Abstract

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a key economic driver for both developing and advanced economies. Direct investments promote the transfer of technology and know-how, thereby increasing productivity. German industry, which is heavily export oriented and globally positioned, has always actively sought to invest in foreign markets and attract FDI. This is especially true with regard to China. For more than two decades, China has been a central destination for German FDI. Around the years 2014 and 2015, we witnessed the start of a new era of Chinese companies going global. Since then, Germany has become an important destination for Chinese FDI, mostly in the form of shareholdings or full acquisitions. But if this new era of Chinese outward FDI is to be as successful as the old one of German inward FDI, we need the right framework conditions—not least given political developments in China in recent years. The hope for an alignment of economic systems—the thesis of “change through trade”—has become a distant prospect. Indeed, we are already locked in systemic competition with China. That competition must be taken into account in the current debate on how we conduct our investment relationship with China in the future.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a key economic driver for both developing and advanced economies. Direct investments promote the transfer of technology and know-how, thereby increasing productivity. German industry, which is heavily export oriented and globally positioned, has always actively sought to invest in foreign markets and attract FDI. This is especially true with regard to China. For more than two decades, China has been a central destination for German FDI. Around the years 2014 and 2015, we witnessed the start of a new era of Chinese companies going global. Since then, Germany has become an important destination for Chinese FDI, mostly in the form of shareholdings or full acquisitions. But if this new era of Chinese outward FDI is to be as successful as the old one of German inward FDI, we need the right framework conditions—not least given political developments in China in recent years. The hope for an alignment of economic systems—the thesis of “change through trade”—has become a distant prospect. Indeed, we are already locked in systemic competition with China. That competition must be taken into account in the current debate on how we conduct our investment relationship with China in the future.

China’s economic rise has been one of the most important and impressive global economic developments in the past several decades. Since its economic opening and reform process at the end of the 1970s, China has become a popular investment destination for German companies, which from 1979 onwards were able to invest in some Chinese industrial sectors by forming joint ventures with Chinese partners. In 1987 the Chinese government allowed foreign investors to establish wholly owned subsidiaries in China, albeit, once again, in a limited number of sectors. Today German direct investment is largely concentrated in the automotive sector. Other sectors with significant German investments are the chemical industry, mechanical engineering and the electrical industry.

For the Chinese government, attracting FDI has always been a means of modernising industrial sectors through foreign technology, capital, management skills and expertise. From the outset, its policies towards FDI have been intended to guide investment into targeted industries while protecting strategic interests. Following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, other industries were opened up to foreign investment. It is indisputable that foreign investors have made a huge contribution to China’s economic development, especially since most FDI into China is greenfield and therefore has a much larger positive impact on job creation compared to mergers and acquisitions. These investments allowed for a massive transfer of technology and best practices, but also had spillover effects into the service sector and other industries. In exchange, China offered favourable production conditions, low labour costs and enormous domestic market prospects.

However, while the total stock of European FDI in China further increased, annual investment inflows from Europe to China have declined somewhat in recent years. During the period 2010–2015, annual European FDI in China was around €10 billion, but in 2016–2018 it fell to €8 billion. One of the reasons for that decline has been the more difficult economic environment: growth is still on a high level, but slowing, and wages are rising. Competition from Chinese companies is getting fiercer but business barriers for foreign companies still remain high. The sluggish progress of market reforms acts as another brake on investment growth. And China is still imposing significant market access restrictions on foreign companies.

Despite these challenges, China’s domestic market and its economic development continue to offer great potential for European investors. Among the reasons for us to remain optimistic are the high Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates (which remain far above those of most industrialised countries), China’s population of 1.4 billion and its growing middle class. Moreover, there are reasons to hope that China will further open its markets to foreign investors.

China Goes Global

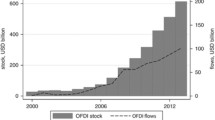

For a long time, investment flows between the European Union (EU)/Germany and China were largely a one-way street. Not much changed after the Chinese government unveiled its “going out” strategy in 2000. But meanwhile, after three decades of being primarily a recipient of FDI, China has emerged as a major FDI-originating country. It is no longer the case that Chinese investment in the EU is virtually non-existent, as was the situation until recently.

The last ten years especially have seen China’s financial reach rapidly extend beyond its borders. Today, many Chinese companies are investing and operating abroad. Beijing encourages Chinese enterprises, backed by China’s huge foreign exchange reserves, to acquire assets and expand business overseas. While Chinese outbound FDI was initially focused on natural resource extraction in developing economies, that focus has shifted in recent years to advanced economies, including the countries of the EU. The 2007–2011 financial and economic crisis yielded opportunities to acquire European companies at relatively low prices, and Chinese entrepreneurs were spurred to invest in the European market by the desire to secure a stronger foothold in the world’s second-largest consumer market, the strength of the European R&D landscape and the availability of highly skilled workers.

In the case of Germany, the quality guarantee “Made in Germany” and the country’s central geographical location in Europe certainly add to its attractiveness as an investment destination. When Chinese companies started to invest in Europe on a larger scale, investments from China were seen by most Germans as providing new impetus for development and promoting the opening of the Chinese market to German companies, some of which were struggling owing to structural problems and insufficient capital. That impression derived not least from German companies that had switched to Chinese ownership in the past, enjoying various advantages under their new owners, including employment guarantees, a long-term commitment to the location and improved access to the Chinese market. And besides the economic advantages, many in Germany had hoped at the time that increasing interconnectedness would lead to the convergence of economic systems.

Since the Chinese leadership transition in 2012, we have seen a change in the investment behaviour of Chinese investors. China’s “going out” strategy is itself undergoing major change: since industrial upgrade is one of President Xi Jinping’s top priorities, the focus of the “going out” strategy has shifted to the acquisition of foreign technology so that China can move up the industrial value chain. This national target is prominently laid out in the “Made in China 2025” strategy, which focuses on key industries Chinas planners believe will dominate the economic landscape of the future. In this context, Germany is a particularly popular investment destination, as it has many privately owned small- and medium-sized enterprises—“hidden champions”—which are attractive targets for Chinese companies seeking technology leadership. In recent years, there have been share purchases in companies such as EEW Energy from Waste (Beijing Enterprises), KrausMaffei (ChemChina) and Bilfinger SE Wassertechnik (Chengdu Techcent Environment Group), as well as the takeover of the banking house Hauck & Aufhäuser by the conglomerate Fosun. Acquisitions or purchases of further shares in recent years include industry leaders Putzmeister by Sany and KION (45 per cent share) by Weichai Power.

Still a Win-Win Situation?

While initially most Germans were well inclined towards Chinese direct investments, a debate has since emerged over whether the impact of Chinese investments in Germany is mainly positive or negative. That debate was fueled in 2016 by the announced plans of the Chinese company Midea to take over the German robot manufacturer KUKA. Since then, concerns have grown that Germany could lose competitiveness in key industries by selling enterprises to China. At the same time, warnings have been sounded that the functioning of market mechanisms could be weakened—since Chinese investors are both willing and able to pay prices that do not reflect market prices as they are estimated by Western companies. This fact also raises questions about “unfair doping” in the form of state help.

Moreover, fears were expressed at the time of the planned KUKA takeover that the German government did not have sufficient administrative instruments to control risks arising from acquisitions by Chinese companies. In mid-July 2017 the German government amended the Foreign Trade and Payment Ordinance (AWV) to expand the list of economic sectors in which takeovers are subject to approval and to extend the review period. This was followed by another amendment in December 2018 lowering the bar for a screening in some instances to a share of 10 per cent. Thus, for reasons of national security, it can now block FDI not only in the German defence industry but also in “critical infrastructure”. On the EU level a joint action by three countries pushed forward the issue. In February 2017 Germany, France and Italy sent a letter to the EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström requesting for the adoption of political measures aimed at greater reciprocity between EU member and non-member countries in market access for FDI and access to procurement markets. This initiative set in motion a process that was finalised two years later, in Spring 2019, with the adoption of a new regulation on state control of foreign investment by the European Parliament. In essence this new regulation is a step in the right direction. It meets two central requirements of the German industry. Firstly, interventions may only be made to protect national security and secondly, the decision on investment bans remains in the power of the member states. This will help curb the politicisation of investment controls.

The Federation of German Industries’ (BDI, Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie) position on foreign investment is clear: Foreign investors—including those from China—are welcome in Germany and the EU. Their investments create wealth and jobs. The fundamental freedom of investment must be maintained in the EU. Property rights and freedom of contract must also be guaranteed and strengthened as fundamental pillars of the liberal and social market economy in Germany. Deviations from these principles may only occur in a few clearly defined areas. The “protection of public order and security”, as regulated in the Foreign Trade and Payments Law (AWG) and the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance, is a generally accepted criterion for state intervention in investment decisions. A problem, however, is the worldwide trend that governments are increasingly expanding the concept of national security in order to limit “access” of foreign investors to technologies deemed worthy of protection. Therefore, the investment audit mechanism anchored in German foreign trade law should continue to be strictly limited and exclude any economic factors. Apart from issues of national security, the BDI and its members share concerns which include possible distortions of competition through state-subsidised takeovers. In order to prevent distortions of competition on the takeover market, adjustments should instead be made to competition law, not foreign trade law. EU competition instruments do not, or only to a very limited extent, address market-distorting practices or target state support brought into the EU internal market from outside. This is currently putting our businesses at a competitive disadvantage. The BDI therefore calls for a stronger use of competition policy in order to ensure a level-playing field in investment.

On the other hand, China could do its part by ensuring more transparency with regard to financing conditions, corporate accounting standards and ownership structures. That would narrow the gap and go a long way towards restoring acceptance of Chinese investments in Europe.

Chinese Investors: Different from Most Others

That said, China is making it difficult for us to apply a light-touch regulatory approach towards Chinese investments. While governments should intervene in private investment decisions on economic grounds only when markets are distorted—even some proponents of openness and minimal state intervention admit that market distortion is intolerable—we cannot but acknowledge that it is not always easy to determine whether an investor is playing by the rules. And this is particularly true for China, where ownership structures and funding sources are often non-transparent and the dividing line between the state and business is blurred. Moreover, the argument that “[w]e don’t want to become ‘Chinese’ by closing our own market to foreign investors” weighs heavily in the current debate.

Various aspects of both the Chinese economy and Chinese politics underscore that China is an investor unlike any other. This does not mean that we do not want investments from China in Europe. Nevertheless, we must be aware of those features that are peculiar to China and take them into account in the current discussion:

-

Asymmetries in market access: A huge challenge related to Chinese FDI is the lack of reciprocity. The European Union Chamber of Commerce in China had good reason to ask the following question in its 2017/2018 position paper on European business in China: “Does [China] support only one-way investment openness that allows its enterprises to go global while foreign business, sitting on China’s doorstep, is again told to be patient?” EU countries have largely open investment regimes, with few explicit restrictions on investment. Chinese companies face few, if any, limitations in investing in European industries such as automotive, construction, financial services, healthcare, insurance, logistics, media and telecommunications. By contrast, European companies in China continue to be either barred from participating in those industries or limited to holding a minority position. Free movement of capital is one of the “four freedoms” of the EU single market: it requires all EU member states to allow unhindered capital flows not only between member states but also from third countries into the EU market. For its part, Germany has traditionally adopted an open investment stance by offering foreign investors free market access and refraining from use of a general protection mechanism for key technologies. It offers complete freedom in terms of greenfield investments and has only a small number of restrictions on national security grounds with regard to mergers and acquisitions.

This is not the case in China. An index of market access restrictiveness compiled by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that China remains among those countries with the most restricted access for foreign investors. The Chinese government protects strategic industries from foreign access, which means that European businesses in China encounter numerous barriers—both formal and informal—of a political and legal nature. Entire Chinese sectors are closed to foreign investment and a number of industries are subject to joint venture coercion. China prohibits foreign investment in a number of sectors and severely restricts it in other areas. And it continues to do so despite having become a major advocate of globalisation and free trade in its rhetoric and repeatedly asserting that it wants to open up to foreign investors and will make the necessary changes.

In early 2017 China amended its “Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries”, which was launched in 1995 in order to “guide” FDI into Chinese industry. As a result of those amendments, the number of sectors restricted to foreign investment has been reduced from 93 to 63. However, that reduction was partially on paper only: in reality, just 18 sectors can be considered to have been removed from the catalogue’s “negative list” and opened up to some extent. The hopes of foreign companies were further fueled by the so-called State Council Document No. 5 or Circular No. 5 (Notice on Several Measures on Promoting Further Openness and Active Utilisation of Foreign Investment), which was released at the beginning of 2017. That document outlines three policy goals: (1) take further steps to open up to the outside world, (2) further create an environment of fair competition, and (3) further strengthen efforts to attract foreign investment. In 2018, China announced several rounds of tariff cuts. Most prominently, it lowered import tariffs to 15 per cent on autos and components, from 25 per cent for passenger cars and 20 per cent on trucks, followed by further cuts on import taxes covering more than 700 goods. The cuts mainly targeted products which China regarded as benefiting the own economy or lowering costs for domestic consumers. Beyond that, China presented its long announced “negative list” for foreign investment, eventually replacing the former “Catalogue for the Guidance of Foreign Investment Industries” and reducing the number of restricted or forbidden sectors by 15 to 48. In another step, the National Development and Reform Commission published its first national negative list for investment, specifying 151 areas that are either banned to non-state businesses or require government approval for entry. Some of the mentioned steps were regarded as “window-dressing” or long overdue, but it also must be acknowledged, that they are a move in the right direction. The announcement of ending the joint venture constraint in the coming years for the production of cars, aircrafts and ships is one such positive example. Some German car makers have already taken the opportunity to extend their share with their Chinese Joint Venture Partners of up to 75 per cent. Nonetheless, there are still too many restrictions on investment as well as high tariffs and non-tariff barriers in place. Some argue, that without the pressure of a looming trade war with the United States, China wouldn’t have been so quick in implementing these measures, and in China voices were heard that outside pressure on reforms would strengthen the position of the liberal and market-oriented groups within the Chinese authorities. In 2019, the new Foreign Direct Investment Law could be the next big step in favor of foreign companies, depending on how it will be enforced in practice. According to the draft, government officials will be prohibited from using administrative means to force foreign businesses to transfer their technology and foreign investors could enjoy equal treatment with domestic counterparts, with the exception of sectors specified in the government’s negative list. As promising as those policy goals sound, German industry would welcome faster and more decisive implementation. The asymmetry in openness was tolerable as long as investments flowed mainly in one direction, but since China has become the second-largest global investor after the United States and a technological powerhouse, it is no longer sustainable—neither politically nor economically.

-

Systemic competition and market distortion: The EU provides conditions for open, market-based international competition. China, on the other hand, is a “socialist market economy” in which the state enjoys extensive rights to intervene in the market. Informal interrelationships exist between the state and the economy in China and market distortions result from state ownership, state subsidies and other non-market economic features. State-owned enterprises have traditionally played a major role in the Chinese economy—a role that has grown not weaker but stronger in recent years—and today they are important investors abroad. It is true that, in general, it is very difficult to differentiate between state and private players in FDI; but this is especially the case in China, where even formal ownership structures often lack transparency. Chinese FDI continues to grow without any clear separation between the authorities and domestic commercial entities. That party cells are being established or revived in companies and joint ventures suggests that the Chinese state has no intention whatsoever of withdrawing from the economy. However, in the current debate about investment screening, China has spoken out strongly against any more state intervention in Europe.

-

Strategy for innovation: Investment is always closely linked to innovation. Ideally, investment encourages innovation. In Germany, the state promotes and supports applied research in industry based on the common belief that new technologies and new products are most efficiently developed and marketed by industry. All market participants are treated equally—regardless of whether they are German, European or non-European. Meanwhile, China, on the other hand, has drawn up a state innovation plan with clear targets aimed at promoting its high-tech sectors. In practice, substantial government research funds are available mainly to Chinese companies. Under its “Made in China 2025” strategy, which was introduced in 2015, China has developed a new long-term industrial strategy. The strategy identifies the high-tech industries in which it wants to compete internationally through its own companies. The aim is to achieve global leadership in various key technologies (including information technology, computer-controlled machines, industrial robots, energy-saving vehicles and medical devices) by 2049. China is moving up the global value chain and ridding itself of the image of the “cheap workbench of the world”; indeed, it is fast becoming a high-tech superpower and clearly sees technology acquisition through outward FDI as an important tool to expedite this process. This strategy is problematic—for two reasons. First, it is neither an effective nor a sustainable way to improve competitiveness and boost the innovative capacity of Chinese industry as a whole. A much more effective approach would be to create the right framework conditions for China’s domestic market. Second, it causes friction with China’s trading partners and hinders fair global competition, and may in the end lead to more state intervention on all sides—not least owing to the above-mentioned asymmetries in market access.

For decades, another integral part of China’s innovation strategy has been forced technology transfer—that is, granting market access in exchange for technology. This practice takes place via joint ventures, public tendering, certification practices and investment permits. German industry is very interested in an innovative and strong China, as our closest trade links are with other high-tech countries; accordingly, China’s development as a high-tech location promises to offer many opportunities. However, those opportunities will materialise only if foreign companies are given the same opportunities to participate as local companies. We need a level-playing field, a predictable regulatory framework and a free exchange of ideas and data. This last factor is particularly important, as digitisation will play an increasing role for our economies.

Minimise Risks, Maximise Opportunities

Given the enduring systemic differences between the EU’s open market economy and China’s “socialist market economy”, it is clear that the regulatory framework for our investment relations has to adequately address those differences in order to minimise the risks and maximise the opportunities. Systemic competition persists between the Chinese economy with its central planning and the Western market economy, in which economic planning is largely the responsibility of private enterprises. This competition can be won only with the help of the principles of our open market system. We cannot respond to Chinese central planning by dismantling the open market economy, which, based on the principles of private property and freedom of contract, is a much stronger mechanism for promoting innovation and discovering new knowledge than is central planning. Therefore, the protection of the open market system, rather than the protection of technologies, is key for Europe to remain competitive in the next decades. We must strengthen the basic market economic principles rather than weaken them. And for that reason, we must proceed carefully with expanding the scope of foreign investment screening.

We believe that the best way forward would be a comprehensive bilateral investment treaty between the EU and China that gives investors predictable, long-term access to the respective markets and protects both investors and their investments in those markets. Especially important, the treaty should ensure equal market access for German companies in China and for Chinese companies in the EU. German subsidiaries in China should enjoy the same entrepreneurial freedom of action as do Chinese domestic companies. Unfortunately, since their beginning in 2013, the treaty negotiations have yet to show fundamental progress. As the asymmetries in market access are a big disadvantage for European companies on the global competition landscape, our strong hope is that the negotiations will progress and come to a completion in the foreseeable future A clear concession from China towards opening its markets would send a powerful signal. Moreover, it would keep the new global wave of protectionism at bay and make it easier for those committed to an open investment regime in Europe.

References

Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI) (2017a), Requirements of a Bilateral Investment Treaty Between the EU and China; Berlin, August.

Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI) (2017b), Expanding the Scope of Foreign Investment Screenings of non-EU investors; Berlin, July.

Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI) (2019), China–Partner and Systemic Competitor. How Do We Deal With China’s State-Controlled Economy? Berlin.

European Union Chamber of Commerce in China (EUCCC) (2017), European Business in China, Position Paper 2017/2018, Beijing.

Hanemann, Thilo; Huotari, Mikko (2018), EU-China FDI: Working towards reciprocity in investment relations, MERICS Papers on China, Berlin.

Jungbluth, Cora (2016), Chance und Herausforderung. Chinesische Direktinvestitionen in Deutschland; Global Economic Dynamics Studie, Gütersloh, Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Strack, Friedolin (2017), Die Sicht der deutschen Industrie auf chinesische Hochtechnologie-Investitionen in Deutschland, Policy Brief, Bonn, Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kempf, D. (2019). Investment Relations with China: Never Easy but Always Worthwhile. In: Wenniges, T., Lohman, W. (eds) Chinese FDI in the EU and the US. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6071-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6071-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-6070-1

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-6071-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)