Abstract

Children’s friendships are closely associated with children’s positive well-being. Children who enjoy close friendships are more likely to experience higher levels of happiness, life satisfaction and self-esteem and less likely to be lonely, depressed or victimized. Friendships during childhood are predictive of greater self worth and coping skills later in life but the direction of the relationship between children’s well-being and their friendships (i.e., whether well-being is a cause or consequence of friendships) is not firmly established. Though the study of the links between children’s happiness and friendships is relatively sparse, recent developments in measures of children’s well-being are encouraging. This is important because the relationship between friendships and well-being may be different for children compared to adults and adolescents for reasons such as children do not typically have mature romantic relationships but they do experience friendships with imaginary companions. Given the unique importance of children’s friendships in understanding and promoting children’s happiness, we outline several considerations for future studies in this promising area of research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The association between children’s well-being and their friendships is important. The establishment of intimate friendships begins in childhood and comprises an important landmark in development. During childhood, children typically experience a transition where they spend less time with their parents and more time with their peers (Collins and Russell 1991). It is during childhood that stable friendships develop, and these friendships are less transient and superficial than those experienced at younger ages (Edwards et al. 2006). Children’s capacities for high levels of trust and self-disclosure develop in their friendships. Children who enjoy good friendships also experience benefits such as better capacity to cope with stress (Berndt and Keefe 1995), a lower incidence of being victimized (McDonald et al. 2010) and being rejected by peers (Schwartz et al. 2000), greater self-esteem and prosocial behaviors, and less loneliness and depression (Burk and Laursen 2005; Hartup and Stevens 1999).

Importantly, children’s friendships have an enduring impact. The choices children make and the experiences they have within their friendships play an important role in children learning the rules that govern social interactions. This learning impacts their future development (Howes and Aikins 2002). Children who experience friendships have higher self-worth as young adults (Bagwell et al. 1998) and enjoy better success in academics and better adjustment to school (Ladd 1990; Wentzel et al. 2004). In contrast, children with few friends and weak peer relations are more likely to experience difficulties in life status, perceived competence and mental health as adults (Bagwell et al. 1998; Cowen et al. 1973). If we are to develop a more comprehensive understanding of normative development and well-being in children, then we need to research children’s friendships.

Given that friendships are consistently found to be associated with children’s current well-being and their later development, the present chapter has four main goals. First, we provide a brief summary of the literature on the links between positive well-being and social relationships, particularly friendships. Second, we summarize work on the assessment of happiness, life satisfaction and friendships in children. Third, we discuss the literature on children’s happiness and their friendships, including their friendships with imaginary companions. Finally, we use our literature review to provide guidance for future research on children’s happiness and friendships.

Over the last century a substantial amount of literature on the qualities and characteristics of children’s friendships has been gathered (Berndt 2004; Bukowski et al. 2011; Ladd 2009; Rubin et al. 2011). Much of the early research focused on understanding how children selected their friends (e.g., child-peer proximity) and identifying features of children’s friendships. More recently, the emphasis on selection and identification has given way to examining friendships in terms of interpersonal interactions with peer groups (Bukowski et al. 2011; Ladd 2009) and assessing the negative and positive aspects of friendships (Berndt 2004; Goswami 2009; Holder and Coleman 2009). The negative aspects (e.g., conflict, distress and rejection) are inclined to decrease children’s well-being (e.g., increase depression and loneliness) and adjustment (e.g., poor academic performance), which may extend into adulthood (Bukowski et al. 2011; Ladd 2009). The positive aspects of friendships tend to promote stable psychological functioning (e.g., increased security and affection) and adjustment (e.g., aiding sociability, and conflict resolution) in children (Berndt 2004; Bukowski et al. 2011; Majors 2012; Moore and Keyes 2003; Rubin et al. 2011).

Good friendships provide benefits such as companionship, sociability, feelings of self-worth, emotional security, affection, and well-being (Berndt 2004; Rubin et al. 2011). Research has described children’s well-being in terms of factors that prevent negative, or promote positive, behaviors (Moore and Keyes 2003). Both positive well-being and good friendships promote self-worth, sociability, character, and affection. The extant literature supports the idea that positive aspects of friendship serve to complement children’s happiness, while negative aspects diminish children’s happiness (Goswami 2012; Holder and Coleman 2009).

Understanding the role of friendships in children’s well-being is limited because most of the research on relationships and well-being is based on samples drawn from populations of adults and adolescents, not children. As an illustration of this, in the book “Understanding Peer Influence in Children and Adolescents”, the words “adolescent” and “adolescence” appear in five of the eleven chapter titles but “Child”, “Children” and “Childhood” do not appear in any (Prinstein and Dodge 2008). In fact, though the index lists six entries for “adolescent peer influence” there are no entries for “children”. Studies of adolescents indicate that their well-being is associated with social relationships. For example, 16–18 year olds who report high levels of success in their social relationships, including in their relationships with peers, also report the highest levels of life satisfaction (Proctor et al. 2010). However, research on the relationship between positive well-being and personal relationships including friendships is incomplete in preadolescent children.

This incompleteness stems in part from a bias in research to focus on ill-being. Many fields of research including psychology, psychiatry, neuroscience and medicine, emphasize the diagnosis and treatment of illness and dysfunction. This emphasis has clearly paid dividends as it has led to evidence-based tools and interventions to identify and help people with physical and psychological challenges. However, a newly emerging field, positive psychology, purports that the elimination of illness and dysfunction does not exhaust the goals of science. Positive psychology recognizes the value in diagnosis and treatment of negative conditions, but contends that research should also focus on understanding and promoting strengths and positive subjective well-being.

There is a consensus in positive psychology that our interpersonal relationships are strongly linked to our positive well-being. Though the direction of this link is not firmly established, it has been assumed that relationships promote our well-being. Correlational research is consistent with this assumption. For example, in all but one of the seventeen countries investigated, people who were married were happier even after sociodemographic variables were controlled (Stack and Eshelman 1998). Research has demonstrated that romantic relationships of high quality contribute to happiness over and above the influence of personality (Demir 2008), and married individuals report higher levels of happiness than those who are single (never married), divorced, separated (Dush et al. 2008; Proulx et al. 2007) or cohabiting (Stack and Eshleman 1998).

The links between well-being and social relationships include relationships with friends. For example, best friends are predictive of an individual’s happiness (Demir et al. 2007). Individual studies report that the number of friends one has (Burt 1987; Lee and Ishii-Kuntz 1987; Requena 1995), and the quality of one’s friendships (Demir et al. 2013) are positively correlated with one’s happiness, with the correlations involving quality typically being higher. A meta-analysis similarly concluded that the quantity and quality of friendships are associated with subjective well-being with the associations involving quality being stronger, though this study focused on the elderly (Pinquart and Sörenson 2000).

It is possible that friendships contribute to happiness because friendships help ensure that there is an environment where people can feel safe while engaging in their preferred behaviors and where people perceive that their basic psychological needs are being met. Evolutionary-based theories suggest that positive social relationships should contribute to well-being; we are motivated throughout life by a drive to develop and maintain enduring, positive, social relationships (Baumeister and Leary 1995).

The contribution of friendships to children’s well-being may differ from adolescents’ and adults’ because children are at a different level of development with respect to emotions, temperament/personality, and maturity than older populations. At least three factors support the contention that the relationship between well-being and friendships may differ for children. First, preadolescent children do not typically have well-developed romantic relationships. The impact of friendships on well-being for adults and adolescents is influenced by their romantic relationships. For example, for those people who do not have a romantic partner, the quality of one’s relationship with their best friend and mother predicts their happiness (Demir 2010). However, friendships are no longer predictive of happiness for those people who do have a romantic partner. Given that children do not typically experience the romantic relationships that adolescents and adults experience, perhaps the importance of friendships to their well-being is magnified. Second, children often have relationships with imaginary companions. These “friendships” may influence children’s well-being in unique ways. Third, throughout the life cycle, friendship can be qualitatively different in terms of significance and purpose as well as the distinct social needs they fulfill (see Majors 2012).

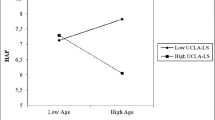

In addition to the possibility that the contribution of friendships to happiness may differ between adults, adolescents and children, their contribution may differ for children of different ages. For example, as children age their friendships become increasingly important as a source of happiness and their relationships with their parents become less important (Thoilliez 2011). Additionally, the components of friendships (instrumental support, positive affect, trust and fairness) mature and change as children age. However, even young children recognize that friendships are valuable contributors to their happiness, and that being alone, even when with toys, is not a strong source of happiness (Thoilliez 2011).

However, the causal direction of the relationship between friendships and well-being may not be limited to friendships causing increases in well-being. Research suggests that the link between well-being and social relationships is bidirectional; high levels of well-being can be both the cause and consequence of the quality and quantity of our social relationships. Empirical work supports the idea that well-being can promote social relationships For example, high levels of present happiness predict a greater likelihood of future marriage (and a lower likelihood of divorce), and predict a larger circle of friends and increased social support (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a; Lyubomirsky et al. 2005b). Well-being may also promote friendships. Both longitudinal and experimental designs indicate that positive well-being increases social interactions (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a).

The current chapter reviews the extant literature on the relations between children’s well-being and aspects of their social relationships. We begin by reviewing how researchers have assessed happiness, life satisfaction and social relationships in children. We then focus on the connection between well-being and aspects of children’s friendships including popularity and imaginary friends. Synthesizing this literature allowed us to identify future considerations and directions for research on children’s friendships and well-being.

Assessment of Well-Being and Friendships in Children

Though even very young children recognize and understand emotions including happiness (Harter 1982), research on children’s happiness is limited (Holder 2012). The development of valid and sensitive measures of positive well-being has progressed more slowly in children than adults, and more slowly than measures of ill-being in children. This slower development may have contributed to the relatively few studies of children’s positive well-being (Huebner and Diener 2008).

However, this slower development has been addressed with work on assessing life satisfaction (Huebner 1991, 1994), affect (Laurent et al. 1999), gratitude (Froh et al. 2011) and hope (Snyder et al. 1997) in children. One of the best examples of the successful development of psychometrically-sound measures of well-being in children is the assessment of life satisfaction. Assessing life satisfaction in children owes a debt to the seminal work of Diener et al. (1985) who developed The Satisfaction with Life Scale for adults. Using this scale as a starting point, unidimensional (Huebner 1991) and multidimensional (Huebner 1994) scales of life satisfaction have been developed. The unidimensional measure is comprised of items that are not specific to any single context whereas the multidimensional scale asks students to rate their life satisfaction in each of five contexts: family, friends, self, school and living environments.

Measuring well-being in children will certainly benefit from instruments designed to assess adults. For example, scales designed to assess gratitude in adults show a similar factor structure when used with children (Froh et al. 2011). However, these instruments may not all be well suited to assessing children. For example, different gratitude scales are well correlated for adolescents and adults, but not necessarily for children. Furthermore, negative affect and gratitude are correlated with adolescents and adult samples, but they are not strongly correlated with younger children. Additionally, not all items on adult gratitude scales appear to assess gratitude in children. As a result, though some scales seem to apply across a wide age range of children and adolescents (e.g., Children’s Hope Scale; Snyder et al. 1997), other scales may not be valid with younger children (e.g., scales assessing gratitude).

Assessing well-being in children requires more than simply ensuring that the reading level of the measures is appropriate. During childhood there are significant and relevant individual differences in cognitive development (Berk 2007). As a result, some children’s development of formal operations may be lagging resulting in them not possessing sufficient abstract thinking to allow them to engage in the self reflection required by the measures. As a result, scales to assess well-being might have to be developed specifically for children, and in addition to self-reports, parent-reports may be valuable.

To assess happiness in children, researchers have relied on a variety of measures including single item measures where the response options are more intuitively represented as faces ranging from sad to happy (Holder and Coleman 2009) and as a stair case where higher steps represent increased happiness (Jover and Thoilliez 2010). These scales are attractive because they are effective with children who have limited reading skills and with children from different cultures (Holder 2012). These single-item self-report measures can be effectively combined with multi-item measures designed for children (e.g., Piers-Harris Self Concept Scale for Children Second Edition) and adults (Subjective Happiness Scale) and parent reports, both in specific contexts (e.g., school and home) and overall. We are more confident in our findings regarding children’s relationships and well-being because the conclusions reached with each quantitative measure are similar (Holder and Coleman 2009). Furthermore, studies that rely on biographical data (children’s story-telling about their own lives) also reach similar conclusions about the importance of friendships in children’s happiness (Thoilliez 2011).

To assess aspects of friendships in children, many studies have developed their own scales. As a result, it may be challenging to compare the findings between studies. Huebner (1994) developed the Multidimensional Students’ Life Scale which includes a friendship domain scale consisting of 9 items. This scale has proven valuable in investigating the relations between well-being and friendships in children. More recently, an additional item was added to this domain scale (“I feel safe with my friends”) and this scale has been used successfully to assesses both the positive (“My friends are great”) and the negative (“My friends are mean to me”) aspects of children’s friendships (Goswami 2012). However, whether studies use questionnaires to quantify aspects of children’s friendships and their importance (Holder and Coleman 2009; Huebner 1994), or rely on more autobiographical stories (Thoilliez 2011), the findings all point to the important contribution of children’s friendships to their happiness.

Personal Relationships and Well-Being

Friendship can be viewed as a mutual relationship that exists between two persons whose intentions are to help meet the physical and psychological needs of their partner. The quality of adult friendships appears to influence happiness, even beyond the influence of personality (Demir and Weitekamp 2007). Extraverted adolescents who were very happy were also more likely to have strong interpersonal relationships and rarely spent time alone (Cheng and Furnham 2001; Diener and Seligman 2002). The strength of the mutual companionship between friends may also influence happiness. Lyubomirsky et al. (2006) suggest that the positive feelings of closeness and satisfaction that exists between friends are important to personal happiness.

Friendships are also associated with the well-being of children. Positive engagement with a peer may teach children healthy ways to engage with others, to manage conflict, and to problem solve, thus allowing them to more effectively work through and maintain their interpersonal relationships (Newcomb and Bagwell 1995; Majors 2012). Positive social adjustments made with friends and peers in early and middle childhood are potentially beneficial to the developing child’s academic performance (Ladd et al. 1996). However, the majority of empirical research examines the interpersonal relationships and well-being of adolescents and adults (e.g., Argyle 2001; Demir 2010; Demir and Özdemir 2010, Diener et al. 1995; Diener and Seligman 2002). More research is required to fully understand the relationships between friendships and positive and negative emotions during early and middle childhood.

To help address this gap in the literature, Holder and Coleman (2009) assessed 9–12 year old children and identified several factors related to friendship that are associated with children’s well-being (i.e., number of friends and time spent with friends outside of school). Recently Goswami (2012) expanded on our research using a large sample (n = 4673) of children and young adolescents. He reported that of the six types of social relations assessed, the positive aspects of children’s friendships were the second most closely associated with children’s happiness (after relationships with family).

All dimensions of children’s social relationships are not positive. Even happy children are likely to be exposed to conflict and distress within their relationships with family and friends. This conflict and distress plays a significant negative role in determining the well-being of adults and children (e.g., Ben-Ami and Baker 2012; Gerstein et al. 2009). A child’s negative interactions with others during early and middle childhood may leave the child at greater risk for social maladjustments or mental illness in their later adolescence or adulthood (Bagwell et al. 1998; Majors 2012). Poor social interactions may also negatively impact children’s happiness. Holder and Coleman (2009) examined the relationships between behaving badly towards others and children’s happiness. They found that several undesirable social interactions between childhood peers (e.g., being mean to others, unpopular, picked on, and left out) were negatively correlated with children’s happiness. Qualitative work is consistent with these findings in that it also shows that negative interactions with friends (e.g., rejection and disapproval) are recognized by children as eroding their happiness (Thoilliez 2011). Overall, these results suggest that negative social relationships have an adverse effect on children’s happiness. Goswami (2012) reported similar findings in that negative relations with friends were associated with lower levels of well-being though this link was not as strong as with positive relations.

Research investigating the relationship between happiness and friendship in children has largely relied on correlational methods. The findings are consistent with the view that children’s friendships can influence their happiness. This view is reflected in children’s assessment of the contribution of friendships to their own happiness. Children, particularly those who are least happy, identify having more friends as a key factor in increasing their happiness (Uusitalo-Malmivaara 2012). Furthermore, using qualitative research methodology, Thoilliez (2011) found that after the family, friendships and peer relationships were identified by children as the most important contributors to their happiness. However, given the limits of correlational research, these results are also consistent with the perspective that happy children are more likely to engage in positive social relationships, which is consistent with research that suggests that happiness precedes desirable outcomes (e.g., Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a; Strayer 1980).

Family members are important to the learning and development of interpersonal relationships and friendships (Majors 2012; Mendelson and Aboud 1999). Theorists suggest that several basic components of social relationships (e.g., power, conflict, and quality) influence the development of healthy relations with others (Demir 2010; Furman and Buhrmester 1985; Wiggins 1979). These components are also important to the development of social adjustment, respect, performance, communication, self-worth, nurturance, guidance, and psychological well-being (Furman and Buhrmester 1985; Ladd et al. 1996; O’Brien and Mosco 2012). For instance, the configuration of power within a friendship that exists between a child and their siblings and parents appears to have a significant role in the child’s well-being (Furman and Buhrmester 1985). Children’s relationships with their equals (i.e., with their peers and siblings) are associated with more power and greater well-being for these children, than their relationships with adult authority figures such as their parents or teachers (Furman and Buhrmester 1985). However, the power configuration for children in friendships with their siblings and peers can also contribute to more conflict, thus reducing happiness and increasing discordance within the friendship.

More friendships are indicative of greater popularity. However, research has not provided a clear consensus on the direction and strength of the association between popularity and well-being for either adults or children. For children, an increase in their own status relative to their peers is associated with higher levels of well-being (Ostberg 2003). Nevertheless, undergraduates were shown to be less happy if they placed a high value on popularity and personal image (Kasser and Ahuvia 2002). This suggests that being popular and valuing popularity are not the same and these dimensions, which are linked to friendships, could influence well-being in different directions.

Research has shown that popularity and happiness share similar correlates. For example, higher levels of either happiness or popularity are associated with lower levels of suicidal ideation in adolescents (Field et al. 2001), and bullying behavior in children (Slee 1993). In our own research, we found that several measures of children’s happiness were only weakly positively correlated with popularity (Holder and Coleman 2008). Collectively, the data suggest that popularity contributes only modestly to children’s happiness. Children seem to recognize this. When asked to choose from a list of 12 factors potentially related to their happiness, 12 year old children identified “Becoming a celebrity” as the least likely factor to increase their happiness (Uusitalo-Malmivaara 2012).

Children’s friendships are not limited to actual friends but may include imagined or pretend friends as well. Many children have invisible friends. Some research suggests that by the time children reach the age of seven, approximately 37 % have an invisible friend (Taylor et al. 2004) and overall approximately 65 % of children have an imagined companion (Singer and Singer 1990; Taylor et al. 2004). However, other research suggests that the percentage is much less (26 %; Gleason and Hohmann 2006). Imaginary companions can include invisible friends as well as objects (e.g., a teddy bear) that are personified (Bouldin and Pratt 2001; Hoff 2005a, 2005b; Taylor et al. 1993). Invisible friends are similar to real friends in that they can be seen, heard and felt by the children (Taylor et al. 2009), and the activities that children share with their invisible friends are similar to real friendships including playing, arguing and joking (Taylor et al. 2009). Relationships with imaginary friends are long lasting (Partington and Grant 1984) and are viewed by children as at least as important as those with real friends (Mauro 1991). Imaginary friends may play important roles in helping children cope with a missing family member (Ames and Learned 1946), and providing nurturance (Gleason 2002), sympathy and understanding (Vostrovsky 1895).

Having imaginary companions has benefits that may contribute to children’s positive well-being. For example, imaginary friends may offer company to children who are lonely or are challenged in developing relationships with real friends (Manosevitz et al. 1973). Additionally, compared to children who do not have imaginary friends, those with imaginary friends are less shy (Mauro 1991) and experience less fear and anxiety in social situations (Singer and Singer 1981). Children with imaginary friends smile and laugh more during interpersonal relations (Singer and Singer 1981) which is consistent with the idea that imaginary friends contribute to well-being. At the very least, imaginary friends do not seem to impede the development of real friendships. Compared to children who do not have imaginary friends, children with imaginary friends have similar numbers of reciprocal real friendships (Manosevitz et al. 1973) and are equally likely to be identified as well liked by their peers (Gleason 2004). Furthermore, children with imaginary friends tend to show traits related to extraversion (i.e., they are outgoing and sociable; Taylor et al. 2009). Extraversion in adults is strongly associated with positive well-being (Steel et al. 2008), and temperament traits akin to extraversion are linked to happiness in children (Holder and Klassen 2010). Though children clearly seem to recognize that their imaginary friends are pretend (Taylor et al. 2009), imaginary friends provide very similar benefits to real friends in terms of social provisions (Gleason 2002).

Given that the benefits of imaginary friendships are similar to real friendships, research on the relation between well-being and friendship in children should assess imaginary relationships. Though we think that on balance imaginary friends are likely to contribute to children’s well-being, the contribution may be mixed. Children report that they experience conflicts with their imaginary friends and can feel frightened by and angry with their imaginary friends (Taylor 1999).

Conclusion and Implications for Future Research

Through their research, positive psychologists have reached a consensus that social relationships, including the quality of one’s friendships, are important contributors to well-being (e.g., Demir and Weitekamp 2007). Additionally, participation in activities that enhance well-being often includes a social dimension. For example playing on sports teams is associated with well-being and often involves creating and maintaining friendships (Hills and Argyle 1998), volunteering and belonging to a religious group are linked to well-being and social support (Arygyle 2001, Cohen 2002; Francis et al. 1998), and demonstrating kindness towards others can increase well-being and involves a social component (Otake et al. 2006). Given the established contribution of social relations to adults’ and adolescents’ well-being, it is predictable that early research has shown that social relationships are associated with children’s happiness. As an example, children aged 9–12 years who frequently spent time with their friends were happier than children who did not (Holder and Coleman 2008) and children consider more friends as a source of increased happiness (Jover and Thoilliez 2010).

Research on the association of social relationships to well-being is primarily based on samples drawn from adolescent and adult populations. To fully understand this association, children need to be studied as well. The factors that are important in the relations between children’s friendships and happiness (e.g., quality, power, and conflict) are likely to vary with age. Furthermore, as we have discussed, the characteristics of friendships evolve throughout childhood. Given the value of research on friendships and happiness in children, we encourage researchers to consider the following suggestions in guiding their research.

First, the research methods need to be considered. For example, longitudinal studies are more likely to capture the significant factors related to children’s well-being and friendships than cross-sectional studies. The extant literature is comprised largely of correlational studies. Thus the directionality of the links between children’s happiness and friendships is unclear. Longitudinal work has suggested that it may be more plausible to consider that well-being causes positive social outcomes (Adams 1988). An impressive meta-analyses suggested that longitudinal and experimental work demonstrates that happiness may cause positive social relationships (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005a). However, much of this work samples from populations of adults and the elderly; longitudinal and experimental research exploring the direction of the relationship between children’s friendships and well-being is sparse.

Second, the measures used to assess happiness need to be improved. Many measures of happiness are appropriate for adults and adolescents, and the mere adaptation of these measures to children may be inadequate. Positive psychologists have not agreed on the best measure of happiness or well-being. Researchers frequently rely on subjective measures to assess the happiness of adults, adolescents (e.g., Diener and Seligman 2002; Demir 2010) and children (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi and Hunter 2003; Diener et al. 1995; Holder and Coleman 2008, Holder et al. 2009). Very young children and those with limited language capacities present challenges to researchers’ abilities to validly, reliably and sensitively assess well-being. Future research should develop and test alternative measures. For example, implicit measures of happiness may prove valuable, particularly with very young children. As these implicit measures are developed, they should be refined for assessing different ages. However, attempts to develop implicit measures of happiness have met with limited success (Walker and Schimmack 2008).

Third, the study of the relations between positive well-being and friendship in children requires a more nuanced and less generalized perspective. Researchers need to consider individual differences in the child and the nature of their relationships to develop a fuller and more accurate understanding of the relations between children’s friendships and their well-being. For example, social expectations, gender, age, and quality of friendships may influence the relationship between friendships and well-being. For instance, friendships differ between boys and girls (see Edwards et al. 2006) and friendships that are not positive can promote negative behaviors such as bullying, risk-taking, and antisocial activities (Leather 2009) which may undermine well-being. Additionally, the relationship between friendships and well-being may change depending on how children establish and maintain their friendships (e.g., inside school versus outside school, and in person versus texting or online). For example, at least for adolescents and young adults, the qualities of offline and online friendships differ, particularly when the relationships are new (Chan and Cheng 2004). Based on these considerations, we agree with Gilman and Huebner (2003) that measures that take into account context (e.g., home and school) may provide a more complete appreciation of children’s happiness. The investigation of the relationship between friendships and happiness in children needs to increase in its sophistication by considering interactions with additional mediators and moderators such as age, context, parenting style, and temperament.

Fourth, the impact of culture on the relationship between happiness and children’s friendships needs to be considered. Research has demonstrated that there are cultural differences in students’ well-being related to context (Grob et al. 1996; Park and Huebner 2005) and race differences in life satisfaction (e.g., African American students report lower life satisfaction than Caucasian students; Terry and Huebner 1995). Though simple initial forms of play may be similar across cultures, more complex forms of play with friends can differ between cultures depending in part on how adults value children’s play (Edwards 2000). Given the influence of culture on children’s friendships, including cultural differences in parents’ expectations and values related to their children’s friendships, the development and impact of friendships following immigration may be of interest to researchers. Just as research in psychology generally neglects the vast majority of cultures outside of America with studies of Asians and Africans almost completely lacking (Arnett 2008), research on children’s friendships and happiness needs to broaden the populations of children they sample from. Our own research suggests that though the correlates of children’s happiness are similar across cultures, we have identified important differences in the strength of the correlations and the correlates themselves. For example, temperament traits associated with activity, sociability and shyness (temperament traits akin to extraversion) are associated with happiness in children from Canada and India, but emotionality (a temperament trait akin to neuroticism) is associated with happiness only in children from Canada (Holder et al. 2012; Holder and Klassen 2010).

Fifth, the contribution of imaginary friendships to children’s happiness and life satisfaction still needs to be assessed. This contribution is relatively unique to children’s friendships.

Sixth, systems theory should be applied to the positive domains of children’s lives as well as to their strengths. The application of this theory has been fruitful in understanding the development and interactions between largely negative behaviors such as conduct problems, antisocial behavior, violence and criminality (Dodge et al. 2008). Recent work has applied this approach to more positive aspects of children’s development to show how friendships can serve a protective function against the increase in depression as a result of avoidance of, or exclusion by, peers (Bukowski et al. 2010). Though this work is important in understanding critical outcomes such as resilience, there is a rich potential in applying this approach to understanding thriving and flourishing as well.

Though some traditional perspectives have suggested that children do not form important friendships before the age of 7 or 8, research suggests that younger children also form and maintain significant friendships (Dunn 2004; Meyer and Driscoll 1997). By considering differences in the quality of friendships across childhood, researchers can better understand the critical dimensions of friendships that are associated with children’s well-being. With a more sophisticated understanding, we can then develop and test strategies that enhance children’s well-being on a more individualized basis.

Traditionally, educational psychologists have been primarily concerned with identifying and treating ill-being in children and when these goals are met, their work is considered complete. We agree with other researchers (Huebner and Diener 2008) that identifying and promoting the strengths of children, including enhancing their well-being, is also an important component of work with children. This work needs to include investigations of the relations between children’s happiness and friendships. However, we support the position of researchers who caution against educators and government agencies developing programs that exclusively focus on developing happy children (Thoilliez 2011). With this caution in mind, we recognize that friendship is a key factor in children’s happiness and warrants continued research efforts.

References

Adams, R. G. (1988). Which comes first: Poor psychological well-being or decreased friendship activity? Activities, Adaptation, and Aging, 12, 27–43.

Ames, L. B., & Learned, J. (1946). Imaginary companions and related phenomena. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 69, 147–167.

Argyle, M. (2001). The psychology of happiness (2nd ed.). East Sussex: Routledge.

Arnett, J. J. (2008). The neglected 95 %: Why American psychology needs to become less American, American Psychologist, 63, 602–614. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.602.

Bagwell, C., Newcomb, A., & Bukowski, W. (1998). Preadolescent friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. Child Development, 69, 140–153. doi:10.2307/1132076.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Ben-Ami, N., & Baker, A. J. L. (2012). The long-term correlates of childhood exposure to parental alienation on adult self-sufficiency and well-being. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 40, 169–183. doi:10.1080/01926187.2011.601206.

Berk, L. E. (2007). Child development (7th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Berndt, T. J. (2004). Children’s friendships: Shifts over a half-century in perspectives on their development and their effects. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50, 206–223. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/.

Berndt, T. J., & Keefe, K. (1995). Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustments to school. Child Development, 66, 1312–1329. doi:10.2307/1131649.

Bouldin, P., & Pratt, C. (2001). The ability of the children with imaginary companions to differentiate between fantasy and reality. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 99–114. doi:10.1348/026151001165985.

Bukowski, W. M., Laursen, B., & Hoza, B. (2010). The snowball effect: Friendship moderates the escalations in depressed affect among avoidant and excluded children. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 749–757. doi:10.1017/S095457941000043X.

Bukowski, W. M., Buhrmester, D., & Underwood, M. K. (2011). Peer relations as a developmental context. In M. K. Underwood & L. H. Rosen (Eds.), Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence (pp. 153–179). New York: The Guilford.

Burk, W. J., & Laursen, B. (2005). Adolescent perceptions of friendships and their associations with individual adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 156–164. doi:10.1080/01650250444000342.

Burt, R. S. (1987). A note on strangers, friends, and happiness. Social Networks, 9, 311–331. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(87)90002-5.

Chan, D. K.-S., & Cheng, G. H.-L. (2004). A comparison of offline and online friendship qualities at different stages of relationship development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 305–320. doi:10.1177/0265407504042834.

Cheng, H., & Furnham, A. (2001). Attributional style and personality as predictors of happiness and mental health. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 307–327. doi:10.1023/A:1011824616061.

Cohen, A. B. (2002). The importance of spirituality in well-being for Jews and Christians. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 287–310. doi:10.1023/A:1020656823365.

Collins, W. A., & Russell, G. (1991). Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence.: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review, 11, 99–136. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(91)90004-8.

Cowen, E., Pederson, A., Babgian, H., Izzo, L., & Trost, M. A. (1973). Long-term follow up of early detected vulnerable children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41, 438–446. doi:10.1037/h0035373.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Hunter, J. (2003). Happiness in everyday life: The uses of experience sampling. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 185–199. doi:10.1023/A:1024409732742.

Demir, M. (2008). Sweetheart, you really make me happy: Romantic relationship quality and personality as predictors of happiness among emerging adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 257–277. doi:10.1007/s10902-007-9051-8.

Demir, M. (2010). Close relationships and happiness among emerging adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 293–313. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9141-x.

Demir, M., Orthel, H., & Andelin, A. K. (2013). Friendship and happiness. In S. A. David, I. Boiniwell, & Ayers S. C. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 860–870). Oxford: Oxford Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0063.

Demir, M. & Özdemir, M. (2010). Friendship, need satisfaction, and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 243–259. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9138-5.

Demir, M., Özdemir, M., & Weitekamp, L. (2007). Looking to happy tomorrows with friends: Best and close friendships as they predict happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 243–271. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9025-2.

Demir, M., & Weitekamp, L. A. (2007). I am so happy cause today I found my friend: Friendship and personality and predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 181–211. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9034-1.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13, 81–84. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00415.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 851–864. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.851.

Dodge, K. A., Greenberg, M. T., Malone, P. S., & The Conduct Problems Prevention Group. (2008). Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development, 79, 1907–1927. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x.

Dunn, J. (2004). Children’s friendships. The beginnings of intimacy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Dush C.M., Kamp Taylor M. G., & Kroeger R. A. (2008). Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations, 57, 211–226. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00495.x.

Edwards, C. P. (2000). Children’s play in cross-cultural perspective: A new look at the six culture study. Cross Cultural Research, 34, 318–338. doi:10.1177/106939710003400402.

Edwards, C. P., de Guzman, M. R. T., Brown, J., & Kumru, A. (2006). Children’s social behaviours and peer interactions in diverse cultures. In X Chen, D. C. French, & B. H. Schneider (Eds.), Peer relationships in cultural context (pp. 23–51). New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511499739.002.

Field, T., Diego, M., & Sanders, C. E. (2001). Adolescent suicidal ideation. Adolescence, 36, 795–802. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/.

Francis, L. J., Brown, L. B., Lester, D., & Philipchalk, R. (1998). Happiness as stable extraversion: A cross-cultural examination of the reliability and validity of the Oxford Happiness Inventory among students in the U.K., U.S.A., Australia, and Canada. Personality and Individual Differences, 24, 167–171. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00170-0.

Froh, J. J., Fan, J., Emmons, R. A., Bono, G., Huebner, E. S., & Watkins, P. (2011). Measuring gratitude in youth: Assessing the psychometric properties of adult gratitude scales in children and adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 23, 311–324. doi:10.1037/a0021590.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016.

Gerstein, E. D., Crnic, K. A., Blacher, J., & Baker, B. L. (2009). Resilience and the course of daily parenting stress in families of young children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities Research, 53, 981–997. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01220.x.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, S. (2003). A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 192–205. doi:10.1521/scpq.18.2.192.21858.

Gleason, T. R. (2002). Social provisions of real and imaginary relationships in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 38, 979–992. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.6.979.

Gleason, T. (2004). Imaginary companions and peer acceptance. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 204–209.

Gleason, T. R., & Hohmann, L. M. (2006). Concepts of real and imaginary friendships in early childhood. Social Development, 15, 128–144. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00333.x.

Goswami, H. (2012). Social relationships and children’s subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 107, 575–588. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9864-z.

Grob, A. T., Little, T. D., Warner, B., Wearing, A. J., & Euronet. (1996). Adolescent well-being and perceived control across fourteen sociocultural contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 785–795. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.785.

Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97. doi:10.2307/1129640.

Hartup, W. W., & Stevens, N. (1999). Friendships and adaptation across the life span. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 76–79. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00018.

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (1998). Positive moods derived from leisure and their relationship to happiness and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 523–535. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00082-8.

Hoff, E. V. (2005a). A friend living inside me—the forms and functions of imaginary companions. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 24, 151–189. doi:10.2190/4M9 J-76M2-4Q4Q-8KYT.

Hoff, E. V. (2005b). Imaginary companions, creativity, and self-image in middle childhood. Creativity Research Journal, 17, 167–180. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1702&3_4.

Holder, M. D. (2012). Happiness in children: The measurement, correlates and enhancement of positive subjective well-being in children. Netherlands: Springer Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4414-1_2.

Holder, M. D., & Coleman, B. (2008). The contribution of temperament, popularity, and physical appearance to children's happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 279–302. doi:10.1007/s10902-007-9052-7.

Holder, M. D., & Coleman, B. (2009). The contribution of social relationships to children's happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 329–349. doi:10.1007/s10902-007-9083-0.

Holder, M. D., & Klassen, A. (2010). Temperament and happiness in children. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 419–439. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9149-2.

Holder, M. D., Coleman, B., & Sehn, Z. (2009). The contribution of active and passive leisure to children’s well-being. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 378–386. doi:10.1177/1359105308101676.

Holder, M.D., Coleman, B., & Singh, K. (2012). Temperament and happiness in children in India. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 261–274. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9262-x.

Howes, C., & Aikins, J. W. (2002). Peer relations in the transition to adolescence. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 9, 195–230. doi:10.1016/S0065-2407(02)80055-6.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Students' Life Satisfaction Scale, School Psychology International, 6, 103–111. doi:10.1177/0143034391123010.

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6, 149–158. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.149.

Huebner, E. S., & Diener, C. (2008). Research on life satisfaction of children and youth: Implications for the delivery and school-related services. In M. Eid & R. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 376–392). New York: Guilford Press.

Jover, G., & Thoilliez, B. (2010). Biographical research in childhood studies: Exploring children's voices from a pedagogical perspective. In S. Anderson, I. Denhm, V. Sander, & H. Ziegler (Eds.), Children and the good life: new challenges for research on children (pp. 119–129). London: Springer.

Kasser, T., & Ahuvia, A. (2002). Materialistic values and well-being in business students. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32, 137–146. doi:10.1002/ejsp.85.

Ladd, G. W. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: Predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development, 61, 1081–1100. doi:10.2307/1130877.

Ladd, G. W. (2009). Trends, travails, and turning points in early research on children’s peer relationships. In K. H. Rubin, W. M. Bukowski, & B. Laursen (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 20–41). New York: The Guilford.

Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, B. J., & Coleman, C. C. (1996). Friendship quality as a predictor of young children’s early school adjustment. Child Development, 67, 1103–1118. doi:10.2307/1131882.

Laurent, J., Cantanzaro, J. S., Thomas, J. E., Rudolph, D. K., Potter, K. I., Lambert, et al. (1999). A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment, 11, 326–338. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.326.

Leather, N. (2009) Risk-taking behaviour in adolescence: A literature review. Journal of Child Health Care, 13, 295–304. doi:10.1177/1367493509337443.

Lee, G. R. & Ishii-Kuntz, M. (1987). Social interaction, loneliness, and emotional well-being among the elderly. Research on Aging, 9, 459–482. doi:10.1177/0164027587094001.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005a). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005b). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9, 111–131. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111.

Lyubomirsky, S., Tkach, C., & DiMatteao, M. R. (2006). What are the differences between happiness and self-esteem. Social Indicators Research, 78, 363–404. doi:10.1007/s11205-005-0213-y.

Majors, K. (2012). Friendships: The power of positive alliance. In S. Roffey (Ed.), Positive relationships: Evidence based practice across the world (pp. 127–143). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media B.V. Majors

Manosevitz, M., Prentice, N., & Wilson, F. (1973). Individual and family correlates of imaginary companions in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 8, 72–79. doi:10.1037/h0033834.

Mauro, J. A. (1991). The friend that only I can see: A longitudinal investigation of children’s imaginary companions. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon.

McDonald, K. L., Bowker, J. C., Rubin, K. H., Laursen, B., & Duchene, M. S. (2010). Interactions between rejection sensitivity and supportive relationships in the prediction of adolescent’s internalizing difficulties. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 563–574. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9519-4.

Mendelson, M. J., & Aboud, F. E. (1999). Measuring friendship quality in late adolescents and young adults: McGill friendship questionnaires. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 31, 130–132. doi:10.1037/h0087080.

Meyer, J., & Driscoll, G. (1997). Children and relationship development: Communication strategies in a day care centre. Communications Reports, 10, 75–85. doi:10.1080/08934219709367661.

Moore, K. A., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2003). A brief history of the study of well-being in children and adults. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. M. Keyes, K. A. Moore, & the Centre for Child Well-Being (Eds.), Well-Being: Positive development across the life course (pp. 1–11). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/.

Newcomb, A. F., & Bagwell, C. L. (1995). Children’s friendship relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 306–347. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.306.

O’Brien, K., & Mosco, J. (2012). Positive parent-child relationships. In S. Roffey (Ed.), Positive relationships: Evidence based practice across the world (pp. 91–107), New York: Springer.

Ostberg, V. (2003). Children in classrooms: Peer status, status distribution and mental well-being. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 17–29. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00006-0.

Otake, K., Shimai, S., & Tanaka-Matsumi, J. (2006). Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindness intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 361–375. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-3650-z.

Park, N., & Huebner, E. S. (2005). A cross-cultural study of the levels and correlates of life satisfaction among children and adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Research, 36, 444–456.

Partington, J., & Grant, C. (1984). Imaginary playmates and other useful fantasies. In P. Smith (Ed.), Play in animals and humans (pp. 217–240). New York: Basil Blackwell.

Pinquart, M., & Sörenson, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15, 187–224. doi:10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.187.

Prinstein, M. J., & Dodge, K. A. (2008). Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/.

Proctor, C., Linley, P.A., & Maltby, J. (2010). Very happy youths: benefits of very high life satisfaction among adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 98, 519–532. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9562-2.

Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 576–593. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00393.x.

Requena, F. (1995). Friendship and subjective well-being in Spain: A cross national comparison with the United States. Social Indicators Research, 35, 271–288. doi:10.1007/BF01079161.

Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R., Chen, X., Bowker, J., & McDonald, K. L. (2011). Peer relationships in childhood. In M. H. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (pp. 519–570). New York: Psychology.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2000). Friendships as a moderating factor in the pathway between early harsh home environment and later victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology, 36, 646–662. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.646.

Singer, J. L., & Singer, D. G. (1981). Television imagination and aggression: A study of preschoolers. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Singer, D., & Singer, J. L. (1990). The house of make-believe: Children’s play and developing imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Slee, P. T. (1993). Australian school children’ self appraisal of interpersonal relations. The bullying experience. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 23, 273–282. doi:10.1007/BF00707680.

Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., Danovsky, M., et al. (1997). The development and validation of the children’s hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22, 399–421. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399.

Stack, S., & Eshleman, J. R. (1998). Marital status and happiness: A 17-nation study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 527–536. doi:10.2307/353867.

Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138–161. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.138.

Strayer, J. (1980). A naturalistic study of empathic behaviors and their relations to affective states and perspective-taking skills in preschool children. Child Development, 51, 815–822. doi:10.2307/1129469.

Taylor, M. (1999). Imaginary companions and the children who create them. New York: Oxford University Press. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/.

Taylor, M., Cartwright, B. S., & Carlson, S. M. (1993). A developmental investigation of children's imaginary companions. Developmental Psychology, 29, 276–285. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.29.2.276.

Taylor, M., Carlson, S. M., Maring, B. L., Gerow, L., & Charley, C. (2004). The characteristics and correlates of high fantasy in school-aged children: Imaginary companions, impersonation and social understanding. Developmental Psychology, 40, 1173–1187. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1173.

Taylor, M., Shawber, A. B., & Mannering, A. M. (2009). Children’s imaginary companions: What is it like to have an invisible friend? In K. Markman, W. Klein, & J. Suhr (Eds.), The handbook of imagination and mental simulation (pp. 211–224). New York: Psychology.

Terry, T., & Huebner, E. S. (1995). The relationship between self-concept and life satisfaction in children. Social Indicators Research, 35, 39–52. doi:10.1007/BF01079237.

Thoilliez, B. (2011). How to grow up happy: An exploratory study on the meaning of happiness from children’s voices. Child Indicators Research, 4, 323–351.

Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L. (2012). Global and school-related happiness in Finnish children. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 601–619. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9282-6.

Vostrovsky, C. (1895). A study of imaginary companions. Education, 15, 393–398. http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.okanagan.bc.ca/ehost/.

Walker, S. S., & Schimmack, U. (2008). Validity of a happiness implicit association test as a measure of subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 490–497. doi:10.1037/t01069-000.

Wentzel, K., Barry, C., & Caldwell, K. (2004). Friendships in middle school: Influences on motivation and school adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 195–203. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195.

Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 395–412. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.3.395.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Holder, M., Coleman, B. (2015). Children’s Friendships and Positive Well-Being. In: Demir, M. (eds) Friendship and Happiness. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9603-3_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9603-3_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9602-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9603-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)