Abstract

An increasing oversupply of clothing is linked to harmful environmental impacts. Women workers in the textile industry are exposed to poor working conditions. Renting clothing for a period of time instead of buying, using and disposing the garments is an emerging business model that might be suited to fulfill customers’ needs for varied clothing while reducing the number of garments purchased and therefore the environmental impacts of the industry. This chapter presents a methodology to assess the environmental impacts of the use-based product-service systems (PSS) with the help of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) using the example of clothing rental in Germany. Based on different scenarios, fashionistas are identified as a target group who can reduce their personal environmental impacts by adopting a rental model.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The current state of the clothing and textile as well as a rising demand for cheap clothes are linked to harmful impacts on the environment as well as poor working conditions of the people involved in the manufacturing of clothes [2, 11]. Business models of the Sharing Economy try to lower the environmental and social impacts of consumption by offering ways to have access to goods different from conventional consumption (in this chapter defined as the purchase, use and disposal of goods by one person). One emerging business model is the offer to rent garments for a certain period [1, 7]. While sharing goods might reduce the environmental impacts, this is not a given for every offer and every person. Therefore, the environmental impacts of newly emerging business models should be assessed to allow for a comparison with conventional ways of consumption as well as the optimization of the offering and derivation of guidelines for users.

The chapter presents the business model of renting clothes and outlines the challenges of assessing Product-Service Systems (PSS) with the help of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Subsequently, a methodological approach to assess the change of personal environmental impact if a rental offer is adapted by a single female user in Germany is presented. A result matrix of the 54 assessed scenarios and recommendations for users and companies offering clothing for rent closes the chapter.

1 Business Model: Renting of Leisurewear

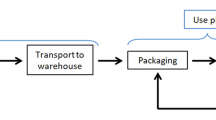

Over the last two decades, start-ups that offer to rent garments online or offline instead of buying them appeared worldwide [6]. While offering additional services like styling advice, cleaning services, flat rate subscription and a broad range of styles from local designers to haute couture pieces is available, the basic process diagram looks similar for most of the services. An overview is depicted in Fig. 1. The diagram is based on research and interviews with start-up founders.

The conventional value chain is shown on the top left while the circle on the right represents the renting of garments which can be classified as a use-oriented product-service system according to [16]. PSS are defined as “a marketable set of products and services capable of jointly fulfilling a user´s need” [3]. According to [16, 17], PSS have the potential to lower the environmental impacts of consumption depending on the design of the business model and behavior of the users.

As mentioned before, assessing the environmental impacts of PSS presents a challenge as the scope of the study exceeds the typical stages of a products life cycle and to be able to derive whether the adaption of a rental PSS is less harmful to the environment, different patterns of consumption instead of just two products have to be compared.

2 Challenges of Assessing the Environmental Impacts of a Product-Service System

Kjær et al. [9] point out that the assessment of the environmental impact of PSS using Life Cycle Assessment (described in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044) is challenging and also offering guidance on how to conduct a study [10]. According to the authors, the three main challenges applying LCA to a PSS are as follows:

-

Identifying and defining the reference system.

-

Defining the functional unit.

-

Setting system boundaries.

While the more traditional application of attributional LCA is to assess the environmental impacts of one product over its life cycle from “cradle-to-grave” covering the conventional value chain (see Fig. 1 on the top left), the analysis of a PSS is more complex. It requires a broader view potentially covering various products and different activities, user behavior and the impact of the adaption of a PSS on the activities of the adopting users outside the direct use of the PSS.

The complexity starts at the beginning of the value chain. The global textile industry is vast and non-transparent. Raw materials, pre-products and garments are manufactured and shipped worldwide. Many pieces will never be used, and the total amount of garments manufactured and disposed is not publicly available and most likely unknown. During use, data collection presents a challenge as well. Especially regarding the consumption and use of garments, behavior and customs of people are varied and diverse. Regarding the disposal or prolonging of the life cycle of garments, fabrics and fibers, some data is available but might neglect a dark figure of stored, gifted or thrown away pieces.

To address those challenges and to offer one potential solution, a method to assess the environmental impacts of the adoption of a rental PSS for leisurewear from a consumer perspective was developed.

3 Approach: LCA of a PSS from a Consumer Perspective

A first version of the methodology was presented in Piontek et al. [12] before the approach was applied on a generic business model based on renting leisurewear to female consumers in Germany using the functional unit “One year of varied clothing (for a female consumer in Germany)”. The method allocates the environmental impacts of activities related to clothing consumption to one consumer. The production of the garments is allocated by considering the share of the lifetime of each garment if it is accessible by the consumer either because she owns it or because it was part of a parcel received from the rental company.

To cover the broad range of varieties described in the previous section, 54 scenarios have been composed of different blocks. The scheme is shown in Fig. 2.

Combination of scenarios I (based on [14] (CC BY 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0))

Three types of consumers, based on the frequency of purchases and the time they use the garments, have been combined with their respective End-of-Life (EoL) scenarios. The baseline numbers are based on publications by Spiegel-Verlag [15], Greenpeace e.V. [4] and Geiger et al. [5]. Fashionistas are consumers who buy twice the number of garments and use them half of the time compared to the Baseline while conscious consumers are buying half of the clothing and using it for twice the amount of time.

At the EoL, the same amount of clothing as purchased (or the allocated amount for a rental model used during the reference year) is disposed by considering 55% of garments to be reused as second-hand garments (replacing garments), 35% reused as downcycled products (replacing primary fibers) and 10% of incineration. This might be highly different for other countries or depending on the quality of the garments as well as the way to dispose them chosen by the user.

For each consumer type, three modes of consumption have been considered: Conventional consumption and two versions of a monthly received parcel from a rental provider containing more basic clothes (like Shirts and pullovers, Rental 1) or the rental of more complex garments like a coat or dresses (Rental 2). Additionally, two types of behavior have been considered: The mileage driven in a car related to the PSS (e.g., picking up a parcel from the post-office) or shopping activities and two scenarios for laundry care. The way the different behavioral patterns are combined is shown in Fig. 3. Every variation chosen influences one or more “blocks” of the reference flow. For example, the behavior during use is represented by one block for the use of a car and one block for laundry care. All blocks are summed to generate the combined reference flow of each scenario and finally the related environmental impacts.

Combination of scenarios II (based on [14] (CC BY 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0))

Three examples for a scenario are as follows:

-

A Baseline consumer, driving 10 km per week, worst case laundry care, having adopted rental scheme 1, disposing the respective garments at the end of their service life.

-

A Conscious Consumer, driving 20 km per week, best case laundry care, buying clothing the conventional way, disposing the respective garments at the end of their service life.

-

A fashionista, not using a car, best case laundry care, having adopted rental scheme 2, disposing the respective garments at the end of their service life.

The resulting 54 scenarios span a result space showing extremes and various combinations of behavior to allow for an analysis of hotspots and the derivations of findings. It may not be the case that a person finds herself in exactly one scenario or that a certain combination of “blocks” might seem reasonable for a certain group of people (e.g., consumers who despite being environmentally conscious, also driving a lot), but the result space should allow for the deduction of findings and the analysis of trends.

4 Findings, Recommendations and Limitations

Based on Life Cycle Inventories (LCI) for each scenario created using data from the GaBi databases provided by Sphera and a Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) using endpoint indicators from ReCiPe v1.1 (H), the matrix shown in Fig. 4 has been created.

Result matrix (based on [14] (CC BY 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0))

At first glance at the matrices, it is obvious that a noteworthy reduction of environmental impacts only occurs for the user group “Fashionista”. An adaption of a rental PSS can satisfy their need for access to different styles while reducing the environmental impacts compared to conventional consumption if the purchase of new garments is substituted by the adaption of the PSS. This is in line with the findings of other publications [8, 13, 18].

For a Baseline consumer, the adaption of the rental scheme offering more complex garments is linked to a slight reduction of environmental impacts for two out of three endpoint categories. For a conscious consumer, the environmental impacts are higher for nearly every impact category if compared to conventional (conscious) consumption.

An analysis at the midpoint level has shown that hotspots of the analysis in categories like global warming potential or particular matter formation are indeed also the use of a car as well as the energy consumption related to laundry care. Therefore, for users of rental PSS, it is recommended that they substitute the purchase of new garments by adapting a PSS and reflect on whether a subscription model is needed to satisfy their personal needs regarding the variety of clothing. The reduced usage of a combustion engine car as well as the optimization of the laundry care routine toward energy savings can also lower the personal impact on the environment.

If providers of rental clothing want to contribute to lower environmental impacts, they should address the right target group to avoid the rebound effect of incentivizing additional consumption and resource use. To replace the production of new garments, which is necessary to lower the overall impacts of consumption, the pieces offered by a rental provider should be long-lasting—both, in terms of technical life and fashion relevance. Additional offerings like style advice or the note that a customer can send the garments back without washing them before are options to strengthen customer satisfaction and lower environmental impacts. While not being assessed in a scenario, a flat rate offer, allowing a user to send back the parcels after even one day, might lead to significant rebound effects due to transportation and cleaning of the garments.

The methodology and results presented are object to several limitations. The scenarios are based on selective data sources, as data on the production and use of clothing is not available in a high level of detail. As the environmental impacts are assessed from the point of view of a single female user in Germany, the results might be different for different countries and forms of the available rental offerings including different kinds of styles, garments and subscription models. Also, the impacts on the textile industry on a systemic level are out of the scope of the study.

5 Conclusion and Further Research

An LCA approach to assess rental business models has been presented. The emerging offering of renting leisurewear instead of buying, using and disposing garments in the conventional way has been chosen as the exemplary case study for the methodology. Findings from a result space opened up by 54 scenarios show that people who want to wear a broad range of different garments can lower their environmental footprint by adopting a rental model as long as the purchase of new garments is substituted. Others, especially conscious consumers might experience rebound effects linked to additional laundry care, transport and packaging linked to the rental scheme. Despite the consumption pattern, the change in the use of a combustion engine car and laundry care might have the potential to save environmental impacts.

For further research, the methodology could be adapted to other industries and goods like bikes, cars or tools available to be rented from DIY stores as well as outdoor equipment like tents and hiking backpacks. In the space of clothing, stationary rental offerings instead of online ones could be analyzed. A broader scope trying to include systemic changes using either consequential LCA or modeling methods like system dynamics could prove to lead to interesting findings as well.

References

Armstrong CM, Niinimäki K, Kujala S, Karell E, Lang C (2015) Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. J Clean Prod 97:30–39

Fletcher K (2013) Sustainable fashion and textiles: design journeys. Routledge

Goedkoop MJ, Van Halen CJ, Te Riele HR, Rommens PJ (1999) Product service systems, ecological and economic basics. Report for Dutch Ministries of environment (VROM) and economic affairs (EZ) 36(1):1–122

Greenpeace EV (2015) Wegwerfware Kleidung

Geiger S, Iran S, Müller M (2017) Nachhaltiger Kleiderkonsum in Dietenheim. Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Umfrage zum Kleiderkonsum in einer Kleinstadt im ländlichen Raum in Süddeutschland

Henninger CE, Amasawa E, Brydges T, Piontek FM (2022) My wardrobe in the cloud: an international comparison of fashion rental. In: Handbook of research on the platform economy and the evolution of e-commerce. IGI Global, pp 153–175

Iran S, Schrader U (2017) Collaborative fashion consumption and its environmental effects. J Fashion Market Manage Int J

Johnson E, Plepys A (2021) Product-service systems and sustainability: analyzing the environmental impacts of rental clothing. Sustainability 13(4):2118

Kjær LL, Pagoropoulos A, Schmidt JH, McAloone TC (2016) Challenges when evaluating product/service-systems through life cycle assessment. J Clean Prod 120:95–104

Kjær LL, Pigosso DC, McAloone TC, Birkved M (2018) Guidelines for evaluating the environmental performance of product/service-systems through life cycle assessment. J Clean Prod 190:666–678

Kozlowski A, Bardecki M, Searcy C (2012) Environmental impacts in the fashion industry: a life-cycle and stakeholder framework. J Corp Citizsh 45:17–36

Piontek FM, Rehberger M, Müller M (2019) Development of a functional unit for a product service system: one year of varied use of clothing. In: Progress in life cycle assessment. Springer, Cham, pp 99–104

Piontek FM, Amasawa E, Kimita K (2020) Environmental implication of casual wear rental services: case of Japan and Germany. Procedia CIRP 90:724–729

Piontek FM (2022) Ökobilanzierung von Product-Service Systems: Ein Beitrag anhand des Mietens von Freizeitkleidung. Doctoral dissertation, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany. Retrieved from https://oparu.uni-ulm.de/xmlui/handle/123456789/46571.

SPIEGEL-Verlag (2016) Outfit 9.0 Zielgruppen – Marken – Medien

Tukker A (2004) Eight types of product–service system: eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus Strateg Environ 13(4):246–260

Tukker A (2015) Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy: a review. J Clean Prod 97:76–91

Zamani B, Sandin G, Peters GM (2017) Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? J Clean Prod 162:1368–1375

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Piontek, F.M., Müller, M. (2023). Life Cycle Assessment of the Renting of Leisurewear. In: Muthu, S.S. (eds) Progress on Life Cycle Assessment in Textiles and Clothing. Textile Science and Clothing Technology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9634-4_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9634-4_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-9633-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-9634-4

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)