Abstract

Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are rare and relatively benign tumors, with a malignancy ratio of 10–15%. The utility of multiple imaging modalities, combining with age and gender profile, is crucial for the diagnosis of SPNs. At present, surgery remains the only curative method for SPNs. While opinions towards surgical procedures are highly divided due to its rarity, minimally invasive procedures for SPNs are gradually recommended, whether extent of resection or surgical path. Although patients with SPNs always have a favorable prognosis, postoperative follow-ups remain essential. In general, we mainly discussed the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up for patients with SPNs.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Pancreatic solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are rare, accounting for 1–2% and 5% of pancreatic exocrine neoplasms and pancreatic cystic neoplasms, respectively [1]. SPNs are relatively benign neoplasms with a malignancy rate of 10–15% [2]. The mutation of CTNNB1, present in over 90% of cases, is a molecular hallmark of the disease, leading to the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [3, 4]. SPNs are mostly found in younger women [5], with a female to male ratio of 10:1 [6]. The symptoms are not well-defined, but the most common symptom is abdominal discomfort, which is present in over half of patients [7]. In addition, about a third of patients are asymptomatic. There is no significant difference in presentation between men and women [8], nor in symptom and tumor characteristics between children and adults [9, 10].

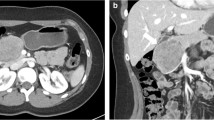

Radiological examinations are important for SPNs diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) is the most commonly used imaging modality, followed by ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [7]. The combination of imaging manifestations of US, CT, and MRI is crucial for the diagnosis of SPNs [11]. However, the CT imaging features of SPNs are different between males and females, such as tumor shape and tumor composition. Tumor imaging in male patients always features a solid mass with lobulated margin and progressive enhancement [12]. Compared to symptomatic SPNs, asymptomatic ones have significantly smaller tumor size and may lack the typical features [13, 14]. The characteristic imaging manifestation combined with age and gender profile may be sufficient for most SPNs diagnosis [15]. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is a accurate diagnosis method with sensitivity and specificity as high as 91% and 94%, respectively. However, the procedure of FNA may entail certain risks, such as hemorrhage, pancreatitis, pancreatic fistula, gastrointestinal perforation, and even tumor cells dissemination [15]. Previous studies recommended that laparoscopic biopsy should be avoided due to the risk of tumor recurrence and peritoneal dissemination [16,17,18]. In addition to diagnosis, the preoperative imaging workups are helpful for discriminating between potentially malignant and benign tumors to guide clinical treatment options. Previous studies have indicated that preoperative CT imaging may be helpful to discriminate aggressive SPNs from non-aggressive tumors [12]. Incomplete capsule, ill-defined margin, and absence of bleeding feature in CT imaging are risk factors for aggressive SPNs, which could be used to guide the preoperative selection of surgical procedure. In addition to radiographic results, researchers have also found that preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is predictive of malignant SPNs [19].

At present, surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for SPNs, which is recommended by the 2017 International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) and the 2018 European Pancreatic Club guidelines [20,21,22]. The common surgical procedures for SPNs generally include enucleation, segmental pancreatectomy, and pancreaticoduodenectomy, which depend on the location of the tumor [23]. Tumors located in the head or uncinate of the pancreas require enucleation, or pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without pylorus-preserving. For tumors located in the neck or body of the pancreas, surgeons could resect the midportion of the pancreas or perform enucleation. Distal pancreatectomy (DP) with or without splenectomy is often performed for SPNs located in the body or tail of the pancreas [2, 15, 24]. However, there is currently no uniform standard on the selection of surgical procedures. The procedure may be performed either laparoscopically or by open surgery and could be aggressive or function-preserving. The lack of a golden standard is partially due to the rarity of SPNs, and that the current experience is mostly based on the small-scale studies or case reports.

Due to the favorable prognosis and low-grade malignancy of SPNs, pancreatic function and adjacent organ preserving surgery has been proposed by multiple studies [25]. Deficient residual volume of the pancreas is correlated with pancreatic functional deficiency [26]. Previous studies have shown that enucleation could be performed for SPNs located within the head, neck, or body of the pancreas, especially with no indications of dilated pancreatic duct and/or common bile duct [23]. However, opinions regarding such a surgical procedure are highly divided. Some studies maintained that enucleation is indicated for smaller tumors [24], while others considered that it should not be performed because of the increased risk of dissemination, recurrence, and pancreatic fistula [2, 27]. For SPNs in children, enucleation may be a safe and effective surgical procedure if taking tumor size and location into consideration, but it correlates with increased risk of prolonged fasting times and development of pancreatic fistula [28]. Enucleation may be more beneficial for children than adults with SPNs, because it could preserve the exocrine and endocrine functions of the pancreas to the greatest extent. However, because age < 13.5 is associated with a higher risk of recurrence [29], surgeons should balance the benefits and risks of enucleation. Whether enucleation should be performed on patients with SPNs and the selection of patients for enucleation require future researches.

Patients undergoing Whipple’s procedure experience significantly longer postoperative hospitalization and increased unadjusted mortality than segmental pancreatectomy, while with no significant difference in postoperative complication rates [30]. Compared to conventional DP, spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy (SPDP) may reduce the risk of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection, without increasing the complication rate and prolonging postoperative hospitalization [31, 32]. It appears that function or organs preserving surgery is superior to invasive surgery. The function or organ preserving surgery could preserve the function of digestive system, pancreas, or spleen to a large extent, which is crucial for the life quality of patients, especially for younger ones. However, some studies have indicated that parenchyma-preserving surgical procedure is associated with an increased risk for postoperative recurrence due to the incomplete resection [33].

When it comes to the surgical path, laparoscopic surgery is recently becoming more prevalent with the improvement of surgical techniques. Shorter time to diet and postoperative hospitalization, lower intraoperative blood loss and transfusion requirement, and lower complication rates have been previously observed in minimally invasive pancreatectomy (MIP) for SPNs than open groups [34, 35]. However, laparoscopic management may be correlated with a higher risk of local or disseminated recurrence than open laparotomy [36].

There is a growing body of literature that recommends function-preserving and laparoscopic surgery for SPNs due to low-grade malignancy, but routine lymphadenectomy is not indicated because of the rarity of metastasis [15]. However, patients with preoperative imaging workups or histopathological examination showing high-grade malignancy, such as locally advanced tumors or distant metastasis, require more aggressive surgical procedures [37, 38]. For instance, patients with portal-superior mesenteric vein (PV/SMV) and/or adjacent organ involvement, who underwent en bloc primary tumor excision with synchronous PV/SMV and/or adjacent organ resection could obtain a good prognosis [39]. The principle of surgical management for patients with distant metastasis is to resect both the primary and metastatic tumors as completely as possible [40]. But for patients with unresectable tumors of SPNs, adjuvant radiation, chemotherapy, vascular resection and reconstruction, and liver transplantation may be acceptable options, but the evidence level is relatively low [41,42,43,44].

Although patients with SPNs always have a favorable prognosis, with the 5-year survival rate of more than 95% [15, 45], postoperative follow-ups remain essential. The majority of recurrences or metastases occur within 5 years after surgery. However, in a small but significant number of patients, recurrence or metastasis has been seen between 5 and 10 years. Long-term follow-ups are needed to examine the outcome of surgery for patients with SPNs. About 2% of patients who underwent surgical resection experience recurrence after surgery [46]. Over the last decades, the factors suggesting malignant potential of SPNs have been broadly explored, which could predict surgical outcome and guide postoperative follow-ups. Extensive researches have shown that tumor size and microscopic malignant features are significant prognostic factors for postoperative recurrence [47,48,49]. Besides, multiple large-scale studies have demonstrated that blood vessel invasion and larger tumor size may be associated with high-grade malignancy [48, 50, 51]. However, previous studies have shown differences in predictive ability and cut-off value of tumor size to predict recurrence [52, 53]. Recently, Yang et al. have shown that the combination of Ki-67 and tumor size is helpful to predict postoperative recurrence, superior to the current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) staging systems [54]. Negative surgical margins are essential to avoid recurrence, and the intraoperative frozen section could be used for validation [55, 56]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis study that summarized the studies analyzing the relationships between clinicopathological factors and SPNs malignancy has found no reliable factor [57]. In addition to the clinicopathological characteristics, Cohen et al. analyzed the miRNA patterns among normal pancreas, primary tumors, and metastatic tumors through miRNA array. They found that lower expression of miR-375, miR-217, and miR-200c and higher expression of miR-184, miR-10a, and miR-887 are associated with metastasis [58]. However, even if patients relapsed at follow-up, reoperation could still result in long-term survival [24].

We herein summarize the diagnosis, treatment, and postoperative follow-up for patients with SPNs. Yet, the current literature regarding SPNs mostly come from case reports and studies by an isolated center with low levels of evidence. Regardless, minimally invasive procedures are increasingly being recommended for the treatment of SPNs, not only for the extent of resection but also as surgical path. Meanwhile, future studies should establish methods for more accurate preoperative diagnosis and malignant markers. Large-scale multicenter studies are urgently needed to verify and update the current understanding of SPNs.

References

Klöppel G, Basturk O, Klimstra D, Lam A, Notohara K. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. In: Carneiro Fatima CJ, NYA C, et al., editors. Digestive system tumours, vol. 1. 5th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2019. p. 340–2.

Naar L, Spanomichou DA, Mastoraki A, Smyrniotis V, Arkadopoulos N. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: a surgical and genetic enigma. World J Surg. 2017;41(7):1871–81.

Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M, et al. A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1501–10.

Audard V, Cavard C, Richa H, et al. Impaired E-cadherin expression and glutamine synthetase overexpression in solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2008;36(1):80–3.

Stark A, Donahue TR, Reber HA, Hines OJ. Pancreatic cyst disease: a review. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1882–93.

Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(6):965–72.

Law JK, Ahmed A, Singh VK, et al. A systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: are these rare lesions? Pancreas. 2014;43(3):331–7.

Wang P, Wei J, Wu J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a single institution experience with 97 cases. Pancreatology. 2018;18(4):415–9.

Leraas HJ, Kim J, Sun Z, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas in children and adults: a national study of 369 patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;40(4):e233–6.

Waters AM, Russell RT, Maizlin, II, Group C, Beierle EA. Comparison of pediatric and adult solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J Surg Res. 2019;242:312–317.

Cheng DF, Peng CH, Zhou GW, et al. Clinical misdiagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumour of pancreas. Chin Med J. 2005;118(11):922–6.

Park MJ, Lee JH, Kim JK, et al. Multidetector CT imaging features of solid pseudopapillary tumours of the pancreas in male patients: distinctive imaging features with female patients. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1035):20130513.

Hu S, Zhang H, Wang X, et al. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: clinical and MDCT manifestations. Cancer Imaging. 2019;19(1):13.

Inoue T, Nishi Y, Okumura F, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas associated with familial adenomatous polyposis. Intern Med. 2015;54(11):1349–55.

Yang F, Fu DL, Jin C, et al. Clinical experiences of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(12):1847–51.

Petrosyan M, Franklin AL, Jackson HT, McGue S, Reyes CA, Kane TD. Solid pancreatic pseudopapillary tumor managed laparoscopically in adolescents: a case series and review of the literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24(6):440–4.

Butte JM, Brennan MF, Gonen M, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas. Clinical features, surgical outcomes, and long-term survival in 45 consecutive patients from a single center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(2):350–7.

Cavallini A, Butturini G, Daskalaki D, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatectomy for solid pseudo-papillary tumors of the pancreas is a suitable technique; our experience with long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(2):352–7.

Yang F, Bao Y, Zhou Z, Jin C, Fu D. Preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts malignancy and recurrence-free survival of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(2):241–8.

van Huijgevoort NCM, Del Chiaro M, Wolfgang CL, van Hooft JE, Besselink MG. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: current evidence and guidelines. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(11):676–89.

Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, Moayyedi P, Committee CG, Association AG. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(4):819–822; quize812–813.

Pancreas ESGoCTot. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67(5):789–804.

Chang H, Gong Y, Xu J, Su Z, Qin C, Zhang Z. Clinical strategy for the management of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: aggressive or less? Int J Med Sci. 2010;7(5):309–13.

Cai Y, Ran X, Xie S, et al. Surgical management and long-term follow-up of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas: a large series from a single institution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(5):935–40.

Liu M, Liu J, Hu Q, et al. Management of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of pancreas: a single center experience of 243 consecutive patients. Pancreatology. 2019;19(5):681–5.

DiNorcia J, Ahmed L, Lee MK, et al. Better preservation of endocrine function after central versus distal pancreatectomy for mid-gland lesions. Surgery. 2010;148(6):1247–1254; discussion 1254–1246.

Vassos N, Agaimy A, Klein P, Hohenberger W, Croner RS. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) of the pancreas: case series and literature review on an enigmatic entity. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(6):1051–9.

Cho YJ, Namgoong JM, Kim DY, Kim SC, Kwon HH. Suggested indications for enucleation of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms in pediatric patients. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:125.

Irtan S, Galmiche-Rolland L, Elie C, et al. Recurrence of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: results of a nationwide study of risk factors and treatment modalities. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(9):1515–21.

Manuballa V, Amin M, Cappell MS. Clinical presentation and comparison of surgical outcome for segmental resection vs. Whipple’s procedure for solid pseudopapillary tumor: Report of six new cases & literature review of 321 cases. Pancreatology. 2014;14(1):71–80.

Lee SE, Jang JY, Lee KU, Kim SW. Clinical comparison of distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23(6):1011–4.

He Z, Qian D, Hua J, Gong J, Lin S, Song Z. Clinical comparison of distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91593.

Tjaden C, Hassenpflug M, Hinz U, et al. Outcome and prognosis after pancreatectomy in patients with solid pseudopapillary neoplasms. Pancreatology. 2019;19(5):699–709.

Hao EIU, Rho SY, Hwang HK, et al. Surgical approach to solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the proximal pancreas: minimally invasive vs. open. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17(1):160.

Tan HL, Syn N, Goh BKP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of minimally invasive pancreatectomies for solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2019;48(10):1334–42.

Fais PO, Carricaburu E, Sarnacki S, et al. Is laparoscopic management suitable for solid pseudo-papillary tumors of the pancreas? Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25(7):617–21.

Kumar NAN, Bhandare MS, Chaudhari V, Sasi SP, Shrikhande SV. Analysis of 50 cases of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas: aggressive surgical resection provides excellent outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(2):187–91.

Kim CW, Han DJ, Kim J, Kim YH, Park JB, Kim SC. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: can malignancy be predicted? Surgery. 2011;149(5):625–34.

Cheng K, Shen B, Peng C, Yuan F, Yin Q. Synchronous portal-superior mesenteric vein or adjacent organ resection for solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: a single-institution experience. Am Surg. 2013;79(5):534–9.

Wang WB, Zhang TP, Sun MQ, Peng Z, Chen G, Zhao YP. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas with liver metastasis: clinical features and management. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(11):1572–7.

Sperti C, Berselli M, Pasquali C, Pastorelli D, Pedrazzoli S. Aggressive behaviour of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in adults: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(6):960–5.

Sumida W, Kaneko K, Tainaka T, Ono Y, Kiuchi T, Ando H. Liver transplantation for multiple liver metastases from solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(12):e27–31.

Ward HC, Leake J, Spitz L. Papillary cystic cancer of the pancreas: diagnostic difficulties. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28(1):89–91.

Maffuz A, Bustamante Fde T, Silva JA, Torres-Vargas S. Preoperative gemcitabine for unresectable, solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(3):185–6.

Yu PF, Hu ZH, Wang XB, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a review of 553 cases in Chinese literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(10):1209–14.

Yepuri N, Naous R, Meier AH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of predictors of recurrence in patients with Solid Pseudopapillary Tumors of the Pancreas. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22(1):12–9.

Kang CM, Choi SH, Kim SC, et al. Predicting recurrence of pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumors after surgical resection: a multicenter analysis in Korea. Ann Surg. 2014;260(2):348–55.

Kim MJ, Choi DW, Choi SH, Heo JS, Sung JY. Surgical treatment of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas and risk factors for malignancy. Br J Surg. 2014;101(10):1266–71.

Gao H, Gao Y, Yin L, et al. Risk factors of the recurrences of pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer. 2018;9(11):1905–14.

Wu JH, Tian XY, Liu BN, Li CP, Zhao M, Hao CY. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of pancreas. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2019;32(1(Special)):459–64.

Estrella JS, Li L, Rashid A, et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: clinicopathologic and survival analyses of 64 cases from a single institution. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(2):147–57.

Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Kim H, Lee WJ, Kim BR. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas suggesting malignant potential. Pancreas. 2006;32(3):276–80.

Machado MC, Machado MA, Bacchella T, Jukemura J, Almeida JL, Cunha JE. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: distinct patterns of onset, diagnosis, and prognosis for male versus female patients. Surgery. 2008;143(1):29–34.

Yang F, Wu W, Wang X, et al. Grading solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: the Fudan prognostic index. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020.

Canzonieri V, Berretta M, Buonadonna A, et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(4):255–6.

Ng KH, Tan PH, Thng CH, Ooi LL. Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73(6):410–5.

You L, Yang F, Fu DL. Prediction of malignancy and adverse outcome of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(7):184–93.

Cohen SJ, Papoulas M, Graubardt N, et al. Micro-RNA expression patterns predict metastatic spread in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Front Oncol. 2020;10:328.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wu, W., Xu, Q., Jiang, R. (2022). Pancreatic Resection for Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasms. In: Makuuchi, M., et al. The IASGO Textbook of Multi-Disciplinary Management of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Diseases. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0063-1_51

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0063-1_51

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-0062-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-0063-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)