Abstract

This chapter focuses on the policy proposal of flexicurity – the creation of labor market institutions that facilitate both flexibility and security for employers and employees. In substance, the flexicurity proponents argues that employment protection legislations should be liberalized, but such liberalization should be compensated by more generous unemployment benefits in combination with active labor market measures. However, a side effect of flexicurity could be an increase in job insecurity with adverse effects on well-being. This chapter investigates such outcomes among employees by studying the effect of central labor market institutions in 26 European countries. The main results are in line with the flexicurity proposal. No significance of the strictness of employment protection legislation are found for neither subjective job insecurity nor well-being, while both the use of passive and active labor market measures are important to reduce negative effects in these regards. The chapter ends with a discussion about how realistic the flexicurity proposal is in times of economic crises and austerity in Europe.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Flexicurity

- Labor market institution

- Unemployment benefits

- Active labor market measures

- Job insecurity

- Employment legislation

- Employment protection

- Economic crises

- Austerity

1 Introduction

European labor markets have since the 1980s often been described as “sclerotic” by critics who believe that these economies are stagnating in comparison to important global competitors. The labor markets in Europe are seen as too rigid because of the extensive social protection which could hamper necessary flexibility in a global economy where both job destruction and job creation are accelerating (Sapir 2006). Job protection is said to slow down employers’ adaptation to market changes, and generous unemployment benefits are believed to make the unemployed more choosy, thus prolonging their time in unemployment and increasing minimum wages. Unemployment rates therefore reach a higher level compared to less regulated labor markets, such as the United States.

However, not everyone agrees on this negative description of European labor markets. Generous welfare states and regulated labor markets have also been a great success in reducing poverty, equalizing living conditions, and humanizing working life. Nonetheless, Europe is not a homogenous region and there are great variations among countries on many important indicators, for example, GDP per capita or unemployment rate. Northern Europe, and more specifically the Scandinavian countries, is usually ahead on these. Other European countries, especially in Eastern Europe, fare worse.

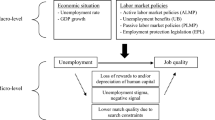

During the past decade, there has been a rather intensive debate as to whether social protection necessarily contradicts flexibility in the labor market and the economy. Or, the other way around, is flexibility always something that destroys social security? At the centre of this debate is the proposal of “flexicurity”, a concept combining the words flexibility and security (Wilthagen and Tros 2004). It was first used in the Netherlands in the mid-1990s in a discussion of the necessity to flexibilize the labor market by reducing job protection for permanent employees and at the same time improve the protection of temporary workers (Wilthagen 1998). Later in the nineties, it was also used to describe the institutional characteristics of the labor market in Denmark, where a whole flexicurity system has been established (Jørgensen and Madsen 2007). Its main features are very liberal employment protection legislation, combined with generous unemployment benefits and extensive use of active measures for the unemployed (e.g., training, subsidized jobs). In 2007, the European Commission also drew attention to the concept and in a so-called Communication recommended the member states pay attention to principles of flexicurity (European Commission 2007).

A main message of flexicurity proponents is that job protection should be replaced by employment security. In this regard, one should not create policies that secure particular jobs, but instead facilitate the creation of new jobs and transitions of the labor force to them. The labor force should in this way still enjoy the security of staying employed, but not necessarily in the same jobs. Paradoxically, a flexicurity system could therefore result in higher levels of job insecurity for employees. However, the negative effects of job insecurity should be mitigated by generous unemployment insurance (UI) and extensive use of active labor market measures, besides a flourishing economy in general where new jobs are available.

This chapter will focus on the central aspect of job insecurity and its relationship to well-being. The question we will try to answer is whether the labor market institutions emphasized in the flexicurity discourse have significance in mitigating job insecurity and its presumed negative effects on well-being. In our research, we used a cross-European data set – the European Working Conditions Survey – and an analytic strategy called multilevel regression analysis. In this way, the impact of factors belonging to the individual level and the contextual level can be differentiated.

In particular, national institutional factors related to employment protection legislation, unemployment insurance, and active labor market policies, beside the general state of the economy indicated by unemployment level, occupy the centre of attention in this chapter. In the next sections, we will discuss some of the theoretical issues concerning job insecurity, well-being, and labor market institutions, then present our research data, methods, and results. The chapter will end with a discussion of the relevance of labor market institutions to mitigate the problems of job insecurity and related ill health. Does flexicurity show promise in this regard?

1.1 Job Insecurity and Well-Being

In modern societies, paid work is the most important factor behind the capacity of individuals to fend for themselves and their households. Other income sources can in some circumstances replace a wage or salary: for example, support from family and friends, savings, income from capital, or benefits from the welfare state. However, these sources are often of limited duration. Furthermore, a job is more than just the manifest function of generating economic means; a job also creates a sense of meaningfulness and social belonging. These are examples of what Marie Jahoda (1982) calls a job’s latent functions.

Job insecurity has to do with the risk of losing the job, and as mentioned, it is a threat with potential serious consequences for employees. The policy idea of flexicurity – to increase job insecurity (decrease job protection) and facilitate transitions between jobs – may thus, from an employee perspective, look like a rather risky endeavor.

The concept of job insecurity has several meanings in social science. Usually, a first distinction is made between objective and subjective job insecurity (De Witte 2005; Sverke et al. 2002). The first has to do with the objective risk of a job loss, for example, because of the temporary character of a job contract or lay-off decisions in an organization. Subjective job insecurity, on the other hand, is the employee’s perception of the risk of losing the job. This subjective perception does not need to be a correct assessment of the situation. It may be a judgment made on the basis of wrong information or colored by a feeling of being at risk. However, an employee’s assessment of the risk has been shown to have a rather strong relationship to the objective risk of losing the job (Dickerson and Green 2012).

It is also possible to separate between different aspects of the concept of subjective job insecurity. Some researchers distinguish between cognitive and affective job insecurity (Anderson and Pontusson 2007; Borg and Elizur 1992; Huang et al. 2010). The cognitive refers to individuals’ assessment of the risk of losing the job and the affective to emotional reactions to the perceived risk, where worries are a typical response. This distinction makes it possible to understand that perceived risks of a job loss are not always accompanied with fears or worries. Or, conversely, that worries of a job loss are not always combined with a direct perceived threat.

However, other researchers regard these aspects as more intermingled and emphasize that individuals’ judgments are colored by subjective factors of how the situation is perceived (De Witte 2005). One essential factor in this regard is whether they have any means to handle the particular situation or whether they are only victims of the circumstances. Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984) stress that the ability to cope with a threatening situation is related to the emotional reaction to it: If we perceive a threat and find no means to handle it, our worries will be intensified.

One factor that can enable workers to cope with job insecurity is if job alternatives exist in the external labor market (De Cuyper et al. 2008). In the flexicurity paradigm, this is referred to as employment security. For example, Berglund et al. (2014) show that the assessment of good possibilities to find an equal or better job in the labor market reduces worries of losing the present job (affective job insecurity). Furthermore, the strong connection between an employee’s assessment of the risk of losing the job (cognitive job insecurity) and worries connected to a job loss is reduced when the employee sees opportunities in the external labor market.

What effects are attributed to job insecurity? Research shows that job insecurity is related to phenomena such as organizational commitment, turnover intention, and job dissatisfaction (Sverke et al. 2002; Cheng and Chan 2008). Of central importance in the present context is that job insecurity is also related to health and well-being. One explanation for this is that job insecurity works as a serious stressor in (working) life (De Witte 2005; Vulkan 2012). Job insecurity implies a threat to a sustainable life situation by the potential loss of the manifest and latent functions of a job (Jahoda 1982). This threat may be more severe if the employee has limited or no means to cope with the situation.

The core question in the present study is whether the institutional context of a country, that is, the rights and resources that residents are entitled to and which are provided by national authorities, can also serve as a means to cope with the expected adverse effects of job insecurity on well-being.

1.2 Labor Market Institutions

In the literature of flexicurity, and in particular in the description of the flexicurity system of the Danish labor market, the metaphor of a “Golden Triangle” has been used (OECD 2004: 97–98; Bredgaard et al. 2005). The three corners of the triangle represent the central pillars of the system. One corner represents the very flexible character of the labor market with liberal employment protection legislation. Employers therefore have very few obstacles when it comes to layoffs. This creates numerical flexibility which results in high mobility flows to and fro employment (Berglund et al. 2010).

The second corner represents the social protection that the welfare state provides. Especially emphasized is the generous UI policy in Denmark. In the mid-2000s, it compensated up to 90 % of the previous wage (although with a ceiling), with a duration up to 4 years (Berglund et al. 2010: 239ff.). An important side effect of the generous UI is that it made employees and unions in Denmark more ready to accept a low level of job protection in the labor market (Bredgaard et al. 2005: 24ff).

The third corner in the triangle represents investment in active labor market policies. These measures have the purpose of reducing the negative impact of unemployment by activating the unemployed in their job search efforts and adapting the human capital of the unemployed to the demand in the labor market by providing vocational training. However, active labor market policies were a rather late piece in the Danish arsenal to combat unemployment (Lindvall 2010: 153ff). They were introduced in the beginning of the 1990s and were essential in the efforts to bring down the high level of unemployment at that time.

In summary, the Danish flexicurity system implies high levels of mobility in the labor market and in this regard a high level of objective job insecurity. However, for employees this insecurity is compensated for by generous unemployment benefits and active measures that help unemployed back to work. From a theoretical point of view, these compensating institutions may reduce the negative impact of job insecurity, for example, on well-being. In this chapter, we will test whether these are reasonable expectations by relating different countries’ relevant institutional characteristics to subjective job insecurity and well-being. The analysis in the following three sections will focus on 26 European countries, as we describe the variations across the countries with regard to these institutions.

1.2.1 Employment Protection Legislation

As an indication of how employment protection legislation (EPL) differs among the countries, we use the OECD indices on the strictness of EPL. The index is a summation of three different features of the legislation (Venn 2009). The first feature indicates which rules have to be taken into account when employees with permanent (no time limit) contracts are fired. Relevant examples are rules about notice periods or special grounds for dismissal. The second feature concerns rules in the case of collective layoffs, for example, if the public employment office has to be given notice. The third feature is a focus on the rules regarding temporary contracts, for example, in which types of work these are allowed and what is the maximum duration. These aspects of EPL have been weighted and combined by OECD into one overall indicator (Fig. 9.1).

Employment protection legislation, 2008. Overall strictness. OECD Version 2 (Main source: OECD (2010), “Employment Protection Legislation: Strictness of employment protection legislation: overall”, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database). doi: 10.1787/data-00317-en (Accessed 14 March 2013). For Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania, the source is Sabina Avdagic, Causes and Consequences of National Variation In Employment Protection Legislation In Central And Eastern Europe, ESRC project RES–061–25–0354)

The indices in Fig. 9.1 range between 0 and 6, where higher numbers indicate stricter legislation. The figure shows a rather large variation in protection among the countries. At the low end are the UK and Ireland with liberal legislation. If we had included more OECD countries, we would have found the US with the lowest index (0.65) together with other Anglo-American countries. In the European context, Denmark has a relatively liberal legislation – in line with the flexicurity expectation. Strict legislation is found in many Mediterranean countries such as Spain and Portugal, and the strictest legislation among the presented countries is that of Luxemburg.

1.2.2 Passive Labor Market Policies

The use of unemployment benefits and other measures to reduce the economic consequences of unemployment also varies among countries, and the construction of the UI has great consequences for the generosity of the benefits. The rules can vary with respect to eligibility, on the compensation rate, and how long one can continue to receive the benefit. In the present context, a rather crude indicator will be used. It is the expenditure on passive labor market policies (PLMPs) as percentage of GDP. However, PLMPs also include costs for early retirement for labor market reasons, beside the costs of unemployment insurance. In some countries (Belgium, Poland, and Slovakia) early retirement constitutes a substantial share of the passive measures, but not in most of the countries, although Denmark has a rather high figure (23 % of the costs of passive measures in 2010).

Figure 9.2 shows the expenditure on passive measures as percentage of GDP for 2010. The highest proportions of expenditure are found in Spain and Ireland, two countries that were hit very hard by the financial and Euro crises. Greece is another of the countries in crisis, although with much lower spending on passive measures. Denmark, together with the other flexicurity country, the Netherlands, is found in the upper end of the diagram. At the low end are the UK, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Sweden, a country historically known for its generous social spending, is also found towards the lower end, to a large extent because of changes and cuts in its UI in 2007 (Bengtsson and Berglund 2012).

1.2.3 Active Labor Market Policies

Active labor market policies (ALMPs) refer to measures that activate the unemployed during their unemployment spell. Some measures are intended to stimulate job search efforts, others to improve or change the human capital of unemployed persons by vocational training. Sometimes the measures directly create or subsidize jobs for the unemployed. In the present analysis, we use an overall indicator of ALMPs, which, as previously, refers to expenditures on ALMPs as percentage of GDP.

Figure 9.3 shows that Denmark and Belgium are the countries with the highest percentage spending on ALMPs. However, two other Nordic countries, Finland and Sweden, are also found at the top. In many ways, ALMPs can be said to be a Nordic invention; in Sweden, they were already in use in the late 1950s to facilitate the restructuring of the economy (Bonoli 2010). It was not until the 1990s that ALMPs became more widespread in Europe. In some countries the political will to use ALMPs is more modest. This is the case for many Eastern European countries as well as the UK.

1.3 Expected Significance of Labor Market Institutions for Job Insecurity and Well-Being

Let us now return to the question of the significance of these institutions – EPL, PLMPs, and ALMPs – for employees’ perceptions of job insecurity and well-being. Which expectations would be reasonable with regard to how they might affect employees?

A starting point is to turn to institutional theories and their perspectives on how institutions affect actors. Institutions are usually defined as “the rules of the game,” the formal or informal rules that constrain and make social interaction more predictable (Hall and Soskice 2001: 9; North 1991). Actors are believed to develop cognitions, norms, and evaluations in relation to institutions. They often have knowledge about how the institutional rules are working and develop normative expectations of appropriate behavior in relation to them. Furthermore, institutions can be contested by the actors; that is, do they serve the actors in the pursuit of valued goals?

The institutional perspective gives a rationale to believe that the institutional order in different countries may affect individuals’ assessments and affective responses to their situation in the labor market. For example, the existence of employment protection legislation may influence how one assesses the risk of losing a job. For example, in the Swedish legislation there is a well-known rule of “last in, first out” when collective layoffs take place. This should make seniority an important factor behind the assessment of the risk – which is actually the case (Berglund et al. 2014). However, what does the research say about the effects of EPL, PLMPs, and ALMPs on actors, and in particular, employees?

Employment protection legislation has long been a subject of discussion, especially the consequences of EPL for employers’ firing and hiring decisions (Skedinger 2008; OECD 2010). The general view among researchers is that strict EPL slows down both hiring and firing, with the consequence that those already employed are relatively protected but the unemployed have difficulty getting new employment. However, if temporary employment is allowed, it can work as an alternative way for employers to obtain flexibility and lead to a greater use of these contracts. A possible consequence is therefore a dualization of the labor market with relatively protected jobs in a core, but higher levels of job insecurity in the periphery of employees with temporary contracts.

Following this reasoning, several consequences of EPL are expected in relation to subjective job insecurity, and ultimately to well-being. Firstly, the strictness of EPL is expected to correlate negatively with subjective job insecurity; that is, the higher the protection, the less perceived job insecurity. Secondly, EPL and employment contracts may interact, implying higher levels of job insecurity among temporaries in labor markets with strict EPL than in markets with more liberal legislation. A third potential effect is related to the significance of employment security (the security of having job options in the labor market). Following the flexicurity formula, employment security becomes more important to reduce job insecurity in labor markets with liberal EPL than in labor markets with stricter EPL.

The generosity of passive measures, especially UI, may also be important for job insecurity and well-being. Generally, UI is believed to have significance for the unemployed in that generosity can prolong the unemployment spell (Layard et al. 1991; OECD 2010). However, there are researchers that believe that UI affects the employed as well. Sjöberg (2010) argues that the UI works as any other insurance and reduces feelings of economic vulnerability in case of a job loss. Following this reasoning, it is possible that the generosity of passive measures (PLMPs) reduces subjective job insecurity. Furthermore, job insecurity and generosity of PLMPs may also interact in that the negative impact of job insecurity on well-being becomes less strong, the higher the spending on PLMPs.

When it comes to active labor market policies (ALMPs), it is much harder to predict any conclusive relationships that it can imply for employees. In the flexicurity literature, ALMPs are believed to affect the behavior of the unemployed (Bredgaard et al. 2005). On the one hand, a motivation effect increases the search effort of unemployed persons because the measures they are assigned to during the unemployment spell are not perceived as so positive and a new job can be a way to escape those measures. On the other hand, the measures can improve (or decrease the erosion of) the human capital of the unemployed by vocational training. In the present context, however, governmental spending on ALMPs may also work as a signal to employees that efforts are going to be made by the state to reduce the negative effects of unemployment. This may also reduce feelings of job insecurity and improve well-being.

Is there any support for these expectations in previous research? Anderson and Pontuson (2007) find a clear negative relationship between the strictness of EPL and job insecurity, while Erlinghagen (2008) cannot confirm this relationship and Sjöberg (2010) does not find any relationship between EPL and well-being either. However, Chung and Van Oorschot (2011) show that EPL and employment contracts interact in relation to job insecurity in an unexpected way, indicating a smaller impact of the employment contract (permanent or temporary) on job insecurity when EPL is stricter.

Anderson and Pontuson (2007) also find that the generosity of UI reduces the worries of losing a job. However, the same significance is not found for ALMPs. Sjöberg (2010) finds a significant impact of the generosity of UI on subjective well-being. He also discovers that the generosity of the UI and unemployment experiences among employees interact, showing less significance of unemployment experience on well-being in countries with a more generous UI.

Erlinghagen (2008) do not find any relationship between social spending (which includes the UI) and job insecurity. The only higher-level relationship that is found is to the long-term unemployment rate (the higher the rate of unemployment, the greater the risk of job insecurity). Similar results are shown in Esser and Olsen (2012), who reveal a significant relationship between job insecurity and the unemployment rate. Chung and Van Oorschot (2011) only find weak support for the significance of labor market policies when the impact of economic conditions are controlled for (employment rate and GDP growth rate).

This brief overview thus shows mixed results concerning the significance of the labor market institutions pointed out as vital for the flexicurity formula. No straightforward answer is given to the question whether employment protection legislation decreases job insecurity or spending on active and passive measures can compensate for reduced security. However, less ambiguous are results showing that unemployment increases insecurity in the labor market. Consequently, this is an important factor to consider when evaluating the significance of labor market institutions. We now turn to our own analysis of these matters.

2 Method

The data used in this chapter are from the European Working Conditions Survey 2010 (EWCS 2010) administered by Eurofound, Dublin.Footnote 1 Data were collected in 34 European countries, although in the following analyses only 26 countries are included (Norway and “EU 27” except Cyprus and Malta). The restriction of countries is due to missing data on the national level for some of the indicators. The general purpose of the survey is to provide data on working conditions; it uses random sampling of persons above 15 years residing in the country and employed in the reference week. Achieved sample sizes vary between 1,000 and 4,001 (Eurofound 2010).

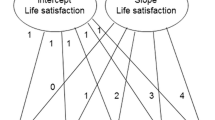

In the present study, we used multilevel regression methods. These methods are appropriate when data are nested and exist on different levels (Hox 2002). In this case two levels are considered. The first is the individual level, which measures characteristics of the individual. The second level is country, which constitutes the context for individuals, that is, individuals are nested within countries. In the following analyses, we expected that variations in national contexts, for example, regarding the strictness of employment protection legislation, could affect the inhabitants’ perceptions of their job insecurity and well-being.

2.1 Dependent Variables: Job Insecurity and Well-Being

Job insecurity was measured by responses to the following statement in EWCS: I might lose my job in the next 6 months. The respondent had five options, from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” In terms of the foregoing theoretical discussion, this indicator may in the first instance be regarded as a measure of cognitive job insecurity (Berglund et al. 2014). However, we were not able to control for the affective element of job insecurity, which makes it most safe to look at as an indicator of subjective job insecurity, including both cognitive and affective elements.

As mentioned, the second dependent variable of interest is well-being. In the EWCS questionnaire, the WHO-5 Well-Being Index developed by the World Health Organization is used to measure mental well-being (McDowell 2010). Five statements are given about the respondents’ mood: if they are cheerful and in good spirits, feel calm and relaxed, etc. There are six response alternatives which range from “All of the time” to “At no time”. The items are summated into a scale ranging between 0 and 25 (α = 0.88).

2.2 Independent Variables

Following the logic of multilevel analysis, independent variables on both individual and country level were used. On the individual level, variables present in the questionnaire and known from previous research to be related to job insecurity or well-being were considered for the models (Berglund et al. 2014; Erlinghagen 2008; Näswall and De Witte 2003; Vulkan 2012). In the end, however, only ten variables with statistically significant relationships were kept in the final regression models.

Beside standard variables such as gender, age, contract (permanent vs. temporary), sector (private vs. public), and occupational group, the individual-level model analyzing job insecurity includes indicators of influence and social support in the work situation. Furthermore, a variable measuring economic hardship is included, indicated by the question: Thinking of your household’s total monthly income, is your household able to make ends meet? Six answering alternatives are provided, ranging from “Very easily” to “With great difficulty.” An index measuring somatic complaints is used, measuring backache, muscular pains in shoulders, neck and/or upper limbs, and muscular pains in lower limbs (α = 0.72). The last variable in the model measures employment security by the question: If I were to lose or quit my current job, it would be easy for me to find a job of similar salary. The respondent could agree or disagree, on a five-point scale.

Concerning well-being, almost the same model is used except for some changes. First, neither employment contract nor sector showed any significant relationships to well-being and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Secondly, two new variables were introduced. The first measuring work–life balance: In general, do your working hours fit in with your family or social commitments outside work very well, well, not very well, or not at all well? The second question asks about demands in the work situation: Over the last 12 months how often has it happened to you that you have worked in your free time in order to meet work demands? The respondent could answer whether that happened nearly every day, once or twice a week, once or twice a month, less often, or never. A third change is that the variable measuring job insecurity also is included in the analysis.

The second level in the analysis includes variables indicating contextual characteristics of the countries. The first is employment protection legislation: the OECD summated index that is used as an indicator (see note 1). The second and third variables are the expenditures on passive or active labor market policies as percentage of GDP (Source: Eurostat, see above). Beside these theoretically central variables, unemployment level in 2010 is also included to control for the situation in the national labor markets (Eurostat data). This is especially important when it comes to the spending on PLMPs and ALMPs. The size of the spending is obviously related to the unemployment level and is therefore necessary to control for in the models. Beside unemployment level, GDP per capita have also been tested, although without showing any significant effect on either job insecurity or well-being. The variable is therefore left out of the models.

3 Results

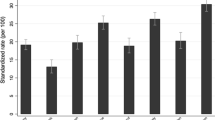

The following analyses focus on the variation in job insecurity and well-being in 26 European countries. Figures 9.4 and 9.5 show the mean values of these variables. A first observation is that the variation among countries seems greater for job insecurity than for well-being. Countries with high levels of job insecurity are often found in Eastern Europe. Norway and Denmark have the lowest levels; for well-being, the same two countries are top scorers, together with Ireland, while many Eastern European countries exhibit the lowest levels.

3.1 Individual-Level Factors

Proceeding with the regression analysis, Table 9.1 shows a null model and an individual level (Model 1) without country-level variables present. Focusing first on job insecurity and the impact of the independent variables in Model 1, we find several expected relationships. The most important factors are temporary employment and economic hardship. Both have rather large positive impact on subjective job insecurity (increasing insecurity). Other factors to notice are that both influence and social support in the work situation reduce job insecurity. Furthermore, employment security, that is, perceived good opportunities in the labor market, reduces job insecurity.

Due to the large numbers in the analysis (n = 22,731), there are also many more or less trivial significant results, for example, the effect of gender. However, before concluding that these factors are trivial in explaining job insecurity, one has to consider that there are also national variations in the size of the coefficients. In some countries, therefore, the impact may be stronger and in others weaker or even going in an opposite direction. In the present analysis, only the coefficients of gender, occupational group, and somatic complaints do not show any statistically significant country variation. This means that the other coefficients can be both stronger and weaker in the different countries. What is shown, therefore, is an average (fixed) effect of the variables in the population of countries.

The null model decomposes the total variance of the dependent variable into individual-level and country-level variance (Hox 2002: 15). This makes it possible to estimate how much of the total variance is related to the country level – approximately 11 % in the present case. However, some of this variance may be due to how the samples are composed in different countries, for example, how frequent temporary contracts are. This may affect the general level of insecurity in a country. Model 1 controls for many of such effects; about 38 % of the country-level variance is explained by the insertion of individual-level variables.

Focusing on the other dependent variable, well-being (Table 9.1), Model 1 indicates the importance of several individual-level variables. The strongest impact is found for the variables social support and economic hardship. The first variable is related to an increase in well-being and the other to a decrease of it. Other important variables are somatic complaints (reducing well-being) and work–life balance (increasing well-being). Furthermore, both influence in the work situation and work demands have impact in expected directions. Occupational category is also an important variable, although less expected. Managers and professional categories have considerably lower well-being than manual workers. There are also small effects of gender and age.

Both job insecurity and employment security have an impact on well-being in expected directions. Job insecurity decreases well-being while employment security works in the other direction. This means that if an employee finds opportunities in the labor market, the negative effects of job insecurity on well-being may be reduced. It is important to emphasize that this model includes many important factors behind well-being, for example, the somatic status of the respondent. The variables measuring security and insecurity, therefore, withstand a rather hard test and still show unique effects on well-being.

As for variation in coefficients among countries, only gender and occupational category do not display significant country-level variance. In general, however, less variation in well-being (5 %) is due to differences among countries compared to the previous analysis (see null model). Furthermore, much of this variation is a compositional effect – approximately 77 % is explained by the individual-level variables controlled for in Model 1. This implies that there is not much variance left to explain by country-level variables. However, one has to consider that the countries studied here are rather affluent in a global perspective, and more country-level variation would most certainly appear if less rich countries had been included.

3.2 Country-Level Factors

We now turn to the significance of the country-level variables – the strictness of employment protection legislation (EPL), the investments in passive and active labor market policies, and the general unemployment level in the countries. Table 9.2 shows the results for both job insecurity and well-being. Focusing first on job insecurity, Model 2 shows the impact of each of the variables separately but with control for the individual-level variables. Both unemployment level and investments in ALMPs are statistically significant and related to an increase respectively a decrease to the level of job insecurity in the country. For example, if the unemployment level increases five percentage points, the predicted rise in general perceptions of job insecurity (the country-level intercept in the analysis) will be 0.22 on a 0–4 scale.

In Models 3 and 4, the country-level variables are analyzed together within the same model. However, PLMPs and ALMPs are analyzed separately because of very high internal correlation. In Model 3, PLMPs are statistically significant beside the unemployment rate. It implies a reduced level of job insecurity with increased expenditures of PLMPs. This relationship, however, only appears under control of the unemployment rate, which can be explained by a correlation between unemployment level and spending on PLMPs. When this correlation is controlled for, a unique effect of PLMPs appears which probably has to do with the generosity of the benefits. The significance of ALMPs still remains in Model 4, indicating that investment in ALMPs is also related to decreased levels of job insecurity.

Focusing on well-being, statistically significant relationships are found to both PLMPs and ALMPs, but not to EPL and the unemployment rate. And both coefficients go in the same direction: spending on labor market policies are related to increased levels of well-being in the countries.

3.3 Cross-Level Interactions

The last step of the analysis is to check whether any of the country-level variables affect the impact of individual-level variables on job insecurity and well-being (so-called cross-level interactions). Following the theoretical considerations, three variables on the individual level are in focus: employment security, employment contract, and job insecurity – the last variable only in relation to well-being. The results are presented in Table 9.3.

Focusing on job insecurity, interactions were found for two of the institutional variables. Model 5 shows the interaction between employment protection legislation (EPL) and employment security. It indicates that the negative impact of employment security – employees’ perceived possibilities to find another job in the labor market – on job insecurity is reduced, the stricter the employment protection. In substance, this implies that employment security does not reduce job insecurity so much in countries with strict EPL, but is very important in countries with liberal labor legislation.

As for temporary contracts, we expected that the strictness of EPL would increase the effect of temporary contracts on job insecurity. The results in Model 6 confirm this expectation. However, a less expected result is that investments in ALMP also seem to add to the difference between permanent and temporary employees with respect to job insecurity (Model 7). In Model 8, all the interactions are analyzed together in the same model. The results are still valid.

We continue with the other dependent variable – well-being – where interaction effects are also revealed. Investment in labor market policies, especially in PLMPs, reduces the negative effect of job insecurity on well-being. A possible interpretation is that a generous UI makes the risk of unemployment less of a stressor for employees.

4 Concluding Discussion

In today’s globalized markets, companies and organizations seem to strive for flexibility, that is, to be able to change production in relation to upturns and downturns, consumer preferences and technological innovations. Every hindrance to flexibility is believed to affect companies negatively in the global competition, and politically one can find a pressure to abolish these obstacles, for example, by deregulating employment protection legislation.

Even though flexibility may boost economic activity, a possible side effect is the appearance of labor markets with increased levels of job insecurity. Employees’ uncertainty of the continuance of their job can grow in a situation of change where competencies soon becomes obsolete and employers constantly adjust the size of their staff to the demand for their products. And as is well known, job insecurity of employees can have adverse health effects. The quest for flexibility may therefore be accompanied by a cost of decreased well-being.

However, research has shown that the negative consequences of insecurity and uncertainty can be mitigated if the individual can find strategies to cope with the insecure situation. The focus in this chapter has been on a policy proposal – flexicurity – that emphasizes the importance of creating an institutional setting around the labor market which gives individuals the resources to cope with flexibility.

The proponents of flexicurity believe that a flexible labor market with low job protection should be combined with passive and active labor market policies that make transitions between jobs more secure. Passive measures have to do with a generous unemployment insurance, and active measures to help the unemployed to come back to work. They argue that spending on these kinds of measures is a reasonable way to find a compromise between flexibility and security that employers and employees can agree upon. In this chapter, we have examined how the institutions emphasized in the flexicurity discourse work in relation to employees’ experiences of job insecurity and well-being.

The findings from the present study have significance for the evaluation of the flexicurity proposal. First of all, no statistically significant relationship was found between the strictness of the employment protection legislation (EPL) and job insecurity or well-being. This result can be regarded to be in line with the flexicurity formula by downplaying the role of EPL for employees’ perceptions of job insecurity and well-being. Furthermore, the analysis reveals a side effect of employment protection legislation, in that temporary employees with insecure jobs may experience even more insecurity, the stricter the EPL. This implies that strict EPL may lead to labor market dualization with a secure centre of protected jobs and an insecure periphery of temporaries unsheltered from labor market flexibility.

However, the analysis also shows that employment security – the security of having options in the external labor market to find another job – becomes more important in situations with liberal rather than strict EPL to reduce insecurity. Employment security is therefore an important compensational mechanism if the EPL is reduced. A similar effect is found also in Berglund et al. (2014) in an analysis of Swedish data where the effect of cognitive job insecurity (the assessed risk of losing a job) on affective job insecurity is reduced in the presence and increased in the absence of employment security. These results seem to give credit to the critics who believe flexicurity – or, more specifically, reduced EPL to achieve flexibility – is not for “bad weather” (Tangien 2010).

Flexicurity is not only about flexibility but also about increased levels of security, especially in the form of unemployment insurance. The results of the present study are quite clear concerning expenditures of PLMP and ALMP for the level of job insecurity and well-being. High spending in these regards is related to decreased levels of job insecurity and increased levels of well-being. Furthermore, the results indicate that investment decreases the significance of job insecurity on well-being. High spending seems therefore to compensate for the risk of job insecurity. This result is clearly in line with the flexicurity suggestion that generous welfare provisions and active labor market measures increase the security for employees.

To summarize, this study provides some evidence that the flexicurity proposal may constitute a reasonable trade-off for employees in respect of possible effects on job insecurity and well-being. Firstly, the results indicate no relationship between liberal employment protection legislation and high levels of job insecurity or reduced well-being. Flexibility in the labor market may therefore not necessarily imply these kinds of negative effects, although a flourishing labor market seems to be an important ingredient to escape negative effects of low job protection. Secondly, of great importance in the flexicurity formula is spending on welfare provisions, especially unemployment benefits. These measures affect both job insecurity and well-being in favorable directions.

This chapter has focused especially on the flexicurity proposal which has been marketed by its advocates as a way to reconcile flexibility and security in European societies. There are also other suggestions in the discussion as to how this should be done. Life-long learning and social investment in the employability of the work force are important perspectives, emphasizing the importance of education and opportunities to re-learn during the life-course (Forrier and Sels 2003; Morel et al. 2012). The way to secure employment is therefore to create resources for the individual to adapt to what is demanded in the labor market (Schmid 2008). The school system is vital here, and in particular, adult education. However, these policy proposals come many times hand-in-hand with a normative pressure on the individual to be “employable” (Garsten and Jacobsson 2004). Flexicurity is not incompatible with these perspectives. The opportunities for training are one central aspect of the active labor market policies emphasized and are in line with the employability paradigm. Furthermore, when the Danish example is presented, many times this model is described as a “Golden Square” rather than a “Golden Triangle” by also including the country’s very well-developed adult education in the model.

However, a general criticism against the flexicurity proposal that is possible to make is that it only emphasizes the economic or financial aspects of a job. If a job is lost, flexicurity focuses on how the income it generates should be replaced – either by fast finding a new job, or by getting compensation from unemployment insurance. In the perspective of flexicurity, job insecurity seems therefore mainly to be a function of the risk of losing income. However, as emphasized in the beginning of this chapter, a job also has latent functions for people (Jahoda 1982). It is an important source for finding meaning, structure, and social belongingness in life. Losing a job that is meaningful and satisfying, and in which one has developed deep-seated social relations to workmates is to be considered as a great loss. Sometimes, a job loss may imply that one has to move geographically to find a new and leave an established social community. Perhaps one can say, in line with the concepts of Mark Granovetter (1983), that flexicurity presupposes an individual with rather weak social ties but with a large network of contacts, who is prepared to leave for new challenges. Such individuals stand in stark contrast to employees less mobile, but still developing strong ties to the workplace and the local community. For these people, job insecurity represents a severe threat to who they are and where they belong.

In closing this chapter, a last and important question to ask is what chance flexicurity has in today’s political climate to be a realistic policy proposal. In times of crises and austerity, flexicurity may not fall on fertile ground. Denmark, the flexicurity country par excellence, is one of the OECD countries that spent most on labor market policies (in 2011, 3.91 % of GDP, in first place out of 28 OECD countries).Footnote 2 And in the wake of the financial and Euro crises with rising unemployment figures, Denmark has started to reduce the generosity of the unemployment insurance by cutting back the maximum duration of benefits from 4 to 2 years (Madsen 2011). Furthermore, central actors in the management of the European crises, for example, the so-called Troika, have pressed countries, especially in Southern Europe, to make labor market reforms in the direction of flexibilization (Bieling 2012; Clauwaert and Schömann 2012). According to the insights of the present study, such reforms may be very risky for employees unless they are accompanied by massive investments in passive and active labor market policies. However, this seems rather unlikely in the presence of large deficits in national budgets. A less glimmering future prospect for European labor markets is therefore flexibility without security.

Notes

- 1.

For more information: http://eurofound.europa.eu/ewco/surveys/

- 2.

OECD (2010), “Labour market programmes: expenditure and participants,” OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database). doi: 10.1787/data-00312-en (accessed 29 January 2014).

References

Anderson, C. J., & Pontusson, J. (2007). Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research, 46, 211–235.

Bengtsson, M., & Berglund, T. (2012). Labour market policies in transition: From social engineering to stand-by-ability. In B. Larsson, M. Letell, & H. Thörn (Eds.), Transformations of the Swedish welfare state: From social engineering to governance? (pp. 86–103). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berglund, T., Aho, S., Furåker, B., Lovén, K., Madsen, P. K., Nergaard, K., Rasmussen, S., Svalund, J., & Virjo, I. (2010). Labour market mobility in Nordic welfare states. TemaNord 2010: 515. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

Berglund, T., Furåker, B., & Vulkan, P. (2014). Is job insecurity compensated for by employment and income security? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 35(1), 159–178.

Bieling, H.-J. (2012). EU facing the crisis: Social and employment policies in times of tight budgets. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 18(3), 255–271.

Bonoli, G. (2010). The political economy of active labor-market policy. Politics & Society, 38(4), 435–457.

Borg, I., & Elizur, D. (1992). Job insecurity: Correlates, moderators and measurement. International Journal of Manpower, 13(2), 13–26.

Bredgaard, T., Larsen, F., & Madsen, P. K. (2005). The flexible Danish labour market – A review. CARMA research papers 2005:01. Aalborg: Aalborg University.

Cheng, G. H.-L., & Chan, D. K.-S. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 272–303.

Chung, H., & Van Oorschot, W. (2011). Institutions versus market forces: Explaining the employment insecurity of European individuals during (the beginning of) the financial crisis. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(4), 287–301.

Clauwaert, S., & Schömann, I. (2012). The crisis and national labour law reforms: A mapping exercise. Working paper 2012.04, ETUI.

De Cuyper, N. D., Bernard-Oettel, C., Berntson, E. D., Witte, H., & Alarco, B. (2008). Employability and employees’ well-being: Mediation by job insecurity. Applied Psychology, 57(3), 488–509.

De Witte, H. (2005). Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4), 1–6.

Dickerson, A., & Green, F. (2012). Fears and realisations of employment insecurity. Labour Economics, 19(2), 198–210.

Erlinghagen, M. (2008). Self-perceived job insecurity and social context: A multi-level analysis of 17 European countries. European Sociological Review, 24(2), 183–197.

Esser, I., & Olsen, K. (2012). Perceived job quality: Autonomy and job security within a multi-level framework. European Sociological Review, 28(4), 443–454.

Eurofound. (2010). Sampling implementation report. 5th European working conditions survey, 2010.

European Commission. (2007). Towards common principles of flexicurity: More and better jobs through flexibility and security. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2003). The concept of employability: A complex mosaic. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3(2), 102–124.

Garsten, C., & Jacobsson, K. (Eds.). (2004). Learning to be employable. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233.

Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Towards conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 438–448.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Huang, G.-H., Lee, C., Ashford, S., Chen, Z., & Ren, X. (2010). Affective job insecurity: A mediator of cognitive job insecurity and employee outcomes relationships. International Studies of Management & Organizations, 40(1), 20–39.

Jahoda, M. (1982). Employment and unemployment. A socio-psychological analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jørgensen, H., & Madsen, P. K. (Eds.). (2007). Flexicurity and beyond. Finding a new agenda for the European social model. Copenhagen: DJØF Publishing.

Layard, R., Nickell, S., & Jackman, R. (1991). Unemployment: Macroeconomic performance and the labour market. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lindvall, J. (2010). Mass unemployment and the state. Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: January 2011. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199590643.001.0001.

Madsen, P. K. (2011). EEO review: Adapting unemployment benefit systems to the economic cycle, 2011. European Employment Observatory. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

McDowell, I. (2010). Measures of self-perceived well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69, 69–79.

Morel, N., Palier, B., & Palme, J. (2012). Beyond the welfare state as we knew it? In N. Morel, B. Palier, & J. Palme (Eds.), Towards a social investment state? Ideas, policies and challenges. Chicago: The Polity Press.

Näswall, K., & DeWitte, H. (2003). Who feels insecure in Europe? Predicting job insecurity from background variables. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 24(2), 189–215.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

OECD. (2004). Employment outlook. Paris.

OECD. (2010). Employment outlook 2010 – Moving beyond the job crises. Paris.

Sapir, A. (2006). Globalization and the reform of European social models. Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(2), 369–390.

Schmid, G. (2008). Full employment in Europe. Managing labour market transitions and risks. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Sjöberg, O. (2010). Social insurance as a collective resource: Unemployment benefits, job insecurity and subjective well-being in a comparative perspective. Social Forces, 88(3), 1281–1304.

Skedinger, P. (2008). Effekter av anställningsskydd. Vad säger forskningen? Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 242–264.

Tangian, A. (2010). Not for bad weather: Flexicurity challenged by the crisis. ETUI Policy Brief, Issue 3, Brussels.

Venn, D. (2009). Legislation, collective bargaining and enforcement: Updating the OECD employment protection indicators (OECD social, employment and migration working papers, no. 89). OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/223334316804

Vulkan, P. (2012). Labour market insecurity: The effects of job, employment and income insecurity on the mental well-being of employees. Revista Internacional de Organizaciones, 9, 169–188.

Wilthagen, T. (1998). Flexicurity: A new paradigm for labour market policy reform (Discussion paper FS-I 98-202). Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum.

Wilthagen, T., & Tros, F. (2004). The concept of “flexicurity”: A new approach to regulating employment and labour markets. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 10(2), 166–187.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Berglund, T. (2015). Flexicurity, Job Insecurity, and Well-Being in European Labor Markets. In: Vuori, J., Blonk, R., Price, R. (eds) Sustainable Working Lives. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9798-6_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9798-6_9

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9797-9

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9798-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)