Abstract

Water quality degradation is one of the largest threats to freshwater ecosystems. Nutrient inputs, land use changes, and climate are expected to be the most important drivers of water quality degradation. Here, we quantify the relative influence of nutrient inputs, climate, and lake geomorphometry on primary production in freshwater lakes globally, using chlorophyll a (chla) as a proxy. We used a large lake chlorophyll database that included chla and total phosphorus, in addition to lake geomorphometric variables (mean depth, watershed area, elevation, surface area, volume, residence time) and climate (air temperature, precipitation, cloud cover, solar radiation) for 2561 freshwater lakes around the globe. Our model was able to explain 60% of the variation in chla concentrations. Of that, total phosphorus (TP) explained 42%, a combination of climate variables explained 38%, and geomorphometrics explained 20% of the variation. Although there have been increased efforts and regulations in place for land use and farming, nutrient inputs continue to be the leading cause of primary production in lakes. However, the influence of climatic variables acting synergistically (temperature, precipitation, cloud cover and solar radiation) is nearly equal to that of total phosphorus, suggesting nutrient management efforts are not sufficient alone to mitigate water quality degradation. Our findings underscore the critical need to incorporate climate factors into water quality management given current climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eutrophication is one of the most prevalent threats to freshwater resources, with consequences for public health, food security, biodiversity and other ecosystem services, highlighting the urgency of understanding controls on water quality. Nutrients, particularly total phosphorus, have long been recognized as a primary factor influencing water quality (Quinlan et al. 2020; Schindler 1997). Hydrology and climate are tightly coupled, and climate change is affecting water quality through warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns which can increase in nutrient inputs from land (Michalak 2016). For example, regions that are experiencing increases in precipitation are likely to see a rise in eutrophication driven by increases in nutrient runoff (Sinha et al. 2017). These increases in algal biomass have further implications for greenhouse gas sources (Beaulieu et al. 2019) and sinks (Webb et al. 2019), as well as for the presence of cyanobacterial toxins (Hayes and Vanni 2018). Understanding how climate drivers interact with nutrients to impact water quality is important for environmental management and improving water quality can subsequently mitigate the consequences of climate change on aquatic ecosystems (Vaughan et al. 2019).

Climate is increasingly being recognized as an important driver of water quality at local to regional scales. Synchronous changes in lake algal biomass associated with climate-mediated variability in the hydrological cycle suggests that climate plays an important role in chlorophyll a (chla) dynamics (Baines et al. 2000). In general, increases in nutrient loading from greater precipitation exacerbate water quality problems through increases in chla, changes in phytoplankton community composition (Jeppesen et al. 2009), and decreases in water clarity (Rose et al. 2017). In the northeastern United States, summer air temperatures and winter precipitation were significant predictors of summer algal biomass (Collins et al. 2019). Temperature has been associated with increased chla in other regional studies (Woelmer et al. 2016). The dominance of cyanobacteria, which may generate harmful algal blooms (HABs), increases at warmer temperatures despite no changes to nutrient levels or total nitrogen: total phosphorus ratios (McQueen and Lean 1987). Warmer air temperatures contribute to earlier ice-out, leading to a longer growing season and higher chla levels (Preston et al. 2016), and changes in the onset and strength of thermal stratification can lead to increases (e.g. Jöhnk et al. 2008) or decreases in algal biomass (e.g. Verburg and Hecky 2003). Additionally, while temperature is generally positively correlated with algal biomass, the response can vary depending on lake trophic status, trophic interactions, and resource availability (Kraemer et al. 2017).

Solar radiation is important for primary production, and recent changes in solar radiation at earth’s surface have the potential to influence chla. Broadly, the earth’s surface underwent a period of declining solar radiation from around 1950 until the mid-1980s, referred to as ‘global dimming’, after which solar radiation increased and stabilized (Wild et al. 2005; Sanchez-Lorenzo et al. 2015), creating a recent period of ‘global brightening’ (Wild et al. 2015). These large-scale changes have been attributed to changes in the transparency of the atmosphere owing to anthropogenic aerosol emissions and/or cloudiness (Gan et al. 2014; Long et al. 2009; Mateos et al. 2014). Recent trends in brightening are most apparent in regions that have long been industrialized, whereas newly industrialized regions have seen continued dimming (Wild 2012). For example, from 1980 to 2010 in Europe and North America, average surface solar radiation increased up to 8 W m−2 per decade (Wild 2012). In contrast, surface solar radiation decreased by up to 10 W m−2 per decade in India (Wild 2012). Patterns in solar radiation brightening and dimming vary spatially (e.g. Wild et al. 2012) and temporally (e.g. Sanchez-Lorenzo et al. 2015). For example, there may be increases in solar radiation in one season but decreases in another (Deng et al. 2019; Sanchez-Lorenzo et al. 2015). Long term trends can be substantially greater than that of the 11-year solar sunspot cycle, which varies only by approximately 1 W m−2 and is known to have a wide range of effects (Engels and van Geel 2012). Declines in solar radiation are associated with similar reductions in PAR, contributing to “underwater darkening” and decreases in Secchi depth across lakes (Zhang et al. 2020), and have the potential to influence algal growth and biomass as well as other components of lake ecosystems.

Lake basin morphology and hydrology have the capacity to influence water quality, particularly with respect to interactions with other drivers. Factors such as lake depth and surface area influence physical, chemical, and biological processes within the lake, with consequences for mixing regimes, nutrient availability, and residence times. Deeper lakes typically have both lower total phosphorus (TP) and lower chla concentrations (Canfield et al. 2016; Fergus et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2012). For example, deeper lakes had clearer water in Wisconsin, although this only occurred in watersheds with low levels of agriculture (Rose et al. 2017). Lake surface area has also been identified as an important contributor to chla (Woelmer et al. 2016). Among deeper lakes in eastern China, those with a smaller surface area had higher chla concentrations compared to larger lakes (Huang et al. 2014). Longer residence times have been associated with lower chla concentrations in Europe (Noges 2009), but with higher concentrations in eastern China (Liu et al. 2012). However, none of these previous studies have comprehensively considered lake geomorphometric and hydrologic characteristics in the context of both climate and nutrient factors.

Current trajectories in climate, the continuing influence of nutrient management legacies (Sharpley et al. 2013), and the growing demand for clean freshwater underscore the importance of understanding drivers of water quality. Patterns in water quality can be highly variable, driven by many factors that operate at different spatial scales (Fergus et al. 2016). Nutrient concentrations, particularly phosphorus, are well-established as key predictors of chla (Prairie et al. 1989; McCauley et al. 1989; Abell et al. 2012; Quinlan et al. 2020), but macro-scale analyses have focused primarily on temperature and precipitation, while also excluding many geomorphometric variables (e.g. Collins et al. 2019). Additionally, previous studies have not included potentially important climate factors, such as solar radiation (Wild 2012) and other variables that can influence solar radiation at more local scales (e.g. cloudiness). Essentially, the full suite of climate and lake geomorphic variables has not been incorporated into studies of lake chla across a wide range of lake conditions.

We used a large lake chla database from 2561 lakes in 7 countries to explore how nutrient, climate, and geomorphic factors influence water quality. Using a similar dataset, Quinlin et al. (2020) had used a single-predictor model incorporating co-variation of additional predictors, but here we formally partition that variation. Such large macroscale ecological studies pose challenges such as the incorporation of interactions across scales (Soranno et al. 2010; Heffernan et al. 2014), diverse data objects (Heffernan et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2014), and varied data-intensive approaches (Levy et al. 2014), yet can reveal interactions among scales that are important features of ecological systems (Peters et al. 2007; Soranno et al. 2010). In this study we asked, in addition to total phosphorus, which climatic and lake geomorphometric factors influence water quality? We used this lake chla dataset with a more complete set of climate variables to examine the relative importance of nutrient inputs, climate conditions, and lake morphology factors on chla concentrations for lakes worldwide. We explored the relative roles of temperature, solar radiation, cloud cover, and precipitation, at various seasonal scales as well as a wide range of geomorphic factors (depth, residence time, volume, surface area, elevation, and watershed area).

Methods

Data acquisition and dataset compilation

Assembling large-scale data into one unified dataset can be challenging because of the various thematic datasets (e.g., hydrological, geological, morphological, meteorological), data sources (e.g., in situ sampling, remote sensing, laboratory processed), and the various jurisdictions the data was collected from which had their own protocols, measurement techniques, and research purposes (Soranno et al. 2010; Heffernan et al. 2014; Levy et al. 2014). Further, the datasets may contain corrupted, missing, or meaningless data which makes it difficult to extract the required results and reduces the power of the models (Kelling et al. 2009; Michener and Jones 2012; Levy et al. 2014). Data consistency and completeness is an important part of the qa/qc process to reduce data gaps and noise. However, once the data is prepared, data-driven models can allow for large amounts of knowledge to be extracted while minimizing the cost and time as well as maximizing the accuracy, speed, reliability, and comprehensibility of the models produced (Vargas et al. 2011).

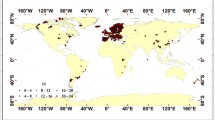

From a large lake chla database that included total phosphorus (Filazzola et al. 2020), we used 2561 lakes for which we were also able to acquire climate and solar radiation data (Fig. 1; Table S1). Although the distribution of the lakes is heavily biased towards North America, our dataset contained a wide range for all variables, with an average of three orders of magnitude for water quality and geomorphic factors (range 2–6 orders of magnitude; Table S1). Each chla measurement corresponded with the year in which the measurement was taken and the lake’s latitude and longitude. In instances where the same lake was sampled in multiple locations, we took the median values of measured data for that lake. When a lake was sampled multiple times within the same year (e.g. monthly), we extracted data from the time when chla values were greatest. If a lake was sampled over multiple years, we selected data from the most recent year because it most closely resembles the most recent status of that lake. TP and climate data were collected in the same manner and matched with corresponding chla values. The Laurentian Great Lakes were also excluded because of significant spatial heterogeneity in water quality due to their size. While this dataset includes samples collected with a variety of methodologies, we do not anticipate that the international multi-jurisdictional nature of the data will influence analyses, as Hanna and Peters (1991) showed that differences in protocol and sampling depth for TP and chla did not add variation to TP-chla response models (Filazzola et al. 2020; Quinlan et al. 2020). If lake geomorphometrics were not included in the dataset, we extracted them from HydroLAKES (Messager et al. 2016). HydroLAKES provides the shoreline polygons of all global lakes with a surface area of at least 10 ha, as well as estimates of the shoreline length, average depth, water volume and residence time (Messager et al. 2016). The unique IDs in the lake chla dataset match those in HydroLAKES for this purpose. (Fig. S3; Supplementary Information Table 1).

For climate variables, we extracted air temperature (°C), precipitation (mm), cloud cover (%) for each lake and sampling year from the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit (CRU) online open access database (Harris et al. 2020). CRU interpolates air temperature and precipitation from meteorological station measurements and summarizes the database on a grid at a 0.5° latitude and longitude resolution. Shortwave incoming solar radiation in the near infrared (0.2–4 μm) data was collected from CLARA A-1 which is gridded at a 0.25 × 0.25 degrees resolution between 1982 and 2009 (Karlsson et al. 2013). Using the monthly mean temperature, precipitation, cloud cover and solar radiation values, we calculated the mean, maximum, and standard deviation annually, for each season, and at a lag of 1 year. For the scope of our study we used spring (March, April, May for the Northern Hemisphere, and September, October, November for the Southern Hemisphere) and summer (June, July, August for the Northern Hemisphere, and December, January, February for the Southern Hemisphere) climate variables because that is when algal biomass is the most abundant.

Data analyses

Chlorophyll a was tested against total phosphorus (TP), climate (solar radiation, summer and spring air temperature, precipitation, and cloud cover) and geomorphometry (lake mean depth, elevation, area, residence time, total volume, and watershed area). We assessed normality of all variables using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and a qqplot using the “ks.test” and “qqnorm” functions in R. The primary variables of interest (chla and TP) were log10 transformed before applying the randomforest function (package = randomforest) with iteration = 5 (Liaw and Wiener 2002). Kendall’s Tau correlation coefficients were calculated between all variables using the “cor” function in R.

We used (i) random forests; (ii) linear models; and (iii) principal component analysis to evaluate the relationships between chla and nutrient, climatic, and geomorphometric factors. The random forest was used because it is a powerful explanatory analysis and helped us identify the most influential predictor variables. We then used linear models to gauge how strong the relationship between chla and its strongest drivers were. The PCA was finally used to identify synergies between predictor variables, which was something not evident from the random forest or linear models. The three analyses each provide novel insights which better elucidate the relationship between chla and its drivers, however, the three models also drew similar conclusions, which suggests the results were robust.

First, we conducted a random forest analysis to identify the nutrient, climatic, and geomorphometric factors that influence chla at a statistically significant threshold. Decision trees are the basic building blocks for a random forest. The decision tree is a machine learning algorithm which fits complex datasets with interacting predictor variables (Ali et al. 2012; Ben-Haim and Tom-Tov 2010). Random forest analyses are classified as a strong learner because they are built as an ensemble of decision trees (Ali et al. 2012; Breiman 2001). Random forest analyses work through bagging or bootstrap aggregation where subsets of the training data are randomly sampled, and a model is fit to these smaller data sets after which the predictions are aggregated (Ali et al. 2012; Breiman 1996, 2001). For our analysis we conducted 5 iterations consisting of 500 trees and proximity = TRUE as a similarity measure which accounts for the number of times certain variables end up on the same node. Cross validation is not required because bootstrap sampling excludes data that was not used in the model and creates an out of bag error (oob). This prevents overfitting in the random forest model.

We then investigated the relationship between chla and TP, and the climate variables mentioned previously. The linear regression models the relationship between the predictor and response variables by fitting a linear equation (Y = Xβ + ε) to observed data (Bhattacharya and Burman 2016). We report linear regression results here because linearity checks showed that the only relationship which exhibited non-linearity was chla-TP, and generalized additive models (GAMs) showed similar results to the linear models. To test the variables influencing chla, we fitted linear regression models (function: lm) with chla as the response variable and the climate, nutrient, and lake morphometric variables as the predictors. We ran separate models for each of the predictors. Finally, we also calculated the Akaike information criterion (AIC) values for each corresponding model, where a lower AIC score is indicative of the most parsimonious model.

Finally, we conducted a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) in R (function prcomp) to summarize the relationships between chla, climate, and nutrient levels with a reduced number of dimensions. The previous two models showed which predictor variables influence algal growth in lakes and how strongly they influence it; however, the PCA emphasizes major directions in variation and helps identify the relation between predictor variables and how they may have combined effects on algal growth in lakes. The PCA is an algorithm that generates principal components (ordination axes) along which the data show the maximum amount of variation. One of the outputs of a PCA is a two-dimensional ordination plot which can allow for the visualization of relationships among predictor variables and among individual observations (Legendre and Legendre 2012). We did not include the geomorphometric variables because there were missing data and we did not want to comprise our sample size, which would have been reduced by 37%. Further, we wanted to focus more so on the impacts climate and nutrients have on lake primary production, as these were the major factors explaining variation overall. We generated the PCA visual using the ‘fviz_pca_var()’ function from the package = factoextra.

Results

The random forest analysis using nutrient concentrations, climatic variables, and lake geomorphometric characteristics as predictors explained 60% of variation in lake chla levels. The random forest regression had a mean of squared residual of 0.12 suggesting that the model is a good fit (Fig. 2). Total phosphorus was the most important factor influencing lake chla concentrations, explaining approximately 42% of the variation that was explained (Fig. 2). Other climatic variables, comprising summer and spring air temperatures, solar radiation, precipitation, and cloud cover cumulatively explained 38% of the total variation that was explained (Fig. 2). Notably, the most influential climatic variables were summer and spring air temperature, but spring solar radiation was the next most influential climate variable—even more so than precipitation and cloud cover. Geomorphometric characteristics accounted for the least amount of variation in chla and contributed to 20% of the total variation that was explained, with lake watershed area being the most important (Fig. 2).

Stacked bar plot representing the proportion of variation in chla explained by each variable in the random forest model. Variables are separated into groups characterized by nutrients (total phosphorus), climate (spring and summer solar radiation, cloud cover, precipitation, and air temperature), and morphology (elevation, lake area, mean depth, residence time, volume, watershed area)

The linear models supported the results from the random forest (Fig. 3). The TP-chla relationship was best explained by a linear model (P < 0.001, R2adj = 0.47, AIC = 6581.4) which suggests a fairly strong model fit and a significant positive relationship (Fig. 3). The linear models also supported the influential role of solar radiation (P < 0.001, R2adj = 0.041, AIC = 8367.04) (Fig. 3), summer air temperature (P < 0.001, R2adj = 0.14, AIC = 8085.00), and summer precipitation (P < 0.001, R2adj = 0.019, AIC = 8425.50) as positive correlates of chla. Conversely, summer cloud cover (P < 0.001, R2adj = 0.045, AIC = 8356.17) was negatively associated with chla.

The first two axes of the PCA explained 53.7% of the variation, with principal axis one explaining 33.8% and principal axis two explaining 19.9% of the variation (Fig. 4). Chlorophyll a was closely associated with spring and summer temperature, TP, and also associated with spring solar radiation (Fig. 4 and S1).

The most variation was explained by Principal Component 1 (Dim1), followed by the second principal component axis (Dim2). The arrows depict the environmental variables considered in the analysis. The longer the arrow, the more influential the variable. The angle between arrows suggests the correlation between variables. The acronyms are as follows: TP (total phosphorus), Temp (temperature), Ppt (precipitation), Srad (solar radiation), Cldcvr (cloud cover). TP, spring and summer temperature, and spring Srad are closely aligned with chla, and summer Srad is more distantly aligned with chla. Spring and summer cloud cover are orthogonal to chla

Discussion

Our study examined chla concentrations across a large gradient of lakes to identify the most influential factors associated with algal biomass and attempted to understand how these potential drivers may synergistically influence the abundance of lake algae. Our models confirmed that total phosphorus (TP) was the most influential driver of chla concentrations, yet, the combined impact of climate variables (temperature, solar radiation, precipitation, and cloud cover) was equally as important. In particular, solar radiation had a critical influence on summer chla when incorporated into our models (see Supplementary Information for the models without solar radiation for comparison). Lake geomorphometric characteristics also explained some variation in our models, but to a much lesser extent when compared to TP and climate variables.

Our results underscore the role of total phosphorus as a primary predictor of chla in freshwater lakes even when analyses are global in scale, maximizing climate gradients. We found that TP explained approximately 40% of the variation in chla concentrations. Total phosphorus has been well established as a predictor of chla, including at large scales (Abell et al. 2012; McCauley et al. 1989; Prairie et al. 1989; Quinlan et al. 2020). Freshwater ecosystems naturally act as nutrient sinks, as well as receive phosphorus inputs from a number of human activities (e.g. excess P-fertilizer use (Carpenter 2005), P-containing pesticides (Arbuckle and Downing 2001), and domestic and industrial sewage (Smith and Schindler 2009). Our results showing that the correlation between TP and chla concentration was moderate (⍴ = 0.5; Fig. S1) and that TP explained approximately 40% of the variation in chla concentrations are consistent with previous examinations of the TP-chla relationship at global scales (Abell et al. 2012; Quinlan et al. 2020). Across a large gradient of phosphorus concentrations, the TP-chla relationship is sigmoidal, structured by breakpoints related to limitation by nitrogen among other factors (Quinlan et al. 2020). Variation within the global TP-chla relationship is large and the nature of the relationship varies among regions (Filstrup et al. 2014; Quinlan et al. 2020). This variation is postulated to be due to a wide array of factors in addition to nitrogen limitation both when phosphorus is very high (e.g. Filstrup and Downing 2017) and very low (e.g. Morris and Lewis 1988), as well as watershed land use (Filstrup et al. 2014). For example, the accumulation of algal biomass could be limited by cold water temperatures (Butterwick et al. 2005) or shading from dense algal blooms (Agustí et al. 1990). Alternatively, algal biomass could be greater than expected due to a combination of lake depth and transparency allowing for specific species to thrive (Hennemann and Petrucio 2016).

In addition to exploring the chla-TP relationship, we were able to examine the importance of climate variables for predicting chla levels. The combination of climate variables considered in our study explained as much variation as TP in global chla concentrations. For example, past studies have suggested that chla concentrations were lower in regions with less surface level solar radiation (Zhang et al. 2020). Light limitation of algal growth has been demonstrated in many lakes by experiments (e.g. Dubourg et al. 2015) and can vary by season (e.g. Kolzau et al. 2014). For example, in western Lake Erie, solar radiation was a top predictor of chla concentrations in spring and summer compared to other climate and nutrient factors, explaining 38 and 25% of the total variation respectively each season (Tian et al. 2017). Increases in winter and spring solar radiation over the past two decades were drivers of phytoplankton abundance and composition in those seasons in Lake Taihu (Deng et al. 2019). Increases in solar radiation have also been linked to warming of lake water temperatures around the globe (O’Reilly et al. 2015; Schmid and Köster 2016; Zhong et al. 2016). We observed strong correlations between solar radiation and air temperature across a wide range of lakes (Fig. S1). Solar radiation contributes to lake heat budgets and water temperatures (Schmid et al. 2014), thus our lake temperatures were also likely warmer with greater solar radiation. Warmer water temperatures increase algal growth rates and have been linked to increases in chla and algal blooms (Ho et al. 2019). Since we did not have water temperature data, we could not examine if the importance of solar radiation for predicting chla was related to water temperature, increased light availability, or both. Additionally, we were unable to explore trends in chla concentrations within lakes, which could also facilitate understanding the relative roles and interactions of these different drivers. We suggest that future studies investigate the contribution of global brightening as well as water temperature to chla trends in lakes around the world.

The ability to identify the major drivers of lake chla depends on both the suite of factors incorporated into the analyses as well as the time scales that are involved. The climate variables found to predict chla levels and their relative importance have varied significantly among studies. For example, summer and spring temperature, as well as winter precipitation, were the most important predictors of chla among lakes in the northeastern region of the United States (Collins et al. 2019). However, a similar study found that water clarity in the northeast US correlated more strongly with summer precipitation, and not with maximum air temperatures, while in the midwest there was no relationship to summer precipitation and a negative correlation with maximum air temperatures (McCullough et al. 2019). Most prior studies have been regional in scale and investigated only temperature and precipitation (e.g. Collins et al. 2019) using lag times of conditions ranging between the prior two weeks (Lennard 2019) to the previous year (Collins et al. 2019). In addition, lake trophic status can be an important consideration, as a study of 188 lakes found that the relationship between water temperature and chla was positive for eutrophic lakes, but negative for oligotrophic ones (Kraemer et al. 2017). Thus, while it is difficult to compare specific findings across studies, temperature and precipitation are consistently key overarching factors, and it is clear that lake water quality is sensitive to climate in ways that are highly variable within and across regions.

Our results showed that the relationships between chla and lake geomorphometric and hydrological factors were less important in the broader context of climate and nutrients. Although geomorphic factors (area, mean depth, and elevation) and hydrology (residence time) did play a role in determining chla, these factors were much less important than climate and total phosphorus. Lake mean depth was the most important of these factors, but in combination, morphology and residence time only contributed to about 20% of the variation in chla (Fig. 1). Mean depth and water residence time have explained a much greater proportion of the variation in other studies, but this may be because all lakes considered in those studies were relatively deep (Liu et al. 2012). Ultimately, lake depth affects the mixing regime and degree of stratification, which is probably the more proximal factor influencing the TP-chla relationship. Chlorophyll a was negatively correlated with mean depth, as has been found in other studies (Fig. 3f) (Canfield et al. 2016; Fergus et al. 2016). Shorter residence times are often associated with a flushing effect, leading to relatively lower chla concentrations (Wagner et al. 2011; Filstrup et al. 2014). Longer residence time can allow for the development of greater biomass in lakes that already have high nutrient concentrations (e.g. Huang et al. 2014) but does not appear to influence chla concentrations in lakes that have low nutrient concentrations (e.g. Nõges 2009). Overall, our results are consistent with various regional-scale studies that indicate an influence of lake morphology and hydrology on chla but highlight that these factors are relatively minor compared to climate and total phosphorus.

Conclusion

While our study underscored the importance of TP as a driver of chla concentrations, we also found that the role of climate was just as important as TP. The primary role of TP in chla has been well established, but the variation within this TP-chla relationship is large (Quinlan et al. 2020). Our results indicate that the factors contributing to this variation are primarily composed of a combination of climate and geomorphometric variables, but spring and summer climate variables also clearly emerged as important factors influencing summer chla, further highlighting their role in ecosystem structure at various spatiotemporal scales (Collins et al. 2019). Geomorphometric and hydrological features were also important but had a reduced role relative to climate in terms of explaining overall variation in summer chla. The relatively similar contributions of climate and nutrients suggest that management plans focused primarily on nutrient reductions may also need to consider the implications of ongoing climate change in order to achieve desired outcomes (Trolle et al. 2011; Paerl et al. 2016). Our study highlights the specific aspects of climate that should be taken into consideration, and fortunately future projections for these climate variables are readily available from existing climate models (Flato et al. 2013). Changes in temperature and precipitation during spring and summer seasons are occurring across many parts of the world, and these changes will clearly present challenges for management of water quality if not incorporated into water quality management frameworks.

Availability of data and material

Filazzola, A., Mahdiyna O., Shuvo, A., Ewins, C., Moslenko, L., Sadid, T., et al. 2020. A global database of chlorophyll and water chemistry in freshwater lakes. Scientific Data.

References

Abell JM, Özkundakci D, Hamilton DP, Jones JR (2012) Latitudinal variation in nutrient stoichiometry and chlorophyll-nutrient relationships in lakes: a global study. Fundam Appl Limnol 181(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1127/1863-9135/2012/0272

Agusti S, Duarte CM, Canjield DE (1990) Phytoplankton abundance in Florida lakes: evidence for the frequent lack of nutrient limitation. Limnol Oceanogr 35(1):181–187. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1990.35.1.0181

Ali J, Khan R, Ahmad N, Maqsood I (2012) Random forests and decision trees. Int J Comput Sci Issues 9(5):272–278

Arbuckle KE, Downing JA (2001) The influence of watershed land use on lake N: P in a predominantly agricultural landscape. Limnol Oceanogr 46(4):970–975. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2001.46.4.0970

Baines SB, Webster KE, Kratz TK, Carpenter SR, Magnuson JJ (2000) Synchronous behavior of temperature, calcium, and chlorophyll in lakes of northern Wisconsin. Ecology 81(3):815–825. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0815:SBOTCA]2.0.CO;2

Beaulieu JJ, DelSontro T, Downing JA (2019) Eutrophication will increase methane emissions from lakes and impoundments during the 21st century. Nat Commun 10(1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09100-5

Ben-Haim Y, Tom-Tov E (2010) A streaming parallel decision tree algorithm. J Mach Learn Res 11:849–872

Bhattacharya PK, Burman P (2016) Theory and methods of statistics. Academic Press, New York

Breiman L (1996) Bagging Predictors, URL: https://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.1007%2FBF00058655. Machine Learning, 24(421), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00058655

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45(1):5–32. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429469275-8

Butterwick C, Heaney SI, Talling JF (2005) Diversity in the influence of temperature on the growth rates of freshwater algae, and its ecological relevance. Freshw Biol 50(2):291–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2004.01317.x

Canfield DE, Bachmann RW, Stephens DB, Hoyer MV, Bacon L, Williams S et al (2016) Monitoring by citizen scientists demonstrates water clarity of Maine (USA) lakes is stable, not declining, due to cultural eutrophication. Inland Waters 6(1):11–27. https://doi.org/10.5268/IW-6.1.864

Carpenter SR (2005) Eutrophication of aquatic ecosystems: bistability and soil phosphorus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(29):10002–10005. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0503959102

Collins SM, Yuan S, Tan PN, Oliver SK, Lapierre JF, Cheruvelil KS et al (2019) Winter precipitation and summer temperature predict lake water quality at macroscales. Water Resour Res 55(4):2708–2721. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018WR023088

Deng C, Tong Y, Chen L, Yuan W, Sun Y, Li J et al (2019) Impact of particle chemical composition and water content on the photolytic reduction of particle-bound mercury. Atmos Environ 200:24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.11.054

Dubourg P, North RL, Hunter K, Vandergucht DM, Abirhire O, Silsbe GM et al (2015) Light and nutrient co-limitation of phytoplankton communities in a large reservoir: Lake Diefenbaker, Saskatchewan, Canada. J Great Lakes Res 41:129–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2015.10.001

Engels S, van Geel B (2012) The effects of changing solar activity on climate: contributions from palaeoclimatological studies. J Space Weather Space Clim 2:A09. https://doi.org/10.1051/swsc/2012009

Fergus CE, Finley AO, Soranno PA, Wagner T (2016) Spatial variation in nutrient and water color effects on lake chlorophyll at macroscales. PLoS ONE 11(10):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164592

Filazzola A, Mahdiyn O, Shuvo A, Ewins C, Moslenko L, Sadid T et al. (2020) A global database of chlorophyll and water chemistry in freshwater lakes. Sci Data

Filstrup CT, Downing JA (2017) Relationship of chlorophyll to phosphorus and nitrogen in nutrient-rich lakes. Inland Waters 7(4):385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/20442041.2017.1375176

Filstrup CT, Wagner T, Soranno PA, Stanley EH, Stow CA, Webster KE, Downing JA (2014) Regional variability among nonlinear chlorophyll-phosphorus relationships in lakes. Limnol Oceanogr 59(5):1691–1703. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2014.59.5.1691

Flato G, Marotzke J, Abiodun B, Braconnot P, Chou SC, Collins W et al (2013) Evaluation of climate models. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner GK, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (eds) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York

Gan C-M, Pleim J, Mathur R, Hogrefe C, Long CN, Xing J et al (2014) Assessment of the effect of air pollution controls on trends in shortwave radiation over the United States from 1995 through 2010 from multiple observation networks. Atmos Chem Phys 14:1701–1715

Hanna M, Peters RH (1991) Effect of sampling protocol on estimates of phosphorus and chlorophyll concentrations in lakes of low to moderate trophic status. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 48(10):1979–1986

Harris I, Osborn TJ, Jones P, Lister D (2020) Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci Data. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0453-3

Hayes NM, Vanni MJ (2018) Microcystin concentrations can be predicted with phytoplankton biomass and watershed morphology. Inland Waters 8(3):273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/20442041.2018.1446408

Heffernan JB, Soranno PA, Angilletta MJ Jr, Buckley LB, Gruner DS, Keitt TH, Kellner JR, Kominoski JS, Rocha AV, Xiao J, Harms TK, Goring SJ, Koenig LE, McDowell WH, Powell H, Richardson AD, Stow CA, Vargas R, Weathers KC (2014) Macrosystems ecology: understanding ecological patterns and processes at continental scales. Front Ecol Environ 12:5–14. https://doi.org/10.1890/130017

Hennemann MC, Petrucio MM (2016) High chlorophyll a concentration in a low nutrient context: discussions in a subtropical lake dominated by cyanobacteria. J Limnol. https://doi.org/10.4081/jlimnol.2016.1347

Ho JC, Michalak AM, Pahlevan N (2019) Widespread global increase in intense lake phytoplankton blooms since the 1980s. Nature 574:667–670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1648-7

Huang J, Xu Q, Xi B, Wang X, Jia K, Huo S et al (2014) Effects of lake-basin morphological and hydrological characteristics on the eutrophication of shallow lakes in eastern China. J Great Lakes Res 40(3):666–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2014.04.016

Jeppesen E, Kronvang B, Meerhoff M, Søndergaard M, Hansen KM, Andersen HE et al (2009) Climate change effects on runoff, catchment phosphorus loading and lake ecological state, and potential adaptations. J Environ Qual 38(5):1930–1941. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2008.0113

Jöhnk KD, Huisman J, Sharples J, Sommeijer B, Visser PM, Stroom JM (2008) Summer heatwaves promote blooms of harmful cyanobacteria. Glob Change Biol 14(3):495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01510.x

Karlsson KG, Riihelä A, Müller R, Meirink JF, Sedlar J, Stengel M et al (2013) CLARA-A1: a cloud, albedo, and radiation dataset from 28 year of global AVHRR data. Atmos Chem Phys 13(10):5351–5367. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-5351-2013

Kelling S, Hochachka WM, Fink D, Riedewald M, Caruana R, Ballard G, Hooker G (2009) Data-intensive science: a new paradigm for biodiversity studies. BioScience 59(7):613–620

Kolzau S, Wiedner C, Rücker J, Köhler J, Köhler A, Dolman AM (2014) Seasonal patterns of Nitrogen and Phosphorus limitation in four German Lakes and the predictability of limitation status from ambient nutrient concentrations. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096065

Kraemer BM, Mehner T, Adrian R (2017) Reconciling the opposing effects of warming on phytoplankton biomass in 188 large lakes. Sci Rep 7(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11167-3

Legendre P, Legendre LF (2012) Numerical ecology. Elsevier, New York

Lennard C (2019) Multi-Scale Drivers of the South African Weather and Climate. The Geography of South Africa. Springer, Cham, pp 81–89

Levy O, Ball BA, Bond-Lamberty B, Cheruvelil KS, Finley AO, Lottig NR, Punyasena SW, Xiao J, Zhou J, Buckley LB, Filstrup CT, Keitt TH, Kellner JR, Knapp AK, Richardson AD, Tcheng D, Toomey M, Vargas R, Voordeckers JW, Wagner T, Williams JW (2014) Approaches to advance scientific understanding of macrosystems ecology. Frontiers Ecology Environ 12(1):15–23. https://doi.org/10.1890/130019

Liaw A, Wiener M (2002) Classification and Regression by randomForest. R News 2(3):18–22

Liu W, Li S, Bu H, Zhang Q, Liu G (2012) Eutrophication in the Yunnan Plateau lakes: the influence of lake morphology, watershed land use, and socioeconomic factors. Environ Sci Pollut Res 19(3):858–870

Long CN, Dutton EG, Augustine JA, Wiscombe W, Wild M, McFarlane SA, Flynn CJ (2009) Significant decadal brightening of downwelling shortwave in the continental United States. J Geophys Res 114:D00D06. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD011263

Mateos D, Sanchez-Lorenzo A, Antón M, Cachorro VE, Calbó J, Costa MJ et al (2014) Quantifying the respective roles of aerosols and clouds in the strong brightening since the early 2000s over the Iberian Peninsula. J Geophys Res Atmos 119:10382–10393. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD022076

McCauley E, Downing JA, Watson S (1989) Sigmoid relationships between nutrients and chlorophyll among lakes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 46(7):1171–1175. https://doi.org/10.1139/f89-152

McCullough IM, Cheruvelil KS, Collins SM, Soranno PA (2019) Geographic patterns of the climate sensitivity of lakes. Ecol Appl 29(2):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1836

McQueen DJ, Lean DRS (1987) Influence of water temperature and nitrogen to phosphorus ratios on the dominance of blue-green algae in Lake St. George, Ontario. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 44(3):598–604. https://doi.org/10.1139/f87-073

Messager ML, Lehner B, Grill G, Nedeva I, Schmitt O (2016) Estimating the volume and age of water stored in global lakes using a geo-statistical approach. Nat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13603

Michalak AM (2016) Study role of climate change in extreme threats to water quality. Nature 535(7612):349–350

Michener WK, Jones MB (2012) Ecoinformatics: supporting ecology as a data-intensive science. Trends in ecology & evolution 27(2):85–93

Morris DP, Lewis WM (1988) Phytoplankton nutrient limitation in Colorado mountain lakes. Freshw Biol 20(3):315–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1988.tb00457.x

Nõges T (2009) Relationships between morphometry, geographic location and water quality parameters of European lakes. Hydrobiologia 633(1):33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-009-9874-x

O’Reilly CM, Sharma S, Gray DK, Hampton SE, Read JS, Rowley RJ et al (2015) Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophys Res Lett 42:10773–10781. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066235

Paerl HW, Scott JT, McCarthy MJ, Newell SE, Gardner WS, Havens KE et al (2016) It takes two to tango: when and where dual nutrient (N and P) reductions are needed to protect lakes and downstream ecosystems. Environ Sci Technol 50(20):10805–10813. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b02575

Peters DP, Bestelmeyer BT, Turner MG (2007) Cross–scale interactions and changing pattern–process relationships: consequences for system dynamics. Ecosystems 10(5):790–796

Prairie YT, Duarte CM, Kalff J (1989) Unifying nutrient-chlorophyll relationships in lakes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 46:1176–1182

Preston DL, Caine N, McKnight DM, Williams MW, Hell K, Miller MP et al (2016) Climate regulates alpine lake ice cover phenology and aquatic ecosystem structure. Geophys Res Lett 43(10):5353–5360. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069036

Quinlan R, Filazzola A, Mahdiyan O, Shuvo A, Blagrave K, Ewins C et al (2020) Relationships of total phosphorus and chlorophyll in lakes worldwide. Limnol Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11611

Rose KC, Greb SR, Diebel M, Turner MG (2017) Annual precipitation regulates spatial and temporal drivers of lake water clarity. Ecol Appl 27(2):632–643

Sanchez-Lorenzo A, Wild M, Brunetti M, Guijarro JA, Hakuba MZ, Calbó J, Mystakidis S, Bartok B (2015) Reassessment and update of long-term trends in downward surface shortwave radiation over Europe (1939–2012). J Geophys Res Atmos 120:9555–9569. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015JD023321

Schindler DW (1997) Evolution of phosphorus limitation in lakes. Science 195:260–262

Schmid M, Köster O (2016) Excess warming of a Central European lake driven by solar brightening. Water Resour Res 52(10):8103–8116

Schmid M, Hunziker S, Wueest A (2014) Lake surface temperatures in a changing climate: a global sensitivity analysis. Clim Change 124:301–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1087.2

Sharpley A, Jarvie HP, Buda A, May L, Spears B, Kleinman P (2013) Phosphorus legacy: overcoming the effects of past management practices to mitigate future water quality impairment. J Environ Qual 42(5):1308–1326. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2013.03.0098

Sinha E, Michalak AM, Balaji V (2017) Eutrophication will increase during the 21st century as a result of precipitation changes. Science 357(6349):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan2409

Smith VH, Schindler DW (2009) Eutrophication science: where do we go from here? Trends Ecol Evol 24(4):201–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.11.009

Soranno PA, Cheruvelil KS, Webster KE, Bremigan MT, Wagner T, Stow CA (2010) Using landscape limnology to classify freshwater ecosystems for multi-ecosystem management and conservation. Bioscience 60(6):440–454. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2010.60.6.8

Tian W, Zhang H, Zhao L, Zhang F, Huang H (2017) Phytoplankton diversity effects on community biomass and stability along nutrient gradients in a eutrophic lake. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010095

Trolle D, Hamilton DP, Pilditch CA, Duggan IC, Jeppesen E (2011) Predicting the effects of climate change on trophic status of three morphologically varying lakes: implications for lake restoration and management. Environ Modell Softw 26(4):354–370

Vargas R, Carbone MS, Reichstein M, Baldocchi DD (2011) Frontiers and challenges in soil respiration research: from measurements to model-data integration. Biogeochemistry 102(1–3):1–13

Vaughan IP, Gotelli NJ (2019) Water quality improvements offset the climatic debt for stream macroinvertebrates over twenty years. Nat Commun 10(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09736-3

Verburg P, Hecky RE, Kling H (2003) Ecological consequences of a century of warming in Lake Tanganyika. Science 301(5632):505–507

Wagner T, Soranno PA, Webster KE, Cheruvelil KS (2011) Landscape drivers of regional variation in the relationship between total phosphorus and chlorophyll in lakes. Freshw Biol 56(9):1811–1824

Webb JR, Hayes NM, Simpson GL, Leavitt PR, Baulch HM, Finlay K (2019) Widespread nitrous oxide undersaturation in farm waterbodies creates an unexpected greenhouse gas sink. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116(20):9814–9819. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820389116

Wild M (2012) Enlightening global dimming and brightening. Bull Am Meteor Soc 93(1):27–37. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00074.1

Wild M, Gilgen H, Roesch A, Ohmura A, Long CN, Dutton EC et al (2005) From dimming to brightening: decadal changes in solar radiation at earth’s surface. Science 308(5723):847–850. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103215

Wild M, Folini D, Henschel F, Fischer N, Müller B (2015) Projections of long-term changes in solar radiation based on CMIP5 climate models and their influence on energy yields of photovoltaic systems. Sol Energy 116:12–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2015.03.039

Woelmer WM, Kao YC, Bunnell DB, Deines AM, Bennion DH, Rogers MW et al (2016) Assessing the influence of watershed characteristics on chlorophyll a in waterbodies at global and regional scales. Inland Waters 6(3):379–392. https://doi.org/10.5268/IW-6.3.964

Zhang Y, Qin B, Shi K, Zhang Y, Deng J, Wild M, Li L, Zhou Y, Yao X, Liu M, Zhu G, Zhang L, Gu B, Brookes JD (2020) Radiation dimming and decreasing water clarity fuel underwater darkening in lakes. Sci Bull 65:1675–1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.06.0162095-9273/

Zhong Y, Notaro M, Vavrus SJ, Foster MJ (2016) Recent accelerated warming of the Laurentian Great Lakes: physical drivers. Limnol Oceanogr 61:1762–1786. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10331

Acknowledgements

All data used in this study are publicly accessible. Funding for this study was provided by the Ontario Ministry of Innovation Early Researcher Award, York Research Chair and Natural Sciences Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant to SS, and the Ontario Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Best in Science Grant to DG and SS. SS and DG secured funding for the project; SS led the project. AF, KB, AS, LM, CE, and OM assembled the dataset; AS, AF, and DG conducted analyses; KB and AS made figures; SS, COR, AS, OM, and DG wrote sections of the text. All authors contributed ideas, editing and revision. Authors between the co-leads and last author had similar contributions and are listed in alphabetical order.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Ontario Ministry of Innovation Early Researcher Award, York Research Chair and Natural Sciences Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant to Dr. Sapna Sharma (SS), and the Ontario Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Best in Science Grant to Derek Gray (DG) and SS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS led the project. AF, KB, AS, LM, CE, and OM assembled the dataset; AS, AF, and DG conducted analyses; KB and AS made figures; SS, COR, AS, OM, and DG wrote sections of the text. All authors contributed ideas, editing and revision. Authors between the co-leads and last author have similar contributions and are listed in alphabetical order.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shuvo, A., O’Reilly, C.M., Blagrave, K. et al. Total phosphorus and climate are equally important predictors of water quality in lakes. Aquat Sci 83, 16 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-021-00776-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-021-00776-w