Abstract

Transcriptome analyses have revealed large numbers of non-protein coding transcripts called noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), which are produced from most genomic regions in mammalian cells. These ncRNAs include many thousands of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) more than 200 nucleotides in length. Although our knowledge of these lncRNAs remains limited, recent studies have revealed their diverse roles under physiological and pathological conditions, as well as their mechanisms of action in a variety of cellular processes including epigenetic regulation, transcriptional regulation, posttranscriptional processing, and intracellular organization. In addition, multiple studies show that aberrant expression of lncRNAs is associated with various diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders, suggesting that lncRNAs represent promising target molecules for biomedical applications. Here, I review lncRNAs and several related applications and in particular an emerging class of lncRNAs termed architectural RNA (arcRNA). I describe and discuss arcRNAs in mammals, focusing on their biogenesis, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. In addition, I highlight our newly established methods for discovering arcRNA candidates. Finally, I emphasize the importance of identifying the RNA elements embedded in lncRNAs that dictate their functions; these elements provide opportunities for future applications in biotechnology, biomarkers, and therapeutics.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Long noncoding RNA (lncRNA)

- Architectural RNA (arcRNA)

- Nuclear body

- Semi-extractable RNA (seRNA)

- NEAT1

- Satellite RNA

- SINEUP

- Prion-like domain

- Low-complexity domain

- Intrinsically disordered domain

11.1 Introduction

Only 2% of the human genome consists of protein-coding genes, and the rest of the genome was once considered “junk.” However, over the past decades, advances in sequencing technologies and analytical methods have led to the discovery of tens of thousands of RNAs that are pervasively transcribed from mammalian genomes but are apparently not translated into proteins (Bertone et al. 2004; Carninci et al. 2005; Kapranov et al. 2007). The subset of these RNAs greater than 200 nucleotides in length is collectively termed long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), many of which have been shown to have functions just as rRNA, tRNA, and snRNA do (Cech and Steitz 2014). Moreover, lncRNAs have been recognized as key regulatory molecules in gene expression programs (Guttman and Rinn 2012; Geisler and Coller 2013; Quinn and Chang 2016), and recent studies have identified lncRNAs that play critical roles in cellular function, development, and disease (Ponting et al. 2009; Rinn and Chang 2012; Schmitt and Chang 2016). Different types of lncRNAs, such as circRNA and sno-lncRNA, are generated by distinct processing mechanisms (Chen 2016b; Quinn and Chang 2016).

lncRNAs are expressed in a more tissue- and development-specific manner than mRNAs are, and this characteristic makes them suitable as biomarkers for diagnostic and therapeutic applications (Ulitsky and Bartel 2013). Although the vast majority of lncRNAs remain uncharacterized, a recent CRISPRi screen of 16,401 lncRNA loci (using the CRiNCL guide RNA library, available to academic users via Addgene) in seven human cell lines identified 499 lncRNAs that affect cell viability (Liu et al. 2017). Interestingly, most of them (89%) affected cell growth in only one of the seven cell lines, suggesting that lncRNA functions are cell type-specific and demonstrating that this method could be used as a platform to study these functions. These observations support the utility of lncRNAs for therapeutic applications.

One important feature of lncRNAs is that they carry positional information within the nucleus (Batista and Chang 2013; Engreitz et al. 2016b). By contrast, protein-coding RNAs lose such information after transcription because they are exported to the cytoplasm before translation. Consistent with this, lncRNAs regulate expression of nearby genes in cis (Engreitz et al. 2016a). In addition, lncRNAs have been proposed to act as spatial amplifiers that control gene expression and three-dimensional genome architecture (Engreitz et al. 2016b). lncRNAs function in several biological processes, including epigenetics, histone modification, locus-specific gene regulation, enhancers, chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and posttranscriptional regulation (Quinn and Chang 2016). Mechanistically, lncRNAs can act as guides, scaffolds, architectures, decoys, or enhancers (Guttman and Rinn 2012; Hirose et al. 2014a). For example, several lncRNAs act as chromatin regulators by recruiting and integrating chromatin regulatory proteins at specific chromatin sites (Rinn and Chang 2012).

In some cases, the specific RNA sequences themselves are not necessary; instead, the process of transcription itself at a specific locus is an important regulatory cue for the expression of nearby genes (Engreitz et al. 2016a; Paralkar et al. 2016). Notably, some RNAs annotated as lncRNAs are in fact translated to produce small polypeptides that are biologically active (Anderson et al. 2015; Nelson et al. 2016; Matsumoto et al. 2017). In skeletal and heart muscle cells, small peptides conserved among species are produced from lncRNAs and modulate the activities of membrane-bound proteins.

The functional characterization of lncRNAs is ongoing, and one of the next important challenges is to classify lncRNAs according to their functional RNA elements found in lncRNAs that are RNA sequences or structures for interactions with specific RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) (Hirose et al. 2014a) (Fig. 11.1). Understanding the RNA elements hidden in lncRNAs would open the door to new applications of lncRNAs, e.g., interference with specific functions of lncRNAs and engineering of artificial lncRNAs. Similar approaches using modular domains of RNAs and proteins have already been used to engineer ribozymes, RNPs, and proteins. Thus, identification and characterization of the modular domains of lncRNAs would expand the toolbox for a wide variety of experimental applications in molecular biology, biotechnology, and therapeutics.

A concept for modular RNA domains and RNA motifs in lncRNAs. lncRNAs are surrounded by numerous RBPs, some of which recognize specific RNA sequence or structural motifs. Some RBP binding sites and combinations of RBPs on the specific binding sites (e.g., dashed boxes) form functional modular RNA domains that play specific cellular functions

11.2 Examples of lncRNAs with Applications

Here, I summarize several examples of lncRNAs, along with potential applications, focusing on their modular RNA functional domains, biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and in vivo functions (Table 11.1).

The lncRNA called SINEUP (RNA containing SINE elements that UPregulate translation) is an antisense lncRNA that promotes translation of its target mRNAs (Takahashi and Carninci 2014; Zucchelli et al. 2015a). This class of lncRNAs was originally identified in mouse as an antisense transcript of the Uchl1 gene, AS Uchl1 (Carrieri et al. 2012). AS Uchl1 spans a 73 nt region overlapping the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and translational start site of the Uchl1 mRNA and promotes translation of UCHL1 protein without affecting mRNA stability. Outside the overlapping region, AS Uchl1 consists of inverted SINEB2 (short interspersed nuclear element B2) elements. Promotion of translation depends on the overlapping region, called the binding domain (BD), and an inverted SINEB2 element called the effector domain (ED) (Zucchelli et al. 2015b). By changing the sequence of the BD into the antisense sequence of another mRNA, synthetic SINEUPs can be designed that target a mRNA of interest and function in trans (Zucchelli et al. 2015a). These synthetic SINEUPs can promote translation in multiple species and cell types, including human, monkey, hamster, and mouse cells in vitro and mice in vivo (Zucchelli et al. 2015a; Indrieri et al. 2016; Zucchelli et al. 2016). In general, this approach yields protein upregulation from 1.5- to 3-fold. miniSINEUPs that exclusively contain the BD and ED (~250 nt in length) are also active, and these shorter sequences are easier to deliver by viral vectors, or as naked synthetic SINEUPs, for therapeutic use (Zucchelli et al. 2015a, b). Among the available methods for increasing protein production, SINEUPs have two advantages: (1) they increase protein production without introducing stable genomic changes and (2) induction is typically moderate and within the physiological range (~2-fold). These features make SINEUPs appropriate for use in research, protein manufacturing, and therapeutics (Zucchelli et al. 2015a, b). As an example of a therapeutic approach, some inborn diseases are caused by haploinsufficiency of the causative gene, and in such cases, synthetic SINEUPs could be used to upregulate the sole remaining wild-type allele. As SINEUP, another strategy has been developing to upregulate the gene expression based on the finding of natural antisense transcripts (NATs) (Wahlestedt 2013). NATs are transcribed in an antisense direction, in proximity to or overlapping with their sense mRNA partners, and usually repress the expression of the partner mRNAs. Therefore, inhibition of NATs can derepress their partner mRNAs (Katayama et al. 2005). Many overlapping NATs have been identified in human (Engström et al. 2006). Oligonucleotides targeting NATs, called antagoNATs, hold promise for therapeutic applications aimed at upregulating the expression of target mRNAs (Wahlestedt 2013).

Circular RNA (circRNA), another class of lncRNAs, is produced by back-splicing from pre-mRNAs (Chen 2016a; Salzman 2016). Because they cannot be targeted by exoribonucleases, circRNAs are generally quite stable. Thousands of circRNAs have been identified in several species, including human, mouse, and C. elegans. In functional terms, these RNAs act as molecular sponges for miRNAs and RBPs. For example, CDR1as sequesters miR-7, and circMBL sequesters RBP MBNL (Hansen et al. 2013; Memczak et al. 2013; Ashwal-Fluss et al. 2014). The sequences and structures of circRNAs are critical for this sequestration. Accordingly, understanding the rules underlying these interactions would lead to novel applications of circRNA for specific sequestration of RNAs and RBPs of interest. Over the course of efforts to understand the biogenesis of circRNA, systems have been developed for expression of circRNAs in cells, thus expanding their potential usage (Liang and Wilusz 2014). In addition to the noncoding features of circRNAs, they have recently been shown to be translated into proteins. For example, Circ-ZNF609 is a circRNA that can be translated into a protein with a function in myogenesis (Legnini et al. 2017). Furthermore, circRNAs are abundant in specific conditions and cell types, suggesting that they might be suitable as biomarkers or therapeutic targets (Chen 2016a). Moreover, fusion-circRNAs generated from oncogenic translocation contribute to cancer cell survival and oncogenic potential in vivo (Guarnerio et al. 2016).

lncRNAs such as HOTAIR and UPAT regulate the degradation of specific proteins. HOTAIR plays roles in target gene repression and cancer-induced ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis by providing scaffolding for E3 ubiquitin ligases such as Dzip3 and Mex3b and ubiquitination substrates such as Ataxin-1 and Snurportin-1 (Yoon et al. 2013). These E3 ligases and substrates associate with specific RNA domains of HOTAIR, suggesting its potential application in targeted degradation. On the other hand, UPAT lncRNA prevents proteolysis of epigenetic factor UHRF1 by blocking its association with the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-TrCP (Taniue et al. 2016). The specific RNA domains on UPAT responsible for its binding to partner proteins have not yet been identified.

1/2-sbsRNA (half STAU1-binding site) promotes the degradation of target mRNAs via STAU1-mediated mRNA decay (SMD) by providing binding sites for STAU1, an RBP that binds double-stranded RNAs (Gong and Maquato 2011). 1/2-sbsRNA forms imperfect base pairs with target mRNAs. In contrast to 1/2-sbsRNA, TINCR lncRNA directly associates with STAU1 and interacts with its target mRNAs via the 25 nt TINCR box motif, which is enriched in its target sequences (Kretz et al. 2013).

Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs), which are transcribed from enhancers, are important determinants for cell lineages (Kaikkonen et al. 2013). Consequently, inhibition of eRNAs influences specific genes in specific cell lineages, leading to the idea of “enhancer therapy.” Many lncRNAs play crucial roles in epigenetic regulation. XIST lncRNA is one of the most extensively studied lncRNAs, and its RNA domains and interacting proteins have been identified (Chu et al. 2015; McHugh et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2016). In addition, lncRNAs play major roles in cancer biology. Multiple lncRNAs, including PVT1, CCAT2, PCAT-1, SAMMSON, MALAT1, and NEAT1, are associated with cancer progression and repression (Schmitt and Chang 2016). For example, NORAD sequesters PUMILIO2 proteins in the cytoplasm and plays a critical role in genome stability (Lee et al. 2016). Therefore, elucidation of the in vivo cancer-related functions of lncRNAs could lead to therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

11.3 Architectural RNAs (arcRNAs) and Their Potential Applications

In this section, I will focus on architectural RNAs (arcRNAs), a class of lncRNAs that serve as architectural components of nuclear bodies, i.e., cellular bodies within the nucleus. Eukaryotic cells compartmentalize cellular materials to organize and promote essential cellular functions. Cells possess two types of compartments: cellular organelles, which are surrounded by lipid bilayers, and membraneless organelles, also known as cellular bodies (Courchaine et al. 2016; Banani et al. 2017). The latter compartments, which are typically composed of specific sets of proteins and RNAs, are fundamental cellular compartments required for specific biochemical reactions, RNP assembly, storage of proteins and RNAs, and sequestration of proteins and nucleic acids. Numerous cellular bodies have been identified to date, including the nucleolus, perinucleolar compartment, nuclear speckles, paraspeckle, Cajal body, gems, PML body, histone locus body, Sam68 nuclear body, stress granules, and P-bodies. Typically, cellular bodies exchange their constituents dynamically. Recent work showed that phase separation between distinct material states (i.e., liquid, hydrogel, and solid) is a key mechanism underlying the formation of these compartments (Wu 2013; Alberti and Hyman 2016; Banani et al. 2017). Proteins containing prion-like domains (PLDs) or low-complexity domains (LCDs), which are unstructured and prone to aggregate, play essential roles in the formation of phase-separated cellular bodies (Aguzzi and Altmeyer 2016; Uversky 2016).

Although many cellular bodies are proteinaceous, some nuclear bodies have RNAs as their architectural cores (Chujo et al. 2016). This concept was originally proposed based on the identification of NEAT1 (nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1), a nuclear-retained lncRNA that is an essential component of the paraspeckle, a nuclear body (Clemson et al. 2009; Sasaki et al. 2009; Sunwoo et al. 2009). In addition to NEAT1, other lncRNAs play similar architectural roles in the construction of nuclear bodies in various species, suggesting that this is a general function of lncRNAs. For example, heat shock RNA (hsr) omega is the lncRNA for the omega speckle in Drosophila melanogaster, and meiRNA is the lncRNA for the Mei2 dot in S. pombe (Chujo et al. 2016). Accordingly, we refer to such RNAs as architectural RNAs (arcRNAs) (Chujo et al. 2016). An arcRNA can be defined as a lncRNA that localizes in a specific nuclear body and is essential for its integrity. In this section, I focus on the arcRNAs in mammals and describe the known arcRNAs, focusing on their biogenesis, biological functions, relationship to diseases, and potential applications (Table 11.2).

11.3.1 NEAT1 lncRNA

Several groups identified NEAT1 lncRNA as an essential architectural component of the paraspeckle, which was originally identified as a distinct nuclear body localized adjacent to nuclear speckles (Clemson et al. 2009; Sasaki et al. 2009; Sunwoo et al. 2009). The paraspeckle is a massive (~360 nm diameter), highly ordered RNP structure comprising more than 60 kinds of proteins, several of which are required for paraspeckle biogenesis (Souquere et al. 2010; Naganuma et al. 2012; Fong et al. 2013; Yamazaki and Hirose 2015). The DBHS (Drosophila melanogaster behavior human splicing) family of proteins, SFPQ, NONO, and PSPC1, have coiled-coil structures that form homo- or heterodimers; two of these, SFPQ and NONO, are essential for expression of NEAT1 and formation of paraspeckles (Sasaki et al. 2009; Naganuma et al. 2012; Passon et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2015). In addition, several paraspeckle proteins, including FUS, DAZAP1, HNRNPH3, and the SWI/SNF complex components BRG1 and BRM, are essential for paraspeckle integrity (Naganuma et al. 2012; Kawaguchi et al. 2015). Many paraspeckle proteins are RBPs with a PLD or LCD, some of which are essential for paraspeckle formation (Naganuma et al. 2012; Yamazaki and Hirose 2015). In addition, the PLDs of FUS and RBM14 are essential for paraspeckle integrity (Hennig et al. 2015).

The NEAT1 gene is located on chromosome 11q13 in human and chromosome 19qA in mouse. In both species, the gene encoding another abundant nuclear lncRNA, MALAT1, is adjacent to NEAT1. The NEAT1 lncRNA has two isoforms, NEAT1_1 (~3.7 kb) and NEAT1_2 (~22.7 kb), which are produced from the same transcription start site under the control of the same promoter and then subjected to alternative 3′-end processing (Naganuma et al. 2012). The NEAT1_1 lncRNA has a poly(A) tail, whereas NEAT1_2 has a unique triple-helix structure at its 3′ end that stabilizes cognate RNAs (Wilusz et al. 2012). Similar cis-acting RNA structures, some of which are called ENE (element for nuclear expression), are found in MALAT1 lncRNA, genomic RNAs of diverse viruses including Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, and ~200 transposable element RNAs in plants and fungi (Conrad and Steitz 2005; Brown et al. 2012; Tycowski et al. 2012; Wilusz et al. 2012; Tycowski et al. 2016). In addition to its role in the stabilization of RNAs, the triple-helix structure increases their translation rates (Wilusz et al. 2012). An important role in 3′-end processing of NEAT1_2 is played by a tRNA-like structure, located just after the triple-helix structure, that is required for 3′-end cleavage of the NEAT1_2 transcript (Wilusz et al. 2008). This tRNA-like structure is processed by RNase P, which is involved in tRNA maturation.

Importantly, the long isoform NEAT1_2 is essential for paraspeckle formation, whereas the short isoform NEAT1_1 is dispensable (Naganuma et al. 2012). RNA polymerase II inhibition rapidly disrupts the paraspeckle, suggesting that paraspeckles form co-transcriptionally and are highly dynamic in nature (Fox et al. 2002). This idea is supported by the direct observation of de novo formation of the paraspeckle during transcription of the NEAT1 locus (Mao et al. 2011). An elegant electron microscopic study demonstrated that NEAT1 is spatially organized within paraspeckles (Souquere et al. 2010). Specifically, the 5′ and 3′ ends of NEAT1_2 are located on the periphery of the paraspeckle, whereas the middle portion is located in the interior. These data indicate that NEAT1 is folded and arranged within the paraspeckle, suggesting that the paraspeckle has a highly ordered structure that may contribute to the formation and functions of this nuclear body. A recent super-resolution microscopic study showed that paraspeckles are typically spherical and that specific proteins are localized to specific domains within a paraspeckle, implying a core–shell spheroidal structure (West et al. 2016).

Several studies have described the molecular functions of NEAT1. For example, NEAT1 regulates several specific types of RNAs, including IRAlu (inverted repeated Alu elements)-containing RNAs, of which 333 are present in human. mRNAs that contain IRAlu in their 3′ UTR are thought to be retained in paraspeckles (Chen and Carmichael 2009). In mouse, CTN mRNAs are retained in a manner dependent upon the paraspeckle component NONO/p54nrb and are exported in response to certain stimuli (Prasanth et al. 2005). Although the biological importance of this phenomenon is unknown, AG-rich RNAs are enriched in paraspeckles at their surface (West et al. 2016). In addition to regulating RNAs, the paraspeckle sequesters proteins and thus controls the free availability of these proteins in the nucleoplasm. Paraspeckle proteins such as SFPQ, which functions as a transcription activator or repressor dependent upon context, are sequestered in paraspeckles, thereby controlling expression of their target genes (Hirose et al. 2014b; Imamura et al. 2014). Together, paraspeckles function in gene regulation as molecular sponges for both RNAs and proteins. A study using the CHART (capture hybridization analysis of RNA targets) method showed that NEAT1 binds actively transcribed genes in specific chromosome loci, suggesting possible roles in direct regulation of these genes (West et al. 2014).

NEAT1 is induced by several stress-related, developmental, and pathological conditions. Proteasome inhibition by compounds such as MG132 and bortezomib induces NEAT1 expression, and NEAT1 knockout (KO) mouse embryonic fibroblasts are sensitive to MG132 treatment (Hirose et al. 2014b). NEAT1_2 is expressed in many cell lines, but not in ES cells. In mice, however, extensive investigation of NEAT1 expression by in situ hybridization revealed that NEAT1_2 is only expressed in a subset of cell types in tissues, whereas NEAT1_1 is expressed in the majority of cell types (Nakagawa et al. 2011, 2014). Consistent with this observation, paraspeckles are absent from most cells. Among the tissues that do have paraspeckles, NEAT1_2 is highly expressed in the corpus luteum. Consistent with this expression pattern, defects in pregnancy are observed in NEAT1 KO mice (Nakagawa et al. 2014). Also, paraspeckles are assembled in luminal epithelial cells in the mammary gland during development; accordingly, NEAT1 KO mice also exhibit defects in mammary gland development and lactation (Standaert et al. 2014).

In addition to the in vivo functions of NEAT1 under normal conditions, multiple studies have revealed its role in diseases. In particular, several reports have demonstrated the critical importance of NEAT1 in cancer. NEAT1 lncRNA is dysregulated (mainly upregulated) in many types of cancer. Moreover, NEAT1 is a prominent target gene of tumor suppressor p53 (Blume et al. 2015; Adriaens et al. 2016). NEAT1 expression is induced, and paraspeckles are assembled, by pharmacologically activating p53; alternatively, p53 can also be activated by oncogene-induced replication stress (Adriaens et al. 2016). In this context, NEAT1 prevents DNA damage resulting from replication stress (Adriaens et al. 2016). Paraspeckles form in tumor tissues, whereas normal tissues adjacent to cancer lack the paraspeckles. Strikingly, NEAT1 KO mice exhibit impaired skin tumorigenesis, indicating that NEAT1 promotes tumorigenesis (Adriaens et al. 2016). Furthermore, depletion of NEAT1 sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy by modulating DNA damage responses such as the ATR–CHK1 signaling pathway, suggesting a synthetic lethal interaction between NEAT1 and chemotherapeutic agents (Adriaens et al. 2016). Together, these observations strongly suggest that the NEAT1 lncRNA is a prominent target for increasing the genotoxicity of cancer chemotherapeutics.

In addition to being regulated by p53, paraspeckle formation is also induced in response to tumor hypoxia via transcriptional upregulation of NEAT1_2 by HIF2-alpha, thereby promoting cancer cell survival (Choudhry et al. 2014, 2015). Consistent with this, NEAT1 is the most upregulated lncRNA in prostate cancer. NEAT1 expression is regulated by estrogen receptor alpha and is associated with prostate cancer progression (Chakravarty et al. 2014). NEAT1 has been proposed to drive oncogenic growth by promoting epigenetic changes in the promoters of its target genes (Chakravarty et al. 2014). In addition, the short isoform NEAT1_1, but not NEAT1_2, promotes gene expression by inducing active chromatin states in prostate cancer, indicating that the two isoforms have distinct functions in this context. In addition, expression of NEAT1_2, but not NEAT1_1, predicts the response of ovarian cancer to platinum-based chemotherapy, providing further evidence that the isoforms play different roles (Adriaens et al. 2016). Very recently, NEAT1_1 was detected outside of the paraspeckles, where it forms numerous nucleoplasmic “microspeckles,” which were proposed to have paraspeckle-independent functions (Li et al. 2017). Accordingly, the precise dissection of NEAT1_1 and NEAT1_2 functions is essential for the development of applications of NEAT1. In addition to the dysregulation of its expression, NEAT1 is also highly mutated in several cancers, including liver cancer, although it remains unclear how these mutations affect NEAT1 functions (Fujimoto et al. 2016).

NEAT1 expression is also induced by viruses, including Japanese encephalitis virus, influenza virus, herpes simplex virus, measles, rabies virus, and hantavirus, as well as in HIV-infected cells (Saha et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2013; Imamura et al. 2014; Ma et al. 2017). In the case of influenza virus, NEAT1 is induced via the Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) pathway, resulting in elongation of paraspeckles (Imamura et al. 2014). The resultant elongated paraspeckles regulate immune-responsive genes, including interleukin-8 (IL-8), by sequestering paraspeckle proteins including SFPQ away from their target gene promoters, as in the case of paraspeckles induced by proteasome inhibition. Taken together, these observations highlight the broad importance of NEAT1 in antiviral responses.

NEAT1 is also implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases. For example, NEAT1 is upregulated in the early stage of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), but is not expressed in the same cells under normal conditions (Nishimoto et al. 2013). In addition, NEAT1 is significantly upregulated in the brains of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) patients (Tollervey et al. 2011; Tsuiji et al. 2013). NEAT1 is upregulated in Huntington’s disease, and NEAT1_1 expression prevents neuronal death in cell culture, suggesting that NEAT1 plays a protective role in Huntington’s (Sunwoo et al. 2017). By contrast, NEAT1 is acutely downregulated in response to neuronal activity (Barry et al. 2017). Many other paraspeckle proteins are linked to neurodegenerative diseases, including TDP-43, FUS, SS18L1, HNRNPA1, SFPQ, EWSR1, TAF15, and HNRNPH1 (Yamazaki and Hirose 2015; Taylor et al. 2016).

As described above, NEAT1 has pleiotropic functions in diseases and functions in a context-dependent manner. Precise dissection of the functions of NEAT1_1 and NEAT1_2 and their roles in physiological conditions is important for the development of applications. Notably in this regard, phosphorothioate-modified antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) can induce NEAT1-free paraspeckle-like foci in the nucleus (Shen et al. 2014). Similar approaches might enable intervention in the formation of various nuclear bodies, including paraspeckles, in vivo.

11.3.2 rIGS lncRNAs

Stresses induce dramatic changes in silent genomic regions. The nucleolar intergenic spacer (IGS), where heterochromatin normally forms and which is therefore transcriptionally silent, produces ribosomal IGS (rIGS) lncRNAs in response to several stresses, including acidosis, heat shock, hypoxia, serum starvation, aspirin treatment, and DNA damage (Audas et al. 2012a, b, 2016; Jacob et al. 2012, 2013). Knockdown of IGS lncRNAs disrupts the recruitment of target proteins, implying that IGS lncRNAs are arcRNAs (Audas et al. 2012a; Jacob et al. 2013). Under stress, rIGS lncRNAs form large subnucleolar structures called amyloid bodies (A-bodies, also called nucleolar detention centers [DCs]) (Audas et al. 2016). Unlike other nuclear bodies, A-bodies sequester and immobilize key cellular proteins in the nucleolus, as demonstrated by the immobilization of protein components revealed by FRAP (fluorescent recovery after photo-bleaching), proteinase K insensitivity, and staining with amyloid dyes such as 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonate, Congo red, and Amylo-Glo (Audas et al. 2012a, 2016, Jacob et al. 2013). Proteomic analysis revealed that A-bodies are characterized by physiological amyloids mediated by rIGS RNAs and the amyloid-converting motif (ACM), an arginine/histidine-rich sequence that is enriched in the A-body proteome (Audas et al. 2016). Proteomic analysis also showed that A-bodies have heterogeneous protein compositions and that their components include heat shock proteins such as HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90. The activity of heat shock proteins is required for disassembly of A-bodies, suggesting that the amyloid-like state of its protein components is reversible (Audas et al. 2016). Accordingly, it has been proposed that A-bodies serve to store large quantities of proteins in a dormant state.

There are several IGS lncRNAs, including rIGS28RNA, rIGS16RNA, rIGS22RNA, and rIGS20RNA, which are transcribed from regions ~28, 16, 22, and 20 kilobases (kb), respectively, downstream of the rRNA gene loci under specific stress conditions (Audas et al. 2012a). A-bodies constructed by these rIGS lncRNAs are functionally and compositionally distinct. For instance, the stress-responsive transcription factor HIF1A is degraded by the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) ubiquitin E3 ligase under normal conditions. However, under oxidative stress conditions, rIGS28RNA is induced and sequesters VHL, along with other cellular proteins, in the nucleolus. Knockdown of rIGS28RNA prevents localization of VHL to the nucleolus under oxidative stress (Audas et al. 2012a). In addition to VHL, many nuclear proteins, including DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and DNA polymerase delta 1 (POLD1), are also sequestered (Audas et al. 2012a). Under heat shock conditions, HSP70 is sequestered in the nucleolus in a rIGS16RNA- and rIGS22RNA-dependent manner (Audas et al. 2012a). Moreover, either heat shock or acidosis immobilizes RNA polymerase I subunits and rRNA processing proteins in A-bodies, thereby halting ribosome biogenesis. In addition, MDM2 is sequestered in the nucleolus by rIGS20RNA under transcriptional stress (Audas et al. 2012a; Jacob et al. 2013). These acidic and hypoxic conditions are thought to be prevalent in cancer microenvironments. Consistent with this, in human cancer tissues, IGS28RNA is induced, and several A-body components have been detected (Audas et al. 2016). In addition, rIGS28RNA-depleted MCF7 and PC3 cells form larger tumor masses in nude mouse xenograft assay (Audas et al. 2016).

The ability of rIGS lncRNAs to convert proteins into physiological amyloids by inducing a phase transition to a solid state is highly intriguing. Further dissection of specific RNA elements in rIGS lncRNAs may lead to the development of a method to induce such phase transitions in cellular contexts.

11.3.3 Satellite III lncRNA

Satellite III (Sat III) lncRNAs are primate-specific and essential components of the nuclear stress body (nSB) (Cotto et al. 1997; Chiodi et al. 2000; Denegri et al. 2002; Biamonti 2004; Jolly and Lakhotia 2006; Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). nSBs, which have a diameter of 0.3–3 micrometers, form in response to heat shock and several chemical stress conditions and are present in humans and monkeys, but not in rodents. Their formation is initiated by the transcription of Sat III lncRNAs, which are not expressed in non-stressed conditions, from pericentromeric heterochromatic regions (primarily 9q12 in human) (Chiodi et al. 2000; Denegri et al. 2002; Jolly and Lakhotia 2006; Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). As with nSBs, Sat III lncRNAs are strongly induced under various stress conditions, including heat shock (Valgardsdottir et al. 2008; Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). They are thought to be polyadenylated RNAs containing repetitive sequences with multiple tandem GGAAU or GGAGU repeats connected by linker sequences (Choo et al. 1990; Biamonti 2004; Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). The protein components of nSBs include several transcription factors, including HSF1, HSF2, TonEBP, TDP-43, and Sam68, as well as several splicing factors, including SAFB, SRSF1, SRSF7, and SRSF9 (Denegri et al. 2002; Biamonti 2004; Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). Formation of nSBs is initiated through a direct interaction between HSF1 and Sat III lncRNA (Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). Like paraspeckles, the nSB is a dynamic structure, as determined by FRAP measuring HSF1 dynamics (Audas et al. 2016). nSBs are thought to function in stress response and recovery by globally influencing gene expression via sequestration of transcription and splicing factors (Biamonti 2004; Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010). Our group reported that the SWI/SNF complex is required for the formation of nSBs, as well as the paraspeckles, suggesting its general importance in formation of nuclear bodies containing arcRNAs (Kawaguchi and Hirose 2015). When Sat III lncRNAs are knocked down, SRSF1 and SAFB cannot localize to nSBs, although HSF1 still localizes in nSBs, suggesting that Sat III can act as a scaffold for RBPs (Valgardsdottir et al. 2008). HSF1 is essential for the integrity of nSBs (Goenka et al. 2016). Consistent with this, RRM2 of SRSF1 is required for its targeting to nSBs, suggesting that splicing factors are recruited to Sat III lncRNA via direct RNA binding (Chiodi et al. 2004). Furthermore, artificial tethering experiments showed that Sat III lncRNA can initiate de novo formation of nSBs, indicating that it plays an architectural role (Shevtsov and Dundr 2011). In addition to stress conditions, SAT III is upregulated in A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells, as well as in several senescent cells, implying that it plays a role in cancer and senescence (Enukashvily et al. 2007).

11.3.4 HSATII RNA

In addition to the Sat III lncRNA, other satellite DNAs are transcribed into noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) under specific conditions. High-copy satellite II (HSATII) DNA is normally methylated and silenced, but DNA methylation of HSATII is frequently lost in cancer (Ting et al. 2011). Hence, HSATII RNA is aberrantly expressed in many tumors. Small blocks of HSATII are found in the pericentromeres of 11 human chromosomes, including chromosomes 2, 5, 7, 10, 13, 14, 15, 17, 21, 22, and Y (Hall et al. 2017). The transcribed HSATII RNA forms distinct large nuclear RNA foci, termed cancer-associated satellite transcript (CAST) bodies (Hall et al. 2017). These CAST bodies act as molecular sponges to sequester master epigenetic regulatory proteins, including MeCP2 (methyl-CpG-binding protein 2) and are thought to influence the epigenome in cancer cells. In that context, HSATII DNA and RNA form nuclear foci called cancer-associated Polycomb (CAP) bodies from the 1q12 mega-satellite, which also act as molecular sponges (Hall et al. 2017). CAP bodies sequester Polycomb group complex component PRC1. Sequestrations by CSAT and CAP bodies cause epigenetic instability, which is recognized as a hallmark of cancer (Hall et al. 2017). HSATII RNA is highly expressed in cancers, including pancreatic cancer, and is also expressed in preneoplastic pancreatic lesions, suggesting that it could serve as a biomarker for pancreatic cancer (Ting et al. 2011). HSATII RNA is also found in circulating blood of cancer patients; accordingly, a sensitive detection system has been developed to identify this biomarker (Kishikawa et al. 2016). In general, cancer-specific nuclear bodies constructed by HSATII RNA and DNA may serve as biomarkers of epigenetic instability, with diagnostic utility in several cancers.

11.3.5 Other arcRNAs

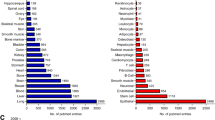

Our group has screened for nuclear structures that are diminished by RNase treatment. This approach has identified known and novel nuclear bodies, including the Sam68 nuclear body and a novel structure called the DBC1 body (Mannen et al. 2016). These findings suggest that these nuclear bodies, which are present in a subset of cancer cells, are constructed by unidentified arcRNAs. Interestingly, the Sam68 and DBC1 nuclear bodies are joined by the adaptor protein HNRNPL, warranting investigation of the underlying mechanism for this feature (Mannen et al. 2016). The number of validated arcRNAs is still limited, but we recently reported a method for identifying arcRNA candidates on a genome-wide scale (Chujo et al. 2017). This technique takes advantage of a characteristic feature of NEAT1, namely, that it is difficult to extract by conventional RNA extraction methods using acid–guanidine–phenol–chloroform (AGPC) reagents (e.g., Thermo Scientific, TRIzol). Shearing with a needle or heating improves the extraction efficiency of NEAT1. We termed this feature “semi-extractability” and RNAs with this property as “semi-extractable RNAs (seRNAs)” (Chujo et al. 2017). In addition to NEAT1, another arcRNA, rIGS16RNA, was semi-extractable, suggesting that this feature might help identify novel arcRNAs. A comparison of the expression levels of RNAs extracted by the conventional and improved methods revealed seRNAs throughout the genome, including 50 seRNAs in HeLa cells, as determined by RNA-seq (Chujo et al. 2017) (Fig. 11.2). Some of the seRNAs formed distinct nuclear foci that were distant from the transcription sites, indicating the formation of nuclear bodies (Chujo et al. 2017). The list of seRNAs contains several putative arcRNAs, including the LINE-1 and SPA, supporting the utility of this method for exploring arcRNAs at a genome-wide scale.

An experimental procedure to search semi-extractable RNAs. An example of workflows to search semi-extractable RNAs from cultured cells is shown. The cells are suspended in AGPC reagents such as TRIzol and divided into two groups for conventional and improved extraction methods. In the conventional method, the samples are directly subjected to RNA extraction. In the improved method, prior to RNA extraction, the samples are subjected to the needle shearing or heating. Both of the extracted RNAs are subjected to RNA-seq analyses. After the sequencing, the sequence reads in both samples are compared. Semi-extractable RNAs will be enriched in the RNAs extracted by the improved method

In addition to endogenous nuclear bodies, repeat RNAs form nuclear foci and play critical roles in pathogenesis in microsatellite expansion diseases such as myotonic dystrophy, a genetic disorder with multisystemic symptoms (Wojciechowska and Krzyzosiak 2011; Belzil et al. 2013; Nelson et al. 2013; Ramaswami et al. 2013; Mohan et al. 2014). Typically, such RNA granules sequester proteins. For example, expanded CTG or CCTG repeats are present in genomic DNA of patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1 or type 2, respectively (Wojciechowska and Krzyzosiak 2011). These repeats are transcribed into RNAs and form RNA foci that sequester RBP and MBNL; in mice, KOs of the corresponding genes cause myotonic dystrophy-like phenotypes (Kanadia et al. 2003). These data indicate that disease symptoms originate from toxic RNAs. Thus, understanding the mechanisms that dictate the biogenesis of these structures, which could be related to endogenous nuclear bodies, will help to develop therapeutic methods for these disorders.

11.3.6 Commonalities and Potential Applications of arcRNAs

In this section, I summarize the commonalities of arcRNAs and arcRNA-constructed nuclear bodies and discuss the reasons why RNA is used as a scaffold or platform for nuclear bodies. In addition, I address potential applications of arcRNAs.

First, most arcRNAs serve as the molecular sponges for proteins and, in some cases, RNAs (Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010; Hirose et al. 2014b; Imamura et al. 2014; Audas et al. 2016; Hall et al. 2017). It is possible that biochemical reactions and RNP assembly can also take place in these compartments, as observed for proteinaceous nuclear bodies. The components of nuclear bodies are usually dynamic (Fox et al. 2002). In the case of rIGS lncRNAs, the component proteins are completely detained within the bodies (Audas et al. 2012a, 2016). These data suggest that the arcRNAs induce phase transitions among material states (i.e., liquid, hydrogel, and solid) and sequester different factors into distinct states.

Second, many protein components of arcRNA-constructed nuclear bodies contain proteins harboring PLDs, LCDs, or intrinsically disordered domains, suggesting that aggregation-prone sequences play a role in assembly of these bodies (Yamazaki and Hirose 2015). In fact, PLD-containing paraspeckle proteins are essential for the integrity of paraspeckles (Hennig et al. 2015). Whereas most proteins localizing in arcRNA-constructed nuclear bodies are dispensable for the integrity of the bodies, a few of them play an essential role in maintaining nuclear bodies, suggesting that they represent essential core factors.

Third, transcription of arcRNAs is essential for nucleation, leading to assembly of nuclear bodies. Shutdown of transcription quickly eliminates these bodies, indicating that arcRNA-regulated nuclear bodies are dynamically controlled and that sequestration by arcRNAs is reversible (Fox et al. 2002). Consistent with this, the arcRNAs characterized so far are all nuclear ncRNAs induced under stress and disease conditions (Chujo et al. 2016). The rIGS, Sat III, and HSATII lncRNAs are transcriptionally silenced under normal conditions but are dramatically induced in response to stress or disease (Biamonti and Vourc’h 2010; Audas et al. 2012a, 2016; Hall et al. 2017). Several arcRNAs are aberrantly expressed in disease such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders (Yamazaki and Hirose 2015; Hall et al. 2017). Therefore, it is conceivable that the primary physiological roles of arcRNAs are related to stress and disease, raising the possibility that identification of arcRNA candidates as seRNAs under various conditions might reveal important regulatory lncRNAs (Chujo et al. 2017).

Fourth, lncRNAs have an advantage as the architectural core of nuclear bodies: they do not require a frame for protein translation. Consequently, their sequences are presumably only constrained by the requirement to form RNA–protein interaction, and arcRNAs have more flexibility to add and change their sequences than proteins, in which changes might cause aggregation. This advantage allows lncRNAs to increase the diversity of their binding partners and the combinations of proteins that are incorporated into nuclear bodies, likely via interactions with unique sequences or structures irrelevant to their protein–protein interaction potential (Chujo et al. 2016). This feature enables the formation of a wide range of nuclear bodies, allowing more rapid adaptation to demands for circumstantial change. Because there are more than 1000 RBPs in human cells, the RBPs that bind to arcRNAs can in turn sequester proteins that interact with RBPs (Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2012, 2016). The nature of this scaffolding should be suitable for integrating diverse regulatory proteins into specific sites.

Fifth, various repetitive sequences in NEAT1 lncRNA and other arcRNAs derived from satellite regions contain, or consist primarily of, repetitive sequences (Ulitsky and Bartel 2013; Chujo et al. 2016). Half of our genome comprises repeat sequences, including SINEs, LINEs, pseudogenes, endogenous viruses, and other repeats (Steitz 2015). Although these repetitive sequences are usually ignored in genomic and transcriptome analyses, arcRNAs derived from these repetitive sequences could be important regulators of the genome.

Overall, many recent studies have demonstrated that nuclear bodies are phase-separated into liquid, hydrogel, or solid states in cells (Courchaine et al. 2016; Banani et al. 2017). RNA is a suitable molecule for nucleating nuclear bodies by inducing phase separation. Specifically, arcRNAs are thought to induce phase separation by increasing the local concentration of proteins containing PLDs or LCDs and/or via direct RNA–RNA interaction (Chujo et al. 2016). The arcRNAs validated to date induce phase separation into different material states, as mentioned above. These states are likely to be defined by the sequences of arcRNAs, which serve as scaffolds for specific RBPs. By understanding the principles underlying the regulation of nuclear bodies by RNA elements in arcRNAs, it might be possible to artificially control phase separation among several material states that have different molecular dynamics in cells. This could lead in turn to the development of biochemical micro-reactors, cellular compartments that can achieve specific biochemical reactions by recruiting specific sets of protein and nucleic acids. This strategy could enable intervention in cellular functions such as gene and epigenome regulation. In addition, as noted above, phosphorothioate-modified ASOs can induce NEAT1-free paraspeckle-like foci in the nucleus, and ASOs have recently been approved for therapeutic uses in diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Accordingly, ASO or related methods hold promise for control of phase separation and nuclear body formation in vivo (Shen et al. 2014).

arcRNAs are an emerging class of lncRNAs for potential therapeutic targets and other applications. RNA-seq taking advantage of semi-extractability could launch a new era in arcRNA research and lead to the identification of new biomarkers, therapeutic targets for diseases, and methods for intervening in cellular functions (Chujo et al. 2017).

11.4 Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Decoding RNA elements and their protein partners is analogous to understanding the domains or motifs of proteins (Hirose et al. 2014a). In the case of proteins, this understanding has led to the development of inhibitors or activators of specific functions of multifunctional proteins. Similarly, the understanding of lncRNA elements would help develop methods to repress or activate specific functions of lncRNAs, although currently we are only capable of modulating all functions of a given lncRNA. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) has been used to target domains of XIST lncRNA that is essential for X chromosome inactivation and can repress domain-specific functions by blocking the interaction between XIST lncRNA and specific proteins (Sarma et al. 2010). Furthermore, RNA can dynamically change its secondary structure. Therefore, specific inhibition or activation of lncRNA domains could be achieved by modulating the corresponding RNA structures. It will be important to focus on the RNA elements and to accumulate knowledge about these elements.

We now have access to CRISPR interference (CRISPRi), a new method for exploring the functions of lncRNA on a genome-wide scale, as described above (Liu et al. 2017). This is a very powerful tool for exploring functionally important disease-linked lncRNAs. Because lncRNAs are expressed in specific tissues and cells, they are suitable targets for therapeutics with minimal side effects. In addition, many new approaches have been developed for investigating the biological importance of lncRNAs. One of them, CRISPR-mediated KO of lncRNAs in model organisms, is very useful for investigating the roles of these RNAs under physiological conditions. Although CRISPR is powerful, some lncRNAs are generated from multiple genomic loci, and therefore it might be difficult to repress their functions. In this case, an alternative strategy would be direct knockdown of lncRNAs. Because many lncRNAs are localized in the nucleus, siRNA-based methods are usually not capable of targeting them efficiently. However, knockdown using ASOs represents a powerful alternative approach for exploring the functions of nuclear-retained lncRNAs (Ideue et al. 2009). In addition, several methods have been designed to investigate the RNA elements in lncRNAs by elucidating the interactions between lncRNAs and proteins; these include RNA-centric technologies such as ChIRP (chromatin isolation by RNA purification), CHART, and RAP (RNA antisense purification) and protein-centric technologies such as CLIP (cross-linking immunoprecipitation) (Kashi et al. 2016). In addition, technologies for probing RNA secondary structure would also be useful (Lu and Chang 2016). Together, these new strategies will help to expand our understanding of RNA elements in lncRNAs.

References

Adriaens C, Standaert L, Barra J, Latil M, Verfaillie A, Kalev P, Boeckx B, Wijnhoven PW, Radaelli E, Vermi W, Leucci E, Lapouge G, Beck B, van den Oord J, Nakagawa S, Hirose T, Sablina AA, Lambrechts D, Aerts S, Blanpain C, Marine JC (2016) p53 induces formation of NEAT1 lncRNA-containing paraspeckles that modulate replication stress response and chemosensitivity. Nat Med 22:861–868

Aguzzi A, Altmeyer M (2016) Phase separation: linking cellular compartmentalization to disease. Trends Cell Biol 26:547–558

Alberti S, Hyman AA (2016) Are aberrant phase transitions a driver of cellular aging? BioEssays 38:959–968

Anderson DM, Anderson KM, Chang CL, Makarewich CA, Nelson BR, McAnally JR, Kasaragod P, Shelton JM, Liou J, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN (2015) A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell 160:595–606

Ashwal-Fluss R, Meyer M, Pamudurti NR, Ivanov A, Bartok O, Hanan M, Evantal N, Memczak S, Rajewsky N, Kadener S (2014) circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell 56:55–66

Audas TE, Jacob MD, Lee S (2012a) Immobilization of proteins in the nucleolus by ribosomal intergenic spacer noncoding RNA. Mol Cell 45:147–517

Audas TE, Jacob MD, Lee S (2012b) The nucleolar detention pathway: a cellular strategy for regulating molecular networks. Cell Cycle 11:2059–2062

Audas TE, Audas DE, Jacob MD, Ho JJ, Khacho M, Wang M, Perera JK, Gardiner C, Bennett CA, Head T, Kryvenko ON, Jorda M, Daunert S, Malhotra A, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Gonzalgo ML, Lee S (2016) Adaptation to stressors by systemic protein amyloidogenesis. Dev Cell 39:155–168

Baltz AG, Munschauer M, Schwanhäusser B, Vasile A, Murakawa Y, Schueler M, Youngs N, Penfold-Brown D, Drew K, Milek M, Wyler E, Bonneau R, Selbach M, Dieterich C, Landthaler M (2012) The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol Cell 46:674–690

Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK (2017) Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18:285–298

Barry G, Briggs JA, Hwang DW, Nayler SP, Fortuna PR, Jonkhout N, Dachet F, Maag JL, Mestdagh P, Singh EM, Avesson L, Kaczorowski DC, Ozturk E, Jones NC, Vetter I, Arriola-Martinez L, Hu J, Franco GR, Warn VM, Gong A, Dinger ME, Rigo F, Lipovich L, Morris MJ, O'Brien TJ, Lee DS, Loeb JA, Blackshaw S, Mattick JS, Wolvetang EJ (2017) The long non-coding RNA NEAT1 is responsive to neuronal activity and is associated with hyperexcitability states. Sci Rep 7:40127

Batista PJ, Chang HY (2013) Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell 152:1298–1307

Belzil VV, Gendron TF, Petrucelli L (2013) RNA-mediated toxicity in neurodegenerative disease. Mol Cell Neurosci 56:406–419

Bertone P, Stolc V, Royce TE, Rozowsky JS, Urban AE, Zhu X, Rinn JL, Tongprasit W, Samanta M, Weissman S, Gerstein M, Snyder M (2004) Global identification of human transcribed sequences with genome tiling arrays. Science 306:2242–2246

Biamonti G (2004) Nuclear stress bodies: a heterochromatin affair? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:493–498

Biamonti G, Vourc’h C (2010) Nuclear stress bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000695

Blume CJ, Hotz-Wagenblatt A, Hüllein J, Sellner L, Jethwa A, Stolz T, Slabicki M, Lee K, Sharathchandra A, Benner A, Dietrich S, Oakes CC, Dreger P, te Raa D, Kater AP, Jauch A, Merkel O, Oren M, Hielscher T, Zenz T (2015) p53-dependent non-coding RNA networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 29:2015–2023

Brown JA, Valenstein ML, Yario TA, Tycowski KT, Steitz JA (2012) Formation of triple-helical structures by the 3′-end sequences of MALAT1 and MENβ noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:19202–19207

Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, Kodzius R, Shimokawa K, Bajic VB, Brenner SE, Batalov S, Forrest AR, Zavolan M, Davis MJ, Wilming LG, Aidinis V, Allen JE, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Apweiler R, Aturaliya RN, Bailey TL, Bansal M, Baxter L, Beisel KW, Bersano T, Bono H, Chalk AM, Chiu KP, Choudhary V, Christoffels A, Clutterbuck DR, Crowe ML, Dalla E, Dalrymple BP, de Bono B, Della Gatta G, di Bernardo D, Down T, Engstrom P, Fagiolini M, Faulkner G, Fletcher CF, Fukushima T, Furuno M, Futaki S, Gariboldi M, Georgii-Hemming P, Gingeras TR, Gojobori T, Green RE, Gustincich S, Harbers M, Hayashi Y, Hensch TK, Hirokawa N, Hill D, Huminiecki L, Iacono M, Ikeo K, Iwama A, Ishikawa T, Jakt M, Kanapin A, Katoh M, Kawasawa Y, Kelso J, Kitamura H, Kitano H, Kollias G, Krishnan SP, Kruger A, Kummerfeld SK, Kurochkin IV, Lareau LF, Lazarevic D, Lipovich L, Liu J, Liuni S, McWilliam S, Madan Babu M, Madera M, Marchionni L, Matsuda H, Matsuzawa S, Miki H, Mignone F, Miyake S, Morris K, Mottagui-Tabar S, Mulder N, Nakano N, Nakauchi H, Ng P, Nilsson R, Nishiguchi S, Nishikawa S, Nori F, Ohara O, Okazaki Y, Orlando V, Pang KC, Pavan WJ, Pavesi G, Pesole G, Petrovsky N, Piazza S, Reed J, Reid JF, Ring BZ, Ringwald M, Rost B, Ruan Y, Salzberg SL, Sandelin A, Schneider C, Schönbach C, Sekiguchi K, Semple CA, Seno S, Sessa L, Sheng Y, Shibata Y, Shimada H, Shimada K, Silva D, Sinclair B, Sperling S, Stupka E, Sugiura K, Sultana R, Takenaka Y, Taki K, Tammoja K, Tan SL, Tang S, Taylor MS, Tegner J, Teichmann SA, Ueda HR, van Nimwegen E, Verardo R, Wei CL, Yagi K, Yamanishi H, Zabarovsky E, Zhu S, Zimmer A, Hide W, Bult C, Grimmond SM, Teasdale RD, Liu ET, Brusic V, Quackenbush J, Wahlestedt C, Mattick JS, Hume DA, Kai C, Sasaki D, Tomaru Y, Fukuda S, Kanamori-Katayama M, Suzuki M, Aoki J, Arakawa T, Iida J, Imamura K, Itoh M, Kato T, Kawaji H, Kawagashira N, Kawashima T, Kojima M, Kondo S, Konno H, Nakano K, Ninomiya N, Nishio T, Okada M, Plessy C, Shibata K, Shiraki T, Suzuki S, Tagami M, Waki K, Watahiki A, Okamura-Oho Y, Suzuki H, Kawai J, Hayashizaki Y, FANTOM Consortium, RIKEN Genome Exploration Research Group, GenomeScience Group (Genome Network Project Core Group) (2005) The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science 309:1559–1563

Carrieri C, Cimatti L, Biagioli M, Beugnet A, Zucchelli S, Fedele S, Pesce E, Ferrer I, Collavin L, Santoro C, Forrest AR, Carninci P, Biffo S, Stupka E, Gustincich S (2012) Long non-coding antisense RNA controls Uchl1 translation through an embedded SINEB2 repeat. Nature 491:454–457

Castello A, Fischer B, Eichelbaum K, Horos R, Beckmann BM, Strein C, Davey NE, Humphreys DT, Preiss T, Steinmetz LM, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW (2012) Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149:1393–1406

Castello A, Fischer B, Frese CK, Horos R, Alleaume AM, Foehr S, Curk T, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW (2016) Comprehensive identification of RNA-binding domains in human cells. Mol Cell 63:696–710

Cech TR, Steitz JA (2014) The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell 157:77–94

Chakravarty D, Sboner A, Nair SS, Giannopoulou E, Li R, Hennig S, Mosquera JM, Pauwels J, Park K, Kossai M, MacDonald TY, Fontugne J, Erho N, Vergara IA, Ghadessi M, Davicioni E, Jenkins RB, Palanisamy N, Chen Z, Nakagawa S, Hirose T, Bander NH, Beltran H, Fox AH, Elemento O, Rubin MA (2014) The oestrogen receptor alpha-regulated lncRNA NEAT1 is a critical modulator of prostate cancer. Nat Commun 5:5383

Chen LL (2016a) The biogenesis and emerging roles of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17:205–211

Chen LL (2016b) Linking long noncoding RNA localization and function. Trends Biochem Sci 41:761–772

Chen LL, Carmichael GG (2009) Altered nuclear retention of mRNAs containing inverted repeats in human embryonic stem cells: functional role of a nuclear noncoding RNA. Mol Cell 35:467–478

Chen CK, Blanco M, Jackson C, Aznauryan E, Ollikainen N, Surka C, Chow A, Cerase A, McDonel P, Guttman M (2016) Xist recruits the X chromosome to the nuclear lamina to enable chromosome-wide silencing. Science 354:468–472

Chiodi I, Biggiogera M, Denegri M, Corioni M, Weighardt F, Cobianchi F, Riva S, Biamonti G (2000) Structure and dynamics of hnRNP-labelled nuclear bodies induced by stress treatments. J Cell Sci 113(Pt 22):4043–4053

Chiodi I, Corioni M, Giordano M, Valgardsdottir R, Ghigna C, Cobianchi F, Xu RM, Riva S, Biamonti G (2004) RNA recognition motif 2 directs the recruitment of SF2/ASF to nuclear stress bodies. Nucleic Acids Res 32:4127–4136

Choo KH, Earle E, Mcquikkan C (1990) A homologous subfamily of satellite III DNA on human chromosomes 14 and 22. Nucleic Acids Res 18:5641–5648

Choudhry H, Schödel J, Oikonomopoulos S, Camps C, Grampp S, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ, Ragoussis J, Mole DR (2014) Extensive regulation of the non-coding transcriptome by hypoxia: role of HIF in releasing paused RNApol2. EMBO Rep 15:70–76

Choudhry H, Albukhari A, Morotti M, Haider S, Moralli D, Smythies J, Schödel J, Green CM, Camps C, Buffa F, Ratcliffe P, Ragoussis J, Harris AL, Mole DR (2015) Tumor hypoxia induces nuclear paraspeckle formation through HIF-2alpha dependent transcriptional activation of NEAT1 leading to cancer cell survival. Oncogene 34:4546

Chu C, Zhang QC, da Rocha ST, Flynn RA, Bharadwaj M, Calabrese JM, Magnuson T, Heard E, Chang HY (2015) Systematic discovery of Xist RNA binding proteins. Cell 161:404–416

Chujo T, Yamazaki T, Hirose T (2016) Architectural RNAs (arcRNAs): a class of long noncoding RNAs that function as the scaffold of nuclear bodies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1859:139–146

Chujo T, Yamazaki T, Kawaguchi T, Kurosaka S, Takumi T, Nakagawa S, Hirose T (2017) Unusual semi-extractability as a hallmark of nuclear body-associated architectural noncoding RNAs. EMBO J 36:1447–1462

Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, Lawrence JB (2009) An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell 33:717–726

Conrad NK, Steitz JA (2005) A Kaposi's sarcoma virus RNA element that increases the nuclear abundance of intronless transcripts. EMBO J 24:1831–1841

Cotto J, Fox S, Morimoto R (1997) HSF1 granules: a novel stress-induced nuclear compartment of human cells. J Cell Sci 110(Pt 23):2925–2934

Courchaine EM, Lu A, Neugebauer KM (2016) Droplet organelles? EMBO J 35:1603–1612

Denegri M, Moralli D, Rocchi M, Biggiogera M, Raimondi E, Cobianchi F, De Carli L, Riva S, Biamonti G (2002) Human chromosomes 9, 12, and 15 contain the nucleation sites of stress-induced nuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell 13:2069–2079

Engreitz JM, Haines JE, Perez EM, Munson G, Chen J, Kane M, McDonel PE, Guttman M, Lander ES (2016a) Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature 539:452–455

Engreitz JM, Ollikainen N, Guttman M (2016b) Long non-coding RNAs: spatial amplifiers that control nuclear structure and gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17:756–770

Engström PG, Suzuki H, Ninomiya N, Akalin A, Sessa L, Lavorgna G, Brozzi A, Luzi L, Tan SL, Yang L, Kunarso G, Ng EL, Batalov S, Wahlestedt C, Kai C, Kawai J, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Wells C, Bajic VB, Orlando V, Reid JF, Lenhard B, Lipovich L (2006) Complex Loci in human and mouse genomes. PLoS Genet 2:e47

Enukashvily NI, Donev R, Waisertreiger IS, Podgornaya OI (2007) Human chromosome 1 satellite 3 DNA is decondensed, demethylated and transcribed in senescent cells and in A431 epithelial carcinoma cells. Cytogenet Genome Res 118:42–54

Fong KW, Li Y, Wang W, Ma W, Li K, Qi RZ, Liu D, Songyang Z, Chen J (2013) Whole-genome screening identifies proteins localized to distinct nuclear bodies. J Cell Biol 203:149–164

Fox AH, Lam YW, Leung AK, Lyon CE, Andersen J, Mann M, Lamond AI (2002) Paraspeckles: a novel nuclear domain. Curr Biol 12:13–25

Fujimoto A, Furuta M, Totoki Y, Tsunoda T, Kato M, Shiraishi Y, Tanaka H, Taniguchi H, Kawakami Y, Ueno M, Gotoh K, Ariizumi S, Wardell CP, Hayami S, Nakamura T, Aikata H, Arihiro K, Boroevich KA, Abe T, Nakano K, Maejima K, Sasaki-Oku A, Ohsawa A, Shibuya T, Nakamura H, Hama N, Hosoda F, Arai Y, Ohashi S, Urushidate T, Nagae G, Yamamoto S, Ueda H, Tatsuno K, Ojima H, Hiraoka N, Okusaka T, Kubo M, Marubashi S, Yamada T, Hirano S, Yamamoto M, Ohdan H, Shimada K, Ishikawa O, Yamaue H, Chayama K, Miyano S, Aburatani H, Shibata T, Nakagawa H (2016) Whole-genome mutational landscape and characterization of noncoding and structural mutations in liver cancer. Nat Genet 48:500–509

Geisler S, Coller J (2013) RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14:699–712

Goenka A, Sengupta S, Pandey R, Parihar R, Mohanta GC, Mukerji M, Ganesh S (2016) Human satellite-III non-coding RNAs modulate heat-shock-induced transcriptional repression. J Cell Sci 129:3541–3552

Gong C, Maquato LE (2011) lncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3′ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature 470:284–288

Guarnerio J, Bezzi M, Jeong JC, Paffenholz SV, Berry K, Naldini MM, Lo-Coco F, Tay Y, Beck AH, Pandolfi PP (2016) Oncogenic role of fusion-circRNAs derived from cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Cell 165:289–302

Guttman M, Rinn JL (2012) Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature 482:339–346

Hall LL, Byron M, Carone DM, Whitfield TW, Pouliot GP, Fischer A, Jones P, Lawrence JB (2017) Demethylated HSATII DNA and HSATII RNA foci sequester PRC1 and MeCP2 into cancer-specific nuclear bodies. Cell Rep 18:2943–2956

Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK, Kjems J (2013) Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 495:384–388

Hennig S, Kong G, Mannen T, Sadowska A, Kobelke S, Blythe A, Knott GJ, Iyer KS, Ho D, Newcombe EA, Hosoki K, Goshima N, Kawaguchi T, Hatters D, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Hirose T, Bond CS, Fox AH (2015) Prion-like domains in RNA binding proteins are essential for building subnuclear paraspeckles. J Cell Biol 210:529–539

Hirose T, Mishima Y, Tomari Y (2014a) Elements and machinery of non-coding RNAs: toward their taxonomy. EMBO Rep 15:489–507

Hirose T, Virnicchi G, Tanigawa A, Naganuma T, Li R, Kimura H, Yokoi T, Nakagawa S, Bénard M, Fox AH, Pierron G (2014b) NEAT1 long noncoding RNA regulates transcription via protein sequestration within subnuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell 25:169–183

Ideue T, Hino K, Kitao S, Yokoi T, Hirose T (2009) Efficient oligonucleotide-mediated degradation of nuclear noncoding RNAs in mammalian cultured cells. RNA 15:1578–1587

Imamura K, Imamachi N, Akizuki G, Kumakura M, Kawaguchi A, Nagata K, Kato A, Kawaguchi Y, Sato H, Yoneda M, Kai C, Yada T, Suzuki Y, Yamada T, Ozawa T, Kaneki K, Inoue T, Kobayashi M, Kodama T, Wada Y, Sekimizu K, Akimitsu N (2014) Long noncoding RNA NEAT1-dependent SFPQ relocation from promoter region to paraspeckle mediates IL8 expression upon immune stimuli. Mol Cell 53:393–406

Indrieri A, Grimaldi C, Zucchelli S, Tammaro R, Gustincich S, Franco B (2016) Synthetic long non-coding RNAs [SINEUPs] rescue defective gene expression in vivo. Sci Rep 6:27315

Jacob MD, Audas TE, Mullineux ST, Lee S (2012) Where no RNA polymerase has gone before: novel functional transcripts derived from the ribosomal intergenic spacer. Nucleus 3:315–319

Jacob MD, Audas TE, Uniacke J, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Lee S (2013) Environmental cues induce a long noncoding RNA-dependent remodeling of the nucleolus. Mol Biol Cell 24:2943–2953

Jolly C, Lakhotia SC (2006) Human sat III and Drosophila hsr omega transcripts: a common paradigm for regulation of nuclear RNA processing in stressed cells. Nucleic Acids Res 34:5508–5514

Kaikkonen MU, Spann NJ, Heinz S, Romanoski CE, Allison KA, Stender JD, Chun HB, Tough DF, Prinjha RK, Benner C, Glass CK (2013) Remodeling of the enhancer landscape during macrophage activation is coupled to enhancer transcription. Mol Cell 51:310–325

Kanadia RN, Johnstone KA, Mankodi A, Lungu C, Thornton CA, Esson D, Timmers AM, Hauswirth WW, Swanson MS (2003) A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science 302:1978–1980

Kapranov P, Cheng J, Dike S, Nix DA, Duttagupta R, Willingham AT, Stadler PF, Hertel J, Hackermüller J, Hofacker IL, Bell I, Cheung E, Drenkow J, Dumais E, Patel S, Helt G, Ganesh M, Ghosh S, Piccolboni A, Sementchenko V, Tammana H, Gingeras TR (2007) RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science 316:1484–1488

Kashi K, Henderson L, Bonetti A, Carninci P (2016) Discovery and functional analysis of lncRNAs: methodologies to investigate an uncharacterized transcriptome. Biochim Biophys Acta 1859:3–15

Katayama S, Tomaru Y, Kasukawa T, Waki K, Nakanishi M, Nakamura M, Nishida H, Yap CC, Suzuki M, Kawai J, Suzuki H, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Wells C, Frith M, Ravasi T, Pang KC, Hallinan J, Mattick J, Hume DA, Lipovich L, Batalov S, Engström PG, Mizuno Y, Faghihi MA, Sandelin A, Chalk AM, Mottagui-Tabar S, Liang Z, Lenhard B, Wahlestedt C, RIKEN Genome Exploration Research Group, Genome Science Group (Genome Network Project Core Group), FANTOM Consortium (2005) Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science 309:1564–1566

Kawaguchi T, Hirose T (2015) Chromatin remodeling complexes in the assembly of long noncoding RNA-dependent nuclear bodies. Nucleus 6:462–467

Kawaguchi T, Tanigawa A, Naganuma T, Ohkawa Y, Souquere S, Pierron G, Hirose T (2015) SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes function in noncoding RNA-dependent assembly of nuclear bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:4304–4309

Kishikawa T, Otsuka M, Yoshikawa T, Ohno M, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto N, Kotani A, Koike K (2016) Quantitation of circulating satellite RNAs in pancreatic cancer patients. JCI Insight 1:e86646

Kretz M, Siprashvili Z, Chu C, Webster DE, Zehnder A, Qu K, Lee CS, Flockhart RJ, Groff AF, Chow J, Johnston D, Kim GE, Spitale RC, Flynn RA, Zheng GX, Aiyer S, Raj A, Rinn JL, Chang HY, Khavari PA (2013) Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature 493:231–235

Lee M, Sadowska A, Bekere I, Ho D, Gully BS, Lu Y, Iyer KS, Trewhella J, Fox AH, Bond CS (2015) The structure of human SFPQ reveals a coiled-coil mediated polymer essential for functional aggregation in gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 43:3826–3840

Lee S, Kopp F, Chang TC, Sataluri A, Chen B, Sivakumar S, Yu H, Xie Y, Mendell JT (2016) Noncoding RNA NORAD regulates genomic stability by sequestering PUMILIO proteins. Cell 164:69–80

Legnini I, Di Timoteo G, Rossi F, Morlando M, Briganti F, Sthandier O, Fatica A, Santini T, Andronache A, Wade M, Laneve P, Rajewsky N, Bozzoni I (2017) Circ-ZNF609 is a circular RNA that can be translated and functions in myogenesis. Mol Cell 66:22–37

Li R, Harvey AR, Hodgetts SI, Fox AH (2017) Functional dissection of NEAT1 using genome editing reveals substantial localization of the NEAT1_1 isoform outside paraspeckles. RNA 23:872–881

Liang D, Wilusz JE (2014) Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes Dev 28:2233–2247

Liu SJ, Horlbeck MA, Cho SW, Birk HS, Malatesta M, He D, Attenello FJ, Villalta JE, Cho MY, Chen Y, Mandegar MA, Olvera MP, Gilbert LA, Conklin BR, Chang HY, Weissman JS, Lim DA (2017) CRISPRi-based genome-scale identification of functional long noncoding RNA loci in human cells. Science 355:aah7111

Lu Z, Chang HY (2016) Decoding the RNA structurome. Curr Opin Struct Biol 36:142–148

Ma H, Han P, Ye W, Chen H, Zheng X, Cheng L, Zhang L, Yu L, Wu X, Xu Z, Lei Y, Zhang F (2017) The long noncoding RNA NEAT1 exerts antihantaviral effects by acting as positive feedback for RIG-I signaling. J Virol 91:e02250–e02216

Mannen T, Yamashita S, Tomita K, Goshima N, Hirose T (2016) The Sam68 nuclear body is composed of two RNase-sensitive substructures joined by the adaptor HNRNPL. J Cell Biol 214:45–59

Mao YS, Sunwoo H, Zhang B, Spector DL (2011) Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol 13:95–101

Matsumoto A, Pasut A, Matsumoto M, Yamashita R, Fung J, Monteleone E, Saghatelian A, Nakayama KI, Clohessy JG, Pandolfi PP (2017) mTORC1 and muscle regeneration are regulated by the LINC00961-encoded SPAR polypeptide. Nature 541:228–232

McHugh CA, Chen CK, Chow A, Surka CF, Tran C, McDonel P, Pandya-Jones A, Blanco M, Burghard C, Moradian A, Sweredoski MJ, Shishkin AA, Su J, Lander ES, Hess S, Plath K, Guttman M (2015) The Xist lncRNA interacts directly with SHARP to silence transcription through HDAC3. Nature 521:232–236

Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, Loewer A, Ziebold U, Landthaler M, Kocks C, le Noble F, Rajewsky N (2013) Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495:333–338

Mohan A, Goodwin M, Swanson MS (2014) RNA-protein interactions in unstable microsatellite diseases. Brain Res 1584:3–14

Naganuma T, Nakagawa S, Tanigawa A, Sasaki YF, Goshima N, Hirose T (2012) Alternative 3′-end processing of long noncoding RNA initiates construction of nuclear paraspeckles. EMBO J 31:4020–4034

Nakagawa S, Naganuma T, Shioi G, Hirose T (2011) Paraspeckles are subpopulation-specific nuclear bodies that are not essential in mice. J Cell Biol 193:31–39

Nakagawa S, Shimada M, Yanaka K, Mito M, Arai T, Takahashi E, Fujita Y, Fujimori T, Standaert L, Marine JC, Hirose T (2014) The lncRNA Neat1 is required for corpus luteum formation and the establishment of pregnancy in a subpopulation of mice. Development 141:4618–4627

Nelson DL, Orr HT, Warren ST (2013) The unstable repeats--three evolving faces of neurological disease. Neuron 77:825–843

Nelson BR, Makarewich CA, Anderson DM, Winders BR, Troupes CD, Wu F, Reese AL, McAnally JR, Chen X, Kavalali ET, Cannon SC, Houser SR, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN (2016) A peptide encoded by a transcript annotated as long noncoding RNA enhances SERCA activity in muscle. Science 351:271–275

Nishimoto Y, Nakagawa S, Hirose T, Okano HJ, Takao M, Shibata S, Suyama S, Kuwako K, Imai T, Murayama S, Suzuki N, Okano H (2013) The long non-coding RNA nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1_2 induces paraspeckle formation in the motor neuron during the early phase of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Brain 6:31

Paralkar VR, Taborda CC, Huang P, Yao Y, Kossenkov AV, Prasad R, Luan J, Davies JO, Hughes JR, Hardison RC, Blobel GA, Weiss MJ (2016) Unlinking an lncRNA from its associated cis element. Mol Cell 62:104–110

Passon DM, Lee M, Rackham O, Stanley WA, Sadowska A, Filipovska A, Fox AH, Bond CS (2012) Structure of the heterodimer of human NONO and paraspeckle protein component 1 and analysis of its role in subnuclear body formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:4846–4850

Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W (2009) Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 136:629–641

Prasanth KV, Prasanth SG, Xuan Z, Hearn S, Freier SM, Bennett CF, Zhang MQ, Spector DL (2005) Regulating gene expression through RNA nuclear retention. Cell 123:249–263

Quinn JJ, Chang HY (2016) Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet 17:47–62

Ramaswami M, Taylor JP, Parker R (2013) Altered ribostasis: RNA-protein granules in degenerative disorders. Cell 154:727–736

Rinn JL, Chang HY (2012) Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 81:145–166

Saha S, Sugumar P, Bhandari P, Rangarajan PN (2006) Identification of Japanese encephalitis virus-inducible genes in mouse brain and characterization of GARG39/IFIT2 as a microtubule-associated protein. J Gen Virol 87:3285–3289

Salzman J (2016) Circular RNA expression: its potential regulation and function. Trends Genet 32:309–316

Sarma K, Levasseur P, Aristarkhov A, Lee JT (2010) Locked nucleic acids (LNAs) reveal sequence requirements and kinetics of Xist RNA localization to the X chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:22196–22201

Sasaki YT, Ideue T, Sano M, Mituyama T, Hirose T (2009) MENepsilon/beta noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:2525–2530

Schmitt AM, Chang HY (2016) Long noncoding RNAs in cancer pathways. Cancer Cell 29:452–463

Shen W, Liang XH, Crooke ST (2014) Phosphorothioate oligonucleotides can displace NEAT1 RNA and form nuclear paraspeckle-like structures. Nucleic Acids Res 42:8648–8662

Shevtsov SP, Dundr M (2011) Nucleation of nuclear bodies by RNA. Nat Cell Biol 13:167–173

Souquere S, Beauclair G, Harper F, Fox A, Pierron G (2010) Highly ordered spatial organization of the structural long noncoding NEAT1 RNAs within paraspeckle nuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell 21:4020–4027

Standaert L, Adriaens C, Radaelli E, Van Keymeulen A, Blanpain C, Hirose T, Nakagawa S, Marine JC (2014) The long noncoding RNA Neat1 is required for mammary gland development and lactation. RNA 20:1844–1849

Steitz J (2015) RNA-RNA base-pairing: theme and variations. RNA 21:476–477

Sunwoo H, Dinger ME, Wilusz JE, Amaral PP, Mattick JS, Spector DL (2009) MEN epsilon/beta nuclear-retained non-coding RNAs are up-regulated upon muscle differentiation and are essential components of paraspeckles. Genome Res 19:347–359

Sunwoo JS, Lee ST, Im W, Lee M, Byun JI, Jung KH, Park KI, Jung KY, Lee SK, Chu K, Kim M (2017) Altered expression of the long noncoding RNA NEAT1 in Huntington’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 54:1577–1586

Takahashi H, Carninci P (2014) Widespread genome transcription: new possibilities for RNA therapies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 452:294–301

Taniue K, Kurimoto A, Sugimasa H, Nasu E, Takeda Y, Iwasaki K, Nagashima T, Okada-Hatakeyama M, Oyama M, Kozuka-Hata H, Hiyoshi M, Kitayama J, Negishi L, Kawasaki Y, Akiyama T (2016) Long noncoding RNA UPAT promotes colon tumorigenesis by inhibiting degradation of UHRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:1273–1278

Taylor JP, Brown RH Jr, Cleveland DW (2016) Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 539:197–206

Ting DT, Lipson D, Paul S, Brannigan BW, Akhavanfard S, Coffman EJ, Contino G, Deshpande V, Iafrate AJ, Letovsky S, Rivera MN, Bardeesy N, Maheswaran S, Haber DA (2011) Aberrant overexpression of satellite repeats in pancreatic and other epithelial cancers. Science 331:593–596

Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, Briese M, Cereda M, Kayikci M, König J, Hortobágyi T, Nishimura AL, Zupunski V, Patani R, Chandran S, Rot G, Zupan B, Shaw CE, Ule J (2011) Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 14:452–458

Tsuiji H, Iguchi Y, Furuya A, Kataoka A, Hatsuta H, Atsuta N, Tanaka F, Hashizume Y, Akatsu H, Murayama S, Sobue G, Yamanaka K (2013) Spliceosome integrity is defective in the motor neuron diseases ALS and SMA. EMBO Mol Med 5:221–234

Tycowski KT, Shu MD, Borah S, Shi M, Steitz JA (2012) Conservation of a triple-helix-forming RNA stability element in noncoding and genomic RNAs of diverse viruses. Cell Rep 2:26–32

Tycowski KT, Shu MD, Steitz JA (2016) Myriad triple-helix-forming structures in the transposable element RNAs of plants and fungi. Cell Rep 15:1266–1276

Ulitsky I, Bartel DP (2013) lincRNAs: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell 154:26–46

Uversky VN (2016) Intrinsically disordered proteins in overcrowded milieu: membrane-less organelles, phase separation, and intrinsic disorder. Curr Opin Struct Biol 44:18–30

Valgardsdottir R, Chiodi I, Giordano M, Rossi A, Bazzini S, Ghigna C, Riva S, Biamonti G (2008) Transcription of Satellite III non-coding RNAs is a general stress response in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 36:423–434

Wahlestedt C (2013) Targeting long non-coding RNA to therapeutically upregulate gene expression. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:433–446

West JA, Davis CP, Sunwoo H, Simon MD, Sadreyev RI, Wang PI, Tolstorukov MY, Kingston RE (2014) The long noncoding RNAs NEAT1 and MALAT1 bind active chromatin sites. Mol Cell 55:791–802

West JA, Mito M, Kurosaka S, Takumi T, Tanegashima C, Chujo T, Yanaka K, Kingston RE, Hirose T, Bond C, Fox A, Nakagawa S (2016) Structural, super-resolution microscopy analysis of paraspeckle nuclear body organization. J Cell Biol 214:817–830

Wilusz JE, Freier SM, Spector D (2008) 3′ end processing of a long nuclear-retained noncoding RNA yields a tRNA-like cytoplasmic RNA. Cell 135:919–932

Wilusz JE, JnBaptiste CK, Lu LY, Kuhn CD, Joshua-Tor L, Sharp PA (2012) A triple helix stabilizes the 3′ ends of long noncoding RNAs that lack poly(A) tails. Genes Dev 26:2392–2407

Wojciechowska M, Krzyzosiak WJ (2011) Cellular toxicity of expanded RNA repeats: focus on RNA foci. Hum Mol Genet 20:3811–3821

Wu H (2013) Higher-order assemblies in a new paradigm of signal transduction. Cell 153:287–292

Yamazaki T, Hirose T (2015) The building process of the functional paraspeckle with long non-coding RNAs. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 7:1–41

Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Kim J, Yang X, Martindale JL, Tominaga-Yamanaka K, White EJ, Orjalo AV, Rinn JL, Kreft SG, Wilson GM, Gorospe M (2013) Scaffold function of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in protein ubiquitination. Nat Commun 4:2939

Zhang Q, Chen CY, Yedavalli VS, Jeang KT (2013) NEAT1 long noncoding RNA and paraspeckle bodies modulate HIV-1 posttranscriptional expression. MBio 4:e00596–e00512

Zucchelli S, Cotella D, Takahashi H, Carrieri C, Cimatti L, Fasolo F, Jones MH, Sblattero D, Sanges R, Santoro C, Persichetti F, Carninci P, Gustincich S (2015a) SINEUPs: a new class of natural and synthetic antisense long non-coding RNAs that activate translation. RNA Biol 12:771–779

Zucchelli S, Fasolo F, Russo R, Cimatti L, Patrucco L, Takahashi H, Jones MH, Santoro C, Sblattero D, Cotella D, Persichetti F, Carninci P, Gustincich S (2015b) SINEUPs are modular antisense long non-coding RNAs that increase synthesis of target proteins in cells. Front Cell Neurosci 9:174