Abstract

One of the basic conditions for the European Union (EU) membership is a candidate country’s ability to cope with competitive pressures of the single European market. Given that the Western Balkans economies are in the bottom tier of global competitiveness rankings, joining the EU represents a monumental task. Western Balkan economies lack dedicated institutions tasked with the creation and coordination of trade policy so that within this void, informal actors, such as foreign companies and special interests exert considerable influence. This paper explores the role of government and the private sector (e.g., chambers, individuals, oligarchs) in developing the trade framework, specifically focusing on the role of policy makers, formal and informal networks, and regional bodies in shaping the regional and national trade policy. It pays a particular attention to the regional trade integration as a framework conducive to improving competitiveness in the Western Balkans, against a broader context of compliance with the WTO multilateral trade regime. The paper highlights the challenges facing policy makers in the region in creating a stable and predictable framework for the locally operating companies, and ensuring a level playing field.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The Western BalkansFootnote 1 comprises the economies of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Kosovo.Footnote 2 These economies largely share a common heritage and were once part of Yugoslavia—except for Albania. Despite being a Socialist Republic, the former Yugoslavia maintained some unique features including elements of a market-based economy. Thus, it was expected that the transition to a full market economy would be easier than in other East European countries. However, the breakup of Yugoslavia proved to be complex, marked by conflict and lengthy resulting in a difficult and messy transition for the economies that subsequently emerged. Albania’s path to transition was separate but similar in many respects. As the individual states emerged from the conflict, there was no regional cooperation or evidence of regional trade integration. A clear, strategic foreign policy objective of all Western Balkan countries was to join the European Union (EU) and significant portions of their respective citizenry similarly aspired to the benefits of EU membership. The attractions of EU membership include a better standard of living and higher economic growth. However, as noted by Kaminski and de la Rocha (2003), the EU Stabilization and Association Agreements signed by aspiring EU neighbourhood countries in the Balkans commits them “to upgrading institutions and policies to European standards and governance” while motivating “public support and, thereby, facilitating implementation of structural reforms.” So while many of the institutional and economic policy reforms in the Western Balkans result from political pressures from the EU, the policy of conditionality for EU membership has limited results because there is a large gap between introduction of policies in the Western Balkans and their implementation in this region.

One condition for all Balkan countries for EU membership was regional cooperation. Regional trade integration was initiated by the EU, and in 2000 the Memorandum on Liberalisation of Trade in South East Europe was concluded by all Western Balkan economies. Regional trade integration was achieved in phases starting with bilateral trade agreements and the creation of a network of 32 bilateral trade agreements among the Western Balkan economies. In 2006, the 1993 Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) was revised to support the establishment of a regional trade association in the Western Balkans. Even though this was a single agreement, trade preferences were included from bilateral agreements and were arranged on a bilateral level. The CEFTA 2006 agreement included provisions for creating a free trade zone for industrial goods by the end of 2010. The Republic of Moldova is not geographically positioned in Western Balkans region but is a contracting party of the CEFTA 2006 integration even though the volume of trade between Moldova and the rest of CEFTA 2006 members is very low.

The Western Balkan economies are also trying to integrate into the world economy. An important step in this direction is gaining World Trade Organization (WTO) membership. As shown in Table 4.1, five of the Western Balkan economies are WTO members two are in the process of accession and have observer status. Kosovo has not applied for WTO membership. The WTO oversees the specific multilateral trade regime that must be followed by all WTO members.

The objective of this chapter is to examine the trade policy process in selected Western Balkan economies, taking into account the roles of key domestic, regional and international actors, and the influence of global, bi-lateral, and regional trade regimes on key policy episodes. With rapid globalisation and the importance of international trade and investment for economic growth, countries are under increasing pressure from trade partners and institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and WTO to liberalise, and harmonize policies in order to compete and tap into global value chains. Some have argues that smaller and less developed economies are under greater competitiveness pressures compared with the large, developed ones. By accepting membership in relevant international organizations the Western Balkan economies are similarly under pressure to significantly liberalise their trade regimes and implement significant tariff cuts.

When considering trade policy reforms, the Western Balkan economies have to take into account three main trade regimes: CEFTA 2006; the EU; and WTO. Obligations derived from the membership of Western Balkan economies in all these set the conditions for trade policy adjustment since member countries are not completely autonomous in trade policy creation. Sometimes trade regimes can be conflicting, and their effect on countries competitiveness on international markets can be significant. But these trade regimes set the framework for the operation of domestic and foreign businesses and have significant impact on their competitiveness in both the regional and the global market. In trade policy creation, the Western Balkan economies are also influenced by these companies’ efforts to secure better operating conditions for themselves.

Western Balkan economies have not finished the process of transition to a fully functioning market economies and do not have fully developed economic systems, as demonstrated by European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) research. Their competitiveness on the world market is very weak with no prospect of rapid recovery, demonstrated by World Economic Forum data shown in Fig. 4.1. These economies are becoming severely indebted, and the problem of domestic and international liquidity is an issue. Western Balkan economies are relatively small and highly dependent on exports to international markets and on the inflow of foreign private investments. Specifically Bjelić and Dragutinović-Mitrović (2012) demonstrated on the case of Serbia how conflicting trade regimes influence trade flows, and show that significant trade preference cannot divert trade from traditional trade partners in a long run. The companies operating in these economies while not internationally competitive are highly competitive in the domestic and regional markets. Western Balkan economies have been benefiting from EU asymmetrical trade preferences but as the EU trade regime becomes symmetrical the competitiveness of Western Balkan economies and companies operating in this countries started to decrease (Dragutinović-Mitrović and Bjelić 2013). Generally speaking, the interest of foreign-owned companies operating in the Western Balkans is greater liberalisation, while domestic companies tend to be more protectionist-oriented.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in the Western Balkans is only from those willing to operate in a corrupt and unstable political and economic environment, as illustrated by Perez et al. (2012). But the foreign-controlled enterprises operating in the Western Balkans also exert some informal influence on trade policy creation in the region to provide a better business environment for themselves in the CEFTA 2006 area, and require significant subvention in order to starts its operations.

2 Formal Trade Policy Creation in the Western Balkans

Trade policies embody the strategies pursued by countries in order to regulate its foreign trade and to keep it in line with societal interests. ‘Trade policies refer to all policies that have a direct impact on the domestic prices of tradeables, that is, goods and services traded across national boundaries as imports and/or exports’ (Milner 1999, 93). An economy can regulate international trade with unilateral actions, passing laws on trade matters like customs law, customs tariff law and laws on foreign trade. But as international trade is a transnational business activity, to fully regulate this activity, economies must cooperate between themselves. The main instruments in their joint regulation of international trade are trade agreements (Cooper 1973). It is often mistakenly felt that it is only in state-planned economies that the state has a large impact on trade and the trade regime. In both market and planned economies politicians have designed institutions and implemented policies that interfere with free trade by actively favouring some trade flows and restricting others. This conflict or paradox between theory and practice in market economies has led to extensive literature on the political determinants of trade policy (Brada 1991). Perhaps no area of economics more than international trade displays such a wide gap between what policy makers practice and what economists preach. The superiority of free trade is theoretically founded, yet international trade is rarely free in practice (Rodrik 1995, 1458).

The formal trade policy-creation process in the Western Balkan economies is often ambiguous, non-transparent and contradictory. Often there is no government institution or body focusing on trade policy development and coordination, and when there is one, this state organ usually changes focus with each new government. The responsibility and authority for trade policy creation typically reside at the state or federal level. As shown in Table 4.2, the government department responsible for international economic relations are usually not organised as separate ministries or entities but as a part of ministries responsible for economic affairs. The exceptions in the region are Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the Ministry for Foreign Trade and Economic Relations still exists as a separate ministry at the state government level. Our opinion is that all Western Balkan economies, as small and open economies, should have a separate ministry focusing on external economic relations, especially foreign trade.

Typically trade policy initiatives emanate from the government through laws and by-laws covering trade and draft trade agreements and are subject to parliamentary review and adoption. As standard procedure for most laws, draft legislation is first debated in the responsible parliamentary committee and require a majority vote before being sent to the General Assembly for a decision. Trade-related legislation and agreements are usually debated in parliamentary committees that responsible for economic matters. Sometimes important trade-related legislation is directed to different committees. For example in the case of Serbia, foreign trade law is debated in the foreign affairs rather than the economics parliamentary committee. Increasingly parliaments in the region are adopting the practices of Western Democracies by soliciting the testimony of experts and holding public hearings on proposed legislation to arrive at better informed decisions about technical and policy issues that require specialized knowledge.

Most often, after parliament passes a certain trade-related legislation or agreement, it is the government that executes that legislation. The government is responsible for the implementing regulations based on the law passed by the parliament—directives, regulations and procedures—which provide detailed instruction for complying with the law. Although the ministry that is responsible for trade-related matters (e.g., the Ministry of Foreign Trade or the Ministry of Economy) had responsibility for implementation and compliance, trade policy execution demands cooperation among many different ministries in the government facilitated by special technical bodies including commissions and working groups. For example, the ministry that covers agriculture is in charge of application of sanitary and phyto-sanitary measures in international trade, and their inspectors are present at the border with other border control agencies.

To explain this process, we can illustrate it with an example of the WTO accession process. When a government sends a letter to the Director General of the WTO, expressing its wish to join the Organisation, the process of accession is initiated. For each individual country, the ministry in charge of trade policy plays the main role in the accession process. Usually a subsidiary coordinating organ is established as a commission to focus all efforts towards WTO accession. This subsidiary organ coordinates the efforts of several ministries, but the elected negotiators represent the government at negotiations held in WTO headquarters in Geneva. When the Draft List of Concessions is adopted, the Draft Protocol of Accession is forwarded to the state parliament to be adopted. When the parliament ratifies the accession package, the Director General of the WTO is notified, and the country becomes a WTO member in 30 days from this notification. It is apparent that the national government bears the heaviest burden in the WTO accession process.

Although national trade regimes are unilaterally established with laws and regulations determining tariff schedule and the regulations spelling out non-tariff measures, in today’s world, countries tend to set the conditions of foreign trade in cooperation with other countries—their trade partners. This can be achieved in processes of bilateral, regional or multilateral trade cooperation. The most important instrument of trade cooperation until the nineteenth century was bilateral trade agreements that countries concluded setting the customs duties in their mutual trade at a lower level than the general level of tariff regime defined in tariff schedules. These preferential trade agreements were the cornerstones of the international trade system since they included the most favoured nation (MFN) clause, lowering tariffs from the general tariff regime; thus, this is referred to as the MFN regime. In this way a country lowers its tariffs for trade partners, and these new tariffs are known as conventional tariffs since they are introduced by international agreements (conventions).

In the first part of the following table (Table 4.3), we have presented the trade regime applied by Western Balkan economies; this is set unilaterally by these countries by adopting national tariff schedules. We can observe that nominally Serbia and Macedonia have the most restrictive tariff regimes, measured by the average tariff rate.Footnote 3 This average tariff rate, in the first line of the table, represents the average for tariffs for all products in the tariff schedule. The other two rows represent average tariff rates separately for agricultural products and industrial products. Usually countries have more restrictive tariff regimes for agricultural products than for industrial ones. Apart from Serbia and Macedonia, we see that Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina have significant average tariff rates for agricultural products. Bosnia and Herzegovina has a significant average tariff rate even for industrial goods.

But if we observe a tariff regime using the weighted average tariff rate, where we use trade in specific products at certain tariff rates as weights, we can see that Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro have the most restrictive tariff regimes, especially for industrial products. This is even more obvious if we observe the data on the maximum tariff that countries apply, which in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina goes up to 595 %, knowing that this country has around 3 % of all tariffs expressed in non ad valorem form.Footnote 4 Serbia has a very restrictive regime for agricultural products, measured by a weighted average tariff rate, and a significant number of products with tariff rates above 15 %, around 13 % of products in Serbia tariff schedule.

Liberalisation from a general tariff regime—today usually the MFN regime that the country unilaterally adopts—can be achieved in two dimensions: regional trade liberalisation and multilateral trade liberalisation. Regional trade liberalisation is more usual and comprehensive since similar economies are bound in the trade integration processes. Countries in the region are similar not only economically but also culturally, linguistically and consumption-wise. For these reasons regional trade integration sometimes tends to be deeper and wider than multilateral trade liberalisation. Today every region in the world has its regional trade integration; in some regions there are several regional trade integrations. But one integration always dominates, and there is some initiative that links entire continents in trade integration.

In the Western Balkans, regional trade integration commenced with the signing of the CEFTA 2006 agreement. The revised CEFTA agreement from 2006 included all trade preferences negotiated on a bilateral basis between Western Balkan economies in the framework of the Memorandum on Trade Liberalisation in South East Europe, signed in 2000. CEFTA 2006 integration regulates only intra-regional trade since it represents a free trade area for industrial goods and agricultural products. Services will soon also be included in the CEFTA 2006 framework. There has been some discussion that CEFTA 2006 may become a customs union, meaning that member economies adopt a common external tariff to be applied in trade with all countries outside CEFTA 2006. This would mean the deepening of trade integration in CEFTA 2006, but in practice this is not realistic as CEFTA 2006 is only a provisional integration as all members tend to be EU members.

Trade relations of individual CEFTA 2006 economies with non-members are not regulated by the CEFTA 2006 agreement so these economies regulate these relations on their own by creating different regimes. A country can become a member of different regional trade integrations if this integration is at a lower level—like the free trade area. But the dominant trade integration in Europe is the EU, and countries of the Western Balkans are set to become members. When a country joins the EU, it has to relinquish all other trade regimes; it especially has to discontinue membership in all other preferential regional trade integrations since EU is a trade block integrated at a higher level of regional trade integration with a common trade policy. This was the case for the majority of Eastern European economies in 2004, for Romania and Bulgaria in 2007 and Croatia in 2013.

The countries of the Western Balkans can now regulate their trade relations with CEFTA 2006 non-members on their own, but once a part of EU, they must follow a common EU trade policy and apply an external EU tariff schedule. The trade agreement that Serbia has with the Russian Federation, which is quite generous in trade preferences, will be terminated when Serbia joins the EU; this is an example of the sacrifice that countries must make to become EU members. Serbia will, from that day forward, apply the EU trade regime towards the Russian Federation. The EU is a regional trade integration that has a joint external trade regime, and it is the important element that defines the layers of trade policy that EU members apply. There is some discussion that the Western Balkan economies could adopt the EU customs union for trade in industrial products even before they achieve formal membership, since their individual tariff schedules are very diverse (Kathuria 2008, 67), but this could obstruct trade between Western Balkan economies with third countries especially if EU membership does not come in the foreseeable future, as in the case of Turkey.

Apart from regional trade liberalisation, the other very important process in the world economy is multilateral trade liberalisation, within the World Trade Organization framework. When a country becomes a member of this global body, it effectively relinquishes aspects of its trade sovereignty in order to receive the collective benefits of membership. One basic obligation of membership is defining a list of trade preferences for other WTO members. These preferences establish the bounded tariff rates which are the maximum tariffs a country can set in its trade relation with other WTO members. In this way defined market access for all WTO members is guaranteed by the WTO, and a specific multilateral trade regime is created (a WTO-bounded trade regime). WTO has two mechanisms to ensure the application of its rules: Trade Policy Review Mechanism and Dispute Settlement Mechanism. The former is a method of surveillance by the organisation of its members’ trade policy. The members have to incorporate all WTO rules in their trade systems, and their tariff schedules (applied tariff regime) must be in compliance with their WTO-bounded trade regime. If some members feel that their trade interests are jeopardised by actions of other WTO members, they can instigate a Dispute Settlement Process in the WTO that examines whether there was a breach of WTO obligations.

In this way more conventional tariffs are applied than the autonomous tariffs set unilaterally by each country. This demonstrates the influence of international organisations on international trade policy of their members. The WTO-bounded trade regime is usually set during the country accession process and further liberalised during the rounds of multilateral trade negotiations. Western Balkan countries have recently joined WTO or are in the process of WTO accession. During this process, the key phase is negotiations on market access where the acceding country must bind its tariffs. There are no clear rules of accession, so each country must negotiate its own ‘entrance ticket’. WTO membership brings certain costs linked to modernisation and harmonisation of various institutions directly involved in the conduct of foreign trade policy. But the impetus to join WTO lies in the benefits of membership. The main draw is improved market access for export products due to the WTO multilateral trade regime. But some researchers have discovered that there are limits to how far and how much the agreements help. WTO membership cannot address problems originating in poor domestic supply response, terms of trade changes or exogenous shocks. The accession itself may not even open up new markets for the acceding countries as incumbents are not expected to provide new concessions to them (Drabek and Bacchetta 2004, 1122).

The Western Balkan countries that are WTO members like Albania, Croatia, Macedonia and recently Montenegro have bound their tariffs in the WTO framework. Average bounded tariff is around 5–7 %. The regime is more restrictive for agricultural products, especially in Macedonia and Croatia, where the tariffs are 13 % and 11 %, respectively. The average tariff for industrial products is in the 4.3–6.6 % interval. All Western Balkan economies have bounded all products in its tariff schedule, as shown in Table 4.3. Even Western Balkan countries that are in the process of accession to the WTO are observing the multilateral trade regime and are influenced by it. Serbia’s 2009 Law on Foreign Trade Business, Article 1 stipulates that ‘this law regulates foreign trade business in accordance with WTO rules and EU regulations’.Footnote 5 It is a rule that countries acceding to WTO cannot make significant changes in their trade regimes, but this rule is not observed in all Western Balkan economies.

3 Competitiveness of Western Balkan Economies and Informal Trade Policy Creation

The unilateral, regional and multilateral trade liberalisation often creates different trade regimes. Sometimes these regimes can diverge, and countries have to work actively to align them. For companies, these regimes represent the frameworks in which they operate and can significantly impact their international as well as domestic competitiveness. In the global arena, companies are becoming more influential actors as their economic grip on international trade is rising. Large transnational companies (TNCs) are main actors in international trade and the biggest sources of private capital that moves across borders. With this economic power they are able to exercise greater political power and to influence policy creation in many countries. Thus the formal process of trade policy creation is not completely relevant as trade policy creation globally, but especially in the Western Balkans, is deeply influenced by informal actors such as foreign companies and local pressure groups. This leads to the creation of a framework of trade policy, which is biased to the interests of certain pressure groups. In a sense, trade policy in the Western Balkan countries is shaped more by economic interests of large capital than by the state institutions in charge for this process.

The concept of country competitiveness, or macroeconomic competitiveness—although at times disputed—is now accepted by the majority of economists. This concept was developed from a microeconomic concept that shows the rivalry of companies on the market. We have to acknowledge that countries today compete for resources, markets and investments. These economic rivalries on international markets create their geostrategic dimension. The theoretical background for macroeconomic competitiveness was developed by American business economist Michael Porter. One important postulate of his theory of competitive advantage was that competitiveness of companies operating in one country significantly influences the competitiveness of that country and vice versa—the macroeconomic competitiveness of a country influences competitiveness of its companies (Porter 1990).

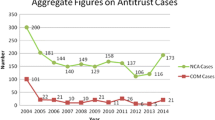

Western Balkans economies are in the bottom tier of the global competitiveness league compared to most other economies in the world, according to the analysis by the World Economic Forum (WEF). One of the most competitive countries in the region is Slovenia, which has been an EU member since 2004. The majority of Western Balkan economies have recorded decline in their global competitiveness rankings in the observed period 2007–2011. Most of them fell below the 70th position among 130 observed economies in 2011 in a World Economic Forum sample. Only Montenegro and Macedonia show rising ranks in the period 2007–2011. With rapid growth, Montenegro became the most competitive economy in the Western Balkans in 2011, well before Croatia, the economy set to become the newest EU member. The Croatian and Serbian economies experienced the largest fall in competitiveness in the last years. Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are at the bottom of the regional competitiveness list.

The causes of low competitiveness of Western Balkans economies lie not only in low economic performance but also in the political, social and legal frameworks in these countries. The WEF has pointed out that countries in the Western Balkans have weak and undeveloped state institutions and that the performance of these institutions is one of the main factors for low competitiveness. Institutions in these countries are wracked by corruption. All Western Balkans countries show weak results by WEF ranks, which represent a subjective estimation of managers in these countries, but similar results are indicated in the objective statistical data by organisations researching corruption, such as Transparency International (Fig. 4.2).

Competitiveness factors for Western Balkan economies in 2011 (Source: World Economic Forum, Internet, http://gcr.weforum.org/gcr2011/)

One of the lower ranked competitiveness factors is infrastructure—testimony that infrastructure in the Western Balkans is underdeveloped—and this significantly influences economic growth and trade perspectives. Infrastructure is a prerequisite for improved economic development. There have been some moves to improve infrastructure, especially in the larger economies of the Western Balkans, like Croatia and Serbia. But sustained economic development is dependent today on the improvement and application of technology in business processes. The development of technology is connected to innovation, which is very low in these economies. Without investment in technology and stimulation of innovation, Western Balkan economies cannot improve their international competitiveness in the long run.

Companies operating in the Western Balkans are, like the countries in which they operate, generally not competitive on the global level. The structure of these companies is very diverse as their host countries are undergoing a process of transition to a full market economy. There are still large—in the number of employees—state-owned companies that do not have good prospects even in the national market, as well as small and vibrant private companies that are very efficient but without enough potential to compete at a global level. But there are a rising number of foreign-controlled enterprises in the Western Balkans as a result of the processes of globalisation and trans-nationalisation of the world economy. As Western Balkan economies lack indigenous capital, they try to attract foreign capital to promote exports and economic growth. But many foreign investments are oriented towards servicing national or regional markets of a country where these affiliates operate.

Western Balkan economies are all countries in transition with weak state institutions. Corruption is endemic and very possibly affects policy makers as well. Various interest groups have an interest in formatting state trade policies. In this part of the chapter we will acknowledge these informal trade policy actors and try to point out their methods and inter-linkages. The most important informal actors in trade policy creation are companies.

Large domestic companies are usually state-owned monopolies dependent exclusively on a national market; they tend to pressure the government to adopt protectionist policies—restrict imports and limit competition in the domestic market. The main instrument of pressure is the large number of their employees, who are also the voters in elections. One example of this is the Serbian steel producing company, which was taken over by the Serbian government last year before the national elections, when a US steel company drew back from its Serbian investment. In large state-owned companies that fall into the category of public state enterprise, the politicians are usually also the managers appointed by the national government. They also put pressure on the government to raise tariffs to protect these companies. Even if these companies are natural monopolies, they operate with a loss since they serve as unofficial sources of political party funding.

Even private companies that operate solely on the national market since they are not competitive abroad can pressure the government to restrict international trade because they only supply consumers in this market. These restrictions are hard to introduce with a tariff rise, since they cannot be justified on the world scene, so today they use nontariff barriers. An example from our survey of opinions in Serbia was the adoption of the Law on Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs).Footnote 6 Although there are many conflicting views on GMOs, the WTO principle is that country members cannot obstruct trade in these organisms since there is still no sound scientific proof that they may be dangerous for human health. Serbia adopted a law in June 2009 banning production and trade in GMOs. This law was in conflict with WTO rules, and Serbia as a country in accession had an obligation not to change its trade regime significantly while acceding to the WTO. There are some indications in a US demarche to the Serbian Ministry of Agriculture from June 29, 2009, that the law was adopted under the influence of Serbian producers of soya and soya products to guarantee the consumption of locally produced soya,Footnote 7 which is also produced in a significant degree from GMO seeds. The main instrument of pressure on the government concerning trade policy is in the form of donations that these companies give to political parties.

On the other side, there are many domestic companies that are in the trade business—usually imports for domestic consumption—and they push for a more liberal import policy. Since their influence on trade policy tends to be very strong, they are often referred to as the ‘import lobby’. But this liberalisation is limited to only these companies since even with the liberal import regime in some sectors, they obstruct the entrance of competitors into their market. Lack of competition even in the import business creates high prices that Serbian customers are obliged to pay for foreign goods; these goods can be a few times more expensive than in their market of origin. These extremely high prices are specific to the clothing sector and are not influenced by customs and tax duties but rather by a high wholesaler’s margin. The government is reluctant to deal with these monopolies—by liberalising total imports of monopolised products, for instance—since these companies are often connected to government officials, or else, owners of these companies pay a premium to politicians to be ‘protected’ on the market.

Since the Western Balkan economies by and large lack dedicated institutions tasked with the creation and coordination of trade policy, in this void informal actors, including foreign companies and special interests, exert considerable influence. One can posit that the economic interests of large capital in fact define the trade policy of these countries with consequences in the prospects for improving competitiveness and stimulating growth. Foreign companies using foreign direct investment establish a company that is incorporated and functions under the law of the host country, but it is economically dependent on its parent company. The region is becoming especially interesting for big international companies as it approaches membership of the European Union. These companies bring fresh capital and new technologies but can also influence state institutions. They would like to profile the trade policy of host economies to have greater profit-making ability.

Concerning the inflow of FDI, Western Balkan economies have been active in buyer-driven production chains but have not yet managed to make a significant transition towards producer-driven supply chains. During the initial phase of the transition, most Western Balkan countries relied on unskilled labour–intensive exports associated with buyer-driven production chains in clothing and furniture, in which global buyers create a supply base without direct ownership (Kathuria 2008, 42). This has a small impact on value-added in Western Balkan economies and does not represent significant integration into the global economy. Exports are all about transferring more of the local value-added abroad. However, the business environment is not favourable for attracting respectable foreign investments; rather, the capital that enters these countries is for speculative purposes.

The question that remains is how companies—domestic or foreign—exert influence on trade policy creators, that is, the government? One main channel of influence is the political parties with representatives in parliament or the government. Usually large companies finance the activities of the parties, especially during the election campaigns. This finance can go through official or unofficial channels, and is known as ‘soft money’. Usually domestic firms (including companies incorporated in one country but under foreign control) employing a substantial number of people can use these jobs as a pressuring instrument—big layoffs create political pressure, as workers are also potential voters. Sometimes companies use bribes to influence trade policy creation. In the Western Balkans it is not rare for companies to bribe a civil servant to act in they interest. These instruments of influence tend to restrict the trade regime through escalation of tariffs, but since these escalations are limited by WTO international obligations, the restrictions are made through nontariff barriers. In the global economy countries compete for market access and access to resources, and they take actions that favour their companies at home—through public procurement preferences, and abroad—through subventions and other aids. In literature, these government actions are known as strategic trade policy.

A main characteristic of the world economy today is the monopolisation of global markets through capital concentration and the appearance of large global companies known as transnational corporations. These companies have higher yearly sales than the GDP of many countries in the world. These companies can influence not only countries where they are registered (home countries), but also countries where they have established their affiliate companies (host countries). TNCs tend to influence trade policy creation in these countries to create greater possibilities for profit generation. The target of their influence can also be international intergovernmental organisations where significant global trade rules are passed. Their interests are also protected and communicated by their global organisation, the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and some informal groups such as the World Economic Forum, which serve as instruments of influence to countries and international intergovernmental organisations (Bjelić 2003, 84–88) (Fig. 4.3).

Transnational corporations’ trade policy influence pyramid (Source: Bjelić 2003, 84)

Some authors have defined contemporary international relations through the model of triangular diplomacy consisting of three factors: competition of companies for market share, negotiations between companies and states, and competition between states with trade policy as a main instrument. In this way global companies can even influence international politics (Stopford and Strange 1991).

These companies can also influence government at lower levels—as in the functioning of government agencies—and in international trade where the customs procedures are specific. Usually trade preferences are connected to the domestic origin of the export products. To prove the domestic origin, a company must provide a certificate of origin from the exporting country’s customs. Only with this document can the company benefit from a preferential tariff regime. But in countries where the system of rules of origin is not significantly developed and where there is endemic corruption, companies can obtain these certificates for products that do not have local origin. An example is the re-export of sugar from Cuba through Serbia to the European Union. A Serbian company obtained a certificate of origin for cane sugar even though in Serbia sugar is produced from beet. The certificate was a pass to use the preferential tariff rates given to Serbia by the EU based on the bilateral agreement. When EU customs established there had been a breach of rules of origin, the export of sugar from Serbia to the EU was banned.

Citizens of Western Balkan countries favour a liberal trade policy since they are customers and prefer a larger variety of goods and lower prices that only foreign competition can ensure. But as employees, they would like their jobs and salaries to be secure, and from that angle they fear foreign competition for their domestic employers. Economic theory suggests that if an imported good is produced in a labour-intensive manner, a worker in an economy facing fixed international terms of trade will favour an import duty, while a capitalist will favour free trade (Baldwin 1989, 120). The social concerns model explains trade policies mainly by the government’s concern for the welfare of certain social and economic groups and by its desire to promote various national and international goals (Baldwin 1989, 126). Some authors argue that trade bureaucrats lead in trade policy creation (Finger 1984, 745). All these interests must be considered when a country defines its trade policy. Any changes in the present trade regime can significantly affect the interests of diverse stakeholders. Policy implementation is frequently fragmented and interrupted, and policy change often requires difficult adjustments in the supporting stakeholder coalition, changes in the structures and rules of familiar institutions, and new patterns of interaction (Crosby 1996, 1405). Free trade does not exist today; rather, there are different trade regimes. These regimes need to be stable over a longer time so companies can make proper long-term investment decisions. However, one trade regime that will persist in the longer run is the EU trade regime.

4 EU Membership of Western Balkan Economies and Trade Policy Reform

The biggest change in trade policy for Western Balkans economies will come with EU membership. Many changes in economic policies have already resulted from the economic and political influence of the EU, in some cases through conditionality and other requirements. This ‘pull or push’ policy has had limited effect since there is often a considerable gap between the introduction of policies in the Western Balkans and their implementation.

The EU’s trade policy powers are vested in its institutions. Member countries cannot set its trade rules but rather have to follow the common EU external trade regime. The Common Trade Policy of the European Union was created in 1957 with the signing of the agreement establishing the European Economic Community. The main institutions in the EU common trade policy-creation process are the Council of the EU and the European Parliament. But all the legal initiatives in trade policy come from the European Commission, which, after these initiatives are adopted by the council and the parliament, also implements the rules. The focus organ that coordinates all the activities in the EU concerning trade policy is the 133 Committee (Bjelić 2003, 129). Even though this committee is a body of the council, some researchers feel that it has significant influence on common trade policy creation in the EU without transparent procedure, especially after the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty (Woolcock 2010, 7). There are some, even in the EU, who say the 133 Committee is the real power and decision-making centre for the European Union’s commercial policy.Footnote 8 The members of the 133 Committee are trade experts who prepare decisions for the council, which adopts them without much debate. European policy making is not a depoliticised process wherein the exchange of functional expertise and information stands central; political cleavages considerably affect the day-to-day policy network among Euro-level bureaucrats, politicians and societal interests. In the European Parliament, for example, three groups can be identified in connection to trade policy creation: Prosocial Europe Coalition, Proecology Coalition and Progrowth Coalition (Beyers and Kerremans 2004, 1146).

One of the basic conditions for EU membership is the candidate country’s ability to cope with the competitive pressures of the single European market. Given that the countries in the Western Balkans are at a lower level of global competitiveness, the EU has designed a transitory process for all Western Balkan countries to lower their tariff regime towards the EU. Since 2000 the EU has unilaterally granted a special trade regime to these economies in the form of Autonomous Trade Measures (ATMs), which are asymmetrically biased towards Western Balkan economies. Also these countries must use the period before EU accession to significantly improve their competitiveness.

Regional trade integration in the Western Balkans created by a revised Central European Free Trade Agreement from 2006 (CEFTA 2006) is a transitory integration since all countries in the Western Balkans are moving towards EU membership. But CEFTA 2006 can be an effective framework for these economies to build competitiveness—individual as well as regional—and to prepare them for future EU membership. Western Balkan economies are at a similar level of economic development, with similar economic and political legacies and with many cultural affinities. In the policy arena, the area needs regional coordination of trade policy with formal frameworks and institutions that can improve competitiveness at the regional level. Therefore, the CEFTA 2006 trade regime could not only stimulate intraregional trade but also allow member economies to use their trade potential in relation to the EU—the EU has a very favourable trade regime towards Western Balkan countries, as well as the diagonal accumulation of origin to prepare for their integration into the single market.

But the economic cooperation of Western Balkan countries has some political boundaries. Greater economic cooperation sometimes requires greater regional coordination of policies, and some groups see this process as a new political reunification in this region. Regional trade integration in the Western Balkans has been initiated by the EU; sometimes the only impetus for this regional cooperation is the prospect of EU membership.

While Western Balkan economies hesitate to cooperate further, illegitimate businesses and representatives of large capital have good regional cooperation. Western Balkan economies have a large share of GDP from the so-called grey zone. Many employees are not officially registered, so not all turnover is reported for tax evasion purposes, and many goods are imported unofficially. The trade between Western Balkan economies still occurs in unregulated channels while crime organisations cooperate at the regional level. This is due to the low level of political cooperation of Western Balkan countries and the lack of coordination of different national policies in combating smuggling and illegal cross-border trade in the region. This is the area where traditional trade policy has no effect and where there are other actors and stakeholders. Trade is still largely influenced by political factors in the Balkans. A typical example is the trade relations between Serbia and Kosovo, which are complicated by Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence and Serbia’s refusal to engage in dialogue on trade matters with institutions in Priština (Bjelić et al. 2012).

The EU is a heterogeneous mix of economies at different levels of development and with diverse competitive advantages, but operating within the EU common trade regime, is something the Western Balkan countries will have to adopt as part of the EU membership package. These economies will have to find their trade niche within the single European market and learn how to increase competitiveness as EU members and contribute to EU competitiveness. Free trade does not exist in the global economy; it is all about regulated trade and the understanding of trade regimes. The EU is a global trade player that resorts to a large number of protectionist measures, which distort global trade flows. A typical example is EU’s Common Agriculture Policy (CAP), which was set primarily to ensure high prices to European producers of agricultural products. The European agricultural market was protected against the large influx of foreign agricultural products by tariffs and nontariff barriers that offset the difference between European and world prices. Due to subventions, which are one of the main instruments of CAP, instead that EU import most agricultural products, if there were free trade, the EU produced more agricultural products than consumers at home and abroad needed and EU was left with the surplus. Subsidized prices in the EU are higher than both world prices and prices that would be set in the European market without imports. But CAP has significant influence not only on the EU agricultural market but also on international trade in agricultural products. Subsidized European prices push down world prices whereby claims on higher subsidies grow because of the increase in the gap between world and European prices. There is no logical economics-based explanation for this since costs for European consumers and taxpayers surpass benefits for agricultural producers (Krugman and Obsfeld 2003, 198–99).

One trade regime that influences the Western Balkan economies’ competitiveness on the global market is the WTO multilateral trade regime, which should be in accordance with Western Balkans’ future EU trade obligations. The precondition for EU membership is membership in the WTO, which is not important just because of the international trade regime that WTO sets and oversees but because of the sets of technical agreements that lay down basic trade principles. Institutions like WTO have another function that has been largely ignored by researchers—reduced volatility in trade policy and trade flows. Exposure to global markets increases terms-of-trade volatility, and governments seek to insulate their economies from such instability through membership in international trade institutions and even regional trade integrations (Mansfield and Reinhardt 2008). But in WTO accession negotiations, Western Balkan economies can be asked to commit to greater trade liberalisation than the EU trade regime envisages. An example of this was Estonia’s accession to the WTO, which resulted in new trade concessions that EU had to give in the WTO framework when Estonia joined EU. Aligning the two processes of EU and WTO accession is of paramount importance in building competitiveness of the Western Balkan economies; the role of policy makers is vital to that end.

The process of WTO and EU accession should be compatible for Western Balkan countries. Western Balkan companies should be able to envisage future trade regimes enforced by these economies so they can position themselves better on a single European and global market. So, the question is not, what are the comparative advantages for Western Balkans economies in international trade under a free trade regime? But rather, what are the competitive advantages for Western Balkans economies on the single European market at the moment they join this integration? The trade regime applied by the Western Balkans will determine their competitiveness. When Serbia joins the EU, it will not be important whether it is globally competitive in fruit production but rather if it is competitive compared to other EU members.

Policy makers in the region must be able to create a stable and predictable framework for the locally operating companies. At present, various trade regimes influence the competitiveness of the Western Balkan economies and companies operating in these economies—CEFTA 2006 trade regime, EU preferences trade regime, WTO multilateral trade regime and many others that regulate trade with other countries in the world on a more preferential basis than MFN and WTO trade regimes. Companies must be able to predict the applicable trade regimes, and there must be some stability and time horizon of application of certain regimes (Bjelić 2013). The dominant trade regime for the Western Balkan economies as they approach EU membership will be the EU common trade regime. But even this could soon change with the multilateral trade negotiations round in the WTO—the Doha trade round—which can significantly liberalise the trade regimes of WTO members including the EU, especially for trade in agricultural products.

Trade policy makers in the Western Balkans must explore the ability of these economies to take an active role in the Common EU Trade Policy so they can create a stable framework of operations for the companies operating in this region. This means that rules of doing business must be the same for all companies—big or small, foreign or domestic. Apart from this, many institutional mechanisms must be in place to ensure the fair and legal operation of companies that go under functional market economy condition for EU membership. Then the competitiveness of the Western Balkan economies will depend on the competitiveness of the companies that operate there, leaving aside the strategic trade policy of global trade powers.

The Western Balkans trade policy will be shaped significantly by the EU common trade regime towards non-member countries, but this trade reform in the Western Balkans will not only include the application of a new tariff schedule and regulations connected to the application of nontariff measures, but will be more focused on the development of trade infrastructure and institutions that can take all EU membership obligations and apply them in practice.

5 Conclusions

The Western Balkans is a region diverse in ethnic and cultural heritage but similar in economic structure, trade interests and the taste of local consumers. The formal trade policy–creation process in this region is often ambiguous, non-transparent and contradictory since there is no focus organ for trade policy coordination, and usually the trade regime changes significantly over short periods of time. The trade regime of the Western Balkan countries is fairly liberal, but it is far from the tariff levels of the EU. Trade policy creation is now significantly influenced by international organisations like EU and WTO, to which these economies belong or seek membership.

Apart from the formal actors who shape trade policy, this process is largely influenced by informal actors such as large domestic and foreign companies. Every group has its own specific interest and lobby and pushes for a specific trade policy outcome, which will result in profit maximisation. Informal actors use bribes and layoffs of large number of employees as the main instruments of influence. Their final aim is protection in the local market from foreign competitors with higher tariff rates or application of nontariff barriers. Transnational corporations are very important in international trade today and can wield significant influence on trade policy creation in the home country as well as in host countries of their foreign affiliates.

Globally, the countries of the Western Balkans are at lower levels of trade competitiveness. One of the causes for this low level of competitiveness is the performance of weak and underdeveloped state institutions, which is often exacerbated by endemic corruption. The Western Balkan economies have underdeveloped state institutions and are not fully functioning market economies; thus corrupt practices and monopolistic behaviour of companies is widespread. The state in this region must be able to set a fair and sustainable market system and to empower the state institutions to function properly. This will minimise the influence of informal actors on trade policy creation in this region. All this is a precondition for joining the EU, and some positive benefits from EU membership for Western Balkans lie in this area.

The Western Balkans are faced with three trade regimes—trade regimes for CEFTA 2006 members, the EU common trade regime and the multilateral WTO trade regimes. Trade creators must be clear which trade regime will prevail in the future to provide a stable framework for company operations. Free trade today is still an unreachable goal, and the question of a nation’s competitiveness is discussed not in the global context but rather in the framework of specific trade regimes. The competitiveness of Western Balkan economies will depend on their ability to specialise and sell on the single EU market shielded from outside competition by the EU common trade regime. But the changes in this regime can also be foreseen in the ongoing round of multilateral trade negotiations in the WTO.

Notes

- 1.

As defined in European Union policy documents.

- 2.

Separate customs territory, as defined under UNSCR 1244.

- 3.

It represents simple average tariff rate.

- 4.

Not in the form that is calculated from a percentage of the value of the good that is traded but rather in some specific form.

- 5.

Zakon o spoljnotrgovinskom poslovanju, Službeni glasnik RS br. 36/2009.

- 6.

Zakon o genetićki modifikovanim organizmima, Službeni glasnik RS br. 41/2009.

- 7.

According to Novi Standard Magazine, Internet, http://www.standard.rs/ivan-ninic-kako-je-dinkic-pokusao-da-ucini-amerikancima-da-se-legalizuju-mutanti-gmo.html

- 8.

Bart Staes, Written Question E-4037/00 to the Council (2001/C 261 E/021), January 3, 2001, EN Official Journal of the European Communities C 261, September 18, 2001.

References

Baldwin, R. E. (1989). The political economy of trade policy. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3(4), 119–135.

Beyers, J., & Kerremans, B. (2004). Bureaucrats, politicians, and societal interests: How is European policy making politicized? Comparative Political Studies, 37(10), 1119–1150.

Bjelić, P. (2003). Ekonomika međunarodnih odnosa. Belgrade: Prometej.

Bjelić, P. (2013). World trade organization and the global risks. In A. Alemanno, F. den Butter, A. Nijsen, & J. Torriti (Eds.), Better business regulation in a risk society (pp. 193–206). New York: Springer.

Bjelić, P., & Dragutinović Mitrović, R. (2012). The effects of competing trade regimes on bilateral trade flows: Case of Serbia. Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics – Journal of Economics and Business, 30(2), 267−294.

Bjelić, P., & Jaćimović, D. (2012). Impact of the world economic crisis on trade and foreign investments in the West Balkans. In: B. Boričić & M. Jovičić (Eds.), Factor markets and the effects of the world crisis (Conference proceedings of selected papers, Vol. 2. pp. 45–62). Belgrade: Faculty of Economics Publishing House (CIDEF).

Bjelić, P., Šećeragić, B., Čeku, H., Petronijević, V., Jelačić, M., & Vinca, D. (2012). Freedom of movement of people and goods between Kosovo and Serbia in the context of regional co-operation: Scientific research study. Novi Sad: Centar za regionalizam.

Brada, J. C. (1991). The political economy of communist foreign trade institutions and policies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 15, 21l–38l.

Cooper, R. N. (1973). Trade policy is foreign policy. Foreign Policy, 9(Winter), 18–36.

Crosby, B. L. (1996). Policy implementation: The organizational challenge. World Development, 24(9), 1403–1415.

Drabek, Z., & Bacchetta, M. (2004). Tracing the effects of WTO accession on policy-making in sovereign states: Preliminary lessons from the recent experience of transition countries. World Economy, 27(7), 1083–1125.

Dragutinović-Mitrović, R., & Bjelić, P. (2013). International competitiveness and asymmetry in trade regime in the EU integration: Evidence from Western Balkans’. In The tenth international conference: Challenges of Europe: The quest for new competitiveness proceedings, 2013, Faculty of Economics, Split.

Finger, J. M. (1984). The political economy of trade policy. Cato Journal, 3(Winter), 743–755.

Kaminski, B., & de la Rocha, M. (2003). Stabilization and association process in the Balkans: Integration options and their assessment (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3108). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Kathuria, S. (Ed.). (2008). Western Balkan integration and the EU: An agenda for trade and growth. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Krugman, P. R., & Obsfeld, M. (2003). International economics: Theory and policy (6th ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley.

Mansfield, E. D., & Reinhardt, E. (2008). International institutions and the volatility of international trade. International Organization, 62, 621–652. doi:10.1017/S0020818308080223.

Milner, H. V. (1999). The political economy of international trade. Review of Political Science, 2, 91–114.

Perez, M. F., Brada, J. C., & Drabek, Z. (2012). Illicit money flows as motives for FDI. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(1), 108–126.

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: Free Press.

Rodrik, D. (1995). Political economy of trade policy. In: G. M. Grossman & K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (Vol. 31, pp.457–494). Elsevier.

Stopford, J. M., & Strange, S. (1991). Rival states, rival firms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Woolcock, S. (2010). The treaty of Lisbon and the European Union as an actor in international trade (European Centre for International Policy Economy (ECIPE) Working Paper, No. 01/2010). Brussels: ECIPE.

World Trade Organization (WTO), International Trade Centre (ITC), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2013). World tariff profiles 2013. Geneva.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media Netherlands

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bjelić, P. (2015). Building Competitiveness and Increasing Trade Potential in the Western Balkans: Policy Making in Preparing for European Integration. In: Thomas, M., Bojicic-Dzelilovic, V. (eds) Public Policy Making in the Western Balkans. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9346-9_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9346-9_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-9345-2

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-9346-9

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)