Abstract

Since opening up to trade and investment in 1991, India has actively built economic ties with major powers and neighbours over recent decades with varying degrees of success.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since opening up to trade and investment in 1991, India has actively built economic ties with major powers and neighbours over recent decades with varying degrees of success. Yet Latin America was conspicuously absent due to vast geographical distance, a lack of cultural and linguistic linkages, few diaspora connections and the region’s relative unimportance in Indian trade diplomacy (Tharoor 2012; Desai 2015). However, this is gradually changing with increased trade between India and Latin America (Moreira 2010; ECLAC 2011; ADB, ADBI and IDB 2012). Specialization and trade have involved Indian final goods manufactures and information technology (IT) services in exchange for Latin American commodities. Indian hydrocarbon imports to Latin America also rose in the 2000s reflecting excess refining capacity in India (Bhojwani 2016). Nonetheless, it is unclear whether inter-regional trade has deepened into parts and components trade or global supply chain (GSC) trade which is vital for a sustainable economic partnership between the two.

This paper examines patterns of India-Latin AmericaFootnote 1 GSC trade and its links with national business environments, trade diplomacy and free trade agreements (FTAs). Using the so-called gross trade approach (see Constantinescu et al. 2015), it charts patterns of India-Latin American GSC trade by intermediate goods sectors and trading partners since 2000. This exercise reveals the impact of the global financial crisis on India-Latin America GSC trade and projects its value through to 2025. It then compares national business environments across countries (see Lall 1990; Dabla-Norris et al. 2013) to identify barriers to GSC trade between India and Latin America. Finally, it assesses efforts at trade diplomacy and FTAs.

2 Mapping Patterns of GSC Trade

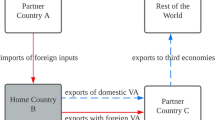

GSC trade is described as production networks, production fragmentation or global value chains, but essentially mean the same basic concept with subtle differences. It entails a sophisticated form of industrial organization which is different from a textbook idea of a single large vertically integrated factory in any one country.

It involves different production stages, such as design, assembly and marketing, across different countries, linked by a complex web of trade in intermediate inputs and final goods (Jones and Kierzkowski 1990). A lead company usually a multinational corporation coordinates the different production stages and trade.

For example, Toyota has sold 1.8 million units of the Toyota Prius (the world’s first mass-produced hybrid hatchback)—in the USA between 2000 and January 2017. The Prius for the US market was designed in Japan and is largely assembled there, but some parts and components are made in Southeast Asia and China. Parts and components trade occur between Japan and its Asian suppliers while Japan exports the Prius to the USA. Toyota coordinates final assembly, allocates work to various global suppliers, ensures that quality assurance and technical standards are met and undertakes expensive design and marketing activities. A recent empirical study has portrayed these complex intra-firm relations as “a barrel-shaped tier structure of the Toyota’s supply network, highlighting the fact that the previously hypothesized pyramidal structure is incorrect” (Kito et al. 2014, p. 20).

GSC trade has been interwoven with the globalization of trade and investment in the late twentieth century. As Baldwin and Lopez-Gonzales (2015) observe:

Internationalization of production has given rise to complex cross-border flows of goods, know-how, investment, services and people – call it supply-chain trade for short…Among economists, however, it is typically viewed as trade in goods that happens to be concentrated in parts and components. (Baldwin and Gonzales 2015, p. 1683)

Early signs of GSC activity were visible around the 1970s in the clothing and electronics industries. It has since penetrated many industries including other consumer goods, food processing, automotives, aircraft, and machinery. The role of services in GSC trade (e.g. engineering services, information technology services and professional services) is increasingly important but has been underestimated due to serious data problems.

The mainstay of empirical work on GSC trade by international economists has involved defining trade in parts and components using national trade data from the UN Comtrade Database (e.g. see Constantinescu et al. 2015). This so-called gross trade approach affords comprehensive, consistent and recent time series coverage of parts and components trade for nearly all countries in the world. More recently, with the development of similar international input–output tables for some countries, there has been growing interest in measuring trade in value added (e.g. WTO and IDE-JETRO 2011). Growth in the measured degree of imported input dependence between two points in time is interpreted as an indicator of GSC trade. However, input–output tables are either lacking or dated for several Latin American economies.

Accordingly, this paper applies the gross trade approach to examine trade in parts and components between India and Latin America. There is no unique method to decompose international trade data into parts and components and final assembled goods. An approximate way is to list specific items in which GSC imports are significantly concentrated and to use the total value of these items as an indicator of a country’s GSC trade. Based on Constantinescu et al. (2015), three import categories were selected: (i) parts and accessories of capital goods except transport equipment, (ii) parts and accessories of transport equipment and (iii) industrial supplies not elsewhere specified (processed). Constantinescu et al. (2015) report the total value of parts and components imports expressed as a ratio of total manufactured exports.

In interpreting the data, it is worth bearing in mind that the world economy seems to be recovering. The world economy grew at 3.1% in 2016 and is forecast to grow at 3.6% in 2017 and 3.7% in 2018 (IMF 2017). The main reason for the recovery is that successive shocks including the global financial crisis of 2007–2009 and the commodity price falls of 2014–2015 are abating. Many affected economies are experiencing cyclical recoveries. The IMF forecasts upward revisions to growth in the Euro area, Japan, Asia and Russia. India remains one of the world’s fastest-growing economies (with the IMF expecting growth of 7.4% in 2018) while Latin America is projected to transit from negative to positive growth. Global downside risks particularly political uncertainty and trade protectionism under President Trump’s “America First” nationalist approach could tilt the global outlook to the downside. India’s outlook could be dampened by the transitory effects of demonetization, the implementation of the goods and services tax (GST) and subdued private sector investment. Nonetheless, once these risks abate, one might reasonably expect world supply chain trade (including that between India and Latin America) to expand in the next few years.

Research using the gross trade approach shows that although India and Latin America had different historical involvement, their shares of world supply chain trade rose since the financial crisis. India is a latecomer and its share of world supply chain exports rose from 0.45 to 0.84% between 2001–2004 and 2009–2013 (Wignaraja 2016). Latin America was an earlier entrant and its share rose from 5.14 to 5.56% between the two sub-periods. Mexico dominates the regional figure with a share that increased from 3.82 to 4.10%. Meanwhile, Brazil’s share fell from 0.45% to 0.35%, Argentina’s rose from 0.09 to 0.22% and Chile’s stagnated at 0.01%. The share for the rest of Latin America increased from 0.77 to 0.88%.

India-Latin America GSC trade grew rapidly from a small base since 2000. Figure 1 shows the annual value of India’s total GSC imports and exports to Latin America (in current US$) from 2000 to 2016 with a projection to 2025. During 2000–2016, India’s GSC imports from Latin America (in current US dollar terms) grew at 20.4% per year while its GSC exports to Latin America grew at 15.7%. In 2016, the value of India’s GSC imports from Latin America was $3.1 billion (up from a miniscule US$ 157 million in 2000) while the value of its GSC exports to Latin America was $4.8 billion (up from $467 million in 2000). Accordingly, the value of India-Latin America GSC trade was nearly $8 billion in 2016 (or equivalent to 28.1% of total India-Latin America trade).

India’s GSC Trade with LAC (US$ Billion) GSC Global supply chain; LAC Latin American and the Caribbean Source Author’s calculations based on UN Comtrade Database. Accessed April 18, 2017. https://comtrade.un.org/data/. Note Projections for 2017–2025 were estimated using the Hodrick-Prescott filter in Eviews

India-Latin America GSC trade is conservatively projected to increase to $12.8 billion in 2025 (see Fig. 1). This projection consists of India’s GSC imports from Latin America of $4.5 billion and its GSC exports of $8.3 billion. The projections used the Hodrick-Prescott FilterFootnote 2 contained in the E-Views Econometrics Package. Many risks surround a long-term projection for GSC trade between India and Latin America and the positive outlook is likely to be tilted to the downside. There are several risks around an evolving new normal world economy and shifts in the global balance of economic power. Some of these include the imposition of trade restricting measures, macroeconomic policy uncertainty, sudden falls in growth and demand in India and Latin America, and disruptive technological changes (e.g. artificial intelligence and robotisation). If these risks are not effectively managed, the expansion of India-Latin America GSC trade may be pegged back.

The financial crisis had a limited impact on India-Latin America GSC trade. The emergence of GSC trade between India and Latin America was visible before the financial crisis. Such trade increased from $0.62 billion to $2.2 billion between 2000 and 2006. It doubled during the crisis to $4.1 billion in 2008 and doubled again after the crisis to $8.2 billion in 2014. It peaked at $8.7 billion in 2015 and fell in 2016.

Applying the proxy suggested by Constantinescu et al. (2015) confirms the rapid expansion of India-Latin America GSC trade despite a brief fall after the crisis. Figure 2 shows the ratio of India’s imported parts and components to manufactured exports with Latin America. The ratio increased in the years before the crisis—from 20.1 to 29.3% between 2000–2002 and 2004–2006—and was high during the crisis at 30.7% in 2007–2009. It then fell in the immediate aftermath of the crisis to 19.8% in 2010–2013 but soon recovered to previous levels of 30.0% in 2014–2016. Interestingly, this ratio peaked at 36.4% in 2015 and fell to 32.3% in 2016.

India’s Share of Imported Intermediate Goods to Manufacturing Exports with LAC (%). Source Author’s calculations based on UN Comtrade Database. Accessed April 18, 2017. https://comtrade.un.org/data/. Note Classification of intermediate goods, referred to as parts and components, is based on the concept used by Constantinescu, Mattoo, and Ruta (2015). Constantinescu et al. 2015. The Global Trade Slowdown: Cyclical or Structural? IMF Working Papers. No. WP/15/6. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Intermediate goods are defined as the sum of the following three BEC Categories: 1 industrial supplies not elsewhere specified, processed (BEC 22), processed; 2 parts and accessories of capital goods except transport equipment (BEC 42); and 3 parts and accessories of transport equipment (BEC 53). Manufacturing products is defined as the sum of SITC categories 5, 6, 7, and 8 (less 68)

India-Latin America GSC trade is characterized by commodity concentration. Figure 3 shows the shares of the three main categories in India-Latin America GSC trade for 2000–2002 and 2014–2016. The bulk of such trade occurs in industrial supplies and the pattern has been stable over the period. The share of industrial supplies in India’s GSC imports from Latin America rose significantly from 73.7 to 87.4% between 2000–2002 and 2004–2016 while the sector’s share in India’s GSC exports to Latin America rose from 76.5 to 78.4%. Meanwhile, transport equipment fell significantly in India’s GSC imports from Latin America from 16.4 to 4.3% and fell in India’s GSC exports from 17.0 to 14.0%. There is limited inter-regional trade in capital goods whose share of India’s GSC imports from Latin America fell from 9.9% to 8.3% while its share of India’s GSC exports from Latin America rose from 6.4 to 7.6%.

India’s GSC Trade with LAC by Commodity (%) GSC Global supply chain; LAC Latin American and the Caribbean Source Author’s calculations based on UN Comtrade Database. Accessed April 18, 2017. https://comtrade.un.org/data/

A few Latin America economies dominate GSC trade with India. Table 1 provides the shares of Latin American economies in GSC trade with India for 2000–2002 and 2014–2016. The rise of the Pacific Alliance and the decline of Mercosur are visible in GSC trade with India.Footnote 3 The share of the Pacific Alliance in India’s GSC imports rose significantly from 29.0 to 45.2% between 2000–2002 and 2014–2016 and its share of India’s GSC exports rose from 39.8 to 48.6%. Mercosur’s share of India’s GSC imports fell from 69.9% to 37.4% and its share of India’s GSC exports fell from 46.9% to 39.1%. Caricom and the rest of Latin America experienced a rise in their shares of India’s GSC imports and a decline in their shares of India’s GSC exports.Footnote 4

Seven Latin American economies dominate GSC trade with India. In spite of a large fall in its share of India’s GSC imports between 2000–2002 and 2014–2016, Brazil remains India’s largest GSC trader (with 29.4% of GSC imports and 29.7% GSC exports). Mexico is second with a rise in its share of India’s GSC exports over the same period. In 2014–2016, Mexico had 13.2% of India’s GSC imports and 26.4% of its GSC exports. Peru and Columbia come next with notable increases in GSC trade with India. In 2014–2016, Peru accounted for 13.1% of India’s GSC imports and 8.8% of its GSC exports while Columbia made up 11.4% of India’s GSC imports and 9.1% of its GSC exports. Other important Latin American GSC traders with India include Chile, Argentina and unexpectedly, Dominican Republic.

3 Assessing National Business Environments

Model-based studies indicate that economic gains can arise from trade liberalization and improving connectivity between India and Latin America (e.g. Mukhopaday et al. 2012). Many location-specific and policy factors influence firms to build the requisite manufacturing capabilities to participate in GSC trade (Kimura 2016). Numerous government regulations affect trade, logistics, business start-up, corporation tax and resolving disputes. Supply-side factors and markets matter including trade-related infrastructure, labour productivity, finance and institutions. Crime and corruption affect firms. Lall (1990) and Dabla-Norris et al. (2013) suggest that cross-country comparisons of national business environments provide valuable policy insights. ADB, ADBI and IDB (2012) and World Bank (2015) offer preliminary studies of barriers to Asia-Latin America trade. Drawing on this tradition, various indicators of the business environment in India and Latin America are compared to identify barriers to GSC trade between them. To keep the task manageable, these indicators are examined under four headings: (i) trade and investment regulations, (ii) behind-the-border regulations, (iii) trade infrastructure and logistics and (iv) labour productivity (see Table 2).

3.1 Trade and Investment Regulations

Open trade and investment regimes are the cornerstone for enhancing India-Latin America GSC trade. Low import barriers facilitate trade in parts and components, resource allocation according to comparative advantage and competition for firms to upgrade labour productivity and technological capabilities. As GSC trade is largely driven by multinationals, low barriers to trade and investment encourages inter-regional capital flows in GSC manufacturing activities, technology transfer and marketing linkages.

India’s import tariffs for manufactures have fallen since the mid-2000s and are on par with the average for Latin America. Between 2006 and 2016, India’s average tariffs for manufactures fell from 16.4% to 10.1% compared a reduction from 9.3% to 9.0 for Latin America. Three Pacific Alliance economies (Mexico, Peru and Columbia) experienced large tariff reductions to historically low levels of under 6% while Chile maintained low tariffs. In contrast, Mercosur’s largest economies—Argentina (from 12.6 to 14.2%) and Brazil (from 12.6 to 14.1%)—increased their tariffs well above Indian levels.

India’s FDI regime has improved since the mid-2000s but is less open to FDI than some Latin American economies. An FDI regulatory restrictiveness index is available from the OECD for 2006 and 2016. This tries to gauge the restrictiveness of a country’s FDI regulations by considering various restrictions: foreign equity limitations, approval mechanisms, restrictions on employing foreign labour, and operational restrictions (e.g. restrictions on capital repatriation). A high score on the FDI index indicates greater restrictiveness. However, the FDI index does not fully measure how FDI regulations are implemented and state ownership in key sectors are not captured. Furthermore, India is included but the FDI index only covers Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico for both years and Columbia, Costa Rica and Peru for 2016.

Keeping these qualifications in mind, India’s FDI index fell from 0.282 to 0.212 between 2006 and 2016. The average FDI index for the four Latin American economies, which fell from 0.0985 to 0.0955, indicates greater openness to FDI than India. Surprisingly, Mexico—the largest Pacific Alliance economy—is the most restrictive to FDI in Latin America. Mexico’s FDI index fell slightly from 0.211 to 0.193. Chile—another key Pacific Alliance economy—saw its FDI index falling from 0.063 to 0.057. The two large Mercosur economies had a rise in their FDI indices with Brazil’s from 0.095 to 0.101 and Argentina’s from 0.025 to 0.031. Meanwhile, the two smaller Pacific Alliance economies—Columbia and Peru—as well as Costa Rica are relatively open to FDI in 2016.

3.2 Behind-the-Border Regulations

Transparent, predictable and fair behind-the-border regulations help to create an environment with low transactions costs for India-Latin America GSC trade. It facilitates the entry of FDI into GSC manufacturing activities and domestic firms as competitive industrial suppliers. A key indicator of behind-the-border regulations is the number of licences and permits required to start a business and the time taken (in calendar days) which the World Bank provides for 2016.

Starting a business in India takes an average of 29 days to complete 13 procedures. This compares favourably with the Latin American average of 31.6 days to undertake eight procedures. Within Latin America, The Pacific Alliance economies are noteworthy for having streamlined business start-up procedures which are better than India. Chile (5.5 days for 7 procedures), Mexico (8.4 days for 8 procedures) and Columbia (9 days for 6 procedures) are stellar examples. Peru (26 days for 6 procedures), however, lags more efficient Pacific Alliance economies, takes a similar time to complete less start-up procedures than India. The Mercosur economies vary considerably in the efficiency of business start-up regulations. Uruguay seems the most efficient (6.5 days for 5 procedures) while in Venezuela it takes as much as 230 days for 20 procedures. Brazil seems to be tilted towards the less business-friendly end of spectrum, requiring 79.5 days to complete 11 procedures while Argentina takes 25 days to undertake 14 procedures.

3.3 Trade Infrastructure and Logistics

GSCs involve the dispersion of manufacturing activities over geographical space connected by trade in parts, components and services. Efficient and reliable infrastructure and logistics reduce the costs of undertaking GSC manufacturing and trade. However, the vast geographical distance between India and Latin America means lengthy supply chains which are susceptible to many barriers that can obstruct the easy movement of goods from one link in the chain to the next. Poor ports and airports, customs delays and weak logistics systems means barrier-related costs can be substantial and contribute to long lead times, high inventory costs, tying up working capital and cancelled orders.

Inter-country comparisons of the quality of trade infrastructure such as ports and airports are difficult due to measurement problems, statistical gaps, and the inherently subjective nature of such evaluations (ADB and ADBI 2009). The World Economic Forum provides one such evaluation for 2016–2017 based on a survey of global business leaders’ perceptions and hard data indicators. A value of 7 in the scoring system used shows the best possible situation and 1 the worst. There seems little difference between India (4.5) and Latin America (4.3) in the quality of airports. In terms of the quality of ports, however, India (4.4) fares quite well compared to the average for Latin America (3.9). Within the Pacific Alliance, Chile (4.9) and Mexico (4.4) have better ports than Colombia (3.7) and Peru (3.6). Meanwhile, the quality of ports in Mercosur appears to be a concern for business. Paraguay (4.5) and Argentina (3.8) fare better than Uruguay (3.1), Brazil (2.9), and Venezuela (2.7).

Similar problems beset inter-country comparisons of trade logistics. The World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index (LPI)—based on a worldwide survey of operators—indicates the efficiency with which goods can be moved into and inside a country. The LPI captures customs clearance, the quality of logistics services and the quality of infrastructure. A value of 5 shows high efficiency and 1 shows low efficiency. The data suggest although LPI scores have improved between 2007 and 2017, India’s (3.42) trade logistics seem more efficient than the average for Latin America (2.68). There seems to be a long tail of logistics under-performance in Latin America as even the best performers, Chile and Mexico, are below Indian levels.

3.4 Labour Productivity

Labour productivity growth and lower unit costs are key determinants of the competitiveness of firms in India-Latin America GSC trade. High labour productivity levels are associated with improvements in price, quality and delivery to world standards. However, measuring labour productivity is problematic and comparable cross-country data is lacking for developing countries. Fortunately, a crude measure—GDP per person employed (as a percentage of US levels)—is provided by the Canadian Conference Board Total Economy Database for India and key Latin American economies for 2015. Even after a decade or more of catching up, productivity levels in India and Latin America remain considerably lower than mature economies. In 2015, India’s output person was only 11% of the US level while the average for Latin America was 29%. Among Pacific Alliance economies, Chile (46%) has the highest output per person while Mexico (37%) is next. Columbia and Peru (both 23%) come some way behind. Argentina (42%) top’s Mercosur’s output per person league while Brazil (25%) and others lag.

4 Role of Trade Diplomacy and FTAs

After decades of lacklustre interest, signs of enhanced trade diplomacy between India and Latin America are emerging. There has been a flurry of visits by the Indian Prime Minister to Latin America. In July 2014, a month after his election, Prime Minister Modi participated in the BRICs Summit in Brazil. He met with several regional leaders and promised augmented Indian engagement with Latin America. In June 2016, after a thirty-year gap in Prime Ministerial visits, Modi visited Mexico to develop bilateral relations in trade, investment and technology. In 2018, Modi is scheduled to attend the G-20 Summit in Argentina.

Recent Indian diplomatic efforts reflect growing trade with a $5 trillion Latin American market, a bid to improve energy security (Brazil, Columbia, Mexico and Venezuela supply 20% of Indian crude oil imports) and a desire to compete with China’s significant economic presence in Latin America. Latin America’s aim to boost Indian ties is to lower overdependence on Chinese imports (which are viewed as harmful to local business) and the risks of the Trump administration’s trade protectionism. However, one of the main obstacles for greater Indian foreign investment in Latin America is financial. It is argued that India lacks the Chinese-level financial resources (both state and private sector) for overseas investment and is far more stringent on the bottom line (Bhojwani 2016). It is also argued that some Latin American countries fail to inspire the confidence of Indian investors due to strict land ownership regulations, high trade barriers, transport costs and poor internal connectivity.

Little FTA activity exists between India and Latin America (Wignaraja et al. 2015). But reflecting India’s greater interest in Latin America, attempts are being made to expand the coverage of goods trade in the two limited FTAs in effect. The India-Chile Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA)—in effect from August 2007—provided tariff concessions on a few tariff lines. India’s offer list was 178 tariff lines while Chile’s was 296 tariff lines. An expanded PTA was implemented in May 2017 with improved tariff concessions were provided by both sides to increase two-way goods trade. India’s offer list rose to 1031 tariff lines and Chile’s to 1798 tariff lines. Similarly, the June 2009 India-Mercosur PTA was limited to tariff concessions on 450 items. Talks began in January 2017 on an expanded PTA with the ambition of providing tariff concessions on 3000 items.

Recent efforts at trade diplomacy and FTAs are positive moves to foster India-Latin America GSC trade. The expanded India-Chile PTA and an eventual expanded India-Mercosur PTA will improve market access and two-way goods trade in commodities, processed food, engineering products and pharmaceuticals. However, murky non-tariff measures (NTMs) and key deep integration issues for upgrading GSC trade (such as investment, trade facilitation, intellectual property and services) are not tackled by these partial goods only agreements. An important next step is to include NTMs and deep integration issues into India’s agreements with Chile and Mercosur. Another is to initiate FTA negotiations with Mexico, which has become India’s largest trading GSC partner in Latin America and currently is a member of NAFTA. Furthermore, industry bodies and export promotion agencies should regularly disseminate information on business opportunities and tariff concessions to the private sector.

5 Conclusions

This paper studied patterns of India-Latin America GSC trade and its links with national business environments and trade diplomacy. It finds evidence of a changing trade pattern between India and Latin America. Historically, the trade pattern was based on Indian final goods manufactures and IT services in exchange for Latin American commodities. Recently, this trade pattern has begun to deepen towards GSC trade—entailing sophisticated production sharing over geographical space—which could lay the foundations for a sustainable economic partnership between India and Latin America.

The data indicate that India-Latin America GSC trade has grown rapidly from a small base to about $8 billion in 2016. While a further increase is projected to 2025, risks associated with a new normal world economy and domestic policy in India may tilt the positive outlook to the downside. Furthermore, issues exist in the commodity and country composition of intra-regional GSC trade. The bulk of such trade is occurring in industrial supplies and there is limited capital goods trade. Furthermore, a few larger Latin American economies dominate the region’s GSC trade with India. The Pacific Alliance is a rising player while Mercosur is on the decline and this difference seems to be linked to former’s more open trade and investment regimes.

Analysis of national business environments and trade diplomacy helps to identify barriers to India-Latin America GSC trade. Import tariffs have fallen to historically low levels in both India and Latin America. FDI restrictions have reduced but remain problematic in India, Brazil and Mexico. Business start-up procedures can be streamlined more in India and some Latin American economies. Logistics efficiency is a key problem in several Latin American economies. Labour productivity in India and, to a lesser extent, in Latin America remains below more mature economies. After conspicuous absence, trade diplomacy has picked up with increased contact between heads of state. This is gradually translating into expanded good trade coverage in the two limited inter-regional FTAs.

India-Latin America GSC is likely to remain a work in progress for some time. Further expansion can be supported by implementing domestic structural reforms aimed at barriers to FDI, business start-up, logistics and labour productivity. More focus in trade diplomacy on deepening FTAs and private sector engagement is also essential.

Notes

- 1.

This paper uses the term Latin America to cover 26 economies in Latin America and the Caribbean (see Table 1).

- 2.

It is a data smoothening technique commonly used in macroeconomics to remove short-term fluctuations that are associated with the business cycle, thereby revealing long-run trends. The use of the Hodrick-Prescott Filter presumes that deviation from potential trade is relatively short term and tends to be corrected fairly quickly.

- 3.

The Pacific Alliance consists of Chile, Columbia, Mexico and Peru. Mercosur’s members are Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela.

- 4.

Caricom’s share in India’s GSC imports rose from 0.2% to 0.3% between 2000 and 2016 while its shares in India’s GSC exports fell from 2.8% to 1.9%. The rest of Latin America’s share in India’s GSC imports rose from 0.9% to 17.2% while their share in India’s GSC exports fell from 10.5% to 10.4%.

References

ADB and ADBI. (2009). Infrastructure for a Seemless Asia. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute.

ADB, IDB and ADBI. (2012). Shaping the Future of the Asia and the Pacific-Latin America and the Caribbean Relationship. Manila, Washington DC and Tokyo: Asian Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and Asian Development Bank Institute.

Baldwin, R., & Gonzalez, J. V. (2015). Supply-chain trade: A portrait of global patterns and several testable hypotheses. The World Economy., 38(11), 1682–1721.

Bhojwani, D. (2016). Recalibrating Indo-Latin America policy. In R. Roett & G. Paz (Eds.), Latin America and the Asian Giants: Evolving ties with China and India, Washington. DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Constantinescu, C. Mattoo, A., & Ruta, M. (2015). The global trade slowdown: Cyclical or structural? IMF Working Papers. No. WP/15/6. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Dabla-Norris, E., Ho, G., Kochhar, K., Kyobe, A., & Tchaidze, R. (2013). Anchoring growth: The importance of productivity-enhancing reforms in emerging market and developing economies. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN13/08 December.

Desai. (2015, June 25). A new era for India-Latin America relations. Forbes.

ECLAC. (2011). India and Latin America and the Caribbean opportunities and challenges in trade and investment. Santiago: UN ECLAC.

IMF. (2017). World Economic Outlook, October 2017. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund.

Jones, R.W., & Kierzkowski. H. (1990). The role of services in production and international trade: A theoretical framework. In R. W Jones & A. O. Krueger (Eds.). The political economy of international trade: Essays in honour of R.E. Baldwin. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Kimura, F. (2016). Production networks in East Asia. In G. Wignaraja (Ed.), Production networks and enterprises in East Asia: Industry and firm-level analysis. Heidelberg and Tokyo: Springer.

Kito, T. Brintrup, A., New, S., & Reed-Tsochas. (2014). The Structure of the Toyota supply network: An empirical analysis. Said Business School Research Papers RP 2014-3. 1–23.

Lall, S. (1990). Building industrial competitiveness in developing countries. Paris: OECD.

Moreira, M. (2010). India: Latin America’s next big thing. Washington DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Mukhopaday, K. Thomassin, P. J., & Chakraborty, D. (2012, November). Economic impact of freer trade in Latin America and the Caribbean: A GTAP analysis. Latin American Journal of Economics, 49(2), 1–25.

Tharoor, S. (2012). India-Latin America relations: A work in progress Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 13(2), 69–74. (Summer/Fall).

Wignaraja, G. (2016). Introduction. In G. Wignaraja (Ed.), Production networks and enterprises in East Asia: Industry and firm-level analysis. Heidelberg and Tokyo: Springer.

Wignaraja, G., Ramizo, D., & Burmeister, L. (2015). Asia-Latin America FTAs: An instrument for interregional liberalization and integration? In A. Estevadeordal, M. Kawai, & G. Wignaraja (Eds.), New frontiers in Asia-Latin America Integration: Trade facilitation, production networks and FTAs. New Delhi and London: Sage Publications.

World Bank. (2015). Latin America and the rising South: Changing world, changing priorities. Washington DC: World Bank.

WTO and IDE-JETRO (World Trade Organization and Institute of Developing Economies-Japan External Trade Organization). (2011). Trade patterns and global value chains in East Asia: From trade in goods to trade in tasks. Geneva: WTO and IDE-JETRO.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wignaraja, G. (2020). Beyond Commodities: India-Latin America Supply Chain Trade. In: Raihan, S., De, P. (eds) Trade and Regional Integration in South Asia. South Asia Economic and Policy Studies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3932-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3932-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-3931-2

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-3932-9

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)