Abstract

Family is the microcosm of culture, and child mental health needs to be contextualized within the framework of the family and the culture, for overall comprehension and care. Family can have an etiological or a causative role, perpetuating or a maintenance role, and a therapeutic or an ameliorative role, in children’s mental disorders. Our environment and sociocultural canvas are changing rapidly and so are the experiences, causing strain and dysregulation of various neurobiological systems, with potential for psychological malfunctioning. The brain and nervous system constantly adapt and change according to the environment wherein the newer systems and mechanisms develop and others are replaced or modified, in favor of survival. A series of adaptations bring about the evolutionary change in the structure and functions of the brain. Most psychopathologies in children and adolescents develop in the backdrop of family and the sociocultural system, necessitating need for advancing cross-cultural research with a specific focus on family issues. Findings from the western studies from the high-income countries may not be directly applicable in the Indian context or for that matter in the other low- and middle-income countries. The onus is on the experts, to be aware and also sensitive to both the family issues as well as the cross-cultural perspectives in the child and adolescent mental health care. Many countries are multicultural, and cultures by itself are dynamic and constantly evolving. The following text is a prelude to this sensitization. The discussion attempts to focus more on the low- and middle-income countries (LAMIC) alongside research from the Western world.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Child mental health

- Family

- Culture

- Child Development

- Psychosocial

- Psychological development

- Child mental disorders

Introduction

Family is the key and a primary social institution that transforms the human newborn from a biological being into a “human” being. Family is the first social community in the life of an individual where he/she finds fulfillment of basic needs; gains competence in various linguistic and cognitive skills; learns social and emotional behavior and its regulation; and imbibes social values, customs, code of conduct and morality, acculturation, and humanism. Family is both simple and a complex social unit, where each member is a unique individual and also a member of a whole family group. Members of the family share lifelong relationships by birth, marriage, kinship, or adoption and are guided by a common way of life, common social, psychological, emotional, moral, ethical, and legal relationships. Family is not chosen; one is born in it. It also provides maximum informal contact and emotional gratification to its members. The function of a family is to nurture each member and promote development in the areas of physical, emotional, social, moral, and cognitive domains. A family is also a unit connected to the society wherein it has the cultural functions of primary socialization, social behavior, and social control and norms thus promoting individuality for its members within the broad context of sociocultural reality. The family has multiple functions i.e., marital function, parenting functions, educational functions, emotional functions, social control functions, economic functions, and intimate and reproductive functions.

Family is a universal social group found in some form or the other in all societies whether primitive or modern. With the rise of civilization, it became necessary to have a family name to know the ancestry and descent primarily for inheritance purposes. Family helps in the propagation of human species and the human race. It legitimizes the act of reproduction, regulates and controls sexual functions within a society, and provides an individual with an identity.

A human child needs care and protection for its survival for the longest time as compared to that necessary for any other animal species. For this reason, the relationship between the offspring and its father and mother is prolonged and expanded during which the effort is made to impart to the child the cumulative knowledge available at that time. Unlike animals, humans are not endowed with an instinct for adjustment to environment and lack reflexes sufficient for survival. The child has to learn from the family, culture, and accumulated knowledge, self-protection and self-preservation that have led to the launching of systematic efforts towards their education and training, to teach what nature has not taught.

A family is a unit where great emphasis is placed upon one’s dependency and reliance upon others. Family can be seen as a unity of interacting personalities, who cohere in an ongoing structure that is both sustained and altered through interaction (Burgess 1926). There is a sense of obligation among family members, reverence for the elderly, and responsibility to care for all members, especially children (Zayas 1992). Familism is a commitment to provide an emotional support system for family members, and it emphasizes the importance of the family, as opposed to the importance of the individual (Cuellar et al. 1995).

Family regulates the majority of child-environment interactions and helps to shape children’s adaptation. Family is the first and the foremost arena within which the child experiences and experiments with expressions and control of emotions and impulses; learns norms and morality; accepts and is exposed to graded responsibility for self and others in the filial group and the larger society; develops social bonds and relationships. Most of the young children’s cognitive, emotional, and social repertoire stems directly from the experience they have had within the framework of the family. Family plays a key part in the process of shaping and guide children’s development and thus, contributes to overall child mental health. However, the structure and composition of family vary across countries, regions, and time. Emerging social realities and dynamics have brought about major changes in the family’s definition, structure, and functions.

Culture

Culture constitutes learned meanings and shared information transmitted from one generation to the next. Culture consists of distinctive patterns of norms, ideas, values, conventions, behaviors, and symbolic representations about life that are commonly held by a collection of people, persist over time, guide and regulate daily living, and constitute valued competencies that are communicated to new members of the group. Each society prescribes certain characteristic “cultural scripts” in child-rearing. Variations in culture make for subtle as well as manifest, but always impressive and meaningful, differences in child-rearing patterns and mental health.

Much of culture is acquired unconsciously through interaction with others in the cultural group, and also consciously enforced by rules and norms especially within the family, peer group, and school system.

Concept of culture refers to and incorporates three aspects:

-

1.

Progressive human achievements or civilization: It describes the whole sum of achievements by a man to protect itself against nature and making the planet serviceable, and to accommodate mutual relations. It also involves the intellectual, scientific, and artistic achievements of man and the leading role it assigns to the higher mental activities and ideas assigned to human life.

-

2.

Level of individual refinement: It refers to the level of the individual’s refinement in terms of assimilated knowledge and experience, sophistication, a personality that has assimilated the cultural ideals, attention to needs of others, and a peaceful and gratifying ways of life. There was a view of culture as “high culture” meaning refinement, knowledge, and educated taste.

-

3.

Culture as values, symbols, ideals, meanings, and ways of living: It is manifested in rituals, customs, laws, literature, art, diet, costume, religion, preferences, child-rearing practices, entertainment, recreation, philosophical thought, and the government (Sadock and Sadock 2007). This is the most commonly ascribed and general usage of the term culture.

Culture is imbibed and internalized through the process of development, early in life, and gets hardwired in the brain. Brain and nervous system constantly adapt and change according to the environment wherein the newer systems and mechanisms develop and others are replaced or modified, in favor of survival. A series of adaptations bring about the evolutionary change in the structure and functions of the brain. To fit into the civilized society, children are conditioned from birth to learn the art of meeting external demands, assume the socially adjusted roles, and accept the constraints of reality, even at the cost of their inner strivings. This can cause stress and conflicts. If these conflicts remain unresolved or these patterns are not adequately internalized, it may lead to brewing/simmering discontent ready to erupt into disease or aggression. The process of development can proceed optimally if the environment in which children are raised in safe, nurturing, repetitive, predictable, and attuned to the child’s developmental level or state. Our environment has changed and is changing rapidly, and the experiences encountered are more chaotic, overwhelming, and often abusive. Most of the mental health problems signify dysregulated internal systems.

Family, Culture, and Development

Family is integral to the development of an integrated personality and internalization of societal norms and culture through a primary process of socialization. The family acts as a conduit or a vehicle for transmission of culture into the individual’s personality, thus, keeping the culture alive. Family provides an opportunity for the sexual gratification of spouses and lays down prescriptive and proscriptive rules for sexual relationships within the society. Social control and regulation of sexual function is extremely important for maintaining social order. Members of a family live by and transmit the social and cultural values and norms to its offspring; thereby, shaping their personality and stabilizing the social system.

The family itself is shaped and afforded meaning by “culture” (Bornstein and Lansford 2010). Human beings do not grow up, nor do the adults carry out parenting in isolation, but in fact, all this happens in the context of culture. Just as cultural variation dictates the language which the children eventually speak; cultural variation also exerts significant and differential influences over the mental, emotional, and social development of children. It is the culture that influences how the family cares for children, what it expects of children, and which behaviors are appreciated, emphasized and rewarded, or discouraged and punished. Every culture is characterized and distinguished from other cultures, by deep-rooted and widely acknowledged ideas about how one needs to feel, think, and act as a functioning member of the culture. These beliefs and behaviors shape how the family rears their offsprings. Culturally universal or specific systems are required to be in place, to ensure that each new generation acquires culturally appropriate and normative patterns of beliefs and behaviors.

The goals of development vary with culture and social norms. In India, for example, emphasis is placed on values such as dependence and dependability, high frustration tolerance, patience, acceptance of pain (physical and psychological), forgiveness, and equanimity. In Japan, passive love or dependence, obedience, politeness, acceptance, and harmony are valued more. In Chinese culture, children are taught to cultivate politeness, collectivism, filial love, and respect towards parents and authority. In the psychoanalytic theory, dependence is considered as the continuation of the early essentially sexual bonds with the parents throughout life, wherein, libido attaches itself to the satisfaction of the great vital needs and chooses as its first objects the people who have a share in that process. Dependence versus independence has been regarded as the nuclear conflict in personality development where dependence is considered as a negative trait with pejorative connotations in the West. In the Indian and other eastern cultures, personal independence is not a cherished value. Ideal value in Indian society is “dependability” and “inter-dependence” and not independence.

In India, unlike in the West, there is a strong belief in the doctrine of reincarnation and transmigration of the soul, and that the child is born with the innate psychic dispositions from the previous life. Parents traditionally would accept this and would have little urgency or pressure to mold the child into any contrary patterns. Therefore, in traditional families, child-rearing is more relaxed, indulgent, and flexible. Alan Roland (1982), while discussing the inner development of personality in urban India, wrote that Indian child-rearing and social relationships emphasize more symbiotic modes of development, on one hand, and inhibiting the process of separation-individuation, on the other. There are extraordinarily close ties between the child and the mother, and ego boundaries are less sharply delineated; identification is more with the “we” of the family, leading to the development of a “familial self” rather than an “individual self,” which is quite unlike the west. There is a strong identification with the all sacrificing mother, and there is considerable regard for the feelings of others and an equally strong expectation of reciprocity. This tends to inhibit the development of a highly individualized autonomous self, which Erikson has viewed as underdeveloped, immature, and incomplete personalities; whereas, Alan Roland (1982) considers it a “richness of individuality” exhibiting close emotional ties, strong identifications, and collectivist orientation.

The definition of normalcy and abnormality also has cultural overtones. Designating behaviors as maladaptive will need to be contextualized in the given culture and interpreted accordingly. What may be considered normal in one culture may be considered abnormal in another. For example, sleeping in parent’s bed throughout childhood is not considered abnormal in India whereas it would be considered abnormal in the West.

Culture has a major influence on identity formation, and culture gets incorporated into our identity. Epigenesis in neuroscience informs that environment and culture get wired into the developing brain, much like software, most of which is established by the end of childhood. It is well known that children growing up in different cultures will grow up being different, acquiring the characteristics of that particular culture in its core. Once someone has grown up in a particular culture, he/she cannot acquire a full understanding of other cultures since the brain has gone through the process of culturization (Pinker 2003). Once established, this identity is ingrained in the deepest layers of the psyche and is not fluid or changeable. Despite apparent differences among people within a culture, there remain considerable similarities that set them apart from other cultures.

Culture shapes the programming of the mind (Heine 2008) and also influences the way mental distress is handled ranging from idioms of expression to the meaning of symptoms (Weisz et al. 1997, 2006; Canino and Alegria 2008).

Indian culture has been majorly influenced by the Vedas and the Indus or the Hindu civilization. There are certain core features of Indian identity which have profound influence on child development and personality formation such as the supremacy of family over the individual; collectivist thinking as opposed to individualistic thinking; social hierarchy; pursuit of “Dharma” (moral duty/obligation); ideas of health and disease in accordance with the tenets of Ayurveda; deep faith in religion and spirituality; belief in the theory of “Karma” (or action); belief in theory of rebirth and continuity of life after death; and pursuit of “Moksha” (salvation). Average majority of people would follow and live by these beliefs which will guide their behaviors, responses, and coping in varying situations and circumstances of life.

The strong family system in India is a source of tremendous strength to its members, and this should be (a) strengthened further to act as a fertile ground for healthy personality development; (b) protected and supported as a sanctuary for containment and resolution of emotional problems and interpersonal conflicts; and (c) guarded against influences favouring its disintegration and erosion, which are a serious threat as a result of globalization and westernization. (Malhotra 1998)

Cultural Context of Psychopathology in Children

The interface of culture and psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents occurs at several levels. Culture determines the conceptualization of normalcy or abnormality; varied risk and protective factors; and nature and expression of psychopathology.

There is enough literature available to suggest that presentation, experience, classification, attribution, prevalence, and outcome of mental disorders varies between cultures (Kleinman 1995). Rates of behavior and conduct disorders are reported to be lower among children of Chinese origin than those of American (Chang et al. 1995).

Community-based epidemiological studies from the developed countries report rates of mental disorders among children and adolescents being higher (between 15% and 20%), whereas those from India are lower (about 6%) (Malhotra and Patra 2014). Also, there are relatively lower rates of depression, substance use disorders, and disruptive behavior disorders and greater prevalence of subsyndromal disorders and monosymptomatic conditions like enuresis, and habit disorders in the Indian population (Malhotra et al. 2002, 2009). Depression, somatization, PTSD, and ADHD are some of the conditions where social-cultural factors play a significant role in their causation, presentation, and treatment.

The utilization of child mental health services in UK and USA is much less among people of Asian origin as compared to those of natives (Sue and Mc Kinney 1975; Stern et al. 1990).

Keren and Tyano (2003) described how Israeli-Arab conflict impacted the psychopathology among children and adolescents in Israel. “The Israeli prototype of the father is very much influenced by the place the army has in daily life: potential hero, potential death and the legitimate use of power and killing, are all internalized by the young child who seas, every year, his father wear the army uniform and leave home for several weeks, and his older brother comes home on leave from the regular army” (Keren and Tyano 2003). The change from civil clothes to army uniforms symbolizes the switch from one ethical code to another. In the former, violence is forbidden; in the latter, it is legitimate. In this scenario, children fail to learn sublimated ways to express aggression as parents and teachers find direct aggression as the only way to solve conflicts. Play themes of children in preschool nurseries involve killing. The stress and tensions associated with the process of acculturation following immigration of Jews from Morocco to Israel has led to several types of psychopathologies: e.g., syndrome of regression, such as acute dissociative states, brief psychoses, psychosomatic psychopathology; borderline psychopathology and problems in identity formation; cognitive dysfunction; and delinquency, suicidal, and homicidal behaviors (Keren and Tyano 2003, p. 107).

Up to 80% of the world’s children and youth live in low- and middle-income countries (LAMIC), whereas most of the child psychiatry research is done and reported from the west, on 20% children and adolescents living in the West. The industrialized countries of the West have already set the direction for CAMH research, based on their own appreciation and understanding of the subject, and the LAMIC tend to follow the global or universal trends for the sake of remaining contemporary and publishable. There is a need to use culturally sensitive approaches, tools, and methodologies without which there is a serious risk of decontextualizing the meaning and interpretation of distress and disorder, getting erroneous data sets and enacting misplaced policies. While most developed countries of the West (example Europe, Canada, the USA, Great Britain, and Australia) share the values of individualism, secularism, and internal locus of control; the LAMIC (of Africa, South Asia, South America, and Middle East) follow external locus of control, strong family ties, deference to authority, and strong religious beliefs (Inglehart and Welzel 2011).

The pathway towards a culturally nuanced CAMH research in LAMIC will require a contextualized understanding of the concept of childhood in such regions relative to the high-income countries of the West (Atilola 2015). Similarly, service delivery needs to be culturally nuanced where the families have to be invariably involved in the treatment; culturally adapted psychotherapeutic approaches are utilized; and alternative/cultural remedies such as spiritual healing, faith healing, herbal and ayurvedic remedies, yoga, meditation, etc. are acknowledged, and scientifically studied and validated. It is amply clear that mental health as a construct is not independent of society, culture, or situation, and that the Western definitions and solutions cannot be applied routinely to people in the developing countries (Summerfield 2008).

Family Context and CAMH

Mental disorders can develop as a result of family pathology or faulty communication or impaired interpersonal relationships. Although the individual is affected, yet the whole family is sick because of inter or intrapsychic problems. The possible role of the family in relation to the psychiatric disorder/psychopathology has been described broadly as:

-

1.

The causative role of the family (etiological)

-

2.

Maintenance role of the family (perpetuating)

-

3.

Therapeutic role of the family

The traditional joint households remain the primary social force in the lives of most Indians. Loyalty to family is a deeply held ideal for almost everyone. However. in the late twentieth century, the joint family in India has undergone some changes. Now the joint families are more flexible and well-suited to modern life. Actual living arrangements vary with social status, region, and economic circumstances like in cities, where ties are crucial for obtaining financial assistance or scarce jobs. Even though the ideal joint family set up is rare, there are strong networks of kinship helping in economic assistance and other benefits. Relatives live very near each other with easy availability for “give and take” of kinship obligations. When relatives cannot live nearby, they maintain strong bonds of kinship and provide each other with emotional support, economic help, and other benefits.

Family members have an important role in fostering and the care of young children and children’s positive development (Garcia Coll 1990; McAdoo 1978; Egeland and Stroufe 1981). In joint families, parents are helped by extended family members in nurturing and caring for children including teaching them disciplinary practices. Therefore, parents might be using lesser of physical punishment methods as their responsibilities get shared. But the frequency and quality of nurturing behaviors by parents is also low as there are other caretakers for the child also. Hence, it is said that the strength of joint families is decided by the number of caregivers apart from parents rather than the total number of members. For example, the presence of grandmothers is considered beneficial for children, and not of the uncle, cousin, or family friend (Furstenberg et al. 1987). The presence of a grandmother in African American and Hispanic families is associated with a responsive and less punitive parenting style, irrespective of ethnic identification or sex. The use of physical and verbal punishment is less, while reasoning and nurturance are more in joint family set-up.

One of the other ways of family living is Machismo where there are rigid sex roles, sex discrimination; male members are dominant, aggressive, authoritarian; attitudes towards women is callous; and there is inhibiting nurturing tendency (Deyoung and Zigler 1994). In these families, if the father is authoritarian, he inflicts punishment upon children (Bird and Canino 1982) which is accepted and seen as a way of assuring children’s proper behavior.

It is important to emphasize that children are valued for their economic utility, cultural heritage, as a means of perpetuating family lines, as sources of emotional satisfaction, and pleasure to decrease child maltreatment (D’Antonio et al. 1993). Studies have shown that who live within proximity to their families report greater life satisfaction (Ellison 1990),

Many parenting strategies, developmental milestones, and family processes are similar across cultures also. An evolutionary basis can be explained by the presence of species-common genome, shared historical and economic forces, and biological heritage of psychological processes. For example, it is expected in all societies that parents must nurture and protect their children (Zayas 1992), and that they must help children in achieving similar developmental tasks. All parents are expected to take care of physical health, educational achievement, social adjustment, and the economic security of their children. Furthermore, the mechanisms through which parents influence their children are universal. For example, culturally constructed selves in children are acquired through conditioning and modelling in a family. Children develop internal working models of social relationships through interactions with their families and that these models shape children’s growth and development.

Culture-based expectations about developmental norms and milestones affect parents’ appraisals of their child’s development. Hopkins and Westra surveyed English, Jamaican, and Indian mothers living in the same city and found that Jamaican mothers expected their children to sit and to walk earlier, whereas Indian mothers expected their children to crawl later. In each case, children’s actual attainment of developmental milestones accorded with their mothers’ expectations (Hopkins and Westra 1989).

A child’s interaction with the parents has an evolutionary bias. The child behaves in ways that enhance proximity to their caregivers. These early attachments provide an “internal working model” of the self; these form the basis of development of autonomy, personal competency, of control over the environment, and of mastery in the child (Ainsworth et al. 1978). But parental over-control and rejection limit the development of autonomy. High negative feedback from early attachment figures, usually parents, and poorly productive family environment leads to negative perceptions of the self and environment. High punishing and rejecting behavior of a mother is associated with significant internalizing and externalizing problems in a child. (Barling et al. 1993). A child sees the environment as hostile and threatening. He sees the self as less competent than others. These insecure attachments form the basis for anxiety and other psychopathology in children, which might continue later in adulthood (Eastburg and Johnson 1990; Krohne and Hock 1991).

Retrospective studies show that clinically depressed subjects perceive their parents to be more rejecting and controlling than do nondepressed controls (Bifulco et al. 1987; Gaszner et al. 1988).

First model of a one-to-one relationship for a newborn mostly is the mothers. They are the primary caregivers. A secure attachment with mother protects from separation anxiety. On the other hand, fathers introduce children to the world, to society, to people other than family. As such, a secure father-child attachment helps in protecting against social fears. A feeling of security in the relationship helps in socializing with strangers.

Also, the quality of mother and father relationships impacts child growth. Mutual understanding and support between the parents ensure a higher quality of mother–child interaction and more engagement of fathers with their child. However, mothers are more controlling and aggravating to their children when they have poor support of their partner. (Brunelli et al. 1995). Conversely, fathers who were/felt not supported by their partner have been seen to withdraw from their child (Lamb 1980). Because of the lack of support to each other, a child has feelings of insecurity.

Marital turmoil is a predisposing factor to childhood disorders. Poor conflict resolution styles (e.g., anxiety and withdrawal) are modelled. There are inconsistent disciplinary actions that are associated with internalizing problems in children. In the presence of marital turmoil between parents, children may experience uncontrollability which leads to anxiety. Parental conflict leads to poor bonding with children and serves as a constant stressor to a child’s environment. The child develops a poor sense of security.

In a study by Kaslow et al. (1984), maternal control and rejection at age 5 was later associated with self-criticism in girls at age 12. Similarly, paternal control and rejection predicted self-criticism in boys at age 12. These results held true even when child temperament was statistically controlled as reported by mothers. Also, clinically anxious parents have clinically anxious children. This might be due to exposure to children, learned behaviors, modelling of a parent figure. There is an intergenerational transmission of anxiety disorders. If both parents have insecure attachment patterns in their childhood, they provide a less warm, less structured, and less conducive environment to their children, resulting in insecure attachment patterns in children also predisposing them to various maladaptive behavior patterns (Cohn et al. 1992; Emery 1982).

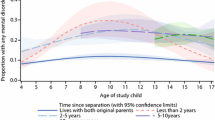

Also, it is important to note that children’s perspective of parental relationship quality is more important than changes in the family, like divorce, in determining children’s functioning (Cummings 1994). Mechanic and Hansell (1989) studied that adolescent mental health problems were significantly associated with reported conflict in the family. Moreover, problems increased with increasing conflict over time; whereas the same could not be predicted by recent or earlier divorce. Another longitudinal study conducted by Jekielek (1998) demonstrates that, although initial levels of anxiety in a child might be controlled, even then, both marital conflict and divorce predict anxiety even 6 years later. Moreover, though the effects of parental divorce fade with time, if children remain in high conflict environments the children’s anxiety remains maintained across time.

Literature has shown that poor family interactions disengaged family members, and negative conflict leads to the development of anxiety/depression, aggression, conduct and other behavioral problems in children. In the background of poor family adaptability, communication and lack of family encouragement, a sense of self-autonomy is not fully developed, which again forms the reason for fear of strangers, anxiety, and other problems in children (Peleg-Popko 2002).

Mental health problems are more common in children of poor families. Persistent poverty impacts children’s mental growth and is a reason for internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Persistent poverty, like in immigrants, is more of a risk factor than transient poverty, for various problems faced in childhood like a social disadvantage, familial discord, material deprivation, financial stress, and parental depression. The disciplinary practices adopted in such families are often reported as harsh. Poverty is a complex interaction between economic pressures, the pressure on lower-income groups, and the emotional and social problems of families. About one-third of poor children have families headed by single mothers. It was seen that in poverty-affected children, 55% are reared by single mothers compared with 10% in two-parent families. In the absence of one parent, usually fathers, the earning capacity of family is decreased, child support judgments tend to be poor (Wadsworth and Achenbach 2005).

Problems of mental illness and substance abuse in parents drive families towards poverty worsening the problems and deficits experienced by children. The clinical depression rates are two to four times higher than in general female population in female parent with low income (Larsson and Frisk 1999).

Child Rearing Practices and Mental Health

Child-rearing is the most important influential factor in pushing the developmental trajectory of children toward healthy or unhealthy patterns of emotions, behaviors, or cognition. There is literature to suggest that infant development is important in personality formation and psychopathology (Rutter 1997; Bowlby 1969). However, many social, emotional, and behavioral problems occur in the context of the suboptimal environment that are transient, temporary, or reactive. These are not disorders per se but may mimic psychopathology and can be regarded as forerunners of psychiatric disorders (Hong 2016). In recent years, a sharp increase in the rates of child abuse and neglect, ADHD, autistic spectrum disorder, violence, bullying, substance use, Internet addiction, juvenile crimes, and sexual violence may not represent a true increase in the incidence of these disorders. Rather it points towards the possibility of reactive, transient, developmental, emotional, and behavioral problems arising as a result of rapid social change and unrest.

Culture pervasively influences when and how family care for children, the extent to which parents permit children freedom to explore, how nurturing or restrictive parents are, which behaviors parents emphasize, and so forth. Japan and the United States maintain reasonably similar levels of modernity and living standards and both are highly child-centered societies, but the two differ in terms of childrearing with quite contrasting styles. Japanese mothers expect an early mastery of emotional maturity, self-control, and social courtesy in their children, whereas American mothers expect an early mastery of verbal competence and self-actualization in theirs. American mothers promote autonomy and organize social interactions with their children to foster physical and verbal assertiveness and independence. By contrast, Japanese mothers organize social interactions with children to consolidate and strengthen closeness and dependency within the dyad, and they tend to indulge young children.

On average, mothers spend between 65% and 80% more time than fathers do in direct one-to-one interaction with young children in Japan. Most fathers are either inept or uninterested in child caregiving. However, mothers and fathers tend to divide the labor of caregiving and engage children emphasizing different types of interactions, mothers providing direct care and fathers serving as playmates and support. Research involving both traditional and nontraditional (father as the primary caregiver) families show that parental gender exerts a greater influence than parental role or employment status. Western industrialized nations have witnessed an increase in the amount of time fathers spend with their children; in reality, however, most fathers are still primarily helpers. Notably, different cultures sometimes distribute the responsibilities of parenting in different ways. In most, the mother is the principal caregiver; in others, multiple caregiving may be the norm. Thus, in some cultures, children spend much or even most of their time with significant other caregivers, including siblings, nonparental relatives, or nonfamilial adults. Various modes of child caregiving, like nurturance, social interaction, and didactics, are distributed across diverse members of a group.

Lansford et al. (2005) studied samples from Italy, China, India, Kenya, Thailand, and the Philippines. Across all six cultures, he showed that higher the corporal punishment used by mothers, higher is the number of aggressive and anxious/depressed syndromes in children. Also, children who reported that parents used corporal punishment, rated themselves high on the aggressive behavior syndrome, regardless of their own mother’s report.

The Changing Family Systems

There is a pervasive and growing impact of urbanization, westernization, and globalization, all over the world, with rapid changes in the socio-political-economic systems, with huge implications for child development and mental health. Many of the Asian countries and oriental cultures are undergoing “modernization” including the adoption of capitalism, democracy, gender equality, human rights, individualism, sexual liberalism, and so on. These changes have many positives like the increased standard of living, opportunities for better education, health and employment, awareness of rights, and communication; however, there are many negatives associated. This transition has led to changes in the structure and functioning of the family units, alteration in child-rearing practices, redefining the goals of development, diminution of social support systems, and increasing levels of stress and trauma. How percolation of Western ideology and lifestyle in South Korea and other eastern cultures has negatively affected child mental health and caused a crisis of parenting and child-rearing is amply brought out by Hong (2016). The pursuit of materialism, competitiveness, social success, having become dominant values in Korea, have replaced the traditionally cherished higher values such as integrity of personality, harmony, good interpersonal relationships, control of emotions, family cohesion, respect for, and acceptance of authority and age. There is a consequent increase in rates of children’s emotional and conduct disorders, violence and sex-related crimes, drug abuse, divorce, and broken families (Hong 2016).

The sociocultural milieu of India is also changing at a tremendous pace in social, economic, political, religious, and occupational spheres, including familial changes in marital dyadic equations, the role of women and power distribution. A review of the national census data and the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data suggest that nuclear families are gradually becoming the predominant form of Indian family institution, at least in urban areas. The 1991 census, for the first-time reported household growth to be higher than the population growth, suggesting household fragmentation; a trend that gathered further momentum in the 2001 and the 2010 census. Other important trends include a decrease in the age of the house-head, reflecting a change in the power structure and an increase in households headed by females, suggesting a change in traditional gender roles.

Single-parent families, working couples, in the absence of a good alternative or support system, would risk optimal care of children. Grandparents or the hired domestic labor provided by young girls is the substitute care often. It is an irony that one class of children, especially the girls, have to take care of another class of children, compromising their own health. Then, there is the phenomenon of live-in relationships, wherein without the formal solemnization of marriage and the inbuilt commitment, the couple maintains all the other aspects of a conjugal unit. A child born out of such a relationship of parents is likely to have a relatively unsure future.

Effects of Societal and Familial Change on Mental Health

Social and cultural changes have altered entire lifestyles, interpersonal relationship patterns, power structures, and familial relationship arrangements in current times. These changes, which include a shift from joint/extended to nuclear family, along with problems of urbanization, changes of role, status and power with increased employment of women, migratory movements among the younger generation, and loss of the experience advantage of elderly members in the family, have increased the stress and pressure on such families, leading to an increased vulnerability to emotional problems and disorders. The families are frequently subject to these pressures.

Countries within the developing world are impatient and intend to achieve within a generation, what countries in the developed world took centuries. Hence, societal changes here are not step by step or gradual, but rapid, the process inevitably involving “temporal compression.” Additionally, the sequences of these societal changes are haphazard and often chaotic, producing a condition that is highly unsettling and stressful. For example, in a household where a woman is the chief breadwinner but has minimal standing in decision-making, the situation leads to role resentment and disorganized power structure in the family. Indeed, studies do show that the nuclear family structure is more prone to mental disorders than joint families. Fewer patients with mental illness from rural families have been reported to be hospitalized when compared to urban families because of the existing joint family structure, which provides additional support. Children from large families have been found to report significantly lower behavioral problems like eating and sleeping disorders, aggressiveness, dissocial behavior, and delinquency than those from nuclear families. Even the large-scale international collaborative studies conducted by WHO – the International Pilot Study on Schizophrenia, the Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders and the International Study of Schizophrenia – reported that persons with schizophrenia did better in India and other developing countries when compared to their Western counterparts largely due to the increased family support and integration they received in the developing world.

Although a bulk of Indian studies indicates that the traditional family is a better source for psychological support and is more resilient to stress, one should not, however, universalize. In reality, arrangements in large traditional families are frequently unjust in its distribution of income and allocation of resources to different members. Indian ethos of maintaining “family harmony” and absolute “obedience to elderly” is often used to suppress the younger members. The resentment, however, passive and silent it may be, simmers, and in the absence of harmonious resolution often manifests as psychiatric disorders. Somatoform and dissociative disorders, which show a definite increased prevalence in traditional Indian society compared to the West, may be viewed as manifestations of such unexpressed stress.

Resilience

All children exposed to adverse circumstances do not develop mental health problems. Majority are able to negotiate their lives safely and remain unscathed and they would be considered as resilient children. Resilience is a positive attribute that denotes the capacity of the individual to withstand stress and adversity and emerge stronger. Several individual factors (like genetic, hormonal, intellectual, and temperamental) and environmental factors (like a close relationship with caregivers, education, secure attachment and bonding, appropriate demands and expectations, optimal ecosystem, fulfillment of basic needs, safe and secure environment, etc.) contribute to resilience. Resilience is to be viewed as a product of an interaction between the individual and the environmental factors and can be fostered and promoted through developmental years of childhood by strengthening the individual strengths and promoting the positive environment and mitigating negativities. Several temperamental or personality traits enable children to overcome stress and develop a sense of competence and control in their lives. In a study on street children using case vignettes in Philippines, Banaag (2016) reported that traits in the individual that enhanced resilience in his sample included a sense of direction or mission, self-efficacy, social problem-solving skills and survival skills, adaptive distancing, having a hobby or a creative talent, a realistic view of the environment, self-monitoring skills and self-control, better intellectual capacity, easy temperament, disposition, capacity to recognize mistakes, sense of humor, leadership skills, sense of morality, and faith in religion or God. In the same study, several environmental protective factors were having family responsibilities, observing family rituals and traditions, positive family environment and bonding, positive relationship with at least one parent, families being morally supportive, and high expectations and supportive school climate. Mental health experts have not given much importance to resilience in production and mitigation of psychopathology; whereas, resilience as a developmental concept and attribute could, for its most meaningful interpretation, be better incorporated in all preventive and promotive mental health interventions, and in the definition of mental health.

Cyberage and Child Mental Health

Most children these days have access to computers, smartphones, iPad, and Internet and are spending hours on it for chatting, socializing, gaming, pornography, and sex. Internet addiction is a new behavioral addiction causing serious concern for parents and professionals. The more they spend time in this virtual world lacking in actual human contact, the more socially isolated they become, unable to fulfil their primary instinctual needs of attachment, aggression, and sexuality. This is impacting their development and contributes to increasing levels of social, emotional, and behavioral pathologies seen in the current times. Psychiatric disorders are a reflection of our current times and sociocultural milieu in which children are born and grow up.

Key Challenges for Mental Health Professionals/Services

The Challenges for the professionals working in the CAMH field is twofold:

-

In assessment (of family issues of CAMH in culture-specific context)

-

In management (of CAMH in cross-cultural perspective)

Children and families constitute an ever-increasing culturally diverse group in the clinical practice of CAMH services. Families and their children vary in their level of acculturation and developmentally may vary in their level of ethnic identification. Child-rearing patterns and parenting approaches are constantly in flux, as are gender roles. Clinicians are often challenged to treat such families and often find the cultural dissonance with their own native culture and theoretical frameworks as barriers for the appropriate assessment and treatment interventions. As the field of psychological interventions has developed, so have culturally sensitive and competent approaches in the field of mental health including CAMH. These approaches must be integrated into the multiplicity of other factors that define normality and psychopathology and be studied further in the context of their relevance and efficacy for special groups of children and families who suffer from specific psychiatric disorders. Cultural awareness and competence will help clinicians understand better the impact of values and patterns in the family, family organization, child-rearing practices, and the expression of symptoms in family systems in an index case.

Researchers have also recognized persistent ethnic differences in terms of utilization of services and unmet needs. The mental health needs of minority youth are not well served: They are treated less frequently, and when they are treated, the services they receive are less frequently adequate. Also, when ethnic minority youth do receive child and adolescent mental health care, the services that they receive may differ from those given to the White patients. The reasons for these discrepancies have been examined in numerous studies, and have included contextual variables (economics, availability, and accessibility of services), patient variables (differences in prevalence or manifestation of the disorder, cultural beliefs and attitudes, preferential use of alternative or informal services, health literacy, and adherence), and provider variables (referral bias and patient-provider communication). Awareness on the part of the practitioner of the cultural variables that influence help-seeking and ongoing utilization of mental health services may aid in the engagement, effective treatment, and retention of ethnic minority children and adolescents with depression. However, given the great heterogeneity that exists within any cultural grouping, clinicians will need to integrate information about cultural patterns with that obtained from the individual patient and family to inform optimal practices for each patient. Some aspects of culture that are likely to influence service utilization include increasing awareness; altering health beliefs, particularly regarding models of mental illness; and lowering the level of stigma toward mental health treatment.

Conclusion

Experiences in the family setting impact children’s vulnerability to various psychiatric disorders. Early-onset disorders become chronic or relapsing, predisposes to vocational and psychosocial impairments that have long-lasting deleterious effects. But even then, especially for young people, professional help-seeking rates remain low. Some factors like ethnicity, family history of psychopathology, and poverty cannot be changed. Hence, it is important to work on modifiable factors at the familial or individual level, e.g., on parenting patterns.

Preventive strategies include improving child relationship quality, positive parental involvement and skill encouragement, warmth, authoritative parenting, effective and consistent discipline, parental monitoring, good family communication, and problem-solving and reduced inter-parental conflict. Increased parental warmth decreases internalizing problems in young.

The changing family structure and parenting roles in the contemporary socioeconomic canvas is a stark reality. The child and adolescent mental health professionals need to take cognizance of the same. The Western studies from the high-income countries may not be directly applicable in the Indian context or for that matter in the other Low- and middle-income countries. This is because most of the LAMICs are multicultural and there is an imminent need for the culturally nuanced CAMH research (Atilola 2015). An understanding of the CAMH-associated risk and protective factors, which can be quite diverse and contextualized, along with the childhood psychopathology and the culturally nuanced intervention strategies, would be desirable. However, one must be aware of the fact that the cultural milieu in itself also continues to be dynamic (Draguns and Tanaka-matsumi 2003), and the society is in a constant state of flux and evolution.

References

Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S (1978) Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Atilola O (2015) Cross- cultural child and adolescent psychiatry research in developing countries. Glob Ment Health (Camb). Published online 2015 May 19; 2:e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2015.8

Banaag CG (2016) Street children: stories of adversity and resilience. In: Malhotra S, Santosh PJ (eds) Child and adolescent psychiatry: Asian perspectives. Springer India, New Dehli, pp 141–159

Barling J, Mac Ewen KE, Nolte ML (1993) Homemaker role experiences affect toddler behaviours via maternal well-being and parenting behaviour. J Abnorm Child Psychol 21:213–229

Bifulco AT, Brown GW, Harris TO (1987) Childhood loss of parent, lack of adequate parental care and adult depression: a replication. J Affect Disord 12:115–128

Bird HR, Canino G (1982) The Puerto Rican family: cultural factors and family intervention strategies. J Am Acad Psychoanal 10:257–268

Bornstein MH, Lansford JE (2010) Parenting. In: Bornstein MH (ed) The handbook of cross-cultural developmental science. Taylor & Francis, New York, pp 259–277

Bowlby J (1969) Attachment and loss, vol 1: attachment. Basic Books, New York

Brunelli SA, Wasserman GA, Rauh VA, Alvarado LE, Caraballo LR (1995) Mothers’ reports of paternal support: associations with maternal child-rearing attitudes. Merrill-Palmer Q 41:152–171

Burgess EW (1926) The family as a unity of interacting personalities. Family 7:3–9

Canino G, Alegria M (2008) Psychiatric diagnosis – is it universal or relative to culture? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:237–250

Chang L, Morrissey RF, Koplewicz HS (1995) Prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and their relation to adjustment among Chinese- American youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34(1):91–99

Cohn DA, Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Pearson J (1992) Mothers’ and fathers’ working models of childhood attachment relationships, parenting styles, and child behaviour. Dev Psychopathol 4:417–431

Cuellar I, Arnold B, Gonzalez G (1995) Cognitive referents of acculturation: assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. J Community Psychol 23:339–355

Cummings EM (1994) Marital conflict and children’s functioning. Soc Dev 3:16–36

D’Antonio IJ, Darwish AM, McLean M (1993) Child maltreatment: international perspectives. Matern Child Nurs J 21:39–52

Deyoung Y, Zigler EF (1994) Machismo in two cultures: relation to punitive child-rearing practices. Am J Orthop 64:386–395

Draguns JG, Tanaka- Matsumi J. (2003) Assessment of psychopathology across and within cultures: issues and findings. Behav Res Ther 41(7):755–776

Eastburg M, Johnson WB (1990) Shyness and perceptions of parental behaviour. Psychol Rep 66:915–921

Egeland B, Stroufe LA (1981) Attachment and early maltreatment. Child Dev 52:44–52

Ellison CG (1990) Family ties, friendships and subjective well-being among Black Americans. J Marriage Fam 52:298–310

Emery RE (1982) Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychol Bull 92:310–330

Furstenberg FF, Brooks-Gunn J, Morgan SP (1987) Adolescent mothers in later life. Cambridge University Press, New York

Garcia Coll CT (1990) Developmental outcome of minority infants: a process-oriented look into our beginnings. Child Dev 61:270–289

Gaszner P, Perris C, Eisemann M, Perris H (1988) The early family situation of Hungarian depressed patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 78(Suppl):111–l14

Heine SJ (2008) Cultural psychology. Norton, New York

Hong K-EM (2016) Rapid socio-cultural change, child rearing crisis, and children’s mental health. In: Malhotra S, Santosh PJ (eds) Child and adolescent psychiatry Asian perspectives. Springer India, New Delhi, pp 117–139

Hopkins B, Westra T (1989) Maternal expectations of their infants’ development: some cultural differences. Dev Med Child Neurol 31:384–390

Inglehart R, Welzel C (2011) The WVS cultural map of the world. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs/articles/folder_published/article_base_54

Jekielek S (1998) Parental conflict, marital disruption and children’s emotional well-being. Soc Forces 76:905–936

Kaslow NJ, Rehm LP, Siegel AW (1984) Social- cognitive and cognitive correlates of depression in children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 12:605–620

Keren M, Tyano S (2003) Socio- cultural processes in Isreali society: their impact on child and adolescent psychopathology. In: Young JG, Ferrari P, Malhotra S, Tyano S, Caffo E (eds) Brain, culture and development: tradition and innovation in child and adolescent mental health. MacMillan India, New Delhi, pp 105–110

Kleinman A (1995) Do psychiatric disorders differ in different cultures? The methodological questions. In: Goldberger NR, Veroff JB (eds) The culture and psychology reader. New York University Press, New York, pp 631–651

Krohne HW, Hock M (1991) Relationships between restrictive mother child interactions and anxiety of the child. Anxiety Res 4(2):109–124

Lamb ME (1980) The father’s role in the facilitation of infant mental health. Infant Ment Health J 1(3):140–149

Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA et al (2005) Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Dev 76(6):1234–1246

Larsson B, Frisk M (1999) Social competence and emotional/behaviour problems in 6–16 year-old Swedish school children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 8:24–33

Malhotra S (1998) Challenges in providing mental health services for children and adolescents in India. In: Young JG, Ferrari P (eds) Designing mental health services and systems for children and adolescents: a Shrewd investment. Brunner/Mazel, Philadelphia, pp 321–334

Malhotra S, Patra BN (2014) Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 8:22

Malhotra S, Kohli A, Arun P (2002) Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in school children in Chandigarh, India. Indian J Med Res 116:21–28

Malhotra S, Kohli A, Kapoor M, Pradhan B (2009) Incidence of childhood psychiatric disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry 51:101–107

McAdoo HP (1978) Factors related to stability in upwardly mobile black families. J Marriage Fam 40:761–776

Mechanic D, Hansell S (1989) Divorce, family conflict, and adolescents’ well-being. J Health Soc Behav 30(1):105–116

Peleg-Popko O (2002) Children’s test anxiety and family interaction patterns. J Anxiety Stress Coping 15:45–59

Pinker S (2003) The blank slate: the modern denial of human nature. Penguin Press Science, London

Roland A (1982) Toward a psychoanalytical psychology of heirarchial relationships in Hindu India. Ethos 10:232–253

Rutter M (1997) Clinical implications of attachment concepts; retrospect and prospect. In: Atkinson L, Zucker KJ (eds) Attachment and psychopathology. Guilford Press, New York, pp 17–46

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (2007) Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: behavioural sciences/clinical psychiatry, 10th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers, Baltimore

Stern G, Cottrell D, Holmes J (1990) Patterns of attendance of child psychiatry outpatients with special reference to Asian families. Special Issue: Cross-cultural psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry 156:384–387

Sue S, McKinney H (1975) Asian-Americans in the community mental health care system. Am J Orthopsychiatry 45:111–118

Summerfield D (2008) How scientifically valid is the knowledge base of global mental health? BMJ 336(7651):992–994

Wadsworth ME, Achenbach TM (2005) Explaining the link between low socioeconomic status and psychopathology: testing two mechanisms of the social causation hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 73:1146–1153

Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Eastman KL, Chaiyasit W, Suwanlert S (1997) Developmental psychopathology and culture: ten lessons from Thailand. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz JR (eds) Developmental psychopathology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 568–592

Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM (2006) Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 132(1):132–149

Zayas L (1992) Childrearing, social stress, and child abuse: clinical considerations with Hispanic families. J Soc Distress Homeless 1:291–309

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Section Editor information

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Malhotra, S., Kumar, D. (2020). Family Issues in Child Mental Health. In: Taylor, E., Verhulst, F., Wong, J., Yoshida, K. (eds) Mental Health and Illness of Children and Adolescents. Mental Health and Illness Worldwide. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2348-4_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2348-4_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-2346-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-2348-4

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences