Abstract

This chapter offers glimpses into the world of the pre-service teacher and identifies some of the vulnerabilities that might be encountered during this time. An important part of this period is the school-based professional experience, in which pre-service teachers observe and participate in authentic teaching and learning settings where they become acquainted with the requirements and practice of their future profession, learn about teachers’ work, implement university learning and gain experience in schools. These rich, dynamic periods are, surprisingly for many, imbued with multiple layers of learning and uncertainty. Along with the excitement of becoming a teacher, learners must grasp the obligations of the profession, form and maintain relationships with school-based practitioners and demonstrate effective pedagogical practices. Strategies are described that can help to strengthen a sense of self and competence and support the development of pre-service teacher identity as these teachers engage with localised social and cultural norms.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Teacher Education

- Teacher Education Program

- Active Engagement

- Professional Identity

- Professional Experience

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The following is from the practicum journal of a pre-service teacher I will call ‘Lou’:

As I set off for another day at the ‘coalface’ I wondered what surprises the teacher and the class had in store for me. My first few days had been a bit of a whirlwind as I tried to observe what was happening in the classroom, in the school, and then link these ideas to my learning at the university. It didn’t seem to matter how well prepared I was, each day seemed to be a bit of a ‘lucky dip’ of events and I was not sure that I would ever really be ready.

So far 4 weeks of my Professional Experience is complete, I am about halfway through my university course and I am proud to say that I am doing well in all aspects. At school my teacher has been great. We have had rich conversations and there has been an abundance of opportunity for planning and teaching. The pupils were energetic, enthusiastic if often surprising, and overall I felt welcome at the school.

But a nagging thought persists...

Am I really cut out for this profession? Will I relish the challenges and triumphs of the classroom, the staffroom and associated educational spaces? At what point will I feel like I have become a teacher? I know I am not there yet and wonder if there is a piece of the puzzle that I have not yet located.

Unfortunately for Lou, there is no infallible recipe for teacher success. Attempts to produce a mechanistic recipe for teaching have invariably been made by those who have never facilitated learning in a classroom, or simply fail to capture the complexity of teaching and the diversity of needs in today’s classrooms.

Today, the guidelines for the preparation of a teacher are defined around academic expectations and demonstrable pedagogical success within situated practices. Across Australia teachers are typically prepared for the profession via higher education courses, whether a 4-year undergraduate Bachelor of Education degree or an approved post graduate teaching qualification. Upon completion, graduates can register as a teacher and teach pupils from zero to 18 years of age, according to their nominated teaching stream or specialisation. Academic coursework in the university is supplemented by a requirement to undertake incremental and supported teaching roles as identified in the accredited course structure. These periods, known as professional experience or practicum, are integral to all teacher education programs and play an important part of becoming a teacher. Exciting, rich and dynamic, professional experience remains multifaceted and uncertain, as pre-service teacher learners form new professional identities and develop relationships with school-based practitioners.

This chapter seeks to inform, guide and support pre-service teachers in strengthening their sense of self and self-competence as they become a teacher. In particular, it addresses some key ideas that have been instrumental in forging constructive change in teacher education. The work of Donald Schön, Dan Lortie and Deborah Britzman, in particular, provide background and some strategies around harnessing inner strength and developing a subsequent professional identity in order to pursue worthwhile, autonomous and transformative outcomes during the teaching practicum.

Professional Experience

Professional experience is acknowledged as an essential requirement for initial teacher education, offering pedagogically sound, scaffolded approaches that mesh the principles and theories of education with a transparency of practice that embeds differentiation for a diversity of learning needs. In defining professional experience, Schön (1987, p. 37) suggests that it ‘approximates a practice world, students learn by doing, although their doing usually falls short of real-world work. They learn by undertaking projects that simulate and simplify practice; or they take on real-world projects under close supervision’

Traditionally known as ‘student teaching’, professional experience or practicum is the period of time that pre-service teachers spend observing and participating in authentic teaching and learning settings and, in this respect, it has changed little from Schön’s description. A primary purpose of these periods is to provide pre-service teachers with opportunities to become acquainted with the requirements and practice of their future profession, learn about teachers’ work, implement university learning and gain experience in schools.

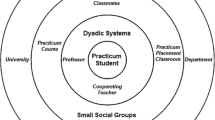

Undertaking professional experience triggers a connection between the worlds of the pre-service and the practicing teacher. During this time the pre-service teacher meets a triad of requirements: the immediacy of classroom practice, the needs of educational organisations, and the expectations of the classroom teacher. As Dan Lortie explained, during this ‘apprenticeship of observation’ period an emphasis is placed upon on a capacity and willingness to learn. The interplay of motivation, behaviours, attitudes and interpersonal communications remains contingent upon the lens with which normalcy is perceived. Paradoxically, as Britzman (2007) points out, pre-service teachers will innately bring prior experiences into in-school placements, combining important parts of their personal history and emerging teacher identity, yet these knowledges can often be unnoticed or disregarded by practising teachers, who may view the pre-service teacher as a blank slate.

Assessment of pre-service teachers’ professional experience has been variable, with students undertaking observations and scaffolded teaching, and with evaluations provided by academic and school-based staff. Across Australia, methods of evaluating pre-service teachers normally include assessment approaches that identify academic and practical progress. Largely modeled on the US designed Performance Assessment for Californian Teachers (PACT 2008) and Authentic Teacher Assessment (ATA) (Allard et al. 2014) these assessment approaches typically comprise a capstone portfolio that demonstrates evidence of a pre-service teacher’s learning and teaching ability, with explicit responses aligned to expected standards of practice. The current national standards (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, AITSL 2011) that have been developed for Australian teacher graduates, teachers and school leaders represent mutually agreed expectations for Australian educators and have been designed to promote excellence in schools.

Despite this uniformity of articulated standards and expectations, today’s teachers increasingly represent a rich diversity of age and backgrounds, cultures and life experiences that offers a wealth of learning opportunities for Australian classrooms. Valuing, embracing and integrating these accumulated histories and biographies with educational practices are a part of the overall challenge in readying the next generation of teachers. While many hold a view that a national and consistent approach to teacher quality will be of benefit for all learners across the nation (Santoro et al. 2012), others view the present prescribed teaching standards as narrowly instrumental, with inherent limitations that signify inflexibility and a failure to meet the complexities and uncertainties of the contemporary educator in the twenty-first century (Biesta 2015; Britzman 2007; Reid and O’Donoghue 2004). Whilst discourse about what constitutes best practice for education continues, there remains an acknowledged need for teacher succession, in which the renewal of educators in our accountable and competitive world is critical.

We are reminded again of Lou’s predicament. Questioning whether there is some marker of true readiness for the classroom and wondering at what point this will become apparent is a quandary that pre-service teachers regularly encounter. There is no question that teachers must be adept, flexible, and able to judge learning in terms of usefulness and applicability to life matters. However, in today’s competitive, accountable, and transnational world sits an irony where corresponding educational practices are equally as uncertain as those global developments that surround us. For example, schools are increasingly required to demonstrate (Bradley et al. 2008), to be publicly accountable for student learning outcomes with improved school performance exposed through national assessment examinations. As a consequence, the duties of the teacher are increasingly difficult and demanding as they take on greater responsibility, with repercussions on the demands placed on pre-service teachers.

An unwritten requirement for successful transformation to teacher is the development of a teacher lens that is attainable through observations and close, interactive working relationships with practising teachers. Yet this lens can be unsettled and disoriented by challenges that emanate from the pre-service teachers themselves. So too can the emotional experiences; the nature of feedback and the quality of relationships form a sphere of colliding forces, impacting upon the emerging pre-service teacher and their corresponding, professional identity. In pre-service teacher education, an integral teacher-student relationship is embodied within the professional experience. In the increasingly complex role of becoming a teacher, it is critically important that beginning teachers explore their own experiences, relationships and interactions in order to develop a growing sensitivity and attunement to the needs within the situated experience. Should relationships be sound, success can be a conclusive outcome with dialogue and ongoing support being mutually beneficial (Buckworth et al. 2015). In instances where relationships are symbiotic, reciprocal and collaborative, sound and seamless pedagogic practices can evolve, with options to mutually shape and align the outlooks and skills of the pre-service and practising teacher. Where relationships are power-based, emergent identities and relationships are particularly vulnerable and demand that pre-service teachers exercise discreet and informed judgments that comply yet engage with the localised social and cultural norms. Unlike Lou there may be many pre-service teachers who struggle to form sound relationships during placement. Recognising that relationships are not static, that personal interactions are subject to change and that proactive discussion can advance opportunities for improving collegial interactions are aspects of relationship-building that require encouragement.

The importance of instilling active awareness of the emergence of teacher identity cannot be understated, as this is pivotal in shaping outlooks and obligations. Becoming a teacher integrates the biography of the learner as they mesh not merely theories and practices, but also their values and beliefs played out as practices and framed within the context of their classrooms. Lortie (1975) explains this time as a fundamental period in which pre-service teachers begin to understand, not only what teachers do, but why they are who they are. Yet acceptance and a level of comfort in this new role are not automatic. In Greene (1973) Maxine Greene identified the teacher as a ‘stranger’, an outsider in a pre-existing community. As one yet to be qualified, the pre-service teacher is more of an outsider, an incomplete, unfinished project, in the process of becoming a teacher, unsure of their future, and uncertain of their place. Exploring these colliding biographies, Alsup (2005) describes ‘situated identities’ in which ‘borderland discourses’ emerge during initial teacher education as the pre-service and practising teacher become familiar with and accepted by each other.

Returning once more to Lou’s dilemma, we are reminded of a deep-seated human need for certainty. We remain wary of the unknown yet nostalgic around our past, as it is our past that confirms our approaches to today’s realities. One challenge for pre-service teachers according to Britzman (2003, p. 221) is the negotiating, constructing, and ‘consenting to their identity’ as they become teachers. In reality the pre-service teacher is entering a space where there are inherent expectations of learning to live with others and beginning to understand others, although Beauchamp and Thomas (2009) questions the notion of a requisite ‘acquiescence to an identity’ and suggests that this represents acceptance of non-negotiable institutional values, with little room for negotiation or mutuality. Beauchamp maintains that identity development builds on a fundamental requirement of internalised awareness of the ongoing shifts taking place in their experiential learning. Alongside these perceptions, new constructions of knowledge, often moulded by managerial discourses in school and universities and accountability requirements by regulators, may generate conscious and unconscious challenges for students (Hastings 2010), with factors that influence identity development, including emotions, resilience, efficacy and trust.

Perhaps Lou’s doubts are fueled by deep-seated reservations of self-worth. Studies of pre-service teacher silences and voice (Bloomfield 2010; Britzman 2003) highlight some of the hesitancies and emotions for students and identify feelings of isolation, inadequacy, resentment and vulnerability along with the fundamental need to feel accepted. As teachers interact and intersect with others, their sense of identity and agency can be a powerful and productive force, yet forming this teacher identity remains largely premised on relationships with others, and relies on outlooks of competency, self-esteem, and self-direction (Pearce and Morrison 2011). Traversing new territories and relationships during professional experience can result in unease that may be hard to identify.

Working in unfamiliar settings can pose challenges with unfamiliar social norms. For pre-service teachers this may be accompanied by a feeling of a loss of belonging and increasing uncertainties as they seek to integrate new learning into classroom practices. For some this is a time of discomfort and uncertainty, and compounded with other factors, it can generate conditions where the student, as an individual, can feel disempowered. Transitioning to this new perspective is not spontaneous and, while Lou has indicated a history of success, hesitancy towards the future continues to loom large. On the one hand, the teacher is the expert, demonstrating normative, unchallenged practices whilst offering opportunities for the pre-service teacher to contribute. On the other hand, the pre-service teacher is in the midst of constantly becoming and is not well positioned to question the nature or direction of the relationship.

These situations are evocative of an earlier era where didactic approaches to education practices were customary. Supplanting the apprenticeship style or craft approach of the earlier twentieth century have been new approaches to contemporary initial teacher education programs. Replacing the practices of acculturate and replicate that were grounded in copying, modelling and repetition is a focus on mutual, collaborative and reciprocal approaches. The changed practices additionally offer a capacity to overcome the theory–practice binary that has prevailed for decades in teacher education. While different to the copy-and-reproduce apprenticeship model, imbalances of power endure. Students with prior experiences, internalised values and understandings that are in conflict with host schools and teachers can place the successful completion of the practicum and the course in jeopardy. A conscious and unconscious expectation held by many teachers is that pre-service teachers will demonstrate teaching as an emulation of their own normative and uncontested practices, values and beliefs (Britzman 1986). These processes of transference involve an unconscious transfer of attitudes and feelings from one relationship into another and can generate difficulties in supervision where different theoretical and value-laden standpoints prevail. Evaluation of pre-service teacher performance may reflect a replay of their own teacher training and unintentionally perpetuate practices of the past, whereby beginning teachers are legitimately instilled into a homogeny of practice. Placement evaluations entrusted to site-based teachers whose perspectives are incongruent with those of the pre-service student teachers can result in difficulties as the placement progresses. For example, viewing classrooms through a behavioral lens will offer different perspectives to a constructivist lens, and the resultant divergent values and expectations bring the potential for anomalous relationships. In essence, an otherwise nuanced lens can lead to deficit development that can be shaped by conflicting beliefs around morality, power, justice, investment, privilege, and interest. As a successful teacher, a mentor may make assumptions that the pre-service teacher will follow what they share, model and demonstrate.

Professional experience connects the world of the pre-service teacher with reflective practices where meanings are constructed through personal and social experiences. Central to Schön’s (1983) concept of reflective practice is the ‘enabling’ that results as learners begin to theorise their own practice. In advocating this, Schön notes:

Perhaps we learn to reflect-in-action by learning first to recognise and apply standard rules, facts, and operations (characteristic of the academic curriculum); then to reason from general rules to problematic cases, in ways characteristic of the profession (characteristic of academic curriculum and the practicum); and only then to develop and test new forms of understanding and action where familiar categories and ways of thinking fail (characteristic of extended practicum and ongoing professional experience) (Schön 1983, p. 40).

Deliberate and active reflection foregrounds the development of teacher identity and, as Schön has described, grows from informed and certain knowledge that can then lead to new perspectives and actions. As pre-service teachers learn to change or ‘transform’ their frames of reference and begin to answer the question ‘Who am I as a teacher?’, new outlooks can inspire and stimulate future action. New views will embed pragmatic, ethical and moral qualities, each quality drawing on personal values about what is good, with clear connections between the receptiveness, reflexivity and reciprocity of individuals, as collaborative and productive networks ultimately contribute to the development of teacher identity.

Three underpinning qualities that pre-service teachers are advised to bring to their professional experience can be captured under the banners of receptiveness, reflexivity and reciprocity, where:

-

Receptiveness is demonstrable through situationally appropriate and contextually relevant readiness and adaptability, in particular a capacity for coping with change, unpredictability and uncertainty.

-

Reflexivity involves deliberate, regular and critical reflection of self in relation to others, that becomes evident in the degree to which collaborative actions become established, and

-

Reciprocity inherent within the sharing of information, goals and responsibilities is a positive outcome that serves to expedite the mutuality of roles.

Acceptance into classroom spaces, however, is not automatic for all pre-service teachers, nor do classrooms stop to accommodate new teachers. In this critical time the pre-service teacher must be proactive, responsive to, and become part of the form and feel of the learning environment. Being accepted eases the ambivalence that a pre-service teacher might bring to teaching and this in turn strengthens the quality of experiences and capabilities. Key considerations for pre-service teachers to take to their professional experience are grounded in interpersonal endeavor. Pre-service teachers can look to develop these foundational qualities by directing explicit focus on clarity of vision, establishment of practices, and active engagement.

Clarity of vision provides a basis for pre-service and mentor teachers to interweave their understanding of personal and learners’ needs with sound pedagogical approaches to further that learning. Rich conversations and collaborative planning can provide key opportunities for joint clarity of vision and the construction of frameworks for future pedagogic opportunities.

Pre-service teachers may need to be assertive to ensure adequate opportunities to contribute to this collegial discourse. Active endeavor towards this can be beneficial in establishment of clear direction that is aligned seamlessly into a framework of planning for the school.

Establishment of practices consists of those efforts required by pre-service teachers and their mentor teachers to establish the means by which they will work together and communicate with each other. In the classroom environment, social interactions are integral to seamless and productive operation. Interpersonal awareness, flexibility and reciprocity are required as pre-service teacher and teacher colleagues negotiate roles and intertwine formal communiqués (such as student assessments and meetings) with opportunistic meetings (such as playground or staffroom chats).

Active Engagement with the class and classroom practitioner involves actively positioning oneself to make sense of others’ expectations and one’s own capabilities. It reflects openness to alternative perspectives and skills and acknowledgement of the diversity of approaches in the classroom. Importantly, active engagement is about developing a positive attunement to others, demonstrating respect for difference and a readiness to interact beyond the superficial, at professional and personal levels. For some this will be a gradual process, whereas for others it may be rapid.

It is unlikely that Lou will ever be absolutely certain of the teaching profession as a lifelong destiny. The rapidly changing world has generated a cascading effect on educational practice that has seen the development of policy and practice trailing behind the advances of the twenty-first century. If Lou can meet the professional experience requirements of today and then demonstrate adaptability, clarity of vision and active engagement, then the teaching profession will have secured a quality teacher for the future.

The Reflective Dozen

To conclude this chapter a collection of 12 questions, the ‘Reflective Dozen’, is offered for pre-service teachers to consider when embarking upon professional experience. These questions provide a useful tool in determining and enhancing the development of collaborative practice, and communicating and working together.

Clarity of Vision

-

How do I determine shared understandings about goals and directions?

-

What is the nature and value of my contributions to these goals?

-

What mutually agreed outcomes are sought?

-

What organisational policies and procedures need to be addressed?

Establishment of Practices

-

How are learners’ goals, values and anxieties heard in discussions?

-

What features are key to these discussions?

-

What structured and opportunistic communications do I seek?

-

Where do valuable discussions occur?

Active Engagement

-

How willingly do I engage with my mentor teacher?

-

How do I demonstrate my willingness?

-

How is respect for others evident in my practice?

-

How clearly have I understood the current classroom practice?

References

AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership). (2011). National professional standards for teachers. http://www.aitsl.edu.au/. Accessed 20 Feb 2012.

Allard, A., Mayer, D., & Moss, J. (2014). Authentically assessing graduate teaching: Outside and beyond neo-liberal constructs. The Australian Educational Researcher, 41(4), 425–443.

Alsup, J. (2005). Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces. Urbana: NTCE and Routledge.

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175–189. doi:10.1080/03057640902902252.

Biesta, G. (2015). What is education for? On good education, teacher judgement, and educational professionalism. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 75–87. doi:10.1111/ejed.12109.

Bloomfield, D. (2010). Emotions and ‘getting by’: A pre-service teacher navigating professional experience. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 221–234. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2010.494005.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education: Final report. Canberra: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

Britzman, D. P. (1986). Cultural myths in the making of a teacher: Biography and social structure in teacher education. Harvard Educational Review, 56(4), 442–455.

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Albany: State University of New York.

Britzman, D. P. (2007). Teacher education as uneven development: Toward a psychology of uncertainty. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(1), 1–12. doi:10.1080/13603120600934079.

Buckworth, J., Kell, M., & Robinson, J. (2015). Supportive structures: International students and practicum in Darwin schools. The International Journal of Diversity in Education, 15(1), 1–10.

Greene, M. (1973). Teacher as stranger. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Hastings, W. (2010). Expectations of a pre-service teacher: Implications of encountering the unexpected. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 207–219. doi:10.1080/1359866x.2010.493299.

Lortie, D. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

PACT (Performance Assessment for California Teachers). (2008). http://www.pacttpa.org/_main/hub.php?pageName=Home. Accessed 18 June 2016.

Pearce, J., & Morrison, C. (2011). Teacher identity and early career resilience: Exploring the links. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(1), 48–59. doi:10.14221/ajte.2011v36n1.4.

Reid, A., & O’Donoghue, M. (2004). Revisiting enquiry-based teacher education in neo-liberal times. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(6), 559–570. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2004.06.002.

Santoro, N., Reid, J., Mayer, D., & Singh, M. (2012). Producing ‘quality’teachers: The role of teacher professional standards. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(1), 1–3.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Buckworth, J. (2017). Issues in the Teaching Practicum. In: Geng, G., Smith, P., Black, P. (eds) The Challenge of Teaching. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2571-6_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2571-6_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-2569-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-2571-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)