Abstract

We examine the origins of the disagreement of Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin regarding the significance and mechanism of sexual selection and relate this to differences in their views of human evolution, and of cognitive ability and esthetic sensibilities of various human and nonhuman populations. We trace subsequent versions of these differing views into the twentieth century, and the controversy between R.A. Fisher’s Darwinian “runaway” model of sexual selection by female choice (the “sexy son” model), and Wallacean models of sexual selection based on signs of greater fitness of males (the “healthy gene” hypothesis). Models derived from the latter, the “honest signal” and “handicap” models, are discussed, and we note that these different models, based on utility or beauty, are not necessarily mutually inconsistent.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Darwin

- Wallace and sexual selection

- Fisher’s runaway model of sexual selection

- “Good genes” versus “sexy son” models in sexual selection

- Female choice in sexual selection

- Darwin

- Wallace and the evolution of the human mind

1 Introduction

The ideas of Charles Darwin (1809–1882) on the evolution of secondary sexual characters, noted in The Origin of Species (1859) and developed in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871, 1874), spurred an important controversy which has remained an area of passionate contention to the present: What does “sexual selection” mean? How does it interact with natural selection? Does it apply to humans? Regarding the definition of sexual selection, Darwin suggested that males were struggling with each other for mates and that females were able to choose. But he provided no explanation for the reasons why females as a whole were generally “the choosing sex”, and for why a definite female would choose a definite male rather than any of his competitors: instead, he suggested that females were endowed with an “aesthetic sense”, a mysterious taste for beauty, which was governing their choices. This idea was largely criticized, first and foremost by Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), who doubted female animals might have the power to choose.

Wallace’s views can be viewed as a “utilitarian” approach that resolves sexual selection into natural selection: in this view, aesthetic traits are eventually always useful to their bearer, thus subject to being interpreted as advantageous to the general fitness of the individual. During the first half of the twentieth century, R.A. Fisher attempted to salvage Darwinian sexual selection with a run-away model: suggesting a mechanism for mere aesthetic preferences to develop traits, with no direct benefit. On the other hand, Wallacean utilitarian views have been considered the precursor to the good-gene model, for which wooing signals vigor. Later efforts to develop quantitative models of the early verbal suggestions have led to a controversy between the aesthetic and the utilitarian views.

Our paper is twofold. First we focus on the disagreement between Darwin and Wallace. We give an overview of its roots and its scale, showing how it involved not only sexual, but also aspects of natural selection, and we consider some differences in their understandings of how selection works. This analysis suggests that the classical theme of Wallace refusing “sexual selection” on grounds of his rejection of “female choice” is but a part of a larger picture. In particular we consider possible differences in their views on how the evolutionary principles apply to the human species. In the second part of this paper, we view Darwin and Wallace as rival scientists embodying two competing evolutionary principles, namely, Beauty and Utility, and how this has contributed to shaping the evolutionary debate of sexual selection throughout the Twentieth century and until today, as evidenced by several chapters of this book (see papers by Prum and Cézilly, this volume).

2 Darwin and Wallace: a Range of Disagreements

Sexual selection is Darwin’s second important concept. In 1871 (t. I, p. 256), he defined it in a rather general fashion, as “the advantage which certain individuals have over other individuals of the same sex and species, in exclusive relation to reproduction”. Darwin decomposed sexual selection in two classes of phenomena: in some species, male competition for females is evident while, in others, female choice of males is clearly shown (Darwin 1859, pp. 87–90). Males, particularly in polygynous species, might fight over females, leading to selection for physical size and weaponry, as in the case of the male elk’s antlers. Females, on the other hand, would choose among males, but on what basis? How does it help the peahen’s posterity to choose a peacock with a splendid tail, for example? Darwinian female choice focuses on beauty for beauty’s sake and does not emphasize the utility of exaggerated features, like ornaments. In contrast to this view, Wallace noted that Darwin attributed colors or courtship displays in birds and insects to sexual selection, but he thought that the ‘greater vigor’ and ‘higher vitality’ of males might somehow be associated with, or perhaps lead to their greater coloration or activity. He also attributed a role to the protective value of drab colors for females. Besides, he emphasized how elaborate male crests and erectile feathers might function as species recognition signals, or as a means to frighten away predators, not to attract females.

It can be said that Wallace emphasized both the protective and the signaling value of color while Darwin stressed its aesthetic value. But beyond the specific issue of sexual selection, Darwin and Wallace entertained different views on several issues, and not only on the mechanisms that account for sexual dimorphism.

2.1 Darwin and Wallace as Codiscoverers

When Darwin received Wallace’s Ternate manuscript called “On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection” on 18 June 1858, he immediately wrote to his friend and mentor, the geologist Charles Lyell: “Your words have come true with a vengeance that I should be forestalled. You said this when I explained to you here very briefly my views of “Natural Selection” depending on the Struggle for existence. I never saw a more striking coincidence. If Wallace had my M.S. sketch written out in 1842 he could not have made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as heads of my chapters”. And, facing the future publication of Wallace’s manuscript, Darwin concluded: “all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed” (Darwin to Lyell, 18 June 1858, in Darwin 1991, p. 107).

In fact, Wallace’s letter was not the first, but the third that the self-educated collector had sent to the famous author of the Voyage of the Beagle: the two men were in touch since 10 October 1856, and Wallace knew that Darwin was preparing a big book “on species and varieties, for which he ha[d] been collecting information for 20 years”. The young naturalist (he was only 35 at the time) thought that Darwin’s work might save him the trouble of “proving that there is no difference in nature between the origin of species and varieties”, as he wrote to his friend the entomologist Henry Walter Bates (Wallace to Bates, 4 Jan. 1858, in Marchant 1916, t. I, p. 67).

The convergences in the ideas of these two men were indeed remarkable. Especially both referred to a form of “struggle for existence” (Wallace 1858, p. 54). Nevertheless, as there were a number of points of differences between them, Darwin and Wallace have also been cast as rivals and competitors by others: some claim that Wallace was the true discoverer of the mechanism of evolution and that Darwin usurped the credit; others that Darwin was the true discoverer and Wallace’s initial essay was not an adequate statement of the mechanism of evolution. Such claims no doubt generate a certain notice, but they are not well supported by the comments and attitudes of the two men themselves, each of whom referred to the other as co-discoverer on many occasions, both privately and publicly. The two principals were friends and admired each other; and indeed there was much to admire: in addition to their writings on evolution, both made other, substantial contributions to science, and both would be remembered today, had they never written about evolution.

What were the main differences? First and foremost, Darwin viewed the modification of physical and behavioral traits in domestic animals and plants by selective breeding as a kind of metaphor, an indication of what selection by natural forces might be able to accomplish. Wallace, on the other hand, viewed domestic species as essentially abnormal, and considered that they would rapidly return to the ancestral type if released to the wild. In his initial essay of 1858 he sought to refute

the assumption that varieties occurring in a state of nature are in all respects analogous to or even identical with those of domestic animals, and are governed by the same laws as regards their permanence or further variation”. In contrast, Wallace thought that “there is a general principle in nature which will cause many varieties to survive the parent species, and to give rise to successive variations departing further and further from the original type, and which also produces in domesticated animals, the tendency of varieties to return to the parent form. (Wallace 1858, p. 54)

Thus, Wallace never agreed with Darwin’s frequent and prominent use of human artificial selection of domestic varieties as an argument supporting the possibility of nature selecting new varieties. He disputed the usefulness of domestication as a sound analogy for understanding the modification of species in the wild: the possibility that domestic breeds would revert to an original “type” when becoming feral was a stumbling block to Wallace (Gayon 1998; Beddall 1968). Consistently with this critique of Darwin’s foundational analogy with the world of breeding, Wallace never fully accepted the phrase “natural selection”, as it was based on and encapsulated the analogy between Nature and the breeders’ “selecting” actively albeit unconsciously some traits over others. Wallace did not like the term at first, and examination of his copy of the Origin shows that he cautiously crossed the word (Beddall 1988). In several letters to Darwin, Wallace repeatedly denounced the “agentive” connotations of the word “selection” and he was constantly urging Darwin to state that nature is not a breeder capable of conscious choice (Gayon 1998; Hoquet 2011). Wallace was so concerned with a possible personification of “selection”, that he was even responsible for Darwin’s introducing Herbert Spencer’s phrase “survival of the fittest” in the fifth edition of the Origin (1869). It’s ironic that, in spite of his early reluctance to accept the term selection, Wallace later became a strong and convinced selectionist. His Darwinism (1889) reshaped Darwin’s theory as a pan-utilitarianism, promoting an interpretation of Darwin that was so radical that George Romanes, another disciple of Darwin, accused Wallace of being “ultra-Darwinian” (see below sect. 2.1).

A third difference bears on what is now called “the levels of selection”. Both Darwin and Wallace strongly believed in the causal power of natural selection, but they disagreed on the level at which competition occurs: Darwin referred to competition between individuals, while Wallace, though his initial statement referred to competition among individuals, tended to focus on competition between populations. This difference has been often noted, at least since the work of paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn (1894) (for instance by Bowler 1976; Gayon 2009a; Bock 2009, Ruse, this volume). H.F. Osborn called the Darwin-Wallace moment “one of the most striking of all the many coincidences and independent discoveries in the history of the Evolution idea” (1894, p. 243). However, when Osborn compared Darwin and Wallace’s contributions to the 1st July 1858 meeting of the Linnaean Society, he concluded: “remarkable as this parallelism is, it is not complete. The line of argument is the same, but the point d’appui is different. Darwin dwells upon variations in single characters, as taken hold of by Selection; Wallace mentions variations, but dwells upon full-formed varieties, as favorably or unfavorably adapted” (1894, p. 245; emphasized by Osborn). The struggle is much more intense in the Darwinian world, so that the slightest difference in organization or instinct can have the most dramatic effect on individual survival; on the other hand, in the Wallacean world, environmental change occurs, and some varieties happen to be adapted to it. In contrast with Darwin’s focus on individual variation, Wallace’s 1858 paper focuses on varieties: “the very clear recognition of the importance of individual differences” came only later in his writings and “marked a significant development in his thought” (Bowler 1976, p. 17). Such difference in emphasis is somewhat reminiscent of a dispute that arose in the twentieth century among the 3 founders of the Modern Synthesis. R. A. Fisher and J. B S. Haldane viewed evolution as proceeding through single gene selection, whereas Sewall Wright emphasized gene interaction and saw collections of genes as the unit of selection, giving rise to Haldane’s famous paper “A defence of beanbag genetics” (Haldane 1964).

So we have listed three disagreements of varying importance between Darwin and Wallace: on the value of the analogy with domestic breeds; on the appropriateness of the term “natural selection”; and perhaps on the levels of selection and the difference between variations and varieties. We come now to a major difference that forms the theme of this paper.

2.2 Disagreement on Sexual Selection

It should be added that, from the very outset, Darwin and Wallace disagreed about sexual selection, its importance in the development of secondary sexual characteristics, and its role in human evolution. The theme of sexual selection is treated in a short section in the chap. 4 of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859, pp. 87–90), and is also briefly mentioned in an earlier essay published jointly with Wallace’s paper in 1858 (see below). Darwin later wrote an entire two-volume book on the subject (1871), revealing the importance he ascribed to this process. Between the publication of his two major works, and especially around 1867–1869, Wallace and Darwin were both working on the issue of sexual characters and had an extensive correspondence on the subject, trying to resolve their differences (collected and analyzed by Kottler 1980, 1985). It seems that once again, Wallace “still anticipated ideas in the most embarrassing manner” (Irvine 1955, p. 184) and Darwin was obviously annoyed by this new coincidence. He wrote to Wallace, 29 April 1867: “It is curious, how we hit on the same ideas” (Marchant 1916, t. I, p. 184). But 2 days later, on May 1st, Wallace replied to Darwin:

I had thought of a short paper on The Connection between the colors of female birds and their mode of nidification—but had rather leave it for you to treat as part of the really great subject of sexual selection —which combined with protective resemblances and differences will I think when thoroughly worked out explain the whole coloring of the animal kingdom. (1st May 1867, http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-5522)

As this last quote shows, Wallace constantly showed unabashed deference to Darwin and sent him all his notes on the topic. But beyond his submission to Darwin’s priority, there were strong disagreements between the two men—and Darwin was trying his best to bridge the gap between them and have them come to an agreement. On 23 September 1868, Darwin restated the problem of their divergence between protection and sexual selection: “We differ, I think, chiefly from fixing our minds perhaps too closely on different points, on which we agree” (Marchant 1916, t. I, p. 225). Darwin tried to bring by all possible means closer agreement between him and Wallace. However, eventually, it turns out that Wallace did not think sexual selection was a significant evolutionary factor although he seemed, at times, to waver somewhat.

An early discussion of sexual selection appears in the portion of Darwin’s 1844 essay that was read to the Linnaean Society in July 1858, along with Wallace’s paper “On the Tendency of Varieties to depart indefinitely from the Original Type.” Darwin wrote:

Besides this natural means of selection, by which those individuals are preserved, whether in their egg, or larval, or mature state, which are best adapted to the place they fill in nature, there is a second agency at work in most unisexual animals, tending to produce the same effect, namely, the struggle of the males for the females. These struggles are generally decided by the law of battle, but in the case of birds, apparently, by the charms of their song, by their beauty or their power of courtship, as in the dancing rock-thrush of Guiana. The most vigorous and healthy males, implying perfect adaptation, must generally gain the victory in their contests. This kind of selection,however, is less rigorous than the other; it does not require the death of the less successful, but gives to them fewer descendants. The struggle falls, moreover, at a time of year when food is generally abundant, and perhaps the effect chiefly produced would be the modification of the secondary sexual characters, which are not related to the power of obtaining food, or to defense from enemies, but to fighting with or rivaling other males. (Darwin 1858, p. 50)

In this passage, as later in the Origin, sexual selection appears to be an umbrella term for two different kinds of phenomena: male-male rivalry leading to armaments; female preferences leading to ornaments. The first of these mechanisms, rivalry among males, was generally undisputed. Wallace accepted it (1905, t. II, pp. 17–18) and he considered “a very general fact that the males fight together for the possession of the females. This leads … to the stronger or better-armed males becoming the parents of the next generation … From this very general phenomenon there necessarily results a form of natural selection, which increases the vigor and fighting power of the male animal” (1889, p. 282). Vigor was a rationale for including male-male competition as part of natural selection.

What was really at stake was the idea that female animals have the capacity to choose their mates. Darwin had strongly supported the possibility of female aesthetic choice. In the Origin, he wrote: “if man can in a short time give elegant carriage and beauty to his bantams, according to his standard of beauty, I can see no good reason to doubt that female birds, by selecting, during thousands of generations, the most melodious or beautiful males, according to their standard of beauty, might produce a marked effect” (1859, p. 89). For Darwin then, it was not unreasonable to invoke a rudimentary aesthetic sense on the part of the peahen as a factor in the selection of the peacock’s tail. Note that he invokes here the model of artificial selection by humans—a model that Wallace presumably would have rejected.

Wallace did not reject female choice in general, but he thought that female preferences targeted male vigor, not beauty. Accordingly, he endorsed two main objections that had been raised against females’ taste for the beautiful:

a/Female choice, if it seeks for sheer beauty (unrelated to the signaling of any quality), undermines the power of natural selection, as this mechanism is only concerned with benefits. Especially, female preferences for this or that trait would have no evolutionary foundation.

b/Assuming a sense of beauty in lower animals raises the broader question of animal faculties. As Gayon (2009b) puts it, female choice amounts to claiming “that many animals, from fishes to primates, have perceptive, emotional and cognitive abilities that make them able to discriminate and choose their sexual partners. This claim raised no more or less than the problem of the gradual evolution of the mind”.

Accordingly, Wallace thought that sexual selection (sensu female choice) was an unnecessary hypothesis (Gayon 2009b). Wallace could not accept the notion of peahens with an aesthetic sense and was seeking for usefulness of traits.

These points are now well-established in the literature (Cronin 1991; Milam 2010). But other elements should also be brought to the fore. First, as noted earlier, Wallace’s environmentalist conception of natural selection (Nicholson 1960) should be differentiated from Darwin’s own understanding of natural selection as “a competitive process within the species, which can change the species even under unchanged conditions” (Gayon 2009b). This may ultimately impact on their contrasted views on sexual selection: Wallace’s reluctance to accept sexual selection is linked to the fact that sexual selection is “a purely competitive process among the members of one sex within the species”; while, for Darwin, sexual selection “was based exclusively upon differential reproductive success among individuals of one sex” and “did not rely upon an adaptive advantage” (Gayon 2009b). For Wallace, sexual selection “was outside Darwinism”, while for Darwin, sexual selection, “because of its primarily competitive and individualistic nature, revealed something important about how selection in general works in nature” (Gayon 2009b).

Darwin’s sexual selection aims at explaining certain largely male traits: weapons and beauty, or sex differences “in structure, colour, or ornament”, as Darwin himself puts it. Darwin focuses, among other traits, on exuberant coloration in males. Wallace has a different take on this question. He is interested in the relatively plain or drab coloration of the females compared to the males in many bird species; he thinks it is the result of natural selection, to protect them from predation as they nested, while the males in those cases are less subjected to such selection. The focus on coloring shows the paramount importance of protection. Two positions are open: one (Darwin’s) claim that colouration results from female preference for beautiful feathers in males; the other (Wallace’s) stresses the protective value of coloration in females. Darwin himself was oscillating (Darwin to Wallace 16 September 1868):

You will be pleased to hear that I am undergoing severe distress about the protection & sexual selection: this morning I oscillated with joy towards you: this evening I have swung back to old position, out of which I fear I shall never get. (Marchant 1916, t. I, p. 222–223)

Wallace took great pride in having shown the usefulness of phenomena which were previously regarded as non-adaptive. He was an extreme utilitarian and, as a result, a pan-selectionist. Wallace argued we should look at nature assuming that each feature we see is useful:

… other slight differences which to us are absolutely immaterial and unrecognizable, may be of the highest significance to these humble creatures, and be quite sufficient to require some adjustments of size, form, or color, which natural selection will bring about. (1889, p. 148)

Wallace also rephrased Darwin’s “great general principle” as: “all the fixed characters of organic beings have been developed under the action of the law of utility”, entailing for instance that “so remarkable and conspicuous a character as color, which so often constitutes the most obvious distinction of species from species or group from group, must […] in most cases have some relation to the wellbeing of its possessors.” (1889, p. 187–188).

Another important issue between Darwin and Wallace is sex-linked inheritance. On that matter, it should be noted that the first words of the section on sexual selection in the Origin provides us with an important key to understand Darwin’s mechanism: peculiarities appear “in one sex and become hereditarily attached to that sex” (1859, p. 87). Darwin called Wallace’s attention on their diverging views on inheritance in his letter dated 5 May 1867 (Marchant 1916, I, p. 185). As Kottler put it (1980, p. 204): “At the heart of their disagreement was a basic difference of opinion about the laws of inheritance.” At the climax of the controversy (23 September 1868) Darwin wrote to Wallace: “I think we start with different fundamental notions on inheritance.” Wallace believed that, as a rule, variations as they first appeared, were inherited equally by both sexes, and that, afterwards, natural selection had to convert equal inheritance into sex-limited inheritance. Whenever one sex is endangered more than the other (for instance by conspicuous coloration), natural selection would convert the equal inheritance of the variations sexually selected, into sex-limited inheritance, so that the sex in greater danger loses conspicuous coloration. Following his belief in the generality of equal inheritance, Wallace attributed the drab coloration of the less conspicuous sex to natural selection for the sake of concealment of the individuals in greater danger. On the other hand, Darwin was in favor of sex-limited inheritance of traits: in his view, female animals never had to “lose” bright coloration or to be modified for protection—as they never acquired gaudy feathers.

We now understand that it is a misconception to regard Wallace as opposed entirely to sexual selection. Besides, while Wallace thought that sexually dimorphic traits were initially the same in both sexes and natural selection had to make the sex in greater danger less conspicuous, Darwin claimed that sexually selected traits are only present in one sex, and natural selection has to keep the sex in greater danger less conspicuous (Kottler 1980). Such disagreement reflects the fact that the actual (Mendelian) laws of genetics were of course unknown to both of them.

2.3 The Riddle of Human Evolution

The question of sexual selection was also closely linked to the question of human evolution. First, sexual selection was deeply tied with anthropomorphic views. The flavor of Wallace’s thinking on the topic can be seen in a well-known passage from his book Darwinism:

It will be seen, that female birds have unaccountable likes and dislikes in the matter of their partners, just as we have ourselves, and this may afford us an illustration. A young man, when courting, brushes or curls his hair, and has his moustache, beard or whiskers in perfect order and no doubt his sweetheart admires them; but this does not prove that she marries him on account of these ornaments, still less that hair, beard, whiskers and moustache were developed by the continued preferences of the female sex. So, a girl likes to see her lover well and fashionably dressed, and he always dresses as well as he can when he visits her; but we cannot conclude from this that the whole series of male costumes, from the brilliantly coloured, puffed, and slashed doublet and hose of the Elizabethan period, through the gorgeous coats, long waistcoats, and pigtails of the early Georgian era, down to the funereal dress-suit of the present day, are the direct result of female preference. In like manner, female birds may be charmed or excited by the fine display of plumage by the males; but there is no proof whatever that slight differences in that display have any effect in determining their choice of a partner. (1889, pp. 286–287)

But beyond these considerations, the genesis of Darwin’s concept of sexual selection is, on a deeper level, intimately tied to the puzzle of human races. As Desmond and Moore have shown (2009, p. 282), Darwin’s earlier notice of sexual selection was found in a manuscript note on Knox’ Races of man. Darwin wrote to Wallace (March 1867): “…my sole reason for taking it up [i.e. the subject of man] is that I am pretty well convinced that sexual selection has played an important part in the formation of races, and sexual selection has always been a subject which has interested me much.” (Marchant 1916, t. I, p. 182). And again, on 29 April 1867: “in my Essay upon Man I intend to discuss the whole subject of sexual selection, explaining as I believe it does much with respect to man.” (t. I, p. 183).

Darwin and Wallace disagreed on the importance of sexual selection in the evolution of secondary sexual characteristics, and also on the question of human evolution.

Darwin sought naturalistic explanations for phenomena, including behavioral phenomena, and considered human capacities such as cognition, emotions, aesthetic feelings to be traits that had evolved, and thus could also exist in other species. He wrote a book about the expression of emotions in animals (1872). While there is still debate on the question of animal cognition, it is fair to say that modern neurology and studies of animal behavior have largely vindicated Darwin’s basic viewpoint (e.g., Griffin 2001).

Wallace had a rather Cartesian view of human mental abilities. He believed that some perhaps mystical principle was involved in the generation of the human mind and its consciousness. As a result, the intelligent design movement has apparently adopted Wallace in recent years, claiming that his version of evolution anticipated their claims (Flannery 2008, 2011).

Darwin’s view: A Gradation of Mental Powers

It is particularly interesting that Darwin published his major discussion of sexual selection in the same book as his treatment of human evolution, which was also not treated extensively in the Origin. This juxtaposition may relate to a deeper division between him and Wallace, involving their views on human evolution, as well as their views on sexual selection by female choice: the two differences may in fact have been related.

Why should these two great intellects be likely to differ on the subject of human evolution, and also on the possibility of sexual selection by female choice? There is a strong temptation here to indulge in what is sometimes termed whig history—the application of contemporary norms to past historical events or figures. Both Darwin and Wallace were of course Victorians, with constant immersion in the racial, ethnic and gender biases of the period. However, let us note at the outset that Wallace was, among other things, a strong feminist, and it is thus difficult to see his opinion as simply the result of male bias. Similarly, Darwin was an abolitionist and a strong opponent of slavery, and indeed it has been argued that this was a major factor in his development of the theory of evolution by natural selection (Desmond and Moore 2009), so it becomes difficult to ascribe his views on human evolution to racism.

We will argue here that their disagreements about sexual selection as well as about human evolution probably did not arise primarily from Victorian biases, but rather had roots in fundamentally different conceptions about the evolutionary relations of humans to other species, and that this difference in turn reflected, at least in part, differences in their experiences as naturalists.

To understand this difference we need to consider the backgrounds of both men. A major difference in the personal backgrounds of Darwin and Wallace was their experience of non-European peoples and cultures. Darwin had traveled, of course, circumnavigating the globe for 5 years in the Beagle, with extensive inland excursions in South America and elsewhere, but he was usually either in the company of fellow Englishmen or in any case supported, protected and cushioned, directly or indirectly, by the great authority of the British Navy. According to all accounts, he was a very tolerant person, not given to aggression or autocratic assertion, and a Whig politically, strongly opposed to slavery. Nevertheless he was also a product of mid-Victorian British culture, with a strong belief in progress and little in-depth personal knowledge of non-European cultures (see Browne 1995, especially chap. 10, pp. 234–253; Desmond and Moore 2009). His expressed surprise when encountering the natives of Tierra del Fuego serves to illustrate this and makes a sharp contrast with the “domesticated” figure of the 3 natives transported back to South America on the Beagle:

The Fuegians rank among the lowest barbarians; but I was continually struck with surprise how closely the three natives on board H.M.S. Beagle, who had lived some years in England, and could talk a little English, resembled us in disposition and in most of our mental faculties. (Darwin 1871, t. I, p. 34)

Much of his other information regarding other “savage” peoples came from anecdotal accounts by a variety of travelers. Continuing the quotation above, he states

If no organic being excepting man had possessed any mental power, or if his powers had been of a wholly different nature from those of the lower animals, then we should never have been able to convince ourselves that our high faculties had been gradually developed. But it can be clearly shown that there is no fundamental difference of this kind. … there is a much wider interval in mental power between one of the lowest fishes … and one of the higher apes, than between an ape and man. (Darwin 1871, t. I, pp. 34–35)

On the other hand,

Nor is the difference slight in … intellect, between a savage who does not use any abstract terms, and a Newton or Shakespeare. Differences of this kind between the highest men of the highest races and the lowest savages are connected by the finest gradations. … there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties. (Darwin 1871, t. I, p. 35)

Darwin strongly believed in the unity of the human family, but (it is like the other face of the same coin), as a result, he tended to view, possibly unconsciously, other populations as “uncivilised” (for instance, 1859, p. 38, 140). His belief in progress entailed gradual improvement by stages, entailing that the native Fuegians represented earlier evolutionary stages, less advanced than Europeans. However, he would clearly have disagreed with the theory of retrogression or degradation, espoused by, among others, the Archbishop of Dublin Richard Whately (1855), or George Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll (1869). According to the theory of degradation, the ‘savage races’ of mankind presented a degradation from a previously more advanced civilized state, and Darwin clearly refuted these theories in his Descent (Darwin 1871, t. I, p. 181; see also Gillespie 1977).

In any case, Darwin clearly thought of the human species as being derived evolutionarily from earlier primates, and from these and many other passages, it’s clear he saw no unbreachable barrier separating humans from other animal species, and believed there had been a succession of evolutionary stages from earlier primates to humans, with no impermeable boundary. He thus had no difficulty with the idea that the rudimentary beginnings of human intellectual, moral and esthetic sensibilities could be found in lower animals, an attitude evident in the very title of another of his books, On the Expression of the Emotions in Animals and Man (1872). And he also noted the profound unity of all human beings, in sharing the same basic emotions (see Radick 2010).

A rather direct indication of the link between his views on human evolution and his adoption of sexual selection by female choice is found in an addition to chap. 8 in the second edition of The Descent of Man. Where the first edition read:

No doubt this implies powers of discrimination and taste on the part of the female which will at first appear extremely improbable; but I hope hereafter to shew that this is not the case. (1871, t. I, p. 259)

The second edition reads:

No doubt this implies powers of discrimination and taste on the part of the female which will at first appear extremely improbable; but by the facts to be adduced hereafter, I hope to be able to show that the females actually have these powers. When, however, it is said that the lower animals have a sense of beauty, it must not be supposed that such sense is comparable with that of a cultivated man, with his multiform and complex associated ideas. A more just comparison would be between the taste for the beautiful in animals, and that in the lowest savages, who admire and deck themselves with any brilliant, glittering, or curious object. (1874, p. 211)

As noted by others (Prum 2012), Darwin was quite serious in ascribing an aesthetic sense to other species. The difference in mentality, emotions and sensibility between humans and other creatures was one of degree, and not fundamental: these qualities were also evolving.

Wallace’s View: Beyond the Scope of Natural Selection

Wallace presents a contrast. Having spent many years largely on his own, first in South America and then in Southeast Asia, in intimate contact with native populations, he could appreciate from personal experience the competence and intelligence of the peoples he encountered, and was convinced that the mentality and reasoning power of ‘savages’ was quite comparable to that of ‘civilized’ Europeans. Thus he had a unitary view of the various kinds of humanity, as a single species, with great variety, but all at the same intellectual level. Like Darwin, he was a mid-Victorian, but his personal history was different, and he was also perhaps more of a maverick than Darwin, far more active politically, espousing a variety of political and social causes.

Reviewing Darwin’s The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, he wrote that the “vast amount of the superiority of man to his nearest primate relatives is what is so difficult to account for” (Wallace 1871, p. 183). Darwin, as we have seen, did not share this view and considered that the differences between other animals and humans, though indeed large, were essentially of degree rather than fundamental.

Further, Wallace continues, “It must be admitted that there are many difficulties in the detailed application of [Darwin’s] views, and it seems probable that these can only be overcome by giving more weight to those unknown laws whose existence he admits but to which he assigns an altogether subordinate part in determining the development of organic form” (Wallace 1871). These “unknown laws” were mentioned by Darwin in the Origin: the laws of growth, development, inheritance, correlation, the “direct action of the environment,” and the laws of habit and instinct—many of these have become major areas of twentieth and twenty first century biological research but were largely unexplored in Darwin’s day. Wallace tended to view some of these as evidences of a controlling Mind or Supreme Intelligence, and his involvement in spiritualism and related subjects in his later years no doubt reflects this view (Slotten 2004).

In a joint review of the tenth edition of Charles Lyell’s Principle of geology (1867) and of the sixth edition of his Elements of geology (1865), Wallace developed the following argument: the brain of the “lowest savages” (Wallace thinks of the Australians or the Andaman islanders) and, probably, those of “the pre-historic races,” was an organ barely “inferior in size and complexity to that of the highest types (such as the average European)”; in other terms, two or three thousand years would be sufficient for them to acquire, by a “process of gradual development”, the average results of humans of higher civilizations. In contrast to that, the mental requirements of these lowest savages, “are very little above those of many animals”: “the higher moral faculties and those of pure intellect and refined emotion are useless to them, are rarely if ever manifested, and have no relation to their wants, desires, or well-being” (Wallace 1869, p. 91–392). Hence the following paradox: “How, then, was an organ developed so far beyond the needs of its possessor? Natural selection could only have endowed the savage with a brain a little superior to that of an ape, whereas he actually possesses one but very little inferior to that of the average members of our learned societies.”

In his copy of this text, Darwin wrote in the margin a vehement “No”, triple scored and showered with exclamation points (Irvine 1955, p. 187).

A curious and perhaps ironic end-note on Wallace and sexual selection may also be mentioned. He did, in fact, allow for the possibility of sexual selection by female choice in one species, namely in humans. Though he rejected Darwin’s speculation that hairlessness and skin color in humans were products of sexual selection, he nevertheless invoked a kind of sexual selection by female choice in another area. He thought violent tendencies in humans would gradually diminish and intelligence increase, as women chose mates and had children preferentially with gentler, more intelligent males (Wallace 1913). He obviously followed the logic of sexual selection by female choice, but was not willing to grant it status as an evolutionary force, except in the (for him, exceptional) case of humans. Darwin, the mid-Victorian, tended somewhat to pessimism, while the younger Wallace, like many Europeans of the Edwardian era, was in some ways an optimist, believing in incremental progress in human society. Wallace died in 1913, too soon to witness the events that began a year later in Sarajevo.

In summary, Darwin’s and Wallace’s views diverged on two accounts: one related to the mental abilities of animals, one related to the mental capacities of so-called “uncivilized men”. On the first point, Darwin thought it was not unreasonable to invoke a rudimentary aesthetic sense on the part of the peahen as a factor in the selection of the peacock’s tail, whereas Wallace could not accept the notion of peahens with an aesthetic sense. On the second point, while both men recognized the unity of the human family, Darwin was struck by the lowness of non-European civilizations, to the point that he estimated that the distance between human and animal brains was not so large; while Wallace emphasized the gap between humans and non-human animals and stressed the seeming impotence of natural selection when it came to explaining human higher mental faculties. Darwin had a continuous view of mental powers, from non-human animals to humans; while Wallace, having a sense of a strong discontinuity between humans and non-humans, thought it was a sufficient argument to repel the role of natural selection and call for other (supernatural) agencies.

Darwin saw humans as simply part of an evolutionary continuum, their mental, aesthetic and emotional qualities as differing in degree, but not fundamentally from those of other animals. In contrast, Wallace viewed humans as a special case. In particular, he considered that human mentality, cognition, aesthetic senses, and spirituality could not be a product of natural selection, and it was difficult for him to accept the idea of an aesthetic sensibility in non-human animals. He was not religious in the conventional sense of organized religion, but he viewed humans as more than simply products of natural selection, and this is no doubt connected to his life-long interest in spiritualism and the occult. Eventually, in a review of E.B. Poulton’s Colours of Animals, Wallace stated (1890, p. 291): “This most interesting question … in all probability, will not be finally settled by the present generation of naturalists.”

3 Shaping the Darwin/Wallace Debate: What the Positions of Darwin and Wallace Imply.

Now that we have analyzed the complexity of the debate between Darwin and Wallace, we will approach the historical steps towards the rephrasing of their divergence in terms of Utility vs Beauty.

3.1 Sexual Selection During the “Eclipse of Darwinism”

The historian Peter J. Bowler and others have noted that, for a period of several decades before and to some extent after 1900, Darwin’s version of evolution by natural selection was out of favor with many biologists, who supported other types of evolutionary theory: Lamarckism, theistic evolution, mutationism, orthogenesis (Bowler 1983, 1988). While Darwin’s sexual selection is often considered merely an expression of Victorian prejudice, Bowler claims that, “during the eclipse of Darwinism, sexual selection was even less popular among biologists than natural selection was” (Bowler 1984, p. 314). In other terms, in spite of its familiar ring for a Victorian reader, Darwin’s concept elicited more criticisms than positive responses. And indeed, although it didn’t evoke the great eruption of criticism that greeted the appearance of the Origin, Darwin’s theory of sexual selection did attract criticism and satire, as in the lampoon by Richard Grant White, The Fall of Man, or the Loves of Gorillas (1871), in which gorillas exercise sexual selection by mating with a variety of other species. Such ridicule of sexual selection in the lay press may have served sometimes as proxy for opposition to Darwin’s other mechanism, natural selection, and to evolutionary thought in general.

With regard to animal coloration, Darwin’s aesthetic hypothesis was viewed as emphasizing love and beauty, whereas Wallace’s adaptationist standpoint emphasized vigor and safety (mimicry, protection). Ironically, enemies of Darwin’s natural selection were quite at ease with the idea of sexual selection as it seemed to resurrect a metaphysical (and non utilitarian) kind of beauty. For instance, the Duke of Argyll’s Reign of Law (1867) discussed coloration in hummingbirds: he asked why a topaz crest should be selected in preference to a sapphire one. Focusing solely on utility, Darwin’s natural selection seemed to be missing the point that is central to Argyll’s conception of nature: beauty for its own sake. But sexual selection appeared to restore beauty to nature. It should be noted that early reactions to Darwin’s model of sexual selection, including that by Wallace, considered it as separate from, or even contradicting natural selection.

While some recent readers have suggested that Darwin integrated beauty into nature (e.g. Cronin 1991), many of his contemporaries thought the tie between beauty and divine creation was impossible to sever: as soon as Darwin acknowledged the existence of beauty, he had reintroduced a teleological feature in nature. The reluctance of many biologists (including Wallace) to follow Darwin in this model starts with what was considered the special status of beauty. It was necessary to decide whether Darwin’s incorporation of an aesthetic quality such as beauty among animals, was consistent with a naturalistic framework.

The rephrasing of the Darwin-Wallace debate in terms of Beauty vs Utility owes a lot to the biologist George J. Romanes (1848–1894), who was described by the Times as “the biological investigator upon whom, in England, the mantle of Mr. Darwin has most conspicuously descended” (quoted by Thiselton-Dyer 1888). Romanes was fighting with Wallace over Darwin’s legacy. He depicted Wallace as a supporter of a pan-utilitarian stance. For instance, Romanes attributed to Wallace the thought that “natural selection has been the sole means of modification …Thus the principle of Utility must necessarily be of universal application” (1892, t. II, p. 6). Romanes referred to “two great classes of facts in organic nature: namely, those of Adaptation and those of Beauty. Darwin’s theory of descent explains the former by his doctrine of natural selection, and the latter by his theory of sexual selection” (Romanes 1892). Apparently, Romanes committed to both Darwinian mechanisms, but by phrasing the problem this way, with a clear divide between Utility and Beauty, he, willingly or not, confirmed the idea that natural and sexual selection were two rather separate mechanisms, having little to do with each other.

In fact, while Darwin saw at first no contradiction between natural and sexual selection, he saw clearly that sexual selection could lead to the evolution of non-adaptive traits. As a result, his followers asked whether sexual selection challenged what Darwin had called the “paramount power of natural selection” (Darwin 1859, p. 84). In 1877 Eduard von Hartmann claimed that Darwin weakened his case for natural selection by trying to take beauty (and not merely utility) into account (Hartmann 1877; Hoquet 2009).

While Darwin and Wallace debated on the sex-limited character of variation, their followers put forward the topic of the “greater eagerness” of males. Both Darwin and Wallace, but maybe Wallace even more than Darwin, had stressed the idea of the “greater vigor” of males. In 1883, Harvard and Johns Hopkins biologist William Keith Brooks suggested that a more fundamental explanation was required in order to explain why males have stronger passions (Brooks 1883). If it is a general rule that males are more modified than females, then biology needs a theory of heredity that accounts for this fact.

Brooks disagreed with Wallace’s hypothesis that females were drab in order to be less visible to predators: he noted that in species where both males and females brood, a colour dimorphism subsists. He supported Darwin’s hypothesis that “the excessive exposure of the male to the action of selection, natural and sexual” is the cause of his being modified. Male characters being useful, they have been positively selected for; while there was no such pressure for the evolution of corresponding female traits. “No one can doubt the truth of this statement, but it does not go to the root of the matter. The question is not how peculiarities useful to the male alone have been restricted to that sex, but why the female has not acquired another set of characteristics to fit her for her peculiar needs” (Brooks 1883). Brooks explicitly put forward the problem of sex-limited inheritance. The “provisional hypothesis of pangenesis”, described in Darwin’s book Variation under domestication (1868) was never introduced to later editions of the Origin of Species; but it played an important role in W.K. Brooks’ understanding of his ideas on sexual selection. Brooks suggested that transmission of gemmules by the mother was more rare than transmission by the father, explaining why males vary more than females.

A different approach to the question of sexual dimorphism was taken by Patrick Geddes and Arthur J. Thomson (1889). For them, “no special theory of heredity is required,—the males transmit the majority of variations, because they have most to transmit”. Darwin and Wallace’s theory are considered symmetrical: sexual selection is, with Darwin, acknowledged as a minor accelerant, natural selection is, with Wallace, understood as a retarding “brake” on the differentiation of sexual characters, but for these authors, the key to sexual dimorphism is to be found in a constitutional or organismal origin, which they term “the katabolic or anabolic diathesis which preponderates in males and females respectively” (Geddes and Thomson 1889). (It should be noted that these various speculations occurred before the the actual laws of Mendelian heredity were rediscovered).

We see how, with Brooks and Geddes & Thomson, the debate on sexual selection has moved away from the topic of female choice to encompass the question of male vigour and male variability (allegedly superior to that of females).

In a 1903 book dedicated to W.K. Brooks, Thomas Hunt Morgan argued vigorously against sexual selection theory. He gave a comprehensive list of objections, bearing both on natural and sexual selection, mixing cartoonesque and biological remarks. Morgan coarsely caricatured sexual selection in anthropomorphic terms: “It sounds a little strange to suppose that women have caused the beard of man to develop by selecting the best-bearded individuals, and the compliment has been returned by the males selecting the females that have the least amount of beard” (Morgan 1903). His objections also included observations bearing on the laws of sex-limited inheritance: “It is also assumed that the results of the selection are transmitted to one sex only. Unless, in fact, the character in question were from the beginning peculiar to only one sex as to its inheritance, the two sexes might go on forever selecting at cross-purposes, and the result would be nothing”(Morgan 1903).

Thus, Morgan rejected both Darwin and Wallace: the numerous difficulties that the theory of sexual selection had met led to rejecting it as an explanation of the secondary sexual differences amongst animals; but Wallace’s explanation of the sex differences as due to the excessive vigour of the male, was equally unsuccessful. In the end, Darwin's theory was only useful as it “served to draw attention to a large number of most interesting differences between the sexes, and, even if it prove to be a fiction, it has done much good in bringing before us an array of important facts in regard to differences in secondary sexual characters”. As to the theory itself, it “meets with fatal objections at every turn” (Morgan 1903). For Morgan, the key to sexual differences was to be found in internal (hormonal) factors—a view that was taken up by some major histories of biology of the early twentieth century (Ràdl 1913; Nordenskjöld 1920; quoted by Cronin 1991, p. 50–51).

In the early twentieth century the scientific climate changed rapidly. Mendel’s laws of particulate genetics were rediscovered, and this paved the way for development of the science of population genetics. Basic principles and tools such as the principle today known as the Hardy-Weinberg distribution were developed (the relevant papers were published in 1908), and major figures such as R.A. Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane and Sewall Wright began to develop theoretical connections between genetics and evolution by natural selection. Eventually information and insights from genetics, paleontology and ecology would be gathered together into a broad view of evolution that was termed the Modern Synthesis (Mayr and Provine 1980).

There is a common claim that the question of sexual selection was largely ignored during this period by leading evolutionary biologists such as Theodosius Dobzhansky and G.G. Simpson. The great emphasis was always on the effects of natural selection. At most, secondary sexual signals which could not be explained as due to competition among males, such as antlers, were seen as identity signals of species, to prevent hybridization: the peacock’s tail would tell the peahen that this male was a conspecific.

In fact, this common claim can be seriously challenged. First there was continuous study of sexual selection in the field of experimental evolution. For instance, the entomologist Frank E. Lutz (1879–1943) published on “the effect of sexual selection” (1911). He worked at the time at the Carnegie Institute’s Station for Experimental Evolution, under the head of Charles B. Davenport. Lutz argues strongly in favor of female choice. “The basis upon which these flies discriminate against ultra-veined individuals when choosing a mate is a matter for further study. There is an elaborate ‘courtship’ in which the flirting of the wings in front of the prospective mate plays a large part. It seems as though a choice were made on the basis of sight, but I doubt whether that is the case. However, there is no doubt of the choice. It is a clear case of the undoing of artificial selection by sexual selection.” (Lutz 1911, p. 37).

Secondly, as noted by Erika Milam (2010), Theodosius Dobzhansky and his colleagues extensively worked on mate choice (especially male choice) in their studies on reproductive isolation in drosophila.

3.2 Beauty for Beauty’s Sake? R. A. Fisher and the Runaway Model

Traditionally depicted as the sole major exception to the general neglect surrounding sexual selection, the geneticist and statistician R. A. Fisher (1890–1962) also played a key role in shaping the terms of the Darwin-Wallace debate. Fisher criticized Wallace’s idea that animals do not show any preference for their mates on account of their beauty, and that female birds do not choose the males with the finest plumage. He also revived Darwin’s idea of beauty for beauty’s sake and developed it into what came to be known as the “runaway” model. Oddly, Fisher, an early pioneer in the field of applied mathematical statistics, did not construct a mathematical model of the process, but his verbal description and discussions became the basis for others to take up that challenge. Fisher provided a more precise verbal statement of an effect perhaps hinted at by Darwin: essentially, a positive feedback mechanism.

In a first paper published in 1915, Fisher rejected Wallace’s argument against aesthetic choice as weak: 1/ because of our necessary ignorance of the motives from which wild animals choose between a number of suitors; 2/ because there remains no satisfactory explanation either of the remarkable secondary sexual characters themselves, or of their careful display in love-dances, or of the evident interest aroused by these antics in the female; 3/ because this objection is apparently associated with the doctrine put forward by Wallace that the artistic faculties in man belong to his «spiritual nature» and have come to him independently of his animal nature. But, Fisher acknowledged, the strongest point in Wallace’s objections was that Darwin had left unexplained the origin of the aesthetic sense in the lower animals.

In 1930, Fisher gave a succinct summary of the disagreement between Darwin and Wallace in the following terms:

The theory put forward by Darwin to account for the evolution of secondary sexual characters involves two rather distinct principles. In one group of cases, common among mammals, the males, especially when polygamous, do battle for the possession of females. That the selection of sires so established is competent to account for the evolution, both of special weapons such as antlers, and of great pugnacity in the breeding season, there are, I believe, few who doubt … (Fisher 1930, p. 131)

At first sight, Fisher’s account is in full acceptance of the first mechanism identified by Darwin, namely male-male competition. But, at the same time, one can feel the influence of Morgan’s hormonal creed in his interpretation of male-male fights: it has become especially clear, according to Fisher, that male-male competition is now beyond doubt, “especially since the investigation of the influence of the sex hormones has shown how genetic modifications of the whole species can be made to manifest themselves in one sex only” (p. 131).

For the second class of cases, Fisher continued, for which the amazing development of the plumage in male pheasants may be taken as typical, Darwin put forward the bold hypothesis that these extraordinary developments are due to the cumulative action of sexual preference exerted by the females at the time of mating. (p. 131)

Here, Fisher isolated the second factor (intra-sexual selection) from the first one, showing that what Darwin had unified under the general head “sexual selection” should be clearly divided into two different factors. Fisher continued:

The two classes of cases were grouped together by Darwin as having in common the important element of competition, involving opportunities for mutual interference and obstruction, the competition being confined to members of a single sex. To some other naturalists the distinction between the two types has seemed more important than this common element, especially the fact that the second type of explanation involves the will or choice of the female. A. R. Wallace accepted without hesitation the influence of mutual combats of the males in the evolution of sex-limited weapons, but rejected altogether the element of female choice in the evolution of sex-limited ornaments. (Fisher 1930, pp. 131–132)

We see here how Wallace’s stance is clearly divided in two parts: acceptance of male-male competition; rejection of female choice. But Fisher raises several objections against Wallace:

-

a.

As Argyll convincingly argued, the hypothesis of protective colouration during brooding is not sufficient;

-

b.

Wallace made errors in assuming that “the effect of selection in the adult is diminished by a large mortality at earlier stages” (Wallace 1889, p. 296). Fisher argues that “if one mature form has an advantage over another, represented by a greater expectation of offspring, this advantage is in no way diminished by the incidence of mortality in the immature stages of development, provided there is no association between mature and immature characters”.

In conclusion, Fisher suggested that Wallace’s reluctance to accept Darwin’s female choice was clearly deriving from his “conviction that the aesthetic faculties were a part of the ‘spiritual nature’ conferred upon mankind alone by a supernatural act, which supplies an explanation of the looseness of his argument” (p. 134).

Fisher’s approach to female choice is original, in that he admits that “with respect to sexual preference, the direct evidence of its existence in animals other than man is, and perhaps always will be, meager” (p. 135). But at the same time, he suggests this should be approached with an evolutionary eye: “the tastes of the organisms, like their organs and faculties, must be regarded as the products of evolutionary change, governed by the relative advantage which such tastes may confer” (p. 136).

This leads Fisher to formulate his idea of a runaway model. The question Fisher posed was: why should a peahen prefer to mate with the peacock with the most splendid tail? His model says: because it’s fashionable. Other females also choose the males with the most impressive tails, so if her sons inherit the genes for a splendid tail they will get to mate more frequently, and their genes will spread in the population. But how does the fashion get started? Fisher suggested that, initially, a slightly larger tail may have conferred some minor selective advantage, so that, by natural selection, the genes of females mating with a peacock with a larger tail may have been somewhat favored. With time, though, the main advantage became the fact that more females mated with males with larger tails and the increased number of matings in itself would lead to the greater fitness of large-tailed males. As Fisher noted, this becomes a “runaway”, an accelerating process, where both the male trait and female preferences for it increase geometrically (exponentially) until the counter-selective disadvantages of an extreme dimorphism lead to a balance between the opposing forces of natural selection and sexual selection. So the process ends in a dynamic equilibrium.

In Fisher’s own words, this 2-step process involves two selective influences:

(i) an initial advantage not due to sexual preference, which advantage may be quite inconsiderable in magnitude, and

(ii) an additional advantage conferred by female preference, which will be proportional to the intensity of this preference. The intensity of the preference will itself be increased by selection so long as the sons of hens exercising the preference most decidedly have any advantage over the sons of other hens, whether this be due to the first or to the second cause (p. 136).

The two characteristics affected by such a process, namely plumage development in the male, and sexual preference for such developments in the female, must thus advance together and so long as the process is unchecked by severe counterselection, will advance with ever increasing speed. In the total absence of such checks, it is easy to see that the speed of development will be proportional to the development already attained, which will therefore increase with time exponentially, or in geometric progression (p. 137).

Fisher’s runaway process stresses the co-evolution between preferences and traits.

What was Fisher’s motivation in developing this insight? It may be related to his early interest in eugenics and his view of sexual selection as a mechanism for ‘racial repair’ and human progress (Bartley 1994).

Fisher’s conjecture was later supported by detailed mathematical analysis (for instance Kirkpatrick et al. 1990). Modeling simulations have shown that the initial selective advantage could be dispensed with, and that the runaway process could begin with an arbitrary signal (O’Donald 1967; Lande 1981; Kirkpatrick 1982). But beyond his formulation of the runaway principle, Fisher’s contribution was important in shaping Darwin and Wallace as standing for two rival evolutionary mechanisms.

3.3 The Good Gene Model

Meanwhile, a rather different kind of explanation for extreme secondary sexual characteristics such as the peacock’s tail was developed. Focusing on the utility of secondary characters, this view is now called the “good gene hypothesis”: it claims that beauty has always, eventually, a purpose. This pan-utilitarian stance has come to be viewed as ‘Wallacean’ although one can find elements of it in texts by Charles Darwin or his grandfather Erasmus Darwin. For instance, in the passage from the 1844 Essay quoted above, Darwin refers to the fact that “the most vigorous and healthy males… must generally gain the victory”—that is, the song, beauty or power of courtship could serve as a signal of a vigorous and healthy male. Similarly, Erasmus Darwin (1794, t. I, p. 503) stated: “The final cause of this contest amongst the males seems to be, that the strongest and most active animal should propagate the species, which should thence become improved.”

A striking extension of the good gene hypothesis was proposed by Amotz Zahavi (1975, 1977; Zahavi and Zahavi 1997) and came to be known as “the handicap principle”. The basic idea is a counter-intuitive one, and it caused much controversy. According to Zahavi’s principle, odd or costly features like the peacock’s tail become subject to adaptive explanations. Being able to survive and function while encumbered with the cost, or handicap of an extreme sexual dimorphism, such as the peacock’s tail or the heavy antlers of the male elk, or elaborate display behaviour in itself serves as a signal of superior genes in a mate. This proposal aroused immediate negative reactions among many, but with time, it has come to be seen as a real possibility, partly because of the appearances of mathematical models indicating how it might work (Pomiankowski 1987; Grafen 1990), so the handicap mechanism of Zahavi can no longer be dismissed. It has fostered the rise of the new field of signal theory, now become a sub-branch of sexual-selection theory (Maynard Smith and Harper 2003). Zahavi has offered an elegant solution to the riddle of female preference for exuberant traits: a question that Darwin had not asked, “why waste attracts mates and deters rivals” (Zahavi and Zahavi 1997, p. 38). And yet the feeling of exuberance in front of sexually-differentiated traits, still remains a strong argument in favour of the Fisherian runaway process. Interestingly enough, Zahavi, while probably being the most prominent neo-Wallacean today, does not claim this. There is only one reference to Wallace in Zahavi and Zahavi (1997, p. 44): “Wallace, in his argument with Darwin over sexual selection, proposed that the main function of male showing off is species recognition.” Accordingly, Zahavi distinguishes two kinds of natural selection: utilitarian selection, which favors straightforward efficiency; signal selection, which results in costly features and traits that look like “waste”. In other words, he recasts Darwin’s sexual selection as the difference between utilitarian and signal selections. The only difference between signal and sexual selection is that the former is much broader than the latter, including all signals, not just those affecting potential mates or sexual rivals.

This distinction clearly raises the question of the meaning of “utility”. Darwin had commented in the Origin “on the protest lately made by some naturalists, against the utilitarian doctrine that every detail of structure has been produced for the good of its possessor”: “They believe, Darwin claimed, that very many structures have been created for beauty in the eyes of man, or for mere variety. This doctrine, if true, would be absolutely fatal to my theory. Yet I fully admit that many structures are of no direct use to their possessors.” (1859, p. 199). So Darwin, at least in the Origin, did not believe that beauty for beauty’s sake was compatible with his natural selection theory. So let’s take a difficult textbook case: the famous peacock tail. The good gene model refers to the selection of characteristics such as ‘vigor’, so its supporters ask if the peacock’s tail could be, somehow, a signal of greater fitness—the ‘honest signal’ hypothesis. Perhaps peacocks with longer tails are also healthier or more fecund? The motivation for this hypothesis was no doubt a desire to uncover something that conventional natural selection could work on, and it also has the advantage of immediately suggesting experimental and field studies. In genetic terms, the basic component here would be a linkage disequilibrium between the conspicuous signal (as in the peacock’s tail) and other, adaptive physiological features, so that the signal can serve as a proxy for another feature that is in fact the subject of natural selection.

It was found experimentally that, given a choice, peahens evidently preferred peacocks with bigger, more brilliant tails (Petrie et al. 1991), and that the offspring of peacocks with larger, more brilliant tails were healthier in various ways, or in any case tended to survive and produce more offspring (Petrie 1992,1994; Moller and Alatalo 1999). However, there has been a recent debate, initiated by a report of study over several years of feral peacocks in which there appeared to be no preference for mating with males with longer trains (Takahashi et al. 2008; Loyau et al. 2008). This has triggered the claim that the “poster-child” example for sexual selection was actually flawed (Roughgarden 2009). Further examinations of this question have concluded that the situation is complex. Another recent study found that males with smaller, less decorated tails are chosen less often as mates but above a low threshold there appeared to be no advantage to having larger, more decorated tails (Dakin and Montgomery 2011). However, it is possible that part of the explanation for these somewhat disparate results from different groups may be found in a study by Loyau’s group, which found a correlation between mating success and the iridescence, or structural colour of the peacock’s tail (Loyau et al. 2007). Females may be responding to the quality of the structural colour (which was not measured in the other studies cited), more than to the size or number of eyespots in the tail (On the “peacock tale”, see Cézilly, this volume).

Potential complexities of this kind of indirect selection could also arise through the intricacies of pleiotropic pathways and linkage disequilibrium, as suggested by a study by Hale et al. (2009). They found experimentally that (1) male peacocks with longer trains tended to have more diversity in their major histocompatibility complex (MHC), generally considered to signify superior immune response to diseases; and also that (2) females preferentially mate with males with longer more elaborate trains. However, in their multivariate analysis of data from a captive population, they also found that, statistically, peahens lay more and larger eggs for males with a more diverse MHC but not necessarily for males with longer trains. Thus, in this case the linkage disequilibrium, if it exists, may be with some other signaling feature or features beside the train. (Again, though, this study did not attempt to monitor iridescence, or structural colour features of the males’ tail feathers.)

4 Concluding Remarks

This paper endeavored to give a detailed overview of the debate between Darwin and Wallace: we have differentiated the motivations and views of the founders of the evolutionary paradigm. But beyond the two men Darwin and Wallace, this paper also gave an opportunity to analyze some conceptual issues between natural and sexual selection. It is often argued that sexual selection and natural selection do not contradict each other, but our study of the Darwin/Wallace controversy reveals that from an historical point of view, this seeming harmony between all types of selection is illusory. In any case, sexual selection was clearly seen as different from and even as contradictory to natural selection.

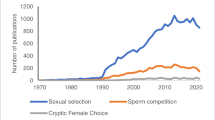

The Darwin-Wallace controversy continues, in a multitude of forms, to fuel new theoretical, experimental and field research. Several papers in this collection still refer to the two major figures, almost ritually, and Darwin and Wallace are energetically hauled over the fuzzy border between good and bad science.

The alleged opposition between the Fisher runaway process and the good-gene hypothesis have been a central concern for many historians of biology. Serving as a grid framing more recent debates, the differences between the Darwinian-Fisherian “sexy son” and the Wallacean-Zahavian “healthy offspring” have been variously rephrased over time, for instance, as “good-taste” vs “good-sense” (Cronin 1991, p. 183). Ridley (1993, p. 143) has likened the conflict to the feud of the Montagues and the Capulets in Romeo and Juliet, and suggested that it was rooted more in personality than in objective science: “Those of a theoretical or mathematical bent—the pale, eccentric types umbilically attached to their computers—became Fisherians. Field biologists and naturalists—bearded, besweatered, and booted—gradually found themselves Good-geners”. The difference would be more one of “scientific temper”: mathematical modeling vs naturalistic fieldwork.

Ultimately, the rhetorical reference to Darwin and Wallace may well serve as an introductory and pedagogical “red herring”: readers are lured into this historical battle of the founding fathers, in order to make the pill of highly abstract theoretical modeling easier to swallow. For instance, Grafen (1990) studied a model of the Zahavi mechanism that explicitly excludes the Fisher process and, in his words, “places Zahavi’s handicap principle on the same logical footing as the Fisher process”. To do this, he required three mathematical appendices, the last of which is 23 pages long and employs relatively advanced tools and concepts (e.g., measures on Banach space) that in general will be familiar only to mathematicians; he then proposes a method of quantifying the relative importance of the Fisher process and the Zahavi principle in both theory and facts (data), and presents a “Fisher index,” to indicate the relative importance of the two processes in a given model or situation. Prum (2010) suggests that the pure Fisher process, without linkage disequilibrium between signal and other adaptive genes, should be considered a null hypothesis in a continuum of models. This may prove to be a fruitful way to look at the landscape of theory.

One can question whether these mechanisms are really mutually exclusive. Indeed, both seem plausible and have support. It might well be that they do both occur in separate cases, or perhaps even simultaneously in a single case, and a realization is developing that the two mechanisms may not necessarily be incompatible.

References

Argyll, GD Campbell, 8th Duke of (1867) The reign of law. Alexander Straban, London

Argyll, GD Campbell, 8th Duke of (1869) Primeval man: an examination of some recent speculations. Strahan & co, London

Bartley M (1994) Conflicts in human progress: sexual selection and the Fisherian ‘runaway’. Brit J Hist Sci 27:177–196

Beddall BG (1968) Wallace, Darwin, and the theory of natural selection. A study in the development of ideas and attitudes. J Hist Biol 1(2):261–323

Beddall BG (1988) Wallace’s annotated copy of Darwin’s. Orig Species J Hist Biol 21(2):265–289

Bock WJ (2009) The Darwin-Wallace Myth of 1858. Proc Zool Soc 62(1):1–12

Bowler PJ (1976) Alfred Russel Wallace’s concepts of variation. J Hist Med 31:17–29

Bowler PJ (1983) The Eclipse of darwinism: anti-darwinian evolution theories in the decades around 1900. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

Bowler PJ (1984) Evolution. The history of an Idea. University of California Press, Berkeley

Bowler PJ (1988) The Non-Darwinian revolution. Reinterpreting a historical myth. The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Brooks WK (1883) The law of heredity. A study of the cause of variation, and the origin of living organisms. John Murphy & Co, Baltimore

Browne J (1995) Charles darwin. voyaging, (A Biography: vol I). Princeton University Press, Princeton

Cronin H (1991) The ant and the peacock. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Dakin R, Montgomerie R (2011) Peahens prefer peacocks displaying more eyespots, but rarely. Anim Behav. doi:10:1016/j.anbehav.2011.03.01

Darwin E (1794) Zoonomia, or, the laws of organic life. J. Johnson, London

Darwin CR (1858) On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection. J Proc Linnaean Soc Zool 3:46–50

Darwin CR (1859) On the origin of Species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. John Murray, London

Darwin CR (1868) The variation of animals and plants under domestication. John Murray, London

Darwin CR (1871) The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. John Murray, 2 vol. London

Darwin CR (1872) The expression of the emotions in man and animals. John Murray, London. (reprinted 2009. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Darwin CR (1874) The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex, 2nd ed. John Murray, London

Darwin CR (1991) The correspondence of Charles Darwin. In: Burkhardt F, Smith S (eds) (vol 7). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Desmond A, Moore J (2009) Darwin’s sacred cause: how a hatred of slavery shaped darwin’s views on human evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston

Fisher RA (1915) The evolution of sexual preference. Eugen Res 7:184–191

Fisher RA (1930) The genetical theory of natural selection. The Clarendon Press, Oxford (Reprinted 1958, New York: Dover Publications).

Flannery M (ed) (2008) Alfred Russel Wallace’s theory of inteligent evolution. The Discovery Institute, Seattle

Flannery M (2011) Alfred Russel Wallace: a rediscovered life. The Discovery Institute, Seattle