Abstract

Schools have long been integrally involved in initial teacher education particularly through the professional experience component. In recent decades however, there have been specific policy calls for greater involvement of schools in teacher preparation. These calls have come in two distinct waves of partnership policy reforms in Australia. The first began in earnest with the Australian Government announcement through the National Partnership Agreement on Improving Teacher Quality (Council of Australian Governments (COAG) National partnership agreement on improving teacher quality, 2008), which identified two priorities. Firstly, it championed a systemic response to strengthening linkages between schools and universities, and secondly, it recognised the professional learning opportunities of preservice teachers and in-service teachers working together as co-producers of knowledge. The second wave, influenced by the Melbourne Declaration (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs MCEETYA. Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians, 2008), resulted in the government response to the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) report (Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). Action now: classroom ready teachers. Australian Government, Canberra, 2015) and the accompanying move to mandate school-university partnerships for the purpose of teacher education program accreditation. These national partnership priorities have been taken up in different ways across the various states and territories and by universities and schools. This chapter maps the policy reforms both nationally and at the various jurisdictional levels and uses four illustrative cases to analyse the opportunities and challenges for future partnerships and recommendations for teacher educators working to sustain such partnerships.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Professional experience

- Partnerships

- Practicum

- Work-integrated learning

- Initial teacher education

- School-university partnerships

Introduction

Schools have always been integrally involved in initial teacher education in Australia. At different times throughout the history of teacher preparation, schools have either been the central site of learning to teach or positioned in partnership with universities via the provision of professional experience. Aspland (2006) neatly maps the historical trends in teacher preparation in Australia beginning with the establishment of ‘normal schools’ at the end of the nineteenth century responsible for the training of ‘pupil students’ as teachers in the tradition of an apprenticeship model: through to the move of teacher preparation from teaching colleges to universities in the late period of the twentieth century, which heralded the professionalisation of teaching. No matter the level of school involvement on this continuum throughout each historical period, there has also been accompanying critique and debates about the best ways of learning about theory and practice (White & Forgasz, 2016). The turn of the century, however, has seen these debates intensify with an ever-increasing level of scrutiny with initial teacher education now a national policy focus like never before (Fitzgerald & Knipe, 2016).

Accompanying the debates have been numerous reviews into teacher education as outlined by Louden (2008) in his paper 101 Damnations: The Persistence of Criticism and the Absence of Evidence About Teacher Education in Australia. More recently Bahr and Mellor’s (2016) review paper Building Quality in Teaching and Teacher Education explores the idea of quality teaching within Australia, with a focus on the role of teacher education and teacher educators in ensuring the graduation of quality teachers. They also problematise the current focus on quality teaching as a more public and political view of teaching rather than a view informed by and for the profession. Underpinning current critiques about teacher education are long-held historical tensions between the perceived divide between ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ and the best approaches and places to prepare teachers (see White & Forgasz, 2016).

The latest global policy response is a trend in teacher education back to earlier historical school-based models. Such approaches appear to be characterised by a return to an apprenticeship and training model, with a greater focus on the central involvement of schools in initial teacher education, and call for more time in schools for preservice teachers. Current policy reforms require more formal links to be made between schools and universities through a ‘partnership’ agenda. The changes to current policy in the national accreditation requirements for initial teacher education providers (AITSL, 2015, 2016) herald the formalisation of links between schools and universities through newly mandated partnership agreements.

This chapter examines the current Australian partnership policy agenda noting the changing historical document policy landscape and discussing the implications for universities and schools enacted across four state-based jurisdictions. The four cases are drawn across different states, namely, New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia. The authors, each based in one of the four jurisdictions, conducted a qualitative study using document analysis to interrogate the national and state-based teacher education policy documents to better understand the current trends and epistemological views underpinning them. These school-university partnership cases, drawn from various locations in Australia, were then purposefully connected to better understand the policy implications for diverse settings.

While the four cases are independent of each other and remain as policy case studies in their own right, the authors have deliberately connected them through a series of research questions as part of an overarching study as outlined further in the chapter. By purposefully overlaying the studies, the authors have also responded to the challenge for teacher educators ‘to align strategically smaller-scale studies that when analysed and viewed together will highlight common themes, as well as shine a light on diversity and context relevant matters’ (White, 2016, p. vii). The chapter concludes with contextual insights into the partnership policy-practice nexus and highlights recommendations for future partnership endeavours and agreements.

Connecting Partnership Policy: An Exploration Across Our Jurisdictions

Policy convergence and divergence (Ball, 2005) related to partnerships in different contexts in teacher education are the focus of this chapter. We examine the ways in which the national initial teacher education policy documents are influenced by global policies and in turn enacted at the state and more local levels. As authors, we take up what Ball (2015) notes as the distinction between ‘policy as text’ and ‘policy as discourse’. He notes:

[P]olicies are both ‘contested’, mediated and differentially represented by different actors in different contexts (policy as text), but on the other hand, at the same time produced and formed by taken-for-granted and implicit knowledges and assumptions about the world and ourselves (policy as discourse). (p. 311)

We explore partnership policy texts and discourses across four Australian states. The examination is framed by a policy trajectory approach to policy analysis (Ball, 1994). A policy trajectory approach seeks to identify the genesis and various iterations a policy can take as it makes its way to implementation and practice. Ball outlined five contexts of the policy process: policy influences; policy text production and policy practices/effects; policy outcomes and political strategies. Ball’s policy trajectory approach has been supplemented by scalar analyses that consider policy levels from global to local levels. Ledger, Vidovich, and O’Donoghue (2015) argued that in an era of accelerating globalisation, key policy processes are no longer confined within national boundaries and analysis needs to extend from global to national to local or institutional levels, with at times the addition of intermediate levels such as regional and state, depending on the particular policy. With this in mind, we considered the global policy contexts and looked for evidence of policy as discourse within the various state-based policy documents. This chapter specifically focusses on the first three contexts and trajectory levels. A series of research questions aligned to these contexts were developed to better understand the policy and practices involved across Australia.

The research questions applied across the texts, discourses and practices were:

-

1.

What are the main partnership themes emerging from the national initial teacher education policy documents?

-

2.

How do the national policies circulate in state-based initial teacher education policy documents?

-

3.

What are the commonalities and differences in the policy practices/effects across the four states?

-

4.

What are the longer-term policy implications of policies and practices on future teacher education partnerships?

In setting out the response to these four questions, the first and second questions are examined through document analysis at the national level and state level for each case and through discussion of the global trends currently impacting on Australia. The third and fourth questions are then considered by looking across the four cases in reference to policy-practice links and longer-term implications and recommendations.

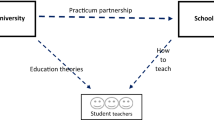

Teacher Education and the Partnership Policy Reform Agenda: Policy as Text

In recent decades across many countries, there have been political calls for greater involvement of schools and teachers in initial teacher preparation (see, for example Furlong, McNamara, Campbell, Howson, & Lewis, 2008). This has been largely expressed in the policy reform literature as school-university partnerships with the desire to both connect the perceived divide between theory and practice and promote professional development for teachers and teacher educators (Smith, 2016). Mattsson, Eilertsen, and Rorrison (2011) characterise this change as ‘a practicum turn in teacher education’ (p. 17). The focus on situated learning and its contribution to practice-based knowledge in the workplace (Lave & Wenger, 1991) and the need for connections between teacher education programs and schools to build quality teacher education (Darling-Hammond, 2000, 2006) identify a shift in the value of practice-based knowledge in teacher education. Reid (2011) similarly identifies the current reforms as a ‘practice turn’. While policy debates might focus on increasing the number of days for preservice teachers to spend in schools, Reid notes the importance of moving beyond measuring the number of days of professional experience within schools and calls for the return to a focus on practices that integrates and relates student experiences.

The exact forms of partnership work – and the associated ‘boundary crossings’ (Zeichner, 2010) for teachers and teacher educators as well as the professional learning involved for schools and universities – vary across time and international contexts and are often driven by specific policy changes. Ascribing stronger school-university partnerships as a path to improve teacher education, while an increasing feature of the political gaze, is not new in Australia. Many variations of school-university models and partnerships have been documented. (For a full historical analysis, see Vick, 2006.)

Despite the long-standing debates about the best models of teacher preparation and persistent reviews into teacher education (Louden, 2008; White & Forgasz, 2016), the concept of partnerships has become the focus of policymakers as a vehicle to resolve the issue of the perceived theory/practice divide that has long plagued teacher education. In this policy document analysis, we found that the document Quality Matters: Revitalising Teaching: Critical Times, Critical Choices (Ramsey, 2000) was a historical catalyst for renewed interest in strengthening school and university partnerships. Over almost two decades ago, this report advocated that a quality professional experience was central to an effective initial teacher education program which could only be realised through close partnerships between universities and schools. As a result of the report, the New South Wales Institute of Teachers (NSWIT) was established in 2004 under the Institute of Teachers Act with one of its objectives to advance the quality of initial teacher education (ITE) by assessing ITE programs against a set of rigorous requirements. One key requirement was that ITE programs must demonstrate how they ensured and supported high-quality professional experience within their teacher education programs.

The call for a National Partnership fund proposed at the time was answered by the Australian Government announcement through the National Partnership Agreement on Improving Teacher Quality (Council of Australian Governments, 2008) with the following priorities:

1. The systemic response to strengthening linkages between initial teacher education programs and transition to beginning teaching and teacher induction,

2. The professional learning implications of preservice teachers and in-service teachers working together as co-producers of knowledge (p. 4).

Over $550 million was provided for this initiative with $444 million directed to states and territories. A wide range of partnership programs was initiated during this time, though the language to describe partnerships differed across jurisdictions with each taking its own terminology. Across the life of the initiative, terms have included academies of practice, partnership schools, schools of excellence, centres of excellence and training schools. Partnerships between schools, sectors and universities were strengthened during this time and stronger links established between universities and work force planning sectors (Broadley, Ledger, & Sharplin, 2013; Ledger, 2015) resulting in a range of tripartite initiatives discussed later in the chapter.

Most recently the Australian Government has moved from incentivising partnerships to now mandating them (AITSL 2015, 2016) through the initial teacher education accreditation process. The recent Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) report and subsequent extensive policy ensemble, including Melbourne Declaration (MCEETYA, 2008), Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL, 2011), Australian Professional Standard for Principals, national curriculum, national teacher registration boards and national testing regimes for students in schools and in teacher education programs, are examples of this move. Louden (2015) suggests that the latest Australian policy assemblage resemble policy associated to what Sahlberg (2014) has termed ‘the Global Education Reform Movement’ (GERM). More recently, Dinham (2015) also expressed his concern that the GERM ‘are finding support and traction in Australia’ (p. 12).

Many of the case examples discussed later in this chapter had their roots in the first wave of new policy reform influenced by the Melbourne Declaration (2008) and National Partnership funding. The Melbourne Declaration (2008) was pivotal in establishing a national agenda where schools are central to the development and well-being of all young Australians and to the country’s social and economic prosperity. The second partnership policy wave has only recently occurred although various state-based jurisdictions have already taken up the policy discourse. Two particular documents heralded the increased focus on strengthened and mandated partnerships. The first is the recent review and report into initial teacher education, Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (TEMAG, 2015), and the second the new standards and procedures for the accreditation of initial teacher education providers and the accompanying guidelines (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2015, 2016). Amongst many other recommendations, the Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers report focusses on partnerships and the important work of the supervisor/mentor in improving initial teacher education. It states:

To ensure new teachers are entering classrooms with sufficient practical skills, the Advisory Group recommends ensuring experiences of appropriate timing; length and frequency are available to all teacher education students. Placements must be supported by highly-skilled supervising teachers who are able to demonstrate and assess what is needed to be an effective teacher. The Advisory Group strongly states that better partnerships between universities and schools are needed to deliver high quality practical experience. (TEMAG, 2015, p. 7)

The emphasis on placements, partnerships and supervising teachers outlined in the report is also found in international literature. It has long been recognised that in Australia, we are influenced by many of the past policies of the USA and England (Mayer, 2014; Gilroy, 2014). In England, for example, government legislation from 1992 onwards made it mandatory for initial teacher education (ITE) providers to offer preservice courses with schools, thus making partnership a ‘core principle of provision’ (Furlong, Barton, Miles, Whiting, & Whitty, 2000, p. 33). Menter, Hulme, Elliot, and Lewin (2010) and Conroy, Hulme, and Menter (2013) described the rise of teacher training schools, hub schools advanced in Scotland (Donaldson, 2011) or professional learning schools across a number of countries as part of the practice-based reform agenda.

School-University Partnerships: Policy as Discourse

As discussed earlier, the case examples below provide policy data related to four Australian states (New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia). The discussion is presented in four main sections that parallel the research questions noted earlier. A close examination of the policy trajectory is provided, and brief examples are also given in relation to practice.

Case: New South Wales

We argue earlier in the chapter that the Quality Matters (Ramsey, 2000) NSW report was the first of a formalised policy partnership response. As an outcome of the 2008 federal funding initiative, the New South Wales State Government established 50 schools as ‘centres of excellence’ (CoE). The CoEs were selected based on schools that had been seen to demonstrate increases in student learning outcomes based on standardised testing. Selected schools were then connected to a university with the purpose of sharing high-quality teaching practices between teachers, teacher education academics and preservice teachers, with preservice teachers being immersed in the CoE schools, observing high-quality teaching and experiencing high-quality supervision. The underpinning logic was that schools with excellent National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) results would be ideal sites for preservice teacher learning. This approach mirrors the views in the English ‘academy’ models where schools have been selected for teacher training on the basis of standardised results only. The concerns expressed in this approach is that preservice teachers are not participating in diverse schools and consequences reveal a shortage of teachers willing and prepared to work particularly in challenging environments.

The documented success of the 2009 Centres of Excellence initiative was limited to individual schools/university partnerships and a relatively small number of preservice teachers. As a response to this limitation and to societal concerns with broader teacher quality nationally, the New South Wales Government released Great Teaching, Inspired Learning-A Blueprint for Action (New South Wales Government, 2013), which was a policy response focussed on quality education for all students. The blueprint outlined 47 actions to ensure continual improvement in teaching and learning within NSW Schools. Great Teaching, Inspired Learning-A Blueprint for Action (GTIL) argued that professional experience was pivotal to the strengthening and improvement of teacher preparation and established a series of actions in respect to professional experience and university/school partnerships. For example, GTIL advocated for the establishment of partnership agreements between initial teacher education providers and schools and school systems, clarity of the roles and responsibilities for all stakeholders involved, an evidence guide to support the supervision of preservice teachers and common assessment of preservice teachers based on the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APST).

The Board of Studies Teaching and Educational Standards (BOSTES) published A Framework for High Quality Professional Experience in New South Wales Schools in June 2014. The framework detailed what initial teacher education providers must include within their professional experience programs. This included a formalised arrangement between the initial teacher education provider and school/schooling system; clarity around roles, responsibilities and processes for professional experience; and professional development for teachers supervising preservice teachers. The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (APST) is foundational to all documentation, assessment and professional learning.

The New South Wales Department of Education in 2015 committed to establishing professional experience agreements between universities and NSW Department of Education Schools. The Board of Studies Teaching and Educational Standards (BOSTES) Professional Experience Framework underpinned the agreements, and in October 2015, universities in NSW were partnered with what was described as a ‘hub school’. The formal partnership required the school (secondary or primary) and the university to work in a collaborative partnership to develop and trial an innovative professional experience program. The agreement was extended in May 2016 with each university partnered with an additional hub school. How this was to be fulfilled was not specified; rather universities with their hub school were to work together to implement and evaluate a range of models of professional experience and professional learning over a funding period of 2.5 years, with funding allocated to each hub school. Universities were not allocated funding.

This new 2015 professional experience agreement has some similarities to the 2009 Centres of Excellence (CoE) with university and schools working together to share quality teaching and learning practice, with the primary objective to strengthen professional experience practices. However, the new agreement added the expectation that universities and hub schools would build professional learning communities where research on innovations in teaching, learning and professional experience would be shared and professional development of mentor/supervising teachers would be supported. A new focus of this policy initiative was the expectation that research would be undertaken to inform further partnership development.

Case: Victoria

In Victoria, under the first partnership policy wave, the Victorian School Centres of Teaching Excellence (SCTE) (State Government Victoria, 2011a) were established, and funding was provided to universities in partnership with a cluster of schools. Unlike New South Wales, a much smaller number of centres or partnerships were formed, and universities were responsible for the distribution of funding and partnering. This key feature ensured an equal commitment existed from both school and universities throughout the partnership. The School Centres of Teaching Excellence (SCTE) funded seven centres each with a university and network or cluster of schools. In the Victorian case (unlike the Queensland example shared below), all schools in the first wave were state schools. Again, unlike NSW, the selection of schools involved was decided upon jointly by the universities and schools, and there were no criteria based on performance of schools in standardised tests. ‘Clusters’ of schools formed geographically enabling a far greater outreach and participation of schools and inclusion of schools in diverse contexts, for example, inner city, regional, rural and remote. While NSW moved to follow more English-based academy models, Victoria looked to both England and the USA with reference in the documentation to ‘residency models’ and ‘professional learning schools’.

The School Centres of Teaching Excellence (SCTE) discussion paper specifically referred to international policies in its rationale to move to school-university partnerships. The example below highlights reference to US policy documentation. Specifically the document states:

The US Federal Secretary of Education asserted that ‘America’s university-based teacher preparation programs need revolutionary change – not evolutionary tinkering’, and has subsequently led a national reform to restructure teaching as a practice-based profession similar to medicine or nursing. Student teachers will have a more closely-monitored induction period, followed up with ongoing professional development. The National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education is investigating ‘scalable ways to improve in-the-classroom training and strengthen relationships between school districts and the colleges and universities that prepare their teachers’. (State Government Victoria, 2011b, p. 5)

The second wave of partnership policy in Victoria has been named the Victorian Teaching Academies of Professional Practice (State Government of Victoria, 2015). It is interesting to note the change in terminology drawn from English school-led training models named ‘academies’. While this term is similar to the term used to describe school-led teacher education models in England, the focus has not been the same. Rather academies in the Victorian model have a focus to improve professional learning of mentors, improve assessment of preservice teachers and improve classroom practice. The Victorian Government’s From New Directions to Action: World Class Teaching and School Leadership (State Government of Victoria, 2013) states that:

An Academy will exist as a partnership of universities and schools and is designed to establish leading practice in providing quality pre-service teacher education, continuing professional learning and research opportunities. It will explore options for the delivery of pre-service teacher education with a school-based focus and the ways in which pre-service teachers are immersed in effective professional practice. (p. 1)

The second wave of policy reform has seen funding go to schools and not to universities making resourcing an issue. The seven academies that represent the school-university partnership has been extended to 12 with almost all Victorian universities involved and now including catholic schools as well as state schools.

Some of the key features of both waves have included clustering primary and secondary schools together so that teams of university-based and school-based colleagues can connect together. ‘Clusters’ are traditionally a group of schools located geographically together and connected with common professional learning foci. Benefits have been recorded (White & Forgasz, 2017) for a number of stakeholders including mentor teachers emerging as a key professional learning group. The authors’ note:

The dual focus on participants becoming research-informed mentors and thinking of themselves as school-based teacher educators was a key feature of this mentor professional learning program which enabled the development of a shared vision for teacher education that cut across school and university boundaries.

Case Study: Queensland

Queensland is a geographically large state with the majority of universities clustered in the lower south-east seaboard. Travelling long distances challenges the establishment and nurturing of mutually beneficial school-university partnerships. However, like the other states, Queensland has historically engaged with a range of different types of schools that are managed in different ways including faith-based schools, independent schools and public schooling. Partnerships’ programs between systems, groups of schools and initial teacher education institutions developed in very different ways across this broad schooling sector in Queensland. Partnerships between schools and higher education institutions were identified as important in The Review of Teacher Education and School Induction (Caldwell & Sutton, 2010a, 2010b). A sector-wide government policy A Fresh Start: Improving the Preparation and Quality of Teachers for Queensland Schools (2013a) articulated the development of partnerships as formal professional experience agreements that recognise the mutual contribution of schools and higher education institutions towards providing quality professional experience opportunities for initial teacher education students (Department of Education Training and Employment Queensland Government, 2014).

The focus of these agreements was to redress concerns that there were no formal requirements or agreements for schools to provide places for initial teacher education students to undertake placement (Department of Education Training and Employment Queensland Government, 2013b) even though there were accreditation mandates for higher education institutions that require placements to be undertaken in schools. The focus of this policy agenda was ‘on ensuring that all Queensland schools have access to the teaching workforce they need to boost student performance and ensure young Queenslanders are well-prepared for life after school’ (Department of Education Training and Employment Queensland Government, 2013b, p. 1). Unlike both previous examples, the federal government National Partnership agreement on improving teacher quality (Council of Australian Governments (COAG), 2008) agenda provided funding to support different models of engagement between schools and universities to emerge across the sector. Education Queensland focussed on the development of ‘centres of excellence’ in partnership with universities to extend the experience of high performing graduates with the aim of recruiting high-quality initial teacher education students for rural and remote schooling locations (Department of Education and Training Queensland Government, 2015). There was a strong agenda focussed on workforce planning in Queensland especially in relation to the provision of quality teachers for rural and remote schools.

One of the challenges identified by the development of partnerships was the burden on individual schools in the development of these agreements. In 2014, Independent Schools Queensland (ISQ) expanded their existing ‘centres of excellence in preservice training’ program to facilitate the development of partnership agreements between peak bodies, schools and initial teacher education providers. This is just one example of the second wave of partnership development. In Queensland, the second wave was supported by an analysis of enduring partnerships by the Queensland College of Teachers that identified four aspects of enduring partnerships: commitment to mutual learning, agreed and well-articulated roles and responsibilities, commitment to genuine collaboration and responsiveness between the partners (Rossner & Commins, 2012). On the basis of these findings, Independent Schools Queensland adapted their funded ‘centre of excellence program’ to include a partnership between Independent Schools Queensland, a university and schools for a period of 2 years. Schools were required to apply to host a centre of excellence and agree to engage with Independent Schools Queensland and a partner university. The work began with a draft service agreement between Independent Schools Queensland and the university.

To illustrate the complexity of partnership agreements, one university experience is discussed. The collaboration between the participants and genuine dialogue saw the service agreement develop into a partnership agreement that initially articulated the roles and responsibilities of Independent Schools Queensland and the university. Later this expanded to include the roles of the schools in the partnership. Funding support was provided directly to the schools in response to a project plan negotiated between the partners. The initial challenge for all parties was the negotiation of formal agreements in the context of the various institutions. The process began in August 2014 and concluded in December with 18 iterations of the agreement being exchanged. Upon reflection, the detailed and sustained conversations that the partnership negotiation represented provided a strong foundation for the work that followed and provided the groundwork for the team to maintain the responsiveness required to ensure this work contributed to the development of the quality teaching agenda. The focus within this partnership was the development of mutual learning as a contribution towards quality teaching for all the stakeholders’ preservice teachers, teachers, school leaders, Independent Schools Queensland (ISQ) staff and teacher educators from the university context. The agenda within the independent schooling sector was closely aligned with achieving the outcomes of the state government Fresh Start agenda, namely, developing effective partnerships that facilitated improving the professional experience for preservice teachers. This was achieved through a community of practice that explored practice analysis focussed on the professional standards for graduates and teachers that also supported teachers to make consistent judgements about preservice teacher performance while on professional experience.

Case Study: Western Australia

Western Australia is also a large state with specific rural and remote staffing needs. The five universities are also centralised in Perth, the state’s capital. Western Australia’s response to the National Partnership program was very much influenced by university leadership and access to funding. Across the state, all universities, public and private, were involved in establishing ‘training schools’ for preservice teachers. Western Australian use of the training terminology heralded a shift to an apprenticeship model drawing from English policy. The term ‘training schools’ was not embraced by many of the universities; however it was the term used to fulfil the nomenclature of the tender process in Western Australia. National Partnership funding was awarded to all universities, although three public universities, Murdoch University, Curtin University and the University of Western Australia, joined together to form the WA Universities Training Schools (WACUTS) program and worked collaboratively to offer a select entry internship for high-calibre final-year Bachelor of Education preservice teachers. Murdoch University, for example, led the WACUTS 12-month internship program. Interns were assigned as co-teachers at one school for the whole calendar year. The program graduated a total of 50 interns spanning Early Childhood Education, Primary and Secondary programs each year for 3 years (2010–2013) in rural and metropolitan contexts. Similarly, Edith Cowan University and University of Notre Dame offered a ‘residency program’ similar to the US model, specific to its Graduate Diploma cohort, and placed preservice teachers in two different schools over the year (one per semester) for 3 years (2010–2013). Over 100 preservice teachers graduated each year from the residency program.

Both WA Universities Training Schools program and the residency program were supported by a series of associated ‘training schools’. These schools were chosen based on their partnerships with the universities and their ongoing commitment and capacity to support preservice teachers over 6 months at a time (Residency) or 12 months (WA Universities Training Schools program). One unique aspect of the identified training schools for each program was their capacity to support interns from different universities. The program was well timed as the new policy reform for initial teacher education meant schools and universities were collectively grappling with the new Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL, 2011) and associated assessment requirements for preservice teachers. During this period of national policy reform, the tripartite relationship between universities, schools and education sectors was strengthened as each body worked together for a common goal of producing ‘classroom-ready’ graduates in response to the second wave of policy reform outlined in Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (TEMAG, 2015).

The legacy of National Partnership funding is a sustained commitment to internships in Western Australia by the department, universities and schools. Once funding ceased in 2013, the Department of Education continued its support for internships, offering financial support for secondary interns in areas of workforce planning needs, as well as professional support for early childhood and primary 12-month internships. However, only Murdoch University continued internships after funding ceased using the WA Universities Training Schools (WACUTS) program model as a blueprint. It has graduated approximately 40 high-calibre interns annually across programs and contexts since 2011. After a hiatus of 2–3 years, Edith Cowan University is currently redesigning a residency program, and the University of Western Australia and Curtin University are independently conceptualising or implementing different models of internships suitable for their programs. Identified ‘training schools’ in WA generated from the original National Partnership funding have continued to support preservice teachers across a range of placement types including internships, shorter-term ‘block’ or 3–6 week placements, distributed placements and more recently the employment-based model used by Teach for Australia (TFA) linking Victoria and Western Australia more closely.

In addition to National Partnership-funded training schools’ programs that targeted preservice teachers, the Department of Education has established nearly 70 Teacher Development Schools more akin to the NSW ‘centres’ with the sole purpose to guide teachers on curriculum content and professional standards outlined in the Australian Institute for Teaching and Learning (AITSL) suite of policy texts as part of the second wave of policy reform for teacher education. It is not surprising that these schools include many of the National Partnership Training Schools.

Findings and Discussion

The four case examples demonstrate both partnership policy convergence and divergence. All state-based policy initiatives aimed, to different degrees, to formalise agreements between schools and universities and provide some form of framework to guide their creation and sustainability. Frameworks for the types of partnerships were negotiated by the universities (as in the Victoria case) or more flexibly (as in New South Wales) where no one model of partnership was mandated; rather each hub school, centre or academy was encouraged to develop a partnership model based on their own specific needs and context. In Queensland, there were examples of both these levels of partnership being more prescribed to address the issue of availability of teachers to supervise professional experience placements and the more flexible partnership models such as the one developed across peak bodies, schools and university as partners.

The common aspect of each of the partnership cases presented is that resourcing was aligned with policy and funding and was for a set period of time. In all cases, funding supported personnel from university, schools and school systems to implement the envisaged government partnership policy. Such funding was key no matter how the funding was allocated, whether it be to schools, as in the case of New South Wales where an individual hub school was allocated funding over a specific time period, or in the case of Western Australia where university(s) submitted a tender to access funding to establish and support yearlong preservice internships at partnership schools. What cannot be disputed is for sustained partnerships, resourcing, money and committed personnel from all sectors involved in the partnership agreement are fundamental to success. Resourcing one component of the partnership and not the other does not appear to enable effective partnerships and relationships to flourish. Funding models in the future need to be allocated to both partners and specifically to the allocation of supporting the emergence of new roles and work accompanied in connecting and bridging the relationships between schools and universities.

Although the outcome for each of the policy cases presented was to establish effective school-university partnerships with a primary focus on enhanced professional experience for preservice teachers, each of the cases discussed is unique. In the case of Victoria and Queensland, a university was partnered with a number of schools to develop what may be viewed as a ‘community of practice’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Rossner & Commins, 2012). In contrast, New South Wales partnership policy required a university to be partnered initially with only one school, with the aim to develop an integrated mentoring-professional experience model.

In both the case of Western Australia and New South Wales, the government university-school partnership policy was built on pre-existing relationships between a university and particular school(s). In these cases, the state policymakers enacted policy that built on what was in most cases an informal university-school partnership. While in the case of Queensland, the state-driven partnerships were new and provided an opportunity to secure commitment from the profession to support quality preservice teacher professional experience placements. The enactment of this policy as the development of a future workforce had a significant impact on the engagement of schools in professional experience. The smaller-scale partnership agreements successfully shifted more of the focus on the need for genuine collaboration and mutual learning possible in authentic partnerships as a contribution towards the quality teaching agenda.

There are long-term implications that can be garnered from our initiative to present the comparison of the four cases. Firstly, there is no one effective partnership model that can be applied to all jurisdictions. Future government policy reforms need to acknowledge and support the flexibility between universities and schools all of which have unique contexts. In these cases to date, a ‘cluster’ model was more effective in enabling cross-institutional collaboration and a collegial approach to linking preservice and in-service professional learning. It also appears important that all schools, not just those who have high NAPLAN results, should have the opportunity to participate in initial teacher education with preservice teachers. Schools can benefit from working with a university in multiple ways including opportunities for professional learning and research. Likewise universities can benefit by connecting with practitioners and drawing on their professional expertise in curriculum renewal. Most importantly preservice teachers benefit from diverse settings and contexts and being a part of a professional learning community. As the partnership policy is extended, we strongly encourage models that will further enable rural, regional and remote schools to be included and for any policy development to be wary of a metropolitan-centric partnership model by default. Any new cluster models with rural and remote schools could be enabled through technology, and innovative approaches should be welcomed.

Another finding garnered from our data suggests that continued funding is required to support long-term development and the sustainment of partnership programs. Once funding ceases, partnerships often dissolve, as seen in the Western Australian case where only one university and their partnership schools continued to offer an extended internship program. Aligned with funding is the need to have personnel at schools, university and government that are committed to school-university partnerships and who have a deep understanding of each sector and the complexities of integrating educational bodies whose structures and purpose may be difficult to align. The need for research as part of the policy reform agenda that is theoretically based has been largely ignored within current government policy thus far, as most funding has supported only the implementation of the partnership innovation itself. Research is seldom funded as part of the initiative, and the long-term outcomes of the quality teaching agenda remain under-researched. This raises the important need for research on school-university partnerships to be central to policy agreements. It is the authors’ experience that the assembling and contrasting of the research on small-scale university-school partnerships can inform further policy and partnership initiatives (White, 2016), consistent with the aim of this chapter.

Conclusion

This chapter provides a review of policy texts, discourses and practices related to two waves of policy reform impacting initial teacher education in Australia. It emphasises the importance of partnerships in schools and universities as a result of the National Partnership Agreement of Improving Teacher Quality Report (2009–2013). The chapter highlights the importance of contexts and reveals variability in policy outcomes across the states in response to recent reform – in so doing exposing a range of opportunities and challenges for key stakeholders across all the sectors. The opportunities presented across the case studies relate primarily to partnership types, access, participation and re-culturation of the ways in which schools and universities can partner together, whereas the challenges relate to sustainability, equity and scalability. While supporting the traditional partnership approach that relies on individual connections between schools and universities, the variability across the states and even within states calls for a more strategic systems’ level approach to defining, monitoring and maintaining partnerships (see Le Cornu, 2015). But conversely, it recognises the need to allow for flexibility and diversity of partnership types across Australian jurisdictions to ensure a truly equitable model for all.

Partnerships between university and schools facilitated the enactment of the National Partnership initial teacher education policy reform in Australia; more importantly ‘tripartite relationships’ developed between university, school and education sectors within individual states during the recent wave of policy implementation. These partnerships resulted in cross-systems’ level approaches to program development and resulted in sustainability with stronger and more direct links to issues surrounding workforce planning (Ledger, 2015). This ‘shared responsibility’ and systems-based integrated approach to initial teacher education are also a recommendation in the TEMAG report (2014) from which the policy text Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (2015) was generated. However, building inter-institutional collaborations is labour intensive (Zeichner, Payne, & Brayko, 2015) and relies on changing the institutional culture and restructuring of current practices (Le Cornu, 2015).

Teacher education and the partnership policy reform agenda have produced a suite of new policies ‘as text’ and associated ‘policies as practice’ (Ball, 2015). The recommendations that emerge from this study relate not to the types of partnerships that were developed during the National Partnership policy reform but rather focus on the outcomes of the partnerships that were established. The outcomes show variability and diversity related to success, recognition and sustainability of partnership programs. It also highlights the need for further funded research in this space.

References

Aspland, T. (2006). Changing patterns of teacher education in Australia. Education Research and Perspectives, 33(2), 140.

Australian Government (2015). Action now: Classroom ready teachers – Australian Government Response. Retrieved from http://docs.education.gov.au/node/36789

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2011). Australian professional standards for teachers. Retrieved from http://www.aitsl.edu.au/australian-professional-standards-for-teachers

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2015). Accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia: Standards and procedures. Retrieved from http://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/initial-teacher-education-resources/accreditation-of-ite-programs-in-australia.pdf

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2016). Guidelines for the accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia. Retrieved from http://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/initial-teacher-education-resources/guidance-for-the-accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-in-australia.pdf

Bahr, N., & Mellor, S. (2016). Building quality in teaching and teacher education. Melbourne, Australia: ACER. Retrieved from http://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1025&context=aer

Ball, S. (1994). Education reform: A critical and post structural approach. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Ball, S. J. (2005). Education policy and social class : The selected works of Stephen Ball. London: Routledge.

Ball, S. J. (2015). What is policy? 21 years later: Reflections on the possibilities of policy research. Discourse Studies in the Cultural Politics of. Education, 36(3), 306–313.

Board of Studies Teaching and Educational Standards (BOSTES). (2014). Professional experience framework. Retrieved June, 2016, from http://nswteachers.nsw.edu.au/taas-schools/principals-supervisors/professional-experience-framework/

Broadley, T., Ledger, S., & Sharplin, E. (2013). New frontiers or old certainties: The pre-service teacher internship. In D. Lynch & T. Yeigh (Eds.), Teacher education in Australia: Investigations into programming, practicum and partnerships (pp. 94–108). Tarragindi, Australia: Oxford Global Press.

Caldwell, B., & Sutton, D. (2010a). Review of teacher education and school induction, First report. Retrieved from http://flyingstart.qld.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/review-teacher-education-school-induction-first-full-report.pdf

Caldwell, B., & Sutton, D. (2010b). Review of teacher education and school induction, Second report. Retrieved from http://education.qld.gov.au/students/higher-education/resources/review-teacher-education-school-induction-full-report.pdf

Centres of Excellence. From http://education.qld.gov.au/staff/development/pdfs/tece-factsheet.pdf

Conroy, J., Hulme, M., & Menter, I. (2013). Developing a model for teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 39(5), 557–573.

Council of Australian Governments (COAG). (2008). National partnership agreement on improving teacher quality. Retrieved from http://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/default-document-library/national_partnership_on_improving_teacher_quality

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education policy analysis archives, Vol. 8 (1). Tucson, AZ: College of Education.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300–314. doi:10.1177/0022487105285962.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2011). School centres for teaching excellence. Retrieved from http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/programs/partnerships/schoolcentresteachexcelfactsheet.pdf

Department of Education and Training Queensland Government. (2015). Teacher education.

Department of Education Training and Employment Queensland Govnerment. (2013a). A fresh start: Improving the preparation and quality of teachers for Queensland schools. Retrieved from http://flyingstart.qld.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/A-Fresh-Start-strategy.pdf

Department of Education Training and Employment Queensland Government. (2013b). A fresh start professional experience partnership agreements. Retrieved from http://flyingstart.qld.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/factsheet-fresh-start_Prof-Exp-Agreements.pdf

Dinham, S. (2015). The worst of both worlds: How U.S and U.K models are influencing Australian education. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23(49), 1–20. Retrieved from http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/viewFile/1865/1615.

Donaldson, G. (2011). Teaching Scotland’s future: Report of a review of teacher education in Scotland. Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Government APS Group.

Fitzgerald, T., & Knipe, S. (2016). Policy reform: Testing times for teacher education in Australia. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 48(4), 358–369. doi:10.1080/00220620.2016.1210588.

Furlong, J., Barton, L., Miles, S., Whiting, C., & Whitty, G. (2000). Teacher education in transition: Reforming professionalism. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Furlong, J., McNamara, O., Campbell, A., Howson, J., & Lewis, S. (2008). Partnership, policy and politics: Initial teacher education in England under new labour. Teachers and Teaching, 14(4), 307–318.

Gilroy, P. (2014). Policy intervention in teacher education: Sharing the English experience. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(5), 622–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2014.957996.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Le Cornu, R. (2015). Key components of effective professional experience in initial teacher education in Australia. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership.

Ledger, S. (2015). Don’t follow the Americans on teacher education policy reform. Online Opinion- Australia’s e-journal of social and political debate 8th September, 2015. http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=17656

Ledger, S., Vidovich, L., & O’Donoghue, T. (2015). International and remote schooling: Global to local curriculum policy dynamics in Indonesia. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(4), 695–703. doi:10.1007/s40299-014-0222-1.

Louden, W. (2008). 101 Damnations: The persistence of criticism and the absence of evidence about teacher education in Australia. Teachers and Teaching, 14(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802037777.

Louden, W. (2015, July). Mentoring in teacher education (Centre for Strategic Education, Seminar Series Paper No. 245). Victoria.

Mattsson, M., Eilertsen, T. V., & Rorrison, D. (2011). A practicum turn in teacher education. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publisher.

Mayer, D. (2014). Forty years of teacher education in Australia: 1974–2014. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(5), 461–473. doi:10.1080/02607476.2014.956536.

Menter, I., Hulme, M., Elliot, D., & Lewin, J. (2010). Literature review on teacher education in the 21st century. Edinburgh, UK: Education Analytical Services, Schools Research, Scottish Government.

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs MCEETYA. (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). (2010). Transforming teacher education through clinical practice: A national strategy to prepare effective teachers. Retrieved from http://www.ncate.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=zzeiB1OoqPk%3D&tabid=7

New South Wales Government. (2013). Great teaching, inspired learning. Sydney, Australia: NSW Government.

Ramsey, G. (2000). Quality Matters. Revitalising teaching: Critical times, critical choices. Retrieved from https://www.det.nsw.edu.au/teachrev/reports/reports.pdf

Reid, J. A. (2011). A practice turn for teacher education? Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 293–310. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2011.614688.

Rossner, P., & Commins, D. (2012). Defining ‘enduring partnerships’: Can a well-worn path be an effective, sustainable and mutually beneficial relationship? Retrieved from http://www.qct.edu.au/PDF/DefiningEnduringPartnerships.pdf

Sahlberg, P. (2014). Facts, true facts and research in improving education systems, paper presented to the British Education Research Association, London, 21st May.

Smith, K. (2016). Partnerships in teacher education – Going beyond the rhetoric, with reference to the Norwegian context. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 6(3), 17–36.

State Government Victoria. (2011a). School centres for teaching excellence. Retrieved from http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/programs/partnerships/schoolcentresteachexcelfactsheet.pdf

State Government Victoria. (2011b). School centres for teaching excellence: Discussion paper. Retrieved from http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/programs/partnerships/discussionpaper.pdf

State Government Victoria. (2013). From new directions to action: World class teaching and school leadership. Retrieved from http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/teachingprofession.pdf

State Government Victoria. (2015). Teaching academies of professional practice. Retrieved from http://www.education.vic.gov.au/about/programs/partnerships/Pages/tapp.aspx.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). (2015). Action now: Classroom ready teachers. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government.

Vick, M. (2006). “It’s a difficult matter”: Historical perspectives on the enduring problem of the practicum in teacher preparation. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(2), 181–198. doi:10.1080/13598660600720579.

White, S. (2016). In R. Brandenburg, S. McDonough, J. Burke, & S. White (Eds.), Preface in teacher education: Innovation, intervention and impact. Singapore, Singapore: Springer.

White, S., & Forgasz, R. (2016). The practicum: The place of experience? In J. Loughran & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International handbook of teacher education. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

White, S., & Forgasz, R. (2017). Supporting mentoring and assessment in practicum settings: A new professional development approach for school-based teacher educators. In M. A. Peters, B. Cowie, & I. Mentor (Eds.), A companion to research in teacher education. Singapore, Singapore: Springer.

Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-009-9141-1.

Zeichner, K., Payne, K.A., & Brayko, K. (2015). Democratising teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(2), 122–135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

White, S., Tindall-Ford, S., Heck, D., Ledger, S. (2018). Exploring the Australian Teacher Education ‘Partnership’ Policy Landscape: Four Case Studies. In: Kriewaldt, J., Ambrosetti, A., Rorrison, D., Capeness, R. (eds) Educating Future Teachers: Innovative Perspectives in Professional Experience. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5484-6_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5484-6_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-5483-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-5484-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)