Abstract

This chapter introduces a school-based teacher professional development (PD) approach adopted by a local secondary school in Singapore in its pursuit of sustaining teaching and learning practices that could support school improvement and achieve educational success in the twenty-first century. By comparing the structure and operational guidelines of this approach with the characteristics and guiding principles of effective PD programmes identified in the contemporary literature, we argue that the approach has great potential to succeed, considering its apparent affordances for a community that (1) involves whole-school participation, (2) facilitates individual and group learning, (3) cultivates a collegial culture of sharing and learning, (4) promotes shared leadership and (5) connects with external resources and communities. Despite its promising outlook, we suggest that empirical studies on the intended conditions, enacted process and achieved outcomes of this PD approach are needed for validation, refinement and sustainability purposes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The twenty-first century is an era of rapid social, economic and technological changes (Friedman, 2006). Educational success in the twenty-first century emphasizes the development of skills and competencies that go beyond routine cognitive tasks, such as the ability to critically seek and synthesize information, the ability to create and innovate and the ability to self-direct one’s learning (Dede, 2010). Education systems around the world are trying to improve their teaching and learning practices and make them relevant for the twenty-first century. Research has consistently shown that the most important determinant of students’ learning experiences and outcomes is the quality of teaching (e.g. Hattie, 2003). Professional development (PD) for teachers is critical because teacher growth impacts the quality of teaching and learning (Mourshed et al., 2010). This chapter starts with a brief discussion of the contemporary research agenda in teacher PD in global contexts, highlighting the three fundamental dimensions of teacher PD and identified characteristics of effective teacher PD programmes. After that, the development of teacher PD in the context of Singapore is presented, followed by the introduction of an exploratory approach to teacher PD adopted by a local secondary school in Singapore. Finally, we examine the structures and operational guidelines of this approach by comparing them with the key features of quality PD programmes highlighted in the literature to reveal its potential and challenges. Implications of this school-based PD approach on educational research are then discussed.

2 Research Agenda in Teacher PD in Global Contexts

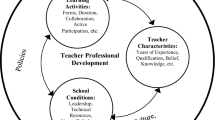

In this section, we first discuss the three fundamental dimensions of teacher PD, namely context, enactment and outcome, as well as the contemporary research agenda related to these three dimensions. We then look into the key features and operational principles of effective teacher PD programmes advocated by educational researchers.

2.1 The Fundamental Dimensions of Teacher PD

Context of teacher PD: Adult learners are self-directed, ready to learn, experienced, task-centred and intrinsically motivated (Knowles, 1983). Thus, adult learners can be synergized by situating learning at the workplace. A plethora of research on teacher PD has recognized the limitations of short-term PD conducted by external institutions on teacher learning, and researchers have reiterated that effective and sustained teacher learning has to be contextualized and situated within their respective school settings (Avalos, 2011; Campbell, 2011; Garet et al., 2001; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). A situative approach to teacher learning strives to engage teachers, either individually or collectively, in actively working on authentic and genuine problems within their professional practices in school contexts (Borko, 2004; Bound & Middleton, 2003; Putnam & Borko, 2000). Situative theorists conceptualize learning as changes in participation in socially organized activities and individuals’ use of knowledge as an aspect of their participation in social practices (Greeno, 2003; Lave & Wenger, 1991). This form of contextualized teacher learning is seen as a powerful way to enhance teacher autonomy and teacher agency (Campbell, 2012; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012; Schon, 1983, 1987). Teacher PD that augments teacher autonomy and agency increases teachers’ capacity to make informed discretionary judgement and solve complex issues at work collaboratively. For example, solving complex problems at work is a professional practice that requires practical knowledge, rather than intellectual and rational knowledge that may only be marginally relevant to practice (Schon, 1987). However, teacher knowledge must also play an active and dynamic role in the ever-changing challenges of the school and classroom (Manen, 1995). Thus, the iterative process involving practical knowledge and teacher knowledge is the key to teacher learning. In this sense, teacher learning within and across school networks is seen as a way of revitalizing personal and institutional growth. While the alignment of personal and institutional goals of teacher PD is the key to school improvement, the links between personal and institutional goals have to be galvanized by shared goals as well as a collaborative culture. This argument seems to suggest that PD efforts within an organizational level that is aligned and coordinated, as well as taking into consideration the school’s vision and goals, might be more fruitful. More empirical studies, however, are needed to ascertain the conditions of the context (e.g. school structures, teachers’ readiness and leadership) of PD for quality teacher learning.

Enactment of teacher PD: Enactment is a process in which teachers make sense of what they have learned from PD and how it can be contextualized in the classrooms. In the enactment process, teachers make educational decisions that require meeting certain criteria in the realm of the curriculum. But since not all criteria are stated explicitly, teachers must deduce, reflect, and elaborate when coming to a decision (Kansanen et al., 2000). Moreover, teachers are the original knowledge workers because teaching is ‘non-routine, ill-structured and creative’ (Tripp, 1993, p. 140), involving a number of different kinds of expert professional judgement (Frenkel et al., 1995). Hence, by looking into the extent to which teacher PD is able to regulate the enactment process that enables teachers to make educational decisions in the classrooms, researchers are able to understand not only teachers’ thinking trajectories and evolving practices, but also the tensions and challenges teachers face in the processes of ‘actualizing’ what they learn in their PD on a daily basis. For example, in a longitudinal study documenting the enactment process of PD, Bakkenes et al. (2010) found that teachers related the enactment process most frequently to ‘experimenting’ and ‘considering own practice’; ‘getting ideas from others’ and ‘experiencing friction’ were the next most frequently reported categories, followed by ‘struggling not to revert to old ways’ and ‘avoiding learning’ (p. 539). These findings could be explained by Day and Gu’s (2007) work on variations in the conditions for teachers’ professional learning and development, revealing that teachers with varied professional background differed in their learning trajectories, and thus there might be deviations in the enactment process.

One pertinent issue in the research on the enactment of teacher PD for sustained teaching and learning is the importance of facilitators’ roles (Remillard & Geist, 2002). In most cases, facilitators in teacher PD are the key position holders in the schools, such as principals, vice principals and heads of departments. In teacher PD, facilitators must be able to establish a professional learning community in which inquiry is valued and structure productive learning experiences for that community. They also must be able to use the school curriculum flexibly—reading the participants and the discourse, considering responses and possible consequences and taking responsive actions in order to balance the sometimes incompatible goals of the PD and the participants’ needs. Although these in-house facilitators might understand the goals of the PD and have access to the nuances of school context, it is unknown how teachers view facilitators’ double status of being agents who provide support to their professional learning as well as reporting officers who appraise their job performance in schools. A related issue to this is whether the quality of collaboration (among teachers and between teachers and facilitators), that is to inquire, learn and take action, both within and across the subjects/levels in the school, can be collegial and autonomous (Hairon & Dimmock, 2012). These issues are significant to research on teacher PD. As Guskey (2002) postulated, one of the reasons that teacher PD fail is due to the lack of understanding of the enactment process of PD by which change in teachers typically occurs. Hence, more investigation on this significant dimension of teacher PD is required in order to ascertain not only the benefits of teacher PD, but also uncover aspects which require appropriate inclusion, exclusion or refinements (Hairon et al., 2015).

Outcome of teacher PD: The outcome of teacher PD is frequently measured by teacher changes (Borko, 2004; Guskey, 1986, 2002) and student achievements (Hattie, 2003; Stronge, 2010), regardless of the fact that teacher change is a complex phenomenon and the debate on whether teacher change is a reason for or outcome of student achievements (see Guskey, 2002; Tan & Ponnusamy, 2014; Franke et al., 1998). The effectiveness of teacher PD has been documented by numerous researchers. From the findings of their review on teacher PD research, for example, Vescio et al. (2008) stated that teacher PD through professional learning communities (PLC) does have positive impact on teacher changes and student achievements, although the impact is primarily perceptive in nature. Also, in the context of community of practice (COP), teacher learning was found to occur through sharing, challenging and creating ideas about the thinking represented in students’ work. Teachers became better at elaborating the details of students’ reasoning and understanding students’ problem-solving strategies and began to develop instructional trajectories for helping students advance their thinking (Franke & Kazemi, 2001; Kezemi & Franke, 2004). On the other hand, despite the efforts in developing teachers’ capacity and expertise, for instance, in improving assessment, Scott et al. (2011) reported that confusion remained among teachers about terminology, principles and pragmatics, which undermined teachers’ confidence about making sound judgements about students’ work. Although teacher professional learning and development usually address teacher learning at the individual level, in the light of PD for school improvement, Newmann et al. (2000) argue that if professional development is to boost schoolwide student achievement, it should be expanded beyond the improvement of individual teachers to improvement of five aspects of school capacity: teachers’ knowledge, skills and dispositions; professional community; programme coherence; technical resources and principal leadership. Several scholars have discussed the purposes and effects of PD on teacher learning from the perspective of achieving the five aspects of school capacity (e.g. Grundy & Robison, 2004; Kennedy, 2005; Lieberman, 1996; Sachs, 2007).

A relevant issue related to the effectiveness of teacher PD on teacher changes is the constraints on teachers’ work when introducing innovation that expects teacher changes and that they apply the innovation directly to practice. Shulman and Carey (1984) suggest that teachers combine information received from teacher educators and researchers with what they already know, restructure it and make it fit into their perception of reality. They make different decisions after filtering new information through this reality rather than considering the information in isolation from their reality. Duffy and Roehler (1986) identified four kinds of constraints: curricular, instructional, milieu-related and organizational. They indicate that teachers have difficulties recasting traditional skills as strategies since they have routinized the procedures so much that they lack the flexibility to identify the mental operations associated with strategies and to be adaptive. In addition, teachers’ training did not prepare them for making curricular content explicit. The pressure to follow the codified curriculum, class sizes and grouping patterns are also part of the environmental constraints. Disruptions to the tight routines in school lead teachers to operate in a survival mode. Innovations which disrupt these routines are resisted. Consequently, there are at least four sets of ‘filters’ that constrain teacher decision-making: (1) teachers’ restructure of new information in terms of their conceptual understanding of curricular content, (2) teachers’ conception of instruction, (3) teachers’ perception of the demands of the working environment and (4) teachers’ desire to achieve a smooth-flowing school day. Hence, effectiveness is a complex idea that needs to be understood both in relation to teachers’ perceptions and how these vary over time in different institutional and personal contexts and in comparison with other teachers in similar contexts in terms of value-added pupil attainment (Day & Gu, 2007). Thus, each teacher makes decisions not on the basis of what the teacher educator or researcher said but on the basis of the restructured understanding of the innovations.

2.2 Characteristics and Operational Principles of Effective Teacher PD

The three fundamental dimensions of teacher PD have provided researchers the directions in their search for the characteristics and operational principles of effective PD programmes.

Characteristics of effective teacher learning: Through reviewing the work on teacher PD in the context of PLC, Bolam et al. (2005) summarized eight characteristics of effective teacher PD programmes/frameworks: (1) shared values and vision; (2) collective responsibility; (3) reflective professional inquiry; (4) collaboration; (5) individual and group learning; (6) mutual trust, respect and support among school staff; (7) whole-school, inclusive participation; and (8) out-of-school networks and partnerships (Bolam et al., 2005). These characteristics were also promoted by several scholars (e.g. Hord, 1997; Louis et al., 1996; McLaughlin & Talbert, 2001; Newmann et al., 1996). These characteristics highlight the significance of the establishment and maintenance of communication norms and trust that enable critical dialogues and collaborative interactions in the learning community (Borko, 2004; Grossman et al., 2001; Little, 2002). To promote these supportive yet challenging conversations and interactions, a collegial culture must be engendered (Borko, 2004; Frykholm, 1998; Seago, 2004). Teacher PD programmes with these characteristics provide teachers with (a) a deeper understanding of the subject-specific matter and how students think of and learn the subject matter; (b) ample opportunities to engage in exploration, reflection, and discussion; (c) activities that involve attending and responding to student thinking; and (d) contexts for collegial sharing, collaboration, and follow-up support during an extended period of time (Borko, 2004; Desimone, 2009; Garet et al., 2001; Sachs, 2007).

Operational principles supporting effective teacher learning: In their review, Bolam et al. (2005) identified four operational guidelines (processes) that support the eight characteristics of effective PLC including (1) encouraging shared leadership, (2) optimizing resources and structures, (3) facilitating individual and collective learning and (4) making explicit promotion of teacher learning communities. Hairon et al. (2015) considered these operational guidelines as context-embedded and observed that ‘context’ in the generic term can be divided into two sub-contexts—within and outside the school contexts. The sub-context of within the school includes factors such as school culture, structures (e.g. timetabling, organizational structure), leadership and resources. The sub-context of outside the school includes district/system factors such as district/system culture, leadership, resources and policies, and societal factors such as societal culture and national policies (Hairon et al., 2015). ‘Leadership’ within the school context, as argued extensively, does not exist only at the levels of principal, vice principal and heads of departments in the school. In teacher PD, concepts such as ‘shared leadership’ or ‘distributed leadership’ are representations of a different but more ‘healthy’ kind of leadership, inherently existing among teachers while they share, learn and collaborate in the learning communities or schools (Hairon et al., 2015; Hipp & Huffman, 2009, 2010; Huffman & Jacobson, 2003; Thomson et al., 2004).

3 Teacher Capacity and PD for the Twenty-First Century in Singapore

The Ministry of Education, Singapore (MOE), is committed to developing students’ twenty-first-century competencies and building up teachers’ professional capacity to deliver these competencies (MOE, 2010). The twenty-first-century competencies and desired student outcomes outlined by the MOE are shown in Fig. 13.1.

Twenty-first-century competencies and desired student outcomes (MOE, 2010)

The MOE recognizes the importance of teachers’ professional development on quality teaching and learning and has accordingly introduced the teacher growth model (TGM) (MOE, 2012). The model encourages Singapore teachers to be student-centric professionals who take ownership of their growth in understanding and delivering the twenty-first-century competencies. The model articulates the five desired learning outcomes of the twenty-first-century Singapore teachers as follows:

-

The ethical educator,

-

The competent professional,

-

The collaborative learner,

-

The transformational leader, and

-

The community builder.

The MOE’s endeavours to build up teacher capacity for the twenty-first-century competencies came along with the shift of teacher PD focus. In Singapore, the notion of ‘Thinking Schools Learning Nation’ (TSLN) marked the shift from a more ‘teacher-proof curriculum’ (Gopinathan & Deng, 2006) approach to one that ‘value(s) competencies which are built up through experience, practice, sharing and continual learning’ (Teo, 2001, p. 10). Since then, the emphasis on teacher professional learning and development has defined teaching to be ‘a learning profession, like any other knowledge-based profession of the future’ (Goh, 1997, p. 23). This rhetoric has led to the establishment of educational policies and organizational structures in the last decade both at the national and school levels that place great emphasis on promoting teacher professional learning and development.

At the national level, the emphasis on promoting teacher learning and development has manifested in the official status and sustained support given to PLC in the education system. PLC represents the education policy-makers’ intent to develop teaching professionals with self-initiative efforts to take on more active roles in collaborative professional learning to support school-based curricular development (Hairon & Dimmock, 2012). The historical development of PLC in Singapore can actually be traced back to 1998, when the teachers network (TN) was established as a unit within the training and development division (TDD) of the MOE (Tang, 2000; Tripp, 2004). The unit aimed to (1) formulate policies that support teacher professionals to move towards excellent practices through a network of professional sharing and learning and (2) serve as a catalyst for teacher-initiated PD through sharing, collaboration and reflection leading to self-mastery, excellent practices and fulfilment. It advocated a bottom-up approach to change as evidenced in its slogan ‘For Teachers, By Teachers’ (MOE, 2005). In 2000, The TN introduced a PD model named ‘Learning Circles’, in which teachers take the lead in engaging in collaborative learning using an action research framework to improve teaching and learning (Hairon et al., 2015). In 2010, the TN and the TDD were merged and renamed as the Academy of Singapore Teachers (AST). The AST retains the goal of teachers taking the lead in professional learning within the teaching fraternity and delivering high performance in teaching practice and student learning outcomes. To achieve that goal, the AST introduced the MOE-AST PLC model. The model borrowed Fullan’s ‘Triangle of Success (Fullan, 2003), which refers to ‘School Leadership’, ‘Systemness’ and ‘Deep Pedagogy’. To actualize the triangle of success, the idea of professional learning teams (PLTs) where groups of teachers engage in collective sharing and learning was developed to achieve ‘Deep Pedagogy’. In addition, the idea of coalition teams (CTs) where a group of school leaders (e.g. principal, vice principals) that represent ‘School Leadership’, was also adopted to provide conducive school structures and culture, and by doing so, achieve the ‘Systemness’. In this model, PLC is conceptualized as a whole-school initiative, in which groups of teachers collectively share and learn within PLTs. Teachers can have the option of choosing a range of collaborative learning tools, such as learning circles, action research and lesson study (Hairon et al., 2015).

Other than the policies and structures established at the national level, local schools are encouraged to adopt customized professional learning and development approaches with detailed implementation plans at the school level. In order to ‘create a culture of professional excellence which nurtures the individual and motivates all as a team to achieve superior performance’ (Teo, 2001, p. 6), schools are expected to become learning organizations where teachers and school leaders ‘constantly look out for new ideas and practices, and continuously refresh their own knowledge’ (Goh, 1997, p. 23). One influential consideration in the development of school-based teacher PD programmes, however, is that while educational policy-makers have ambitiously associated student learning outcomes with the twenty-first-century competencies in recent years, they expect the maintenance of high academic performance in view of ensuring the competitiveness and economic survivability of the small island nation in the global market. Therefore, Singapore schools are compelled to provide corresponding curricula that cater for a more diverse set of student outcomes, in both academic and non-academic domains (Dimmock & Goh, 2011).

4 The Exploratory PD Approach in SSS

4.1 The School-Based PD Framework and Guiding Principles

In line with TGM, Southern Star Secondary School (SSS, pseudonym) in Singapore has created a teaching and learning framework that identifies eight guiding principles of exemplary teaching and learning for academic and the twenty-first-century competencies. These principals include transfer of learning, thinking flexibly, quality assessment for/of learning, personalized learning, independent learners, safe and productive learning environment, effective communicators and effective collaborators. The framework and the guiding principles frame the ways teachers teach and the ways students learn in the school. The ultimate goal is to develop four student traits, including knowledgeable learner, independent and motivated learner, creative and critical thinker and effective communicator and collaborator. These traits are aligned with the twenty-first-century competencies.

4.2 The Structure, Cycles and Phases

Following the framework and the guiding principles, SSS initiated a series of PD cycles to situate and contextualize teacher learning in the school. Each PD cycle has a specific topic and follows a five-phase protocol that guides the teaching and learning practices throughout the whole cycle. The five phases are as follows:

-

Phase 1: Review literature, share findings and explore directions of practices

-

Phase 2: Explore and experiment through classroom practices and share small successes (e.g. lesson plans, methods and materials)

-

Phase 3: Review practices and confirm directions for implementation

-

Phase 4: Deepen and validate practices

-

Phase 5: Sustain practices.

According to the design, whole-school participation is required throughout the five phases of each PD cycle, with Phase 4 having additional external experts or consultants who are specialized in the topic of the cycle brought in for validation and evaluation purposes. Throughout the whole cycle, regular departmental discussions (focusing on making sense of theories, translating theories into classroom practices and doing reflections of new understandings and challenges) and whole-school professional learning sessions (focusing on cross-department sharings to keep all teaching staff posted of progress and to communicate strategic directions or actions to all departments) are incorporated into the school calendar.

According to the teaching and learning framework, each PD cycle is operationalized through the curriculum, assessment and pedagogy (CAP) committee. The CAP committee is a community of instructional leaders that consists of eight–ten members, including representatives of each subject department who are usually the most capable and experienced teachers in each department. The committee is chaired by the assistant director of instructional programme of the school and is tasked to cascade the vision of the planned PD cycle through instructional leaders who engage and motivate teachers in each subject area to translate the vision into practice. Teachers reciprocate by translating and enacting what they have learnt from the activities/sessions embedded in the five phases of the PD cycle into classroom teaching. Since 2010, SSS has actively engaged in three cycles of teacher PD. Each of the first two cycles spanned two years and had planned and strategized the processes for teaching and learning with the foci on quality assessment (2010–2011) and critical thinking (2012–2013). SSS is now in the midst of the third cycle with the focus on differentiated instruction and will complete the cycle by the end of 2016.

5 Potentials and Challenges

The key advantage of a school-based customized approach to teacher professional learning and development is that it considers authentic PD needs for the purpose of school improvement. Therefore, we anticipate that there is possibly a higher chance for school-based teacher PD approaches to embrace the key features of high-quality PD programmes highlighted by researchers working in different content areas (e.g. Borko, 2004; Desimone, 2009; Garet et al., 2001; Sachs, 2007). As far as SSS is concerned, the approach the school has taken reveals great potential to promote and sustain professional learning and development in the school.

First, the approach involves whole-school participation at different phases of exploring, designing, implementing and evaluating teaching and learning practices related to the specific topics of different PD cycles. In SSS, instead of engaging in fragmented PD activities, the school adopts topic-based PD cycles that are integrated across curriculum, instruction and assessment, involving the teachers, instruction leaders and key personnel of the school in the cycles. In addition, because of the whole-school participation throughout the different phases of the PD cycles, the approach seems likely to facilitate individual and group learning by creating ample opportunities for the teachers to engage in exploration, reflection and discussion and have critical dialogues and collaborative interactions. Also, the approach might help cultivate a collegial culture of sharing and learning in the school because of the deliberate design of having regular whole-school professional learning sessions that seek individual and departmental feedback and promote cross-department conversations.

Moreover, the PD approach seems to promote shared leadership among teachers by taking a bottom-up approach to improve teaching and learning practices in the specific context of the school. From the very beginning of each PD cycle (Phase 1), teachers are encouraged to explore different possibilities of translating the vision (the topic/focus of the specific PD cycle) into practice, rather than being given a set of prescribed guidelines that might be marginally relevant to their work and the context for them to duplicate in their classrooms. This design provides the teachers the space and opportunities to work on critical reflections of their existing knowledge and daily practices. Following the self-directed exploration, teachers are free to take initiatives and ‘experiment’ with their ideas in their classes. They are also given the platform (i.e. professional learning sessions) to share their ‘little successes’, concerns and struggles, respond to colleagues’ inquiries and offer their suggestions (Phase 2). The autonomy and agency given to the teachers are of great value in terms of promoting shared or distributed leadership in the school.

Furthermore, the approach provides the teachers with opportunities to connect with external resources and communities. At Phase 4 of each PD cycle, the school reaches out to experts or consultants through external networks and partnerships to help validate and evaluate the teaching and learning practices related to the topic of each PD cycle. Connecting with external resources and communities is valuable to school-based PD because a school has sometimes become too small a unit for PLC and schools need to become networked learning communities in order to connect to others and expand the fields of knowledge available (Jackson & Temperley, 2007).

Although the PD approach has shown potential to help SSS improve and sustain their teaching and learning practices, it also reveals challenges. Firstly, the composition of the CAP committee includes the former/current key position holders in the school (i.e. assistant director, heads of departments). This composition might not benefit the formation of collective responsibility as much as having teachers who are not in the management levels join the committee. One consideration could be to include experienced or long-serving teachers who are not in the management levels join the CAP committee. The inclusion of these teachers could be based on their knowledge and ability to model exemplary practices in line with the focus for each PD cycle. In addition, the implementation duration for each PD cycle is two years, which may be too short to complete an informative learning journey for teachers, considering the nature of the PD approach (continuing cycles), the required commitment to the activities in different phases and teachers’ workload in the school. Insufficient time given to teachers to ‘expand’ their knowledge during PD programmes could make teachers feel overwhelmed and result in teachers’ low self-efficacy in practising the requested tasks (Ertmer et al., 2014; McCormick & Ayes, 2009). More time may be needed for teachers to make sense of each topic selected for the PD cycle, translate and enact it in classrooms and enable sustained practices in the school. Particularly, for teachers teaching students who are in the final year of their secondary school education, pressure from exam preparations might deepen their concerns about getting too involved in the PD activities. Lastly, it is not clear how some other characteristics of effective PD programmes, including shared values, mutual trust, respect and support among school staff, are embedded or promoted in the PD approach. These characteristics, as argued, are also influential in the impact of PD programmes on teaching and learning.

6 Conclusion

The school-based PD approach taken by the SSS reveals potential to achieve its aim, although challenges also exist. The potential and challenges reported here are preliminary hunches after examining the proposed PD framework and its guiding principles. As part of on-going work, the dimensions of effective PD programmes and how they unfold in the school-based PD approach taken by the SSS need to be unpacked with evidences and nuances. With the school’s ambition to build up an entrenched culture for teacher PD through the approach, it would be useful to delve deeply into the PD cycles and the embedded phases of the approach to understand: (1) the intended conditions that facilitate (and hinder) teachers’ professional growth and teachers’ perceptions of these conditions; (2) the enacted process that informs the sustenance of practice and learning and (3) the achieved outcomes such as shifts in student achievements, quality of learning experiences and teachers’ readiness. Empirical studies on these three dimensions based on the approach in SSS would provide valuable findings for refinement and sustainability of teacher capacity building.

References

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10–20.

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., & Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learning and Instruction, 20, 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.09.001

Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Stoll, L., Thomas, S., Wallace, M., Greenwood, A., Hawkey, K., Ingram, M., Atkinson, A., & Smith, S. (2005). Creating and sustaining effective professional learning communities. Research Report No. 637. Department for Education and Skills.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3–15.

Bound, D., & Middleton, H. (2003). Learning from others at work: Communities of practice and informal learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 15(5), 194–202.

Campbell, A. (2011). Connecting inquiry and professional learning: Creating the conditions for authentic, sustained learning. In M. Mockler & J. Sachs (Eds.), Rethinking educational practice through reflexive inquiry (Vol. 7, pp. 139–151). Springer.

Campbell, E. (2012). Teacher agency in curriculum contexts. Curriculum Inquiry, 42(2), 183–190.

Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2007). Variations in the conditions for teachers’ professional learning and development: Sustaining commitment and effectiveness over a career. Oxford Review of Education, 33(4), 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980701450746

Dede, C. (2010). Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. In J. Bellanca & R. Brandt (Eds.), 21st century skills (pp. 51–76). Solution Tree Press.

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualisations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

Dimmock, C., & Goh, J. W. P. (2011). Transformative pedagogy, leadership and school organisation for the 21st century knowledge-based economy: The case of Singapore. School Leadership and Management, 31(3), 215–234.

Duffy, G., & Roebler, L. (1986). Constraints on teacher change. Journal of Teacher Education, 37(55), 55–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718603700112

Ertmer, P. A., Schlosser, S., Clase, K., & Adedokun, O. (2014). The grand challenge: Helping teachers learn/teach cutting-edge science via a PBL approach. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 8(1), 1–18.

Franke, M. L., Carpenter, T. P., Fennema, E., Ansell, E., & Behrend, J. (1998). Understanding teachers’ self-sustaining, generative change in the context of professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14(1), 67–80.

Franke, M. L., & Kazemi, E. (2001). Teaching as learning within a community of practice: Characterizing generative growth. In T. Wood, B. Nelson, & J. Warfield (Eds.), Beyond classical pedagogy in elementary mathematics: The nature of facilitative change (pp. 47–74). Erlbaum.

Frenkel, S., Korczynski, M., Donoghue, L., & Shire, K. (1995). Re-constituting work: Trends towards knowledge work and info-normative control. Work, Employment and Society, 9(4), 773–796.

Friedman, T. L. (2006). The world is flat: The globalized world in the twenty-first century. Penguin Books Ltd.

Frykholm, J. A. (1998). Beyond supervision: Learning to teach mathematics in community. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14, 305–322.

Fullan, M. (2003). Change forces with a vengeance. RoutledgeFalmer.

Garet, M., Porter, A., Desimone, L., Birman, B., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945.

Goh, C. T. (1997). Shaping our future: Thinking schools, learning nation. Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/1997/020697.htm

Gopinathan, S., & Deng, Z. (2006). Fostering school-based curriculum development in the context of new educational initiatives in Singapore. Planning and Changing, 37(1 & 2), 93–110.

Greeno, J. G. (2003). Situative research relevant to standards for school mathematics. In J. Kilpatrick, W. G. Martin, & D. Schifter (Eds.), A research companion to principles and standards for school mathematics. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Grossman, P. L., Weinburg, S., & Woolworth, S. (2001). Toward a theory of teacher community. Teachers College Record, 103, 942–1012.

Grundy, S., & Robison, J. (2004). Teacher professional development: Themes and trends in the recent Australian experience. In C. Day & J. Sachs (Eds.), International Handbook on the Continuing Professional Development of Teachers. Open University Press.

Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educaitonal Researcher, 15(5), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015005005

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8(3/4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

Hairon, S., & Dimmock, C. (2012). Singapore schools and professional learning communities: Teacher professional development and school leadership in an Asian hierarchical system. Educational Review, 64(4), 405–424.

Hairon, S., Goh, W. P., Chua, S. K., & Wang, L. Y. (2015). A research agenda for PLCs: Moving forward. Professional Development in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2015.1055861

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence? University of Auckland.

Hipp, K. K., & Huffman, J. B. (2010). Demystifying professional learning communities: School leadership at its best. Rowman and Littlefield Educational.

Hipp, K. K., & Huffman, J. B. (2009). Professional learning communities: Purposeful actions, positive results. Rowman and Littlefield.

Huffman, J. B., & Jacobson, A. L. (2003). Perceptions of professional learning communities. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 6(3), 239–250.

Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement. Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Jackson, D., & Temperley, J. (2007). From professional learning community to networked learning community. In L. Stoll & K. Seashore Louis (Eds.), Professional Learning Communities: Divergence, depth and dilemmas. Open University Press.

Kansanen, P., Tirri, K., Meri, M., Krokfors, L., Husu, J., & Jyrhämä, R. (2000). Teachers’ pedagogical thinking: Theoretical landscapes, practical challenges. Peter Lang Publishing Inc.

Kennedy, A. (2005). Models of continuing professional development: A framework for analysis. Journal of in-Service Education, 31(2), 235–250.

Kezemi, E., & Franke, M. L. (2004). Teacher learning in mathematics: Using student work to promote collective inquiry. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 7, 203–235.

Knowles, M. (1983). Adults are not grown up children as learners. Community Services Catalyst, 13(4), 4–8.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lieberman, A. (1996). Practices that support teacher development: Transforming conceptions of professional learning. In M. W. McLaughlin & I. Oberman (Eds.), Teacher learning: New policies, new practices (pp. 185–201). Teachers College Press.

Little, J. W. (2002). Locating learning in teachers’ communities of practice: Opening up problems of analysis in records of everyday practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(917–946).

Louis, K. S., Marks, H. M., & Kruse, S. (1996). Teachers’ professional community in restructuring schools. American Educational Research Journal, 33, 757–798.

Manen, M. v. (1995). On the epistemology of reflective practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 1(1), 33–50.

McCormick, J., & Ayes, P. L. (2009). Teacher self-efficacy and occupational stress. Journal of Educational Administration, 47(4), 463–476.

McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2001). Professional communities and the work of high school teaching. The University of Chicago Press.

Ministry of Education, Singapore. (2012, May 31). New model for teachers’ professional development launched. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/2012/05/31/address-by-mr-heng-swee-keat-a.php

Ministry of Education, Singapore. (2010, March 9). MOE to enhance learning of 21st Century competencies and strengthen Art, Music and Physical Education. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2010/03/moe-to-enhance-learning-of-21s.php

Ministry of Education, Singapore. (2005). Speech by Mr. Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Minister for Education, at the MOE Work Plan Seminar 2004, Ngee Ann Polytechnic Convention Centre, Thursday 22 September, 10:00 a.m. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/2005/sp20050922.htm

Mourshed, M., Chijioke, C., & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. Retrieved from www.mckinsey.com

Newmann, F. M., King, M. B., & Youngs, P. (2000). Professional development that addresses school capacity: Lessons from urban elementary schools. American Journal of Education, 108(4), 259–299.

Newmann, F. M., et al. (1996). Authentic achievement: Restructuring schools for intellectual quality. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Putnam, R. T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029001004

Remillard, J. T., & Geist, P. (2002). Supporting teachers’ professional learning through navigating openings in the curriculum. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 5(7), 7–34.

Sachs, J. (2007). Learning to improve or improving learning: The dilemma of teacher continuing professional development. Paper presented at the Keynote Address, ICSEI Annual Conference, Poderast, Slovenia.

Schon. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Towards a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey Bass.

Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Temple Smith.

Scott, S., Webber, C. F., Aitken, N., & Lupart, J. (2011). Developing teachers’ knowledge, beliefs, and expertise: Findings from the Alberta Student Assessment Study. The Education Forum, 75(2), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2011.552594

Seago, N. (2004). Using video as an object of inquiry for mathematics teaching and learning. In J. Brophy (Ed.), Using video in teacher education: Advances in research on teaching (Vol. 10, pp. 259–286). Elsevier, Ltd.

Shulman, L., & Carey, N. (1984). Psychology and the limitations of individual rationality: Implications for the study of reasoning and civility. Review of Educational Research, 54(4), 501–524.

Stronge, J. H. (2010). Effective teachers = student achievement: What the research says. Eye On Education Inc.

Tan, L. S., & Ponnusamy, L. D. (2014). Weaving and anchoring the arts into curriculum: The evolving curriculum processes. In C. H. Lum (Ed.), Contextualised practices on arts education: An international dialogue on Singapore arts education. Springer.

Tang, N. (2000). Teachers’ Network: A new approach in the professional development of teachers. ASCD Review, 9(3), 48–55.

Teo, C. H. (2001). A high quality teaching force for the future: Good teachers, capable leaders, dedicated specialists. Ministry of Education. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/2001/sp14042001.htm

Thompson, S. C., Gregg, L., & Niska, J. M. (2004). Professional learning communities, leadership, and student learning. Research in Middle Level Education Online, 28(1), 1–15.

Tripp, D. (2004). Teachers’ Network: A new approach to the professional development of teachers in Singapore. In C. Day & J. Sachs (Eds.), International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers (pp. 191–214). Open University Press.

Tripp, D. (1993). Critical incidents in teaching: The development of professional judgement. Routledge.

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80–91.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wang, J.LY., Tan, L.S., Lee, SS., Lim, N. (2022). An Exploratory Approach to Teacher Professional Development in a Secondary School in Singapore. In: Hung, D., Wu, L., Kwek, D. (eds) Diversifying Schools. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, vol 61. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6034-4_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6034-4_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-6033-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-6034-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)