Abstract

This paper aims to show the trends and fluctuations of mean age at menarche from the 1880s to 1980s by using two kinds of menarche data collected by hospitals, volunteer organizations, private companies and so on: one is primary research data and the other are cited data in journals and books. Three findings emerge. (1) The long-term trend in the mean age at menarche was relatively stable at around the latter half of age 14 until the 1940s and afterward steadily declined to 12 years old in the 1980s. (2) The mean age at menarche showed a statistically significant decline even during the 1920s and 1930s in the case of students and mill workers; and (3) the velocity of height growth of both boys and girls was mostly increasing until the 1930s, and was at its maximum during the 1920s. These findings enable us to reconsider the conventional view of living standards and economic recession during the interwar period in Japan by analyzing not only economic but also anthropometric indices.

This chapter is a translation of an article that originally appeared in Shakai Keizai Shigaku 72(6) (March 2007), pp. 47–69.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The mean age at menarche is an important female anthropometric index. By showing a clear relationship between nutrition and the age of menarche in the context of monetary earnings in contemporary developing countries, it enables us to understand patterns of physiological growth of specific human sample populations (Knaul 2000). However, we have very few cases that clearly demonstrate the same relationship in the context of historical economies, excepting the case of slave economies (Steckel 2016). Menarche is fundamentally an outcome of individual hormone secretion and one of several physiological and physical changes of adolescence. Most girls are likely to remember their age at menarche because it was a dramatic event for them.

According to human physiological studies, the age at menarche usually comes about one year after the age at PHV, Peak-Height-growth-Velocity. In the area of historical research on the mean age at menarche, there are two typical types of research. The first is anecdotal history in which historians approach individual life courses based on individual growth data found, for example, in diaries in historical Europe (Komlos 1989a, Ch. 1. 1989b). The other is an analytical history mean age at menarche of sample populations based on an accumulation of as many sample cases as possible, like those undertaken regarding early twentieth-century Japan (Moriyama et al. 1980; Nakamura 1986). The difference between them in analytical method arises out of the difference in the historical materials available to historians. The research on Japan in particular, because it is based on statistical observations of the mean age at menarche, has focused on precise evaluations of the starting age of puberty beginning in the late nineteenth century. This paper uses the same method of collecting data as Nakamura and Moriyama, but differs from theirs in both the system and the content of the database.

Thus far, both in historical and development studies, historical demographers and economists have paid considerable attention to the mean age at menarche in order to estimate proximate determinants of human fertility (Bongaarts et al. 1983, Ch. 2; Frisch 2002; Tomobe 2002). These estimates appear to show, however, that the demographic impact of the later age at menarche can be quite small. At the same time, it seems clear the indices of SES-socioeconomic status, including household income, father’s occupation, parents’ education, family size, and so on contribute significantly to growth patterns including the age at menarche.

Additionally, many anthropometric historical studies have focused on the standard of living in various countries based mainly on data on height and weight of sample populations of males around age twenty (Komlos 1994, 1995, 1998a, b). Very few studies of anthropometric history focus on the physiological phase of female adolescent populations measured by the age at menarche. Careful research is needed on how wives and female children were treated in their households with a focus on certain of the harsh aspects of their lives because, given cultural systems of household formation such as the Japanese ie system, they likely occupied a position weaker than those of their husbands and male children.Footnote 1

This paper seeks to evaluate changes of biological standards of living in modern Japan by highlighting the changes in the mean age at menarche found in samples of Japanese girls researched between the 1870s and the 1980s. This evaluation leads to a reconsideration of the significance of Japan’s rural recession from the 1900s to just before the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s, and to a reassessment of the standard of living in Japan during the same period. In addition, this paper shows the shape and spurt velocity of height growth in Japan’s adolescent population using the statistical data compiled by the Ministry of Education in Japan (Mosk 1996). The first section of the paper shows the process of formulating the data on the mean age at menarche in modern Japan with reference to the new database created to undertake this. Based on these data, the second section shows changing patterns of the mean age at menarche by prefecture and occupation respectively. Finally, this paper presents some concluding remarks on the implications of the biological standard of living in Japan from the 1900s to the 1930s.

2 Research Framework

Both serial changes over time and cross-sectional differences in SES are crucial issues in research on the mean age at menarche. Several types of evidence indicate that SES is associated with delays in the age at menarche (Bongaarts et al. 1983, pp. 14–15; Scott and Duncan 2002, pp. 95–96).

-

(1)

In general, the mean ages at menarche in developing and developed countries differ by a few years.

-

(2)

A clear relationship between nutritional intake and the age at menarche appeared in a historical study of the United States. According to the study, well-nourished girls reached menarche 2 years earlier than undernourished ones.

-

(3)

In western societies with relatively reliable historical data, the age at menarche has declined by about 3 years since the end of the nineteenth century. This decline coincided with increases in body size and improvements in diet.

Although in many cases SES and the age at menarche are negatively correlated, what does the age at menarche as an anthropometric index suggest regarding the biological standard of living in historical populations? In considering this question, we need to think about the cultural condition and historical context of the places being analyzed for their historical standards of living. This paper evaluates the biological standard of living shared within Japan’s historical family households, the ie stem family system, in which the income and product of each household member was pooled and then redistributed to household members based on decisions about the capability and function of each member, with these roles remaining until the next successor to the household headship was decided on (Sen 1985).Footnote 2 As seen in Fig. 4.1, the rise in real wage rates usually led to an increase in pooled household income. This relationship, however, did not guarantee an increase in per capita nutritional intake within the household, especially for boys and girls. Because both boys and girls have increased appetite just before the age of their growth spurts (Frisch 2002, p. 26), their nutritional intake per capita contributed to the start of puberty.

The rise of total pooled household income probably led to a concomitant growth in both the functioning and the capability of the household (Sen 1985). However, the redistribution mechanism in the household did not operate evenly with regard to all family members. The age at menarche, because it is affected by nutritional intake during the period of adolescence, is a substantial indicator of the individual standard of living within households.

The issue of the redistribution mechanism within the household is especially important when we think about the historical standard of living in modern Japan. According to the historiography of interwar Japan’s economic history, historians have traditionally believed, though without robust quantitative evidence, that the Japanese economy stagnated during the interwar period. Because of the many political disturbances and uncontrolled military expansion of the time, the mass media highlighted and emphasized the dark recessionary quality of the social state of interwar Japan. More recently, however, economic history analyses of reliable quantitative data have shed light on aspects of a growing Japanese economy (e.g. Tomobe 2007, Ch. 6). In particular, the research on development of Japan’s labour markets from the 1900s to the 1940s, based on an Error–Correction–Model analysis, shows that: (1) the number of co-integrated local labour markets grew from the 1900s to the 1930s; and (2) the 1920s in particular showed both increasing real wages and growing market integration (Saito et al. 2004; Tomobe 2010, pp. 171–174).

At the same time, cultural or intellectual studies of interwar rural Japan lead to the same conclusion as the above labour market analysis. The 1920s and 1930s coincided with the period when, through the national movement of rural reform that had been launched around 1908, Japan’s peasants gained certain modern skills and information that contributed to a more comfortable ordinary rural life. Among the areas overlooked thus far by historians has been the social aspects that improved rural life, in which central and local governments and volunteers brought educational activities to peasants such as films explaining epidemic prevention and general hygiene (e.g. Yumoto 2000).Footnote 3 These activities surely contributed to a decline in the energy used to fight disease, unsanitary practices, and psychological anxiety. They thus contributed to a net increase of Japanese peasants’ nutritional status.

3 Data and Analysis

3.1 Structure and Variety of Sample Data

In Japan, at least, we have not until this point seen any official and continuous national statistics on the age at menarche. Rather, the Japanese government’s compilations of annual physical statistics were those measured at the physical examination for conscription (Chōhei kensa) performed by each branch of the military during the pre-war period. Accordingly, various types of research on the age at menarche in prewar Japan were undertaken independently by private companies and hospitals. For example, medical doctors or scientists conducted their research through questionnaires given to girls’ school students. Some obstetricians collected data through interviews of patients during medical examination. Their inquiries made it possible to learn about women’s body changes. Fortunately, though unofficial, these data were opened to the public through published papers that are available to us even now. For the present study, the papers containing research results from the 1880s forward on the age at menarche were collected to the extent possible. As a result, this study used 76 papers to build a database of the following items as found in each of the research papers (Tomobe 2007: list of samples in Japanese).

-

(1)

Mean age at menarche

-

(2)

Sample size

-

(3)

Research year

-

(4)

Place carrying out the research (prefecture)

-

(5)

Attributes of sample population

For a stricter analysis of changes in the mean age at menarche, we need not only the date and place of research but also the age distribution of the sample population. Only a few papers among the 76 meet this standard. In general, our samples found that some research was applied to all fifth grade students under the prewar junior high school system while others surveyed all married women admitted to hospitals as patients. Most of our samples, fortunately, had a stable age distribution of women aged 12–15. Two types of data appeared in the research papers: primary data collected by the researchers themselves, and cited data researched by others. The present paper collected both types of data as they appeared in the 76 research papers.

Table 4.1 shows the research year, the publication year, and whether the type of data collected was primary or cited data. As seen in Table 4.1, the first research year was 1871 and the last was 1987. Therefore, the number of samples amounts to 558 in all. All samples include information on research year, publication year and research place (prefecture).

Let us examine the samples cited in this paper. Table 4.2 shows the availability of primary data and of cited data. The total number of samples in the group is 558. Consequently, we see from Table 4.2 that 404 samples have information on sample size, and 154 samples do not. As this table indicates, the samples published before 1928 include information on sample size. From 1929 to 1959, most of the samples without information on sample size were cited data.

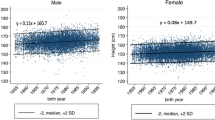

3.2 Trends and Fluctuations of Mean Age at Menarche

Based Mean Age at Menarche on the 558 samples that appear in Tables 4.1 and 4.2, Fig. 4.2 shows the secular trends and fluctuations of the mean age at menarche of all samples, while Fig. 4.3 shows the fluctuations by category of sample such as students, workers, and pregnant women. With some scattering of data points, Fig. 4.2 shows an overall trend toward decline of the mean age at menarche as the years approach the present day. In Fig. 4.3, both “Students” and “Unknown and Others” show a similar trend. On the other hand, “Mill-girls” and “Office Workers” show a more even distribution from age 14–17, rather than a concentration in the younger age zone. The differences between these cases, though the sample sizes are small, suggest the possibility that the physical stress of labour puts something of a strain on women’s bodies and tends to raise the age at menarche. Further, the case of “Pregnant Women and Adult Females” show hardly any scattering from the 1880s to the 1960s. The mean age at menarche in this category seems almost stable. This is probably the result of inaccurate memories of the actual date of menarche.

To present a comprehensive view of the trends in the mean age of menarche, this figure is based only on those samples that include information on sample size, with each dot in Fig. 4.4a indicating the research outcome with sample size on the Y-axis and research year on the X-axis. Most of the studies done before 1920 have larger sample size and the number of research studies increases rapidly after 1920 with widening range of sample size. The sample size after WWII is larger than those of the prewar period, with some 1960 studies involving more than 100,000 people.

Figure 4.4b shows the regional distribution of samples with the sample size on the Y-axis and the prefectures on the X-axis. Clearly, many research studies were done in Tokyo (Prefecture No. 13). Research done in eastern Japan (Nos. 1–23) tends to have smaller sample sizes that done in western Japan (Nos. 24–47). This feature of the distribution makes it unsuitable for cross-sectional analysis. Instead, Fig. 4.5 presents calculations of the trend of arithmetic mean age at menarche of all the samples. First, it seems clear that the mean age at menarche fell after 1946. As the post-war Japanese economy recovered and grew, the nutritional status of Japanese women improved significantly. According to C. Mosk’s findings, calcium and fat consumption increased, contributing to the physical growth of Japanese people (Mosk 1996, Ch. 5).

At first glance, the pre-WWII trend seems constant. Some smaller fluctuations, however, can be seen even in the prewar period. Note the downward trend from 1923 to 1942. This downward trend and the postwar decline can be interpreted as part of a continuous process. In other words, although there was a slight rise during 1942–46 due to worsening conditions during wartime, age at menarche had already started declining from the early 1920s. Table 4.3 summarizes the basic statistics on average age at menarche calculated from our samples to give a clear view of the trends. Surprisingly, the average age at menarche from the 1870s to 1940s had been very stable, fluctuating around the latter half of age 14. The transitional period of the 1950s and 1960s shows a rapid decline of mean age but a much larger S.D. Thereafter, the mean age declined until the latter half of age 12 with only a very small S.D., meaning that the age at menarche in Japan shifted into a long-term stage of lower stability, or stability at a lower age. Related to the main purpose of the paper, the statistics during the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s show comparatively stable changes in the decline of mean age. They seem in consonance with the normal process of declining mean age at menarche rather than indications of severe economic recession.

Before confirming the reliability of the statistical outcomes, let us examine three hypotheses of the physiologies affecting menarche: (1) marginal height, (2) marginal weight, (3) marginal proportion of skinfold thickness. This paper supports the third hypothesis, marginal thickness, based on Rose Frisch’s research on the relationship between height and weight (Frisch 2002, Ch. 6). First, by using the Nōson Hoken Eisei Chōsa [Rural health and hygiene research] published in 1929, which was based on early 1920s rural surveys that contained precise information of height and weight in Taishō-era rural Japan, we can test the Frisch method and the validity of applying her hypothesis to samples from rural Japan at that time.

Table 4.4 shows the evidence of the validity of the Frisch hypothesis. The figures in Table 4.4 show weights corresponding to each percentile of rural girls who have already experienced menarche. For example, in the age 14–15 category, which is very close to our sample’s statistical mean age at menarche, the 50th percentile weight of model 1 is 38.5 kg and the 75th percentile is 41.7 kg. Because the real average weight in Taishō-era rural Japan was 39.6 kg, model 1 fits the Frisch hypothesis. Likewise model 1 fits the hypothesis to a much greater degree than model 2 does. the degree of fitting of model 1 is much better than that of the model 2. The mean age at menarche calculated from our sample is very close to the real one expected from the Frisch hypothesis.

Table 4.5 shows the result of regression of mean age at menarche by the categories seen in Fig. 4.3.Footnote 4 Case 1 in Table 4.4 of all samples from the 1920s to the 1930s shows a negative correlation with a significance level of 1%. The case of mill workers from the 1920s to the 1950s has the same level of statistical significance while the case of students from the 1920s to the 1930s shows the same trend with slightly lower significance, but the case of students in the 1940s sample shows the opposite trend with a higher significance level.Footnote 5 The difference in results between workers and students probably comes from the gap in ordinary diet: workers ate much more at the company dormitory than students did at home.

3.3 Short-term Analysis of Mean Age at Menarche and Height Velocity

We can use the intersection of menarche data and height data to understand why a decline set in from the early 1920s.Footnote 6 Figure 4.6 shows the change of mean height of female from age 7–15 during the period up to 1930. Mean heights were clearly increasing in all age categories. The upward tendencies of girls age 12–15 are especially remarkable. This feature without doubt arose from the improvement in living standards of students at this time. Schoolteachers probably recognized that 12-year-old girls at the annual graduation ceremony were becoming taller year by year. This general improvement in girls’ anthropometric growth as seen in their height unquestionably led to a decline in the age at menarche beginning in the early 1920s.

Next, looking closely at the upward tendency of heights, we considered three stages in the period of changing trends: 1903–1910, 1911–1920, and 1921–1930. For each period, we calculated the velocities of heights. The analysis of velocity of female height growth enables us to understand when the decline of the mean age at menarche started. We define the velocity of height growth as following, in a formula that shows the index of the difference of mean heights at each age.

Table 4.6 summarizes the results of calculations of growth velocity. First, regarding the gender gap of velocity, before 1920 female velocity was surprisingly much better than male velocity, with fewer negative signs on the female side. Thereafter, until the 1930s, the values of boys’ height velocity rose a little more as a whole than those of girls, with signs becoming positive in all cases. In the 1940s, when Japan was at war, negative values of growth velocity appeared again in the case of both boys and girls like those of the 1900s. The growth velocity of height clearly was faster during the 1920s not only on the boys’ side but also on the girls’. The steady improvement in the body growth of girls, as seen from the remarkable height growth of the 1920s, signifies that the decline of menarche age started from this period. As far as the height and menarche data presented here indicate, socio-economic conditions during the interwar period were not necessarily deteriorating. Rather the data here is synchronized with the rise in real wages of carpenters observed in the same period (Saito et al. 2004).

4 Concluding Remarks

First, this paper collected data of mean age at menarche from many kinds of medical and sociological journal articles published from the 1870s to the 1980s by using an original database system, and carefully classified the data to analyze the trends and fluctuations of mean age at menarche in Japan.Footnote 7 Second, in order to confirm the results of this analysis of mean age at menarche, this paper evaluated the growth spurt of height during adolescence, especially from the 1900s to the 1930s, based on the height data compiled by Japan’s Ministry of Education. We present the following concluding remarks:

-

(1)

The long-term fluctuations of mean age at menarche in modern Japan show that until the 1940s the mean age was much more stable at around the latter half of aged 14. After that time, it declined to the middle of age 13 in the 1960s and then fell drastically to the latter half of age 12 by 1980. The background of these changes was Japan’s experience of WWII, the chaotic period of war of post-war recovery, and then of the age of high economic growth from the 1960s. It is undoubtedly the case that the hardship of wartime caused the age at menarche to rise due to the psychological stress on adolescent girls. Returning to a calmer social state, especially after 1970, the range of fluctuation of the mean age at menarche seems so small that we call it a period stability at a lower age.

-

(2)

Our data statistically confirmed that the tendency in the mean age at menarche in the case of students and mill girls was a clear decline from 1920. The Frisch hypothesis that marginal skinfold thickness affects the start of puberty and in Japan’s case in this period, schoolchildren growing up in their households had more accumulated skinfold fat thickness due to their rising nutritional status, causing puberty to start earlier. At the same time, not only psychological stress but also declining nutritional status delayed the onset of puberty during the war. The conventional wisdom regarding Japan’s family household system says that schoolchildren were placed in a weaker position in their households for the redistribution of nutritional intake. Many Japanese historians have hitherto stressed the weaker positions of those who sometimes played leading role in anecdotal accounts of severe economic recession during the interwar period. Certain factory workers, urban female servants (jochū), and migrant workers were surely among the leading players in the second stage of Japan’s industrialisation from the 1900s to the 1930s. At the same time because most of them came from rural peasant households, we may conclude that the general standard of living in rural Japan was not as bad as has been thought. Rather, at least by the early twentieth century, peasants’ living standards had already improved.

-

(3)

In the results of the height velocity analysis, both boys and girls at certain ages show negative velocity until the 1900s, but then, by the 1930s, the velocity has turned positive in all cases. It is especially noteworthy that both boys and girls generally experienced their prewar maximum height velocity during the 1920s.

-

(4)

Both the contours and the velocity of female height growth by age also have slopes that after age 12 seem remarkably steep compared with those before age 12 (Fig. 4.6). This suggests that the spurt had already begun to accelerate during the 1910s and 1920s. That is, it is very reasonable to think that the energy for initiating the spurt was already stored from an earlier period.

The changes in living standards of schoolchildren indicated by these analyses of age at menarche and height velocity have greater importance for socio-economic history when considered as part of the long-term process of demographic improvement in Japan since the middle of the nineteenth-century. The historical demography of Japan shows a substantial and drastic change in Japan’s fertility between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Table 4.7 is especially impressive in showing the great transformation of regional fertility patterns in Japan: in the lower-fertility east, the M index of late Tokugawa Japan rose rapidly to exceed Western values at least by 1925. As for the annual increasing rate of population growth, we see the same phenomena more drastically indicating a shift such that eastern Japan outstripped western Japan in regional population growth.

Throughout the entire Tokugawa period, the northeastern part of Japan called Tohoku typified a recessionary Tokugawa economy. Impoverished Tōhoku peasants intentionally and frequently performed mabiki, or infanticide, and datai, or stillbirths (Tomobe 2001). Probably, when even they faced the introduction of rural industry during the early nineteenth century, what had in the past been a severe condition of hunger drastically changed. Fertility rose as eastern Japan’s peasants, including those in Tōhoku, steadily accumulated wealth by working more intensively in both agriculture and proto-industry and changed their nutritional status and living standards. Here the new demographic-economic regime started to reach the modern state of a stable trend in age at menarche, as shown in this paper. Indeed, the data suggest a reassessment of the economic and social recession of Japan’s interwar period, and a reconsideration of whether the description of the age as deeply recessionary makes sense in light of such anthropometric evidence as height and age at menarche. Just recently, detailed research on schoolchildren’s heights in a rural part of southern Nagano prefecture in the 1920s and 1930s shed new light on the important role of rural Industrialisation in the improvement of child health and anthropometrics (Tomobe 2017). Synchronized with the fluctuations of age at menarche and height, one of the indices of living standards, namely infant mortality, in this case in Osaka city workers’ households, is seen to have declined drastically from the latter half of 1920s on. Living standards rose due to workers’ practices as well as support by city government, private companies and volunteer social capital (Higami and Tomobe 2012, 2014). Moreover, the bargaining power of tenant farmers against landowners was increasing significantly during the same period. As a result, landowners were giving up their landownership in the landlord-tenant relationship of pre-war Japan (Tomobe 2007, Ch. 6). Not only economic evidence but also anthropometric indices such as height and age at menarche without question shed light on the new insights necessary to a reconsideration of the condition of Japan’s living standards during the interwar period.

Notes

- 1.

We need to test the hypothesis in its specific historical context. For example, it is believed that the Japanese household formation system (ie) had a very skewed system of distributing food between males and females, but recently several historical studies have tried to test the primary status of eldest male children in the rural Japanese ie system.

- 2.

To think properly of the standard of living shared in the economies of early modern Japan’s peasant households, we must bear in mind that household members were engaged in various earning activities based on gender and age divisions of labor, including cultivation, by-employment, and casual labor. When the next household head was decided upon, other household members in principal left the household.

- 3.

Recently, many social historians of Japan have started working on this issue. For example, a local Eisei-kai [Hygiene Society] in Nagano Prefecture offered important activities from the 1900s to the 1940s, including (1) screenings and discussions of hygiene films, (2) simple education/skills for midwifery, (3) epidemic/local disease prevention, (4) distribution of pamphlets on hygiene and so on.

- 4.

Regressions based on time tend to yield larger t-values because more values on the Y-axis overlap on the same value of the X-axis.

- 5.

Most of menarche data used in the paper cannot be classified by birth cohort because they contain information only on the year the research was conducted. This means that the data on students are more reliable in terms of the precision of age at menarche age than the data in other categories, because student age is much closer to the age at menarche.

- 6.

The reason we chose height here is that, for physiological reasons, menarche frequently happens within a few years after the age of Peak Height Velocity.

- 7.

This careful treatment of data does not necessarily eliminate certain problems in menarche data that result from people’s inability to recollect accurately their age at menarche.

References

Bongaarts, John, and R.C. Potter. 1983. Fertility, Biology, and Behavior: An Analysis of the Proximate Determinants. New York: Academic Press.

Frisch, R.E. 2002. Female Fertility and the Body Fat Connection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Higami, Emiko, and Ken’ichi Tomobe. 2012. Infant Mortality and Beriberi in the City of Osaka between the Wars: The Impact of Changes of Mother’s Nutritional Condition on Infant Health. In Environmental History in East Asia: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Ts’ui-jung Liu, 259–272. New York: Routledge.

Higami, Emiko, and Ken’ichi Tomobe. 2014. How the Infant Mortality was reduced in the Early-Twentieth Century Osaka. Sociological Study 4(5): 446–460.

Knaul, Felicia Marie. 2000. Health, Nutrition, and Wages: Age at Menarche and Earnings in Mexico. In Wealth from Health: Linking Social Investments to Earnings in Latin America, eds. William D. Savedoff, and T. Paul Schultz, 35–70. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Kobayashi, K., and Y. Tsubouchi. 1979. Recent Trends and Regional Variations in Japanese Marital Fertility. In Fertility Transition of the East Asian Populations, eds. Lee-Jay Cho, and K. Kobayashi, 49–80. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii.

Komlos, John, and Joerg Baten (eds.). 1998. The Biological Standard of Living in Comparative Perspective. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Komlos, John, and Timothy Cuff (eds.). 1998. Classics in Anthropometric History. St. Katharinen: Scripta Mercaturae Verlag.

Komolos, John (ed.). 1994. Stature, Living Standards, and Economic Development: Essays in Anthropometric History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Komolos, John (ed.). 1995. The Biological Standard of Living in Europe and America, 1700–1900: Studies in Anthropometric History. Variorum: Aldershot.

Komolos, John. 1989a. Nutrition and Economic Development in the Eighteen-century Habsburg Monarchy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Komolos, John. 1989b. The Age at Menarche in Vienna: The Relationship between Nutrition and Fertility. Historical Methods 22(4): 158–163.

Moriyama, M., H. Kashiwazaki, and T. Suzuki. 1980. A Secular Trend in Age at Menarche in Japan. Minzoku Eisei (Ethnic Hygiene) 46(1): 22–32.

Mosk, Carl. 1996. Making Health Work: Human Growth in Modern Japan. Berkley: University of California Press.

Naimushō Eiseikyoku. 1929/90. Nōson Hoken Eisei Jicchi Chōsa. (Rural Health and Hygiene Research). Tokyo: Fuji Publishing Company.

Nakamura, I., M. Shimura, K. Nonaka, and T. Miura. 1986. Changes of Recollected Menarcheal Age and Month among Women in Tokyo over a Period of 90 Years. Annales of Human Biology 13(6): 547–54.

Saito, Osamu. 1988. Jinkō Hendō ni okeru Higashi to Nishi (Population Changes in Eastern and Western Japan). In Bakumatsu Meiji no Nihon Keizai (The Japanese Economy during Bakumatsu and Meiji Periods), ed. K. Odaka et al., 29–48. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Shinbunsha.

Saito, K., K. Tomobe, and T. Hirayama. 2004. Market Integration and Standard of Livings in Modern Japan: 1899–1939. Paper presented at the Fifth World Congress of Cliometrics, July 8–10, Venice, Italy, KEIO-GSEC Project on Frontier CRONOS Working Paper Series, No. 03-022.

Scott, Susan, and Christopher J. Duncan. 2002. Demography and nutrition: evidence from historical and contemporary populations. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Sen, Amartya. 1985. Commodities and capabilities. London: Elsevier.

Steckel, Richard H. 2016. Slave heights. In The Oxford handbook of economics and human biology, eds. John Komlos and Inas R. Kelly, 210–225, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Tomobe, Ken’ichi. 1991. Kinsei Nihon Nōson ni okeru Shizen Shussei-ryoku Suikei no Kokoromi (Estimates of Natural Fertility in Rural Tokugawa Japan). Jinkōgaku Kenkyū (The Journal of Population Studies) 14: 35–48.

Tomobe, Ken’ichi. 2001. The Level of Fertility in Tokugawa and Meiji Japan, c. 1800s–1930s: A Preliminary Analysis of the Hutterite Indices. In Asian Population History, eds. Ts’ui-jung Liu et al., 138–151, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tomobe, Ken’ichi. 2002. Tokugawa Nōson ni okeru Shussei-ryoku to sono Kinsetsu Yoin ni tsuite (The Fertility and its Proximate Determinants in Tokugawa Rural Japan). In Kindai Ikōki no Jinkō to Rekishi (Population and History of the Transitional Period toward the Modern Japan), ed. A. Hayami, 199–228, Tokyo: Minerva Shobō.

Tomobe, Ken’ichi. 2007. Zen-kōgyōka-ki Nihon no Nōka Keizai: Shutai-kinkō to Shijō Keizai (Peasant Household Economies in pre-industrial Japan: Subjective Equilibrium and Market Economy). Tokyo: Yūhikaku.

Tomobe, Ken’ichi. 2010. Kōgyōka to Shijō Tōgō (Industrialization and Market Integration). In Wākushoppu Shakai Keizai-shi (Workshop on Socio-Economic History), ed. O. Kawagoe et al., 171–174, Kyoto: Nakanishiya.

Tomobe, Ken’ichi. 2017. Height, Nutrition and the Side Production of Sericulture and Carp Feeding in Modern Rural Japan: The Case of Zakōji Village, Shimo-Ina Gun, Nagano Prefecture, 1880s–1930s. Paper presented at the Hitotsubashi Economics Seminar, 7 June, 2017.

Yumoto, Atsuko. 2000. Nagano-ken ni okeru Kindai Samba no Kakuritsu Katei no Kenkyū (Research on the Development of the Modern Midwife in Nagano Prefecture), MA thesis, Shinshū University, Japan. http://www.arsvi.com/2000/000300ya.htm.

Acknowledgements

Both the Grant-in-Aid for scientific research of “the anthropometric history of school boys and girls and its historical analysis of socio-economic factors in modern rural Japan”, (2016–2019, Hitotsubashi University, Ken’ichi Tomobe, No. 16K03775) and the Grant-in-Aid for scientific research of “Historical Changes in the Standard of Living and Socioeconomic Structures in Japan: Perspectives from Household Financial Diaries”, (2019–2022, Hitotsubashi University, Yukinobu Kitamura, No. 19H00593) offered financial support for this research. I would like to convey my special thanks to Dr. Tsutomu Hirayama of Shōnan Institute of Technology who contributed significantly to making the database and revising some of the complicated tables and figures used in this paper. Needless to say, all errors remaining in the paper are my responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Socio-Economic History Society, Japan

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tomobe, K. (2019). Changes in Female Height and Age of Menarche in Modern Japan, 1870s–1980s: Reconsideration of Living Standards During the Interwar Period. In: Okuda, N., Takai, T. (eds) Gender and Family in Japan. Monograph Series of the Socio-Economic History Society, Japan. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9909-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9909-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-9908-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-9909-1

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)