Abstract

This chapter explores how significant is the non-material dimension of work to self-reported life satisfaction (or “well-being”). It attempts to do so with empirical rigour and, as such, is one of few attempts to approach life satisfaction relative to the labour market in a quantitative way. The paper begins with a European database, and then expands its analysis over a global data sample. The distinction is important, as, for example, an independent variable such as “unemployment” has meaning in a European sample, but considerably less meaning in poor, developing countries, where other measures of labour market outcomes are required. Among the paper’s findings is that income from work, on average, explains only about 50 % of self-reported life satisfaction relative to the labour market.

Our gratitude goes to Annette Schut and Zhen Zhang for their most competent research assistance. We also benefitted from the comments of Anna Biondi, Sameer Khatiwada, Christian Kroll, Per Ronnas and Werner Sengenberger on an earlier version of this paper.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The ILO introduced the concept of decent work in 1999. It was defined then as the “promotion of opportunities for women and men to obtain productive work in conditions of freedom, equity, security, and human dignity”. The concept places work at the fulcrum of economic opportunity and human rights, individual and social. The sentiment that economic and social development are, in fact, two facets of the same process and, by implication, neither is sustainable without the other, situates work in an other than purely economic or material dimension. In short, it is a concept that evokes an important, non-material dimension of economic activity, and of life.

The inherent value of decent work is easily intuited by all, and its support as a worthy aim requires no particular evidence. People do not need proof that decent work is preferable to indecent work. Support for that which is, therefore, self-evident has flourished since 1999. This is reflected in the broad political endorsement that the concept and objective have received at multi-lateral and national levels. Indeed, it has made its mark politically.

But, it is making its mark scientifically as well, in the social and natural sciences, through the burgeoning academic literature on the “economics of happiness”. The stream of research on happiness is a confluence: one centred on how the discipline of economics evaluates well-being, the other on how research in psychology does the same. Both are social sciences, both strongly grounded conceptually in a view of human behaviour, and both having the epistemological aim of understanding it. Both inquiries have their own set of assumptions to explain behaviour. Both explore it in a way that is largely contextual. But, as behaviour is more than contextual, so thus is happiness. It is also physiological and genetic. Medical research thus joins this confluence.

This chapter begins on the conceptual level and distinguishes between how economics and other sciences might approach the question of well-being. Methodological issues also arise in this discussion. The second section approaches the matter empirically. A non-comprehensive decent work index is constructed with the aim of excluding “income” as an explanatory variable, and this index is applied to the 27 countries of the European Union. Our well-being measure here is from the Eurobarometer. A simple econometric test evaluates the relation between this index and self-reported measures of well-being. The third section reintroduces income in an effort to determine just how important it is or is not. The data for this section are global, not just European, from the Gallup World Survey.

Part One: Standard Economic Explanations of Well-Being Are Found Wanting

Interest in the economics of happiness arose from the inadequacy of normal economic measures of well-being: GDP per capita, gross national income, while useful in their own right, are nonetheless awkward and imperfect measures of well-being. They are imperfect even in standard economic terms since, as aggregate national averages, they do not indicate the distribution of this well-being. In addition, and this is what is so closely aligned with ILO values, this research is an approach to well-being that rigorously accords non-material dimensions as vital components. Pride, identity, fairness, inclusion or belongingness – in life, but also at work – become measurable indicators of the well-being that should be associated with growth or development.

Through its focus on a fuller view of what constitutes well-being, it is a research agenda that has everything to do with the concept of decent work, and its findings are extraordinarily supportive of that concept. Worthwhile, then, it is to take a closer look at just what the economics of happiness is all about.

The interest in this topic is not particularly new, as, over time, a large amount of thinking in economics and organizational psychology has dwelt on how a happy and motivated worker is also a productive one: happiness does indeed show up on the bottom line! Many studies in this vein argue that “non-material” does not necessarily mean “non-economic”.Footnote 1 It is also the case, explored in medical research, that environmental influences on the experience of happiness do, of course, exist, but that individuals also have a variable genetic predisposition to happiness. Some people are simply genetically predisposed to be happier than others. Both of these paths of understanding are undoubtedly highly and intrinsically valuable, but “happiness and productivity”, or “happiness and genetics” are not really the point here. The point is that the non-material dimension of work appears to matter and if it does, should not policy address interest in this matter?

Origins of Inadequacy in Explaining Well-Being

In both the academic and policy communities, the traditional propensity in economics to define well-being in purely material terms is increasingly unsatisfying: yes, maybe people do want that bigger, more luxurious automobile, but they also want clean air and less congested roads. The thinking on viewing happiness in terms broader than material acquisition is not new in economics. Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, and others in the nineteenth century were quite mindful of this – as was Aristotle many centuries before.

What appears to have been lost, as the discipline of economics progressed, may owe less to some sort of ideological bend in the road, than to the “scientification” of economics: “as economics grew more rigorous and quantitative, more parsimonious definitions of welfare took hold. Utility was taken to depend only on income as mediated by individual choices or preferences within a rational individual’s monetary budget constraint” (Graham 2011, emphasis added). Economists no longer needed to think broadly about happiness or the “common good” – happiness could simply be inferred from the choices that people made – their “revealed preferences”. Happiness, well-being, life satisfaction became non-issues: if the individual has made a choice, then they must be happy about it, or, in the jargon of economics, find “utility” in it.

There is much wanting in this parsimony, the key doubts centering on the three highlighted words above – “choice,” “individual” and “rational”. Choices are circumscribed or, indeed, can be unavailing. The Nobel economist Amartya Sen argued compellingly that poverty is the absence of capabilities – capabilities, therefore, to choose. For the poor, “preferences” are not “revealed”. What is revealed is an absence of choice. If choice is proscribed, then the very notion of “individual utility maximization” is quite limited. Individual utility maximization when de-jargonized can be thought of simply as “what do I prefer, given what I can afford?” The absence of choice, in Sen’s critique of his discipline, nearly makes a mockery of “preference”. Not coincidentally, Sen was among the distinguished guest speakers at the 1999 International Labour Conference (ILC), where the concept of decent work was first introduced, and where Sen advanced an other than purely “economic” construct of work.

Utility Is Relative, Not Merely Individual

Perhaps more fundamentally limiting, however, especially in view of economics’ stature as a behavioural science, is that behavioural choices are not always about the individual, on the one hand, and exclude choices that individuals might like to make, but over which they have no control, on the other. Standard economics reposes on a view of “behaviour” that is narrow indeed, limited in its capacity to explain and, worse still, sometimes giving the wrong answers as to what people truly want.

A standard economic approach to behaviour cannot explain the comportment that people otherwise manifest, such as altruism, trust, compassion, the search for companionship, which are often not within the calculus of material gain or loss, or reliant upon a budget line. The Harvard biologist, Edmund O. Wilson, in a seminal work, Sociobiology (Wilson 2000), found a biological basis for the altruism of certain species – an altruism nonetheless consistent with Darwin, in the sense that altruism can preserve the chances of the survival of the species.

For those exploring the economics of happiness, the conclusion is stark: individual utility, call it preference, certainly matters, but many preferences are not only individual, but interdependent with the standing of others to whom we compare ourselves, or the “orbit of coercive comparison”. A well-known natural experiment found that people would prefer to earn US$50,000, if others to whom they compared themselves were earning US$25,000, but would not prefer to earn US$100,000, if the others were earning US$200,000. Similarly, it turns out that the adverse health consequences of unemployment are less great the more that people around you are unemployed (Wilson 2000, p. 9). “How am I doing?” This depends on how others are doing.Footnote 2

Another Nobel economist, George Akerlof (2007), and his colleagues have written extensively on “identity”. A key insight of their work is that “people have views regarding how they and others should or should not behave”, and these are guides to behaviour beyond a simple price mechanism or rationality. People “engage in activities because they care directly about their identity”.

There is no purely material logic to these findings. People are fundamentally social beings; their individual preferences are often not absolute, they are relative:

we are inherently social creatures and our sense of self-worth and happiness derives in part from comparing ourself with others. If others’ wealth or income is different than ours, then we are more or less satisfied with our own level by comparison, regardless of our absolute level (assuming a minimal amount to meet basic human needs). Consequently, if there are considerable differences in wealth and income in a society, then there are also likely to be higher levels of dissatisfaction. Wealth and income are typically concentrated in a small proportion of the community, leaving the majority of people dissatisfied by comparison (The Sustainable Scale Project 2003).

The protest against the “1 %” in the Occupy Wall Street movement owes its origin at least in part to this phenomenon.

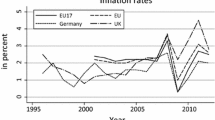

And, there are preferences that affect well-being, but over which people have no control. Much evidence suggests, for example, that unemployment in general – not our own this time, as in the example above – and inflation are matters that affect well-being, but which are beyond our control. Some notional evidence of this is shown in Fig. 15.1. In fact, it supports both points: others’ problems influence people’s own well-being; and there are some preferences, such as full employment, over which they are powerless, but which do matter.

Analyses of self-reported well-being have potential, if untested policy significance. Well known, of course, is the initiative undertaken by the Kingdom of Bhutan since 1972, to give pride of place to a measure of “gross national happiness”, rather than relying upon the retroactive measures of economic output upon which GDP is based. Less well known is its currency of interest among all countries:

The General Assembly of the United Nations has added Bhutan’s model of Gross National Happiness (GNH) on its agenda to see whether it can be used as a development indicator. In a non-binding resolution, the UN body called on member states to draw up their own measures of happiness based on Bhutan’s GNH principle. The goal is to measure economics not only in terms of production and per capita revenue but also in terms of people’s sense of satisfaction (AsiaNews.it 2011).

The inadequacy in meaning of purely economic numbers to express well-being is a sign, and a healthy one, of the times. The Government of France commissioned an enquiry in 2009, headed by the Nobel laureates, Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen, and the eminent French economist, Jean-Paul Fitoussi, “to identify the limits of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and social progress” (Stiglitz et al. 2009). And, for 20 years now, the UNDP, through its human development index, has measured countries’ development using a yardstick well beyond economic data alone (and, in so doing, defining “development” as something other than purely economic).

Well-Being and Decent Work

The “new science” (Layard 2005) of happiness is the result of the intersection of economics’ focus on “revealed preference” as an understanding of behaviour, and experimental psychology’s interest in “subjective” or “self-reported” perceptions of well-being. Often, reported happiness or well-being or life satisfaction, is used rather inter-changeably. There are some grounds for this, as they are related to each other, but they are not synonyms. Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the U.S. Federal Reserve System notes that: “researchers have distinguished between two related, but different, concepts – ‘happiness’ and ‘life satisfaction’. They use ‘happiness’ to mean a short-term state of mind that may depend on a person’s temperament, but also on external factors, such as whether it is a sunny or a rainy day. They use ‘life satisfaction’ to refer to a longer-term state of contentment and well-being” (Bernanke 2010). The semantics of the matter is not unimportant, but this report will use the term “well-being” and “life satisfaction” interchangeably, and draws conclusions on the growing scientific interest in the non-material dimensions of work.

That the concept of decent work has gained such widespread acceptance since 1999 is due in large measure to its simple, but compelling perception that work indeed does have both material and non-material – human, social – dimensions. In fact, the decency of work implies both such dimensions. As to the former, for example, pay, an economic variable, can be said to be “decent”, the implication being that the amount is adequate for an individual’s consumption needs. Yet, the decency of pay is, as noted above, also a relative measure that depends upon an orbit of comparison of those doing similar work. If the work is the same, but there is great disparity in pay among those doing it, then pay might be judged as less than decent; unfair, even if, objectively, the pay is more than enough to live on. While the adequacy of earnings is a quintessential economic indicator, it also has a non-material dimension relating to how fairness is considered and, in turn, affects well-being.

A third of a person’s life is spent at work. A fair proportion of well-being depends upon the non-material dimensions of that activity. Work, beyond income, conveys well-being, or it does not. This has been the singular insight of the concept of decent work: money matters, but it is not the only thing that matters in work. It is not merely the income-generating, demand-derivative pursuit that is the stuff of labour economics textbooks: it defines people, and does so for better or for worse. “Well-being”, understood as self-perception of satisfaction, does indeed have a strong economic component: across countries, it is positively related to income, as revealed by global surveys, such as those by the World Values Survey Organization as well as Gallup World Polls (Deaton 2008). This is no doubt part of the explanation of why a large majority of working men and women in over 100 countries deem work to be “very important” or “rather important”. The Gallup results are shown in the Fig. 15.2.

Clearly, however, the chief need here is to unbundle the adjective “important” into its material and non-material dimensions.

The Health of the Unemployed

Unemployment strains the social fabric in ways that the Arab Spring demonstrated. Beyond its impact on social stability, there is also an extensive literature relating unemployment to the rise of economic crime rates (Papps and Winkelmann 1998).

Arguably, the most critical non-material dimension of work is its effect on health, both psychological and physical. Much of the evidence of this comes from the rather extensive literature on the effect of unemployment on psychological well-being. National survey data from the United Kingdom, for example, show that: “unemployment appears to have a significant impact on the individual since it is associated with a rise in anxiety, an inability to face up to problems, a loss of confidence and a reduction in self-esteem, the ability to enjoy day-to-day activities and the level of general happiness” (Theodossiou 1998). One important and consensual theoretical conclusion to draw from these findings is that, contrary to neo-classical economic theory, unemployment is involuntary: as the unemployed experience significant disutility from their labour market status, it can be logically assumed that few would opt for it. Indeed, in the British study, considerably higher well-being is reported by those even in low-paid work: “Thus, in a sense, it appears that it is more important for human beings to have a job than just money” (Theodossiou 1998, p. 93). This is shown in Fig. 15.3.

Relative to a high-paid worker, an unemployed person is 250 % more likely to feel less happy, and 180 % more likely to lose confidence. Medical research on the unemployed invokes phenomena such as “loss of control” and “learned helplessness” (Baum et al. 1986). Perhaps surprisingly, however, the low-paid worker often reports a higher level of well-being than the high-paid worker along the dimensions represented in the figure.

The findings on the unemployed are not surprising and have, in fact, been intuited truths for centuries. The French philosopher, Diderot, observed that: “work is something to which man is condemned by need, but something to which he owes his health”, while Sigmund Freud identified work as one of the two chief sources of psychological health, the other being love (Warr 2007). Henry Ford believed “Work is our sanity.”

Unemployment could indeed affect the perceived well-being of those who are not unemployed. Figure 15.1 showed that, in countries with lower unemployment, more people, i.e. not only the unemployed, reported being “fairly satisfied” with their lives (EU’s Eurobarometer survey).Footnote 3

While there is broad consensus that the domains of psychological well-being are adversely affected by unemployment, that consensus also extends to physical health risks. One study comparing long-term unemployed men with a control group of employed workers found that:

Days in bed during the six months averaged five for the unemployed and .9 for the employed. Visits to the physician were five times more in the unemployed than employed men; the unemployed men averaged taking twice as many medications as the employed men; self-rated health was less favorable in those who lost their jobs. Although the number of diagnosed illnesses did not differ between the groups, the presenting complaints for the increased number of physician visits were most often related to gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin disorders (Linn et al. 1985).

And, while we do not “yet understand how the physical health and mental health of nations are connected” (Blanchflower and Oswald 2011), there is certainty at the individual level that psychological factors can have physical consequences, and vice versa. Unemployment-related stress, for example, can have adverse cardio-vascular consequences. A relationship between psychological and physical health among the unemployed was found in the aforementioned study:

Those who made more visits to their physicians had more symptoms of somatization, depression, and anxiety. More time spent in bed was associated with increased somatization and depression. Those who took more medications had more somatization and were less internal in their locus of control. Poorer self-assessed health correlated with several of the psychological states, such as more somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, depression, and anxiety and less life satisfaction (Linn et al. 1985, p. 504).

At the tragic extreme, many studies have found significantly higher suicide rates among the long-term unemployed (Dooley et al. 1996). More generally, studies also find that the unemployed, with no previous illness, tend to die younger than the employed (Doyle et al. 2005).

Well-Being, the Macroeconomy and Labour Market Structure

The significance of this rising interest in the non-material dimensions of well-being is its potential to tilt the balance of macroeconomic policy-thinking towards more explicit service of what makes lives more satisfying to live: a sort of “macroeconomics as if people mattered”. This is implicit in the UN General Assembly’s appreciation of Bhutan’s GNH. Evidence shows that as work becomes more decent in income terms, people’s concerns over corruption and interest in democratic governance increases (Banerjee and Duflo 2008). They are also more likely to invest in their children, an investment inter alia in future citizens. Employed wage-earners are almost twice as likely as the unemployed to report having a general trust in people. They also report a substantially higher propensity to have some type of civic engagement.

A major review of factors affecting happiness in the world yields a consistent finding: “Unemployment is about ten times worse for happiness than inflation” (Graham 2010). For governments wishing to pursue the well-being of their countries’ citizens, the implied macroeconomic policy message is rather clear: inflation is less of an enemy than is joblessness.Footnote 4

Labour market structure matters as well. If, in one study cited earlier, low pay seems considerably more exempt from the sort of psychological ill-being that characterizes the experience of the unemployed, the same cannot be said for job insecurity.

A broadly based empirical finding confirms that “there is a powerful link between job insecurity and low well-being”. Self-reported well-being is substantially higher among those who deem it as “not at all likely” that they will lose their job, and substantially lower among those who report “it would not be at all easy to find another job” (Blanchflower and Oswald 2011). Obviously, this finding does not apply to those voluntarily in temporary jobs.

A collection of other studies finds that:

Low job security is frequently associated with flexibility and this has significant adverse effects on self-reported psychological and physical health outcomes. Health deteriorates when people are anticipating job loss. A study of British civil servants showed those who experienced job insecurity reported a significant worsening of self-rated health compared with those who experienced continuing job security. Women who experienced reduced job security reported an increase in long standing illness. Women also showed a larger elevation in blood pressure associated with reduced job security, marking them at risk for cardiovascular disease (Blanchflower and Oswald 2011, p. 11).

Medical research findings thus tend, in a sense, to confirm what might be called the health advantages of decent work: “Having secure employment in favourable working conditions greatly reduces the risk of otherwise healthy people developing limiting illness. Secure employment increases the likelihood of their recovery. These findings have considerable implications for both health inequality and economic policies” (Bartley et al. 2004).

Inequality, Economic Growth and Well-Being

A certain consensus is emerging in studies on what actually constitutes well-being. Moreover, this consensus is generalized across countries. As noted, income and well-being are related, although with the previously discussed qualifications. Health and happiness appear to be even more strongly correlated, again, however, with the qualification that health and healthcare systems are, to a certain degree, income-dependent.

Other common findings are that marriage and religiosity tend to be positively related to well-being. Age, too, is found to be related to well-being, albeit in a U-shaped fashion: well-being appears to be at its ebb around the age of 40 (Powdthavee 2010). There are other findings, however, that have more implications related to the conceptual underpinnings of decent work.

Some of these have to do with macroeconomic outcomes, other than unemployment, that relate to happiness. A common finding, for example, is that inequality and well-being are directly related: the greater the degree of inequality, the lower the level of well-being (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009). Figure 15.5 provides visual support for this. Put another way, more equal societies show a higher degree of perceived well-being. This could be related to the finding that relative, rather than just absolute income appears to affect well-being.

Yet, it is not only direct income inequality that is negatively related to well-being: so, too, is inequality arising from indirectly income-related factors. For example, the UNDP’s gender inequality index comprises measures of maternal mortality, fertility rates, women’s seats in national parliaments, labour force participation rates, and various indicators of reproductive health. Figure 15.4 shows a relatively strong correlation between indices of well-being and the UNDP gender inequality index.

One rather surprising finding (shown in Fig. 15.5a, b) is that: “strong economic growth is bad for happiness” (Graham 2010; see also Deaton 2008). Called the “paradox of unhappy growth”, this result could be associated with the higher level of uncertainty that growth might generate, or the unequal distribution of income gains arising from growth. In addition: “dissatisfaction in rapidly growing countries is the result of the accelerated increase in expectations of material consumption, and competition for economic and social status” (Inter-American Development Bank 2011). Whatever the reason, this is additional evidence that growth and well-being neither move in tandem nor are synonyms. To sum up, at least from the point of view of perceived well-being, policies that either do not address inequality or focus inordinately on high growth alone, may be at the expense of well-being.

The paradox of unhappy growth (a) GDP growth and job satisfaction. (b) GDP growth and life satisfaction (Source: Inter-American Development Bank 2011)

In international reviews (and without further elaboration here), the following characteristics appear to apply to national senses of well-being (Blanchflower and Oswald 2011, pp. 20–21).

-

Low inequality.

-

High “social capital” and strong friendship networks: for example, in addition to the “misery loves company” phenomenon of less loss of well-being among the unemployed if they are surrounded by others in the same labour market status, well-being among the unemployed – irrespective of the unemployment rate – declines less the more the unemployed person is surrounded by a network of support.

-

Low unemployment and inflation.

-

High levels of democracy and democratic participation.

-

High trust.

-

Strong welfare states and public spending: this may be a proxy measure for, for example, greater spending on education and healthcare, or lower inequality through taxes and transfer payments.

-

Low pollution.

It is hard to mistake the consonance of these findings with the “freedom, equity, security, and dignity” that describe the non-material components of decent work.

Key Determinants of Well-Being at the Workplace Itself

In any language, the question, “what do you do?” is elliptical. Obviously, what is being asked is what work do you do? Similarly (although increasingly an anachronism), women might be asked, “do you work?”, the implication being whether she worked for pay, rather than the often demanding and economically discounted work that constitutes child-rearing or running a household. The semantic point is that people quite often identify themselves by their work.

This chapter is not primarily interested in the micro-economic level of well-being. In passing, then, a survey by the French statistical agency, The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), finds that: “40 % of those questioned and 54 % of the labour force consider work to be one of the three elements that ‘best defines them’, it comes in second place far behind family”.Footnote 5 As Karl Marx put it in 1844: “Dans ma production, je réaliserais mon individualité, ma particularité; j’éprouverais, en travaillant, la jouissance d’une manifestation individuelle de ma vie, et dans la contemplation de l’objet, j’aurais la joie individuelle de reconnaître ma personnalité comme une puissance réelle, concrètement saisissable et échappant à tout doute” (Marx 1844).Footnote 6 Pride, self-affirmation, and self-esteem are causes of work satisfaction, but they are also the consequences of work performed in a favourable context.

One medical viewpoint notes that: “Work is perceived, therefore, as not only providing an income, but giving social legitimacy to our lives. For many, it may be the principal source of personal identity, mediating the sense of being a valued person necessary for self-esteem. A profession or trade gives us an identity – as a doctor, a teacher, an engineer, a motor mechanic, a secretary, an electrician, and so on.” Work similarly gives a sense of belonging, both in the social relations it brings, but also in the sense of the contribution to society that working for an organization can engender (Fryers 2006).

In the workplace, factors that affect well-being include: “opportunity for personal control, opportunity for skill use, job demands, variety, environmental clarity, income level, physical security, supportive supervision, opportunity for interpersonal contact, and valued social position” (Warr 2001).

These non-material factors appear to be vital to well-being, but they do not always prevail. Succinctly put from a micro-economic perspective, although from a far more comprehensive literature review, the evidence suggestsFootnote 7:

-

great decision-making power reduces rates of absence and turnover;

-

decision-making power increases level of performance and job satisfaction and reduces financial losses;

-

lack of decision-making latitude and recognition increases the risk of cardio-vascular diseases;

-

a clearly defined role decreases absenteeism and lateness;

-

low workplace support increases the rate of absence;

-

high support at work decreases the intention to quit jobs;

-

abusive supervision is associated with an increase in absenteeism;

-

high presence of interpersonal conflicts within a work team is associated with a reduction in performance;

-

the manager-subordinate relationship is the most commonly reported cause of stress;

-

managerial behaviour can have a significant impact on health outcomes of subordinates.

Part Two: Life Satisfaction and Decent Work: Can the Link Be Quantified?

In the foregoing sections, the strong conceptual link between self-reported measurements of well-being and the core tenets of the concept of decent work was presented, as were some empirical results. Both uniformly show the high consistency of findings from the economics of happiness research and the concept of decent work.

The present section delves more deeply into this link through some simple quantification between measurements of “life satisfaction” and some rather “reduced-form” variables intended to capture proxy measures of decent work across its four pillars. For reasons of their availability (and comparability), the data are drawn from the 27 EU member States.

Beginning first with a rather material dimension of work – income – the literature is quite consistent in finding that, indeed, money does buy happiness (Easterlin 1974). Thus, as distinct from the intra-national conclusions of the Easterlin paradox, in which increases in real income do not appear to show up in self-reported well-being, cross-country comparisons of incomes and well-being show a strong positive relationship. This is reflected in the simple correlation results in Fig. 15.6 for 20 EU countries.

For a larger sample of countries, income-related well-being is also in evidence. A qualification can nonetheless be made, as discussed below.

A Standard Deviation That Is Not So Standard

There is, then, compelling evidence from many sources that self-reported life satisfaction and income are positive correlates. Figure 15.7 shows the same for a sample of over 100 countries with a Pearson coefficient of r = 0.67.

There are, however, at least four comments to make on this profile. The first, as previously mentioned, is that money does matter when satisfaction with life is evaluated. Wealthier countries do report being more satisfied with life.

The second refers to the inadequate proxy of an aggregate measure of income as an explanatory variable. In essence, “money in the pocket” might matter, but GNI per capita is also highly associated with wealth-related provisions that a State might be able to provide. So, is it only the money in the pocket that makes people satisfied, or the fact that healthcare and education systems are superior, the streets cleaner, civil rights more guaranteed and the rule of law more dependable, available and predictable? All these are ancillary dividends of income quite beyond personal bank accounts.

The third comment refers to what hides behind any aggregate number, and it is also income-related. GNI per capita says nothing of the distribution of that income. Indeed, an outlier removed from the country sample above, Qatar, has a GNI per capita of well over US$100,000 in 2005 PPP terms. However, this says very little about its distribution among Qataris and cannot usefully explain how people evaluate the satisfaction of their lives. Anticipating a major conclusion of this paper, it will be found that it is not just income that matters, but its distribution.

Fourth and finally, the data points presented in the figure above are not all that orderly. This is seen in Fig. 15.8, when a US$20,000 cap is placed on the sample: for example, life satisfaction in otherwise poor countries shows a high degree of deviation. Income, again, is not everything.

While the same positive correlation between satisfaction and income is evident, that relation is far less linear. Two explanations are plausible. First, and as mentioned, GNI per capita says nothing of its distribution. Second, and not adequately captured in a purely economic explanation, satisfaction is simply not just a function of income. This seems intuitive. Beyond the fulfilment of basic needs, it is hoped that this would be the case.

Beyond Income: Four Proxy Measures of the Non-material Dimensions of Decent Work

This section, however, is concerned with the non-material dimensions of decent work. Indications of these are represented by proxy measures across the four substantive components of the concept. These measures are:

-

The UNDP gender inequality index is a composite index including mortality and fertility data, the number of seats in parliament held by women, an educational attainment variable, the labour force participation rate of women and various indicators of reproductive health. Figure 15.4 showed a strong correlation between this index and the index of life satisfaction. Discussion returns to this variable below.

-

The Gini index,Footnote 8 as a measure of relative income inequality and, by extension, equity (and security) in labour markets, as the inequality measure is also an implicit reflection of how tax and transfer payments serve to offer some social protection against market-determined risks.

-

The unemployment rate, as an indicator of labour market slackness, is used as a proxy measure of the state of productive employment.

-

The variations in the extent of collective bargaining coverage are used to show the institutional embeddedness of social dialogue in economies in interaction with distributive policies to extend the fruits of bargaining results.

These variables were chosen to approximate the ILO’s four strategic objectives: productive employment (whence the unemployment variable); equality of opportunity (whence the gender inequality index); social protection (and thus the Gini index as a reflection of tax and transfers after market-determined incomes); and social dialogue, (our collective bargaining coverage variable).

In every instance, the dependent variable is life satisfaction as revealed by the Eurobarometer surveys. The independent variables are intended, respectively, as proxies for the four strategic objectives of decent work.

A Few Tentative Observations

The correlation matrix shown in Table 15.1 shows the degree of relatedness among the variables. The difficulty of adducing causation from correlation has been previously described in this report. For example, does unemployment make people unhappy, or are unhappy people more likely to become unemployed? While authors have addressed these issues through, for instance, using time-series panel data to evaluate the effect of a change in status on well-being, the issue of causality nonetheless remains an extant one in the present section. (It can, however, be noted here that the causal relation between unemployment and unhappiness does appear to proceed from the former to the latter.)

In order to draw the bold conclusions implied in this correlation, admittedly, much more to go on is needed. That said, some of the correlations presented in the matrix find broad support in the literature. In particular, the relatively strong negative relationship between unemployment and reported life satisfaction, shown above (and previously in Fig. 15.1) is corroborated by many others, including those to whose work was referred in the preceding section. Similarly, the strongly negative relation between the extent of inequality and reported life satisfaction finds a good deal of support in the literature, and is consistent with the hypothesis that utility is relative, rather than just absolute.

Three other observations are, at the very least, worthy of mention, if not resolution, at this juncture. The strong positive relation shown above between inequality and unemployment appears to be less prominent in existing literature. Again, this is not readily explained by a simple quantitative test: does the relationship, for example, derive from the fact that the more equal societies in this European sample are also the smaller, more homogeneous ones? The former trait, smallness, might allow greater ease of labour market absorption. The latter trait, homogeneity, begs the question that: if societies are more unequal, is this because their ethnic mix, or mix between migrant and domestic labour, is more heterogeneous, and more to the detriment of some ethnicities than others? The question is merely posed, rather than answered by this chapter.

Why collective bargaining coverage emerges as so weakly related to inequality is also a puzzle, the origins of which might be merely statistical. (The sample does not have many observations to go on.) Other explorations have found a relatively strong relationship between collective bargaining coverage and inequality (Hayter 2002). At present, these questions remain unanswered. It would seem promising, however, that a simple regression experiment could add further insight into, at least, the significance of inequality on reported life satisfaction, and on unemployment. These are visualized in Fig. 15.9a, b.

To obtain an early sense, prior to a modelling exercise, of whether these measures of decent work do bear a relationship to reported life satisfaction, a rank-on-rank correlation was made. Countries were first ranked on the basis of their reported life satisfaction. The four decent work measures were then ranked across countries in Eq. (15.1):

Where dw is the decent-work index for country n, g is the Gini index, gi is the gender inequality index, c is the extent of collective bargaining coverage, and u is the unemployment rate. Thus, a “country score” or rank was then calculated by aggregating all four ranks for an individual country and dividing by four. Consequently, the four measures comprising the index are equally weighted, there being no obvious rationale for weighting one more highly than another. The results are shown in Fig. 15.10.Footnote 9

The first observation is that there does appear be a clear correlation between the ranked measure of decent work and reported life satisfaction in a country. Moreover, with r greater than 0.5, the correlation is slightly higher than any of the pair-wise correlations in the matrix.

Two outliers appear of interest and invite some speculation. The first is that the United Kingdom appears to report a much higher level of life satisfaction than would be “predicted” by the decent-work measures. Although not presented here, this is a feature shared by other Anglo-Saxon countries and might even suggest that the very correlation shown above is a spurious one. Further analysis does not confirm this conclusion, however, and discussion will return to this in the conclusion.

The second outlier reported in the figure is the converse of the British case: while Romania reports the lowest life satisfaction in the sample, it scores considerably higher in the decent-work measures. Two observations might be made here. The first, Romania joins a group of countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) where reported life satisfaction is far lower than income alone might predict (Deaton 2008). Thus, while the inter-country relationship between life satisfaction and the level of GDP per capita presents in almost a linear fashion, the CEE countries tend to cluster together as outliers, well below where they “ought” to be in measured satisfaction. Authors have attributed this inter alia to the continued travails of economic and political transition in those countries – greater uncertainty, rising inequality, the fact that not everyone’s standard of living was improved by the transition – resulting in the empirical finding that many lives appear, in fact, to be worse off than they were in the previous political economy regime.

The second observation is that, while inequality might be rising in Romania and elsewhere in the region, it remains a region of relative income equality, the consequence of its political economy under communism. Unemployment, at 7.3 %, is not astonishingly high in Romania: in fact, it remains a country with well over 1.2 million subsistence farmers, which might have absorbed job losses in the Great Recession, thus yielding a (relatively) “low” unemployment rate more akin to that of a developing country. Finally, while trade unionism weakened substantially in the early transition years in the region, as the unions acquired new functions, the collective bargaining coverage rate in Romania remains at 73 % (and thus ranked highly in decent-work measures above), while it is, for example, only 35 % in Hungary.

Taking a Closer Look at the European Data

Adding a bit more rigour yields results that are consistent with the exploration thus far undertaken. The analysis now leads to the construction of an ordinary least squares multiple regression model built on two assumptions. The first is that the proxy measures of decent work discussed earlier are likely to be appropriate predictors of the level of life satisfaction. The second is that the relationship can logically be assumed to be linear i.e. the more decent is work, the more satisfied people are. This can be expressed in the following manner in Eq. (15.2):

where the dependent variable  is life satisfaction, β is the intercept,

is life satisfaction, β is the intercept,  is the Gini index,

is the Gini index,  the extent of collective bargaining coverage,

the extent of collective bargaining coverage,  is the gender inequality measure,

is the gender inequality measure,  is the unemployment rate, and

is the unemployment rate, and  is an error term. The regression results are presented on the following page.

is an error term. The regression results are presented on the following page.

An initial problem to resolve was hinted at in Fig. 15.7 above, showing a rather strong correlation between income and life satisfaction among countries. A legitimate question is the extent to which the four independent variables, intended as proxies for non-material dimensions of work, are, in fact, “hidden proxies” for the level of income? Three variables would seem exempt from the suspicion that income drives results. These are the income inequality measure, the unemployment rate and the level of collective bargaining coverage. As to the last, an argument could be made that collective bargaining coverage is indeed income-dependent and substantially lower in poor countries with large informal economies. This is arguably true, but does not apply to the sample of countries selected here: relatively wealthy countries of Western Europe and formerly Communist countries of the CEE.

One variable nevertheless remains suspicious, and that is the gender inequality variable. As described earlier, it is the UNDP’s composite measure incorporating vectors such as mortality rates and reproductive health. These are quite likely to be income-related. In consequence, the construction of the gender inequality variable for this paper’s model chose only: (i) the share of women in parliament; and (ii) the labour force participation rate of women. The hypothesis is that neither of these measures is plausibly income-related. This is an arguable point, indeed, and we relax this assumption later in the chapter.

The effort, therefore, has been to identify variables, which are as distant from income dependency as possible, to the extent that, what is being analysed here is truly the non-material dimensions of work.

Some First Conclusions on Europe

A few noteworthy conclusions can be drawn. First, and fundamentally, the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between life satisfaction and these measures of decent work can be rejected. In this model, satisfaction and decent work are indeed related, as summarized in Table 15.2. To over-summarize, in a sentence, it is preferred to be more rather than less equal over a range of dimensions.

The two variables that emerge as the most significant predictors of life satisfaction are the income inequality variable, and that of non-income dependent gender inequality variability. The two other variables, collective bargaining coverage and unemployment, turn out to be not significant, with the former even having the “wrong” sign. These are possibly casualties of model misspecification, as well as peculiarities of the chosen sample. Indeed, bivariate regressions using these variables, respectively, return results that are both of the right sign and significant. Figure 15.11 offers some visual support of this.

Of course, the selected measures of decent work do not explain all of satisfaction in life, and this could be the consequence of many factors. “Omitted variables” frequently diminish explanatory power, most notably income. It may also be true that the variables chosen are not the best ones for capturing decent work (as the ILO’s own, much broader identification of decent work indicators, clearly suggests).

On the purely speculative plane, however, the imperfect fit of this model is not necessarily an undesirable outcome. Perhaps the model’s conclusions are, in fact, suggesting that: “work is important, but it is not ‘all important’; there are other dimensions of life outside the workplace which make mine a satisfying life.” Consider, for example, Fig. 15.7’s strong correlation between life satisfaction and the UNDP’s Human Development Index. The latter is a composite of life expectancy, years of education and income. The correlation in Fig. 15.11 excludes the income variable.Footnote 10 In no way, of course, can the merely relative importance of work be unimpeachably inferred by the model’s results. Neither, however, are the results inconsistent with such a conclusion.

The multivariate model yields a higher explanatory outcome than bivariate regressions based on the individual independent variables. Doubts about the explanatory power of the variable on collective bargaining coverage are perhaps not too surprising, as it is not logically straightforward why its extent would matter to life satisfaction, unless it is related to decent-work variables that may matter more, such as relative income equality, a lower gender-based wage gap, or some other consequence of it on outcomes not measured by the model.

It will be recalled that the collective bargaining coverage variable was selected as a proxy measure of the extent of social dialogue or participation. In fact, this variable is not really designed to service this aim, as it is legal extension, rather than dialogue, that is often the main means through which collective bargaining coverage arises. This is dramatically so in France where, for example, trade union membership is in single digits, while the coverage of collective bargaining agreements extends to the vast majority of workers. Thus, it is perhaps the case that this variable is not a particularly good indicator of the true extent of participation.

The weak results of the unemployment variable are perhaps more surprising in view of the rather extensive (and consensual) literature on the relationship between unemployment and well-being. Many factors could account for this, such as sample composition. For example, an unemployment rate in one of the transition countries might not be a good indication of underemployment and the latter’s effect on well-being. It is not inconceivable, however, that there could be something akin to a hysteresis effect in play here; that is, a country with sustained high unemployment simply “gets used to it”. Such an explanation, moreover, would find support in the economics of happiness literature: lottery winners experience a momentary rocketing increase in well-being, and then return to their prior steady state; those who become physically disabled see their well-being plummet before returning to its prior level. This paper’s results, of course, prove none of this, but are not inconsistent with similar findings elsewhere.

Part Three: Taking Things Further: World Data, More Variables – And Including Income This Time

We now turn our attention to a vaster set of countries than the EU countries considered in the foregoing sections. The dependent variable still remains self-reported well-being, but now from a global data set – the Gallup World Survey on well-being. In the previous sections, it seemed arguable to eliminate “income” as an independent variable on the perhaps heroic assumption that income variance across a number of EU countries might be less important – because of relative homogeneity – in explaining well-being. The effort, then, was the search for plausibly “non-material” independent variables. In the present section, we also want to know just how much income matters.

There are two efforts in this section: first, as noted, it is time to bring income back into the picture to see just how much it matters. But we also expand our pool of plausible independent variables explaining well-being from the labour-market perspective. We do this in an effort to capture a broader view of labour market conditions in the world. For example, “unemployment” has a sturdy meaning in advanced countries – it means far less in poorer countries without social protection and where, therefore, the option to be unemployed exists far less.

We retain unemployment, nonetheless, but add data on, poverty, inequality, gender equality, amongst other variables, shown in Table 15.5. Most of them are significant under the chosen specification. We also construct aggregate indices. The indices allow an analysis of the evolution of decent work and its cross-country differences. A look at evolution is possible because the empirical work in this section uses panel data. The sample ranges from 2006 to 2010. We find that the evolution of the decent work indices is positive until 2008–2009, when, with the Great Recession, they decline or stagnate. The ranking of countries according to decent work correlates with income. Nonetheless, important variations in a country’s decent work cannot be explained only by its income. How do we know this? A small, technical digression explains.

The Importance of “Weak Exogeneity”

The most important assumption of the classical model for causal analysis is weak exogeneity; that is that the regressors and the disturbance term be uncorrelated.

This condition is expressed in Eq. (15.4). If there were an unobserved factor included in the perturbation term, and it was correlated with some “regressor” or independent variable, we would not be able to distinguish between the effect of the unobserved factor and the regressor. In such circumstances, causal analysis could not really be performed, since the correlation with the unobserved factor will overestimate or underestimate the effect of the variable of interest (3). In short, “weak exogeneity” is important: if only three things explain something, and we have data on both the something and the three things, then we can be more causally convinced; on the other hand, if ten things explain that something, but we only have data on three of those things, then any causal statement we might venture would be dubious.

The problem with the present inquiry is, as will be recalled, that the variables used as decent work indicators are likely to be correlated with income. Let us reconsider our measure of gender equality, the proportion of parliamentary seats held by women. In Fig. 15.4 we observe a clear positive correlation between the Gallup life satisfaction index and the gender equality variable. However, as seen in Fig. 15.12, it cannot be certain that this correlation is due to the variable itself or due to the positive correlation with income as well.

Gender equality and life satisfaction, with and without income. (a) Life satisfaction vs. Gender equality. (b) Standarized GNI vs. Gender equality. (c) Residuals of life satisfaction vs. Gender equality. The Gender equality indicator is the proportion of parliamentary seats held by women. The Life satisfaction indicator is the Life Today index from Gallup World Survey on well-being. GNI stands for gross national income measure described in the Appendix. The figures illustrate that the positive effect of the gender equality indicator on life satisfaction is positive even after controlling for income

As expressed in Eqs. (15.3) and (15.4), the adequate technical resolution of this problem is to consider a regression with the gender index but controlling for income. One immediate way to do so would be to first regress the life satisfaction index and income, and then regress the residuals of the first model with the gender equality index. The result is illustrated in Fig. 15.12a–c. They indicate that the gender equality variable has indeed a positive effect on life satisfaction in its own right, irrespective of income.

This is the purpose of multiple linear regression, if the factor in the disturbance term is observable we include it as an independent variable, thus controlling for its effect. This moves the discussion forward from the first sections of this chapter, where only the measures of gender equality and life satisfaction were regressed. When we add income to the picture, one observes a drop in the gender equality coefficient. This was predictable given that the income variable was missing. The important point is that, when adding the income variable, the relationship between life satisfaction and gender equality remains both positive and significant. To ensure that we capture the effects of the decent work indicator free of income, all the analysis is done in a multiple regression setting controlling for income.

The Variables and the Results

The aim of this section is to analyze whether the results obtained in the previous section hold using a larger sample and controlling for the effect of income.

Several empirical approaches were both considered and tried in the analysis of the problem of well-being.Footnote 11 The Panel Corrected Standard Errors (PSCE) approach produced the best results. PCSE allows controlling cross-sectional dependence, that is, the shocks that contemporaneously affect various cross-sectional units. This is the case for several specifications used in this analysis and in most cases has been dealt with.

The independent variable, the same for all specifications for better comparability, is, once again, the Life Today index from Gallup World Survey on well-being. The set of dependent variables includes plausible decent work indicators.Footnote 12 We use measures of gender equality, income inequality and variables plausibly related to decent work conditions.

In some cases several variables have been used to construct a synthetic variable called factor, the factor is a linear combination of the variables using specific weights.Footnote 13 Table 15.3 summarizes the variables and weights used to construct these factors. The interpretation of factors is straight-forward: together, they construct a combination of variables with different weights. Nor do the variables themselves require much logical justification as to why they might be favourable to or inimical to life satisfaction. There are some interesting discrepancies, however. Perhaps the most interesting case is the part-time employment factor. Female part-time employment displays a large, positive coefficient, while male part-time employment, while positive, is less great. And, finally, the proportion of part-time employment in total employment shows a large negative coefficient.

How could this be interpreted? Part-time employment represents work flexibility and, especially for women, could be related to maternity leaves or other non-market responsibilities. On the other hand, total part-time employment could reflect negative factors, such as underemployment or dual-job holding.

Which Labour Market Circumstances Are Most Important to Life Satisfaction?: Weighting the Variables

Table 15.4 reports the results of regressions of the various independent variables on life satisfaction. All the coefficients are unit independent because the regression was done with the standardized values of the variables.Footnote 14 Thus, they have the following interpretation: a change of one standard in the independent variable causes (ceteris paribus) an increment of the coefficient times the standard deviation in life satisfaction. The coefficients have in consequence the interpretation of relative importance – the higher the coefficient the higher (or lower, depending upon the coefficient’s sign) the relative weight to life satisfaction. It stands out that income is an important determinant of well-being, but it is not the only one. To illustrate this point consider the following. An increase of 13,000 dollars (one standard deviation) in income per capita increases life satisfaction by 0.7 points on a 10 scale. This is indeed a large effect, but decent work indicators have a sizeable impact as well. For instance, an increase in 7 percentage points (one standard deviation) in unemployment will decrease life satisfaction by 0.3 points. As can be observed in table 15.4, many decent work indicators have significant and sizeable effects on life satisfaction. Indicators related to gender equality increase life satisfaction, variables related to the harshness of work conditions and inequality tend to decrease it, finally measures related to unemployment or under employment have a negative impact on life satisfaction as well.

Since We Now Have the Relative Weights, Can an Index of “Decent Work” Relative to Life Satisfaction Be Constructed?

Having the estimates of the causal effect to life satisfaction of each decent work indicator, we might be interested in answering questions such as: how has the overall decent work indicator evolved in the sample, or how has the contribution of each variable been evolving over time? We would also be interested in knowing how each country compares in the level of decent work, and how distant this is from a ranking based solely on income. To answer all these questions we develop an index of decent work based on the relative importance to life satisfaction. The fundamental idea is just to add the contribution of each variable, computed as the variable times the coefficient.

Figure 15.13 shows the evolution of the decent work index, which shows consistent growth, and the income contribution to life satisfaction. A slowdown in the decent work index growth rate in the last year of the sample, 2010, might reflect the effects of the recent recession. To analyze the reasons for the improvement of the index as well as knowing in detail its structure it is convenient to consider the contribution terms of each decent work indicator. It is worth noticing however that the decent work contribution is of the same order of magnitude than the one of income, and in fact is much more variable.Footnote 15 Regarding the components of the index and its relative importance, in Fig. 15.14, the level contribution of each variable is shown as a percentage of the absolute value of the index. Self- employment (positive) and vulnerable employment (negative) stand out as the main contributors. The composition of economic sector makes a sizeable contribution as well, a higher share of services and a lower share of agriculture leads to an improvement in life satisfaction. An interesting result is that many variables have a larger impact than the unemployment rate which contributes only modestly. For instance child labour has a negative impact 3 times larger than that of unemployment. Regarding the evolution of the index Fig. 15.15 shows the evolution of each component of the index in value (not relative to the index). By analyzing the level it is easier to find the causes of the evolution of the index. There is a notable reduction of vulnerable employment, which is the main driver of the increase of the overall index. Child labour slightly decreases and thus has a positive impact on the index. Finally there is a decline in self employment, since the variable has a positive impact on life satisfaction, this dampens the improvement of the index. Nonetheless in the sample period, 2006–2010, there has been a significant improvement of the contribution to life satisfaction decent work indicators. In 2006 the indicators contributed minus 2.2 points to life satisfaction, whilst in 2010 the wedge had been reduced to minus 0.8.

Evolution of income and decent work contributions to life satisfaction (Source: Authors calculations based on the data set described in the Appendix)

Ranking Countries on Decent Work and Relative to Income

Can we rank countries according to the decent work indices and compare those to the ranking according to income? Fig. 15.16 presents the scatter of ranking GNI vs. our decent-work rankings. The correlation is far from perfect. But if we regress both rankings, GNI explains roughly 50 % of the decent work index variability. The message, as throughout this chapter, is that income explains a lot, but by no means everything.

Ranking of income and decent work (Source: Authors calculations based on the data set described in the Appendix)

The Result: The Relation Between Income and Life Satisfaction is Non-linear

There is one caveat in the discussion above: the assumption of a linear relation between Life Satisfaction and Income. Evidence suggests that the relation is better described as logarithmic. We perform a robustness exercise against log GNI specifications. We observe important losses of significance for several variables, nevertheless more than half of the decent work indicators remain significant, and of similar order of magnitude than that of income. Yet the logarithm of income explains some of the life satisfaction that was assigned to some decent work indicators. This is interesting as it implies – almost counter-intuitively, again, given the parabolic relationship between income and life satisfaction – that more income equates with more life satisfaction. But this is not unreasonable; as the model takes into account the non-linearity it can account properly that low levels of income will have a larger than average negative effect on life satisfaction. In the linear model this effect was ruled out by assumption thus some decent work indicators were found to explain the effect (as they are correlated with income and they can account for the “extra” effect of non linearity). This fact does not contradict the main argument of this chapter that decent work has an impact on life satisfaction of the same order of magnitude than that of income. The reason is the following, in low income countries it is true that income will be of more quantitative importance for life satisfaction, nevertheless in high income countries the quantitative effect of income will be smaller due to the same non-linearity.

Conclusion

This chapter had two modest ambitions. The first was to relate the findings of the growing literature on the “economics of happiness” to the main tenets of the concept of decent work. The complementarity between the two is close indeed. The second was to explore empirically the relationship between a measure of life satisfaction and proxy measures of decent work.

The chapter makes the argument that decent work and self-reported well-being are likely to be conceptually similar, and likely to be related in a causal way. There is, of course, more to life than work and the material, as well as non-material outcomes that work conveys. That said, the effort in this chapter has been to deal with the world of work, which engages most of our lives and has a preponderant effect on our well-being.

In the chapter’s first sections, a “first pass” at the question was the effort, using just European Union data, and to “firewall” any income-related dimensions of well-being from the analysis. This was because of the well-known (parabolic) correlation between income and well-being – i.e. if you are poor, an additional rupee means a lot more to you than if you are better off. Think, for example, of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1943).

As to the non-material dimensions of decent work, many of us might well argue that the results presented are hardly “non-obvious”: people presumably prefer decent to indecent work in broader terms than just pay; people presumably prefer to be satisfied than dissatisfied – whether at work or not. We would, of course, agree.

The final part of the chapter, however, expanded our indicators of “non-material” well-being, by re-introducing income as well. The purpose was to try to determine just how much income matters relative to other indicators of decent work. The answer, we find, appears to be about 50 % – hefty, but not the only variable in a happy life and, more to our point, a happy worklife – where happiness is also relative to those around you.

We feel our effort has been an analysis, not hitherto undertaken, of the close complementarity of the emerging literature on the economics of well-being and the concept of decent work – in our sense, at the macroeconomic level. We find robust empirical support for the proposition that the non-material dimensions of decent work are indeed related to how people evaluate their satisfaction with their lives as a whole.

By extension, this second point would seem quite consistent with those who argue that economic policy should not be unduly obsessed with “nominal” targets, such as the inflation or growth rate, important though these are, to the exclusion of “real” targets. If economic policy were to target “well-being”, then targeting poverty, inequality, status at work, and the other variables we considered would appear to matter.

Notes

- 1.

A recent exploration of this link is in, “The value of happiness: How employee well-being drives profits”, Harvard Business Review, January–February 2012. It is also why we use the term “non-material” in this chapter, rather than “non-economic”, as there is, of course, an “economics of happiness”.

- 2.

Satisfaction with income is influenced by social comparison, but it is also influenced relative to the individual’s previous income trajectory.

- 3.

Warr 2007, p. 41 for the Eurobarometer survey results. The survey asks: “on the whole, how satisfied are you, very satisfied (=4), fairly satisfied (=3), not very satisfied (=2), or not at all satisfied (=1) with the life you lead?”

- 4.

But policy implications from happiness economics findings are not always straightforward. For example, victims of crime suffer less psychological trauma, the greater the number of victims. Similarly, the psychological health of the unemployed is less damaged the greater the number of unemployed!

- 5.

- 6.

“Through what I produce, I realize my individuality, that which makes me special. I experience, while working, the pleasure of an individual facet of my life, and, in focusing on the object of my work, I have the personal pleasure of acknowledging my personality as a true force, concrete and unimpeachable.”

- 7.

- 8.

Initially, the male-female wage gap was selected as an (imperfect) indicator of gender-based discrimination in labour markets. The measure is imperfect because gender-based pay gaps have both observable and non-observable dimensions, and these cannot be disaggregated from the pay gap figures used. In other words, there are “objective” explanations for the existence of a pay gap, e.g. education, tenure, even economic structure, and there are “non-objective” or discriminatory explanations for the gap. Because wage gap data cannot fully reflect discrimination, regression results using this variable were not particularly strong. The variable was thus dropped and the UNDP gender inequality index was substituted.

- 9.

Of the EU 27, the comparison in this figure drops to 20, as a result of the absence of data on collective bargaining coverage in some of the countries. More crucially, the figure presents a “ranking” of countries on the basis of four criteria, argued to be proxy measures of decent work. It can, as such, in no way be considered a ranking of countries on the basis of “decent work”; there are simply too many component measures missing. There is, in consequence, little reason to name the countries in the ranking, as to do so would be misleading, if not outright erroneous.

- 10.

Admittedly, however, one encounters the same problem as with the gender inequality variable, e.g. years of schooling and life expectancy are highly likely to be income-dependent, and the figure above may merely be showing proxy measures of income.

- 11.

While the substantial amount of empirical work informing this paper has not been discussed, it is described in an annex.

- 12.

The sources used for the independent variables are: World Bank, ILO, Freedom House and Inter-Parliamentary Union. The sample ranges from 2006 to 2010 both included. The source of each variable is specified in Table 6 in the appendix. The number of countries in the sample varies from variable to variable, the number of countries for which the Life Today index is available is 191.

- 13.

See Tucker and MacCallum (1993) for further information in factors purpose and optimal weights.

- 14.

If the analysis was carried out in levels, the coefficients obtained would be not comparable, for instance the coefficient obtained for income would be smaller in absolute value that the one for unemployment. This cannot be taken as an indication that unemployment has a larger impact on well-being, rather it is just a consequence that income is on a scale of tens of thousands yet unemployment ranges from zero to one. A normalization is then required in order to interpret the coefficients quantitatively. One natural normalization is to standardize (subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation), then the coefficients can be compared. As an example consider a cross sectional regression between countries, a coefficient of 0.63 of standardized income would have the following meaning: Being above the mean in income by one standard deviation will imply (ceteris paribus) being above the mean in life satisfaction by 0.63 standard deviation.

- 15.

To a certain extent this probably reflects higher accuracy and availability of income data compared to decent work data.

- 16.

See Beck and Katz (1995).

References

Akerlof, G. (2007, April 25). Economics and identity. Stamp Lecture, London School of Economics and Political Science, p. 27, mimeo.

Andrews, D. W. K. (1991). Heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix estimation. Econometrica, 59, 817–858.

Angris, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An Empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

AsiaNews.it. (2011, July 22). ’Gross national happiness’ on UN Agenda. Retrieved January 19, 2012 from http://www.asianews.it/news-en/Gross-National-Happiness-on-UN-agenda-22177.html

Banerjee, A., & Duflo, E. (2008). What is middle class about the middle classes around the world? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 3–28.

Bartley, M., Sacker, A., & Clarke, P. (2004). Employment status, employment conditions, and limiting illness: Prospective evidence from the British household panel survey 1991–2001. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 501.

Baum, A., Fleming, R., & Reddy, D. M. (1986). Unemployment stress: Loss of control, reactance, and learned helplessness. Social Science & Medicine, 22, 509–516.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

Bernanke, B. (2010, May 8). The economics of happiness, speech at the University of South Carolina Commencement Ceremony, Columbia, South Carolina. www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20100508a.htm

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2011, January). International happiness (Working Paper No.16668, p. 17). Cambridge, MA: The National Bureau of Economic Research.

Brun, J.-P. (2008). Work-related stress: scientific evidence-base of risk factors, prevention and costs. http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/brunpres0307.pdf

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2, Spring), 53–72.

DeHoyos, R. E., & Sarafidis, V. (2006). Testing for cross-sectional dependence in panel data models. The Stata Journal, 6(4), 482–496.

Dooley, D., Fielding, J., & Levi, L. (1996). Health and unemployment. Annual Review of Public Health, 17, 449–465.

Doyle, C., Kavanagh, P., Metcalfe, O., & Lavin, T. (2005). Health impacts of employment: A review. Dublin: Institute of Public Health in Ireland.

Easterlin, R. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. David & M. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz. New York: Academic.

Fryers, T. (2006, May). Work, identity and health. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1501011/

Graham, C. (2010). Happiness around the world: The paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graham, C. (2011). The pursuit of happiness: An economy of well-being (p. 1). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Greene, W. H. (2011). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Hayter, S. (2002) Collective bargaining and income equality in an integrating world. http://ilo-mirror.library.cornell.edu/public/english/dialogue/actrav/publ/128/9.pdf

Hoechle, D. (2007). Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. The Stata Journal, 7(3), 281–312.

Inter-American Development Bank. (2011). Beyond facts: Understanding quality of life. Washington, DC: IDB Publications 79502, Inter-American Development Bank.

International Labour Office (ILO). (1999). Decent work. Report of the Director-General, International Labour conference, 87th Session, Geneva.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. New York: Penguin Press.

Linn, M. W., Sandifer, R., & Stein, S. (1985). Effects of unemployment on mental and physical health. American Journal of Public Health, 75(May), 504.

Marx, K. (1844). Économie et Philosophie, Notes de lecture, § 22, in OEuvres, Économie, tome II, p. 33, La Pléiade, Gallimard 1979.

Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

Papps, K., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Unemployment and crime: New answers to an old question (IZA Discussion Paper No. 25).