Abstract

In contrast to studies of cognitive development in developmental psychology, researchers of a child-focused conversation analytic orientation seek to address the question—how do children acquire the relevant methodic social practices necessary for indicating during ongoing talk-in-interaction what it is to ‘know’. Employing a single-case study approach this paper considers the circumstances and contexts within which a young child demonstrates a development of understanding the word ‘know’ and/or the phrase ‘don’t know’ over time. The extracts discussed here have been selected from a larger corpus of conversation analytic based transcripts/recordings of a young female child between the ages of 1–3.5 years of age interacting with her parents, an older sibling and a family friend (of the author). The analysis traces out a developmental profile which moves from the correct use of the word ‘know’; through indications where ‘knowing and saying’ appear intertwined, and on to examples involving epistemic status and ‘knowing as performance’. Initially, the correct use of ‘know’ and ‘don’t know’ appears to be linked to practices of either avoidance or disagreement. Later, the significance of ‘knowing’ as related to being able to ‘say’ becomes evident, as well as instances where the child begins to recognize that ‘knowing’ can be related to being accountable (for what you know). The latter extracts also indicate the importance of ‘knowing ‘as performance. Overall, the analysis highlights the circumstances where a child begins to display an orientation towards epistemic discursive practices, highlighting the precarious and constantly shifting nature of the distribution of rights and obligations permeating talk-in-interaction.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Few studies in child language and developmental psycholinguistics have sought to establish when children begin to understand and use the word ‘know’. Typically the methods employed involved presenting or reading to young children sentences containing words and phrases involving ‘know’ and ascertain under what conditions they appear to understand the presuppositions and implications surrounding such use. Harris (1975) used a question-answer task format to investigate children’s use of the word ‘know’ and found that pre-school understanding was linked more to their general knowledge of the world (rather than the linguistic terms used) and it was not until between age four and seven years that they understood ‘know’ when used as a factive verb (i.e., when the use of a verb presupposes the truth of the statement by the speaker). Similarly, Abbeduto and Rosenberg (1985) report that children do not learn the presuppositional grounds for words such as ‘know’ and ‘forget’ until around aged 4, and Booth and Hall (1995) argue that a word such as ‘know’ is understood at different levels of abstracted meaning (perception through to metacognition), and learned with respect to a continuum of internal processing and information manipulation. In this cognitive-verb lexicon model of ‘know’, full acquisition is not firmly established until around seven years. Such lines of research correspond to the suggestion of Montgomery (1992) who asserts that only around the age of 6 do children begin to regard knowledge in a qualitatively different manner. They now understand knowledge as ‘subject to the constructive processes of the mind as opposed to being subject merely to what is, or is not, perceived’ (p. 425). In other words, rather than ‘knowing’ simply being an immediate perceptual process, children recognize that who is doing the perceiving, and the informational quality of what is being perceived, help inform the assessment made.

In contrast to studies of cognitive development in developmental psychology, researchers of a child-focused conversation analytic orientation seek to understand how children acquire the relevant methodic social practices necessary for indicating what it is to ‘know’ during ongoing talk-in-interaction Looking at make-believe in pre-school children’s play, Sidnell (2011) notes that children orient towards what he terms ‘territories of knowledge’—asymmetrical distributions of rights and responsibilities regarding knowing. Such orientations are highlighted in the details of the children’s make-believe play. The significance of undertaking a detailed and closely examined analysis of young children’s competencies and skills in context has been highlighted by Lerner et al. (2011) who makes the point that cognitive representational conceptions of underlying skills should conform to, ‘the actual requirements of the observable interaction order and participation in it—for example, the structurally afforded ability to recognize, project, and contingently employ unfolding structures of action in interaction with others.’ (p. 45). The argument is that whatever cognitive capacities are found to underwrite interaction order, the specification of the elements of this domain requires a close and systematic analysis of naturally occurring interaction addressed to the manifold contingencies of everyday life and the social-sequential structures that enable human interaction. Without understanding what it means to exhibit knowledge as a social practice in context, theories regarding cognitive representational process underpinning said actions remain abstract, disconnected and difficult to defend.

One helpful avenue for investigating how one acquires the skills needed to display, and recognize when actions presupposing ‘knowing’ are being produced in context, is the notion of epistemic status. Heritage (2012) proposed that during ongoing talk-in-interaction participants display an orientation to relative epistemic access and rights regarding appropriate displays of relevant knowledge (see also Canty Chap. 18 this volume). The suggestion is that relative access to a domain or territory of information is stratified between interactants such that they occupy different positions on an epistemic gradient (e.g., more knowledgeable [K + 1] or less knowledgeable [K − 1]), which may also vary in slope from shallow to deep. Heritage (2012) suggests:

Epistemic status is thus an inherently relative and relational concept concerning the relative access to some domain of two (or more) persons at some point in time. The epistemic status of each person, relative to others, will of course tend to vary from domain to domain, as well as over time, and can be altered from moment to moment as a result of specific interactional contributions. (p. 4)

This metaphor of a ‘see-saw-like’ movement permeating turn-design across speakers is said to inform what are called the response-mobilizing properties of sequential position (Stivers and Rossano 2010),—in other words how people respond to each other during conversation will depend on what each party understands the other person knows about the topic (or not). Heritage (2012) goes as far as to suggest that participants must at all times be cognizant of what they take to be the real-world distribution of knowledge as a ‘condition of correctly understanding how clausal utterances are to be interpreted as social actions’ (p. 26). We might note that within conversation analysis there are few studies that have documented the use of ‘don’t know’ or ‘I don’t know’ in adult conversation. Pomerantz (1984a, b), for example, when examining procedures related to displaying ‘how one knows’ documents instances of ‘I don’t know’ noting that people use such forms often in circumstances where they seek to express ambivalence. Not being fully committed to a particular epistemic position is also highlighted in the work of Weatherall (2011) who suggests that ‘I don’t knows’ can be categorized as either of two actions, first assessments and approximations. Sert (2013) notes the subtle forms of instructional related talk following instances of ‘I don’t know’ in learning contexts, and Stickle (2015) has recently examined the manner in which people with dementia often use ‘I don’t know’ not only to display epistemic stance but also to manage sequences of talk, for example when seeking to disagree with co-participants.

Turning to the question of how children might gradually acquire the intended understanding of utterances during talk-in-interaction, one or two studies have recently considered when and under what circumstances children begin to display an orientation to epistemic rights—who can say what, and when and with whom—and the extent to which such displays index their recognition or awareness of reflexive accountability, i.e., that other’s may take you to task for what you are saying and whether or not you have grounds for making the assertions you do (see Kidwell 2011; Lerner and Zimmerman 2003). Of particular interest is whether adult-child sequences of talk-in-interaction are by definition situations of recipient-tilted epistemic asymmetry (as Stivers and Rossano 2010, p. 23 express it). There may always be background assumptions and presuppositions about who is more (or less) knowledgeable permeating adult-child interaction.

We should be mindful, however, that being an ‘adult’ or ‘child’ does not automatically attribute epistemic status (e.g., that parents know more). Butler and Wilkinson (2013, p. 49) argue that children’s “(limited) rights to speak, engage, or launch action” constitutes a local, “interactionally situated” phenomenon. Such phenomena, as Keel (2015) notes cannot therefore be examined or explained with reference to a simplistic notion of participants’ orientation to a child’s young age, and thus to their not-yet-fully-competent way of speaking, engaging, or launching actions. In a recent summary of the relevant child-CA literature on assessment sequences in adult-child talk, Keel (2015) maintains that rather than reflecting participants’ orientation to distinct (epistemic) rights to assess and/or to an asymmetrical relationship between children and adults,

the way in which parents and children organize assessment sequences and, more specifically, the way they treat the parents’ weak agreements, signals the existence of issues that are more complex (p. 135)

Notwithstanding the challenges, limitations and benefits of what can be gleaned from a single-case study, the aim of this chapter is to consider something of the context within which a young child learns what is involved in recognizing and using explicitly the word ‘know’ and/or the phrase ‘don’t know’. The goal is to understand and explicate something of the circumstance when one child begins to use such expressions spontaneously in everyday talk-in-interaction during the early years.

The Data Corpus and Associated Video Recordings

The extracts discussed in this chapter come from a data corpus that consists of a series of video-recordings (31) of my daughter Ella, filmed during meal-times as she was interacting with family and occasionally, family friends. The participants described in the extracts are her father, mother, a family friend and the baby daughter of that friend. To facilitate the ease of collecting video footage in early recordings the target-child, Ella, was positioned in a high-chair and then subsequently sitting at the dinner table. The recordings began when Ella was 1 year old continuing until she was 3 years 7 months (at least once each month). The length of the recordings range from 10–45 min (average 35) with the total recording amounting to around 11 h. Transcriptions of all the recordings using conversation analytic conventions were produced (see introduction in this volume)alongside transcription notations relevant for child language analysis (MacWhinney 2007). The transcripts and digitised video-files are linked together using the software facilities of the CLAN suite of programs. The resulting data corpus can be viewed at http://childes.psy.cmu.edu/browser/index.php?url=Eng-UK/Forrester/. The specific location (identified by line numbers for the .cha files) are specified for each extract so that interested readers can view the recording clips for the extracts discussed.

With regards to the limits and challenges germane to methodology in developmental psychology and child language research, the single case study has a long and sometimes controversial tradition (see Wallace et al. (1994) for a summary, and Flyvbjerg (2006) on why the case study methodology is often misunderstood). The case-study approach that was adopted in the original study (see Forrester 2015) is best described as an exemplary case, that is one which provides an account of an instance held to be ‘representative’, ‘typical’ or ‘paradigmatic’ of some given category or situations. Such case studies are well-suited to exposition and instruction. We might note that the exemplary case study is distinguished from the symptomatic case and the particular case. The symptomatic case is regarded as epiphenomenal, as being generated from some underlying process. The particular case involves the study of some social event or phenomenon with the aims of explaining the case by orienting towards it as possessing a substantial identity (see Reason 1985). The conventions for an exemplary case study informed the selection of the examples.

Research Participation and Ethics

Care was taken with the video-recordings to ensure issues of participation were dealt with in line with the British Psychological Society’s Code of Conduct, Ethical Principles and Guidelines (British Psychological Society 2014).Footnote 1 Notwithstanding the importance of conducting the research in line with standard guidelines for this kind of research (e.g., consent from the child’s mother and sister and family friend were all obtained) it remains the case, at the very least, that children whose parents have granted their participation may be able at a later date, to challenge that consent, and in this case, for example, contest the procedures said to ensure that the data corpus is used solely for research purposes. As Ella was not in position to grant permission or not, this remains the case for the life of this project. I would like to acknowledge Ella Sbaraini who at the time of writing is happy for these recordings to be used for analysis and exposition.

Analysis

In order to highlight something of the developmental trajectory surrounding the changing use of the word know, the following extracts trace out a profile which moves initially from correct form use; through indications where ‘knowing and saying’ appear intertwined, and on to examples involving epistemic status and ‘knowing as performance’. Extract 1 serves as a good example where Ella begins to use the correct form for not knowing, around aged 2.

Extract 1:

Immediately prior to the sequence in this extract Ella and her father are having some disagreement over her request for an alternative kind of milk to the one in her bowl. By way of explanation and to avoid the possibility of conflict (which appeared possible as they had previously disagreed over her putting on a bib) the father suggests that he will give her some additional milk (more).

Child Age: 2;2 [112wks]: time in recording 10.32 (lines 360–384 in original file).

Having agreed to have some more milk (line 5), Ella produces an utterance which can be glossed as ‘that’s the milk the cow brought’ [us]. I seem to align to this suggestion indicated in the slight overlap of turns and repetition of the word ‘cow’. We then find (across lines 9–13) Ella producing a suggestion referring to the cow that appears to mean ‘him (the cow) didn’t know that there is more than one kind of milk’ or ‘what different milk does/can do’ (she may be assisting in glossing over the earlier disagreement with the suggestion that the cow who has ‘brought’ this milk, didn’t realize another different kind of milk was required (by Ella)). She makes this questioning statement with particular interest or attention, given that after she finishes speaking she awaits my reply, holding her spoon in mid-air until he responds (line 11). I do not appear to have heard the pronoun ‘him’ at line 9, and instead produce a clarification request marking Ella as the person who doesn’t know about ‘different’ milk. This she agrees with and the remainder of the conversation seems to indicate a continuing misunderstanding or misrecognition regarding her initial use of the word ‘know’ at line 9.

What is evident is that by age 2 years this child can use the correct form (as negation) and the reference she makes relates to the immediately preceding topic—the different milk she had asked for. One can suggest that her utterance appears to function as a kind of explanation about why she has to drink the milk that is available (even if her addressee probably doesn’t understand this—indicated in his downgrading response at line 18, and move to change the topic at line 20). At the very least we have an early example where the ascription of ‘not knowing something’ is assigned to somebody, and how this is responded to is of considered interest to the child. With adult data, Sert (2013) notes that ‘I don’t know’ appears to be associated with preference organization and often precedes something less than an agreement in everyday conversation. When used, people might be more attentive to how it is responded to by others.

In a second example 4 months later (extract 2 below) we find Ella being asked to recount an event from the immediately preceding day when a dog in the local park pushed her over. On being asked if she had told her mother about this, (line 3–5), it is interesting that Ella’s mother is already orienting to the event as being of interest. The manner in which her mother produces her ‘mmhmm’ utterance at line 6 is produced in the style of ‘oh, really, that’s interesting’ (similar to assessment sequences described by Keel 2015). I then ask Ella directly what the dog’s name was, and at that point it is quite noticeable that she stops eating, looks past me (and possibly in the direction of her mother), waits for at least 3–4 s without moving, and then replies ‘don’t know’.

Extract 2:

Context: Ella and her father are sitting at the kitchen table and Ella's mother is positioned out of camera sight. Just before the recording Ella has suggested she would like to leave the table but is instead being encouraged to stay and eat.

Child Age: 2;6 [133 wks] time in recording 08.32 (lines 440–457 in original file).

There is of course no way of ascertaining whether Ella is having trouble remembering the event or the dog’s name. What is marked is that when I make an assertion about the dog’s name, she replies no—not just once, but twice (at line 18) and during the second disagreement shakes her head in response to what I’m suggesting. What it is ‘not to know’ in this instance is unclear, and it is interesting that Ella indicates her own lack of knowledge—not remembering the name (line 10) and that she makes some effort to indicate that whatever it was, it was not the name that I have proffered. This may be an early precursor to the observation that Weatherall (2011) reports with adult data, where ‘I don’t know’ serves as forward-looking marker that indicates the speaker is not fully committed to what might follow but is nevertheless interested in what might follow. Sacks (1992) also makes the point that names and naming can do subtle work during talk-in-interaction, in that they are often not simply a convention but function as disguised descriptions where naming is often work that ‘does things’ (p. 414). A little further on during the same recording we find a clearer indication of what ‘not knowing’ means to Ella at this age.

Immediately prior to the beginning of the sequence Ella is eating in an inappropriate manner and I try and stop her and tell her not be ‘silly’. The way in which I do this elicits a comment from Silvia (Ella’s mother) that I seem a bit grumpy and out of sorts. During the earlier disagreement Ella and I produce a prolonged look at each other alongside other indications of ‘trouble in the talk’ (for example, I look at the camera in a noticeable fashion—line 9). At line 12 Ella’s mother, having commented that I seem ‘snatchy’ in front of the camera (annoyed), producing a laugh from me about her observation, then begins to comment about what Ella was doing in the immediately preceding ‘conflict’ sequence. As Silvia is making this comment (line 15) Ella is looking down at her lap, and produces an utterance asserting that she ‘doesn’t know’ something (line 16), which she then immediately repeats and repairs as she turns towards me (at line 18).

Extract 3:

Context: Two minutes after extract 2 above. Just before the beginning of the extract the father has attempted to stop Ella from eating her food in a way deemed inappropriate.

Child Age: 2;6 [133wks]: time in recording 11.09 (lines 580–613 in original file).

At this point (line 20) I repeat what she is saying however altering the last word to ‘dad’ but at this point without turning towards her or looking at her. Ella then (across lines 22–25), and having once again rolled her food in her hands and put it in her mouth, produces an utterance alongside what can best be described as a performance of ‘silly talk’. It is noteworthy that she is now repeating the earlier behavior deemed inappropriate (eating with her fingers) and there is a particularly noticeable emphasis on the word ‘know’ at line 22, and as she finishes her turn-at-talk (line 27), produces noticeable laughter. There are grounds for suggesting that Ella is successfully displacing the earlier trouble (through the production of ‘amusement’) and managing to continue to eat in the way she wanted to. What is interesting here is that it was her emphatic statements that she ‘didn’t know’ (line 18) which initially gained her father’s attention.

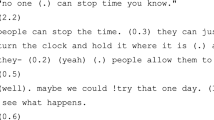

By line 29, having made some attempt at repeating what she has just said, I ask her what she means, and then suggest that she is trying to produce ‘nonsense’ as it is fun to ‘talk rubbish’. One interpretation of what is emerging here is that following our initial conflict, Ella observed my commenting on my disbelief or surprise (to Silvia) about the fact that she is not being normal, and being silly, and seeks to in part, resolve the trouble in the talk by then ‘acting silly’. The way to do this it seems is to talk in such a way that you ‘don’t really know what you are talking about’—and do so because it is fun (notice she produces an agreement to my suggestion that she likes talking rubbish—line 37). Whatever else has transpired, Ella has managed to continue eating in a way that was marked as inappropriate, and also resolved the apparent conflict between us by pretending ‘not to know’ what she is talking about because ‘she is silly’. What is significant here is that positioning yourself as somebody who ‘doesn’t’ or might not ‘know’ can serve as a helpful strategy when in a challenging situation (an observation described by O’Reilly et al. (2015) with older children). And ‘not knowing’ in this instance for Ella appears to be a reflexively accountable practice exhibited through making utterances that are demonstrably unintelligible.

Moving to another example recorded 2 months later, in extract 4 we find an instance where the use of the phrase ‘don’t know’ becomes part of an epistemic discourse presupposing uncertainty. While I’m arranging the camera and moving objects around the kitchen table, at line 11 I ask Ella where one of her toys has come from (and in this context meaning who put him there on the kitchen table just prior to eating).

Extract 4:

Context: The sequence below occurs as the father is moving the video-camera from one part of the kitchen to another.

Child Age: 2; 8 [140wks]: time in recording 13.17 (lines 544–664 in original file).

Examining the recording indicates that immediately after I ask this question I move to changing the viewing angle of the camera and as I’m doing so, Ella asks ‘where?’ (at line 13). There is then a noticeable gap immediately following her utterance (line 14) and in pursuit of a response she states that she doesn’t know—with a marked stretching of the word ‘know’. Why I should then reply ‘I’m not sure either’ seems a somewhat ambiguous response on my part, presupposing as it does my shared recognition of ‘not knowing’ where the toy has come from—even though I had originally asked her in a manner which indicated that Ella would be somebody who should know. This is an interesting example where the child is located in in a k+ epistemic position (to use Heritage’s 2012 terminology) and replies by positioning herself in a k- position, doing so through displaying uncertainty with the word ‘know’. Curiously, I then align myself with her by then positioning myself as somebody who also doesn’t know (k−). It seems quite possible that as I was moving the camera I was simply saying the first thing that came into my head, which she then simply repeats (at line 19). This extracts serves as a typical everyday instance where a child is being exposed to the immediately relevant sequential associations and presuppositions surrounding ‘knowing’—certainty, truth statements and hedges. There are grounds for saying that Ella is displaying those social practices that help ensure that you can abdicate responsibility for some state of affairs when required.

What it is to ‘know’ and what it is to ‘say’ become intertwined or interdependently related to the design of utterances around this age, as evident in Extract 5 below. Here there is an explicit orientation to knowing names (in this case of animals on playing cards) and what is presupposed by knowing how to ‘say the names’. The extract begins around line 2 where I ask Ella if her toy animal knows the names of various cards she is playing with on the kitchen table.

Extract 5:

Context: Ella is playing at the kitchen table with a set of large cards in front of her. The father is preparing food and talking to Ella as he doing so from another part of the kitchen.

Child Age: 3;3 [169 wks]: time in recording 3.38 (lines 157–177 in original file).

Ella appears to treat my utterance at line 2 not as a question but as an affirmative statement. Her disagreement is quite marked and in response I immediately provide a reason why it might be that her toy doesn’t know the names. Ella then goes on (across lines 7–15) to outline her toy’s limitations, specifying what these are—with a noticeable third-turn repair where I seem to mis-hear her (line 11). Here it seems clear that for Ella not knowing something presupposes not saying something. Schegloff (1972) makes the point that to ‘know a name’ and using names in context presupposes recognizability, that is, that the speaker or hearer can perform operations relevant to the naming such as categorizing and bringing relevant knowledge to bear on the naming practice—in this instance something that Ella indicates a soft toy does not have the competence for.

An association of this kind is also identifiable in Extract 6 where knowing a word, understanding its meaning, and being able to provide an account for why it has that meaning, becomes apparent. In this instance, recorded approximately 2 months later than the previous one, Ella and I have been discussing her use of a word ‘gonga’. This is a word she has used in the past and one that she has often seems to employ when referring to something that she doesn’t like or doesn’t wish to discuss (see Forrester 2015, p. 143).

Extract 6:

Context: This extract begins at a moment during the interaction where Ella’s father has been trying to encourage her to leave the table briefly and go to the toilet. Ella is somewhat reticent todo so.

Child Age: 3;5 [179 wks]: time in recording 06.10 (lines 291–337 in original file).

Prior to the beginning of the extract I have noticed that Ella might need to leave her meal and go to the toilet, and she has resisted my suggestion that she should. As part of that resistance, and in reply to my suggestion she simply say’s ‘gonga’ (line 8). Around line 20, I point out to her that her talk is somehow unreasonable as, when pressed, she won’t tell me what this word refers to. At line 26 I produce a reflexively oriented statement, pointing out what she does when I ask her what her word means. This elicits her response at line 14 that she doesn’t know along with laughter about this situation. I then continue to press her on the subject, first of all pointing out that she was the person who made up this word, and then suggesting or encouraging her to consider what it might mean.

There are a few interesting elements in the development of the requirement that if you use a word or phrase, then you should know what it means—even if it is a word that you might have only recently ‘made up’ (i.e., the selection should be sensitive to the ‘knowledge of the world seen by members… and to the topic or activity being done in the conversation at that point in its course’, Schegloff (1972, pp. 114–115). Notice the use of the conditional at line 26, and the production of a ‘reflexively accountable’ scenario (“If I say to you…), but then (line 28) instead of continuing with ‘what would you say’, instead I say ‘what did you say’—to which Ella replies ‘I don’t know’ at line 32 (not “I wouldn’t know what to say”). We then observe my explication of what might be implied when somebody makes up a word and then uses it, that is, you must know what it means. I then continue as if to suggest some possible candidate meanings, before again asking her what it ‘might’ mean. It is likely that it is through social discursive sequences of this nature that children begin to be exposed to the presuppostional criteria underpinning the use of words such as ‘know’ and ‘believe’.

Returning to the same context, the problematic nature of the interaction becomes more marked a little further on in the sequence (Extract 7) when the reasons for my concern with her going to the toilet made more explicit (lines 2–3 and lines 9–13).

Extract 7:

Context: The same as previous extract and a little further on in the recording (lines 408–443 in 179.cha in the CHILDS data corpus).

Child Age: 3;5 [179 wks]: time in recording 08.02 (lines 408–442 in original file).

The escalating production of disagreement between us leads to my asking her a direct question at line 19 to which she provides an appropriate answer. At line 23, and in a marked and noticeably louder voice, I then assert that what she has said is not true and furthermore that she knows it is not true (line 26), and that I also know that it is not true (line 29), and in both instances put a slight stress on the word ‘know’. Interestingly at this point (line 31) Ella then produces her assertion and claim that if fact it is true (that she does not need the toilet) doing so with a noticeable stress of ‘I’. This is the first instance in the data-set where her own positioning and epistemic status regarding a state-of-affairs is something that she can state unequivocally. Knowing in this case has nothing to do with saying or naming or performing ‘what it is to know’ but rather a claim intimately tied with embodiment. Notwithstanding the somewhat obvious parent-child asymmetry evident in the episode, her assertion about knowing is treated as something ‘not being the case’ and shortly afterwards in the sequence Ella asserts she wishes to leave the table in order to go to the toilet. For related work on how K+ and K+ epistemic positions co-produce conflict situations please see Rendle-Short Chap. 19 this volume, and Bateman (2015).

By the time Ella is around 3.6 years we find an instance where she displays an interest in positioning herself as somebody who is not an infant or a toddler but instead somebody who is old enough to be able to ‘click her fingers’. The extract begins at the end of a sequence of talk where a family friend (Louisa) is outlining something of the various life stages one goes through from birth to old age.

Extract 8:

Context: Ella is sitting at the kitchen table with a family friend’s younger daughter who is sitting in a high-chair.

Child Age: 3;6 [180 wks]: time in recording 04.13 (lines 214–246 in original file).

At the beginning of the extract Louisa is addressing Ella (and her father who positioned away from the table they are sitting at) and in response to Ella’s question at line 4 that one might become a baby again, asserts that when you are old you are ‘a bit like a baby’ because you don’t have any teeth anymore. As she moves the topic on and talks about having to wear false teeth, Elle interrupts and while pointing at a younger child in a nearby high-chair, asserts that first of all one is (you have) a toddler (line 13) with a particular emphasis on the word toddler. As she finishes talking she brings both her hands together in front of her and appears to make a shape in the space in front of her (and between her and her addressee).

After a short pause, during which Louisa appears to agree with this statement (line 16), Ella then raises her hands again and makes the shape needed to put your fingers together to make a ‘click’ sound. Ella at this point then produces a relatively long turn-at-talk (line 18) where first she asserts that she ‘knows how to click’ but when she does so it is somewhat disappointing as no clicking sound is produced (line 19). It is a sophisticated and detailed utterance with first of all an assertion, and then as she is producing the phrase ‘like this and it doesn’t’, she aligns her head with her arm as if in a ‘self-soothing’ way, and then at the end of the phrase ‘clicking noi:::se’, waves her hands in front of her.

This is the first instance in the data-corpus where Ella displays a reflexively accountable orientation to ‘knowing as performing’. She first of all makes an assertion (I know how to click), then provides an account of the difficulties surrounding what might be an adequate display of ‘knowing how to click’ as far as other people are concerned. Her addressee then seeks to establish what exactly she means by ‘clicking’ in this case (line 21), using her nails possibly rather than her fingers (a good example of the significance of action-semiosis through embodiment during talk-in-interaction—see Goodwin 2000). We then see (around line 30) a clarification request by Louisa who speaks while holding up and demonstrating the possible ‘nail-clicking’ that Ella might be doing (and not doing successfully). Ella does not answer, and at line 32 Louisa asks another question regarding clicking. Again Ella doesn’t answer and instead (around line 34) simply picks up a toy on the table. I treat Ella’s lack of a response to Louisa’s attempts at eliciting an answer as problematic in some way, as I produce a comment extending the suggestion made by Louisa to Ella. In this sequence there are grounds for arguing that Ella now recognizes that making assertions about knowing something (particularly where this ‘knowledge’ might be an index of your age or ability) carries with it criteria for being able to perform what that knowledge might be when asked.

Monitoring the ongoing talk of other people is evident in Ella’s talk by the 2 year (see Forrester and Reason 2006) and in the following extract where Ella’s use of ‘know’ is oriented to something she appears to remember and relevant to the ongoing conversation. At the beginning of this extract (Extract 9 below), Ella’s mother Silvia is asking me about a recent visit Ella and I had made to our local town. During the earlier part of the talk (lines 1–9) as I am explaining where I parked the car, Ella interjects into the conversation (she is painting while sitting at the table at this point) at line 11, where she extends the narrative development of my account to Silvia telling her that we went into the library to ‘get some new ones’ (in transpires that this refers to videos).

Extract 9:

Context: Ella’s mother and father are in the kitchen discussing their daily activities and Ella is sitting alongside the father doing some painting.

Child Age: 3;10 [198wks]: time in recording 04.15 (lines 227–255 in original file).

The anaphoric use of ‘news’d ones’ (line 11) is potentially problematic as there has been up to this point no discussion of videos, and Ella’s use does not take into account the fact that her mother is not to know what ‘ones’ refers to. Some orientation to the potential reference issue in the conversation seems to be evident in my design of my question to Ella at line 19 where I ask her specifically ‘what videos’ (not ‘what one’s) did we get?

At line 21 we then find once again the use of ‘know’ and her assertion that she remembers the videos we obtained (I know what they were = I remember what we collected). I agree to this assertion, but while doing so Silvia corrects Ella on what she has remembered. Knowing as remembering is, in this instance, an activity or social practice open to public scrutiny and accountability.

Concluding Comments

Over a relatively short period (1–2 years) it has been possible to trace out the manner in which Ella’s use of these words in the particular sequential positioning they occur, and gradually bringing into place an increased co-orientation to what is presupposed by such use, and especially the requirement to recognize the reflexively accountable particulars of such employment. Initially, the correct use of ‘know’ and ‘don’t know’ appears to be linked to practices of either avoidance (extract 1—moving away from the parent-child conflict over milk) or disagreement (extract 2—and the name of a dog). It was then possible to highlight something of a mutual co-orientation to the ‘knowing as saying’ and ‘not knowing’ associated somehow with Ella’s discursive self-positioning as ‘one who doesn’t know’ evident in talking nonsense (the performance of recognisibly ‘unrecognisble’ words and phrases (extract 3). Knowing, saying and the significance of being able to ‘name’ was also evident in extract 4 (her toy that couldn’t name cards).

The question of accountability surrounding the use of these phrases then becomes particularly evident by age 3.5 where Ella is required to provide something of an explanation for using a word that nobody else understands, based it seems on the requirement that if she has used this (unknown) word, then she must ‘know’ what the meaning is, and thus provide said meaning when asked (extract 10). That example appeared particularly striking as it would seem she was being provided with something of a tutorial on ‘what it is to produce a defensible account’ when necessary. Being accountable for making a claim or suggestion regarding your epistemic status is certainly evident in extract 7, where Ella has acquired the skills and resources to maintain her position regarding her unique claim to knowing.

In the latter two extracts we find good examples of ‘knowing as doing’, in the first case (extract 8) where Ella both makes an explicit claim to know how to do something yet at the same time displaying disappointment at not being able to successfully perform such knowledge (clicking her fingers). The concluding extract (extract 9) provides us with one of the more familiar instance where a parental first-assessment (mine) orienting to the status of Ella’s knowledge, is immediately superseded by an alternative assessment (her mother’s) indicating that her knowledge is misplaced. Such an example highlights the precarious and constantly shifting nature of the distribution of rights and obligations permeating talk-in-interaction. Hopefully through this brief examination of the fine-detail of the circumstances where one child begins to display an orientation towards epistemic discursive practices some additional understanding has been gained regarding the ‘territories of knowledge’—suffusing adult-child interaction during the early years.

By way of conclusion, in developmental psychology the earlier studies of children’s understanding of the words/phrases ‘know’ and ‘don’t know’ (Harris 1975; Booth and Hall 1995) have become supplanted by numerous and increasingly sophisticated experimental studies of ‘knowing’ and ‘common ground’ (Moll et al. 2007; Liebal et al. 2013). While revealing interesting aspects of, and insights into, early cognitive development, it remains the case that without understanding what it means to exhibit knowledge as a social practice in situ, then such theories remain somewhat constrained. To paraphrase Lerner et al. (2011) whatever cognitive capacities are found to underwrite the interaction order, the specification of the elements of talk-in-interaction that bear on any and all ascriptions of intentionality, requires a close and systematic analysis of naturally occurring interaction addressed to the contingencies of everyday life and the social-sequential structures that enable human interaction. An ethnomethodologically informed CA based single-case study can contribute to such forms of analysis as indicated above.

Notes

- 1.

See http://www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/code_of_human_research_ethics.pdf for the BPS guidelines.

References

Abbeduto, A., & Rosenberg, S. (1985). Children’s knowledge of the presupposioins of know and other cognitive verbs. Journal of Child Language, 12, 621–641.

Bateman, A. (2015). Conversation analysis and early childhood education: The co-production of knowledge and relationships. London: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. & Routledge.

Booth, J. R., & Hall, W. S. (1995). Development of the understanding of polysemous meanings of the mental-state verb know. Cognitive Development, 10, 529–549.

British Psychological Society (2014). Code of Human Research Ethics. Accessed 2 June 2016 at http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Public%20files/inf180_web.pdf

Butler, C., & Wilkinson, R. (2013). Mobilising recipiency: Child participation and ‘rights to speak’ in multi-party family interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 50, 37–51.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245.

Forrester, M. A. (2015). Early social interaction: A case comparison of developmental pragmatics and psychoanalytic theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forrester, M. A., & Reason, D. (2006). Competency and participation in acquiring a mastery of language: A reconsideration of the idea of membership. Sociological Review, 54(3), 446–466.

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489–1522.

Harris, R. J. (1975). Children’s comprehension of complex sentences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 19, 420–430.

Heritage, J. (2012). Epistems in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(1), 1–29.

Keel, S. (2015). Socialization: Parent-child interaction in everyday life (Directions in Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis ed.). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

Kidwell, M. (2011). Epistemics and embodiment in the interactions of very young children. In M. L. StiversTanya, & S. Jakob (Eds.), The morality of knowledge (pp. 257–282). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lerner, G. H., & Zimmerman, D. (2003). Action and the appearance of action in the conduct of very young children. In P. J. Glenn, C. D. LeBaron, & J. Mandelbaum (Eds.), Studies in language and social interaction (pp. 441–457). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lerner, G. H., Zimmerman, D., & Kidwell, M. (2011). Formal structures of practical tasks: A resource for action in the social life of very young children. In J. Streeck, C. Goodwin & C. D. LeBaron (Eds.), Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world (pp. 44–58).

Liebal, K., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2013). Young children’s understanding of cultural common ground. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 88–96.

MacWhinney, B. (2007). CHILDES—tools for analysing talk. electronic edition (http://childes.psy.cmu.edu/manuals/chat.pdf ed.). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Moll, H., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Fourteen-month-olds know what others experience only in joint engagement. Developmental Science, 10(6), 826–835.

Montgomery, D. E. (1992). Young children’s theory of knowing: The development of a folk epistemology. Developmental Review, 12, 410–430.

O’Reilly, M., Lester, J. N., & Muskett, T. (2015). Children’s claims to knowledge regarding their mental health experiences and practitioners’ negotiation of the problem. Patient Education and Counselling. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.005. (in press).

Pomerantz, A. (1984a). Giving a source or basis: The practice in conversation of telling ‘how I know’. Journal of Pragmatics, 8, 607–625.

Pomerantz, A. (1984b). Pursuing a response. In J. M. Atkinson, & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action. studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reason, D. (1985). Generalisations from the particular case study: Some foundational considerations. In M. Proctor & P. Abell (Eds.), Sequence analysis. London: Gower.

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation. In G Jefferson (Ed.), Introductions by E.A. Schegloff. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Schegloff, E. A. (1972). Notes on a conversational practice. In D. Sudnow (Ed.), Studies in social interaction (pp. 76–119). New York & London: The Free Press.

Sert, O. (2013). ‘Epistemic status check’ as an interactional phenomenon in instructed learning settings. Journal of Pragmatics, 45, 13–28.

Sidnell, J. (2011). The epistemics of make-believe. In L. Mondada, J. Steensig, & T. Stivers (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stickle, T. (2015). Epistemic stance markers and the function of I don’t know in the talk of persons with dementia and children with autism. (Unpublished PhD). Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin-Madison. (ProQuest Number: 3736880).

Stivers, T., & Rossano, F. (2010). Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1), 3–31.

Wallace, D. B., Franklin, M. B., & Keegan, R. T. (1994). The observing eye: A century of baby diaries. Human Development, 37, 1–29.

Weatherall, A. (2011). I don’t know as a prepositioned epistemic hedge. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 44(4), 317–337.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Forrester, M. (2017). Learning How to Use the Word ‘Know’: Examples from a Single-Case Study. In: Bateman, A., Church, A. (eds) Children’s Knowledge-in-Interaction. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1703-2_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1703-2_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-1701-8

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-1703-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)