Abstract

Objectives

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), current data on diabetes are lacking, and a rise of the epidemic is feared, given the epidemiologic transition in the country. To inform public health authorities on the current status of the diabetes epidemic, we analyzed data from the Saudi Health Interview Survey (SHIS).

Methods

Saudi Health Interview Survey is a cross-sectional national multistage survey of individuals aged 15 years or older. A total of 10,735 participants completed a health questionnaire and were invited to the local health clinics for biomedical exams.

Results

1,745,532 (13.4 %) Saudis aged 15 years or older have diabetes. Among those, 57.8, 20.2, 16.6, and 5.4 % are undiagnosed, treated uncontrolled, treated controlled, and untreated, respectively. Males, older individuals, and those who were previously diagnosed with hypertension or hypercholesterolemia were more likely to be diabetic.

Conclusions

Our findings call for increased awareness of pre-diabetes, diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes in KSA. Combatting diabetes and other non-communicable diseases should be the task of the Ministry of Health and other ministries as well, to offer a comprehensive socio-cultural approach to fighting this epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From 1990 to 2010, the number of deaths attributable to type 2 diabetes doubled from 650,000 to 1.3 million worldwide (Lozano et al. 2012). Various epidemiological studies have found that the increase in diabetes prevalence is correlated with the global urbanization: a trend toward sedentary lifestyles and poor diet is becoming the norm (Stampfer et al. 2000; Key et al. 2002; WHO/FAO Expert Consultation 2003; Amuna and Zotor 2008). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has witnessed a demographic shift over the last 20 years, accompanied by behavioral changes such as an increase in caloric, fat, and carbohydrate intake with a reduction in physical activity (Al-Hazzaa et al. 2011; Ng et al. 2011). In 2010, the country had a high proportion of years lost to disability (YLDs) due to diabetes, about 8 %, compared to ischemic heart disease, with YLDs of 0.81 %.

At the population level, the Saudi Ministry of Health (SMOH) is in charge of health promotion, early detection, and disease treatment of Saudis, a free health care system.

To best utilize its human and financial resources, SMOH needs accurate and timely data to allocate the appropriate resources for treatment by disease or disability. Current national data on diabetes in KSA are non-existent, and the most recent estimates date from 2005(Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with WHO 2005).

We conducted a large household survey to collect data on health, assess the prevalence of several non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and identify their risk factors. We analyzed data from this survey to inform the SMOH on the current status of diabetes.

Methods

The Saudi Health Interview Survey (SHIS) is a national multistage survey of individuals aged 15 years or older. Households were randomly selected from a national sampling frame maintained and updated by the Census Bureau. KSA was divided into 13 regions. Each region was divided into subregions and blocks. All regions were included, and a probability proportional to size was used to randomly select subregions and blocks. Households were randomly selected from each block. A roster of household members was conducted and an adult aged 15 or older was randomly selected to be surveyed. Weight, height, and blood pressure were measured at the household by a trained professional. Omron HN286 (SN:201207-03163F) and Omron M6 Comfort (HEM-7223-E) instruments were used to measure weight and blood pressure.

The survey included questions on socio-demographic characteristics, tobacco consumption, diet, physical activity, health care utilization, different health-related behaviors, and self-reported NCDs.

We used measured weight and height to calculate body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg)/height (m2). Participants were classified into four groups: (1) underweight, BMI less than 18.5; (2) normal weight, BMI between 18.5 and 24.9; (3) overweight, BMI between 25.0 and 29.9; or (4) obese, BMI greater than or equal to 30.0. Respondents were classified as current, past, and never smoker based on self-reported data. We computed the servings of fruits and vegetables and red meats and chicken consumed per day from the detailed dietary questionnaire as the sum of the average daily consumption of fruits, fruit juices, and vegetables and red meats and chicken. We used the International Physical Activity questionnaire (Craig et al. 2003) to classify respondents into four groups of physical activity: (1) met vigorous physical activity, (2) met moderate physical activity, (3) insufficient physical activity to meet vigorous or moderate levels, and (4) no physical activity.

To assess diagnosed hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia status, respondents were asked three separate questions: “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you had: (1) high blood pressure, otherwise known as hypertension; (2) diabetes mellitus, otherwise known as diabetes, sugar diabetes, high blood glucose, or high blood sugar; (3) hypercholesterolemia, otherwise known as high or abnormal blood cholesterol?” Women diagnosed with diabetes or hypertension during pregnancy were counted as not having these conditions. Those who were diagnosed with either of these conditions were further asked if they are currently receiving any treatment for their condition. Similarly, the same type of questions was used to determine previous diagnosis of stroke, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, cardiac arrest, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, renal failure, and cancer. We considered a person to be diagnosed with a chronic condition if they reported being diagnosed with any of these conditions.

In addition, respondents who reported being diagnosed with diabetes, were asked: “What type of diabetes do you have?” and whether they are being treated via the following question: “During the past 30 days, or since your diagnosis, have you ever taken medication for this condition?”.

Respondents who completed the questionnaire were invited to local primary health care clinics to provide a blood sample for laboratory analysis. All blood samples were analyzed in a central lab at the King Fahd Medical City in Riyadh. COBAS INTEGRA400 plus was used to measure blood levels of HbA1C, or glycated hemoglobin. We followed the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for determining diabetes status (NHANES 2009). Respondents were considered to be diabetic if they met any of the following criteria: (1) measured HbA1c equals or exceeds 6.5 % (48.5 mmol/mol), or (2) measured HbA1c not equaling or exceeding 6.5 % (48.5 mmol/mol), but the respondent reported taking medications for diabetes. Hence, the subgroup diabetic includes those with measured HbA1c equal or above 6.5 % or taking medication for diabetes. Respondents were considered to have borderline diabetes if: (1) they did not report taking drugs for diabetes, and (2) their measured HbA1c blood level was between 5.7 % (35.3 mmol/mol) and less than 6.5 % (48.5 mmol/mol). Respondents were considered undiagnosed if they reported not being previously diagnosed with diabetes but their measured HbA1c was equal or above 6.5 % (48.5 mmol/mol). The classification criteria for the different categories of diabetes are detailed in Table 1. Moreover, we examined diabetes status among those who reported that they were previously diagnosed as pre-diabetic.

Statistical analysis

We used a multivariate logistic regression model to measure association between outcome variables and socio-demographic factors first. Diabetics were compared to borderline diabetics and non-diabetics; borderline diabetics were compared to non-diabetics, and undiagnosed diabetics were compared to non-diabetics. Then, we used a backward elimination multivariate logistic regression model to measure association between outcome variables and all associated factors. All factors were first included in the models. Then variables were eliminated based on a Wald Chi-square test for analysis of effect. Variables were removed one by one based on the significance level of their effect on the model, starting with the variable with the highest p > 0.5, till all variables kept had a p ≤ 0.5 in the analysis of effect. Our results are based on a national sample for adults aged 15 or older who completed the survey and went to a clinic to undergo a physical exam.

Weighting methodology

Two sets of sampling weights were generated and incorporated into the dataset for analysis. First, we created an individual sampling weight for all respondents to account for (1) the probability of selection of an eligible respondent within a household, (2) the probability of selection of the household within a stratum, and (3) the post-stratification differences in age and sex distribution between the sample and the Saudi population.

For individuals who completed the lab-based blood analysis, we computed an additional sampling weight used in analyzing data from clinic visits to account for (1) the individual sampling weight described above, (2) the probability of visiting a clinic, (3) socio-demographic, behavioral, and health differences between respondents who visited the clinic and those who did not, and (4) the post-stratification differences in age and sex distribution between the respondents who visited the clinic and the Saudi population.

We used SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for analyses and to account for the complex sampling design.

Results

Survey response and sample characteristics

Between April and June 2013, a total of 10,735 participants completed the SHIS—a response rate of 89.4 %—and were invited to the local health clinics. The remaining 1,265 completed part of the household enumeration, or all of it, but the selected adult did not complete the survey. A total of 5,590 individuals went to the local clinics and provided blood samples for analyses—a response rate of 52.1 %. The characteristics of respondents who completed the questionnaire and the laboratory exam are presented in Table 2.

Prevalence of diagnosed, measured, borderline, and undiagnosed diabetes

Overall, 1,095,776 (8.5 %) Saudis reported being diagnosed with diabetes. However, a total of 1,745,532 (13.4 %) Saudis aged 15 years or older had diabetes. This total group is the sum of measured diabetes (1,193,075, 68.4 %) and those who were currently on diabetes medication with controlled levels of HbA1c (552,457, 31.6 %). Among those that our survey identified as diabetic from blood exams, 43.6 % were undiagnosed. Moreover, 15.2 % of Saudis, or 979,953, had borderline diabetes. Characteristics of respondents with undiagnosed diabetes, diabetes, and borderline diabetes are presented in Table 3.

Type, treatment, and control of diagnosed diabetes

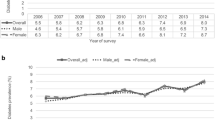

Among participants diagnosed with diabetes, 13.4 % reported being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, 66.7 % reported being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, and 19.9 % did not know their type. Also, 91.0 % reported taking medication for their condition. About 70.9 % of participants on medication for diabetes had their diabetes controlled. Hence, about 397,541 adults had uncontrolled diabetes. Among all those who are diabetic, 57.8, 20.2, 16.6, and 5.4 % were undiagnosed, treated uncontrolled, treated controlled, and untreated, respectively (Fig. 1).

Predictors of diabetes, borderline diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes

Age, sex, and diagnosis history of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia were associated with diabetes (Table 4). The risk of being diabetic was lower among females [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.68; 95 % confidence interval (CI): 0.53–0.89] but increased with age (AOR = 1.04; 95 % CI: 1.04–1.06) and previous diagnosis of hypertension (AOR = 1.82; 95 % CI: 1.31–2.53) and hypercholesterolemia (AOR = 2.18; 95 % CI: 1.51–3.15). Marital status, education, smoking status, diet, daily hours spent watching television, levels of physical activity, and history of NCDs were not associated with the risk of diabetes (Table 4). When we excluded respondents who reported being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, our results remained unchanged (data not presented). The risk of borderline diabetes was not associated with any of the socio-demographic characteristics or other risk factors studied (Table 5).

The risk of being diabetic but undiagnosed with diabetes was only associated with age (Table 6). Indeed, older individuals were less likely to be diagnosed with diabetes (AOR = 1.03; 95 % CI: 1.03–1.04).

Among Saudis aged 15 years or older, 191,957 (1.5 %) were previously diagnosed with pre-diabetes. Of those, 55.1 % were currently diabetic by our definition [measured HbA1c ≥6.5 % (48.5 mmol/mol)] or undergoing treatment for diabetes), but only 22.8 % had blood HbA1c levels ≥6.5 % (48.5 mmol/mol).

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample of Saudis aged 15 years or older, we found a high prevalence of diabetes (13.4 %). A large proportion (43.6 %) of diabetic individuals were undiagnosed, and 29.1 % of those receiving treatment had uncontrolled diabetes. An additional 15.2 % were borderline diabetic. These numbers are alarming as they indicate a total of 1,745,532 diabetic and 979,953 borderline diabetic Saudis. The KSA population is a very young population, with 80 % of the population under the age of 40 in 2013 (Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 2013), and the burden of type 2 diabetes is likely to overwhelm the health system of the country in the near future. Our results call for a national program to prevent and control diabetes. Moreover, screening campaigns are needed to detect borderline and undiagnosed diabetes at early stages for proper preventive measures and treatment.

Diabetes has a major impact on health and quality of life and is a worsening problem in both the developed and the developing world due to the complications it generates, such as heart disease, kidney disease, eye damage, neuropathy, and many others (Alberti and Zimmet 1998; Ceriello 2006). These cause an increased number of years lived with disability, during which patients suffer greatly, and increasingly, from these associated complications (Stewart and Liolitsa 1999; Egede 2004; Kalyani et al. 2010). In our study, diabetes was associated with self-reported hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. It was also associated with these diseases as measured in our survey (results not shown). These results demonstrate the joint occurrence of these three diseases, and hence a higher burden carried by Saudi patients. Moreover, Saudis treated for hypercholesterolemia were more likely to be diabetic but undiagnosed (results not shown). As hypercholesterolemia is a risk factor for diabetes, this suggests many missed opportunities within the health care system where patients with diagnosed hypercholesterolemia are not evaluated for diabetes as well.

Indeed, diabetes is preventable through a healthy lifestyle and early detection (Harris and Eastman 2000; Goldberg 2006; Lindström et al. 2006). However, Saudis do not seem to use medical preventive services, despite the fact that they are covered by a free national health system (Clark 2011). Our findings showed that only 14.8 % reported visiting a health clinic for a regular checkup within the last year (results not shown). This finding is of concern, as we found that most pre-diabetic individuals who progressed to become diabetic were able to control their diabetes once they started treatment. In a country such as KSA where medical care is free, the lack of health services utilization should be addressed through awareness campaigns. Moreover, Saudis are engaged in behavioral activities that are contributing to the high rates of diabetes and borderline diabetes. For example, our survey shows low levels of fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity.

Diabetes has major economic impact, including loss in human capital, decrease in productivity, and medical costs (American Diabetes Association 2013; WHO 2014; Ng et al. 2014). The medical costs not only arise from the direct cost of treatments for high glucose levels but extend to include the treatment costs of diabetes complications. In the United States, one in five health care dollars is spent on diabetes (American Diabetes Association 2013).

Previous studies have reported on the prevalence of diabetes in KSA. Data from the 1980s showed a prevalence of 4.7 % among Saudis aged 15 years or older in rural Saudi Arabia (Fatani et al. 1987). A study conducted from 1995 to 2000 revealed a 23.7 % prevalence of type 2 diabetes among individuals 30–70 years old (Al-Nozha et al. 2004). The last reported prevalence of diagnosed and measured diabetes in KSA was in 2005, which revealed a 15.3 % prevalence of diagnosed diabetes and an 18.3 % prevalence of measured diabetes [HbA1c greater or equal to 7.0 % (53 mmol/mol)] among Saudis aged 15–64 years (Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with WHO 2005). When restricted to the same age groups and using the same cutoff point, our data revealed a prevalence of 7.1 and 5.4 % for these categories, respectively. However, the two surveys cannot be compared. In our survey, we applied post-stratification weights to reflect the Saudi population and adjusted for the increased probability of sick individuals to agree to visit health facilities for physical examinations and blood samples. As these steps were not taken in the previous survey, the prevalence of diabetes and other NCDs may have been overestimated. Indeed, when we did not apply adjustments based on post-stratification and the predicted probability of completing the clinic visit, our diagnosed and measured diabetes estimates were 8.9 % (95 % CI: 8.3–9.4) and 10.3 % (95 % CI: 9.3–11.3), respectively. In our survey, 50 % of participants went to a clinic for physical measurements. When we compared the two groups, those who went to a clinic were more likely to self-rate their health as good, fair, or poor, be overweight or obese, and to have received a diagnosis of pre-diabetes. They were less likely to smoke and to have had their last routine physical exam prior to 2012. Hence, our adjustment for the predicted probability of completing the clinic visit was critical to produce nationally representative estimates of diabetes. Both our survey and the 2005 report were conducted by medical staff from local health facilities. It is possible that sick individuals were more likely to participate in the 2005 survey. However, in our study, we enforced a random selection within a household, and our electronic data capture registered the selected individual and would not allow for a replacement.

Over the last few years, the SMOH started several initiatives to control chronic diseases and the diabetes epidemic, including a national awareness program around diabetes (Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 2014). These initiatives could have resulted in some decline in diabetes prevalence over the last eight years. Also, in September 2012, the SMOH in collaboration with the World Health Organization’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) organized an international conference that aimed to address the topic of NCDs in the area (WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean 2012). The conference resulted in the Riyadh Declaration that included ten recommendations to combat NCDs at the regional level (WHO EMRO 2012). The SMOH worked with EMRO, and the declaration was adopted by EMRO during the regional committee meeting in October 2012. This step will amount to a major impact on health in KSA and the region. Indeed, the Gulf countries have similar habits and health profile (Mokdad et al. 2014). Hence our findings could be used by the gulf countries and the gulf council to promote health, control and treat diabetes in the region (Secretariat General 2012). More so, inter-countries collaboration, especially through the developed–developing countries model, can be beneficial to KSA and the region in their fight against NCDs (Maziak et al. 2013).

Our study has some limitations. First, our data are from a cross-sectional study, and therefore, we cannot assess causality. Second, many of our behavioral data, such as diet and physical activity, are self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability biases. However, our study is based on a large sample and used a standardized methodology for all its measures. Third, only 52 % of respondents completed the visit to a health clinic and had their blood drawn for analysis. However, our weighting methodology accounted for this bias by applying a post-stratification adjustment using socio-demographic characteristics, health behaviors, previously diagnosed NCDs, and anthropometric measurements of respondents from the household survey.

Our study revealed a high rate of diabetes in a young population in KSA. The country, however, is not alone in this epidemic. In 2010, diabetes ranked the fifth cause of death in the Arab World, an increase from the 11th cause as reported for 1990(Mokdad et al. 2014). Moreover, our findings of the low utilization of free health services for preventive care call for a major effort to inform the public of the value of prevention. In addition to regular physical checkups and screenings, programs to improve diet and increase physical activity are urgently needed. These programs should take into account the culture and environment in KSA. Creative methods will need to be adopted to increase physical activity in a very hot environment. In many places in the world, outdoor activities are encouraged, but in KSA indoor activities have to be established and made available to the public and communities, perhaps using the KSA’s large indoor infrastructure including malls and public spaces.

Our findings call for increased awareness of diabetes and undiagnosed diabetes in the Kingdom. Moreover, our study calls for an improvement in the early detection of pre-diabetes, as it is the first step in prevention, especially among adults 35 years and older. The detection campaigns should be coupled with intensive and aggressive programs for prevention and control of diabetes. A national chronic disease program should be established and involve several partners. Indeed, to combat NCDs, a large segment of the government and society has to be involved. This is not a task for the Ministry of Health alone, but requires involvement of other ministries to offer a comprehensive socio-cultural approach to fighting this epidemic.

References

Alberti Kgmm, Zimmet Pz (1998) Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO Consultation. Diabet Med 15:539–553. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539:AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S

Al-Hazzaa HM, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI et al (2011) Physical activity, sedentary behaviors and dietary habits among Saudi adolescents relative to age, gender and region. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8:140. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-140

Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY et al (2004) Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 25:1603–1610

American Diabetes Association (2013) Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 36:1033–1046. doi:10.2337/dc12-2625

Amuna P, Zotor FB (2008) Epidemiological and nutrition transition in developing countries: impact on human health and development. Proc Nutr Soc 67:82–90. doi:10.1017/S0029665108006058

Ceriello PA (2006) Oxidative stress and diabetes associated complications. Endocr Pract 12:60–62. doi:10.4158/EP.12.S1.60

Clark M (2011) Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediterr Health J 17:784–793

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M et al (2003) International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35:1381–1395. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

Egede LE (2004) Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among U.S adults. Diabetes Care 27:421–428. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.2.421

Fatani HH, Mira SA, El-Zubier AG (1987) prevalence of diabetes mellitus in rural Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Care 10:180–183. doi:10.2337/diacare.10.2.180

Goldberg RB (2006) Lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes. Lancet 368:1634–1636. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69676-1

Harris MI, Eastman RC (2000) Early detection of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus: a US perspective. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 16:230–236. doi:10.1002/1520-7560(2000)9999:9999<:AID-DMRR122>3.0.CO;2-W

Kalyani RR, Saudek CD, Brancati FL, Selvin E (2010) Association of diabetes, comorbidities, and A1C with functional disability in older adults results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2006. Diabetes Care 33:1055–1060. doi:10.2337/dc09-1597

Key TJ, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC (2002) The effect of diet on risk of cancer. Lancet 360:861–868. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09958-0

Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M et al (2006) Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 368:1673–1679. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al (2012) Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380:2095–2128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0

Maziak W, Critchley J, Zaman S et al (2013) Mediterranean studies of cardiovascular disease and hyperglycemia: analytical modeling of population socio-economic transitions (MedCHAMPS)—rationale and methods. Int J Public Health 58:547–553. doi:10.1007/s00038-012-0423-4

Ministry of Health (2005) Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with WHO (2005) Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in collaboration with, World Health Organization. EMRO, Country-Specific standard report Saudi Arabia

Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2013) Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Projected Population 2013

Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2014) National Program for Diabetes Awareness. http://sahsehlo.moh.gov.sa/Pages/Home.aspx

Mokdad AH, Jaber S, Aziz MIA et al (2014) The state of health in the Arab world, 1990–2010: an analysis of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. Lancet 383:309–320. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62189-3

Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Ali HI et al (2011) The prevalence and trends of overweight, obesity and nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in the Arabian Gulf States. Obes Rev Off J Int Assoc Study Obes 12:1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00750.x

Ng CS, Lee JYC, Toh MP, Ko Y (2014) Cost-of-illness studies of diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2014.03.020

NHANES (2009) National Heatlth and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Health Tech/Blodd Pressure Procedures Manual. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Secretariat General (2012) The Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf. http://www.gcc-sg.org/eng/

Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE et al (2000) Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med 343:16–22. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007063430103

Stewart R, Liolitsa D (1999) Type 2 diabetes mellitus, cognitive impairment and dementia. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc 16:93–112

WHO EMRO (2012) International Conference on healthy Lifestyles and noncomunicable diseases in the arab world and the middle east. The Riyadh Declaration

WHO (2014) WHO Diabetes: the cost of diabetes. In: WHO. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs236/en/. Accessed 22 May 2014

WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2012) International conference on healthy lifestyles and noncommunicable diseases in the Arab world and the Middle East, Riyadh, 10–12 September 2012. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003) Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 916:i–viii, 1–149, backcover

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

El Bcheraoui, C., Basulaiman, M., Tuffaha, M. et al. Status of the diabetes epidemic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Int J Public Health 59, 1011–1021 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0612-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-014-0612-4