Abstract

Once considered the weak link in China’s education, early childhood education has seen unprecedented development in recent years. The rapid development of China’s economy and the implementation of social and economic reforms have been accompanied by swift development of the preschool education sector. The growth of preschool education has also posed some challenges and difficulties. It has been necessary to ensure the quality of the preschool education against the background of rapid expansion and to meet the needs of socially disadvantaged rural and migrant children. This chapter reviews the development of early childhood education in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from a historical perspective and discusses strategies that have been implemented to overcome challenges posed by reforms to the preschool sector. Since 2010, the State has clearly taken more responsibility for preschool education. This is reflected in the recently issued guidelines and legislation and increased funding for the sector. The proper implementation of these initiatives will ensure that China will have a high-quality and effective system of preschool education.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Once considered the weak link in China’s education, early childhood education (ECE) has seen unprecedented development in recent years. The rapid development of China’s economy and the implementation of social and economic reforms have been accompanied by swift development of the preschool education sector. There have been notable increases in preschool participation, with enrolment rates in kindergartens increasing from less than 30 % in 1991 to over 70 % in 2014 (Ministry of Education, 2015a). The growth of preschool education has also posed some challenges and difficulties. It has been necessary to ensure the quality of the preschool education against the background of rapid expansion and to meet the needs of socially disadvantaged rural and migrant children. This chapter reviews the development of early childhood education in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from a historical perspective and discusses strategies that have been implemented to overcome challenges posed by reforms to the preschool sector. Since 2010, the State has clearly taken more responsibility for preschool education. This is reflected in the recently issued guidelines and legislation and increased funding for the sector. The proper implementation of these initiatives will ensure that China will have a high-quality and effective system of preschool education.

The Contemporary State of ECE in China

There are three main types of early childhood services in the PRC, including nurseries , kindergartens, and pre-primary classes . Nurseries provide care for children from birth to 3 years of age; kindergartens provide care and education to children between 3 and 6 or 7 years of age; and pre-primary classes cater to the needs of children from 5 to 6 or 7 years of age. Pre-primary classes are usually located in primary schools in rural areas.

Before turning to a historical review of early childhood education in China, it is important to emphasize that China currently operates the world’s largest preschool education system. In 2014, 40.51 million children ranging in age from 3 to 6 years were enrolled in 0.21 million kindergartens and were supported by 2.08 million teachers (Ministry of Education, 2015a). In 2014, 66.36 % of the kindergartens were privately owned (Ministry of Education, 2015b).

Preschool facilities in China can be generally divided into five categories based on their funding and management arrangements.Footnote 1,Footnote 2

-

1.

Category 1 consists of public kindergartens that are directly administered and fully funded by provincial and municipal education departments. Various levels of educational authorities manage these kindergartens. Their teachers are permanent staff and receive the same compensation and benefits as primary and secondary school teachers .

-

2.

Category 2 comprises public kindergartens that are fully funded and managed by state-owned enterprises or the Army. The teachers and parents of children attending these kindergartens are employees of these state-owned organizations. These kindergartens are not fully funded by the government but receive funding support for teachers’ salaries and for construction fees, from the budget of these (semi-)governmental organizations. Teachers in these kindergartens are treated as staff and get the same compensation as other employees in these (semi-)governmental agencies and state-owned enterprises.

-

3.

Category 3 includes public kindergartens that are under the jurisdiction of District Education Offices and receive partial financial support from the municipal government. The rest of the funding comes from the Bureau of Civil Affairs or other sources.

-

4.

Category 4 includes private kindergartens that are set up by individuals. Their funding mostly comes from parents. Teachers’ pay is decided by the owner of the kindergarten.

-

5.

Category 5 refers to some private kindergartens that have received financial support from the government in recent years as they are deemed as providing a service for the community. The tuition fees charged by these kindergartens are regulated by the government to ensure that low- and middle-income families can afford to pay for kindergarten education.

In addition, there are kindergarten programs in international schools which are mainly in major urban cities. These programs typically cater for international students, overseas Chinese who are working in China, and upper-middle class families.

The Development of Early Childhood Education in China

China’s education system has been subject to reform and change throughout history. An understanding of the development of preschool education is necessary to gain an understanding of current-day challenges. The roots of publicly funded preschool education in western countries and in China are different. In western countries, large numbers of young women joined the workforce after the Industrial Revolution that took place in the middle of the eighteenth century. Since women were engaged in paid employment, there was a need for child-minding services, and out-of-home early childhood care and education services were provided for the first time. Initially these services were provided by charitable organizations, but with time, governments all over the world have taken more responsibility in providing publicly funded preschool education (Lascarides & Hinitz, 2011).

On the other hand, ECE in China emerged for different reasons. It was not a response to women joining the workforce. Instead, it was a result of the political reform. The Qing government in Wuchang, Hubei Province, set up the first kindergarten, thereby marking the beginning of public preschool education in China (Zhu & Wang, 2005). After that, kindergartens established by the government and individuals started to appear in major cities. These early kindergartens primarily catered for children from wealthy families. Hence, in China, government-funded preschool education was first provided to privileged sectors of society, and it was only later that preschool education was available to children from working-class families or the “masses.” This was the reverse of the Western approach where preschool education was first provided to working-class families and then to more socially advantaged families.

The May 4 Movement in 1919, which is seen as the event that led to the founding of the Chinese Communist Party, marked the beginning of a new political era in China. It was felt that China’s problems could be alleviated by “two doctors” – doctor democracy and doctor science. The ideas associated with this “New Culture Movement” included the emancipation of women and exerted a strong impact on the development of preschool education in China . There were concerns that preschool education was a luxury, for the more advantaged members of society, and based on foreign ideas. Hence, scholars such as Tao Xingzhi, Chen Heqin, and Zhang Xuemen promoted the notion of establishing kindergartens that were accessible to working-class families, that had “Chinese” characteristics, and that were located near factories and in rural areas (Tang & Zhong, 1993; Zhu, 2008). Rural kindergartens and kindergartens for children from working-class families were thus established. However, in 1949, there were only 1300 kindergartens serving 130,000 children in China (Compilation Group of the History of Preschool Education in China, 1989; Tang & Zhong, 1993).

Development of ECE in China (1949–1978)

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, an increasing number of women joined the workforce. Early childhood care and education services were necessary to allow these women to engage in paid employment (Zhu & Wang, 2005). Hence, kindergartens were established in 1952 to meet both educational and social welfare objectives. They were developed to promote all-round development and education of young children and to provide childcare services. This enabled parents to engage in farming, manufacturing, and other forms of work and study, knowing that their children were getting quality out-of-home care and education.

A number of significant guidelines and/or laws have been developed and implemented in order to promote early childhood education since 1949. These, as well as major international treaties ratified by the PRC, are shown in Table 4.1 below.

The Decision to Change the Education System (Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government, 1951) was a particularly important document for preschool education in China. This document acknowledged, for the first time, that preschool education was a major component of the PRC’s education system . Official documents issued after 1951 recognized preschool education as the first component of the education system that preceded primary, secondary, and higher education, respectively.

As a result of the Decision, numerous factories, mines, enterprises, government offices, and schools set up childcare facilities for their employees. Childcare was considered a staff amenity that met a social welfare objective. As noted above, these “educare” services allowed working parents to focus on their jobs. Hence, regardless of whether a parent was a soldier fighting at the front line, or a factory worker, he/she could focus on his/her job with the knowledge that his/her child was being cared for in a safe and nurturing environment (Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government, 1951). In addition, residential early childhood facilities referred to as “boarding nurseries ” and “boarding kindergartens” were established by the local government, for children whose parents were soldiers or who were orphans. Further, in rural areas, mothers’ groups were established, and mothers took turns to take care of groups of children Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government, 1951).

With a large population, vast territory and a relatively backward economy , there was clearly a large need for preschool education. During the three decades from 1949 to 1978, the number of kindergartens in the country increased from 1300 to over 160,000, and the preschool enrollment grew from 130,000 to over 7.87 million (Tang & Zhong, 1993). With such a rapid expansion, it was necessary to ensure that preschool education met certain standards and that there was a degree of consistency in the form and quality of preschool education. Therefore, the State developed guidelines that were to be followed for the establishment of preschool education facilities. At the same time, there was a need to ensure that as many children as possible could benefit from preschool education. Hence, it was decided in 1979 to provide flexible and diversified forms of early childhood services . This guideline has been depicted as the “walking on two legs” preschool education policy (Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government, 1979). In short, this guideline supported the development of alternative forms/modes of funding of kindergarten education. The establishment of both state-funded public kindergartens (one leg) and non-state-funded private kindergartens (one leg) was encouraged to meet the need for early childhood education (Zhu, 2007). The “walking on two legs” policy promoted the development of preschool education in China.

Development of ECE in China (1979–2009)

Between 1979 and 2009, marked progress in ECE was made in the PRC. This was the period which saw major economic and political reforms and marked increase in development and prosperity. These conditions brought new opportunities for the development of preschool education in China. A few of the notable developments during this period included the enactment of laws, the increase in preschool participation, an emphasis on providing quality ECE, an increase in the quality and quantity of kindergarten teachers , and the burgeoning of research in ECE in China.

First, a number of national laws to ensure children’s rights to development and education were enacted. These included Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 1991), Law of the People’s Republic of China on Maternal and Infant Health Care (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 1992), and Education Law of the People’s Republic of China (The State Education Commission, 1995). It is important to note that the Education Law included the State’s obligation to provide preschool education. The PRC also ratified many international treaties to signal the importance placed on children’s rights to survival, health, development, and education. These included the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child (The General Assembly of the United Nations, 1989), the World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children (UNICEF, 1990a), and Plan of Action for Implementing the World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children in the 1990s (UNICEF, 1990b).

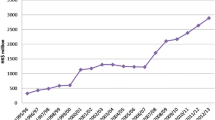

Second, there was a phenomenal increase in preschool participation. While the guiding principle of “walking on two legs” was maintained, amendments to the policy further encouraged various organizations to develop preschool education, through multiple channels, in various forms, in a planned and orderly way, so as to provide more children with the opportunity to receive preschool education. As a result, the preschool enrollment grew from less than 8 million in 1978, to over 28 million in 2009 (Department of Development and Planning, Ministry of Education, 2010; Tang & Zhong, 1993). Although preschool participation markedly increased (see Fig. 4.1), the role of the home environment for early development was also recognized. Parents are children’s first teachers, and a number of documents encouraged parents to provide a favorable home environment for young children . For example, the Working Committee for Women and Children under the State Council issued China’s Outline of Child Development in the 1990s (The State Council, 1992) and China’s Outline of Child Development 2001–2010 (The State Council, 2001), to support parents to care and educate in ways that promote optimal child development. Other services provided to support parent’s caregiving roles included parent education services and classes to promote parent-child bonding. In the context of China’s one-child policy in 1979 (see Sun, & Rao, 2017, Chap. 2), the importance of the preschool experience for young children was also recognized.

Third, there was an emphasis on enhancing the quality of preschool education. This was through focusing on the curriculum and on teacher quality. The academic and professional qualifications of kindergarten teachers were enhanced (see Jiang, Pang, & Sun, 2017, Chap. 6). Between 2001 and 2008, the percentage of teachers with junior college education or above increased from 30.47 to 57.53 % (Department of Development and Planning, Ministry of Education, 2002, 2009). In 2008, the number of university graduates and postgraduates among preschool teachers was 106,660 (Department of Development and Planning, Ministry of Education, 2009). Further, there were many more university-level educational programs for preschool programs, and by 2008, 128 universities and 389 colleges in China had started to train preschool education personnel (see Jiang, Pang, & Sun, 2017, Chap. 6). The professionalization of the teaching force improved the quality of preschool education. Better-qualified preschool teachers were empowered to conduct pedagogical research, to cater to individual students’ learning needs, and to effectively promote children’s learning and development.

Fourth, between 1979 and 2009, there was a great increase in the volume of research into preschool education (Feng, 2015). Both preschool teachers and researchers appreciated the importance of research in raising the quality of preschool education. University-based researchers typically studied the development and education of young children from physiological, psychological, and educational perspectives. Additionally, teachers engaged in action research to enhance teaching quality (Zhu & Wang, 2005). Research has been influential in improving preschool education in China (Feng, 2015). Researchers have also addressed the challenges and difficulties in reforming the preschool education system reform and have endeavored to establish a preschool education system that is both appropriate for the Chinese cultural context and able to meet the society’s needs for quality education.

Difficulties and Challenges (1979–2009)

Though China’s preschool education improved greatly between 1979 and 2009, and there were impressive gains in preschool participation, problems existed. There was a discrepancy between demand and supply, unintended consequences of privatization, poor conditions of service for kindergarten teachers , and marked regional disparities in the availability and quality of preschool education.

Discrepancy Between Demand and Supply

There was an increased demand for preschool education from parents, for educational and custodial reasons. Chinese parents value education highly (see Sun & Rao, 2017, Chap. 2) and see it as a means to upward social mobility. They want their children to be better prepared academically for school so that they will not be behind at the starting line at school. Further, many kindergartens that provided high-quality education charged very high tuition fees that parents could not afford to pay. It has been pointed out that fees in some kindergartens were higher than university tuition fees (Feng, 2015).

The speed of China’s economic growth and accelerating urbanization further fueled the demand for preschool education. There was massive migration from rural to urban areas that affected childcare arrangements. Some young children accompanied their parents to the cities, but some 61 million children are currently “left behind” in rural areas (See Sun & Rao, 2017, Chap. 2). This high level of migration had, and continues to have, significant implications for the care and education of young children. Regardless of whether children migrated with their parents – in which case they could be denied access due to not having permits or hukou – or stayed and got “left behind” in their hometowns, there was an unmet demand for preschool education (Feng, 2015).

Despite the increase in public demand for preschool education, there was a decrease in supply of preschool places. The reform of the economic system in China led to companies/enterprises focusing on increasing production of goods. The companies/enterprises were no longer required to provide childcare facilities for their employees, as this was considered a social welfare benefit. Hence, many kindergartens were closed (Zhang, 2012). A small number of them changed their funding and management structures and became private kindergartens. Later, some kindergartens set up by government agencies and institutions were also closed during the process of streamlining these agencies and institutions, and this further reduced the number of kindergartens in China (Feng, 2015). The total number of kindergartens in the country fell from about 180,000 at the end of the 1990s to about 110,000 in 2000. Between 2000 and 2001 alone, the number of kindergartens in the country decreased by over 64,000. Although there was a rapid increase in the number of private kindergartens afterward, the total number of kindergartens was still below 140,000 in 2009 (Feng, 2015). The decrease in the number of kindergartens was also accompanied by a decrease in the number of children enrolled in kindergartens.

Consequences of the Privatization of Kindergartens

Before 2000, most of the kindergartens in China were funded by the state. Among the five categories of kindergartens mentioned earlier, the majority were funded by the state or by state-owned enterprises (Zeng, 2008). However, with kindergartens being closed, privatizing, or otherwise changing their business framework, the structure of China’s preschool education changed.

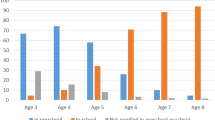

As shown in Fig. 4.2, the proportion of state- or enterprise-funded kindergartens decreased sharply. These kindergartens had met the needs of middle- and low-income families, and a considerable part of the tuition fees was indirectly supported by the state or funded in a large part by these enterprises. Further, many of these kindergartens were located in work premises thereby making them very convenient for parents. The closure of kindergartens set up by enterprises posed problems for middle- and low-income families. Parents had to meet the full costs of preschool education in private kindergartens, and owners of private kindergartens sought to make profits through charging fees (Feng, 2015). They also had to make arrangements for their young children to go to kindergartens that were not located at their work places.

Change in the percentage of public and private kindergartens between 2001 and 2014 (Source: Ministry of Education, 2015b)

The subsidized and convenient kindergartens were replaced with both high-quality private preschools that charged high fees and poor-quality kindergartens that charged lower fees. There was a shortage of high-quality, affordable state-funded kindergartens, and it was difficult for children from low-income families to secure a place in these kindergartens (Feng, 2015).

Further, state-funded kindergartens were mainly located in the cities. These kindergartens, which had better-qualified teachers, tended to meet the needs of government officials, social celebrities, executives, and others from more advantaged social backgrounds. This caused discontent and led to calls for more state-funded, high-quality preschool education for low- and middle-income families.

Status of Early Childhood Educators

According to the Teachers Law of the Peoples’ Republic of China (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 1993), kindergarten teachers should enjoy the same social position and rights as primary and secondary school teachers. However, with primary and secondary education being compulsory and preschool education turning privatized and market oriented, a large gap between the salaries of kindergarten teachers and that of primary secondary school teachers developed. Since Kindergarten teachers commanded lower salaries than primary and secondary teachers and had poorer terms of employment, this led to attrition. This made it difficult for kindergartens to have a stable teaching force and to attract talented personnel (see Jiang, Pang & Sun, 2017, Chap. 6).

Variations in the Quality of Early Childhood Services

The government accorded increasing attention to the quality of ECE and enacted laws and regulations such as Procedural Regulations for Kindergartens (The State Education Commission, 1989) and Guiding Framework for Kindergarten Education (Trial Version) (Ministry of Education, 2001). Local governments also developed curriculum guidelines and standards for kindergartens. However, the pressure to be financially viable and also make profits led some kindergartens to cut expenses, including on teacher salaries and educational resources. Teachers’ qualifications, years of teaching experience, instructional beliefs, and practices vary markedly, and this influences preschool quality. Further, kindergartens wanted to meet parents’ desires for an academic program that were not considered appropriate for young children. As a consequence, there were wide variations in the quality of preschool education (Feng, 2015).

Regional Disparities in Preschool Education

Due to its vast territory and the marked regional disparities in economic development, China adopted a decentralized system for preschool education. Local governments were to take responsibility for funding and managing preschool education. This actually led to even more regional disparities. In Shanghai , the municipal government allocated more public funding to develop preschool education. In 2009, 7.93 % of total funding for education was allocated for preschool education, and the number of government-funded kindergartens accounted for 72 % of the total number of kindergartens (Su, 2010; Xiong, 2015). Shanghai thus had an enrollment rate of 98 % for 3- to 6-year-olds (Su, 2010). On the other hand, in Zhejiang province, 80 % of its kindergartens were privately funded (Department of Education, Zhejiang Province, 2009). The difference in funding sources resulted in differences not only among more developed parts of the country, such as the municipality of Shanghai and Zhejiang province, but across more- and less-developed regions. Some less-developed western provinces did not allocate sufficient public funds for preschool education. With the devolution of responsibility to provincial governments, the central government did not exert sufficient control in terms of regulating the development of preschool education across provinces, different regions in a province, and between urban and rural areas. Some of the problems of preschool education in the PRC between 1978 and 2009 were a consequence of China’s economic reform and subsequent rapid growth. The pace of change far outstripped the government’s ability to deal with the various problems that arose. Furthermore, as a country used to a planned economy , China lacked the experience and resources to solve these issues. Thus, the reform policies were often vague, and the path to reform was difficult; but reform is an exploration. To their credit, early childhood educators and educational administrators at various levels did make relentless efforts to tackle the challenges and difficulties associated with the reform and to find appropriate solutions for the problems that arose (Feng, 2015).

Development of ECE in China (2010 Onward)

After 2009, preschool education was accorded considerable attention by the government. In May 2010, the State Council passed the National Medium and Long-term Education Reform and Development Plan (2010–2020) (Ministry of Education, 2010). The issue of these guidelines was another watershed moment for ECE in China, as preschool education was listed as one of the six major tasks for education development, for the first time. A policy was formulated to universalize one-year preschool education all over the country, mandate two-year preschool education in more developed areas, and require three years’ preschool education in the most developed areas before 2020. The government would also focus on the development of preschool education in rural areas. Therefore, it was necessary to articulate the responsibilities of the government and establish a preschool education system that would be regulated by the government but that integrated both public and private provision (Ministry of Education, 2010).

On November 3, 2010, the State Council executive meeting once again affirmed the importance of preschool education . It was recognized as an important part of the national education system, and the proper care and education of hundreds of millions of children was considered integral to the future of the nation. The state would manage and implement a system for preschool education which would include the urban and the rural areas, and the kindergartens, so that all children could receive a high-quality preschool education.

On November 21, 2010, the Suggestions on Current Development of Early Childhood Education document was issued (The State Council, 2010a) and further emphasized the government’s role in preschool education. The document addressed the problem of inadequate and unfair public funding support in the development of ECE and noted that the government would increase financial resources for preschool education, reexamine the way of funding preschool education, subsidize young children from poor and needy families, and prioritize and promote the development of ECE in rural and western areas through public funding.

At the same time, the State Council convened the relevant ministries to develop national guidelines and to propose specific measures for promoting preschool education. Most notably, it was decided that 50 billion yuan was to be invested to promote preschool education in rural areas in the middle and western regions from 2011 to 2015. It is the first time in China’s history that the central government has apportioned special funds for preschool education, and this was a very significant development, for three reasons (The State Council, 2010b).

First, this development is a concrete manifestation of the implementation of the government’s responsibility in the development of preschool education. It is also considered as an important guarantee for the implementation of the Plan (Ministry of Education, 2010). Second, it is an important measure to promote equality at the starting point of school education, given that administrative and financial responsibility and funding were devolved to provincial and local governments. In poor and rural areas, limited funding had been allocated to preschool education, and this was not conducive to the development of preschool education in poor areas. This time, the central government is committed to provide financial support expenditure for the following: the expansion and reconstruction of kindergartens in the middle and western regions and in the poverty-stricken areas in the eastern region; private kindergartens which charge low tuition fees and serve the public and support the collective body, the establishment of kindergartens by enterprises and institutions, a national teacher training program for kindergarten teachers in the middle and western regions, and for local governments to establish a subsidy system for preschool education for poor children (Ministry of Education, 2010). These policies prioritize the needs of underprivileged children, to rectify the previous unfair distribution of public funding for preschool education.

Third, it recognized the importance of establishing a comprehensive state-funded system (Liu & Pan, 2013). As noted earlier, preschool education was thought of as a social welfare benefit, and it did not receive much public finance. The government’s new policy to develop preschool education included funding. China’s preschool education has entered a new phase. However, the process of system development is a long and hard task. From the perspective of sustainable development, preschool education does not only need special support from public finance during special periods for certain situations. It is more important to establish a long-term mechanism. Therefore, the nation needs to start from actual conditions, look into the future, and design an efficient and effective system.

According to the Evaluation Report of National Medium and Long-term Education Reform and Development Plan (2010–2020) (Ministry of Education, 2015c), great achievement has been made in terms of:

-

1.

A substantial increase in gross enrolment rate of ECE, from 50.9 % in 2009 to 70.5 % in 2014

-

2.

A rapid expansion of resources for ECE, with an increase of 51.88 % in the total number of kindergartens and 87.05 % in the number of preschool teachers

-

3.

Particular support for rural areas to develop ECE, with an increase of 13,899 kindergartens in rural areas, from 2011 to 2014

-

4.

Initial establishment of ECE network to benefit children universally, by supporting the establishment of different types of public kindergartens and private kindergartens providing ECE services with universal benefits

-

5.

Substantial increase in financial investment in ECE, with a total investment of ¥ 69 billion from the central government and over ¥ 200 billion from local governments from 2010 to 2014

-

6.

The establishment of financial support for parents, with over 8 million children benefitted from the support

-

7.

Significant improvement in preschool teachers in both quantity and quality

-

8.

Gradually regularized ECE monitoring system

-

9.

An overall satisfaction with ECE from society, with the satisfaction rate from parents ranging from 70–90 % and the average satisfaction rate from principals 82.85 %

Support for Migrant and “Left-Behind” Children

A recent survey considered the needs of parents who were migrant workers in different provinces and municipalities and who had preschool children. They found that there was a great demand for preschool education that was convenient, and of low cost, but that parents wanted children to have an academic preschool curriculum which focused on reading and mathematics. Many of their children had access to ECE. However, most of the kindergartens were unregistered and of low quality. Results also showed that most of the migrant families who brought their children into cities planned to remain in the cities with their children (Feng, 2015). Therefore, there is an urgent need to provide high-quality preschool education to children of migrants. Similarly, there is a pressing need for high-quality ECE for children who are left behind in rural areas, when their parents migrate to urban areas. Studies have found that left-behind children were more likely to have problems in social development. For instance, they have psychosocial difficulties and emotional difficulties, experience bullying, and have poor daily living habits. These problems are partially due to their separation from parents (Wen & Lin, 2012; Ye & Pan, 2011; Fan, Su, Gill, & Birmaher, 2010). More measures should be adopted to enhance parent-child interaction for these children, and more opportunities should be created for children to have reunions with their parents.

Status of Kindergarten Teachers

While the Teacher Law of the People’s Republic of China (Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, 1993) safeguards the rights and benefits of teachers, the legislation only includes teachers in publicly funded kindergartens. However, as noted earlier, most kindergarten teachers work in private kindergartens and are not formally recognized as “teachers,” as they do not have bianzhi, a hallmark of a formal teacher, especially in rural areas (Hu & Robert, 2013). Therefore, these teachers do not receive the same wages, benefit, and privileges provided to teachers in publicly funded kindergartens. A survey in Anhui province found that in rural areas, about 76 % of the kindergarten teachers had a strong wish to leave their job. Teachers who were younger, who had higher educational qualifications, and who received relatively lower wages reported that they were more likely to resign than other teachers (Feng, 2015). Hence, teacher wastage and attrition continue to be problems in the preschool sector.

Conclusions

It is clear that the PRC has entered a new and positive era for preschool education, bolstered by facilitative and sensible government policies and measures. Effective implementation of reform measures is not an easy task, and there will undoubtedly be challenges in making changes. There may also be some unexpected consequences. However, the will and the skill to make changes are in place, and preschool education in the PRC is poised to have a bright future.

Notes

- 1.

Before 1994, data from the Ministry of Education was only provided for the three types of public kindergartens. From 1994, data are also provided for private kindergartens.

- 2.

This categorization applies to mainstream local kindergartens.

References

Compilation Group of the History of Preschool Education in China. (1989). Selection of materials on the history of preschool education in China. Beijing, China: The People’s Education Press.

Department of Development and Planning, Ministry of Education. (2002). Educational statistics yearbook of China 2001. Beijing, China: The People’s Education Press.

Department of Development and Planning, Ministry of Education. (2009). Educational statistics yearbook of China 2008. Beijing, China: The People’s Education Press.

Department of Development and Planning, Ministry of Education. (2010). Educational statistics yearbook of China 2009. Beijing, China: The People’s Education Press.

Department of Education, Zhejiang Province. (2009). Statistical communiqué on Zhejiang education development in 2009. Retrieved October 10, 2014, from http://www.zjedu.gov.cn/news/16154.html

Fan, F., Su, L. Y., Gill, M. K., & Birmaher, B. (2010). Emotional and behavioral problems of Chinese left-behind children: A preliminary study. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(6), 655–664.

Feng, X. X. (2015). Early childhood education in China: Moving forward through reforms. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government. (1951, October 1). Decision to change the education system. Retrieved October 10, 2014, from http://www.reformdata.org/content/20130222/17235.html

Government Administration Council of the Central People’s Government. (1979, October 11). Minutes of national meeting on nursery and kindergarten education. Retrieved November 15, 2014, from http://www1.people.com.cn/item/flfgk/gwyfg/1979/L35301197904.html

Hu, B. Y., & Roberts, S. K. (2013). A qualitative study of the current transformation to rural village early childhood in China: Retrospect and prospect. International Journal of Educational Development, 33(4), 316–324.

Jiang, Y., Pang, L.J., & Sun, J. (2017). Early childhood teachers’ professional development in China (Chapter 6). In N. Rao, J. Zhou, & J. Sun (Eds.), Early childhood education in Chinese societies. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Lascarides, V. C., & Hinitz, B. F. (2011). History of early childhood education. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis.

Liu, Y., & Pan, Y. J. (2013). A review and analysis of the current policy on early childhood education in mainland China. International Journal of Early Years Education, 21(2–3), 141–151.

Ministry of Education. (2001, July 2). Guiding framework for kindergarten education (Trial version). Retrieved December 20, 2014, from http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2002/content_61459.htm

Ministry of Education. (2010, July 29). National medium and long-term education reform and development plan (2010–2020). Retrieved December 10, 2014, from http://www.moe.edu.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_838/201008/93704.html

Ministry of Education., National Development and Reform Commission. & Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. (2014, November 3). Suggestions on implementing the second round of three-year action plan for early childhood education. Retrieved November 11, 2015, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A26/s3327/201411/t20141105_178318.html

Ministry of Education. (2015a, July 30). Statistical communiqué on national education development in 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2015, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201507/t20150730_196698.html

Ministry of Education. (2015b). Educational statistics database. Retrieved October 10, 2015, from http://www.moe.edu.cn/s78/A03/moe_560/jytjsj_2014/

Ministry of Education. (2015c, November 24). Evaluation report of national medium and long-term education reform and development plan (2010–2020): early childhood education. Retrieved December 1, 2015, from http://www.eol.cn/html/jijiao/xiao/2015ghgy/

Ministry of Health & Ministry of Education. (2010, September 6). Measures for the healthcare management of nurseries and kindergartens. Retrieved October 15, 2014, from http://www.moh.gov.cn/mohzcfgs/pgz/201010/49391.shtml

Ministry of Labor and Personnel & the State Education Commission. (1987, March 9). Standards for the institutional organization of day and boarding kindergartens. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A26/jces_left/moe_705/s3327/201001/t20100128_82001.html

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. (1990, December 28). Law of the People’s Republic of China on the protection of disabled persons. Retrieved November 10, 2014, from http://www.gov.cn/banshi/2005-08/04/content_20235.htm

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. (1991, September 4). Law of the People’s Republic of China on the protection of minors. Retrieved October 15, 2014, from http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?lib=law&id=5624&CGid=

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. (1992, October 1). Law of the People’s Republic of China on maternal and infant health care. Retrieved January 10, 2015, from http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?lib=law&id=4492&CGid=

Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. (1993, October 31). Teachers law of the People’s Republic of China. Retrieved October 10, 2014, from http://www.npc.gov.cn/englishnpc/Law/2007-12/12/content_1383815.htm

Su, L. (2010, August 5). How to solve the problems of difficult access to kindergartens and the high tuition fees? China Education Daily. Retrieved from http://www.jyb.cn/china/gnsd/201008/t20100805_380076.html

Sun, J., & Rao, N. (2017). Growing up in Chinese families and societies (Chapter 2). In N. Rao, J. Zhou, & J. Sun (Eds.), Early childhood education in Chinese societies. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Tang, S., & Zhong, Z. H. (1993). History of Preschool Education in China. Beijing, China: The People’s Education Press.

The General Assembly of the United Nations. (1989, November 20). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

The State Council. (1992, February 26). China’s outline of child development in the 1990s. Retrieved July 30, 2014, from http://www.wsic.ac.cn/policyandregulation/47666.htm

The State Council. (2001, May 22). China’s outline of child development 2001–2010. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/zwgk/fvfg/shflhshsw/200711/20071100003401.shtml

The State Council. (2010a, November 3). The State Council executive meeting chaired by Premier WEN Jiabao to develop political measures to promote early childhood education. Retrieved November 20, 2014, from http://www.gov.cn/ldhd/2010-11/03/content_1737322.htm

The State Council. (2010b, November 21). Suggestions on current development of early childhood education. Retrieved November 25, 2014, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_1778/201011/111850.html

The State Education Commission. (1989, June 5). Procedural regulations for kindergartens. Retrieved October 10, 2014, from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A02/s5911/moe_621/201511/t20151119_220023.html

The State Education Commission. (1995, March 8). Education law of the People’s Republic of China. Retrieved July 20, 2014, from http://old.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_619/200407/1316.html

UNICEF. (1990a). Plan of action for implementing the world declaration on the survival, protection and development of children in the 1990s. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.unicef.org/wsc/plan.htm

UNICEF. (1990b, September 30). World declaration on the survival, protection and development of children. Retrieved October 20, 2014, from http://www.unicef.org/wsc/declare.htm

Wen, M., & Lin, D. H. (2012). Child development in rural China: Children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Development, 83(1), 120–136.

Xiong, B. Q. (2015, August 25). Providing children with more access to public kindergartens. China Youth Daily. Retrieved from http://zqb.cyol.com/html/2015-08/05/nw.D110000zgqnb_20150805_4-02.htm

Ye, J. Z., & Pan, L. (2011). Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labour migration on left-behind children in China. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(2), 355–377.

Zeng, X. D. (2008). A design of an appropriate early childhood education funding system in China. Chinese Education & Society, 41(2), 8–19.

Zhang, Y. (2012, February 24). The proportion of governmental financial investment in early childhood education should be clarified in legislation of early childhood education. Legal Daily. Retrieved from http://epaper.legaldaily.com.cn/fzrb/content/20120224/Articel03004GN.htm

Zhu, J., & Wang, X. C. (2005). Contemporary early childhood education and research in China. In B. Spodek & O. N. Saracho (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives in early childhood education, Vol. (7): International perspectives (pp. 55–77). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Zhu, J. X. (2008). Implementation of and reflection on Western thought in early childhood education in the Chinese mainland. Journal of Basic Education, 17(1), 3–16.

Zhu, M. J. (2007). A review on the development of early childhood education in China. Retrieved December 10, 2014, from http://child.cersp.com/sTsg/sJywz/200707/1062.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Feng, Xx. (2017). An Overview of Early Childhood Education in the People’s Republic of China. In: Rao, N., Zhou, J., Sun, J. (eds) Early Childhood Education in Chinese Societies. International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development, vol 19. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1004-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1004-4_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-024-1003-7

Online ISBN: 978-94-024-1004-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)