Obesity has tripled since 1975. In 2016, over 1.9 billion adults (39%) were overweight, with 650 million (13%) of these being obese. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among 5 and 19 year olds has risen from 4% in 1975, to over 18% in 2016 (World Health Organization 2018).

In 2017–2018, 67.0% of Australians aged 18 years and over were overweight or obese, with 35.6% categorised as overweight and 31.3% as obese. Since 2014–2015, the proportion of adults aged 18 years and over who were overweight or obese increased from 63.4 to 67.0%. This change was driven by the increase in the proportion of adults categorised as obese, which increased from 27.9 to 31.3% (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019).

South Australia (SA) had the second highest prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australia (69.7%). In SA, between 2007–2008 and 2014–2015, the period of this study, there was a 7% increase in obesity prevalence, while the combined overweight and obesity prevalence among SA children declined by 1.4% between 2007–2008 and 2014–2015 (Huse et al. 2018).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people living outside major cities, and those in lower socio-economic circumstances are more likely to be overweight. In 2012–2013, after adjusting for differences in age structure, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults were 1.2 times as likely to be overweight and 1.6 times as likely to be obese as non-Aboriginal Australians. In 2014–2015, 74% of men and 64% of women living in outer regional or remote areas of Australia were overweight or obese compared to 69% of men and 53% of women living in major cities. In 2014–2015, 61% of women in the lowest socio-economic group were overweight or obese compared to 48% in the highest socio-economic group (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017).

Traditionally, obesity has been viewed as a result of individual choices—the over-consumption of the wrong foods and insufficient physical activity. However, health promotion responses that solely focus on individuals and behaviour change have had limited sustainability and have not been transferable (Friel et al. 2007; Rodgers et al. 2018). There is now widespread recognition of the importance of ‘obesogenic environments’ (Swinburn et al. 1999) as a cause of obesity, including the impact of the built and food environments on population weight (Norman et al. 2016; Townshend and Lake 2017). There is a growing understanding of the role that social, environmental, economic and commercial factors play in shaping individual diet and physical activity choices, and therefore of the importance of population responses to obesity to influence complex obesogenic environments (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017; UK Government Office for Science 2007). There is an accompanying recognition of the role of supportive policies across sectors to address the fundamental causes of overweight and obesity, including in health, agriculture, transport, education, urban planning, and food processing, distribution and marketing (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2018; World Health Organization 2018). Most of the determinants that drive obesity are outside the direct control of the health system. Consequently, intersectoral responses are important (Friel et al. 2007; Rodriguez et al. 2017).

Recent research has recognised the role of transnational corporations in driving global patterns of disease. The role of the commercial determinants of health (Hastings 2012) and the global neoliberal economic system that prioritises profits over health has become an increasing focus in the literature, with recognition of their role in the rise of non-communicable diseases (Buse et al. 2017; Knai et al. 2018). The World Health Organization Shanghai Declaration recognised the importance of commercial factors in driving the global obesity epidemic (World Health Organization 2017). In relation to overweight and obesity, the profit-driven commercially produced food and drink industries use pricing, marketing and distribution strategies to influence consumption (McKee and Stuckler 2016). Otero (2018) describes ‘the neoliberal diet’, which he sees results in ‘healthy profits and unhealthy people’. Powerful transnational corporations have increasingly become central to public health policymaking (Knai et al. 2018).

Context

SA is a state within the federated nation of Australia. In 2018, SA had a population of 1.7 million people, with 77% living in Adelaide and its environs. It has a history of social policy innovation, including the Adelaide Thinkers in Residence program, which resulted in the introduction of the Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach in SA (Baum et al. 2015).

HiAP is an intersectoral approach promoted by the World Health Organization that provides a foundation for health policymakers to work with other sectors to consider the potential health and equity implications of their policies, while advancing partner agencies’ objectives (Leppo 2008). Implementation of HiAP commenced in SA in 2007 and was linked to South Australia’s Strategic Plan (SASP) (Government of South Australia 2007). The HiAP approach has continued to operate and adapt in SA since then (Williams and Galicki 2017).

The then SA Labor Government identified key SASP targets and allocated responsibility for achieving these to specific departments, requiring interdepartmental collaboration to progress the targets, and held departmental chief executives accountable to Cabinet for outcomes. SASP included targets relating to healthy weight and physical activity, which were modified between the 2007 and 2011 versions of SASP (see Table 1).

The HiAP unit was invited by the Health Department to undertake a project to support achievement of the SASP healthy weight target. While Health was responsible for the healthy weight target, the links between healthy weight, increased physical activity and reduced consumption of unhealthy foods led the HiAP unit to work with other sectors on identifying projects that would support increased physical activity and healthy eating.

At the time the HiAP unit was concluding its healthy weight project, the Health Department’s 2006–2010 Eat Well Be Active (EWBA) Strategy was under review. The 2006–2010 version of the Strategy had included some cross-sector strategies, such as introducing healthy food policies into school canteens through the education sector, but was predominantly a health strategy.

The SA HiAP approach resulted in the negotiation of policy actions across government to support the achievement of SASP’s healthy weight and physical activity targets, while also seeking whole-of-government policy coherence on healthy weight, and outcomes with co-benefits for partner agencies. The endorsed strategies negotiated by the HiAP unit with other agencies were incorporated into a separate section of the 2011–2016 version of the EWBA Strategy and were explicitly identified as arising from HiAP. Agencies endorsed these strategies as part of their core business and received no additional funding for their implementation. Table 2 provides a summary timeline of these policy developments.

In 2012, in response to growing pressure on the State budget the Health Department initiated a review of non-hospital-based services (McCann 2012). Following this review, Health Department funding for health promotion services was cut. This resulted in the majority of the Health Department’s initiatives identified in the EWBA Strategy being de-funded. Despite this, many of the other departments’ strategies, negotiated by the HiAP unit and included in the EWBA Strategy, have continued to be implemented (South Australian Nutrition Network 2018).

This paper describes the HiAP healthy weight project, which negotiated policy initiatives in many sectors. A previous evaluation of the initial stages of the project described the HiAP process of engaging with other sectors and identifying the strategies that these sectors would commit to implementing (Newman et al. 2014). This paper takes this analysis further. It uses data from a five-year evaluation of the SA HiAP approach to provide evidence on the implementation and resultant lessons from the project as a case study of how the SA HiAP approach has influenced policy and action in other sectors to build a whole-of-government response to promoting healthy weight. It presents a program logic model to demonstrate the causal links between HiAP unit-negotiated strategies included in the EWBA Strategy, and projected long-term population healthy weight outcomes.

Methods

This case study is one component of a mixed methods research study on the implementation of the HiAP approach in SA undertaken between 2012 and 2016. The methods used are summarised in Table 3.

Document analysis

Documents included project plans and reports, literature reviews, meeting papers, and briefings. The research team undertook collaborative thematic analysis of documents to reveal information about the project context, aims, processes, actors, activities, outputs and anticipated outcomes.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were guided by pre-prepared interview schedules which built on and were informed by the document analysis. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Early interviews focused on the desktop analysis component of the healthy weight project, and subsequent interviews also sought information about agency commitment and implementation. Collaborative thematic analysis of the interview data by the researchers focused on the facilitators and impediments to the project, participants’ reasons for collaboration, their understanding of links between their agency’s core business and promoting healthy weight, and outcomes for their agency arising from their involvement with HiAP.

Program theory-based evaluation framework

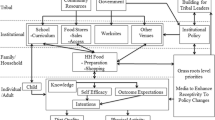

A program theory-based evaluation framework was developed during two workshops with SA Government staff to describe the overall SA HiAP approach. The overarching program logic model for the SA HiAP approach was based on a combination of research evidence from the literature, bureaucratic knowledge and social and political science theories (Lawless et al. 2018). For the purpose of the healthy weight project research case study, the original program logic model was reviewed in the light of the data emerging from our analysis and the published research evidence in relation to promoting healthy weight, and then adjusted to reflect these. This was done in order to demonstrate the links between the strategies adopted by partner agencies as a result of involvement in the project and long-term outcomes that can be anticipated in the future (see Fig. 1).

Data analysis

The research team conducted a collaborative, thematic analysis of the interview transcripts. An initial round of open descriptive coding was undertaken collaboratively to identify central themes in the data, followed by selective coding (Ezzy 2002). This involved team discussion of the data, refinement of themes, comparison of themes from this case study with other data collected during the broader project, and deepening of data analysis by drawing on the literature. Theoretical approaches guiding the broader study were drawn on to deepen understanding of the project processes, the nature of the collaborative relationships and their implications (Lawless et al. 2018).

Results

We now present an overview of the project and then use the framework of the project logic model (Fig. 1) to describe what facilitated and impeded this project in achieving its intended outcomes.

HiAP healthy weight project

The HiAP healthy weight project was undertaken by HiAP staff in two stages—a desktop analysis of other sectors’ reports and policies to identify strategies that could be adapted to address healthy weight and negotiated with other agencies, and implementation of agreed strategies by participating sectors.

Stage 1: Desktop analysis

During the desktop analysis, HiAP staff collaborated with a university social researcher (Newman et al. 2014). Together they reviewed annual reports, policies and strategies of 44 state government departments and divisions for potential policy opportunities aligned with the goal of promoting healthy weight. Nineteen of these departments and divisions were selected, based on the HiAP team’s determination of the policy opportunities and their potential for action. A mapping process was then undertaken to identify which of these departments’ core business could be aligned to promoting healthy weight. Ten departments were directly consulted about policy opportunities. These departments are identified by sector in Table 4. The HiAP team did not invite the participation of the education or the sport and recreation sectors because they were already collaborating with Health on a number of healthy weight strategies, nor the child protection sector because of the crisis-driven nature of its work.

The HiAP team’s desktop analysis took 12 months. It resulted in the development of specific healthy weight policy recommendations that aligned with other departments’ core business. HiAP staff negotiated these recommendations with the departments, including in the areas of active transport, access to healthy food, housing policy, and facilities planning and management (see Table 4). The recommendations were then endorsed by departmental chief executives. A decision was made by the Health Department to incorporate these recommendations into its revised ‘Eat Well Be Active Strategy 2011–2016’ (EWBA Strategy) (Government of South Australia 2011a) as a whole-of-government response to healthy weight. This aligned with Health’s mandate under SASP to lead a collaborative whole-of-government approach to addressing healthy weight.

Stage 2: Implementation of endorsed recommendations

Next, the project implemented the endorsed recommendations. We conducted a series of follow-up interviews to determine which HiAP strategies included in the EWBA Strategy had been implemented by the sectors involved, and to identify lessons about developing and implementing a whole-of-government approach to promoting healthy weight.

We found that full implementation of the HiAP healthy weight project was not completed because of an organisational restructure and the reassignment of responsible HiAP staff to other priorities within Health. Despite this, we were still able to identify a number of project outcomes. Table 4 provides examples of:

-

key policy recommendations that HiAP staff negotiated that were included in the EWBA Strategy

-

strategies identified as implemented

-

longer-term outcomes from these strategies identified by respondents, and anticipated outcomes based on published research evidence

-

unanticipated spin-off activities.

The examples included in Table 4 come from the transport, planning, environment, correctional services, primary industries, and consumer and business services sectors.

The program logic model in Fig. 1 provides the framework for presentation of the findings from this case study.

Strategies

Identified healthy weight strategies aligned with other agencies’ core business

The healthy weight project was the first SA HiAP project that focused on a priority identified as relating to health (and identified as a Health Department priority in SASP), rather than a priority of another agency (Baum et al. 2017; Baum et al. 2019). This was challenging for the HiAP team, who sought to avoid a ‘health imperialist’ approach while still seeking to engage with other agencies on addressing healthy weight (Holt 2018). As a result, HiAP staff adopted the desktop analysis as a new approach, prior to engaging with other sectors. This replaced the typical HiAP process of engagement and negotiation of a topic of concern with another sector, followed by identification of potential aligned health outcomes.

HiAP staff framed the problem of overweight and obesity in terms of a systemic response rather than an individualised biomedical one (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2018; Rushton and Williams 2012) and undertook a literature review of research evidence on policy levers likely to support healthy weight. They then sought opportunities for these policy levers in the existing plans and priorities of other agencies prior to engaging with them (Newman et al. 2014).

Throughout this process, HiAP staff sought to maintain a focus on co-benefits for the other agency. This could be difficult, and they reported ‘some of them dropped off because we couldn’t get that alignment with their core business’. HiAP staff noted that when core business was not directly involved 'it was harder to make the argument' for the agency's involvement. By ensuring the alignment of their proposed strategies with the core business of partner agencies, they were able to gain the support of some agencies that had quite different agendas, including some that were more economically driven, such as the transport, primary industries and planning sectors. However, our data include two examples of where HiAP staff proposed what they perceived as health policy ‘gold standard’ strategies—requiring contracted services to provide healthy food options for clients and removing unhealthy food advertising from public transport facilities. In these instances, the HiAP unit’s proposals did not align with the partner agencies’ core business and interests, and were not supported. Significantly, the finance sector did not engage with the project. A lack of alignment with agencies’ core business and interests appears to reduce the likelihood of a supportive response. This also suggests that when commercial imperatives are considered they win over health considerations.

Developed partnerships with agencies with aligned interests that could promote healthy weight

Respondents from other sectors identified facilitators for their involvement as including prior working relationships with HiAP and health promotion staff, sharing common interests, and the presence of a supportive authorising environment and leadership. The healthy weight project strengthened existing partnerships between the HiAP unit and other departments, and created opportunities for establishing partnerships with new collaborators:

there weren’t a lot of synergies between what we did and what the Health Department did […] and I think this is what the value of this whole Health in All Policies and Eat Well Be Active Strategy work has done, is actually identified that there are synergies. So our relationship with Health is increasing more now obviously, but at the time it was ‘Health? Gosh, what are the links there?’ (Environment).

Utilised governance systems that connect HiAP work with senior decision-makers

Analysis of our data shows that a policy window (Kingdon 2011) opened for promoting healthy weight, supported by increasing government concern about the worsening SA trends in overweight and obesity, and raised public awareness of the ‘obesity epidemic’.

The HiAP healthy weight project was supported by an authorising environment created by the SASP healthy weight target, and was mandated at the political level because of prioritisation of the issue by the then State Premier and Health Minister. Accountability requirements of SASP meant that senior decision-makers prioritised intersectoral action on healthy weight.

The policy window that allowed Health to address healthy weight also created opportunities for other departments to progress their interests where these aligned with that aim. For example, Transport progressed its interest in establishing cycling tracks, and Environment progressed its interest in promoting increased community use of national parks (see Table 4).

Impacts on policy environment

Of 11 non-Health interview respondents, 9 reported that their agencies had developed an understanding of the health implications of their policies, including the potential role for their agency to promote healthy weight. They also recognised the importance of an intersectoral approach to addressing obesity and attributed this to their involvement with HiAP and the SASP healthy weight target. One noted that they thought ‘a lot of our people now recognise that trying to achieve health outcomes in our work is critical ... it’s becoming more mainstream.’

Our data also show that there is a direct link between the Environment and Planning Departments’ involvement in the HiAP healthy weight project and their Chief Executives signing Public Health Partner Authority agreements with Health under the South Australian Public Health Act 2011 to continue joint work to address agreed public health priorities of mutual concern.

Outcomes

Table 4 summarises the longer-term outcomes identified by our interview respondents, as well as outcomes that could be anticipated from implementation of the recommendations, based on the project’s program logic, assuming an ongoing supportive political and bureaucratic context.

Departmental restructures and budget cuts were experienced across the SA public sector at the time that agencies were intending to implement the agreed strategies. Health cut its health promotion funding and services, resulting in the cessation of activities it had committed to implement in the EWBA Strategy. Departmental restructures also affected other agencies’ capacity and willingness to implement recommendations, and budget cuts led to a return to a narrower understanding of ‘core business’. A respondent explained:

I think it’s been incredibly difficult with the changes we’ve faced over the last three or four years with budget cuts and restructures for the organisation to progress this sort of culture change initiative with any sort of continuity. From my perspective I think that it’s individuals who have championed it rather than anything that’s systemic (Environment).

Outcomes varied greatly, with positive examples including creating community gardens to increase access to healthy foods and social contact, building bicycle tracks and accessible walking trails to encourage greater use of national parks, and increasing opportunities for active transport. Table 4 includes a number of unanticipated spin-off activities identified by our respondents as resulting from the healthy weight project, such as the participation of HiAP staff in development of the 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide and SA’s new planning legislation.

Discussion

A whole-of-government approach seeks to work across department boundaries to provide integrated responses to shared problems.

A whole-of-government response may not necessarily require the collaboration of every government agency, but should include engagement of all those agencies that would enable the achievement of policy coherence and a comprehensive, coordinated response to a shared policy problem.

This paper has considered the process of how the SA Government came to adopt and implement a whole-of-government response to promoting healthy weight. Our data have revealed multiple factors that supported and impeded the development and implementation of this response. These are summarised in Table 5.

HiAP staff expressed initial concern about undertaking the healthy weight project because it could be construed as ‘health imperialism’ by the agencies they were approaching (Holt 2018). Health imperialism was perceived by HiAP staff to be an impediment to a productive collaborative process. However, this risk was managed through maintenance of a co-benefits approach by extending or focusing other agencies’ existing priorities where these could be aligned with promoting healthy weight. Six respondents from other sectors said that their agency would have implemented the strategies that were included in the EWBA Strategy even without the involvement of the HiAP unit, because these strategies were already part of their agency’s core business. This raises the question of the difference that the healthy weight project made to participating agencies’ existing plans. HiAP’s contribution was to strengthen and clarify the health focus of these strategies, including building recognition of other sectors’ roles in addressing the social determinants of health (Baum et al. 2019).

SASP’s healthy weight target supported the HiAP unit’s focus on identifying population-focused responses that also achieved other sectors’ aims. The HiAP unit also used an economic framing when presenting the case for a whole-of-government response to healthy weight. Economic framing enabled a focus on the economic consequences for the state of the ‘obesity epidemic’, and was consistent with the growing concern within the SA Government about population obesity and implications for the health budget. Economic framing created a sense of crisis which resonated with policy actors from other sectors (Rushton and Williams 2012). The HiAP unit used economic framing to argue that every agency had an interest in promoting healthy weight as part of their core business. Combining economic framing with a systemic framing of healthy weight supported the unit’s arguments for population-based intersectoral responses (Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2018).

Alongside the framing of healthy weight in ways that would foster acceptance of the need for intersectoral responses, the HiAP unit’s co-benefits approach, through which they presented other agencies with policy solutions that were closely aligned to the agency’s interests, was critical to their effective engagement with other sectors (Baum et al. 2017; Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. 2018). However, the co-benefits approach also largely limited the strategies that HiAP staff proposed to those that were closely aligned to partner agencies’ existing priorities, and rarely challenged them to act beyond their core business, for example, to consider the equity dimensions of overweight and obesity (in particular the impact of poverty) (Chaufan et al. 2015; van Eyk et al. 2017). Engagement was resisted in the limited number of cases where the strategies that HiAP staff proposed were beyond the core business of partner agencies or challenged commercial interests.

While adult prevalence of overweight and obesity in SA continues to rise, there is evidence that childhood prevalence has declined slightly (− 1.4% between 2007–2008 and 2014–2015). Of course, this cannot be attributed to the HiAP healthy weight project alone. While Health withdrew support for its community nutrition programmes, a number of recommendations from the whole-of-government section of the EWBA Strategy arising from the healthy weight project have continued to be implemented.

As a state regional jurisdiction within a federated nation and a global context, action within SA cannot alone influence the rising prevalence of overweight and obesity, however effective its actions. Comprehensively addressing healthy weight requires national action to address the commercial determinants of health. Multinational food and beverage corporations and the global food system require a national policy response and regulation, for example through a sugar tax on carbonated drinks (Duckett et al. 2016). Without this, the impact of regional-level action is inevitably limited (Baker et al. 2017; Roberto et al. 2015). The need for national regulation was recognised by the SA Health Minister at the time of the HiAP healthy weight project, and he raised a sugar tax proposal at the national level which did not gain traction. Internationally, it is recognised that addressing rising obesity levels is critical to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. This requires a strong policy response to the commercial and political determinants of health regionally, nationally and globally.

Conclusions

This paper has documented SA HiAP's partial success in making healthy weight a priority with other sectors. Multiple departments signed off on recommendations for action, a number of which have been implemented. This happened because the HiAP unit worked with agencies with aligned interests in such a way that both could achieve their core business. They also had a clear mandate and supportive authorising environment, and had leaders and champions in other sectors who recognised the mutual benefit of supporting shared goals.

Public sector restructuring and budget cuts meant that not all strategies were implemented. Despite this, the HiAP approach contributed to establishing an intersectoral response to increasing the percentage of the population with healthy weight in SA. The agencies recognised the value and relevance of their contributions to achieving population healthy weight targets and sustaining actions that will contribute to this outcome over the long term. However, the work of state government agencies to increase healthy weight is limited in the face of the powerful commercial determinants of obesity. These determinants concern the patterns of trade and the growth of a transnational food industry which markets and produces high fat and sugar food and beverages (Otero 2018). To address these determinants requires that regional approaches, such as the HiAP healthy weight project, are complemented by national and global efforts.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019) National Health Survey: first results 2017–2018 (cat. no. 4364.0.55.001). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2017-18~Main%20Features~Overweight%20and%20obesity~90#. Accessed 11 July 2019

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017) A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia 2017. Cat. no. PHE 216. AIHW, Canberra

Baker P, Gill T, Friel S, Carey G, Kay A (2017) Generating political priority for regulatory interventions targeting obesity prevention: an Australian case study. Soc Sci Med 177:141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.047

Baum F, Lawless A, MacDougall C, Delany T, McDermott D, Harris E, Williams C (2015) New norms new policies: did the Adelaide Thinkers in Residence scheme encourage new thinking about promoting well-being and Health in All Policies? Soc Sci Med 147:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.031

Baum F, Delany-Crowe T, MacDougall C, Lawless A, van Eyk H, Williams C (2017) Ideas, actors and institutions: lessons from South Australian Health in All Policies on what encourages other sectors’ involvement. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4821-7

Baum F, Delany-Crowe T, MacDougall C, van Eyk H, Lawless A, Williams C, Marmot M (2019) To what extent can the activities of the South Australian Health in All Policies initiative be linked to population health outcomes using a program theory-based evaluation? BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6408-y

Buse K, Tanaka S, Hawkes S (2017) Healthy people and healthy profits? Elaborating a conceptual framework for governing the commercial determinants of non-communicable diseases and identifying options for reducing risk exposure. Glob Health 13:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0255-3

Chaufan C, Yeh J, Ross L, Fox P (2015) You can’t walk or bike yourself out of the health effects of poverty: active school transport, child obesity, and blind spots in the public health literature. Crit Public Health 25:32–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2014.920078

Duckett S, Swerissen H, Wiltshire T (2016) A sugary drinks tax: recovering the community costs of obesity. Grattan Institute, Melbourne

Ezzy D (2002) Qualitative analysis—practice and innovation. Allen and Unwin, Sydney

Friel S, Chopra M, Satcher D (2007) Unequal weight: equity oriented policy responses to the global obesity epidemic. BMJ 335:1241–1243. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39377.622882.47

Government of South Australia (2007) South Australia’s Strategic Plan 2007. Government of South Australia, Adelaide

Government of South Australia (2011a) Eat well be active strategy for South Australia 2011–2016. Department of Health, Public Health and Clinical Systems Division, Adelaide

Government of South Australia (2011b) South Australia’s Strategic Plan 2011. Government of South Australia, Adelaide

Hastings G (2012) Why corporate power is a public health priority. BMJ 345:e5124. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5124

Holt DH (2018) Rethinking the theory of change for Health in All Policies: comment on “Health promotion at local level in Norway: the use of public health coordinators and health overviews to promote fair distribution among social groups”. Int J Health Policy Manag. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.96

Huse O, Hettiarachchi J, Gearon E, Nichols M, Allender S, Peeters A (2018) Obesity in Australia. Obes Res Clin Pract 12:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2017.10.002

Khayatzadeh-Mahani A, Ruckert A, Labonté R (2018) Obesity prevention: co-framing for intersectoral ‘buy-in’. Crit Public Health 28:4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2017.1282604

Kingdon J (2011) Agendas, alternatives and public policies, 2nd edn. Longman, Boston

Knai C, Petticrew M, Mays N, Capewell S, Cassidy R, Cummins S, Eastmure E, Fafard P, Hawkins B, Jensen JD, Katikireddi SV, Mwatsama M, Orford J, Weishaar H (2018) Systems thinking as a framework for analyzing commercial determinants of health. Milbank Q 96:472–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12339

Lawless A, Baum F, Delany-Crowe T, MacDougall C, Williams C, McDermott D, van Eyk H (2018) Developing a framework for a program theory-based approach to evaluating policy processes and outcomes: Health in All Policies in South Australia. Int J Health Policy Manag 7(6):510–521. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.121

Leppo K (2008) Health in All Policies: perspectives from Europe. Public Health Bull S Aust 5:6–8

McCann W (2012) Review of non-hospital based services: a Report by Warren McCann, Internal Consultant, Office of Public Employment and Review to the Hon John Hill MP, Minister for Health and Ageing. Office of Public Employment and Review, Government of South Australia, Adelaide

McKee M, Stuckler D (2016) Current models of investor state dispute settlement are bad for health: the European Union could offer an alternative comment on “The Trans-Pacific Partnership: Is it everything we feared for health?”. Int J Health Policy Manag 6:177–179. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2016.116

Newman L, Ludford I, Williams C, Herriot M (2014) Applying Health in All Policies to obesity in South Australia. Health Promot Int. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau064

Norman J, Kelly B, Boyland E, McMahon A-T (2016) The impact of marketing and advertising on food behaviours: evaluating the evidence for a causal relationship. Curr Nutr Rep 5:139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-016-0166-6

Otero G (2018) The neoliberal diet: healthy profits, unhealthy people. University of Texas Press, Austin

Roberto CA, Swinburn B, Hawkes C, Huang TTK, Costa SA, Ashe M, Zwicker L, Cawley JH, Brownell KD (2015) Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet 385:2400–2409. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61744-X

Rodgers A, Woodward A, Swinburn B, Dietz WH (2018) Prevalence trends tell us what did not precipitate the US obesity epidemic. Lancet Public Health 3:e162–e163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30021-5

Rodriguez L, George JR, McDonald B (2017) An inconvenient truth: why evidence-based policies on obesity are failing Māori, Pasifika and the Anglo working class. Kōtuitui N Z J Soc Sci Online 12:192–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083x.2017.1363059

Rushton S, Williams OD (2012) Frames, paradigms and power: global health policy-making under neoliberalism. Global Soc 26:147–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2012.656266

South Australian Nutrition Network (2018) Select Committee into the Obesity Epidemic in Australia, Submission 98

Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F (1999) Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 29:563–570. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1999.0585

Townshend T, Lake A (2017) Obesogenic environments: current evidence of the built and food environments. Perspect Public Health 137:38–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913916679860

UK Government Office for Science (2007) Tackling obesities: future choices—modelling future trends in obesity and their impact on health. Foresight Programme, Government Office for Science, London

van Eyk H, Harris E, Baum F, Delany-Crowe T, Lawless A, MacDougall C (2017) Health in All Policies in South Australia—did it promote and enact an equity perspective? Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(11):1288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111288

Williams C, Galicki C (2017) Health in All Policies in South Australia: lessons from 10 years of practice. In: Lin V, Kickbusch I (eds) Progressing the sustainable development goals through Health in All Policies: case studies from around the world. Government of South Australia and World Health Organization, Adelaide, pp 25–42

World Health Organization (2015) 68th World Health Assembly: Contributing to social and economic development: sustainable action across sectors to improve health and health equity (follow-up of the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion) (A68/17)—Annexe: Draft framework for country action across sectors for health and health equity

World Health Organization (2017) Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Health Promot Int 32:7–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw103

World Health Organization (2018) Obesity and overweight. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed 16 Oct 2018

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the input of all Chief and Associate Investigators who have contributed to the design of this research: Angela Lawless, Colin MacDougall, Jennie Popay, Elizabeth Harris, Dennis McDermott, Danny Broderick, Ilona Kickbusch, Michael Marmot, Kevin Buckett, Sandy Pitcher, Andrew Stanley, Carmel Williams and Deborah Wildgoose. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the South Australian Government. This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (Grant No. 1027561).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants

The research was conducted according to the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki and all data collection activities involving human subjects received prior approval by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (Project number 5518) and the SA Health Research Ethics Committee (Reference number HREC/12/SAH/74).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study prior to interview, including consent to record and transcribe their interview. Interviewees were also offered the opportunity to review and revise the transcripts of their interviews.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Eyk, H., Baum, F. & Delany-Crowe, T. Creating a whole-of-government approach to promoting healthy weight: What can Health in All Policies contribute?. Int J Public Health 64, 1159–1172 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01302-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01302-4