Abstract

Readiness for change is defined as a cognitive precursor to resistance or as a support for a change effort. The main objective of this literature review is to explore readiness for change at the individual and organizational levels. It reviews publications to trace readiness for change. It provides a picture of the concept of readiness for change, explores and identifies the relationships between the readiness for change , individual change , and organizational change and the challenges of change. Dealing with the complex nature of change is the greatest challenge when following through and sustaining a change initiative. Leaning on institutional theory , it contextualizes the concept of readiness for change in Ethiopia .

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Increasing global competition and changing political ideologies are some of the reasons for the accelerated rate of organizational change (Armenakis et al. 1999). Organizational change is considered unavoidable (Drucker 1999), and its rate is assumed to be constantly increasing. To cope with this global phenomenon, employees in organizations must be ready for change more than ever before. If people are not ready for change, they will resist it (Lewin 1945; Prochaska et al. 1994). If people resist a change plan, the planned change will not have a chance to succeed. The key question for change agents is how people get ready for change in their environment in a way that they are ready to implement effective changes in their organization (Walinga 2008).

Readiness refers to an organization’s members’ change commitment and change efficacy to implement organizational change (Weiner et al. 2008, 2009). The ordinary definition of the term ‘readiness’ connotes a state of being both psychologically and behaviorally prepared to act (i.e., willingness and ability). Readiness for change is defined as ‘the cognitive precursor to the behaviors of their [employees] resistance to or support for change efforts’ (Armenakis et al. 1993: 681–682). Readiness for change embodies individuals’: (1) beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding the extent to which the change is needed, and (2) perceptions about the organization’s ability to deal with change under dynamic business conditions. Change refers to making something different from its initial position and involves confrontation with the unknown and loss of the familiar (Agboola and Salawu 2011). The goal of intentional change typically addresses and helps make rapid improvements in economic value while simultaneously creating an organization whose structure, processes, people, and culture are tailored appropriately for its current mission and environment, and it is positioned to make the change (Beer and Nohria 2000).

The main objective of this review is to explore readiness for change at the individual and organizational levels. In addressing this objective, it answers the following questions:

-

1.

What are the descriptions of readiness as an antecedent of change?

-

2.

What does readiness for change mean at the individual and organizational levels, respectively?

-

3.

How does readiness for change among employees emerge over time?

-

4.

What kind(s) of individual and organizational readiness supports change?

2 Background

Readiness for change is not automatic, and it cannot be taken for granted. A failure in readiness for change may result in managers spending significant time and energy dealing with resistance to change (Smith 2005). Further, as per Smith (2005), if readiness for change is important, how then might this best be accomplished? The most common key steps are as follows: creating a sense of need and urgency for change, communicating the change message and ensuring participation and involvement in the change process, and providing anchoring points and a base for achieving the change.

Change is all about managing the most important and complex assets of an organization—its people. It is people who make up organizations, and it is they who are the real source of, and vehicle for, change. They are the ones who will either embrace or resist change. If organizational change is meant to thrive and succeed, then the organization and its people must be geared for such a transformation (Smith 2005). Dealing with the complex nature of human beings is the greatest challenge within a change initiative to sustain the change. If not, it is very easy for an organization to fall back into old habits. It takes time and conscientiousness to change an organizational culture. People need to get ready to implement and reinforce the upcoming organizational change efforts. Change is needed for an organization to integrate and align people, processes, culture, and strategies (California State 2014). Therefore, we need to implement organizational changes continuously and thoroughly as the need arises. And there is a need for readiness for change.

This review deals with readiness for change , and it does so from an institutional theory perspective by exploring how readiness for change can be re-conceptualized at the individual and organizational levels (micro- and meso-levels). ‘Such an approach opens opportunities to highlight the ways in which actors utilize discursive tools, specifically skillful development of rhetorical argumentation, as instruments of power that can shape their constituents’ readiness for change’ (Amis and Aissaoui 2013: 73). In doing so, it makes key contributions to an understanding of readiness for change. Besides, according to Amis and Aissaoui (2013: 73), institutional theory ‘offers opportunities to develop theoretical frameworks that will allow for the exploration of how change readiness can be re-conceptualized as a process that is dialectically shaped within a given context, rather than a discrete and largely constant state.’

This chapter calls for shifting the locus of meaning to the individual and the overall (organizational) context in which the meaning is made. This recognizes that individuals’ cognitions are shaped by broader social institutions and the organization’s environment. Assessing readiness for change through an examination of the organizational environment that shapes such processes is likely to offer important insights into how change proceeds. There is a high risk of failure if individual and organizational readiness for change is lacking. Assessing the overall change readiness before any attempt to implement change begins is a good investment and one that can either reveal a path to success or give warnings of problems that may derail attempts at achieving change (Smith 2005). There is thus a need to identify organizational actions that make employees ready for change (Cinite et al. 2009).

It is important to uncover readiness for change from the Ethiopian perspective and identifying its implications for practitioners and policymakers. Readiness for change is a central strategic management issue and an organization requires a strategy to develop and maintain satisfied, committed, and loyal customers. Its significance is at the heart of the employee, customer, and supplier relationship for organizations to thrive. Increasing competitive pressures on both private and public organizations in Ethiopia have made readiness for change an important area of research in the field of management. The Ethiopian government is urging its public servants and officials to adjust themselves as per the demands of the business society and other international contemporary developments. Hence, Ethiopian officials are expected to take into account research outputs for forming and implementing policies.

3 Readiness for Change

In order to grasp the concept of readiness for change, it is important to explore, understand, and identify the relationships between readiness for change (at individual and organizational levels) and the challenges of change as they are currently viewed in existing literature. Readiness takes its roots in early research on organizational change (Schein and Bennis 1965). Perhaps the greatest challenge of change lies in the common assumption in organization change literature that employees need to ‘be made ready’ for the change that is imminent within an organization (Armenakis and Harris 2002). Change readiness has generally focused on individual cognition, that is, beliefs, attitudes, and intentions toward a change effort. ‘It is the cognitive precursor to the behaviors of either resistance to, or support for, a change effort’ (Armenakis et al. 1993: 681–682).

Increasing employees’ decisional latitude, participation, and power often requires a change in the managerial approach from authoritative to participative (Antonacopolou 1998). Perhaps more important than facilitating employee readiness for change would be exploring how leaders can prepare their employees’ readiness for change. Experiments in creating readiness for change involve proactive attempts by a change agent to influence the beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and ultimately the behavior of organizational members. At its core, it is believed that readiness for change involves changing individual cognitions (Bandura 1982; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975).

Armenakis et al. (1999) offer five different elements necessary for creating readiness : The first is the need for change. This is identifying a gap between a desired state and the current state. Quite simply, a change leader must justify the need for change. For example, providing information that shows that the organization’s product no longer meets customer expectations can make organizational members see that the current way of making the product is no longer acceptable. The second element for creating and managing readiness is establishing if the proposed change is the right change to make. The role of a change leader in this instance is to demonstrate that the proposed change is the right solution for eliminating the gap between the current and the ideal state. By demonstrating that and replacing an old service with a new, improved service will lead to an increase in revenues, instead of a continued decline, provides evidence that this change in service is the right thing to do.

The third element focuses on bolstering the confidence of organizational members, reinforcing that they can successfully make the change (Armenakis et al. 1999). Sometimes known as efficacy, this confidence comes from both experience and persuasive communication by change leaders. These leaders need to first emphasize that organizational members have the relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities to implement the change or that they will be given the opportunity to develop these. Further, they need to ensure that the organization has the relevant organizational structure, policies, procedures, technology, and management talent in place to successfully implement the change. Next is key support which involves actual organizational support for the change. The person supporting the change may, in certain circumstances, carry as much weight as the proposed change. Organizational members, when faced with a change, consider the position of both formal and informal leaders in an organization. If a change leader can enlist those formal and informal leaders in support of the change, other organizational members may also begin to adopt the change (Armenakis et al. 1999).

The final element is designed to answer the question, ‘What’s in it for me/us?’ (Armenakis et al. 1999). Organizational members not only want to understand the nature of what the outcomes of implementing the change might be, but they also seek to understand whether these outcomes will be positive or negative, and, if so, what the significance of the outcomes will be in terms of what each organizational member values. It is important to understand that the value of an outcome can carry as much weight as whether or not the outcome is negative or positive. For example, a change that results in an organizational member being promoted might be viewed as negative because of the requirement that he or she must uproot his/her family and relocate. The dislocation outweighs the positive gain in title and pay. It would be the change leader’s responsibility to guide the organizational member to embrace the change rather than resist it (Armenakis et al. 1999). Thus, the process must target creating readiness for change and not attempting to overcome resistance to it. By effectively creating and managing readiness, a change leader attempts to shape attitudes toward the change.

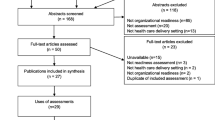

According to Goodstein and Burke (1995), organizational change can occur at three levels: (1) Changing the individuals who work in an organization, that is, their skills, values, attitudes, and eventually behavior but making sure that such individual behavioral change is always regarded as instrumental for organizational change; (2) Changing various organizational structures and systems—reward systems, reporting relationships, work design, and so on; and (3) Directly changing the organizational climate or interpersonal style—how open people are with each other, how conflict is managed, how decisions are made, and so on. Figure 1 shows the dimensions of individual and organizational change and their assumed relation to an organization’s performance.

4 The Challenge of Change

Changing behavior at both the individual and organizational levels means changing habitual responses and producing new responses that feel awkward and unfamiliar to those involved; therefore, it is easy to slip back to the familiar and comfortable (Goodstein and Burke 1995). Hence, successfully implementing change inevitably requires encouraging individuals to enact new behaviors so that the desired change is achieved (Armenakis and Bedeian 1999: 304). However, most change programs do not work because they are guided by change that is fundamentally flawed. This is because organizational change poses many challenges for employees, managers, and organizations (Walinga 2008). A common belief is that the place to begin is with individuals’ knowledge and attitudes. Changes in individual behavior, repeated by many people, will result in organizational change.

One way to think about the challenge is in terms of three interrelated factors required for corporate revitalization (Beer et al. 1990). Coordination or teamwork is especially important if an organization is to discover and act on cost, quality, and product development opportunities. The production and sale of innovative, high-quality, and low-cost products (services) depends on close coordination among marketing, product design, and manufacturing departments, as well as between labor and management. High levels of commitment are essential for the effort, initiative, and cooperation that coordinated action demands. New competencies such as business analytical and interpersonal skills are necessary if people are to identify and solve problems as a team. If any of these elements are missing, the change process is likely to break down (Beer et al. 1990).

A change initiative must be conducted in a way that it demonstrates the trustworthiness of the attempted change effort. Even when managers accept the potential value of a program for others, for example, quality circles to solve a manufacturing problem, they may be confronted with more pressing business problems such as new product development which takes up all their attention. According to Beer et al. (1990: 7), ‘one-size-fits-all change programs take energy away from efforts to solve key business problems- which explains why so many general managers do not support programs, even when acknowledging that their underlying principles may be useful.’ This is similar to an Ethiopian proverb ‘Chamakasya maere egirka,’ meaning every individual must wear a shoe of his/her size. In other words, every person must wear his/her size regardless of his/her desire, otherwise the result might be unwanted. Hence, each organization must strive to implement a change program that is tailored to its requirements.

Finally, challenges associated with change also require a process of cognitive appraisal to determine whether an individual believes he or she has the resources to respond effectively (Folkman and Lazarus 1988; Lazarus and Folkman 1987). Appraisal literature explains the response or ‘coping’ processes in terms of problem-focused coping or emotion-focused coping (Folkman and Lazarus 1980; Lazarus and Folkman 1985; Lazarus and Launier 1978). This is also referred to as active and passive coping styles (Jex et al. 2001). In addition, approach and avoidance style measures of coping also exist (Anshel 1996). When faced with a challenge, an individual primarily appraises the challenge as threatening or nonthreatening and secondly appraises the challenge in terms of whether he or she has the resources to respond to it effectively.

If an individual does not believe that he or she has the capacity to respond to challenges or feels a lack of control, he or she might turn to an emotion-focused coping response such as wishful thinking (‘I wish I could change what is happening or how I feel’), distancing (‘I’ll try to forget the whole thing’), or emphasizing the positive (‘I’ll just look for the silver lining, so to speak; try to look at the bright side of things’) (Lazarus and Folkman 1987). If an individual feels that he or she has the resources to manage the challenge, he or she will usually develop a problem-focused coping response such as an analysis (‘I try to analyze the problem to understand it better; I’m making a plan of action and following it’) (Lazarus and Folkman 1985). It is theorized and empirically demonstrated that one’s secondary appraisal determines the coping strategy (ibid).

Change initiatives for performance improvement and achieving competitive advantages have experienced several problems (Denton 1996; Lawson 2003). Up to 70% of all major corporate changes fail (Washington and Hacker 2005). Reasons for the shortcomings of change programs have been documented for decades. One long-known explanation for unsuccessful change initiatives is the management’s tendency to seek a quick fix solution instead of taking a longer term perspective (Kilman 1984). Another long-known reason for lack of success for a change is the propensity for organizations to implement piecemeal solutions rather than taking a systems perspective (Ackoff 1974). Another key causal factor of unsuccessful change is employees’ perception that the organization is not ready for the change and consequently there is lack of acceptance of it (Armenakis et al. 1993; Walinga 2008).

5 Institutional Theory and Change

This chapter uses institutional theory as a theoretical framework to see and explore how readiness for change can be re-conceptualized. Such an approach opens up opportunities to highlight the ways in which actors utilize discursive tools, specifically skillful development of rhetorical argumentation as instruments of power that can shape their constituents’ readiness for change (Amis and Aissaoui 2013).

Institutional theory is perhaps the dominant approach for understanding organizations (Greenwood et al. 2008). Institutionalization is the process by which ‘social processes, obligations, or actualities come to take on a rule-like status in social thought and action’ (Meyer and Rowan 1977: 341). Something is ‘institutionalized’ when it has a rule-like status. Institutionalization means that ‘alternatives may be literally unthinkable’ (Zucker 1983: 5). Further, institutional theory focuses on the deeper and more resilient aspects of social structure. It emphasizes the processes by which structures, including schemas, rules, norms, and routines, become established as authoritative guidelines for social behavior (Amis and Aissaoui 2013).

Institutional theory has traditionally focused on macro, field-level processes; increasing attention is, however, being accorded to advancing an understanding of the ways in which individuals’ perceptions are shaped within a given institutional environment (Scott 2008). This phenomenon, referred to as structured cognition, is a ‘very useful idea [that] reminds us that the interaction of culture and organization is mediated by socially constructed mind, that is, by patterns of perception and evaluation’ (Selznick 1996: 274).

The cultural cognitive approach is a major contribution of new institutionalism (Scott 2008), as it allows for a better understanding of the ways in which cognitions are influenced, shaped, given stability, or challenged by higher contextual factors such as group membership (Kilduff 1993; Simon 1945) and the broader institutional environment. Therefore, an institutional perspective can enrich our understanding of readiness for change by examining those institutions that individuals primarily build upon to make sense of their environment. This will further allow us to address calls for examining change readiness in the context of a given environment (Amis and Aissaoui 2013: 74).

6 How Do Organizations Get Ready for Change?

Organizational change can occur in more than one way (Goodstein and Burke 1995). ‘Change readiness strategies cite the individual’s need for perceived control as a determinant of readiness participation’ (Walinga 2008: 339). Change agents tend to rely on control factors when managing change and control-oriented words regularly appear in much of the change management literature: influence, advantage, persuade, convince, pressure, change, reengineer, manage, reorganize, merge, restructure, redirect, and mandate (Walinga 2008).

It is normal for people to resist change. Nevertheless, among the things that organizations can do is reduce resistance and establish some momentum (Martin 2013). Some of the mechanisms to reduce resistance include selecting positive people to run projects, providing valid information and explaining reasons, avoiding coercion and treating everybody honorably, sharing decision-making, listening and getting reactions, not over-reacting to the feedback, selling the benefits but not over-selling them, minimizing social change, rewarding those who change, particularly the trailblazers, and reviewing and if necessary modifying the approach based on what you learn.

7 Conclusions and Future Research

Readiness for change comprises different key components. Change is all about managing the most important and complex asset of an organization, its people. Dealing with the complex nature of human beings constitutes the greatest challenge for change initiatives to be followed through and sustained. It is easy for an organization to fall back into old habits.

Most people in organizations will belong to one group or a number of different groups, some formal and several informal. According to Jackson and Schuler (1995) and Armstrong (2009), these small groups may also fall somewhere in between the highly resistant to highly receptive spectrums. Within these groups, there will be leaders and followers. Leaders have a major influence on whether their group will respond positively to a proposed change. Group leaders are catalysts in building early momentum in a change project. To do so, leaders in organizations must have a clear sense of direction of the change initiative. More importantly, the leader’s style and approach is one of the most crucial elements in readiness for change.

Successful organizations continually transform themselves as they respond to, or anticipate, a changing environment. When planning for change, a leader needs to consider the short-term risk to the organization, the expected resistance, the holders of power, and the magnitude of commitment needed (Martin 2013).

Successful organizational change requires a visionary leadership. Further, according to Armstrong (2009: 433), ‘the achievement of sustainable change requires strong commitment and visionary leadership from the top.’ Hence, it is unlikely that a change leader can do everything, and so an energetic and committed team who will help to both lead and manage the change program needs to be established. This means all staff members at all management levels must be cooperative, participative, and optimistic about achieving readiness for a change agenda that arises from the leaders or the top management team.

The purpose of this chapter was to explore readiness for change at the individual and organizational levels, and it shows how the concept of readiness for change is dealt with in the developed world. The practical applicability of this theoretical development is less relevant in the Ethiopian context since the concept of readiness for change in not yet contextualized in Ethiopia. On the one hand, the governmental rhetoric is meant to get Ethiopian businesses to comply with international contemporary developments. On the other hand, the Ethiopian culture, seemingly institutionalized with its collective thinking among the Ethiopian people, is that status quo is better than change. This may be one of the biggest hurdles to readiness for change. There is a popular proverb in Ethiopia : ‘Kabiya leytifelto mel’akis, litifelto seytan,’ meaning that a known devil is better than an unknown angel. This proverb indicates that the level of readiness for change among the Ethiopian people is low. So, to mitigate resistance to new developments, the Ethiopian context needs separate attention where it is important to include several levels of analysis in order to assess how readiness for change is understood and practiced at individual, organizational, and governmental levels. Institutional theory , encompassing these levels and the broader institutional environment (cf. Amis and Aissaoui 2013; Kilduff 1993; Simon 1945), could lead such research in Ethiopia in a relevant direction. To contextualize culture and its influence on readiness for change is one example. This is, in turn, a huge challenge since Ethiopia has a number of ethnic minorities. Such studies would, however, be a first step in assisting policymakers and practitioners to enhance readiness for change in their respective organizations.

References

Ackoff, R.A. 1974. Redesigning the future: A systems approach to societal problems. New York: Wiley.

Agboola, A.A., and R.O. Salawu. 2011. Managing deviant behavior and resistance to change. International Journal of Business and Management 6 (1): 235–242.

Amis, J.M., and R. Aissaoui. 2013. Readiness for change: An institutional perspective. Journal of Change Management 13 (1): 69–95.

Anshel, M.H. 1996. Coping styles among adolescent competitive athletes. Journal of Social Psychology 136: 311–323.

Antonacopolou, E. 1998. Developing learning managers within learning organizations. In Organizational learning and the learning organization: Developments in theory and practice, eds. M. Easterby-Smith, L. Araujo, and J. Burgoiyne, 214–242. London: Sage.

Armenakis, A.A., and A.G. Bedeian. 1999. Organizational change: A review of theory and research in the 1990s. Journal of Management 25 (3): 293–315.

Armenakis, A.A., and S.G. Harris. 2002. Crafting a change message to create transformational readiness. Journal of Organizational Change Management 15: 169–183.

Armenakis, A., S. Harris, and K. Mossholder. 1993. Creating readiness for organizational change. Human Relations 46: 681–703.

Armenakis, A.A., S.G. Harris, and H.S. Feild. 1999. Making change permanent: a model for institutionalizing change interventions. In Research in organizational change and development, ed. W. Passmore, and R. Woodman, 289–319. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Armstrong, M. 2009. Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice, 11th edition.

Bandura, A. 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist 37: 122–147.

Beer, M., and N. Nohria. 2000. Cracking the code of change. Harvard Business Review 78: 133–141.

Beer, M., R.A. Eisenstat, and B. Spector 1990. Why change programs do not produce change. Harvard Business Review. Nov–Dec 1–12.

California State. 2014. Organizational change management: Readiness guide, Version 1.1.

Cinite, I., L.E. Duxbury, and C. Higgins. 2009. Measurement of perceived organizational readiness for change in the public sector. British Journal of Management 20: 265–277.

Denton, K. 1996. 9 ways to create an atmosphere of change. Human Resource Magazine 41 (10): 76–81.

Drucker, P.F. 1999. Management challenges for the 21st century. New York: Harper business.

Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Folkman, S., and R.S. Lazarus. 1980. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 21: 219–239.

Folkman, S., and R.S. Lazarus. 1988. Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 466–475.

Goodstein, L.D., and W.W. Burke. 1995. Creating successful organization change. In Managing organizational change, eds. W.W. Burke, 7–9. New York: American Management Association (AMACOM).

Greenwood, R., C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, and R. Suddaby. 2008. The Sage handbook of institutionalism, 1–47. SAGE publications.

Jackson, S.E., and R.S. Schuler. 1995. Understanding human resource management in the context of organizations and their environments. New York University: Department of Management.

Jex, S.M., P.D. Bliese, S. Buzzell, and J. Primeau. 2001. The impact of self-efficacy on stressor-strain relations: Coping style as an explanatory mechanism. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 401–409.

Kilduff, M. 1993. The reproduction of inertia in multinational corporations. In Organization theory and the multinational corporation, ed. S. Ghoshal, and D.E. Westney, 259–274. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Kilman, R.H. 1984. Beyond the quick fix. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lawson, E. 2003. The psychology of change management. McKinsey Quarterly 2: 1–8. Available at: www.mckinseyquarterly.com

Lazarus, R., and S. Folkman. 1985. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48: 150–170.

Lazarus, R.S., and S. Folkman. 1987. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality 1: 141–169.

Lazarus, R.S., and R. Launier. 1978. Stress-related transactions between person and environment. In Perspectives in interactional psychology, ed. L.A. Pervin, and M. Lewis, 287–327. New York: Plenum.

Lewin, K. 1945. Conduct, knowledge, and acceptance of new values. In Resolving social conflicts and field theory in social science, ed. K. Lewin, 48–55. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Meyer, J.W., and B. Rowan. 1977. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology 83: 440–463.

Martin, O. 2013. Change leadership: Developing a change-adept organization. Development and Learning in Organizations, An International Journal. 27(6).

Prochaska, J.O., W.F. Velicer, J.S. Rossi, M.G. Goldstein, B.H. Marcus, and W.L. Rakowski. 1994. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychology 13: 39–46.

Schein, E.H., and W. Bennis. 1965. Personal and organizational change via group methods. New York: Wiley.

Scott, W.R. 2008. Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Selznick, P. 1996. Institutionalism “old” and “new”. Administrative Science Quarterly 41: 270–277.

Simon, H.A. 1945. Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organization. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Smith, I. 2005. Achieving readiness for organizational change. Library Management 26 (6/7): 408–412.

Walinga, J. 2008. Toward a theory of change readiness. The roles of appraisal, focus, and perceived control. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 44 (3): 315–347.

Washington, M., and H. Hacker. 2005. Why change fails: Knowledge counts. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal 26: 400–411.

Weiner, J., H. Amick, and Y. Lee. 2008. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: A review of the literature in health services research and other fields’. Medical Care Research and Review 65: 379–436.

Weiner, J., A. Lewis, and A. Linnan. 2009. Using organization theory to understand the determinants of effective implementation of worksite health promotion programs. Health Education Research 24: 292–305.

Zucker, L.G. 1983. Organizations as institutions. Research in the sociology of organizations, 21–47.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Asfaw, E.W. (2017). Literature Review of Readiness for Change in Ethiopia: In Theory One Thing; In Reality Another. In: Achtenhagen, L., Brundin, E. (eds) Management Challenges in Different Types of African Firms. Frontiers in African Business Research. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4536-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4536-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-4535-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-4536-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)