Abstract

In this review of research on gender and low fertility, I develop three main categories: (1) studies seeking to explain why fertility is low; (2) studies on the efficacy of fertility-related policies; and (3) critical feminist studies that analyze discourses surrounding low fertility and fertility-related policy. I provide examples of each to illustrate how researchers interested in fertility use the concept of gender and to what end. I suggest that by repeatedly asking why fertility is so low and examining possible factors that prevent people from having children, demographic studies often implicitly reinforce the notion that low fertility is undesirable. More critical work points us in different directions, revealing how pronatalist policies – and the discourses surrounding such policies – may have deleterious effects on gender equity. Finally, I discuss work that asks different questions, such as how demographic trends may contribute to shaping state policies and/or other gendered structures. I conclude that future research should analyze how demographic trends and patterns are both shaped by and also shape gender.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Feminist scholars have bemoaned a persistent lack of serious engagement with the concept of gender in demographic research (Greenhalgh 1995; Riley 1999)Footnote 1 but in the past decade and a half, demographers increasingly examine the role of gender in shaping fertility. This shift has occurred at a time when concern with overpopulation and high fertility—considered the crucial economic development, environmental and geopolitical issue in the 1960s and 1970s—has waned. Today ‘low fertility ’Footnote 2 in ‘developed’Footnote 3 countries is framed as a threat to welfare state regimes, cultural cohesion, economic strength, and/or geopolitical power (see Demeny 2003; Goldstone 2010; Oláh 2011). An important strand of research now asks to what extent gender equity (or lack thereof) shapes fertility and, if a strong connection exists, how that knowledge should shape policy. Should, for example, states encourage gender equity in hopes of increasing birth rates? In this chapter, I review work on gender equity and fertility and ultimately contend that by repeatedly asking why fertility is so low and examining what prevents people from having children (or/and what makes larger families possible), demographic studies often reinforce the notion that low fertility is undesirable.

The concepts researchers use and the questions they ask matter because their studies contribute to the social construction of social problems (including the ‘problem’ of low fertility) and suggest their potential solutions (e.g. greater gender equality and/or more births). Demographic studies may thus form the basis of government policies designed to alter existing childbearing patterns, as have been instituted in various parts of the world. By providing basic research on determinants of fertility, population projections, or effectiveness of policies, demographers and other social scientists contribute to discourse that influences governments’ efforts to study and shape national populations (see Williams 2010; Riley, Chap. 8, this volume).Footnote 4 For social theorist Michel Foucault, “the concept of population itself constitutes a technology of liberal statecraft” (McCann 2009: 144–5). Population policies of all types (including fertility and immigration policies) can be understood as a technology of power in the Foucauldian sense, as states seek to shape the cultural, ethnic, or religious composition of the people under their jurisdictions. In addition, government policy to influence fertility may reinforce or re-shape gender structures as, for example, when states provide low-cost child care to facilitate combining parenthood with paid work or discursively emphasize women’s role as mothers, including ‘mothers of the nation’ (see Rivkin-Fish 2010; Kanaaneh 2002; see also Krause, Chap. 5 this volume).

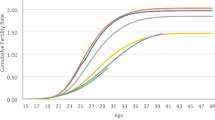

The Population Reference Bureau’s (2014) World Population Data Sheet reveals that in more developed countries fertility fell from 2.3 children per woman in 1970 to 1.6 in 2013; and currently many parts of the world—from southern and eastern Europe to East Asia—are experiencing ‘lowest-low’ fertility, that is, total fertility rates of less than 1.3 children per woman (Kohler et al. 2006 Suzuki 2008). This shift from low to very low fertility (and to higher rates of divorce, cohabitation, and non-marital births) is often referred to as the “second demographic transition” (Lesthaeghe 2010). It has become the task of many demographers to explain this transition and assess the extent to which fertility policies designed to raise birth rates achieve their intended goals. In the following sections, I review studies that use gender theory to examine fertility and assess fertility policies. Though much demographic research continues to use ‘gender’ “in a way that most social science fields now use the word ‘sex’ to describe differentials between males and females in such areas as education, work, and health” (Jill Williams 2010: 197), a small but growing body of work – the subject of this review – goes beyond an overly simple version of gender.Footnote 5

Work at the intersection of gender and fertility can be divided into three main categories: (1) studies seeking to explain why fertility is low; (2) research on the efficacy of fertility-related policies; and (3) critical feminist studies that analyze discourses surrounding low fertility and fertility-related policy. I provide examples of each to illustrate how researchers interested in low fertility use the concept of gender and to what end.

1 Explaining Why Fertility Is Low

Gender equity has come to be employed in analyses of fertility determinants in part because other models—mainly economic-based theories (e.g. Becker’s rational choice models, 1960, 1981)—have been unable to completely account for very low fertility . Economic theories typically use a rational choice lens, arguing that people engage in cost-benefit analysis when deciding whether to have children (see Becker 1960, 1981). Under this calculus, women might choose to work for pay rather than forgo income to stay home to raise children. In the 1960s and 1970s, economic models showed that women’s labor force participation was negatively correlated with fertility. In the 1980s, however, demographers found that women’s labor force participation in relatively affluent countries was correlated with higher fertility, a reversal of previous trends (Morgan 2003; Rindfuss et al. 2003; Suzuki 2008).

As existing frameworks could only partially account for low-low fertility , feminist critiques and frameworks slowly found their way into demographic theory. Riley and McCarthy (2003: 106) argue that to incorporate the complexities of gender we need to integrate the notion of “gender as a social construction and a recognition of the role of power in issues of gender and gender inequalities.” The gender equity approach (McDonald 2000, 2013) has provided a framework for a structural analysis by pointing to the institutional contexts of gender equality. Following Mason’s (1997) discussion of institutionalized gender systems, McDonald (2000) proposes that if relative gender equity exists in individual-oriented institutions—such as education and employment—but not in families, very low fertility may result as women bear the burden of paid employment and also housework and care duties. As Torr and Short (2004) note, McDonald’s theory resembles Hochschild and Machung’s (1989) concept of a ‘stalled revolution.’ In the first stage of this stalled gender revolution, when education and labor force opportunities open up for them, women share tasks in the public sphere; but men tend not to share work in the private sphere, putting pressure on families to limit the number of children they have. In the second, largely unrealized stage, men would contribute equally to household and care work and fertility would theoretically rise as women experience less strain from combining paid work with household duties (see Goldscheider et al. 2010). Though any sort of evolutionary, staged model can be problematic if it assumes a similar phenomenon will occur everywhere, the gender equity theory has been applied to numerous countries with very low fertility , especially – though not exclusively – European countries. Though few of these studies take an explicit political stance, the stakes are high. If greater gender equity does indeed contribute to higher fertility, more policy makers might support efforts aimed at promoting greater gender equity, including parental leave, child care, and equitable workplace policies.

Gender equity theory has been used especially to explain very low fertility . In a study of very low fertility in Korea, Suzuki (2008: 36) explains that “there is a cultural divide between moderately low fertility and lowest-low fertility. While all western and northern European countries and English-speaking countries have stayed at moderately low fertility, many countries in southern Europe, eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, and eastern Asia experienced lowest-low fertility.” Researchers have suggested that lowest-low fertility can be explained by strong ‘traditional’ familialism, in which mothers continue to be the main child care providers (see Suzuki 2008).Footnote 6

The theory that men’s lack of participation in child care results in lower fertility makes intuitive sense; but studies have not produced uniform results. For example, Puur et al. (2008) found that men with more egalitarian attitudes have higher fertility aspirations than men with traditional attitudes about gender while Westoff and Higgens (2009) found the opposite to be true.

A number of studies support the theory that gender equity is linked to fertility (see review in Aassve et al. 2015). In a comparison of Spain and Italy , two very low fertility countries , Arpino and Tavares (2013) found that when attitudes favor gender equity in the labor market but not in the home, fertility is lower than when attitudes favor gender equity in both realms. Miettinen et al. (2011) measured attitudes about gender equality in both domestic and public spheres in Finland with nine statements, such as “men are more committed to their work than women.” They found that for men, the relationship is U shaped ; traditional but also egalitarian attitudes raise men’s fertility intentions. For women, impact of gender attitudes is smaller and more ambiguous.

In another study of attitudes, Goldscheider et al. (2013), using longitudinal data from Sweden, measured attitudes about sharing housework and child care before people became parents and the actual sharing that occurred after the transition to parenthood. They found that, especially for women, an inconsistency between attitudes prior to having a child and actual sharing of household work that occurs once a child is present decreases the likelihood of having a second child. They explain that “it is inconsistency between ‘ideals’ and ‘reality’” that significantly delays continued childbearing (p. 1113).

Using data from five countries, Aassve et al. (2015) examined individuals’ attitudes about gender equality and the division of household labor to determine whether a mismatch between gender equity and gender ideology affects childbearing decisions. Aassve and colleagues found partial support for their hypothesis that consistency between gender attitudes and equality in sharing household tasks has a positive effect on fertility and assert that their study “brings further support to the argument that fertility increases when gender ideology is not traditional and the woman does not bear a disproportionate amount of the household work” (p. 854).

In a comparison of Italy and Spain, Cooke (2009) investigated whether differences in gender equity both inside and outside the family yield different fertility rates. Variables measuring gender equity outside the family included education; wife’s employment; wife’s earnings as a percentage of the total household income; and whether the wife is employed in the public sector. Measures for equity inside the family included the division of care between mothers and fathers; whether there’s a third adult in the household who might help with household or child care duties; and whether people pay for child care. Cooke found that the presence of a third person in the house increases chances of having a second child, as does paying for child care. Her results support the gender equity theory in that they “suggest that increases in women’s employment equity increase not only the degree of equity within the home, but also the beneficial effects of equity on fertility. These equity effects help to offset the negative relationship historically found between female employment and fertility” (p. 123).

Finally, Bernhard and Goldscheider (2006) studied factors affecting Swedish men’s and women’s views about the costs and benefits of having children, with a specific focus on views of men’s participation in housework and care work and men’s and women’s attitudes about the costs and benefits of becoming parents. They concluded that “even in a country as far into the Second Demographic transition as Sweden, negotiating shared parenthood is still sufficiently difficult that it depresses fertility, but now because of its impact on men” (p. 19). Noting that some studies have shown that couples are more likely to have second and third births when fathers are involved with child care, Goldsheider et al. (2010) stress the need for more research on men’s attitudes and fertility.

Some studies, however, have found limited or no support for gender equity theory . Examining how an unequal division of household labor shapes fertility in Italy , which has low-low fertility , and the Netherlands, where fertility is comparatively higher, Melinda Mills et al. (2008) found no clear link between asymmetrical division of household labor and lower fertility intentions. And in a study of Italian women’s fertility intentions and actual behavior, Rinesi et al. (2011) found that sharing domestic work did not affect fertility plans.

In their investigation of numerous Eastern and Western European countries Neyer et al. (2013) examined three aspects of gender equality—employment (the capacity to form and maintain a household), financial resources (the capabilities for agency), and family work (the gender division of household and care work)—and fertility intentions. They found no uniform effect of gender equality on childbearing intentions and instead note the importance of examining women’s and men’s fertility intentions separately, because “parenthood has different consequences for women than for men” (p. 255). They explain: “Compared to the general assumption in demography that the gap between gender equality in the employment sphere and gender inequality in the family sphere keeps fertility at low levels, our results reveal that the relationship between gender equality, employment, family work and fertility is much more complex (p. 267).

Goldscheider et al. (2010: 193) emphasize the importance of context, which “requires that we separate measures of male gender attitudes into those associated with the public sphere and those associated with the private sphere” and necessitates an historical orientation, including an understanding of the stages of the gender revolution. And as other feminist scholars (e.g. Riley and McCarthy 2003) have pointed out, it is important to understand how gender is constructed and understood in specific contexts. Rarely do quantitative data allow for nuanced investigations into such questions; but occasionally, researchers use a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods to study low fertility , which allows for a more complicated examination of gender systems.

Demographer Breinna Perelli-Harris (2005) examined fertility in Ukraine and found Ukraine’s experience to be somewhat different from most European countries in that, despite very low fertility (about 1.1 children per woman in 2001), childbearing is nearly universal and women still tend to have their first (and, typically, only) child at a fairly young age. Perelli-Harris used the Ukrainian Reproductive Health Survey (7129 women, aged 15–44) from 1999 and data collected from 22 focus groups in 2002 and 2003. While low fertility in Western Europe is often associated with value shifts away from extended families and toward careers, this has not been the case in Ukraine, where women tend to work but often do not opt for careers. In focus groups, “few women rated career or financial independence as more important than marriage and family. These comments” she explains, “reflect the paradox within Ukrainian society of, on the one hand, the drive for equality of the sexes within education and the workforce, and, on the other, a commitment to the preservation of traditional gender roles, based on a conviction that there are essential, psychological differences between men and women” (p. 64). Perelli-Harris concludes that the common explanations for low fertility in Western Europe, such as economic uncertainty and disjunction between higher level of gender equity in employment and education but lower levels within families, don’t fully explain how Ukraine has come to have low-low fertility.

Anthropologist Joana Mishtal (2009, 2012) investigated the case of Poland, which has one of the lowest fertility levels in the EU (1.27 children per woman in 2007). Stressing the importance of context, Mishtal suggests that the Second Demographic Transition theory may partially but not completely hold for Poland, where abortion and access to birth control have been limited and the role of the church remains very important. Using data derived from 55 qualitative interviews and a quantitative survey of 418 women aged 18–40 to find out what factors influence women’s fertility decision making, Mishtal (2009) shows that women are regularly discriminated against in the workplace; for example, it can be difficult to take maternity leave and some employers require women to pledge that they won’t get pregnant. The women Mishtal interviewed tended to be aware of a ‘demographic crisis’ but felt no compunction to do anything about it; instead they felt the state should enact policies to make it easier to have children. Mishtal (2009: 621) argues that “while northern European nations such as Sweden are refining their work-family reconciliation policies to address declining fertility, in the case of Poland there is a need for policies protecting women’s job security designed to redress fundamental gendered discrimination in employment before effective work-family reconciliation laws can be initiated.”

To summarize, this brief (and necessarily incomplete) review shows that research seeking to explain low fertility includes increasingly nuanced discussions of institutionalized gender structures and, occasionally (especially where qualitative data are brought to bear), how gender is socially constructed. Many studies also contain introductions and literature reviews that offer nuanced and complex discussions of gender. What typically remains unanswered, however, is why researchers study what shapes fertility in the first place. One reason to examine potential connections between gender equity and fertility—implicit (and sometimes explicitly stated) in the studies discussed here—is that low fertility is often considered undesirable for nations and thus, in order that the state might at some point intervene, or intervene more effectively, policy makers want to know what shapes people’s reproductive decision making. A second reason to study the intersection of gender and fertility might be so that states could institute policies not for nationalist goals but instead in order to help individuals achieve their own desired number of births (be that more or fewer births). By focusing on a possible gap between desired and achieved fertility, some researchers (e.g. Maher 2007) take this tack. It seems unlikely, though, that states would institute policies to help people achieve their desired fertility unless those individual desires meshed with state goals.

Because policy makers often consider low fertility to be undesirable, an increasing number of governments seek to raise or maintain fertility as birth rates drop to previously unrecorded levels. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2013: 6), the proportion of governments with policies to lower birth rates has hardly changed since 1996, while the proportion with policies to raise fertility increased from 14% to 27% between 1996 and 2013. In 2013, 54 countries had policies to raise fertility and 33 had policies to maintain current rates (compared to 27 and 19 respectively in 1996). As anthropologist Susan Greenhalgh (1996) has noted, demography has historically been dependent for funding on government entities and has always had a policy orientation. It is not surprising, then, that much emerging work on gender and fertility deals with the efficacy of policy.

In fact, a whole data gathering effort in Europe has been designed to contribute to knowledge about gender and fertility. In 2000 the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) launched the Generations and Gender Programme, the goal of which is to “provide data that can contribute to enhanced understanding of demographic and social developments and of the factors that influence these developments, with particular attention given to relationships between children and parents (generations) and those between partners (gender)” (UNECE 2015). In their explanation of the Generations and Gender Survey, which is a part of the larger Programme, Vikat et al. (2007: 391) explain: “By studying the relationships between parents and children and the relationships between partners, we can capture the determinants of demographic choices at the individual level, thereby achieving a better understanding of the causal mechanisms that underlie demographic change. This knowledge, in turn, can build the basis for devising policies that respond to the demographic changes and population development in Europe.”

2 Research on Pronatalist or/and Fertility-Related Policies

According to Lynn Prince Cooke (2009: 124), evidence “suggests that the more policy encourages greater equity in the division of paid and unpaid labour, the more gender equity enhances fertility.” In this section I present selected research on gender equity in the context of efforts to raise fertility. First, I provide examples of work that seeks to evaluate the effectiveness of fertility-related policies. Then, I discuss debates over the use of gender-equity polices to raise birth rates and provide an example of one such effort, the current gender-equality policy in Japan .

2.1 Evaluative Studies

In their introduction to a collection of papers evaluating whether policies can enhance fertility in European countries, Gauthier and Philipov (2008) explain that many policies that affect fertility are not explicitly pronatalist; instead, they are aimed at increasing gender equality or encouraging women’s labor force participation but have implications for fertility. Research is inconclusive as to the effects on fertility of specific financial incentives, such as baby bonuses, tax allowances, and other parental allowances. However, there is evidence that overall support for families does matter; and, in addition, Gauthier and Philipov (2008: 9) suggest that “what may also strongly matter for families … are the stability of this financial support and the status of the overall economy.” In reviewing work- and gender-related policies, Gauthier and Philipov note that though the European Union has set targets for child care provision and seeks to remove disincentives to female labor force participation, there remain large cross-national differences. High levels of gender equality in Nordic countries (as illustrated, for example, by fathers’ relatively high take-up rate of parental leave and fathers’ participation in child care) are correlated with relatively high fertility. But, Gauthier and Philipov ask, is gender equality a prerequisite of higher fertility? They note that “the higher-than-average level of fertility observed in France also co-exists without significant achievements with respect to gender equality. … Thus, while fertility, gender relations and policies may be related, their actual combination may reflect broader societal norms and institutions, thus preventing broader generalization across countries” (p. 13). As we have seen in the discussion of studies investigating the determinants of fertility, context matters. For example, low-low fertility occurred in some countries (including Germany, Italy , and many other European countries) in the context of postponement of childbearing and high levels of childlessness , while Ukraine achieved low-low fertility in the context of near universal childbearing at young ages.

Russia, with high mortality and low-low fertility rates , is staunchly pronatalist and numerous articles examine the efficacy of that country’s policies. Vladimir Putin stated in 2006 that population policy is the most urgent item on the state’s agenda (Avdeyeva 2011; Rivkin-Fish 2010). Among other things, in 2007, the state created a “maternity capital” entitlement in the form of a $10,000 voucher (250,000 rubles indexed to inflation) to mothers when their second or third child turns three and raised monthly allowances for families caring for children (Rivkin-Fish 2010). Olga Avdeyeva (2011: 362) explains that Putin “recognized the dependency and discrimination within the family that women suffer when they choose to have a second child and have to withdraw from the labor force for a long time.” However, reviewing and assessing Russia’s current policies using McDonald’s gender equity theory , Avdeyeva concludes that though Russia’s aggressively pronatal policies do address some economic issues related to childbearing they fail to fundamentally challenge longstanding gender hierarchies; they don’t meaningfully incorporate employers or fathers or male partners. Thus, she speculates that fertility will continue to remain very low. She also warns that “an adoption of pronatalist programs can be potentially dangerous, because they remove concerns about gender equality off the state agenda and push women to the private child-caring sphere” (p. 381). Avdeyeva concludes with a note of caution on the “usage of cash-for-baby programs as ineffective tools for changing fertility rates, on the one hand, and contributing to further institutionalization of gender inequalities both in the family and in the labor markets, on the other hand” (p. 381–82).

In contrast to Russia, Sweden is known for having ‘highest-low’ fertility and is famous for its relatively generous welfare state benefits and family policies. Raising fertility was one impetus for the original enactment of certain family policies in the 1930s (see King 2001), but in recent decades their aim has been to support women’s labor force participation and promote gender equality (Anderrson 2008). Sweden and the other Scandinavian countries are often cited as examples where levels of gender equity in families , as well as in education and workplaces, correlates with higher fertility. Anderrson (2008: 98) argues that in Sweden, relatively high fertility is related to the setup of the welfare state, specifically, a combination of “individual taxation, a flexible parental leave scheme based on income replacement and a system of high quality day care. Together they support the present dual bread-winner model of Sweden.”

Duvander et al. (2010) investigate the extent to which fathers’ and mothers’ use of parental leave impacts childbearing in Norway and Sweden, where family policies aim to facilitate the combination of paid work and childrearing and where fertility, compared to most of the rest of Europe, is fairly high (just over 1.9 children per woman in 2008). Parents may receive paid parental leave for about 1 year, and part of that leave is reserved for the father (both countries apportion some part of the parental leave specifically to fathers—Sweden 2 months and Norway 10 weeks—in hopes of encouraging their greater participation in child care). The authors find a positive association between fathers’ use of parental leave and childbearing propensities in both countries; however, the impact of mothers’ use of parental leave is a bit more complicated (mothers who stay home the longest after a second birth are the most likely to have a third child, and women who have more than two children tend to “lean towards concentrating on childrearing”(p. 55). While noting that their analysis cannot show causality, the authors conclude that, “the similarity of findings in Norway and Sweden makes the evidence stronger that increased paternal involvement in childrearing is positively related to continued family building” (p. 55).

Patricia Boling (2008) compares fertility in France and Japan , both of which have long histories of concern with low birth rates, influential national demographic research institutes, elite bureaucrats in policy making roles and pronatalist programs under both conservative and progressive governments. In the mid-2000s, France’s total fertility rate (TFR) was 1.98, while Japan’s was 1.29. What accounts for this difference? Boling argues that though French policies—including family allowances; maternity and parental leave; child care; early childhood education; and tax benefits—are more generous than Japanese programs , the differences in policy don’t completely explain differences in fertility. A crucial factor is work culture. Boling states (p. 320), “workers in Japan spend many more hours a week on both paid and unpaid work than they do in France. Japan’s culture of long work hours leaves ideal workers with little time to contribute to their families and households. Typically this means that women do all the household, childrearing, and care work with minimal involvement from their husbands. . . . Japan’s dual labor market expectations about the commitment of fulltime workers and the tendency to confine women, especially mothers, to low-paid part-time jobs are crucial to understanding this predicament” (see also Dales’ Chap. 19 on marriage in Japan, this volume).

Because gender equality—in the form of a more equal division of care work and household work and greater equality in paid employment and in education—has been associated with relatively higher fertility, policy makers and researchers debate whether and to what extent policy should encourage gender equity in the interest of raising birth rates.

2.2 Policies and Policy Debates

In 2011, the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research sponsored a debate in which researchers were asked to respond to the question, “should governments in Europe be more aggressive in pushing for gender equality to raise fertility?” The two ‘yes’ positions were written by Laurent Toulemon (researcher at France’s Institute for Demographic Studies—INED) and Livia Oláh (a demographer at Stockholm University).

Citing studies that show how gender equity —in the form of use of paternity leaves, education, and equal division of household work—is positively correlated with fertility, Oláh (2011) argues in favor of governments promoting gender equity in order to raise fertility. People in European countries, she contends, tend to want two children on average, and governments could help them achieve their desired fertility.

Toulemon’s (2011) ‘yes’ to governments pushing for gender equity in the name of fertility is much more tentative or qualified. Among other things, he claims, it is difficult to know whether fertility is really too low (and for whom? Individuals? Governments?) and whether low fertility merits government action. Toulemon does think that in some cases policies to raise fertility might be a good idea but questions whether demographers are the most qualified to answer this question. He argues that greater gender equality could raise fertility but that it is also “an objective per se” (p. 195).

On the ‘no’ side, Dimiter Philipov (a Bulgarian demographer who has worked at the Vienna Institute of Demography and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Germany) assumes that government policies would be focused on a ‘dual-earner/dual-carer’ model (2011: 201). Arguing that the idea that increases in gender equality lead to higher fertility is not based on sound research, he raises five objections to dual-earner/dual-carer model: (1) it doesn’t necessarily lead to fertility increase; (2) it will lead to imbalance of labor supply and demand; (3) policies will hit up against cultural norms pertaining to gender differences that they will not be able to overcome; (4) policies will hit up against innate gender differences they will not be able to overcome; and (5) there can’t be a unified approach due to country idiosyncrasies. Philipov does not oppose government intervention; rather, he opposes intervention that focuses on gender equality in the name of fertility. He states that “an efficient increase in fertility can be achieved when family policies are gender-neutral, and when gender equality policies are fertility-neutral” (p. 213).

Finally, Gerda Neyer (2011), political scientist and demographer at Stockholm University, argues ‘no’ for completely different reasons. She posits a threefold ‘no’: no to trying to raise fertility at all; no to the method, which is to push for population policies more aggressively; and no to the means (to use gender policies to promote fertility). Neyer takes issue with claims that position low fertility as problematic, explaining that first, such claims are ageist (as they tend to voice concern with population aging ) and second, that fears of low fertility and population decline are connected to Eurocentrism and a myth of ethnic homogeneity. In addition, she argues that claims that higher fertility will help the labor market are faulty: “future labor market and economic issues cannot be settled by raising fertility, since more (or fewer) children will not protect us from the need to restructure markets in the face of globalization, aging , technological advancement, or other economically relevant developments,” (p. 232) and she stresses that there is no way to know what the connection between economic development and fertility will be in the future. In terms of the effects of fertility on welfare states, Neyer explains that social security systems are vulnerable because of institutional design and the design of social policies, not just demographic changes.

Importantly, Neyer points out possible detrimental consequences for gender equality if it is linked to fertility. For example, gender equality policies could become dependent on people’s reproductive behavior. In addition, policies situated in a fertility framework “tend to essentialize heterosexuality and to regard women (and men) as a homogenous group” (p. 243). Also, using gender equality to raise fertility could narrow how gender equality is conceptualized (for example, what about issues that have nothing to do with fertility, such as inequalities in income, career opportunities, and political representation?).

While European demographers have debated whether and how governments should take action in terms of gender equity and fertility , in 1999, the Japanese government enacted the Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society in hopes that greater gender equality would lead to higher birth rates. The preamble to the law reads “to respond to the rapid changes occurring in Japan’s socio-economic situation, such as the trend toward fewer children, the aging of the population, and the maturation of domestic activities, it has become a matter of urgent importance to realize a gender-equal society” (quoted in Huen 2007: 369).

According to Huen (2007), Japan’s Basic Law and other, subsequent policies have not been particularly effective in dismantling a gendered division of labor in which women are expected to do a lion’s share of care work and are often discriminated against in the workplace. In addition, Huen (2007: 377) suggests that “[s]ince the pursuit of gender equality is a means to boost the birth rate, when there is a contradiction between these two goals, the former will be conceded.”

In 2005, the Japanese government created a Cabinet Office to deal with low fertility , led by a new ‘Minister of State for Declining Birthrate and Gender Equity .’ Annette Schad-Seifert (2006: 5) writes that this “is an indication of the rising awareness that the drop in the birthrate is closely related to radical changes in the country’s social fabric and the fact that equal opportunities for men and women to combine family care work and employment are still in demand.” Schad-Seifert explains that the government is taking steps to address Japan’s ‘workaholic’, male-breadwinner culture. For example, one government program rewards companies where a certain number of fathers take child-care leave. And while extending the availability of child care and providing family allowances may not in fact raise fertility (Boling 2008), and Schad-Seifert (2006: 26) suggests that the work of the Specialist Committee on the Declining Birthrate and Gender Equality reflects “the fact that the falling birthrate is not for the most part induced by a change in the minds of women but is due to structural factors that are influencing individual decisions in both sexes.”

To summarize, research showing possible connections between greater gender equity and higher fertility has led to (1) studies intended to ascertain the extent to which policies promoting gender equity shape fertility; (2) debates over whether policy makers interested in raising fertility should do so via policies designed to increase gender-equity; and (3) investigations into how some countries have sought to use gender equity ideals in hopes of raising birth rates. I noted above that research examining whether greater gender equity is associated with higher fertility may be contributing to a discourse that positions low fertility as a problem and as an arena appropriate for government intervention. Similarly, those who study connections between fertility levels and government policies that promote gender equity may be sending a message that raising fertility is desirable and that increasing the national birth rate is thus a reason (or even the reason) to promote gender equity—a problematic stance (see Neyer 2011).

In the final section of this review, I provide examples of work that takes a more critical approach by investigating discourses surrounding fertility policies. This type of work is fairly uncommon but is important because it can reveal a complex and nuanced picture of the various ideological perspectives on fertility policies in specific locations and can thus provide insight into both how such policies come to be enacted as well as public responses.

3 Discourses Surrounding Gender and Low Fertility

Work, mostly by anthropologists, examining discourse uncovers meaning and motivations surrounding fertility-related policies that may not be explicitly stated by policy makers. Rivkin-Fish (2010) shows how discourses surrounding demographic policies in Russia reaffirm existing ideas and meanings about fertility and gender and also reformulate or add new meanings that may ultimately influence policy. She contends that Vladimir Putin has linked raising women’s status with fertility; in an attempt to both improve women’s status and increase fertility, he instituted payments (‘maternity capital’) to mothers who have two or three children. Concern with demographic trends, contends Rivkin-Fish, has re-legitimized claims for government assistance that neoliberal ideology had called into question. This might be considered to be a positive development; but, at the same time, the state has also (presumably with fertility trends in mind) placed new restrictions on second trimester abortions that limit access. She explains that, in this scenario, “reproductive politics becomes a means of demonstrating concern for national well-being while obscuring the instrumentalization of women’s bodies and lives” (2010: 724). The example of fertility politics in Putin’s Russia—where policy makers have simultaneously attempted to increase gender equity by providing financial assistance to mothers but restricted access to abortion—partially illustrates Neyer’s (2011) argument that gender equality, if invoked mainly as a way to raise fertility, may be very narrowly conceptualized.Footnote 7

Krause and Marchesi (2007) investigate a paradox in Italian policy whereby, in the 2000s, a new, pronatalist baby bonus was introduced around the same time as an ‘anti-natal’ law restricting assisted reproduction. Explaining that ‘modernity’ is an ongoing project in Italy and that Italians don’t always feel completely sure that their nation is modern enough, these authors suggest that fertility policies allow the state to “redefine its boundaries, situate itself in relation to modernity, and express its preferred moral orientations” (p. 351L). Low fertility used to be a sign of modernity but now, because it is linked with ‘traditional’ family forms, low-low fertility is ‘unmodern.’ Meanwhile, discourse against the assisted reproduction law, which barred single women and same-sex couples from access to infertility treatments, focused on the law as ‘unmodern.’

Rivkin-Fish (2010) and Krause and Marchesi (2007) reveal a complicated and contradictory set of issues surrounding fertility policies . Such work can reveal how concern with low fertility can lead to seemingly progressive policies to extend state assistance to citizens but may be complemented by conservative efforts to restrict reproductive choices. They also show how demographic trends become a site for debates over the character of the nation.

4 Discussion and Conclusion

This review of the literature on gender equity and low fertility has focused mainly on work that investigates either why fertility is low or various aspects of fertility-related policy. I also provided examples of work that examines discourses surrounding the question of low fertility and fertility-related policies. The examples provide evidence that researchers are using fairly nuanced concepts of gender. Jill Williams (2010: 204), however, suggests that, “feminist-demographic research on gender must be emancipatory, must have a theoretical basis, must acknowledge its political underpinnings, and must incorporate reflexivity about the influence of social position on knowledge produced.” Demographers and other social scientists interested in explaining low fertility increasingly use a gender equity lens . They often construct nuanced discussions of gender that emphasize the importance of institutions and context. But the extent to which much of this research is ‘feminist’ as defined by Williams is debatable. Researchers who fail to critique the dominant frame that positions low fertility as a problem contribute to a set of discourses about state and nation that may be exclusionary. Low-low fertility calls into question the concept of an ethnically homogeneous nation state. In some countries (such as the United States), ‘the nation ’ has been constructed primarily as a political entity; in others, ethnic or cultural heritage has served as the basis for the construction of the nation (see King 2002). Especially in countries where the national story speaks of an ethnic or cultural tradition, immigration threatens that national story and low-low fertility in the absence of immigration means a possible end to the story. The unraveling of that specific construction of nation has implications for gender as well, as in those national stories, women tend to be constructed as the mothers of the national family, whose primary task is reproducing the nation (Kanaaneh 2002).

Gender equity theory has transformed demographic research on fertility; research now increasingly investigates how gendered-social institutions impact childbearing patterns. By continuing to ask the same question—“What causes fertility rates to be low (or to be high)?”—demographers contribute to a discourse that positions fertility rates as problematic and therefore potentially something to be addressed by policy makers (see also Krause, Chap. 5 this volume). Feminist scholars might (and do) take varying positions on whether, and to what extent, gender equity and fertility should be linked in discourse and policy; what is important is that researchers make the policy implications and their own political positions explicit. While some researchers (e.g. Neyer 2011) critique discourses that frame low fertility as undesirable, many implicitly or explicitly contribute to a discourse that sees low fertility as something to alter or shape.

In the final analysis, demographic research is about populations, making it necessarily mostly macro-level and quantitative. Though qualitative studies can illuminate the social construction of gender and reveal contextual specificities, demographic work typically seeks to show large-scale trends and patterns and can’t do what ethnographic work can do. However, demographic researchers can, and sometimes do, refer to qualitative studies to explain historical and cultural context (see for ex., Cooke 2009). Much of the research on gender and low fertility fails, however, to acknowledge potential political underpinnings. Why study the causes of low fertility if not to speak to possible government actions? This question seems to be elided in most studies. There are at least two very different positions one can take, for example, vis-à-vis the gender equity theory . One could argue, from a feminist perspective, for policies that promote gender equity and also, presumably, raise fertility (as in the 2011 Max Planck-sponsored debate discussed above) or, from a different feminist perspective, argue against such an approach (e.g. Neyer 2011). Though discussed in the Max Planck-sponsored debate, such positions are rarely made explicit in research articles. Because the question of what allows low fertility to occur or persist is so implicitly connected to a possible state agenda to shape populations, I suggest that researchers address different sociological questions about demographic changes.

4.1 Alternate Questions to Guide Research

Work that investigates other aspects of gender and fertility is less common and more of it is needed. For example, some research examines how gender and demography can help explain welfare state restructuring. Peng (2002) examines how gender relations and demographic trends have contributed to the shaping of family policy in Japan in the 1990s. She shows how, even in a neoliberal climate, the Japanese state expanded in areas such as public child care, parental and family leave, and other support services for workers with family responsibilities. Henniger et al. (2008) ask whether demographic trends contribute to gender equality in Germany, as new policies have sought to facilitate the combination of labor force participation and motherhood. Peng’s and Henniger et al.’s studies concern themselves with demographic trends, but instead of asking what shapes fertility they ask how demographic trends shape policy. Such research adds to our understanding of how welfare states evolve and what types of issues prompt policy makers to create specific programs.

Another question a few researchers are beginning to tackle is whether and how demographic trends, especially fertility trends, affect gender structures. In her piece on gender and demographic change published in 1997, Karen Mason (1997: 174) suggested that “there is reason to think that the demographic transition may serve as a precondition for the ‘gender transition’ in many parts of the world.” Members of the Fertility and Empowerment Network, part of the International Center for Research on Women, investigate how declines in birth rates impact gender structures in middle- and low-income countries. Two recent articles examine the effects of low fertility on gender structures. Keera Allendorf (2012), studies how fertility decline may alter the relative value of sons and daughters in families in an Indian village . Anju Malhotra (2012) asks more generally how fertility declines may shape gender relations. These examples show how researchers flip the main questions that demographic- and demographic-policy research typically pose. Rather than ask what causes low fertility or whether fertility-related policies have an effect on birth rates, they ask how changing fertility trends affect states, families, and/or gender structures. Such work illuminates gender and social change, and more research along these lines would add to scholars’ understanding of how gender structures evolve and transform.

Finally, this review focused on ‘low’ fertility in ‘developed’ countries and thus leaves unanswered the question of how gender is conceptualized in research on fertility in less-affluent countries. Studies of fertility in ‘developed’ versus ‘less developed’ countries use different lenses and ask different questions. Funding streams come from different governmental agencies and/or organizations and data availability varies significantly. Research specifically examining such differences would be instructive; it might illuminate whether and how context matters to how gender is framed. Is gender conceptualized in a more complex and multi-dimensional way in ‘more developed’ than in ‘less developed’ areas? Or have researchers examining fertility in the Global South, despite possible data limitations, managed to study gender in ways that go beyond ‘women’s status’?

Because gender structures shape fertility and because an increasing number of researchers are interested in exploring gender equality, it is likely that research linking gender and fertility will continue to evolve. Scholars will debate the extent to which greater gender equity leads to higher birth rates; and scholars and policy makers will likely continue to debate whether policies to promote gender equity ought to be instituted in the interest of raising fertility. Ideally, such researchers, possibly inspired by feminist authors, will think and write explicitly about the political implications of their research. Feminist activists, meanwhile, might draw on all types of emerging research linking gender structure and fertility to craft future political agendas.

Notes

- 1.

Gender is typically defined as the socially constructed set of rules and norms attached to the biologically-based (though also socially constructed) categories of sex and as a social structure that dictates behavior and allows for an unequal distribution of power and resources.

- 2.

Throughout this paper I will use the term ‘low fertility’ while recognizing that the term is problematic in that ‘low’ is inherently comparative and might imply ‘too low.’ Researchers typically use ‘low fertility’ to mean total fertility rates that are well below the ‘replacement level’ of 2.1 children per woman.

- 3.

I prefer ‘more or less affluent’ to ‘more or less developed’, as ‘developed’ implies superiority. However, much of the literature continues to use ‘more or less developed’, so I reluctantly use those terms when discussing such work.

- 4.

While any type of social science research may have policy implications, the connection between research and policy is particularly close in the field of demography. Many U.S. demographers in the post WWII era were caught up in the ‘overpopulation’ discourse, advocating family planning in ‘less developed’ countries (see Greenhalgh 1996); and French demographers and policy makers have historically been concerned with documenting and addressing low fertility (see Le Bras 1993).

- 5.

Note that almost all work on fertility implicitly addresses gender. To start with, fertility is measured in number of children per woman. Issues such as who takes care of children, whether women work in the paid labor force, women’s levels of education and many more gender-specific variables matter to fertility and have routinely been examined. However, though they used these variables, researchers typically did not address gender systems – in the sense of institutional and cultural structures or in terms of power – until recently (see Mason 1997).

- 6.

Suzuki (2008) argues that most countries are more conservative than northern and western Europe and the English-speaking countries in terms of the role of women and the commitment to marriage. Thus, Suzuki foresees lowest-low fertility spreading to places like South America.

- 7.

Interestingly, Rivkin-Fish (2010) also finds that reactions to government policy included a set of critiques of pronatalist programs that saw the ‘problem’ of low fertility as one of masculinity. According to some commentators, men have been emasculated by the state and economic situation such that they are no longer able to provide for families. Rivkin-Fish notes that such ideas contrast sharply with research arguing that increased gender equity supports higher fertility levels. She explains (2010: 721) that Russian critiques, by contrast, envision empowering men with renewed authority.”

References

Aassve, A., Fuochi, G., Mencarini, L., & Mendola, D. (2015). What is your couple type? Gender ideology, house-work sharing and babies. Demographic Research, 32(30), 835–858.

Allendorf, K. (2012). Like daughter, like son? Fertility decline and the transformation of gender systems in the family. Demographic Research, 27(16), 429–454.

Andersson, G. (2008). A review of policies and practices related to the ‘highest-low fertility of Sweden. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 6, 89–102.

Arpino, B., & Tavares, L. P. (2013). Fertility and values in Italy and Spain: A look at regional differences within the European context. Population Review, 52(1), 62–86.

Avdeyeva, O. A. (2011). Policy experiment in Russia: Cash-for-babies and fertility change. Social Politics, 8(3), 361–386.

Becker, G. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In G. S. Becker (Ed.), Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 209–231). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bernhardt, E., & Goldscheider, F. (2006). Gender equality, parent attitudes, and first births in Sweden. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 4, 19–39.

Boling, P. (2008). Demography, culture, and policy: Understanding Japan’s low fertility. Population and Development Review, 34(2), 307–326.

Cooke, L. P. (2009). Gender equity and fertility in Italy and Spain. Journal of Social Policy, 38(1), 123–140.

Demeny, P. (2003). Population policy dilemmas in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Population and Development Review, 29(1), 1–28.

Duvander, A., Lappegård, T., & Andersson, G. (2010). Family policy and fertility: Fathers’ and mothers’ use of parental leave and continued childbearing in Norway and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(1), 45–57.

Gauthier, A. H., & Philipov, D. (2008). Can policies enhance fertility in Europe? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 6, 1–16.

Goldscheider, F., Oláh, L. S., & Puur, A. (2010). Reconciling studies of men’s gender attitudes and fertility: Response to Westoff and Higgens. Demographic Research, 22(8), 189–198.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Branden, M. (2013). Domestic gender equality and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 29(40), 1097–1126.

Goldstone, J. A. (2010). The new population bomb: Four mega-trends that will change the world. Foreign Affairs, 89(1), 31–43.

Greenhalgh, S. (1995). Situating fertility. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Greenhalgh, S. (1996). The social construction of population science: An intellectual, institutional, and political history of twentieth-century demography. Comparative Studies in Science and History, 38(1), 26–66.

Henninger, A., Wimbauer, C., & Dombrowski, R. (2008). Demography as a push toward gender equality? Current reforms of German family policy. Social Politics, 15(3), 287–314.

Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (1989). The second shift. New York: Viking.

Huen, Y. W. P. (2007). Policy response to declining birth rate in Japan: Formation of a ‘gender-equal’ society. East Asia, 24(4), 365–379.

Kanaaneh, R. A. (2002). Birthing the nation: Strategies of Palestinian women in Israel. Berkeley: University of California Press.

King, L. (2001). From pronatalism to social welfare? Extending family allowances to minority populations in France and Israel. European Journal of Population, 17(4), 305–322.

King, L. (2002). Demographic trends, pronatalism and nationalist ideologies in the late twentieth century. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25(3), 367–389.

Kohler, H. P., Billari, F. C., & Ortega, J. A. (2006). Low fertility in Europe: Causes, implications and policy options. In F. R. Harris (Ed.), The baby bust: Who will do the work? Who will pay the taxes? (pp. 48–109). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Krause, E. L., & Marchesi, M. (2007). Fertility politics as ‘social viagra’: Reproducing boundaries, social cohesion, and modernity in Italy. American Anthropologist, 109(2), 350–362.

Le Bras, H. (1993). Marianne et les lapins: l’obsession démographique. Paris: Hachette.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Report 10–696, Population Studies Center, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

Maher, J. M. (2007). The fertile fields of policy? Examining fertility decision-making and policy settings. Social Policy and Society, 7(2), 159–172.

Malhotra, A. (2012). Remobilizing the gender and fertility connection: the case for examining the impact of fertility control and fertility declines on gender equality. International Center for Research on Women Fertility and Empowerment Work Paper Series, 001-2012-ICRW-FE (pp. 1–38).

Mason, K. O. (1997). Gender and demographic change: What do we know? In G. W. Jones, R. M. Douglas, J. C. Caldwell, & R. M. D’Souza (Eds.), The continuing demographic transition (pp. 158–182). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McCann, C. R. (2009). Malthusian men and demographic transitions: A case study of hegemonic masculinity in mid-twentieth-century population theory. Frontiers, 30(1), 142–171.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 26(3), 427–439.

McDonald, P. (2013). Societal foundations for explaining low fertility: Gender equity. Demographic Research, 28, 981–994.

Miettinen, A., Basten, S., & Rotkirch, A. (2011). Gender equality and fertility intentions revisited: Evidence from Finland. Demographic Research, 24(20), 469–496.

Mills, M., Mencarini, L., Tanturri, M. L., & Begall, K. (2008). Gender equity and fertility intentions in Italy and the Netherlands. Demographic Research, 18(1), 1–26.

Mishtal, J. (2009). Understanding low fertility in Poland: Demographic consequences of gendered discrimination in employment and postsocialist neoliberal restructuring. Demographic Research, 21(20), 599–626.

Mishtal, J. (2012). Irrational non-reproduction? The ‘dying nation’ and the postsocialist logics of declining motherhood in Poland. Anthropology & Medicine, 19(2), 153–169.

Morgan, P. S. (2003). Is low fertility a twenty-first century demographic crisis? Demography, 40(4), 589–603.

Neyer, G. (2011). Should governments in Europe be more aggressive in pushing for gender equality to raise fertility? The second ‘NO.’. Demographic Research, 24, 225–250.

Neyer, G., Lappegård, T., & Vignoli, D. (2013). Gender equality and fertility: Which equality matters? European Journal of Population, 29, 245–272.

Oláh, L. S. (2011). Should governments in Europe be more aggressive in pushing for gender equality to raise fertility? The second ‘YES.’. Demographic Research, 24(9), 217–224.

Peng, I. (2002). Social care in crisis: Gender, demography, and welfare state restructuring in Japan. Social Politics, 9(3), 411–443.

Perelli-Harris, B. (2005). The path to lowest-low fertility in the Ukraine. Population Studies, 59(1), 55–70.

Philipov, D. (2011). Should governments in Europe be more aggressive in pushing for gender equality to raise fertility? The first ‘no.’. Demographic Research, 24(8), 201–216.

Population Reference Bureau. (2014). World population data sheet. http://www.prb.org/Publications/Datasheets/2014/2014-world-population-data-sheet/data-sheet.aspx. Accessed Nov 2017.

Puur, A., Oláh, L. S., Tazi-Preve, M. I., & Dorbritz, J. (2008). Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19(56), 1883–1912.

Riley, N. E. (1999). Challenging demography: Contributions from feminist theory. Sociological Forum, 14(3), 369–397.

Riley, N. E., & McCarthy, J. (2003). Demography in the age of the postmodern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rindfuss, R., Guzzo, K. B., & Morgan, S. P. (2003). The changing institutional context of low fertility. Population Research and Policy Review, 22, 411–438.

Rinesi, F., Pinnelli, A., Prati, S., Castagnaro, C., & Iaccarino, C. (2011). The transition to second child in Italy: Expectations and realization. Population, 66(2), 391–406.

Rivkin-Fish, M. (2010). Pronatalism, gender politics, and the renewal of family support in Russia: Toward a feminist anthropology of ‘maternity capital’. Slavic Review, 69(3), 701–724.

Schad-Seifert, A. (2006). Coping with low fertility? Japan’s government measures for a gender equal society. German Institute for Japanese Studies Working Paper 06/4.

Suzuki, T. (2008). Korea’s strong familism and lowest-low fertility. International Journal of Japanese Sociology, 17, 30–41.

Torr, B. M., & Short, S. E. (2004). Second births and the second shift: A research note on gender equity and fertility. Population and Development Review, 30(1), 109–130.

Toulemon, L. (2011). Should governments in Europe be more aggressive in pushing for gender equality to raise fertility? The first ‘YES’. Demographic Research, 24(7), 179–200.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2013). World population policies 2013. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Gender and Generations Programme (2015). http://www.unece.org/population/areas-of-work/generations-and-gender/pauggpwelcome/populationggp/about-ggp.html. Accessed July 2015.

Vikat, A., Spéder, Z., Beets, G., Billari, F. C., Bühler, C., Désesquelles, A., Fokkema, T., Hoem, J. M., MacDonald, A., Neyer, G., Pailhé, A., Pinnelli, A., & Solaz, A. (2007). Generations and gender survey (GGS): Towards a better understanding of relationships and processes in the life course. Demographic Research, 17(14), 389–440.

Westoff, C. F., & Higgins, J. (2009). Relationships between men’s gender attitudes and fertility: Response to purr et al.’s ‘Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 21(3), 65–74.

Williams, J. R. (2010). Doing feminist-demography. Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(3), 197–210.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Science+Business Media B.V., part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

King, L. (2018). Gender in the Investigation and Politics of ‘Low’ Fertility. In: Riley, N., Brunson, J. (eds) International Handbook on Gender and Demographic Processes. International Handbooks of Population, vol 8. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1290-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1290-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-024-1288-8

Online ISBN: 978-94-024-1290-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)