Abstract

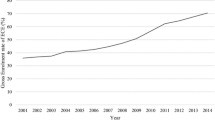

Since the first kindergarten was established in the late nineteenth century, the early childhood education (ECE) system in Taiwan has steadily evolved into one that aims to support all young children, regardless of their socioeconomic background. Reforms to the ECE system have rapidly increased since the millennium. In this chapter, we examine the ECE policies that have been proposed and implemented in Taiwan from the year 2000 to 2014. Specifically, we review these policies through the 3A2S framework: accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability, and social justice. Using the most recent data obtained from the Ministry of Education and other governmental agencies in Taiwan, we describe and analyse the trend of policy changes, examining whether these policy changes have yielded an ECE system that truly better serves the children of Taiwan. Our review indicates that the current governmental reforms have made Taiwanese ECE more accessible, affordable, and accountable to the families of young children, especially those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. With continued support at the federal and county level, these reforms should be sustainable in the years to come. In summary, the postmillennial governmental policies in Taiwan have vastly improved early childhood education for its future generations.

This research was completed with the help of Yu-wei Lin, Han-wen Liu, and Veronica Ka Wai Lai.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Gini Coefficient

- Early Childhood Education

- Kindergarten Teacher

- Disadvantaged Family

- Educational Expenditure

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Taiwan, the Republic of China, is a sovereign state in East Asia with the total land about 36,000 km 2 (Info Taiwan 2015). Approximately 23 million people live in Taiwan, speaking a wide variety of languages, including Mandarin Chinese (Putonghua), Taiwanese, Hakka, and indigenous languages. Taiwan is a democratic society, with its politics dominated by two main parties (American Institute in Taiwan 2012): the Kuomintang (KMT), the historically ruling party, and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), the party traditionally in opposition, although it gained political control from the year 2000 to 2008. Although early childhood education was created long before Taiwan became a democracy, its current form has been largely shaped by governmental policies and legal reformations, as well as by the efforts of nongovernmental stakeholders.

Early childhood education (ECE; please see Appendix for a full list of acronyms) has existed in Taiwan for over a century, growing rapidly from humble beginnings to a formalized system. The first recorded kindergarten was established during the Japanese occupation in the late nineteenth century. The private Taipei kindergarten was formed in 1901 to provide day care to young Japanese children residing in Taiwan and was later expanded to include local Taiwanese children as well (Lin and Yang 2007). During the 1950s, in response to the increasing number of women joining the workforce, the demand for early childhood care services also increased, leading the government to recognize childcare centres officially as “kindergartens” educating young children from ages 4 to 6 (Chen and Li in press; Lin and Ching 2012).

Through a series of government-initiated regulations since 1970, the ECE system in Taiwan has become more structured (see Chiu and Wu 2003; Lin 2002; Lin and Tsai 1996 for the specific governmental policies).

In 1987, the Taiwanese government published the standards of kindergarten curriculum (SKC) to regulate the quality of kindergartens (Lin and Tsai 1996). The following two decades saw a surge in efforts from the government and the private sector to improve ECE in Taiwan (Chiu and Wu 2003; Chen and Li in press). More public kindergartens were built, and schools received more resources from the government (Ho 2006). Starting in the year 2000, the government further streamlined the ECE system through:

-

(a)

The provision of free education through public ECE providers to 5-year-old children

-

(b)

The introduction of vouchers and additional support to children from economically disadvantaged families

-

(c)

The integration of kindergarten and day-care services

-

(d)

The establishment of government-supported, privately-operated kindergartens (i.e. allowing private kindergartens to be built on publically owned land)

-

(e)

The initiation of a teacher certification system to enforce consistency in instruction (Chen and Li in press; Li and Wang in press; Lin 2007)

From this brief overview of the development of the ECE system in Taiwan, it is clear that the importance of ECE has increasingly been acknowledged, especially from the Taiwanese government. Policies and laws concerning ECE continue to be created, debated, and revised; but the research on how these policies have shaped the ECE system in recent years has been relatively sparse. Therefore, we turn our attention to the postmillennial developments of Taiwanese ECE, with a focus on accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability, and social justice (henceforth known as the 3A2S framework; see Li and Wang in press; Li et al. 2010).

Given that the evolution of ECE in Taiwan has been largely driven by governmental initiatives, we focus on government documentation after the year 2000 as the primary source of information in this chapter. Specifically, we analyse the policies, laws, surveys, and other statistical information provided by the Taiwanese government using the 3A2S framework. The 3A2S framework allows us to assess the Taiwanese ECE policies in a more structured, rigorous manner, evaluating its appropriateness for all of the ECE stakeholders.

The 3A2S framework encompasses the following five dimensions: accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability, and social justice. Accessibility refers to whether every kindergarten-aged child can easily attend a kindergarten (e.g. the kindergarten should be in near vicinity to the child’s home). Affordability refers to whether kindergarten fees are within the financial means of the child’s family, including families of low socioeconomic status. Accountability refers to whether kindergartens are held responsible, typically by a governmental agency, for the quality of education offered. Sustainability refers to whether the quantity and quality of educational services provided can be maintained, also typically with the aid and supervision of the government. Finally, social justice refers to whether educational resources and opportunities are distributed fairly among different social strata and groups.

Examining the Taiwanese ECE policies in terms of their accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability, and social justice allows us to evaluate the effectiveness of these policies in improving the kindergarten early educational experiences of young children. Thus, using the 3A2S framework, we review the most recent government documents on ECE policies in Taiwan. Through this systematic inquiry, we intend to investigate whether the policies implemented after the millennium have yielded an ECE system that addresses the needs of children living in Taiwan.

Accessibility: Making ECE Available to All Qualified Children

A quality kindergarten education is beneficial only if it is readily accessible to kindergarten-aged children. Thus, the number of children who are eligible to attend school (i.e. the target population) and the number of kindergartens available are both critical to review the accessibility of ECE. We summarize (a) the number of kindergartens, both public and private, that were available throughout Taiwan from 2000 to 2014 and (b) the number of children these schools enrolled in Table 11.1.

The total number of public and private kindergartens has remained fairly consistent from 2000 to 2011, averaging at 3,326 schools per year during this period. However, there was a dramatic increase from 2011 to 2012, from 3,195 schools to 6,611 schools. This increase can be largely attributed to the passage of two laws. First, in 2011, a new law on ECE and care proclaimed that kindergartens could enrol children aged 2–6, thus extending ECE to children who formerly would only qualify for day care due to their younger age (Laws and Regulations Database of The Republic of China 2011). Second, in 2012, another law allowed day-care centres to apply to become kindergartens (Laws and Regulations Database of The Republic of China 2012a, b). As a result, day-care centres were integrated into the kindergarten system overseen by the Taiwan Ministry of Education (MOE), thus increasing the number of schools that were classified as kindergartens in 2012 (Chen and Li in press).

Birth rates from 2000 to 2014 are displayed in Table 11.2. As shown in the table, the number of children born declined from 305,312 in 2000 to 210,383 in 2014. A slight increase in births was observed following the historic low 7.21 % birth rate in 2010, but the birth rate in Taiwan has remained under 10 % from 2004 onwards.

Logically, a decrease in the number of children born should correspond to a decrease in that of children enrolled in kindergarten. With the decrease in target population and the increase in the number of kindergartens, ECE services should be increasingly accessible in Taiwan.

We find support for increased accessibility by examining the numbers of kindergartens, kindergarten teachers, and students (see Table 11.3). The number of students enrolled in kindergartens averaged at 213,989 in the years prior to 2012. However, following the integration of kindergartens and day-care centres in 2012, student enrolment became more than doubled, reaching 459,653 children (MOE 2013). As of 2014, there were 6,468 schools and 444,457 enrolled students throughout Taiwan, indicating that on average, the ratio of school to child was v1:68.7 (i.e. there was one kindergarten for approximately every 69 children). Of course, given that schools and students are not evenly distributed throughout Taiwan, the ratio only provides a general sense of the availability of kindergartens for Taiwanese children.

Finally, we examine whether every kindergarten-aged child can easily attend a nearby kindergarten in one’s district. Referring to the latest statistics from the MOE (2015a, b) shown in Table 11.4 (cities and counties listed in alphabetical order), there are on average more kindergartens per 1,000 km in the cities (950.96) than in the counties (146.11). In particular, Taipei City, the capital of Taiwan, has an extremely large number of kindergartens (2,604.86 schools per 1,000 km), while Hualien County, one of the larger, more rural counties in eastern Taiwan, has a much lower number of kindergartens (28.73 schools per 1,000 km). The difference in kindergarten numbers may be related to the number of eligible young children living in the area (i.e. there are more kindergarten-aged children in cities than in counties), but a closer investigation by county, city, and district is needed to evaluate accessibility in further detail.

Affordability: Increasing Financial Support to Relieve Parental Burden

In the past decade, the Taiwanese government has increased efforts to make ECE more affordable to families of young children. The tuition fees for private kindergartens skyrocketed in the 1990s (Ho 2006), creating a financial burden for parents who were unable to enrol their children in public kindergartens. To address this problem, the government began building additional public kindergartens (Ho 2006) and creating government-supported, privately-operated kindergartens in the early 2000s (Chen and Li in press; Lin 2007). The increase in kindergartens supported by the government – which offer lower tuitions relative to kindergartens that are completely privately run – meant that ECE became much more affordable for families.

To boost both the accessibility and affordability of ECE, the MOE (2008) increased financial support, first to 5-year-old children from economically disadvantaged families in 2004 and then to all families with 5-year-old children in 2007. A voucher programme was launched in 2007, providing 10,000 New Taiwan dollars (NTD; about 333 US dollars, or USD) per year for each student. Although this additional subsidy covered a small fraction (approximately 5–15 %) of the total kindergarten tuition cost, it nevertheless demonstrated a commitment from the Taiwanese government in making kindergarten education affordable, especially to low-income families (Chen and Li in press).

In 2008, the newly elected President Ying-Jeou Ma proclaimed that the government, in lieu of continuing the voucher programme, would commit to making ECE free for all 5-year-old children in Taiwan (MOE and MOI 2011). Eligible children (i.e. those who would be aged 5 by the time they enrolled in kindergarten) attending public kindergartens would have their tuitions fully covered, and those attending private kindergartens would have their tuitions partially subsidized (Chen and Li in press; MOE 2008). Financial support for private kindergartens was further increased in 2011 (MOE and MOI 2011). Finally, extra resources (e.g. subsidized travel costs, after-school programme fee support) were provided to children from ethnic minority backgrounds and those from rural areas (Chen and Li in press). In summary, the government has made an explicit effort over the past years to ensure that ECE is affordable to all qualified young children.

We also examine the affordability issue by looking at the average household income. Specifically, we use the Gini coefficient to compare the household income distribution in Taiwan with those from other Asia-Pacific regions. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Gini coefficient represents the income distribution of a nation’s population by measuring the extent to which the distribution of income or consumption expenditure among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution (OECD 2015a, b). A Gini coefficient of 0 means that there is perfect equality of income distribution; on the other hand, a Gini coefficient of 1 means extreme inequality in the distribution of income in the population.

The National Statistics of Taiwan (2012) and OECD (2015a, b) showed that the latest Gini coefficient of Taiwan was 0.29 in 2012, indicating that the income distribution is more equal relative to comparable Asian countries, such as South Korea, Japan, and Singapore (see Table 11.5). From this comparison, we can infer that families in Taiwan have fairly similar financial capacities for consumption (Leung 2014). This relative equality in income distribution indicates that the financial needs of kindergarten-aged children can be addressed with broad, nationwide policies, as long as these policies are based on the average household income.

In addition to the economic well-being of individual households, the overall economic health of a region is critical in understanding affordability. To examine this issue, we turn to the consumer price index (CPI), which measures changes over time in the general level of prices of goods and services that a reference population must spend for consumption (OECD 2015a, b). The CPI for Taiwan from 2000 to 2014 (Taiwan Directorate General of Budget and Accounting and Statistics 2012) is shown in Table 11.6. The price index shows gradual inflation, with a rising rate of 15 %, from 89.82 to 103.36, throughout the past 14 years. Therefore, given the gradual and steady rate of inflation, adjusting the governmental subsidies to maintain the affordability of Taiwanese kindergartens should be manageable in Taiwan.

Accountability: Making Quality Assurance Matter

Quality assurance is important to consider when ECE is delivered. Although previous research has indicated that participation in ECE services is preferable to no participation at all, children who are enrolled in schools that are regulated and monitored still outperform their peers in schools that are more informally run (Rao et al. 2012). As a result, it is important to consider the factors that contribute to a high-quality education: the number of students per class, the ratio of students to teachers, and the curriculum offered to the students.

With the increase in the number of available kindergartens and the decline in birth rate, the current number of students per class should be low relative to the years before 2000. However, although student enrolment should be regulated by the government, it can be difficult to monitor in actuality. Although many schools providing ECE services are either fully or partially supported by the government, the number of private schools has far exceeded the number of public schools in the recent years. As of 2013, there was more than double the number of private schools compared to public schools (see Table 11.1). Along with the dramatic increase in the number of kindergartens in 2012, the number of certified kindergarten teachers rose sharply, from 14,918 in 2011 to 45,004 in 2012 (see Table 11.3). The addition of these teachers correlates with an improvement in the student-teacher ratio, from a ratio of 12.1:1 in 2000 to 9.78:1 in 2014. With the shift in student-teacher ratio, quality education should have become more accessible to young children.

Compared with public kindergartens, private kindergartens – as profit-making organizations – are obligated to pay business taxes and higher utility fees (Ho 2006). As a result, private kindergartens often enrol more students than permitted by governmental regulations; some schools even fail to register with the government, operating underground to avoid legal paperwork and to keep their cost of operations at a minimum (Ho 2006). To improve the accountability of the private kindergartens, the MOE in 2004 started promoting the creation of government-utility, privately-operated kindergartens (Huang and Hsu 2004). These private kindergartens, built on publically owned land, could then be more closely monitored by the local government in each city or county (Chen and Li in press). In 2011, the MOE proposed two more types of schools to provide additional ECE options to families in need (MOE 2012). National experimental kindergartens, the first type, are created as kindergartens affiliated with public primary schools, typically located on the primary school campus. Private non-profit kindergartens, the second type, involve close maintenance and support from the local education departments and professional ECE personnel teams. These types of kindergartens allow for more schools to be regulated by the government.

To address the quality of teaching and curriculum in ECE, the Taiwanese government now requires kindergartens to (a) be accredited, (b) be evaluated regularly, and (c) hire qualified ECE professionals. The accreditation process can include evaluations of the school administration, teaching and caring, teaching facilities, and public safety (Lin 2007). Kindergartens must also undergo regular evaluations every 3–5 years (Hsu 2003). In these evaluations, the quality of administration, course content, educational materials and facilities, safety measures, and degree of integration with the community are all reviewed (Hsu 2003). Lastly, the requirements for becoming an ECE teacher have been tightened over the years (Chen and Li in press). Aspiring teachers must now finish a professional programme focusing on ECE, intern at a kindergarten for 6 months, and pass a qualification exam before they can become a full-time teacher in public kindergartens (Lin 2012). Finally, according to the Early Childhood Education and Care Act (ECECA), in-service kindergarten teachers are required to fulfil an 18-h training programme every year (Laws and Regulations Database of The Republic of China 2011).

The government has struggled with developing an appropriate curriculum for ECE. The Standards of Kindergarten Curriculum, established in 1987, no longer provides adequate guidance to kindergartens (Chen and Li in press; Lin 2002). Schools largely create their own curricula, drawing from traditional Chinese teaching methods (e.g. completing practice worksheets; Lin and Tsai 1996) and Western philosophies (Wei 1995). These school curricula are not well monitored by the government or ECE professionals, and teachers often struggle to balance between academically oriented and child-centred approaches in the classroom (Lu 1998). Currently, the MOE has provided support to kindergartens through its governmental website (http://www.ece.moe.edu.tw/).

Kindergarten principals and teachers are encouraged to download teaching and parenting resources, review regulations and assurance frameworks, and provide accommodation services of education and care to children. However, more research, training, and guidance are needed to better align an appropriate ECE curriculum with the needs of Taiwanese children.

Sustainability: Investing Extra Fiscal Input to Develop Quality Education

Increasing the accessibility, affordability, and accountability of ECE would mean very little if the results of these efforts are not sustainable over time. Traditionally, one of the heaviest fiscal burdens for county and municipal governments is educational expenditure, which includes early childhood and primary and secondary schools (Chen 2014). Arguably, then, fiscal input provided to kindergartens (public and private) should contribute to sustainability by providing additional resources and alleviating financial burdens for the schools. In exchange, schools should be motivated to keep their services accessible and affordable to students and to be accountable to governmental regulations (Leung 2014).

Thus, we turn to the key education finance reforms that have been introduced in recent years, investigating whether and how fiscal input from the federal government impacted the sustainability of education development. Historically, total expenditure for education, science, and culture was not to exceed 15 % of the annual federal government budget, 25 % of the annual county government budget, and 35 % of the annual municipal budget (Chen 2014). In 2011, reforms on education finance began with the passing of the Compilation and Administration of Education Expenditures Act (CAEEA), which raised the minimum level of federal educational expenditure for all sectors of education to 22.5 % of the average net annual revenue over the previous three budgeting years (Laws and Regulations Database of The Republic of China 2013). The CAEEA also provided more specific guidelines on the amount of expenditure to different sectors of education.

Examining the composition of educational expenditures by level of education from 2000 to 2013 (MOE 2013) suggests that the Taiwanese government has paid increasing attention to ECE. Even though ECE does not share a large proportion of the national educational expenditure, it is the only sector whose expenditure has been more than doubled, rising from 2.85 % to 6.9 % between the years 2000 and 2013 (see Table 11.7).

Similarly, in examining the educational expenditure per student at all school levels, we find that the magnitude of expenditure increase at the kindergarten level was the largest, increasing from 62,000 to 112,000 NTD (i.e. approximately 2,067–3,733 USD) from 2000 to 2013 (MOE 2013; see Table 11.8). From the fiscal years 2000 to 2013, the amount of educational expenditure increased steadily across all levels, allowing ECE schools to remain well supported for the foreseeable future (MOE 2013).

Social Justice: Balancing Resources for All Stakeholders

Finally, we review how the Taiwanese government has addressed issues of social justice through their policies on ECE. In the government’s policies on increasing accessibility and affordability, attention has been consistently given to children from economically disadvantaged families, those living in rural areas, and those who are members of ethnic minority groups (Chen and Li in press; Lin 2007; MOE 2008; MOE and MOI 2011). Additional financial support (ranging from 400 USD to 1,000 USD) has been given to children from low socioeconomic backgrounds, even if they were enrolled in private kindergartens (Chen and Li in press; MOE 2011; MOI 2011).

Schools have also been encouraged to be attentive to social justice issues, ensuring equal opportunities for children of different gender, ethnicities, and cultures (MOE and MOI 2011). For instance, schools are encouraged to educate children belonging to ethnic minorities in their mother tongue (e.g. Taiwanese, Hakka, aborigine languages). In addition, children with learning exceptionalities should be supported by professional intervention teams. Other policies related to social justice include the following: (a) a counselling mechanism to guide and support teachers working in remote communities; (b) a database of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families, to be used to evaluate policy effectiveness for vulnerable children over time; and (c) a priority to provide social welfare support to families with economic difficulties (MOE and MOI 2011). These policies indicate much willingness from the government to address inequities in the Taiwanese society.

However, more can always be done, especially from the perspective of other ECE stakeholders. There was a large-scale protest (including over 10,000 teachers, parents, and children) in March 2015 as the ECECA was due for a review by the Legislative Yuan. Specifically, concerns were raised over the plans to build approximately 100 government-utility, privately-operated kindergartens (i.e. private kindergartens that would be built on publically owned land) in the coming 5 years.

Since the government did not explicitly prohibit public kindergartens from being transformed into such schools, teachers and parents were concerned that a number of public kindergartens, already built on government-owned land, would make the transition, thus allowing these schools to operate with less governmental supervision. Although these schools would still be monitored by the government, many stakeholders worry that these semipublic kindergartens may eventually compromise educational quality for profit, making ECE less accessible and affordable to students (Lii 2015a, b).

Additionally, the integration of kindergartens and day-care centres has created new challenges for ECE stakeholders. Although this integration has allowed for more accountability from kindergartens and former day-care centres, it has also created a rift in the ECE field from the perspective of the teachers. Before, childcare workers were responsible for children in the day-care centres, even though the majority of these workers were not formally trained in ECE. Once day-care centres became kindergartens, however, these childcare workers, now officially unqualified to manage a classroom on their own, could only assist the trained teachers. This perceived demotion rankled many childcare workers, especially those who had accumulated numerous years of experience, and many educators argued that the integration of the ECE system resulted in the inequitable treatment of these workers (Lii 2015a, b). Without resolving the concerns over semipublic kindergartens and childcare workers, these issues may critically affect the quality of Taiwanese kindergarten education for all children, but particularly those from disadvantaged families who may rely on their schools to supplement their early childhood experiences (“Millions of people go on the streets to protect early childhood education”, “Revising laws with conscience”, “Protest from all citizens to protect early childhood education”, 2015).

Conclusion

To summarize, ECE in Taiwan has undergone waves of development since the first kindergarten was established in the early twentieth century, but efforts to reform ECE have been particularly dramatic and far reaching since 2000. In our chapter, we examined the governmental policies and laws, various governmental statistics, and local media coverage of ECE through the 3A2S framework. Through our investigation, we believe that the reforms enacted by the Taiwanese government – on the federal as well as at the county level – have largely improved ECE in Taiwan.

To make kindergartens more accessible and affordable, the government enacted one of the most influential policies in the past decade: launching free education for children who are 5 years of age. In addition, the government has added public kindergartens to the ECE system and provided land for private organizations to build kindergartens that would be more affordable to families of young children. To address accountability issues, the government has sought to integrate the day-care and the kindergarten systems, to ensure that ECE teachers are properly certified, and to encourage kindergartens to use curriculum that is appropriate for young children. The recent increase in governmental funding for Taiwan ECE is an indication of the government’s commitment to make the ECE reforms sustainable in the long run.

Finally, ECE policies have increasingly aimed to aid the needs of children from disadvantaged families – families of low socioeconomic background, from rural areas, and of ethnic minority or aborigine descent – so that from the very beginning of children’s lives, issues of social justice can be targeted.

Recent media coverage on the ECE sector clearly indicates that there is more to study and accomplish. Research on the distribution of kindergartens at the district or even neighbourhood level, for instance, is needed to understand more deeply the accessibility of kindergartens for children across Taiwan. Interviews with the families of different backgrounds should be conducted to see whether the recent policies have been able to alleviate the financial burdens of sending their children to school.

Similarly, interviews, focus groups, and surveys can be conducted with teachers and principals – both in public and in private kindergartens – to examine how the policies have affected educators at the ground level. Curriculums, both international and local, should be studied carefully to find a balance that can truly prepare children for their lives ahead. By understanding ECE issues from the perspectives of different stakeholders, we can gain insights into how the government can further enhance teaching and learning for young Taiwanese children.

In conclusion, the policies from the past decade have yielded an ECE system that better serves the children of Taiwan. The Taiwanese government has demonstrated a clear recognition of the importance of ECE and has shown its determination to improve the quality of ECE in the coming years. We anticipate further reforms down the road and also hope that other scholars will continue to monitor, examine, and evaluate the effectiveness of the recent ECE policies, ensuring that the children of Taiwan are well prepared for the future.

References

American Institute in Taiwan. (2012, February 8). Taiwan economic and political background note. Retrieved from www.ait.org.tw

Chen, L. J. (2014). A decade after education finance reform in Taiwan: In retrospect and prospect. Paper presented at 39th annual conference of the association for education finance and policy, San Antonio.

Chen, E. E., & Li, H. (in press). Early childhood education in Taiwan. In N. Rao, J. Zhou, & J. Sun (Eds.), Early childhood development in Chinese societies. New York: Springer.

Chiu, P. C. P., & Wu, Y. S. (2003). On the voucher policy of early childhood education in Taiwan. Paper presented at 幼兒教育與剬共政策:從比較角度看 台灣個案論文集,國立中正大學剬共政策及管理研究中心主辦 [Forum on early childhood education and public policy: Examining the case of Taiwan from a comparative perspective, organized by the National Chung Cheng University Research Center for public policy and management], Chiayi, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Ho, M. S. (2006). The politics of preschool education vouchers in Taiwan. Comparative Education Review, 50(1), 66–89.

Hsu, Y. L. (2003). 幼稚園評鑑方案的設計與實施建議 [Recommendations for the design and implementation of kindergarten evaluation]. 國教世紀 [National Education Century], 206, 73–78.

Huang, Y. J., & Hsu, M. R. (2004, October 17). Early childhood education law amended to allow for government-utility, privately-operated kindergartens. Enoch Times. Retrieved from http://www.epochtimes.com

Info Taiwan. (2015). Who we are: About Taiwan. Retrieved from http://www.taiwan.gov.tw/

Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China. (2011). 幼兒教育及照顧法 [Early Childhood Education and Care Act]. Retrieved from http://law.moj.gov.tw/

Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China. (2012a). 托兒所及幼稚園改 制幼兒園辦法 [Regulations regarding the restructuring of preschools and kindergartens]. Retrieved from http://law.moj.gov.tw/

Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China. (2012b). 幼兒園評鑑辦法 [Regulations regarding the evaluation of preschools]. Retrieved from http://law.moj.gov.tw/

Laws & Regulations Database of The Republic of China. (2013). 教育經費編列與管 理法 [The Compilation and Administration of Education Expenditures Act]. Retrieved from http://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=T0020018

Leung, S. K. Y. (2014). Evaluating the free early childhood education policies in Taiwan with the 3A2S framework. International Journal of Chinese Education, 3(2), 268–289.

Li, H., & Wang, X. C. (in press). International perspectives on early childhood education in Chinese societies. In N. Rao, J. Zhou, & J. Sun (Eds.), Early childhood development in Chinese societies. New York: Springer.

Li, H., Wong, M. S., & Wang, X. C. (2010). Affordability, accessibility, and accountability: Perceived impacts of the pre-primary education vouchers in Hong Kong. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(1), 125–138.

Lii, W. (2015a, January 15). Childcare activists target ‘public-private’ plan. Taiwan News. Retrieved from http://www.taiwannews.com.tw

Lii, W. (2015b, January 22). Preschool teachers protest outside education ministry. Taiwan News. Retrieved from http://www.taiwannews.com.tw

Lin, Y. W. (2002). Early childhood services in Taiwan. In L. K. S. Chan & E. J. Mellor (Eds.), International development on early childhood services (pp. 195–210). New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Co.

Lin, Y. W. (2007). Current critical issues of early childhood education in Taiwan – reflections on the social phenomenon and governmental policies. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago.

Lin, Y.W. (2012). The paths to high quality early childhood teacher education and professional development – Taiwan experience. Paper presented at the international seminar and workshop on “Early childhood education for a better nation”, Semarang.

Lin, H. F., & Ching, M. J. (2012). Managing the Taiwan kindergarten evaluation system. International Journal of Research Studies in Management, 1, 77–84.

Lin, Y. W., & Tsai, M. L. (1996). Culture and the kindergarten: Curriculum in Taiwan. Early Child Development and Care, 123(1), 157–165.

Lin, T. Y., & Yang, S. C. (2007). The trace of early childhood education. 社會變遷 下的幼兒教育與照顧學術研討會論文集 [Academic papers on the effects of social change on early childhood education and care] (pp. 5–14).

Lu, M. K. (1998). The curriculum and learning evaluation of open style kindergarten education. Taipei: National Science Council. (In Mandarin).

Millions of people go on the streets to protect early childhood education. (2015, March 8). Liberty Times Net. Retrieved from http://www.ltn.com.tw/

National Statistics of Taiwan. (2012). Income distribution in selected countries. Retrieved from http://win.dgbas.gov.tw/fies/doc/result/101/a11/Year08.xls

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2015a). Glossary of statistical terms. Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=4842

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2015b). OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD): Gini, poverty, income, methods and concepts. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm

Protest from all citizens to protect early childhood education. (2015, March 8). China Daily News. Retrieved from http://www.cdns.com.tw/

Rao, N., Sun, J., Pearson, V., Pearson, E., Liu, H., Constas, M. A., & Engle, P. L. (2012). Is something better than nothing? An evaluation of early childhood programs in Cambodia. Child Development, 83, 864–876. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01746.x.

Revising laws with conscience. (2015, March 8). United Daily News. Retrieved from http://udn.com/news/index

Taiwan Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. (2012). Splicing table of consumer price indices. Retrieved from http://eng.stat.gov.tw/public/data/dgbas03/bs3/english/cpiidx.xls

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (2008). 扶持5歲幼兒教育計畫 [Plan to support the education of 5-year-old children]. Retrieved from http://www.cbi.gov.tw/CBI_2/upload/bd07bd4c-813f-4345-a1c9-d2f0350e85dc.pdf

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (2012). Summary of kindergartens – By public or private (SY 2011–2012). Retrieved from www.edu.tw/files/site_content/b0013/k.xls

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (2013). 教育統計指標:教育經費:各級學校經費結 構 (101 學年度) [Composition of educational expenditures by level of education (School year 2012–2013)]. Retrieved from http://stats.moe.gov.tw/files/ebook/indicators/101indicators.xls

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (2015a). 教育統計指標:教育發展:學前教育-幼兒 園 (103 學年度) [Number of preschools (School year 2014–2015)]. Retrieved from http://stats.moe.gov.tw/files/ebook/indicators/103indicators.xls

Taiwan Ministry of Education. (2015b). 全國教保資訊網 [Early childhood educare]. Retrieved from http://www.ece.moe.edu.tw/

Taiwan Ministry of Education & Ministry of the Interior. (2011). 5歲幼兒免學費教 育計畫 [Plan to provide free education to 5-year-old children]. Retrieved from http://www.edu.tw/files/list/B0039/5歲幼兒免學費教育計畫【100學年修正計畫發布版100824】.pdf.

Wei, M. H. (1995). Current trends of philosophies in early childhood education. Taipei: Hsin-Lee. (In Mandarin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

- 3A2S:

-

Accessibility, affordability, accountability, sustainability, social justice

- CAEEA:

-

Compilation and Administration of Education Expenditures Act

- CPI:

-

Consumer Price Index

- DPP:

-

Democratic Progressive Party

- ECE:

-

Early Childhood Education

- ECECA:

-

Early Childhood Education and Care Act

- KMT:

-

Kuomintang

- MOE:

-

Ministry of Education

- MOI:

-

Ministry of the Interior

- NST:

-

National Statistics of Taiwan

- NTD:

-

New Taiwan Dollar

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- SKC:

-

Standards of Kindergarten Curriculum

- USD:

-

United States Dollar

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leung, S.K.Y., Chen, E.E. (2017). An Examination and Evaluation of Postmillennial Early Childhood Education Policies in Taiwan. In: Li, H., Park, E., Chen, J. (eds) Early Childhood Education Policies in Asia Pacific. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, vol 35. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1528-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1528-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-1526-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-1528-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)