Abstract

A large segment of New Zealand’s population is made up of foreign-born individuals. Despite the significant role that foreign-born individuals play in New Zealand society, relatively little research has been done to address the impact of immigration on the labour market. In this chapter, we re-examine the impact of immigration in New Zealand using a panel of individual-level New Zealand Income Survey data and a national-level methodology. We extend the model to include regional effects, and we incorporate measures of effective immigrant work experience, which reflect the values placed on immigrants’ human capital (work experience) in the host country. We find that immigration has little impact on earnings and employment hours. The results further confirm that the effective experience measure improves the precision of the immigration impact estimates.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

More than a quarter of New Zealand’s population consists of immigrants. At the time of the 2018 Census of Population and Dwellings, 27% of New Zealand’s resident population was born in another country. The impact from the inflow of migrant workers on the labour market is of special interest. A key question is whether or not immigration affects wages and opportunities in the domestic labour market. Do they raise or drive down the wages and employment of pre-existing workers? If immigration raises income and productivity in the economy, then government policy should facilitate the economic gains by encouraging immigration. However, if immigration decreases income and productivity in the economy, then policy may be required to limit immigration or attract only migrants who will positively contribute to the economy.

Despite the large inflow of migrants in the last decade, little research has been done to address the impact of immigration on pre-existing labour market opportunities in New Zealand. The few studies that have examined this issue find small positive effects (see Maré and Stillman 2009; Maani and Chen 2012; Leem 2008). This chapter re-examines the impact of immigration in New Zealand using the national-level methodology introduced by Borjas (2003). Individual-level data from the New Zealand Income Survey (2002–2007) are analysed at the national level. We define skill groups based on education and work experience, and examine the changes in the economic opportunities for these pre-existing skill groups that are due to the supply of immigrant workers. This approach is appealing because at the national level, any internal movement of pre-existing workers does not dilute the estimated results.

Economic theory tells us that the impact of immigration depends heavily on the degree of substitution between pre-existing and immigrant workers. If the degree of substitution is high, then pre-existing workers face greater competition from immigrants and this may lead to adverse outcomes for the former. Using a congruence coefficient, we explore the correlation between native-born and immigrant workers, defined by skill groups and their occupational distributions. The results from this analysis indicate that workers with higher education have a higher occurrence of employment in the same occupations. However, complementarity may also be greater among high-skilled workers due to conglomeration and knowledge spillovers. Therefore, the question is to be answered empirically.

Applying a panel analysis of skill groups, we estimate the effects of immigrant supply shocks on domestic earnings and employment. The basic results indicate that immigration causes little impact on the economic opportunities of pre-existing workers.

We apply two extensions of the national-level model that make the results more precise. These extensions are regional impacts and extended specifications to incorporate immigrant effective work experience. First, the distribution of migrant workers in New Zealand is asymmetric amongst the various regions. For example, the population census shows that more than 40% of the immigrant population resides in Auckland. Since immigrant workers are unevenly distributed throughout the country, it is interesting to examine skill groups within geographic boundaries. By differentiating the analysis of skill groups by regions, we are able to isolate labour market outcomes due to immigrant supply shocks for regions where the supply shock is greater.

Second, the analysis in this chapter approaches workers/immigrants from the point of view of their human capital. The standard approach of such analyses has ignored the market value of different types of human capital. However, employers value skills acquired in the domestic environment differently to skills acquired in a foreign setting. To capture the various market values of human capital, we introduce the concept of ‘effective experience’ as defined in Borjas (2003). In effect, we are using more realistic measures of human capital and this enables us to produce more accurate estimates of the impact of immigration. Using the effective human capital framework, the estimates of the impact of immigration become negative. However, even though the outcomes are adverse, the absolute sizes of the effects remain small. Overall, the results indicate that the impact of immigration is small and close to zero.

The rest of the chapter is organised as follows: Section 10.2 examines the literature on the impact of immigration on labour market outcomes. Section 10.3 examines the New Zealand labour market data and discusses trends in common economic measures. Section 10.4 introduces the methodology of the national-level approach. The section also examines the index of congruence between immigrant and native workers. Section 10.5 reports the estimates of the impact of immigration and the two extensions of the national-level model that make the results more precise. Section 10.6 summarises the chapter.

2 A Review of the Literature

The impact of immigration on domestic labour market outcomes is a topic that has received much attention in most developed countries. There have been many attempts in the literature to estimate the changes in labour market outcomes of pre-existing workers due to the inflow of immigrant workers, but there is no consensus on the labour market impacts of immigration. For example, Altonji and Card (1991), Card (1990, 2001), Dustmann et al. (2005, 2008), Jean et al. (2010) and Docquier et al. (2013) find little impact on native earnings from immigration; Borjas (2003, 2004, 2005), and Aydemir and Borjas (2011) find significant negative effects; and Mishra (2007) and Kifle (2009) find significant positive effects due to immigration. Unsurprisingly, the results differ across different countries, and it is of interest to see what results appear when this analysis is conducted on the New Zealand labour market.

The effect of immigration on labour market outcomes is not clear-cut. The inflow of immigrants may affect the earnings of existing workers in a negative or positive way. The direction of the impact is dependent on a number of factors: these include the substitutability between immigrants and natives, and the contribution of immigration towards aggregate supply and demand.

The elasticity of substitution is an important factor in determining of the impact of immigration on earnings. The basic textbook theory of demand and supply indicates that, holding all else constant, an increase in the supply of labour would decrease wages. Given that capital is held constant and there are constant returns to scale in production technology, this simple description is intuitively appealing—as a resource becomes less scarce, the value placed upon a unit of that resource becomes less. If immigrants and natives are substitutes, then the inflow of immigrants would reduce wages across groups (Borjas 2003; Orrenius and Zavodny 2007). The strength of the reduction to wages depends on the degree of substitution and it is most severe when immigrants and natives are perfect substitutes. However, if there is imperfect substitution between immigrants and natives, then the magnitude of wage reductions is smaller. Further, if immigrants complement native workers, then we would expect positive changes to earnings from immigration (Ottaviano and Peri 2012; Borjas et al. 2008). A complementary relationship raises the marginal productivity of labour in the economy and leads to positive economic outcomes for workers.

It should be noted that the elasticity of substitution is not constant across the entire workforce. The substitutability between immigrants and pre-existing workers is expected to vary across a number of different dimensions (Orrenius and Zavodny 2007; Dustmann et al. 2008). Considering the skill requirement specific to different industries, immigrants and pre-existing workers are more likely to be substitutes in industries that require less skill. However, it is more difficult to interchange immigrant and native workers in industries that demand a considerable amount of industry-specific skill and technical knowledge. Such industries may require a high degree of language proficiency and relevant domestic knowledge. Foreign training is likely to be of lower value than comparable local training and thus it is more difficult to substitute existing workers with immigrant workers in such industries.

Education and experience are also important factors in determining the degree of substitution between immigrants and pre-existing workers. It is well documented that the value placed on education and experience acquired abroad is often less than the value placed on domestic education and experience (Lalonde and Topel 1991; Duleep and Regets 2002; Akresh 2006; Antecol et al. 2006).Footnote 1 As a result, it is more difficult to transfer foreign work experience to the domestic labour market. In particular, high-skilled immigrants suffer a larger earnings penalty compared to their lesser skilled cohorts (Orrenius and Zavodny 2007). One of the implications of imperfect skill transferability for immigrants is that the pre-existing worker group that is impacted by the immigration inflow may possess fewer years of work experience.

An equally important factor is the change to aggregate supply and aggregate demand due to immigration. Immigration adds to the supply of workers and this leads to greater aggregate supply in the economy. However, the inflow of immigrants also increases aggregate demand, as immigrants are consumers of both public and private goods (Addison and Worswick 2002). If aggregate supply increases more than aggregate demand, then we expect reduced earnings and lower employment in the labour market. However, when the addition to aggregate demand from immigration exceeds the change to aggregate supply, positive economic impacts are expected. It is only possible to identify whether the supply or demand effect is stronger through empirical means.

An increase in aggregate demand encourages firms to expand production and capture larger economic benefits. To expand production, firms utilise high levels of the factors of production in which labour is an important part. Immigrants contribute to higher levels of aggregate demand through greater consumption of household and government goods and services; these may include housing and infrastructure. Thus, the wage that prevails in the labour market depends on the size of the effect of immigration on labour supply and labour demand.

In general, there are two major approaches to the study of the impact of immigration. The first is the spatial approach, which utilises geographic clustering and changes across local labour markets to determine the impact of immigration on wages (Altonji and Card 1991; Card 1990, 2001, 2005; Dustmann et al. 2005). This spatial approach assumes cities or regions within a particular country are discrete labour markets (Kifle 2009). The idea is that immigrant inflows change the wage structure within a labour market. Immigrant inflows that raise the number of workers in a particular group would depress wages in the labour market. By examining the changes across local labour markets, the empirical work of Card (1990, 2001, 2005) finds little impact from immigration on native earnings in the US labour market. Similarly, Dustmann et al. (2005) analyse British labour market data, Maré and Stillman (2009) analyse New Zealand Census data and Maani and Chen (2012) use New Zealand Household Labour Force Survey (HLFS) data and they all find little evidence of negative effects on employment and earnings based on the spatial approach.Footnote 2

The spatial approach is widely used, but there are a few weaknesses that should be considered. The main issue of spatial analysis is that it may ignore the movement of workers between local labour markets (Card 2001; Borjas 2003). The influx of immigrants may lower the wages in a particular local labour market and this encourages existing workers to internally migrate to other markets that have higher wages. If this situation prevails, then internal migration would equalise any reduction in earnings. There may also be a positive correlation between immigrants and wages (Borjas 2001, 2003). It may be the case that immigrants are attracted to cities or regions that have good economic progress. This would imply a positive bias from immigration in local labour markets where demand shocks raise wages and employment. This concern is addressed through the use of instrumental variables in local labour market analysis.

The second approach (which is used in this study) analyses the impact of immigration using national-level data and defining groups along the skills dimension (Borjas 2003, 2004, 2005; Orrenius and Zavodny 2007). The classic work of Becker (1975) and Mincer (1974) on human capital and earnings shows that the skills of workers prior to entry to the labour market and post-entry are important factors in the determination of earnings. We can interpret their findings as implying that both education and experience are important components in the labour market. Borjas (2003) defines immigrant and pre-existing groups by both education and experience to utilise the importance of both factors in wage determination. Borjas shows that immigration is not constant across all groups. This heterogeneous immigrant supply creates sufficient variation to estimate the impact of immigration inflows on the economic outcomes of pre-existing workers.

Using US Census and CPS data, Borjas (2003) finds significant negative effects on earnings and employment due to immigration.Footnote 3 Borjas (2004) also finds evidence that immigration causes earnings depression for pre-existing workers, regardless of including both the legal and illegal immigrants in the analysis, or only immigrants with legal status. Focusing on doctoral recipients, Borjas (2005) continues to find adverse effects from immigration. Evidence from the US suggests that immigration causes serious negative effects on the existing working population by as much as a 3% decrease in wages of competing workers for a 10% increase in the number of immigrant workers.

However, a review of studies that utilise similar methodology yields a wider range of results. D’Amuri et al. (2010) study German data and estimate the impact of immigration on the German labour market. These authors note that Germany is the European country that has the greatest immigrant population.Footnote 4 The authors also estimate the elasticity of substitution between immigrants and natives. The resulting estimate suggests less-than-perfect substitution between natives and immigrants.Footnote 5 Breaking down the analysis with respect to groups by education, D’Amuri et al. estimate that immigration causes a negative impact of around 1% on the highly educated group. For the less educated, the authors estimate a positive impact of a similar magnitude. Thus, the average impact of immigration is zero.

Ottaviano and Peri (2012) allow for imperfect substitution between immigrants and natives. After relaxing the typical assumption of perfect substitution, their results show positive wage effects from immigration. These results differ from earlier analyses that find significant negative effects on earnings (e.g. Borjas et al. 1996).

Analysing four different data sources from Spain, Carrasco et al. (2008) do not find significant negative effects of immigration on native employment or earnings.Footnote 6 However, Kifle (2009) examines the Australian labour market and finds a positive impact from immigration. The only negative results are found in low-skill occupations, but the author suggests that they are the result of a mismatch rather than a negative effect. Immigrants in low-skill occupations tend to be overeducated and as a result earn more than their native co-workers. Similarly, Mishra (2007) finds significant positive effects in the Mexican market.

Hence, there is no consensus as to the impact of immigration on pre-existing workers’ economic outcomes. It appears that the results are both country- and time-dependent. This conclusion is confirmed by international surveys such as Okkerse (2008) and by formal meta-analyses (Longhi et al. 2010). Such surveys find that the impact of immigration on the earnings and employment of the existing population is small and that it varies across countries.

Little work has been done with New Zealand labour market data on the effect of immigration on the labour market, despite New Zealand being a major immigrant-receiving country. This study follows the national-level framework (Borjas 2003) because it is intuitively appealing. However, the analysis is also extended to incorporate (1) regional impacts and (2) better measures of skill.

3 Data and Descriptive Analysis

This research utilises data from the 2002 to 2007 New Zealand Income Survey (NZIS). These are individual-level data released under the Confidentialised Unit Record File (CURF) format. The NZIS is run as an annual supplement to the Household Labour Force Survey (HLFS). The HLFS is a quarterly survey of approximately 15,000 households (29,000 individuals) that represent urban and rural New Zealand. The focus of the NZIS is to collect information on actual and usual earnings, employment and various components of income.

The analysis in this chapter is restricted to employed men. Individuals are defined as natives if they are born in New Zealand and immigrants, if otherwise. The focal point in this analysis is to examine education-experience groups over time rather than individuals. The time period of the data corresponds with a period of normal to buoyant economic and labour market conditions. The time period also signifies a period of stable prices (low inflation). Although the choice of the years of data is determined by data availability, the time period 2002–2007 is fortuitously outside unusual occurrences, such as the global financial crisis.

Workers are classified into four distinct groups: those without a high school degree; school qualifications (high school degree); post-school qualifications; and bachelor or higher degree. In the NZIS, individuals record their highest level of qualification rather than their years of completed schooling. This classification of education groups is similar to other studies, which also use comparable numbers of education categories—Borjas (2003) and Carrasco et al. (2008) use four education groups and D’Amuri et al. (2010) use three education groups.

We first use the conventional method of organising individuals into experience groups based on potential years of experience with eight experience groups corresponding to experience in increments of 5 years. Past literature has shown that workers with similar experience are more likely to influence the economic outcomes of each other (Welch 1979). So, by combining workers with similar years of experience, it is possible to capture similarities (Borjas 2003).

The New Zealand Income Survey provides information for deriving a measure of potential years of experience. At this stage, we use the simple conventional definition: experience is Age − A T, where Age is the age of the individual and A T is the age of entry into the labour market. The entry age of a worker depends on his/her level of education. Those with no school qualifications (without high school degree) have entry at 16 years of age; at 18 years for those with school qualifications; at 20 years for those with a post-school qualification; and at 22 years for workers with a bachelor or higher degree. The focus is on workers with experience between 1 and 40 years. Observations that include work experience of more than 40 years are dropped from the analysis to keep the results in this study comparable to other major studies. This results in a pooled sample of 35,381 employed males, of whom 7162 are immigrants (foreign born).

3.1 Supply Shock

Table 10.1 shows the percentage of the New Zealand population that is foreign born across the time period of the study and regions of New Zealand. It is readily apparent that immigrants comprise a significant proportion of the New Zealand population; the growth in the immigrant share of the population is significant on an annual basis; and while all regions of New Zealand have experienced increases in their immigrant proportion of the population, this change has varied across regions. As such, the data are particularly well suited to national-level analyses that also allow for regional impacts.

As Table 10.1 shows, the concentration of immigrants is highest in the Auckland region. In 2002, 37% of immigrants lived in Auckland and this proportion continued to rise in the following years. By 2007, 44% of the population residing in Auckland consisted of immigrants. The region with the next biggest immigrant population is Wellington, with 29% in 2007.

There are numerous reasons to explain this observation. Immigrants tend to reside in areas that have higher numbers of fellow immigrants with similar ethnicity (Eden et al. 2003; Wang and Maani 2014a, b). Also, they may be attracted to areas with good economic opportunities. Since Auckland is regarded as the economic powerhouse of New Zealand, it makes sense for immigrants to reside in Auckland. While Auckland has the greatest number of immigrants, from 2002 to 2007, there was a general upward trend in the immigrant population in all regions.

In addition, Fig. 10.1 shows the change in the immigrant proportion of the population across New Zealand regions between 2002 and 2007. All regions of New Zealand show significant immigrant supply shocks during the time period. The Auckland and Wellington regions experience increased immigrant population changes of over 7% over the 5-year period.

3.2 Statistics for Education-Experience Groups

It is interesting to examine how immigrants and natives are distributed along different qualification and experience levels. Table 10.2 shows the percentage of immigrants and natives in various categories of education and experience. The different population shares are calculated for 2002 and 2007. In general, most workers hold some sort of post-school qualifications; these include vocational training and trade qualifications. From 2002 to 2007, there was a 1% point decrease in the number of immigrant workers in the post-school qualification category. However, the bachelor or higher degree group saw almost a doubling of immigrant workers—from 17% in 2002 to 32% in 2007. This increase in skilled immigration reflects the intention of New Zealand’s immigration system. Looking at the native and immigrant shares in experience groups, there is a remarkably even and stable distribution of workers across years of experience.

Given the distribution of immigrants across experience and education groups, Fig. 10.2 is useful in showing the immigrant supply shocks for different education-experience groups for the years 2002 and 2007. The supply shock fluctuates between 10 and 20% across different experience levels. However, for the highly skilled groups (those with bachelor or higher degree), immigrants count for up to 40% of the group population. In particular, the largest immigrant supply in the highly skilled groups is those with 20–25 years of experience. This observation is not overly surprising, because New Zealand operates a skilled-immigrant targeted system. Preference is given to foreign workers who are highly skilled, so we expect immigrants to form a larger portion of the highly skilled workforce compared to the lesser skilled groups. Comparing 2002 and 2007, there is a noticeable increase in the share of immigrants in each education group. The exception is for those with less than high school qualifications, where the proportion of immigrants actually fell in 2007 relative to 2002.

One interesting question is whether or not native workers move out of regions where there is a large immigrant inflow. To examine this, we computed the percentage change in native population in each region for each year. We found that from 2002 to 2006, in contrast to the significant inflow of immigrants, there are minor changes in cross-region movements of the native population, and there are no distinct trends in these results. Therefore, the data do not support the concern that working age native workers change regions away from where there is an influx of immigrants.Footnote 7

4 Methodology

The analytical approach in this chapter follows the framework conceived by Borjas (2003) to examine the impact of labour supply shocks due to immigration on the labour market outcomes of pre-existing workers. As noted previously, the analysis employs national-level data from 6 years of the New Zealand Income Survey (2002–2007).Footnote 8 Workers are classified into skill groups based on two aspects of human capital: education and experience. This grouping of workers relies on the implicit assumption that even if workers have the same education, they are not perfect substitutes if they have different levels of experience. Similarly, workers with the same years of experience are not perfect substitutes if they have different levels of educational attainment.

Individuals are sorted into education-experience groups. There are four different categories of educational attainment: below high school qualification, high school, post-school (includes vocational and trade) qualifications, and bachelor or higher degree. In addition, we also define eight groups of experience levels.Footnote 9 This classification gives us 32 groups over 6 years, which is 192 cells in total (based on a pooled sample of 38,315 individual-level employed observations).

The main component of this model is an immigrant supply shock variable (Borjas 2003). For notation purposes, the cell (i, j, t) defines the educational attainment or qualification i, experience group j, and year t. The immigrant supply shock for a particular education-experience group in a particular period is defined as follows:

M ijt is the number of immigrants in a given education-experience time cell, N ijt is the number of native workers in the same cell. Eq. (10.1) shows the proportion of immigrants that make up a particular skill group at time t. In other words, the above fraction gives us p ijt, the immigrant supply shock variable.

This leads us to the basic empirical model in this chapter. We want to analyse the impact of immigrant supply on domestic labour market outcomes. The general approach is to regress the immigrant supply shock on pre-existing economic measures such as earnings and employment. More specifically, this analysis uses the following model, as seen in Borjas (2003):

The model includes the immigrant supply shock variable, p ijt. It also includes a number of fixed effects and interactions of these fixed effects. a i is the vector of fixed effects for education, b j indicates the work experience group, and c t is a vector for time periods. These fixed effects are important because they control for any differences across the various education groups, experience groups and also over time. It is also useful to control for changes in education and experience over time. (a i × b j) is the interaction term between education and experience. It controls for the different experience levels across the various education groups. (a i × c t) and (b j × c t) are interaction terms that control for education and experience changes over time. y ijt is the dependent variable. Three measures are used in this analysis: mean of log usual hourly earnings, mean of log usual weekly earnings, and mean of the fraction of hours worked in a week. Usual hourly and weekly earnings are deflated to 2002 levels.Footnote 10 The fraction of hours worked in a week is calculated as usual hours worked in a week divided by 40 h.Footnote 11 The inclusion of the above fixed and interaction terms implies that the variation in earnings and employment for a particular cell over time can be attributed to the impact from the immigrant supply shock variable.

Later in the chapter, we will use a more sophisticated definition of experience—effective experience, and there are other variations of Eq. (10.2) in later sections. These models incorporate additional variables and restrictions to ensure that the variation in the dependent variables can be correctly attributed to the variation from immigrant supply.

4.1 Index of Congruence

An important assumption of the model is that immigrants and natives who have similar education but different levels of experience are not perfect substitutes (Borjas 2003). Using an index of congruence (Welch 1979), it is possible to examine the degree of similarity between native and immigrant groups across the various occupations in the data. Consider two skill groups defined by education and experience and the number of natives and immigrants employed in these respective skill groups, disaggregated by occupation. Let a refer to natives and b to immigrants. The congruence coefficient is defined as follows:

\( {\overline{q}}_c \) is the fraction of the entire working population that is employed in occupation c. q ac is the fraction of natives in the selected skill group for natives that is employed in occupation c. q bc represents the fraction of immigrants in the selected skill group for immigrants that is employed in occupation c. The congruence coefficient G ab can be interpreted as a correlation coefficient of the fractions in various occupations between two groups a and b, for the selected two skill groups.

When the coefficient is one, the two groups have equal occupation distribution, and negative one means the two groups have completely different occupation distributions. The NZIS provides two-digit codes to classify individuals into different occupations.Footnote 12 The results from the table of congruence values show a distinct break between the highly skilled group and the other education groups (Table 10.3).Footnote 13

Notably, experience groups with a bachelor or higher degree all have positive congruence values. For instance, consider workers with a bachelor or higher degree and 11–20 years of experience. The congruence coefficient is 0.815; this is close to 1 and suggests that workers in this education-experience group are found in very similar occupations. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that the degree of substitution may be high for these workers.

For all non-bachelor/higher degree education-experience groups, the results confirm a negative congruence coefficient between immigrants and natives, implying that native workers and immigrant workers are in different occupations. While the index of congruence is by no means a complete measure of the degree of substitution between two groups of individuals, it offers a good indication of the groups that the analysis should focus on. In this case, the large positive coefficients for workers with bachelor or higher degrees suggest that it is worth examining these workers in greater detail.

5 Results

Table 10.4 shows the results from the estimation of Eq. (10.2). The estimation is based on the data for working men who have 1–40 years of experience. The three dependent variables are log weekly earnings, log hourly earnings, and fraction of time spent working. The table shows the coefficient β on the immigrant supply shock variable, and cluster robust standard errors. The standard errors on many of the coefficients in Table 10.4 are very large and this implies that the coefficients are insignificant. These initial results suggest that immigrant supply shocks have little effect on the earnings of pre-existing workers.

It is easier to interpret the values in Table 10.4 if they are converted to elasticities. These are also reported in the table [in brackets]. Looking at the impact of the supply shock on working hours, the elasticity of 0.11 indicates that a 10% increase in immigrant workers raises the fraction of hours worked in a week by 1.1%. However, the 95% confidence interval includes zero and hence we cannot reject the hypothesis that supply shocks have no impact on the hours of work.Footnote 14

5.1 Model Specification: Is the Fixed-Effects Model Correct?

It is important to test if the appropriate model is employed in this analysis. Generally, we expect the fixed-effects model to be correct since most studies utilise this approach. First we compare the fixed-effects and random-effects models. Using the Hausman test, the null hypothesis tested is that the coefficients in the random-effects and fixed-effects models are the same. The p-value of 0.02 suggests that we can reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients are the same, at the 5% level of significance. Hence, the fixed-effects model is more appropriate.

5.2 Education Groups

We also restrict the estimates by schooling groups to identify if the results are stronger for certain groups. Table 10.5 shows the results when the estimation is restricted to workers with similar educational attainment: those with no schooling (less than a high school degree); at least high school qualifications; and higher education. Elasticities are also reported for coefficients that are statistically significant (at least at the 10% level of significance). We find insignificant results for earnings and the hourly wage for all groups, but statistically significant results for employment outcomes.

The last column of Table 10.5 illustrates the results for the highly educated group. It is important to focus on this group because New Zealand operates a skilled-immigrant recruitment system. Immigrants account for a larger share of the skilled workforce than is the case for the lesser skilled workforce.

The estimated coefficients are positive and larger when we restrict the analysis to workers with higher educational attainment. Nevertheless, the absolute size of the elasticity of supply remains small and the large standard errors indicate that the impact of immigration is not significant. The results for the highly educated groups are not what we expect, since the index of congruence suggests that highly educated immigrants and natives are potentially more competitive than are other education groups. It may be the case that immigrant workers are not as readily substitutable to pre-existing workers in the highly educated groups, and this leads to small but positive effects from immigration. One explanation for these results is that immigrants lack characteristics that natives have. These may be proficiency in the domestic language, and less familiarity with local customs and experiences or complementarities among workers. We find generally similar results for the sub-sample of full-time men (last row of Table 10.5).

The following sections estimate the effect of immigrant supply shocks using different and more rigorous frameworks. It is useful to see how the results change and create a more robust illustration of how immigration may affect the economic outcomes of pre-existing workers.

5.3 Spatial Correlation

The first extension we apply is to combine the typical spatial approach with the education-experience groups’ approach of Borjas (2003). The spatial approach literature finds little impact from immigration (Dustmann et al. 2005) and the results presented so far also suggest that immigration plays a minor role in the labour market outcomes of pre-existing workers. It would be useful to see how the results change when skill groups are defined within each local labour market (regions)—does the impact on earnings become more positive? More negative? Or is there still no significant change?

To conduct this analysis, each cell is now defined as (r, i, j, t). That is, each cell is determined by a specific region, education level, experience group and year. The NZIS lists six local government regions in New Zealand: Northern North Island (Northland, Waikato, and Bay of Plenty); Auckland; Central North Island (Gisborne, Hawkes Bay, Manawatu, Wanganui, and Taranaki); Wellington; South Island (excluding Canterbury); and Canterbury. We know that immigrants account for approximately 10–20% of the working population in each region except in Auckland and Wellington. From 2002 to 2007, the immigrant share has risen from 21 to 29% in Wellington, and from 37 to 44% in Auckland (see Table 10.1).

Table 10.6 reports the results from region-education-experience-year analysis. Column (1) shows the base specification where only fixed effects are included—there are fixed effects for region, education level, experience, and year. The base specification shows the impact of immigration on skill groups within each region. The coefficients for the impact on earnings are both negative and significant.

The second column of Table 10.6 reports the results when two-way interaction effects are included. This is useful, as it controls for any changes in the labour market by education, experience and regions over time. Further, there are controls for interactions between region and education, region and experience and education and experience. These controls serve to improve the accuracy of the estimate of the impact of immigration on pre-existing workers’ outcomes. Again, the effect on earnings is negative. Weekly earnings fall by 1.4% for a 10% increase in the supply of immigrant workers and this coefficient is highly significant. When we consider the impact on hourly earnings, a 10% rise in supply reduces hourly earnings by 0.5%. Immigration also causes a negative effect on the working hours of pre-existing workers. Similar to before, the impact on employment is small and becomes insignificant.

The last column in Table 10.6 shows the estimates when three-way interaction terms are also included in the regressions.Footnote 15 We can isolate the variation in the shock from immigrant supply to the region-education-experience-year level through the inclusion of fixed effects and interaction terms. In other words, the impact of immigration on labour market outcomes is very specific. This specification should return even more accurate results than the first and second specifications. Surprisingly, the wage elasticity of supply remains similar to the previous results in columns (1) and (2). The impact on weekly and hourly earnings is −1.3% and −0.5% for a 10% increase in immigration. The impact on working hours is small and insignificant.

Overall, when we define skill groups by region as well, the earnings results become negative and mostly significant, at least at the 5% level of significance. When the size of the labour market is restricted by regional boundaries, the results are more definite. One explanation of this result is that Auckland and Wellington region have disproportionately more immigrants. Thus, by including regional labour markets in the analysis, the estimated effects are more representative of the uneven distribution of immigrants in New Zealand. This outcome is quite different from what Borjas (2003) finds in his analysis. In his paper, Borjas suggests that the inclusion of local labour markets conceals much of the impact from immigration. However, we are examining a different country and it is likely that there are fundamental differences in the structure of immigration between New Zealand and the US.

The impact of immigration changes in a number of ways when skill groups are distributed across local labour markets. At the national level, we find that immigrant supply shocks cause little effect on the economic outcomes. However, when skill groups are defined by regions, the estimated impact of immigration on earnings and employment becomes significant and negative.

We restrict the spatial approach to specific regions to identify if any specific local labour markets are driving the results. As suspected, when we restrict the analysis to Auckland, the sizes of the estimated coefficients become larger.Footnote 16

We can draw a number of interesting conclusions from the results in this section, and the regional statistics in the earlier sections. First, there is little indication of movement of native workers across different regions in New Zealand. This suggests that the inclusion of regions does not dilute the estimates of the effects from supply shocks. In fact, more precise results may be derived when we examine skill groups by regions compared to the national level. Second, the negative coefficients indicate that the inflow of immigrant workers is associated with small negative effects on wages and employment. Finally, because Auckland has the largest immigrant population, pre-existing immigrant workers in this region may suffer more adverse effects from immigration, compared to other regions in New Zealand.

However, when, in auxiliary estimates, we restrict the estimation to effects for the native-born sub-sample of the workforce, the coefficients for wage effects become significantly smaller in size, and they become insignificant for the native-born group. This result is consistent with the expectation that the wage effect observed in Auckland pertains to immigrant groups, including earlier immigrant groups for whom new immigrants are closer substitutes.

5.4 Defining Effective Experience

The analysis so far has the conventional measure of work experience as simply the age of an individual minus the age at which the individual enters the labour market. This is a very simple definition and is unlikely to be an accurate measure of experience. This approximation is reasonable for native men since it reflects their years of schooling and of workforce entry. However, this framework for experience is simplified because it assigns the same value to local and foreign experience. Employers in host countries are likely to place more value on domestic experience than foreign experience. We address this problem below.

Using US data, Chiswick (1978) finds that employers assign different values to foreign experience and local experience. It seems appropriate to redefine labour market experience as ‘effective experience’ (Borjas 2003). The objective is to define effective experience such that a year of foreign labour market experience is not the same as a year of domestic experience. Let X be the effective experience of an immigrant worker:

A m is the age of entry into New Zealand, A T is the age of entry into the labour market, and A is the age of the individual. So, if an individual migrated as an adult, then A m > A T and their experience would comprise two components: experience acquired abroad (A m − A T) and experience acquired since migration to New Zealand (A − A m). The coefficient α measures the value that New Zealand firms place on foreign experience and μ values local labour market experience. However, if an immigrant migrated as a child, then A m ≤ A T. Child migrants would acquire only domestic experience (A − A T). The coefficient τ measures the value of experience acquired by immigrant children.

The three coefficients above (α, μ, τ) can be estimated easily. Using all 6 years of the NZIS, we can run a standard immigrant assimilation regression of the formFootnote 17:

The dependent variable w is the log of weekly wage. s i is the fixed effects for education. I c = 1 if an immigrant entered as a child, I d = 1 if entry as adult an N is the indicator for native-born individuals. The term Y indicates the year of entry into New Zealand. Notice that the square of each of the three experience terms is also included in the regression. In effect, there are three sets of regressions being performed. Table 10.7 reports the results from this estimation of the relevant parameters.Footnote 18

The parameters of interest are the φ’s. φ n is the value employers place on a year of experience that a native worker acquires or, put differently, it is the market value of a year of native experience. φ c gives the market value of a year of experience acquired by an immigrant who entered as a child. φ d0 is the value of a year of foreign experience and φ d1 is the value assigned to a year of domestic experience acquired by immigrant workers. These values allow us to define the effective experience coefficients:

Using the estimated values reported in Table 10.7, we can compute the effective experience coefficients.

The first thing to note is that the market values for experience acquired by natives and for experience acquired by child immigrants are similar. In fact, slightly more value is placed on the experience acquired by child immigrants than comparable natives. This is implied by the coefficient τ = 1.1. As expected, the value assigned to local experience acquired by adult immigrants is less than that assigned to native or child immigrant experience. Further, foreign experience has the lowest market value of 0.035. Thus, the coefficients in question are α = 0.4 and μ = 0.7.

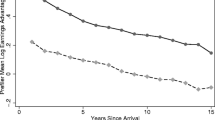

With these estimated coefficients, it is possible to calculate the effective experience for each worker in the sample. Instead of assigning workers to experience groups, we now assign workers to effective experience groups. Figure 10.3 shows the immigrant supply shock for each education group and effective experience level. The distribution of immigrant share in each education-experience group is quite different from before, as shown in Fig. 10.1.

There are now obvious trends in the supply shock. In the bachelor or higher degree group, immigrants account for almost 60% of workers with 10 years of experience. As the years of experience increase, the immigrant share falls. In the group of workers with school qualifications or post-school training, immigrants account for 40% of the workers with 10 years of experience and this falls as experience increases. Defining skill groups with effective experience has increased the size of the immigrant supply shock in general and there are obvious ‘peaks’ in the distribution.

Table 10.8 reports the results of running Eq. (10.2) again, but with effective experience groups rather than groups established under the standard definition of experience. The first obvious difference is that the impact of immigration on weekly earnings and working hours is now negative. The coefficient, when weekly earnings is the dependent variable, is −0.281 and this is highly significant. Translating this coefficient into an elasticity of supply interpretation, we have a 1.6% fall in earnings when the supply of immigrants increases by 10%. Notice that the other coefficients are very small in value and mostly insignificant. Overall, when defining skill groups by effective experience, the impact of immigration is small, but it tends towards a negative outcome. This is different from the results found when using the base specification, where the impact of immigration is minor, but tends towards a positive outcome.

The standard definition of labour market experience is too simple and does not reflect the value employers place on different types of experience. Thus, it makes sense to create a framework that allows domestic and foreign experience to be valued differently. Utilising this effective experience framework, while the sizes of the coefficients are small, the standard errors indicate that the effects on weekly earnings are significant.

Again, when in auxiliary analyses we restrict the estimation to wage and employment effects for the native-born sub-sample of the workforce, the coefficients for wage effects become significantly smaller in size and they become insignificant, indicating that the wage effect observed reflects results for the group of earlier immigrants, for whom new immigrants are closer substitutes.

6 Summary

In this chapter, we examine the impact of immigration on labour market outcomes in New Zealand. With so much interest in the impact of immigration, and given that immigrant workers form a substantial segment of the New Zealand workforce, this topic is worthy of special attention. We have employed the methodology proposed by Borjas (2003), which analyses individual-level data at the national level. Education-experience groups are first defined and each group is assigned an immigrant supply shock variable. By regressing the supply shock against various measures of labour market outcomes, it is possible to derive the elasticity of supply of immigrants.

The estimated supply elasticities suggest that the earnings of pre-existing workers increase by less than 1% for a 10% increase in the supply of immigrants. The size of these coefficients together with the large standard errors provides evidence for the hypothesis that immigration has little impact on earnings. As New Zealand operates a skilled-immigration system, it is worth restricting the analysis to the various levels of education. In particular, when we restrict the analysis to highly skilled workers (bachelor or higher degree), we continue to find no substantial change in the impact of immigration on the earnings or employment of pre-existing workers.

We extend the standard national-level approach to incorporate local government regions in the analysis. This is an interesting extension because it illustrates the geographic distribution of immigration and the effect of this distribution in each region. For New Zealand, this is important as a large proportion of immigrants reside in a particular region (the Auckland region). When groups are defined by region-education-experience, the results change. In fact, the estimates report negative effects on labour market outcomes. However, even though results are statistically significant, the size of the negative impact from immigration is still small—an approximately 1.5% reduction in earnings from a 10% rise in immigrant inflow.

It is common for firms to value experience acquired in the domestic market differently from experience acquired abroad. To take into account these different values placed on labour market experience, we define ‘effective experience’ for each worker. Depending on the type and level of experience of each worker, experience is rescaled to reflect estimated market value. However, human capital comprises multiple dimensions and it is not practical to rescale every dimension of skill. Instead, we assign individuals into various segments of the earnings distribution with the assumption that similarly skilled workers fall in the same region of the earnings distribution. Based on this skill framework, the estimates of elasticity of supply continue to be small. In summary, it seems to be the case that immigration in New Zealand causes unsubstantial changes to the economic outcomes of pre-existing workers.

The effects of immigration on wages and employment hours per worker reported in this chapter suggest that they are minor, but there is evidence that the effects tend towards the negative direction. Further analysis shows that effects for the sub-sample of native-born men remain insignificant, indicating that the effects observed reflect outcomes for earlier immigrants for whom recent immigrants are closer substitutes. These results fall between the findings of Borjas (2003), who finds significant negative effects, and those of Dustmann et al. (2005), who find no significant effects.

However, the picture is not complete. It would be useful to also evaluate the long-term adjustments to the factors of production due to immigration; account for potential changes in the productivity factor of the economy; and also create a framework that captures the potential benefits (and consequences) of immigration and the resulting spillover effects.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

However, Maré and Stillman (2009) do find that the intermediate skill group is worse off, but this is offset by positive effects on the better skilled group.

- 3.

The data sources are decennial Censuses from 1960 to 1990 and Current Population Surveys from 1998 to 2001.

- 4.

D’Amuri et al. (2010) find no effect on the native-born, but significant adverse effects from new immigration on the earnings of existing immigrants.

- 5.

D’Amuri et al. (2010) also estimate the elasticity of substitution between old immigrants and new immigrants; they find the degree of substitution to be almost perfect.

- 6.

Carrasco et al. (2008) use the Census for 1991 and 2001, data on work permits from 1993 to 1999, the labour force survey and the wage structure survey 2002.

- 7.

Also, a general comparison of weekly earnings and the hourly wage for the native-born in all four groups of education shows growth rates of at least 10% in real terms during the time period.

- 8.

In the form of a Confidentialised Unit Record File (CURF).

- 9.

1–5 years, 6–10 years, 11–15 years, 16–20 years, 21–25 years, 26–30 years, 31–35 years and 36–40 years of experience.

- 10.

Since we have 6 consecutive years of data, inflation plays a very minor role.

- 11.

The typical number of hours worked for a full-time worker is 40 h.

- 12.

This results in 25 occupation categories. The categories are then combined into nine-distinct one-digit occupation categories by Statistics New Zealand, as applied in our estimation of the Index of Congruence in this section.

- 13.

In this particular analysis, experience groups are defined by 10-year intervals rather than the 5-year intervals employed earlier. This is to reduce the number of cells with few observations due to further classifications by two-digit-level occupation categories.

- 14.

One concern may be that the effect on employment is imprecise since the sample includes both full-time and part-time workers. When we restrict the estimation to full-time workers only, the coefficients remain positive and small, suggesting that the initial results do not include imprecision from the inclusion of part-time workers.

- 15.

Interactions are between region and education; region and experience; region and year; education and experience; education and year; experience and year; region, education, and experience; region, education, and year; region, experience, and year; and education, experience, and year.

- 16.

Looking at the impact on weekly earnings in Auckland, a 10% rise in the number of immigrants reduces earnings for workers in Auckland by almost 2.5%.

- 17.

See Borjas (2003).

- 18.

The confidentialised NZIS does not identify the exact number of years since migration for each immigrant. Instead, the years since migration variable in the NZIS is reported in intervals. This is not appropriate for the estimation of Eq. (10.5). To overcome this problem, immigrants in each interval are randomly assigned (with a uniform distribution) to a ‘year since migration’ value within the range of that particular interval. Following Borjas (2003), we use this method rather than the midpoints of each interval, where the distribution of assigned years in New Zealand reflects that of the actual data, but smooths out the ends of the distribution.

References

Addison T, Worswick C (2002) The impact of immigration on the earnings of natives: evidence from Australian micro data. Econ Rec 78(1):68–78

Akresh IR (2006) Occupational mobility among legal immigrants to the United States. Int Migr Rev 40:854–885

Altonji J, Card D (1991) The effects of immigration on the labor market outcomes of less-skilled natives. In: Abowd JM, Freeman RB (eds) Immigration, trade and the labor market. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 201–234

Antecol H, Kuhn P, Trejo SJ (2006) Assimilation via prices or quantities? Sources of immigrant earnings growth in Australia, Canada, and the United States. J Human Resour 41(4):821–840

Aydemir A, Borjas J (2011) Attenuation bias in measuring the wage impact of immigration. J Labor Econ 29(1):69–113

Becker GS (1975) Human capital, 2nd edn. Columbia University Press, New York

Borjas GJ (2001) Does immigration grease the wheels of the labor market? Brook Pap Econ Act 1:69–119

Borjas GJ (2003) The labour demand curve is downwards sloping: re-examining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118(4):1335–1374

Borjas GJ (2004) Increasing the supply of labor through immigration: measuring the impact on native-born workers. Centre for Immigration Studies

Borjas GJ (2005) The labor-market impact of high-skill immigration. Am Econ Rev 95(2):56–60

Borjas GJ, Freeman RB, Katz L (1996) Searching for the effect of immigration on the labor market. Am Econ Rev 86(2):246–251

Borjas GJ, Grogger J, Hanson GH (2008) Imperfect substitution between immigrants and natives: a reappraisal. NBER Working Paper No. 13887, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Card D (1990) The impact of the mariel boatlift on the Miami labor market. Ind Labor Relat Rev 43(2):245–257

Card D (2001) Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local market impacts of higher immigration. J Labor Econ 19(1):22–64

Card D (2005) Is the new immigration really so bad? Econ J 115(507):F300–F323

Carrasco R, Jimeno JF, Ortega AC (2008) The effect of immigration on the labor market performance of native-born workers: some evidence for Spain. J Popul Econ 21(3):627–648

Chiswick BR (1978) The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. J Polit Econ 86(5):897–921

D’Amuri F, Ottaviano GI, Peri G (2010) The labor market impact of immigration in Western Germany in the 1990s. Eur Econ Rev 54(4):550–570

Docquier F, Ozden C, Peri G (2013) The labour market effects of immigration and emigration in OECD countries. Econ J 124(579):1106–1145

Duleep HO, Regets MC (2002) The elusive concept of immigrant quality: evidence from 1970–1990. IZA Discussion Paper No. 631, IZA Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn

Dustmann C, Fabbri F, Preston I (2005) The impact of immigration on the British labour market. Econ J 115(507):F324–F341

Dustmann C, Glitz A, Frattini T (2008) The labour market impact of immigration. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 24(3):477–494

Eden P, Fredriksson P, Åslund O (2003) Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants—evidence from a natural experiment. Q J Econ 118(1):329–357

Hu W (2000) Immigrant earnings assimilation: estimates from longitudinal data. Am Econ Rev 90(2):367–372

Jean S, Causa O, Jimenez M, Wanner I (2010) Migration and labour market outcomes in OECD countries. OECD J Econ Stud 2010(1):1–34

Kifle T (2009) The effect of immigration on the earnings of native-born workers: evidence from Australia. J Socioecon 38(2):350–356

Lalonde RJ, Topel RH (1991) Immigrants in the American labor market: quality, assimilation, and distributional effects. Am Econ Rev 81(2):297–302

Leem HN (2008) An analysis of impact of low-skilled immigration on labour market outcomes in New Zealand. Master’s Dissertation, University of Auckland, Department of Economics

Longhi S, Nijkamp P, Poot J (2010) Meta-analyses of labour market impacts of immigration: key conclusions and policy implications. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 28:819–833

Maani SA, Chen Y (2012) Effects of a high-skilled immigration policy and immigrant occupational attainment on domestic wages. Aust J Labour Econ 15(2):101–121

Maré DC, Stillman S (2009) The impact of immigration on the labour market outcomes of New Zealanders. Motu Working Paper 09-11, Motu Economic and Public Policy Research

Mincer J (1974) Schooling, experience, and earnings. Columbia University Press, New York

Mishra P (2007) Emigration and wages in source countries: evidence from Mexico. J Dev Econ 82(1):180–199

Okkerse L (2008) How to measure labour market effects of immigration: a review. J Econ Surv 22(1):1–30

Orrenius PM, Zavodny M (2007) Does immigration affect wages? A look at occupation-level evidence. J Labor Econ 14(5):757–773

Ottaviano G, Peri G (2012) Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(1):152–197

Tse MMH, Maani SA (2017) The impacts of immigration on earnings and employment: accounting for effective immigrant work experience. Aust J Labour Econ 20(1):291–317

Wang G, Maani SA (2014a) Immigrants’ location choices, and employment in New Zealand, New Zealand. Popul Rev 40:85–110

Wang G, Maani SA (2014b) Ethnic capital and self-employment: a spatially autoregressive network approach. IZA J Migration 3(18):1–24

Welch F (1979) Effects of cohort size on earnings: the baby boom babies’ financial bust. J Polit Econ 87(5):S65–S97

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Statistics New Zealand for the use of the confidentialised unit record file (CURF) data (Household Labour Force (HLFS)-Income Survey (NZIS), 2002–2007). Access to the data used in this study was provided by Statistics New Zealand under conditions designed to keep individual information secure in accordance with the requirements of the Statistics Act 1975. Statistics New Zealand facilitates a wide range of social and economic analyses that enhance the value of official statistics. The opinions presented in this chapter are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent an official view of Statistics New Zealand. We would also like to thank the volume editors and three anonymous referees for insightful comments. An earlier version of this chapter was published as Tse and Maani (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Maani, S.A., Tse, M.M.H. (2020). Effective Work Experience and Labour Market Impacts of New Zealand Immigration. In: Poot, J., Roskruge, M. (eds) Population Change and Impacts in Asia and the Pacific. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives, vol 30. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0230-4_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0230-4_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-0229-8

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-0230-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)