Abstract

In China as in many other countries, inequalities remain between women and men in areas as varied as access to health care, education, and employment, wages, political representation, representation of assets and, in private life, decision-making within the couple and the family and sharing of domestic tasks. The aim of this chapter is to draw up a socio-demographic inventory of the situation of Chinese women in the early twenty-first century context of demographic, economic and social transition, and to draw attention to the paradoxical effects of these transitions, whilst taking into account the diverse realities that women are experiencing. The chapter is based mainly on the partial results of three surveys on the social status of women carried out jointly by the All China Women’s Federation and the National Bureau of Statistics in 1990, 2000 and 2010. These surveys paint a wide-ranging picture of the social realities experienced by Chinese women over the last two decades. The chapter concludes that in many respects, Chinese women do not have the same opportunities for social achievement as men and remain largely invested in roles that have a lesser social value than those of men. Different roles and spheres of influence, still clearly identified, continue to be attributed to men and women.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

After three decades of Communism followed by three decades of economic liberalism, Chinese society remains, in many ways, very attached to its social and family traditions (Whyte 2005; Silverstein et al. 2006). In recent years, however, it has shown a remarkable faculty for adapting to the process of globalization in which it is now a stakeholder. Since they can prove difficult to interpret, the transformations that have affected China since the 1980s may sometimes seem perplexing. Indeed, it is not always easy to distinguish between changes that are part of the continuity of longstanding social practices, and others, sometimes sudden, that are the ad hoc expressions of a reaction to the new constraints and opportunities imposed by socioeconomic changes and a globalized society. Indeed, the analysis of social transformations — just as much as economic and political ones — is sometimes so intricate that it quite rightly leads us to conclude that paradoxes exist (Faure and Fang 2008; Rocca 2010; Whyte 2004).

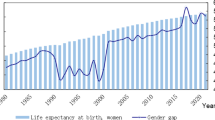

The attitude of Chinese society towards women, also rich in paradox, testifies to this duality — itself all the more complex to understand because still marked by the quest for gender equality that prevailed during the Communist era. Nonetheless, it remains essential to understand and measure transformations in the status of women since the economic reforms if we are to arrive at a more global understanding of contemporary Chinese society, its representations, and the changes it is experiencing. In fact, the place given to women, as measurable using the various indicators of education, employment, demography and health, is a generally reliable indicator of the radical changes affecting society. Yet this is a paradox in itself: although in certain respects, notably regarding education and health, absolute improvement in the situation of Chinese women is indisputable, in others, their relationships with men remain all the more unequal for being part of a demographic context that is unfavourable to them, thereby testifying to an unquestionable deterioration in certain aspects of their situation.Footnote 1

The aim of this chapterFootnote 2 is first, to draw up a socio-demographic inventory of the situation of Chinese women in the prevailing early twenty-first century context of demographic, economic and social transition, and second, to draw attention to the paradoxical effects of these transitions, whilst taking into account the diverse realities that women are experiencing. The chapter is based mainly on the partial results of three surveys on the social status of women (Zhongguo funü shehui diwei chouyang diaocha) carried out jointly by the All China Women Federation and the National Bureau of Statistics in 1990, 2000 and 2010. These surveys (referred to here as ACWF-1990, ACWF-2000 and ACWF-2010), organized with the specific aim of measuring inequality between the sexes and gender differences, paint a wide-ranging picture of the social realities experienced by Chinese women over the last two decades.Footnote 3 These are the only existing surveys on these issues, but their scope is limited by the closed questionnaire data collection method. Yet although they do not provide all the explanations, they nonetheless enable us to understand the processes at work with regard to women and gender relationships. The data from these surveys will occasionally be supplemented by data taken from other sources, notably the 1990, 2000 and 2010 censuses.

1 Women’s Rights and Interests: The Long March of Chinese Women

China is one of the world’s developing countries in which demands for the emancipation of women and the struggle for equality between the sexes are both among the most longstanding political concerns—the first movements in favour of women date back to the mid-nineteenth century (Elisseeff 1988)—and the most in evidence today. As early as the 1950s, practical initiatives were developed to promote women’s work outside the home and the equality of spouses within the family (Johnson 1983). China was also one of the first countries to ratify, in 1980, the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

The relatively early mobilization of the state and civil society partly explains why China now possesses a solid body of legislation for the defence of women’s rights and interests. Thanks to the 1954 Constitution, followed by that of 1982, the law gives men and women equal rights: “Women have the same rights as men in all spheres of political, economic, cultural and social life, including family life”.Footnote 4 This equality of rights and the fight against discrimination have been regularly confirmed, mainly in successive laws on marriage, by the “Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women” (1992) and the “Law on Maternal and Infant Health Care” (1994) (ACWF 2012).

This major mobilization on the part of China goes hand in hand with international initiatives in favour of the autonomy of women and gender equality. In particular, the Chinese government quickly understood that the legitimacy of the country as a leading world power depended on its adhesion to major international principles, notably those relating to the rights of women, and that it was important to support the quest for gender equality in order to ensure harmonious, sustainable development within the globalization process. Besides this, in the 1990s, China became aware that some women had remained on the sidelines of the modernization process and that their situation had, subsequent to the economic reforms, become very unequal, depending on their place of residence and their social class, especially with regard to their needs in terms of subsistence, and the development and preservation of their rights and interests. The Chinese government therefore rapidly echoed the United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (in Cairo in 1994) and the 4th World Conference on women (in Beijing in 1995) which marked a decisive step in the promotion of women’s status in the worldFootnote 5 as did the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).Footnote 6 From then on, the rights and interests of women and their equality with men remained permanently on the political agenda, notably through three successive programmes for the development of women (Zhongguo funü fazhan gangyao) launched from 1995.Footnote 7 Lastly, the political objective of reducing social and economic inequalities, which since the 2000s has been an important element in the development of a “harmonious society” (hexie shehui) may also benefit women, in particular by ensuring a more rigorous application of the laws that protect them and by facilitating access to health, education, social security cover, and employment (Burnett 2010).

The Chinese government’s stance on women’s rights and gender equality has not, however, put an end to traditional stereotypes of the roles and duties of men and women within the family and society, far from it; nor to the often very unequal situations they generate — in particular since the economic reforms (Wang 2010). In 1994, a State Council document (1994) stipulated that: “China subscribes to the principle of gender equality set down in the United Nations Charter and promises to respect it. The Government is convinced that equality between the sexes will become a reality to the extent that women will be able to participate in development as equal partners of men”. (Attané 2005) A decade later, however, the Chinese government recognized that “deep-seated inequalities continue to exist between regions regarding the status of women, traditional gendered stereotypes persist, the rights of women are ignored in many places (and that) a great deal of work remains to be done to improve the situation of Chinese women if their equality with men is to become a reality”.Footnote 8 Even in 2011, the further deterioration of the sex ratio at birth revealed by the sixth census (2010), resulting from massive discrimination against little girls, led President Hu Jintao to confirm the persistence of significant inequalities between the sexes.Footnote 9

2 Education, Employment, Wages: Chinese Women Still Lag Behind

Differences in treatment of men and women are visible in many areas of society. In China, gender inequalities are prevalent not only in access to education, employment and health, but also in the rules of inheritance, wages, political representation and decision-making within the family (Bossen 2007; Tan 2006).

Education is a key factor in improving women’s status in that it tends to reduce the fertility rate and encourages women to take better care of their health (Bongaarts 2003). Above all, by facilitating access to worthwhile, decently-paid jobs, it favours their economic emancipation and in the process — since it changes their power relationship with men — their emancipation within the family. From this point of view, great progress has been made in recent years. Firstly, the spread of primary education amongst the younger generations has significantly reduced the percentage of women aged 18–64 with no education. By 2010 it had fallen to 6.6 % in rural areas and to 3.5 % in urban areas (Table 6.1). Improvements can also be seen in access to secondary and higher education, with a tripling of female enrolment in rural areas between 1990 and 2010, and a doubling of the proportion in urban areas. Although secondary and higher education remain, on the whole, the preserve of a minority of Chinese women (scarcely more than a third of them have access to one and/or the other), recent changes have been undeniably positive: in 20 years, the average length of women’s education has almost doubled, from 4.7 years in 1990 to 8.8 in 2010, thereby gradually narrowing the gap with men, (who had 6.6 years of schooling on average in 1990 and 9.1 years in 2010) (Table 6.1).

Although in urban areas in the east of the country young people of both sexes now have relatively egalitarian access to educational resources, considerable geographical disparities still remain, particularly in rural areas. In 2010, in the centre and west of the country, for example, rural women had attended school for only 6.8 years on average, 2.2 years less than those living in the rural zones of the municipalities of Beijing and Tianjin (ACWF 2010). It is true that in country areas, the added-value of education, in particular for girls, is not always understood, especially now that the costs have become prohibitive for many families since the reform of the education system in the 1980s. As a general rule, family expectations for girls remain lower than for boys, although the gender gap in this respect is narrowing (Adams and Hannum 2008). In fact, the ACWF (2000) survey shows that leaving school early is more frequently the parents’ decision in the case of girls (36.8 %) than in the case of boys (27.9 %). Although financial difficulties remain an important reason for leaving school early for boys as well as girls (for 69.8 and 68.1 %, respectively), more parents nonetheless consider education to be unnecessary for girls (for 9.1 % of girls versus 3.5 % of boys).

Chinese women’s employment situation has also changed radically over the last twenty years, but in a way that is considerably less favourable to them. Although sparse, data from surveys on the status of women — partially supplemented by data from censuses — shows that the female employment rate is still among the highest in the world. In the country as a whole, almost three in four women are in paid employment, a very high level compared with the other large countries in the region. In India, for example, only slightly over one in three women were officially employed in 2009, and in Japan, the Republic of Korea and the Philippines, the figure is below one in two (CILC 2011).

The relative advantage of Chinese women is fragile, however. Indeed, as with men, though to a lesser extent, employment rates for women have fallen significantly since the 1990s, mainly in urban areas. Particularly affected by the redundancies that followed the dismantling of the labour units in the 1990s (Summerfield 1994; Wang 2010; Liu 2007) and with fewer chances than men of finding a new job (Zhi et al. 2012), large numbers of urban women are now returning to the home: in 2010, only 60.8 % were in paid work, compared to 76.3 % in 1990 (Table 6.2). The situation is even more flagrant in certain regions. In 2005, just 45 % of women were in employment in urban Jilin, and in urban Heilongjiang the figure was 35 % (ACWF 2008). Although rural women have not been totally spared by this trend, their effective participation in economic activities (mainly agricultural) remains far greater (82 % in 2010) than in urban areas. The gap between urban areas and the countryside is therefore widening, underlining the extent to which the reorganization and privatization of the Chinese economy, particularly in the industrial sector, is affecting female employment in the cities.

On the whole, while equality with men has never been attained, even during the collectivist period (Johnson 1983), Chinese women have, since the 1950s, gained more economic independence and are to a greater extent mistresses of their own personal and professional choices (Tan 2002; Yan 2006). In particular since the economic reforms, new opportunities have become available to them, in many cases as a result of the boom in higher education, which has enabled women to obtain more qualified and better paid jobs than in the past (Angeloff 2010). A female elite is even emerging, embodied above all by the microcosm of female entrepreneurs whose social success has become one of the symbols of the Chinese economic boom (Song 2011; Deng et al. 2011). This phenomenon apart, the economic reforms have been harmful overall to women, in two ways in particular: first, because they are now more exposed to economic insecurity (linked mainly to unemployment, the difficulty of finding a new job and more frequent compulsory early retirement) than men, and second, because sexual discrimination in the labour market, from which they had been relatively sheltered by the employment system within the labour units, has made the gender equality promised to them, notably by the Constitution, an even more distant prospect (Burnett 1994). The employment market has become highly competitive and is now dominated by men. Many job offers are reserved for men (CERN 2011) and women continue to hit the “glass ceiling” (Angeloff 2010). In addition, unemployment officially remains 50 % higher for women than for men: 12 % and 8 % respectively in 2004 (ACWF 2008), and in 2010, twice as many women as men (10 versus 4.5 % of men) reported being or having been the victim of discrimination in the workplace. For 70 % of the women in this situation, the causes were stated to be unfair dismissal, mainly following marriage or pregnancy, an absence of promotion because of their gender, a lower wage than that of men doing the same work, and the disdain regularly displayed towards them in the workplace (ACWF 2010). Insecurity in the labour market quite logically makes women more vulnerable in economic terms since whilst a large majority of men aged 45–59 (87.1 % in 2010) still live on income earned from work, this is only the case for 65.0 % of women in the same age group. One in five (19.6 %) is financially dependent on a member of her family, versus just 4.7 % of men (PCO 2012).

Although the Communist era favoured the employment of women outside the home, it did not put an end to the social prejudices that place a lower professional value on women’s skills than on those of men (Wei 2011). In 2000, a third of respondents (33.3 % of women and 34.0 % of men) did not refute traditional ideas whereby “man is strong, woman is weak” (Nan qiang nü ruo) or “men’s abilities are naturally superior to those of women” (Nanxing nengli tiansheng bi nüxing qiang) (ACWF 2000). An independent survey (2009) confirmed the prevalence of this way of thinking, revealing that a third of respondents (37 % of men and 33 % of women) consider that if women have fewer career prospects it is because they have limited personal skills; for a further third (32 % of men and 28 % of women) the reason lies in their lack of physical resistance, and for a quarterFootnote 10 (22 % of men and 28 % of women), it is because they are less devoted to their work and their career plan is not sufficiently ambitious. The survey also indicated that the majority of women interviewed (77.6 %) consider that employment opportunities for men and women are unequal, a view shared by the men, but to a lesser degree (66.4 %) (Wei 2011). In addition, even though wage inequalities still exist, to the question “If a man and a woman do the same job but the man is paid more, what is your opinion of the situation?”, 20.5 % of men replied that this was “very common or only natural” (versus 7.9 % of women), 41.8 % thought it “unfair but acceptable” (versus 40.6 % of women) and only 20.0 % considered it “unfair and unacceptable” (42.9 % of women) (Wei 2011).

Chinese society still continues to attribute different and well-defined roles and spheres of influence to men and women. However, as Harriet Evans (2008) has shown, this dichotomy is rarely challenged. In fact the majority of those questioned (61.6 and 54.8 %, respectively, in 2010) continue to think that “men are turned towards society, women devote themselves to their family” (Nanren yinggai yi shehui wei zhu, nüren yinggai yi jiating wei zhu) (Fig. 6.1). Most surprising however, is that agreement with this belief has risen over the last decade amongst both women and men (by 4 and 8 points respectively). Consistent with the previous statement but equally unexpected is the growing agreement with the idea that for women “a good marriage is better than a career” (Gan de hao buru jia de hao). This conviction, now shared by almost half of women (48.0 % in 2010—i.e. 10 points more than in 2000—and 40.7 % of men) reveals the deep-seated internalization of masculine domination, by women even more than by men. Moreover, it reinforces the fact that, unlike in western societies where women’s work outside the home, on a par with that of men, is increasingly judged to be more valuable than domestic labour, no such trend is seen in China (Zuo and Bian 2001). Despite the obvious negative repercussions for the empowerment of women both in economic and symbolic terms, there is a strong move back towards traditional gendered roles. This has been reinforced by women’s growing labour market insecurity — the better qualified included — a situation exacerbated still further by the economic crisis of the late 2000s (Zhi et al. 2012). Women’s insecurity on the labour market, mainly in the cities, is due not only to their growing difficulty in finding employment, but also to the widening gender wage gap. In 1990, the average income of female city-dwellers had reached 77.5 % that of men, but 20 years later it had fallen to just two thirds of the average male income (67.3 %). The relative deterioration in women’s incomes has been even greater in the countryside, where women’s wages relative to men’s fell from 79 % in 1990 to 56 % in 2010. The ACWF-2000 survey shows that in the cities, almost half of working women (47.4 %) earned less than 5,000 yuans a year on average (versus slightly more than a quarter of men: 28.4 %) and just 6.1 % earned more than 15,000 yuans a year on average (versus 12.7 % of men). Moreover, alongside these income differences, women have a slightly longer working day: 9.6 h per day in 2010, compared to 9.0 h for men (ACWF 2010).

Acceptance of gendered roles by men and women (%) (Source: ACWF 2010)

These gender inequalities with regard to levels of income and working hours are mainly due to the type of employment occupied, with most women working at unskilled, low-paid jobs in agriculture, the manufacturing industries, transport, shops or services (Tan 2002; Zhi et al. 2012) (Table 6.3). The feminization of the agricultural workforce partly explains these increasing differences in income: in 2000, 82.1 % of rural women were employed full-time in agricultural activities (compared to 64.7 % of men) (ACWF 2010).

3 Women in Private Life: Roles Still Firmly Gendered

Private life is a place where, doubtless to an even greater extent than in public life, the status of Chinese women has changed both for better and for worse. In many ways, particularly as regards their reproductive health (see Inset 6.1), fertility control and participation in household decision-making, their overall situation has unquestionably improved. The place of women in the family, firstly as girls and then as wives, remains nonetheless subject to various influences which do not always work to their advantage.

Inset 6.1 Considerable Progress in Reproductive Health

Access to health care and its impact on the well-being and survival of individuals are markers of a society’s level of development. Maternal mortalityFootnote 11 is a good indicator of the extent to which women receive health care and hence their place in public health policies. The implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (see p. 97) led to various national initiatives which have significantly reduced maternal mortality in recent years. In 2008, China recorded 38 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, a very privileged position compared to that of its main neighbours. In the same year, India, for example, recorded a rate of 230 per 100,000, Indonesia, 240 and Bangladesh, 340. However, China remains well below the level of its more developed neighbours such as South Korea (14 per 100,000) and Japan (6 per 100,000) (UNICEF 2008).

The significant decrease in the maternal mortality rate, which has fallen by more than 5 % a year on average since the early 1990s (Table 6.4), is due mainly to the almost universal adoption of hospital births, which have risen from a little over 40 % in the mid-1980s to more than 90 % today (Feng et al. 2010).Footnote 12 It is also the result of better antenatal care, including in rural areas, where in 2010 almost nine in ten pregnancies (89.4 %) received medical follow-up. However, although maternity no longer represents a significant risk for the survival of Chinese women, these overall achievements have not been matched throughout the country.

In rural areas, while maternal mortality fell by more than a third between 1991 and 2004, the rate remains more than double that of urban areas (Table 6.4). In 2006, it had fallen to below 10 per 100,000 in Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin, i.e. to a level close to that of Asia’s most developed countries, but remained eight times more frequent in the rural areas of Gansu (76), Guizhou (83), Qinghai (99), Xinjiang (107), and at a very high level in Tibet (246). These disparities are due partly to the fact that hospital births are still uncommon in some rural areas. In 2006, a third of all births took place at home for women in rural Gansu (33 %), half of births in rural Guizhou (49 %) and two-thirds in rural Tibet (64 %) (MOH 2007). Moreover, data from ACWF-2010 indicate that, in the west and centre of the country, almost half of all rural women (43.4 %) had not had a gynaecological examination in the three years preceding the survey (compared to 17.8 % in the rural zones of Beijing, Tianjin and Shanghai and 39.1 % in the rest of the eastern region) (Fig. 6.2).

I.A.

On the whole, Chinese women express a high level of satisfaction with their status in the household (in 2010, 85.2 % reported being satisfied or very satisfied in this respect) and with the different roles of men and women. However, some of these women (and in total, a quarter of those questioned in the same survey: 24.7 %) reported experience of domestic violence, i.e. verbal and/or physical violence, of restriction of personal liberty, economic control and/or forced sexual relations (ACWF 2010). Other indicators made available by the ACWF surveys also show that the spouses’ roles remain deeply gendered and that women clearly remain under the control of their husbands in many respects. In particular, they are not systematically involved in domestic decisions, although the situation has certainly improved in recent years. In 2010, three married women in four took part in important household decisions about bank loans or financial investments (74.7 versus 50.5 % in 1990) and an equivalent percentage had a say in the decision to buy or build a family home (74.4 versus 65.6 % in 1990). Nevertheless, only one women in seven (13.2 % in 2010) was a home-owner in her own right (four times fewer than men: 51.7 %) and one in four (28.0 %) in co-ownership with her husband (compared to 25.6 % of men). Equality between single men and women is also far from being achieved: one unmarried man in five (21.8 %) owns his own home, compared with one unmarried woman in fifteen (6.9 %). This state of affairs is related to the above-mentioned gender wage gap, which clearly results in unequal access to financial resources and property, together with the social pressure to buy a home, which is less acute for women than for men (Attané 2011; Osburg 2008). It also illustrates the persistence of strong patriarchal traditions, which although they invariably favour the male line, continue to influence family habits, particularly as regards inheritance. For example, although enshrined in Chinese law, women’s right to inherit in the same way as men is still not widely respected (Bossen 2007) and is not even universally accepted. The ACWF-2000 survey indicates that only around one person in four (23.6 % of women and 28.1 % of men, compared to 16.2 and 21.5 %, respectively, 10 years earlier) considers that married brothers and sisters have an equal right to inherit. Moreover, an equally small proportion are favourable to a child taking his or her mother’s surname: 34.2 % of women in 2000 (twice the 1990 figure of 17.1 % all the same) and 21.2 % of men (an increase of 7.0 points).

These different results confirm the deep-seated internalization of gendered roles in Chinese households and their tacit acceptance by the majority of women and men. For example, the division of domestic work remains very unequal, even in households where both husband and wife work. In 2010, the average time spent on domestic tasks by working women each day was 2.5 to 3 times longer than the time spent by men (Table 6.5). However, the majority of married men and women do not really challenge this division of tasks (Zuo and Bian 2001). Overall, the role of the husband as the breadwinner and that of the wife as centred on the home and domestic tasks remains firmly anchored not only in marital practices but also in the spouses’ expectations of each other (Evans 2008). These differentiated expectations may therefore explain the unequal access of men and women to educational, financial and inherited resources, thus perpetuating gender differences. They could also help understand why, on a labour market that has become highly competitive, the work of Chinese women serves, as elsewhere (Battagliola 2004), as an adjustment variable. When jobs are scarce, family arbitration usually favours the man’s job and sacrifices that of the woman, whose contribution to the family income is generally secondary (Zhi et al. 2012). Women therefore find themselves in competition with men for jobs twice over, once on the labour market and again within the home.

The anchoring of gendered roles in Chinese households is also due to the persistently high value placed on maternity, despite the dramatic drop in fertility over the last few decades. Yet low fertility is supposedly favourable to the emancipation of women (Oppenheim Mason 2000), for two main reasons, firstly because it mechanically reduces the risks linked to pregnancy and therefore improves their health and reduces maternal mortality, and secondly, because it gives them more opportunity to engage in activities outside the domestic sphere. Free from the constraints of looking after a large family, women are theoretically more available to take up paid employment, which in turn gives them greater economic and domestic autonomy. After four decades of birth control, China has distinguished itself in this respect. Fertility there has now attained a comparable, or even lower, level than that of the most developed countries (around 1.4–1.5 children on average in China in 2010),Footnote 13 compared wih 2.3 in 1990 and almost six in 1970. However, reduced fertility has not been accompanied by an increase in the number of working women, quite the contrary. As female labour force participation was already exceptionally high in the 1970s, potential for growth is limited and the negative correlation effect usually observed between these two phenomena cannot operate. Moreover, the effects of the fertility decline on women’s employment have been largely counterbalanced by the liberalization of the labour market and state disengagement from childcare provision, with a steep rise in the cost of bringing up children, notably in matters of day care, health and education, making the reconciliation of family and working life increasingly difficult and costly. Paradoxically, even though most Chinese families are now very small, children constitute an increasing obstacle to employment for Chinese women (Attané 2011). Moreover, the family planning programme continues to impose major restrictions on women (notably that of compulsory contraception and the negation of personal fertility desires), thereby limiting their empowerment at individual and family levels.

Notes

- 1.

See for instance Chap. 5 in this book.

- 2.

This chapter is the partial reproduction of an article published in the Academic Journal China Perspectives in late 2012 (Attané 2012).

- 3.

These surveys in the form of questionnaires were each given to representative samples of tens of thousands of women and men aged 18–64 from different provinces and communities (urban, rural, population with experience of migration, Han/ethnic minorities, etc.). The quantitative data obtained was supplemented by information taken from in-depth interviews and discussion groups. For more details on the samples and methodology of these surveys, see ACWF (2000) and ACWF (2010). With no access to raw data, the results presented here were taken from the Executive reports.

- 4.

Excerpt from Chap. 48 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, 1982.

- 5.

“The emancipation and empowerment of women and improvements in their political, social, economic and health status is an end in itself”; “The fundamental rights of women and girls are inalienable and indivisible from the universal rights of Man” (Excerpts from the Program of Action of the 4th World Conference on Women held in Beijing, 4–15 Sept 1995).

- 6.

The member-states of the United Nations agreed on eight essential goals to be reached by 2015. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are the following: to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; to achieve universal primary education; to promote gender equality and empower women; to reduce infant mortality; to improve maternal health; to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases; to ensure environmental sustainability; to develop a global partnership for development.

- 7.

These three programmes of action for women’s development covered, respectively, the three following periods: 1995–2000, 2001–2010 and 2011–2020. See for instance Program for the Development of Chinese Women 2001–2010. Available at . Accessed 10 Nov 2013.

- 8.

Gender Equality and Women’s Development in China, available on China.org.cn, China Publishes Gender Equality White Paper. Available at www.china.org.cn/english/2005/Aug/139404.htm. Accessed 25 Sept 2012.

- 9.

Census data demonstrates positive changes in China over the past decade. Available at http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90001/90776/90882/7366454.html. Accessed 25 Sept 2012.

- 10.

All the causes have not been given here. In total, all the causes combined exceed 100 % because several answers could be given.

- 11.

The maternal mortality rate measures the number of mothers who die in pregnancy, or during or after childbirth, per 100,000 live births.

- 12.

Since the mid-2000s, the Chinese Ministry of Health has set up a benefits system for pregnant women in rural areas. The benefit of 500 yuans (around 50 €) is intended to meet the cost of a hospital birth. It is one of the measures introduced to combat infant and maternal mortality under the MDGs (see above). See: China lowers maternal death through subsidizing hospital delivery. 9 Sept 2011. Available at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-09/09/c_131129666.htm. Accessed 13 Sept 2012.

- 13.

Zhongguo xianru chao di shengyulü xianjing (China falls into the trap of the lowest-low fertility). Nanfang zhoumou, 24 May 2011. Available at . Accessed 25 Sept 2012.

References

ACWF (All China Women Federation). (2000). Di er qi Zhongguo funü shehui diwei chouyang diaocha zhuyao shuju baogao (Executive report of the second sample survey on Chinese women’s social status). http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjgb/qttjgb/qgqttjgb/t20020331_15816.htm. Accessed 25 Sept 2012.

ACWF (All China Women Federation). (2008). Annual report on gender equality and women’s development in China. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

ACWF (All China Women Federation). (2010). Di san qi Zhongguo funü shehui diwei diaocha zhuyao shuju baogao (Executive Report of the third sample survey on Chinese women’s social status), Funü yanjiu lun cong, 6(108).

ACWF (All China Women Federation). (2012). Laws and regulations. http://www.women.org.cn/english/english/laws/mulu.htm. Accessed 9 Nov 2013.

Adams, J., & Hannum, E. C. (2008). Girls in Gansu, China: Expectations and aspirations for secondary schooling. http://repository.upenn.edu/gansu_papers/4. Retrieved 25 Sept 2012.

Angeloff, T. (2010). La Chine au travail (1980–2009): Emploi, genre and migrations. Travail, genre and sociétés, 1(23), 79–102.

Attané, I. (2005). Une Chine sans femmes? Paris: Perrin.

Attané, I. (2011). Au pays des enfants rares. La Chine vers une catastrophe démographique. Paris: Fayard.

Attané, I. (2012). Being a woman in China today: A demography of gender. China Perspectives, 4, 5–15.

Battagliola, F. (2004). Histoire du travail des femmes. Paris: La Découverte.

Bongaarts, J. (2003). Completing the fertility transition in the developing world: The role of educational differences and fertility preferences. Policy research division working papers, 177. New York: Population Council. http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/wp/177.pdf. Retrieved 25 Sept 2013.

Bossen, L. (2007). Missing girls, land and population controls in rural China. In I. Attané & C. Z. Guilmoto (Eds.), Watering the neighbour’s garden: The growing demographic female deficit in Asia (pp. 207–228). Paris: Cicred.

Burnett, J. (2010). Women’s employment rights in China: Creating harmony for women in the workplace. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 17(2). http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol17/iss2/8. Retrieved 25 Sept 2012.

CERN (China education and research network). (2011). Nü daxuesheng jiuye kunjing diaocha: Liu cheng ceng zaoyu xingbie xianzhi (Survey on the employment of male college students: 60 % have experienced gender-related limitations). http://edu.sina.com.cn/j/2011-07-27/1357205033.shtml. Retrieved 25 Sept 2012.

CILC. (2011). Charting international labor comparison, 2011 edition. Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. http://www.bls.gov/fls/chartbook/section2.pdf. Retrieved 25 Sept 2012.

Deng, S. L., Xu, W., & Alon, I. (2011). Framework for female entrepreneurship in China. International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets, 3(1), 3–20.

Elisseeff, D. (1988). La femme au temps des Empereurs de Chine. Paris: Stock.

Evans, H. (2008). The subject of gender: Daughters and mothers in urban China. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Faure, G. O., & Fang, T. (2008). Changing Chinese values: Keeping up with paradoxes. International Business Review, 17(2), 194–207.

Feng, X. L., Zhu, J., Zhang, L., Song, L., Hipgrave, D., Guo, S., Ronsmans, C., Guo, Y., & Yang, Q. (2010). Socio-economic disparities in maternal mortality in China between 1996 and 2006. BJOG, 117(12), 1527–1536.

Johnson, K. A. (1983). Women, the Family and Peasant Revolution in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Liu, J. Y. (2007). Gender and work in urban China, women workers of the unlucky generation. London: Routledge.

MOH (Ministry of Health). (2007). Zhongguo jiankang nianjian (China Health Yearbook). Beijing: Zhonghua renmin gonghe guo weisheng bubian, zhongguo xie he yike daxue chubanshe.

NBS. (2007). National Bureau of Statistics, 2005 nian quanguo 1 % renkou chouyang diaocha zhuyao shuju (Data of the 2005 1 % Sample Survey). Beijing: Zhongguo tongji chubanshe.

Oppenheim Mason, K. (2000). Influence du statut familial sur l’autonomie and le pouvoir des femmes mariées dans cinq pays asiatiques. In M. E. Cosio-Zavala & E. Vilquin (Eds.), Statut des femmes and dynamiques familiales (pp. 357–376). Paris: Cicred.

Osburg, J. L. (2008). Engendering wealth: China’s new rich and the rise of an elite masculinity. Chicago: The University of Chicago.

PCO (Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China). (1993). Zhongguo 1990 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 1990 population census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: Zhongguo renkou chubanshe.

PCO (Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China). (2002). Zhongguo 2000 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 2000 population census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: Statistics Press.

PCO (Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China). (2012). Zhongguo 2010 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 2010 population census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: Statistics Press.

Rocca, J.-L. (2010). Une sociologie de la Chine. Paris: La Découverte.

Silverstein, M., Zhen, C., & Li, S. (2006). Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: Consequences for psychological well-being. Journal of Gerontology, 61(5), 256–266.

Song, J. (2011). China’s female entrepreneurs dare to try. China Daily, 15 Dec 2011.

Summerfield, G. (1994). Economic reform and the employment of Chinese women. Journal of Economic Issues, XXVIII(3), 715–732.

Tan, L. (2002). Quel statut pour la femme chinoise?. In I. Attané (Ed.), La Chine au seuil du xxi e siècle: questions de population, questions de société (pp. 329–348). Paris: INED.

Tan, L. (2006). Zhongguo xingbie pingdeng yu funü fazhan pinggu baogao 1995–2005 (Report on gender equality and women’s development in China 1995–2005). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

UNICEF. (2008). Information by country and programme. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry. Accessed 25 Sept 2012.

Wang, Z. (2010). Gender, employment, and women’s resistance. In E. J. Perry & M. Selden (Eds.), Chinese society: Change, conflict and resistance (pp. 162–186). London: Routledge.

Wei, G. (2011). Gender comparison of employment and career development in China. Asian Women, 27(1), 95–113.

Whyte, M. K. (2004). Filial obligations in Chinese families: Paradoxes of modernization. In C. Ikels (Ed.), Filial piety: Practice and discourse in contemporary East Asia. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Whyte, M. K. (2005). Continuity and change in urban Chinese family life. The China Journal, 53, 9–33.

Yan, Y. (2006). Girl power: Young women and the waning of patriarchy in rural North China. Ethnology, 45(2), 105–123.

Zhi, H., Huang, J., Huang, Z., Rozelle, S., & Mason, A. (2012). Impact of the global financial crisis in rural China: Gender, off-farm employment, and wages. Center for Chinese Agricultural Policy. http://en.ccap.org.cn/show.php?contentid=3719. Accessed 25 Sept 2012.

Zuo, J., & Bian, Y. (2001). Gendered resources, division of housework, and perceived fairness—case in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 1122–1133.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Conclusion

Conclusion

Chinese women do not, as famously formulated by Mao, hold up “half the sky”. Their rights and interests are nevertheless increasingly protected by law, and the fight for gender equality regularly brings new victories. However, the recent social changes are extremely complex. The highly gendered roles that still exist within the couple in China are part of a continuum of inequality between the sexes that continues throughout life. From this point of view, demographic trends, which are closely dependent on the prevailing family and social norms, shed special light on the situation of Chinese women. While Chinese girls are studying longer at school — almost as long as boys among the younger generations — the persistence of deeply entrenched gendered roles in the workplace and family life continues to limit their autonomy and contributes to the social reproduction of gender inequality. This is particularly obvious in the early stages of life, as sons are still preferred over daughters in many families, as demonstrated by Li, Jiang and Feldman’s chapter in this book.

The disengagement of the state in key areas such as employment, social security, education, and health leaves families to fend for themselves and exacerbates socioeconomic inequalities. The population, more vulnerable as a whole, is obliged to develop new strategies for meeting its own needs and getting the best out of the transformations that are taking place. At the same time, while Chinese legislation remains among the most advanced in the developing world with regard to promoting gender equality, and while there are many initiatives in favour of women, society only gives them relative autonomy, limited in particular by their lesser access to resources (notably educational, financial, and inherited assets) in comparison to men.

In many respects, Chinese women do not have the same opportunities for social achievement as men and remain largely invested in roles that have a lesser social value than those of men. The roles and spheres of influence attributed to men and women thus remain clearly differentiated. But China is not really a textbook case. Indeed, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the question of women and equality between the sexes remains a priority on the international political agenda, and with good reason. Rare are the countries (does one even exist?) that offer conditions of perfect equality between women and men in areas as varied as access to health care, education, and employment, wages, political representation, representation of assets or, in private life, family decision-making and the division of domestic tasks.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Attané, I. (2014). Being a Woman in China Today: A Demography of Gender. In: Attané, I., Gu, B. (eds) Analysing China's Population. INED Population Studies, vol 3. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8987-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8987-5_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-8986-8

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-8987-5

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)