Abstract

China’s sex ratio at birth has been increasing since the 1980s, and the resulting male surplus in China’s marriage market has been widely discussed. In this chapter we first review the sex ratio at birth by province in the four Chinese censuses and calculate the proportion of single males and females and their ratio. Using the 2010 census data, we then project the marriage squeeze sex ratio of first marriage partners, as well as the male surplus in China’s future. We explore the potential impact of the male surplus on families of single men, communities, public health, and violent behavior, in addition to the effect of the female shortage on potential improvement of female social status.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

China’s male-biased sex structure has drawn a great deal of attention both in China and abroad. In particular, the male marriage squeeze resulting from the shortage of women of marriageable age raises many questions concerning its demographic and social impacts. This male marriage squeeze is expected to worsen after the 2010s due to the increase in the sex ratio at birth (SRB) from the 1980s. There will be a group of “bare branches”, namely men mostly at the bottom of the Chinese social hierarchy, who will face a high probability of remaining lifelong bachelors (Chen 2006).

The potential impact of this surplus of males on China’s socioeconomic development has been widely discussed (Attané 2013; Edlund et al. 2007; Ebenstein and Sharygin 2009; Wei and Zhang 2011), and some scholars have even considered its potential impact on security issues (Hudson and den Boer 2004; Poston et al. 2011). In this chapter, we attempt to estimate the male surplus in China’s population of marriageable ages in the coming decades, and make some assumptions about its possible impact on society, individuals, and especially women.

2 The Deteriorating Sex Ratio at Birth

Among the demographic factors affecting sex distribution among adults are the sex ratio at birth (SRB), overall age structure, mortality differences between males and females, and international migration. In China, the sex ratio at birth, which became increasingly imbalanced in favour of boys from the 1980s, is a major factor, although it will affect the adult sex structure only in the decades after 2010, when male-biased cohorts born from 1980 will enter the marriage market.

The imbalanced sex ratio at birth is the result of declining fertility and deeply entrenched son preference, leading to significant discrimination against daughters, combined with the spread of modern technologies for prenatal sex-selection. Male heirs play dominant economic and social roles in China’s patriarchal system: sons provide labour for fieldwork or family enterprise, and traditionally support their elderly parents. Cultural traditions dictate that only sons can continue the family line and enhance the family status. As a result, Chinese families still manifest a strong preference for sons, and increasingly discriminate against daughters because, in the context of low fertility imposed by the family planning policy, a daughter may deprive them of the possibility of having a son (Attané 2013). Recent changes in reproductive behaviour and the growing numbers of small families have also favoured son preference. With the rising cost of living and changing lifestyles, more and more couples are spontaneously limiting the number of their children, and there is a growing trend to select the child’s sex prior to birth. This has produced the significant increase in the SRB observed since the 1980s, as shown in Fig. 5.1.

The imbalance in the sex ratio at birth, perceptible at the national level from the early 1980s, became manifest in the overwhelming majority of China’s provinces in the following decades. It did not arise everywhere at the same time, however, and there are considerable regional differences in the speed of its increase (Fig. 5.2). In the 1982 census, the sex ratio at birth at the national level was still almost normal, at around 107 boys per 100 girls, but it was already deviating from the norm of 105–106 in some provinces. In Anhui, Guangdong, Guangxi, Shandong and Henan, it had already reached or even exceeded 110 in 1982. From then on, the situation continued to deteriorate in most provinces, except the sparsely populated western provinces, to the point that it exceeded 120 in 11 provinces in 2000.

The situation did not change radically between the last two population censuses in 2000 and 2010. The one-point increase observed in the sex ratio at birth at the national level over this period (from 116.9 to 117.9 boys per 100 girls) conceals some convergence of the ratios at the provincial level: the sex ratio at birth declined in all the provinces where it was above 120 in 2000 (Anhui excepted) while increasing in all those where it was below 110 in 2000. However, it still exceeded 120 in one-third of the provinces in 2010; China’s sex imbalance at birth thus remains extremely abnormal and therefore worrisome.

While the sex ratio at birth reached new highs during the mid-2000s, exceeding 120 boys per 100 girls against the normal value of 105–106, it has decreased slightly in the most recent years. According to the National Population and Family Planning Commission, the sex ratio at birth has declined for four consecutive years, dropping from 120.6 in 2008, to 119.5 in 2009, 117.9 in 2010, 117.8 in 2011, and 117.7 in 2012 (Li 2013). However, it is uncertain whether it will remain around 120 or continue to fall, as optimistically anticipated by some scholars (Das Gupta et al. 2009; Guilmoto 2012).

3 The Growing Numerical Sex Imbalance Among Adults

3.1 Proportions of Never-Married by Sex and Age Group, and Sex Ratio of the Unmarried

The proportion of unmarried by sex and age group among adults, and the corresponding sex ratios in 1990, 2000, and 2010, are shown in Table 5.1. It appears that while the observed sex ratios are usually approaching equilibrium at around 100 men per 100 women by the ages of 30–40, men recurrently outnumber women both in the total and the unmarried population. This shortage of women, especially among the unmarried, is partly the consequence of excess female mortality that prevailed during most of the twentieth century. It is also the result of the decreasing size of annual birth cohorts over the past decades, which has led to a mechanical decrease in the sex ratio of people reaching marriageable age, given the age gap between spouses at marriage (Attané 2013). In 1990, 5.1 % of men aged 45–49 were unmarried, compared to only 0.2 % of women, and the ratio of unmarried males to unmarried females in this age group was 3,191 to 100. In 2000, 4.0 % of males aged 45–49 were unmarried, versus only 0.2 % of females in this age group, and the number of unmarried males was 20 times higher than that of the corresponding female group (2004 to 100). In 2010, the percentages were 3.2 % and 0.4 %, respectively, and the ratio was 714 to 100.

3.2 The Never-Married are Mainly Males, Concentrated in Rural Areas, and with a Low Educational Level

The proportions and the sex ratios of never-married by place of residence, namely cities, towns, and rural areas, are shown in Table 5.2. Clearly, there is a much more pronounced numerical imbalance between unmarried men and women in rural areas (as the sex ratio in 2010 is far beyond the normal range, at 166.6 unmarried men per 100 unmarried women in the age-group 20–49, even reaching 1,547 for the group aged 45–49). An imbalance also exists in towns and cities, with a sex ratio among the never-married reaching 614 for the age group 45–49 in towns, nearly three times the level of 256 observed in cities.

It appears from Table 5.3 that the proportion of never-married males over the age of 25 and the sex ratios in each age group are highest among those with a low educational level (primary school) or no education, while men with at least secondary education are almost all married by the age of 35. Particularly striking is that more than one in three men with no education are still unmarried beyond age 40, and are therefore very likely to remain lifelong bachelors (Attané et al. 2013). Among men with at least secondary education, the percentage of never-married drops to 5 % or less beyond age 35, meaning that almost all men who have completed at least the 9 years of compulsory education and plan to marry succeed much more frequently than the others in doing so.

As evidenced by various studies, both in China and abroad, the men most likely to remain lifelong bachelors live mostly in rural areas, and have low educational levels (Li et al. 2010). This indicates that the marriage market in rural areas and among the less advantaged male socioeconomic groups is clearly affected by hypergamy, as women exercise their preference for a spouse of higher socioeconomic status (Attané 2013). In cities and towns, however, where men have better socioeconomic conditions on average, the male surplus is attenuated by immigration from rural areas of women searching for a wealthier spouse in the more developed and urbanized regions. As a consequence, the shortage of women in the marriage market tends to be felt mainly in poverty-stricken areas, and among men living in poor socioeconomic conditions (Li et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2012).

4 Future Trends in the Male Marriage Squeeze

An individual’s decision to marry or not and the mate selection process are influenced by various social, economic, and cultural criteria. But they are also affected by demographic circumstances, and in particular by the respective numbers of women and men in the marriage market.

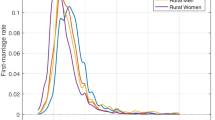

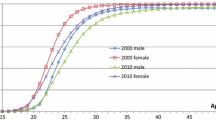

In a previous study, Jiang et al. (2011) calculated the sex ratios of potential first-marriage partnersFootnote 1 to estimate the extent of the marriage squeeze in the whole population of marriageable age regardless of marital status.Footnote 2 The estimates presented in Figs. 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5 apply these potential first-marriage sex ratios to the 2010 census data. Even if the results are to some extent affected by possible under- or over-counts at the 2010 census (Tao and Zhang 2013), they nonetheless provide strong evidence of the upcoming sex imbalance on the marriage market, with the potential first-marriage sex ratio reaching 1.19 men per woman in 2020 and peaking at 1.25 in 2035 before falling steadily thereafter under our assumption of a declining sex ratio at birth as early as 2010.

Figures 5.4 and 5.5 display logically similar trends to those evidenced in Fig. 5.3 It appears from our calculationFootnote 3 that there will be more than 1 million surplus males in the marriage market each single year between 2016 and 2046, and that their number will even exceed 1.4 million annually in the two five-year periods 2018–2023 and 2031–2036. Starting from the late 2010s, the male surplus will exceed 15 %, peaking at 17 %–20 % between 2030 and 2047.

5 The Male Marriage Squeeze and its Implication for Society and Individuals

In Chinese society today, heterosexual marriage remains a social prerequisite for marital-type cohabitation and family formation (Attané et al. 2013). As great store is set on marriage, failing to marry affects many aspects of an individual’s life (Li et al. 2010). In addition, in the traditional family, a young man’s marriage is not just a personal matter but is important for his family and the local community as well. As a result, being unable to marry and therefore remaining a lifelong bachelor can have multi-dimensional consequences for the men concerned (Attané et al. 2013).

5.1 Impact of Lifelong Bachelorhood on Bachelors Themselves and Their Families

Marriage in China is not only a matter of “personal face” but also involves the family’s honour and the continuity of the family line. Although an increasing number of young adults in urban areas are now making the choice to delay marriage or remain single, for most men in rural areas, the failure to marry is still socially stigmatized: it not only creates feelings of isolation and social uselessness for the men themselves (Attané et al. 2013; Li et al. 2010), but also has negative impacts on their families’ social status in the community (Jiang and Sánchez Barricarte 2013).

Available research indicates that lifelong male bachelors in rural areas have a lower level of life satisfaction than married males, as they have no one to share their daily life and take care of them. In addition, they have higher rates of depression than married males, often because of the tremendous social pressure to marry exerted upon them by their immediate family and other relatives, especially if they are the oldest son (Li et al. 2009; Attané et al. 2013), to the extent that some of them are even driven to suicide (Jiang and Li 2009). In their village community, lifelong bachelors are often treated differently from married men, and sometimes suffer from social exclusion as they tend to participate less in the main events of social life, such as funerals and weddings, and have fewer social interactions with their peers than married men.

Another issue for lifelong bachelors concerns their old age. In Chinese culture, the elderly are traditionally supported by their offspring, generally their sons. But in rural China, no marriage overwhelmingly means no children, and therefore no old-age support as there is no universal pension system. In addition, parents are likely to receive less economic support from an unmarried son in their old age, as most lifelong bachelors are themselves in poverty (Attané et al. 2013; Jiang and Li 2009).

Chinese parents consider a child’s marriage as one of their biggest responsibilities, and to achieve this goal they may have to save every penny, sometimes taking out large loans to pay a bride-price or even to illegally “purchase” a trafficked woman for their son (Jiang and Sánchez-Barricarte 2012). As a consequence, parents who fail to marry their child, in particular their son, are often looked down upon, suffer from discrimination within their community, and therefore have feelings of social inferiority and helplessness with respect to the son who cannot marry. Further, as older unmarried males have little to do all day, problems with gambling and alcohol abuse may arise, causing psychological distress to their families (Xu and Liang 2007). Some parents blame themselves for not fulfilling their duties, and family relations may become strained as family members quarrel about the son’s marriage (Jiang and Li 2009). Such great store is set on marriage in rural China that men who cannot find a spouse by resorting to traditional channels adjust their marriage strategy and lower their standards for a spouse. In particular, the male marriage squeeze may challenge the social stigma on widowed and divorced women’s remarriage. One mother of an unmarried man explains, for instance, that she would be happy for her son to find a wife, whatever her status may be, e.g. widowed, divorced, or even disabled (Mo 2005). Sun (2005) suggests that alternative forms of marriage, such as child brides, or exchanging girls as brides between two families, may become more frequent in poverty-stricken areas. Commodification and trafficking of women may also expand due to increasing demand for brides by rural unmarried men (Attané 2013).

5.2 The Influence on Local Community

There have been many recent reports on the existence of “bare-branchFootnote 4 villages”, i.e. villages where a significant share of the male population is still unmarried and unlikely to marry in the future. In a mountain village in south-western Guizhou, there are 2,249 inhabitants in total, with 282 “bare branches” accounting for 20 % of all men (He 2007). In Yanbian prefecture in Jilin, there are more than 13,000 “bare branches”, and it is not uncommon to see two or three in a single family (Xu and Liang 2007). In a village in central Hubei, “bare branches” account for more than 10 % of the village population, with one in almost every household (Wang et al. 2008).

At local level, the numerical sex imbalance among young adults is often aggravated by differential migration. In Qitai county in northwest Xinjiang province, for instance, among the 400 or so young people who have migrated to cities since 1993, 75 % are women. One village official explained: “There are 4,000 inhabitants in our village, and more than 400 men have been unable to marry. We are a suburban village which is short of women although conditions are good”. Thus, it is not just the remote poor villages that are likely to experience a male marriage squeeze (Zhong and Liu 2006).

Female internal labour migration increased significantly from the late 1980s, together with the gradual expansion of the marriage radius for rural women, who more and more frequently marry a man outside their home county, city, or province (Tan et al. 2003). As is the case for rural men, the push factors underlying female migration are linked to poor local living conditions: inadequate transportation, economic backwardness, and difficulties in improving living standards (Shi 2006). While labour migration can to some extent satisfy rural women’s desire for a better life and personal development, in the long run marriage migration to more well-off and urbanized regions often becomes a strategy for upward social mobility among women in poor rural areas. As a consequence, men living in the more remote and underdeveloped rural areas are at a disadvantage in the squeezed marriage market, because their geographical location and poor economic conditions are not attractive to local women. Even when these men migrate temporarily to cities to get better jobs, they often return to their hometown on a seasonal basis and, due to their low level of skills and education, are unable to settle permanently in the city. In the context of numerical sex imbalance on the marriage market, these men therefore form the most vulnerable groups in terms of marriage opportunities (Shi 2006). Their chances of marrying may be even further compromised by an inability to meet the rising costs of marriage – including bride price and the costs of the ceremony itself (Attané et al. 2013). In China as in other societies, poverty tends to exclude the poorest section of the male population from marriage (Li et al. 2010)

At the community level, the emergence of “bare-branch” groups may have various consequences. A survey conducted in 364 villages from 28 provinces nationwide indicates that these lifelong bachelors are often negatively perceived: they are regularly accused of gambling, stealing, making local women engage in non-marital love affairs with them, and even causing social anomie (Jin et al. 2012).

5.3 Potential Effects on Public Health

In societies with male-biased sex ratios, a significant increase in the numbers of male bachelors is said to be an important driving force in the development of the sex industry and prostitution (Courtwright 2001). Given the Chinese context, in which condom use is extremely infrequent, the development of commercial sex may lead to the spread of sexually transmitted diseases (Hershatter 1997).

Lacking a stable sexual partner within heterosexual marriage, male bachelors resort more frequently to commercial sex with prostitutes (Merli et al. 2006; Li et al 2010). In a survey conducted in Anhui Province in 2008, 30 % of the interviewees admitted paying for sex at least once, and the proportion whose first sex or last sex was with a sex worker was six to seven times higher than for the married male respondents. This could provide an opportunity for the spread of HIV, with the bare branches becoming HIV carriers as they seldom use condoms (Zhang et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2012). Chen et al. (2007) analysed HIV rates among a sample of patients being treated for sexually transmitted infections in 14 clinics in Guangxi and concluded that “China’s imbalanced sex ratios have created a population of young, poor, unmarried men of low education who appear to have increased risk of HIV infection”.

Models that take account of the male-biased sex structure and the prevalence of unprotected sexual intercourse between male bachelors and sex workers show that the HIV infection rate will increase rapidly, although estimated rates vary (Merli et al. 2006; Ebenstein and Sharygin 2009). The more pessimistic scenarios indicate that the adult HIV-positive prevalence rate may rise to 3 % by 2050 (Merli et al. 2006).

5.4 Potential Impact on Violent Behaviours

Some studies support the idea that anti-social behaviours, such as violence and even criminality may be positively correlated with the male surplus, and suggest that crime rates are much higher among unmarried men than among married ones (Mazur and Michalek 1998). For India, which also has a surplus of males in its adult population, Dreze and Khera (2000) suggest that, after controlling for other related variables such as urbanization and poverty, the sex ratio is positively correlated with murder rates; the higher the male surplus, the higher the crime rate. In analysing the data in 26 provinces of China from 1988 to 2004, Edlund et al. (2007) also found that the sex ratio of the population aged 16–25 has a significant impact on crime levels: when the sex ratio increases by 3 %, crimes of violence and against property rise by about 3 %. A correlation between male surplus and the prevalence of crime, which has been evidenced on the basis of national data in 70 countries (Barber 2000), is also anticipated for China (Hudson and den Boer 2004). According to these authors, males who cannot marry, and who are mostly at the bottom of the social hierarchy, may tend to resort to violence to get what they cannot obtain through legal channels. Although convincing evidence of this relationship is still lacking, some research indicates that as they age, male bachelors sometimes suffer from psychological impairment that could lead to violent behaviours (Peng 2004).

5.5 Can the Female Shortage Improve Women’s Social Status?

When there is a male surplus in the marriage market, one expects women to be in a stronger position: they can increase their bargaining power in regions with a significant male-biased sex imbalance, and have a greater say in household decisions and investments (Porter 2009). Research in Vietnam has also confirmed that the shortage of women in some regions has improved their bargaining power in marital transactions (Bélanger 2011).

In China’s patriarchal and patrilocal system, bride-price occupies a central position in the marriage process, so competition for women is leading to bride-price inflation (Becker 1991). In order to increase their chances of attracting a potential wife in a very competitive marriage market, men must pay a higher bride-price, which appears to be closely connected with the surplus of males in various areas (Chen 2004). In a male-dominated society, bride-price is still a symbol of value and dignity for a woman, with a high bride-price representing the high value of the bride, which improves the status of the bride’s family. In Xiajia village in Northern China, for instance, the bride-price has increased 140-fold in the past 50 years, from 200 Chinese yuan in the early 1950s to 28,500 yuan in the late 1990s (Yan 2003). The bride-price has risen 70-fold in the past 30 years in Zhao village in Gansu, and in the late 1990s, it was the equivalent of 20 years’ average per capita income (Sun 2005). To some extent, the bride-price reflects a young woman’s value: today, marriage can entail building a new house, buying expensive household appliances, and so on. These things can cost the groom’s family many years of savings (Jia 2008).

Although women’s bargaining power has improved in the male-squeezed marriage market, the shortage of women may not have enhanced their social status. Discrimination against unborn girls today is a reflection of the low status of women (Attané 2013). A high sex ratio at birth and female child mortality mean that unborn and infant females have been deprived of the right to live due to gender discrimination. This not only violates the constitution and laws of China, but also breaches international covenants on human rights. Men tend to be dominant in the decisions about number and gender of offspring, and women can suffer great psychological distress and sacrifice their health to satisfy men’s preference for a child’s gender. In today’s China, females are at a disadvantage in access to social public resources, which hinders their personal development (Ma 2004).

Another issue raised by the imbalanced sex structure is that women are increasingly likely to be abducted, trafficked and commercialized to compensate for the shortage of potential female spouses, and sold to men who can afford to pay for them (Attané 2013). In some traditional views, a person can be treated as goods to trade, and some Chinese people still hold the opinion that spending money to buy a wife is a “fair deal”. Once women from other places have been trafficked to a village, the villagers sometimes conspire to prevent these women from running away, and even to prevent their rescue (Peng 2004; Sun 2004). Some grass-root cadres regard human traffickers as simple matchmakers and treat the crimes of abduction and sale of women as a necessary evil, offering a solution for villagers who would otherwise be unable to find a spouse (Sun 2004).

The shortage of women may improve women’s bargaining power in some respects, but has not radically transformed people’s perception of gendered roles, nor has it fundamentally enhanced women’s social status. On the contrary, men’s demand for marriage and sex often encourage crimes against women, such as abduction, rape, forced marriage and enslavement (Jin et al. 2012). The shortage of women and their scarcity in the marriage market has not reversed the gender relationship whereby “the status of men is higher than women”, but has further jeopardized the rights and interests of females (Attané 2013).

Notes

- 1.

The sex ratio of potential first marriage partners is defined as the ratio of age-specific male numbers weighted by age-specific first marriage frequencies, to age-specific female numbers weighted by the corresponding first marriage frequencies (Jiang et al. 2011).

- 2.

The age range was restricted to ages 15–60, and it was assumed that the SRB drops to 110 between 2010 and 2030 and then to 106 by 2050. Jiang et al. (2011) then predicted the first marriage ratio in the marriage market from 2010 to 2050, as well as the number and proportion of surplus males.

- 3.

The number of surplus males in the marriage market each single year is obtained by calculating the difference between the number of potential first-marriage males (calculated as the sum of the age-specific male numbers weighted by the corresponding age-specific first-marriage frequencies for males) and of potential first-marriage females for a given year. The proportion is the quotient of the difference divided by the sum of potential first marriage males over the age range.

- 4.

“Bare branches” is an expression that applies to men who, being unable to marry, cannot form a family since, under prevailing social and familial norms, growing new branches on the family tree is impossible without marriage (Attané et al. 2013).

References

Attané, I. (2013). The Demographic masculinization of China. Hoping for a son. Dordrecht: Springer.

Attané, I., Zhang, Q., Li, S., Yang, X., & Guilmoto, C. Z. (2013). Bachelorhood and sexuality in a context of female shortage: Evidence from a survey in rural Anhui, China. The China Quarterly, 215, 1–24.

Barber, N. (2000). The sex ratio as a predictor of cross-national variation in violent crime. Cross-Cultural Research, 34(3), 264–282.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Bélanger, D. (2011). The impact of transnational migration on gender and marriage in sending communities of Vietnam. Current Sociology, 59(1), 59–77.

Chen, Y. (2004). Zhongguo he Ouzhou hunyin shichang toushi (A Look at the Marriage Market in China and Europe). Nanjing: Nanjing University Press.

Chen, Y. (2006). Guanggun jieceng jiuyao chuxian (A class of bare branches is forming). Baike zhishi, 28(5), 52–53.

Chen, X., Yin Y., Tucker, J. D., Xing, G., Chang, F., Wang, T., Wang, H., Huang, P., & Cohen, M. S. (2007). Detection of acute and established HIV Infections in sexually transmitted disease clinics in Guangxi, China. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 196(11), 1654–1661.

Courtwright, D. T. (2001). Violent land, single men and social disorder from the frontier to the inner city. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Das Gupta, M., Chung, W., & Li, S. (2009). Evidence for an incipient decline in numbers of missing girls in China and India. Population and Development Review, 35(2), 401–416.

Dreze, J., & Khera, R. (2000). Crime, gender, and society in India: Insights from homicide data. Population and Development Review, 26(2), 335–352.

Ebenstein, A., & Sharygin, E. J. (2009). The consequences of the “missing girls” of China. The World Bank Economic Review, 23(3), 399–425.

Edlund, L., Li, H., Yi, J., & Zhang, J. (2007). Sex ratios and crime: Evidence from China’s one-child policy. IZA Discussion Paper No 3214.

Guilmoto, C. Z. (2012). Skewed sex ratios at birth and future marriage squeeze in China and India, 2005–2100. Demography, 49(1), 77–100.

He, H. (2007). Guizhou Paifang cun: 282 tiao guanggun de xinlingshi (Paifang village in Guizhou Province: The mental history of 282 bachelors). Xiangzhen luntan, 19(18), 20–23.

Hershatter, G. (1997). Dangerous pleasures: Prostitution and modernity in twentieth-century Shanghai. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hudson, V. M., & Den Boer, A. M. (2004). Bare branches: The security implications of Asia’s surplus male population. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jia, Z. (2008). Renkou liudong beijing xia nongcun qian fada diqu nan qingnian hunyin kunnan wenti fenxi—yi Fenshuiling weili (Young men’s difficulties to marry in a context of migration: a case study of Fenshuiling Village). Qingnian yanjiu, 31(3), 37–42.

Jiang, Q., & Li, S. (2009). Nvxing queshi yu shehui anquan (Female Deficit and Social Stability). Beijing: Social Sciences Press.

Jiang, Q., & Sánchez Barricarte, J. J. (2012). Bride price in China: The obstacle to ‘Bare Branches’ seeking marriage. The History of the Family, 17(1), 2–15.

Jiang, Q., & Sánchez Barricarte, J. J. (2013). Socio-demographic risks and challenges of barebranch villages in China. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 7(2), 99–116.

Jiang Q., Li S., & Feldman, M. W. (2011) Demographic consequences of gender discrimination in China: simulation analysis of policy options. Population Research and Policy Review, 30, 619–638.

Jin, X., Liu, L., Li, Y., Feldman, M.W., & Li, S. (2012). Gender imbalance, involuntary bachelors and community security: Evidence from a survey of hundreds of villages in rural China. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, May 3–5, San Francisco, USA.

Liu, H., Li, S., & Feldman,M. W. (2012). Forced bachelors, migration and HIV transmission risk under China’s gender imbalance: A meta-analysis. Aids Care, 24(12), 1487–1495.

Li, X. H. (2013, March 5). Woguo ying’er xingbiebi silianjiang (China’s sex ratio at birth has been declined for four consecutive years). Renmin ribao.

Li, S., Jiang, Q., & Feldman, M. W. (2006). Xingbie qishi yu renkou fazhan (Gender discrimination and population development). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press.

Li, Y., Li, S., & Peng, Y. (2009). Nongcun daling weihun nanxing yu yi hun nanxing xinli fuli de bijiao yanjiu (A comparison of psychological wellbeing between forced bachelor and married male). Renkou yu fazhan, 15(4), 2–12.

Li, S., Zhang, Q., Yang, X., & Attané, I. (2010). Male singlehood, poverty and sexuality in rural China: An exploratory survey. Population, 65(4), 16–32.

Ma, Y. (2004). Cong xingbie pingdeng de shijiao kan chusheng yinger xingbiebi (The sex ratio at birth from the perspective of gender equality). Renkou yanjiu, 28(5), 75–79.

Mazur, A., & Michalek, J. (1998). Marriage, divorce, and male testosterone. Social Forces, 77(1), 315–330.

Merli, M. G., Hertog, S., Wang, B., & Li, J. (2006). Modelling the spread of HIV/AIDS in China: The role of sexual transmission. Population Studies, 60(1), 1–22.

Mo, L. (2005). Chusheng renkou xingbiebi shenggao de houguo yanjiu (A study of the consequence of the increased sex ratio at birth). Beijing: Chinese Population Press.

NBS. (2000–2009). Quanguo renkou biandong qingkuang chouyang diaocha (Annual surveys on population change). http://www.stats.gov.cn/. Accessed 22 Nov 2013.

PCO. (1985). Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China. Zhongguo 1982 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 1982 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: Zhongguo renkou chubanshe.

PCO. (1993). Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China. Zhongguo 1990 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 1990 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: Zhongguo renkou chubanshe.

PCO. (2002). Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China, Zhongguo 2000 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 2000 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: China Statistics Press.

PCO. (2012). Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China, Zhongguo 2010 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China). Beijing: China Statistics Press.

Peng, Y. (2004). Pinkun diqu daling qingnian hunyin shipei xianxiang tanxi (Marriage mismatch of elder youth in poor areas). Qingnian yanjiu, 22(6), 18–20.

Porter, M. (2009). The effects of sex ratio imbalance in China on marriage and household decision. Working paper, University of Chicago, Department of Economics.

Poston, D. L., Conde, E., & De Salvo, B. (2011). China’s unbalanced sex ratio at birth, millions of excess bachelors and societal implications. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 6(4), 314–320.

Shi, R. (2006). Qingnian renkou qianchu nongcun dui nongcun hunyin de yingxiang (The influence of the emigration of young people on marriage in rural areas). Renkou yanjiu, 28(1), 32–36.

Sun, L. (2004). Dangdai zhongguo guaimai renkou fanzui yanjiu (Study on crimes of human trafficking in contemporary China). Doctoral dissertation, East China University of Political Science and Law.

Sun, S. (2005). Nongmin de ze’ou xingtai—dui xibei Zhaocun de shizheng yanjiu (Forms of mate-selection among farmers: Study on Zhaocun, Northwest China). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Tan, L., Short, S. E., & Liu, H. (2003). Shuangchong wailaizhe de shenghuo—nvxing hunyin yimin de shenghuo jingli fenxi (The life of “double outsiders”: An analysis of the experience of women marriage migrants). Shehuixue yanjiu, 18(2), 75–83.

Tao, T., & Zhang, X. (2013). Liupu renkou shuju de loubao yu chongbao (Underreporting and over-reporting in China’s sixth national population census). Renkou yanjiu, 37(1), 42–53.

Wang, S., Wu, M., & Guo, Z. (2008). Hubei xuan’enxian changtanhe dongzuxiang chenjiataicun weihe guanggun duo (Why there are so many bachelors in Chen Jiatai village, Hubei). Minzu dajiating, 26(1), 20–22.

Wei, S., & Zhang, X. (2011). The competitive saving motive: Evidence from rising sex ratios and savings rates in China. Journal of Political Economy, 119(3), 511–564.

Xu, J., & Liang, X. (2007). Yanbianzhou nongcun daling weihun nan qingnian qingkuang diaocha baogao (Investigation report on the situation of rural unmarried male above the normal age for marriage in Yanbian). Renkou xuekan, 28(4), 63–65.

Yan, Y. (2003). Private life under socialism: Love, intimacy, and family change in a Chinese village, 1949–1999. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Yang, X., Attané, I., Li, S., & Zhang, Q. (2012). On same-sex sexual behaviors among male bachelors in rural China: Evidence from a female shortage context. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(2), 108–119.

Zhang, Q., Attané, I., Li, S., & Yang, X. (2011). Condom use intentions among “forced” male bachelors in rural China: Findings from a field survey conducted in a context of female deficit. Genus, LXVII(1), 21–44.

Zhong, L., & Liu, B. (2006, March 2). Xinjiang qitai wuqian danshenhan pan xifu (Five thousand bachelors hope to have wives in Qitai county, Xinjiang). Zhongguo qingnianbao.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Conclusion

Conclusion

The young cohorts entering the marriage market will be increasingly male-biased, with the result that, until the mid-century at least, millions of men in China will be unable to marry. As demonstrated above, this new demographic concern is liable to have various consequences for society, families and individuals.

In a family-based society like China, men who cannot marry are subject to social discrimination and pressure, and so are their families. A considerable fraction of the Chinese men experiencing involuntary prolonged or even permanent bachelorhood go through life as second-class citizens, as certain prerogatives of what is considered in most societies as an ordinary life are partially or totally inaccessible to them: they are unable to enjoy sexual activity with a regular partner, raise children or share their daily life with a spouse. In many parts of rural China, all of these basic expectations remain the preserve of married men (Attané et al. 2013). Compared to married men, the “bare branches” often have fewer social interactions, have weaker social networks, and more rarely participate in community activities (Jiang and Sánchez Barricarte 2013; Li et al. 2010). They are also exposed to increased risk to their sexual health, as they more frequently have casual partners, including prostitutes, than married men, and seldom use condoms (Yang et al. 2012), and this could accelerate the expansion of the HIV-AIDS epidemic.

As far as can be assessed by available studies, the consequences of the male marriage squeeze will be overwhelmingly negative, with probably only meagre benefits for society and individuals. In response to this trend, major social changes will necessarily occur. Among the positive changes, there may arguably be a loosening of the social and traditional norms governing family arrangements and sexual behaviour in China (Attané et al. 2013). The full range of possible future changes is not yet well defined, however, opening the way for further research.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Li, S., Jiang, Q., Feldman, M. (2014). The Male Surplus in China’s Marriage Market: Review and Prospects. In: Attané, I., Gu, B. (eds) Analysing China's Population. INED Population Studies, vol 3. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8987-5_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8987-5_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-8986-8

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-8987-5

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)