Abstract

Our chapter focuses on the language and literacy development of Israeli Arabic-speaking kindergarten children within the context of their family. We researched two different literacy activities: storybook reading and joint word writing. The chapter presents results of the contribution of these activities, as well as socio-economic status (hereafter, SES) and home literacy environment (hereafter, HLE), to children’s literacy level in kindergarten among Israeli Arabic-speaking families. A total of 109 kindergarten children and their mothers participated in the study. Children’s literacy level was assessed in kindergarten.

Mothers and children were videotaped at home during a book reading activity and in a word writing activity, and demographic and HLE data were gathered from the mothers. Mothers showed low to medium levels of mediation in the bookreading activity by focusing mainly on paraphrasing, and in the writing activity by mainly naming the letters and providing a model for copying. However, while the results from the writing activity followed Bronfenbrenner’s three-layered ecological model (SES, HLE and parental mediation) as expected, reading showed a contribution only from the two first layers, SES and HLE.

We conclude that the linguistic gap between the spoken and the language of literacy, Standard Arabic (or Literary Arabic) poses difficulties and may be confusing for the mothers in mediating the written language across literacy activities, reading and writing. Our study points to the importance of the family’s HLE and SES for children’s early literacy. Future studies should emphasize how to best design family intervention programs so as to maximize children’s literacy growth within the Arabic-speaking family.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Arabic

- Diglossia

- Literacy activities

- Home literacy environment

- Socio-economic status

- Storybook reading

- Joint word writing

1 Introduction

This chapter focuses on the family literacy context in which Israeli Arab kindergarten children live, and its relation to their literacy skills. Literacy acquisition seems to be a singular and interesting process for young Arabic-speaking children, due to the distinctiveness and complexity of this language (Holes 1995) . This assumption is grounded in the socio-linguistic phenomenon of diglossia, and the subsequent linguistic distance that exists between the spoken and the standard written language variety. (For more on diglossia see, in this collection, Khamis-Dakwar & Makhoul, for assessment; Myhill, for a cross-linguistic perspective; Saiegh-Haddad & Spolsky, for ideologies and implications for language instruction; Rosenhouse, for manifestations in textbooks) .

Written texts in all languages differ to some extent from the everyday spoken language. However, Arabic diglossia manifests itself in great differences between the standard language (called "Fusħa" ‘eloquent language’) and the spoken language (called “ʕa:mmiyya” ‘colloquial language’) (Ferguson 1971 [1962]) . (For a discussion of some of the linguistic differences, see in this collection, Laks & Berman and Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb). Unlike Spoken Arabic (hereafter, SpA) which is used for daily communication, Standard Arabic (hereafter, StA) is reserved for formal communication and is studied mainly in school (Meesls 1979; Somah 1980) . While parents in various cultures and languages are reported to serve as facilitators in bridging the orality-literacy gapfor their children, Arab Israeli parents have been reported as seldom exposing their young children to StA (Feitelson et al. 1993) . This may be due to the structural complexity of StA and subsequently parental belief that early exposure to literary Arabic could be a burden for young children (Abu-Rabia 2004) . The reported limited exposure to StA texts might be responsible for the difficulties of Arabic-speaking children in listening comprehension (Feitelson et al. 1993; Ministry of Education 2001) , acquisition of basic reading skills (Eviater and Ibrahim, Chap. 4; Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004; Saiegh-Haddad et al. 2011) and later on in reading comprehension (Abu-Rabia 2000) .

Besides the linguistic distance between the spoken and the written varieties of Arabic, the Arabic orthography itself is also complex (Ibrahim et al. 2002) and consists of a dual system of letters and diacritics. Further, Arabic script is cursive with 22 of the 28 letters having four different shapes depending on their position within the word and on the nature of the preceding letter. Further, many letters share one identical basic shape and are distinguished only by the number and location of dots. This latter characteristic reflects the historical evolution of the Arabic orthographic system. (For a detailed description of Arabic language and orthography, see Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Chap. 1). These orthographic features have been argued to make orthographic processing in Arabic difficult. (For more on the impact of Arabic orthography on letter processing and reading, see Eviatar & Ibrahim, Chap. 4).

The theoretical framework of the research presented in this chapter is socio-cultural and is based on the premise that culture shapes the mind (Rogoff 1990; Vygotsky 1978; Wertsch 1985) . In other words, the individual’s mental activity is external and social, and is internalized by the individual in the course of joint activity with more experienced others. More specifically, the study is grounded in Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) model, according to which various layers of context affect the individual’s development. In his model, Bronfenbrenner refers to macrosystems such as cultural, social, or ethnic groups; mesosystems including close groups such as family or peers; and microsystems, or proximal processes—the actual interactions between children and significant others. In this study, we examined a model of three contextual layers reflecting the three depicted above and their relationship to Arabic-speaking kindergartners’ early literacy : SES, children’s literacy environment at home, and the nature of maternal literacy mediation: storybook reading and joint writing. (For more on environmental factors and literacy development, see Farran, Bingham, & Matthews and Tibi & McLeod, in this collection).

Reading and writing are essential tools in modern cultures, and success in these areas is central to academic achievement and beyond (Cunningham and Stanovich 1998) . The literacy code is a creation of culture and society and is passed from generation to generation (Olson 1984) and parents usually play an important role in this process. Parental mediation , through which children are introduced to this code in their environment, constitutes a central factor in literacy development (Korat 2011; Aram and Levin 2011; McBride-Chang et al. 2010; van Kleeck and Stahl 2003) .

Researchers have reported differences in the quality of maternal mediation in literacy events such as bookreading (Korat et al. 2007; Baker et al. 2001; Heath 1983; Leseman and de Jong 1998; Ninio 1980) and mutual writing (Korat and Levin 2002; Aram and Levin 2011) between families oflow and middle socio-economic statuses (hereafter, SES) , favoring the latter. In the bookreading activity, mothers from low SES (hereafter, LSES) were reported to ask fewer questions and to rarely encourage their children to participate in the event (Ninio 1980) . Moreover, mothers from LSES tend to relate more to illustrations in the book than to language and to paraphrase the text to their children (considered a low level of cognitive mediation), whereas mothers from middle SES (hereafter, MSES) are reported to discuss the story content with their children, to use rich vocabulary and complex language and to relate to the properties of the written text (reflecting a high level of cognitive mediation) (Korat et al. 2007) . In writing, Hebrew-speaking mothers from MSES were found to communicate the steps in the encoding process to their children and to encourage them to carry out those steps during parent-child writing activities. They were also found to give their children more autonomy than mothers from LSES in printing the letters and to refer to the Hebrew orthography more often during joint writing (Aram and Levin 2001) .

Children’s literacy development is not related to parental mediation only but also to more general factors, such as family SES and the home literacy environment (hereafter, HLE). The relation between SES level and children’s achievements in oral language and literacy skills is well documented (Aram and Levin 2001; Korat et al. 2007; Korat and Levin 2002; Walker et al. 1994) . Children from MSES present better language and early literacy skills than children from LSES (Bowey 1995; Lonigan and Whitehurst 1998; Ninio 1980; Raz and Bryant 1990) .There are also reports on the connection between HLE measured by the amount of literary artifacts (books, journals for adults and children, writing materials, etc.) and by the frequency of literacy activities at home (prevalence of reading books to children, visits to the library, etc.) (Heath 1983; Wells 1985) and children’s language and literacy achievements (Evans et al. 2000; Hecht et al. 2000) . A literacy environment that includes many artifacts predicts children’s early literacy in kindergarten (reading, writing, phonological and orthographic awareness) (Aram and Levin 2001; Purcell-Gates 1996; Stuart et al. 1998) . Other studies report that a literacy environment rich in artifacts (e.g., paper, pens, books, newspapers, and computers) contributes to later achievement in reading comprehension (Caretti et al. 2009; Catts 2009; Cunningam 2010; Hirsch 2003) .

It is important to note that a search in the published literature on the relationship between SES, HLE and children’s early literacy did not reveal any such research among Arabic-speaking families. We did not find any published research that documents the nature of parental storybook reading or writing interactions with young Arabic-speaking children. In the present chapter we present a pioneering study addressing variables and the relationships among them. We aimed to learn how family SES, HLE and maternal mediation in a bookreading event and in a collaborative writing activity contribute to Arabic-speaking kindergartners’ language and early literacy . This investigation is highly warranted, given the diglossic context of Arabic on the one hand, and the low literacy achievements of Arabic-speaking children in Israel , on the other (Zuzovsky 2011) .

It should be noted that our research project focused on a large number of families and incorporated two projects aiming at two different activities—book reading and word writing. Data analysis was insured by the specific aims of each project.

1.1 Method

1.1.1 Participants

One hundred and nine 5 to 6-year old children and their mothers took part in this study. The families were from four communities located in the center or north of Israel and represent different types of settlements in which Arabs currently live in Israel: (a) Muslim Arab village in the north, (b) Mixed Christian and Muslim Arab city in the north, (c) Muslim Arab neighborhood in a mixed Jewish and Arab city in the center of Israel and (d) Muslim city in the center of Israel. All children came from homes in which Arabic was the principal language. In the kindergarten , book reading took place once a week, letters were presented on the walls, and the teachers used work sheets for teaching letters once a week . The children at kindergarten were exposed to television programs broadcast in StA, without the teachers’ guidance, 2 to 3 times a week.

1.1.2 Procedure

Data were collected in four sessions. In the first session, the children’s early literacy (hereafter, EL) was assessed individually within their kindergarten setting towards the end of the school year, from May to June. Two individual meetings (between 20–30 min each) were held with each child participating in the study. In the second session, mother-child dyads participated in a joint story bookreading activity in their homes . The mothers were given an unfamiliar storybook and were asked to read it to their children as they deemed fit. This activity was videotaped and later analyzed. In the third session, 3 to 4 days after the bookreading activity, we asked the mothers to help their children write six words. This activity was also videotaped and analyzed. The mothers and their children received six cards, each of which displayed a drawing of an object. The mothers were asked to help their children write the words to the best of their ability, without any further directions. Demographic and HLE information was gathered at home in the fourth session, two to three days later .

1.1.3 Research Instruments

1.1.3.1 Maternal Mediation in Bookreading

We used the children’s book Arrogant Little Rabbit by Abdo Muhammad (no year of publication is provided) in the mother-child bookreading activity. The book was not familiar to the parents or the teachers in the Arabic-speaking communities that participated in our study. The book contains 10 pages, each of which includes 1–2 lines and a matching colorful line drawing of the scene. The narrative includes elements of exposition, problem and solution and tells about an arrogant little rabbit that refuses to play with a turtle, a lamb and another rabbit. One day a fox comes to attack the rabbit and eat it. All the animals that the rabbit refused to play with hurry to help it. The rabbit apologizes to all the animals, thanks them for their kindness and offers to become friends with them.

The mother-child interaction was segmented into verbal units. A verbal unit constitutes the smallest unit. A few verbal units (3 to 5) usually constitute a topic unit. A topic unit was coded only when a new content was added to the previous discourse. Each topic unit was coded into only one of five categories. In the few cases in which a topic unit referred to more than one category, a discussion and decision was made by the two raters as to the category to which it seemed to fit better. This coding system was based on work carried out by Bus et al. (2000) and was modified for the purposes of the current study. Inter-judge reliabilities for segmenting the interaction into content units were computed based on a random selection of 10 % of the dyads. Reliability measured by Cohen’s Kappa was 0.80, p < 0.001.

The topic units were classified into five levels, from low (1) to high (5), as follows: (1) relating to illustrations in the book (e.g., naming characters and objects in the illustrations, referring to the relationship between the text and the illustrations, or naming details in the illustrations that were not mentioned in the story); (2) narrating the story in spoken Arabic (the mother reads the story silently, then tells the story in spoken Arabic); (3) reading and paraphrasing (the mother reads the story aloud, then paraphrases the text—this includes word explanations and sentence completion); (4) promoting text comprehension via “distancing” (e.g., relating to the child’s own relevant experiences to further text comprehension or making connections beyond the text, including instructions, recollection and reconstruction); (5) relating to the written text—the orthography and the decoding/reading process . The hierarchy of the levels was determined by “moving from concrete immediately available information” (De Temple and Snow 1996, p. 54) to higher cognitive or abstraction processes, termed by Sigel (1982) as “distancing”. Each content unit that could be classified into the five categories was given a score ranging from 1 = low (naming of characters and objects) to 5 = high (relating to the orthographic system that appears in the book). Inter-judge reliabilities for sorting content units were computed based on a random selection of 10 % of the dyads. The reliability for maternal mediation levels was K = 0.79.

1.1.3.2 Maternal Mediation in Joint Writing

The mothers helped their children write six mundane words that are part of children’s spoken vocabulary . The mothers and children received six cards, each of which displayed a drawing of an object that is referred to using a different word in SpA and StA. The objects were: glass (StA kaʔs—SpA,كأسkubba:y—/كباي bed (StA sari:r—سرير SpA taxit—;(تخت telephone (StA ha:tif—هاتف, SpAtalifo:n—تلفون shoe (StA ħia:?—حذاء, SpAkundara—كندره bag (StAħaqi:ba—حقيبه SpA shanta—(شنته and cat (StAqi tt a—SpA,قطهbissi—(بسة. The mothers were asked to help their children write the words as best as they could, without any further instruction. Videotapes of the dyadic interactions were transcribed verbatim and the transcripts were used to code the interactions. Two measures were coded: grapho-phonemic mapping and printing mediation.

Grapho-phonemic mediation is the degree to which the mother guides her child through the process of segmenting each word into its sounds and retrieving the required letter for each sound when attempting to represent a word in writing . The encoding of each letter was assessed on a 7-point scale. We demonstrate the scale’s range for the word ‘bed’StA sarir سرير -: (1) The mother refers to the word as a whole: “Write sarir”. (2) The mother utters the sequence of sounds that create the word, for example: “Write sa—ri- r”. (3) The mother refers to each letter separately—dictates a letter name, for example: “Write Sin” [the letter name for S]. (4) The mother retrieves the target phoneme or CV phonological unit and immediately dictates the required letter name, for example: “sa—Sin” [the sound sa and the letter Sin]. (5) The mother retrieves the phonological unit and encourages the child to link it with a letter name , for example: “It starts with sa so which letter is it?” (6) The mother encourages the child to retrieve the phonological unit and link it with a letter name (either Spoken or Standard), for example: “sa-ri-r so what do you hear at the beginning, which letter is it?”; and (7) the mother encourages the child to go through the whole process independently while supporting the child along the way when help is needed. The average scores across the letters yielded the grapho-phonemic mediation score (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient across the letters was α = 0.96).

Printing mediation captures the autonomy allowed or encouraged by the parent in printing each letter. The printing of each letter was assessed on an 8-point scale: (1) the mother writes the letter; (2) the mother writes the letter holding the child’s hand; (3) the mother writes the letter as a sequence of dots for the child to follow; (4) the mother writes the letter for the child to copy ; (5) the mother virtually demonstrates the letter’s shape in the air or on the table; (6) the mother describes the letter’s shape (e.g., “it’s like a square with two dots”); (7) the mother scaffolds the child by using the child’s previous knowledge, for example tells the child in which familiar word the letter appears; and (8) the child writes the letter independently, encouraged and monitored by the mother. The mean score across the letters yielded the printing mediation score (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient across letters was α = 0.97) .

1.1.3.3 Demographic Information

The mothers were asked for demographic information including data about the present SES of the family. The children’s age (in months) was M = 68.74, SD = 4.99, their mothers’ mean age (years) was M = 30.80, SD = 3.54, and their fathers’ mean age was M = 32.30, SD = 4.24. The families have M = 3.6, SD = 1.47 children, with M = 5.65, SD = 1.46 people living in M = 4.03, SD = 1.18 rooms.

A seven-factor index was used to calculate the families’ SES levels and took the educational and occupational levels of the fathers and mothers, including the family income level into account. The mean of the SES variable was 2.80 (SD = 1.17) (range 1–5; α = .92). The data showed that the mothers’ educational level is higher than that of the fathers (t (108) = 2.17, p < .05), whereas the fathers’ occupational level is higher than that of the mothers (t (108) = 5.08, p < .001). The mean income level of the families (M = 2.58, SD = 1.27) was found to be below the reported average of the Israeli Jewish population (M = 3.19, SD = .90, see Gallili 2006) and is similar to that of the Jewishlow SES population (M = 2.76, SD = .92).

1.1.3.4 Home Literacy Environment

The mothers were asked to give information about the Home Literacy Environment(HLE) of their families. The questionnaire included aspects such as the number of adult and children’s books in the home, frequency of parental reading of books to the child , newspaper subscription (children and adults), number of videos and DVDs, mother’s reading pleasure, and the number of children’s educational games in the home (α = 0.76). According our findings, Arab families’ homes in our sample had on average one computer, very few educational games for reading (M = 6.09, SD = 5.46) and arithmetic (M = 3.56, SD = 4.04), some computer games (M = 6. 90, SD = 0.63), and video cassettes and DVDs (M = 14.11, SD = 12.95). We counted (on average) only 30 children’s books and 29 adult books in these homes. About one third of the families reported that they had a subscription to an adult newspaper. The mothers reported reading to their children on average every three days (about 11 days a month), while fathers’ reading to their children was reportedly only once a month. The average age of beginning reading to children was reported as one year and 6 months. Most variables, including the existence of literacy tools: computers (r = 0.34, p < 0.001), computer games (r = 0.28, p < 0.001), videos, DVDs (r = 0.58, p < 0.001), educational games in arithmetic (r = .44, p < 0.001)and reading (r = 0.30, p < 0.001)were correlated positively and significantly with the families’ SES. Reading frequency to the child as reported by the mother was not found to correlate with the family’s SES .

1.1.3.5 Children’s Emergent Literacy Level

The children’s emergent literacy (EL) level was assessed using two categories: written language and spoken language skills. Written language included nine parameters: letter knowledge (letter names, letter-sound knowledge and letter writing ability), concept of print, phonological awareness , orthographic awareness, literary word writing and word recognition. Spoken language ability included six parameters: expressive vocabulary knowledge of onsite words (Spoken and Standard Arabic), receptive knowledge, and listening comprehension of written sentences and a story.

1.1.3.6 Written Language Tasks

Letter naming

The children were presented with 29 letters (including final non-connected letter shapes) of the Arabic script . Each letter was written on a card. With the card facing down, the child was asked to randomly pick a letter and say its name . This was repeated 14 times, such that 14 letters were picked. The scale was: 0 = incorrect, 1 = using the letter name used in SpA (إب) 2 = correct, StA letter name .(باء) The reliability coefficient of this tool was α = 0.90.

Letter sound knowledge

The cards used for letter names were given to the children following the same procedure, except that this time they were asked to say the letter sound. The scale range for this task was: 0 = incorrect, 1 = the child said the letter sound embedded within a CV phonological unit (e.g., for the letter N ( ن ) the child said na), 2 = correct, providing only the phoneme that the letter represents; α = 0.93.

Letter writing

The researcher randomly chose 14 letters. She named each letter and asked the child to write it on a card. The researcher used the first letter from the child children were presented s name for an example with feedback. The children’s responses were scored on a 3-point scale: (0) wrong—no answer or wrong answer; (1) partial answer—writing a letter that is similar in shape (e.g., for the letter "ب" (B) writing ث , ن ت, (see, Abu-Rabia and Taha 2006) ; (2) correct answer. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient across the letters was α = 0.90.

Print concepts

An adaptation of Shatil’s Hebrew Concept Abut Print (CAP) test (2001), following Clay (1979, 1989) , was developed and used for Arabic . The children were presented with the book A Surprise for Yara and were asked to answer 16 questions about it. The questions were about concepts such as page, lines, print, drawing including text handling (e.g., where one begins and ends reading a book) and directionality (in Arabic from right to left). Answers were scored as incorrect(or “I don’t know”) (= 0) or correct (= 1) and the range of scores was from 0 to 16, α = 0.84.In all the research tests, “I don’t know” answers were followed by the researcher’s encouragements to the child to make an effort and give an answer .

Phonological awareness

Two phonological awareness tests were developed for the study and administered on two separate days: initial and final phoneme isolation. Each task included 17 one syllable words, all of which were nouns familiar to children. The researcher said each word out loud, and then asked the child to say the initial or final phoneme in each word. The scale range for phonological awareness was: 0 = incorrect; 1 = partially correct—the child said the initial/final phoneme within a CV unit (for rationale and evidential basis, see Saiegh-Haddad 2007) ; 2 = correct phoneme. The alpha reliability coefficient was.96 for the initial phoneme and.97 for the final phoneme isolation task. The mean score across the two tasks served as the phonological awareness score (α = 0.84).

Orthographic Awareness

The Arabic script contains 28 letters, with, as mentioned before, 3–4 different forms each: beginning of the word connected to the left only; beginning of the word (- بـb), connected to the left and to the right; middle of the word (ـبـ- b), connected to the right only (ـب- b);and not connected (ب- b). The children were presented with 16 pairs of StA word stimuli. Each pair consisted of a StA word on one card and a string of signs that do not represent the StA script on another card. The signs comprised letters and numerals in Arabic , Hebrew and English, signs repeated several times resulting in excessively long strings, or wrongly connected words. The researcher presented the two cards to the child and asked her or him to choose the card that represents an Arabic word. Incorrect or “I don’t know” answers were scored = 0 and correct answers were scored = 1. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was 0.82.

Word recognition

This test aimed to examine the children’s ability to recognize StA words. We used three pairs of words, which were familiar to the children: elephant-turtle (سلحفاة – فيلfi:l – sulħafa:h; FYL-SLĦFAḦ); bear-butterfly (,فراشة – دبdub- fara:Šah, DB- FRAŠḦ); giraffe-ox (/ثور – زرافةzara:fah-θawr, ZRAFḦ-θWR). These words were chosen because they represented about half of the Arabic letters and include long vowels, represented in Arabic orthography through compulsory letters, and short vowels, represented through a system of optional diacritics. (For more on the structure of Arabic orthography, see Saiegh-Haddad & Henkin-Roitfarb, Chap. 1) . Furthermore, two cards presented a pair of words where the longer sounding word denoted a smaller referent (e.g., elephant-turtle (سلحفاة – فيل fi:l – sulħafa:h; FYL-SLĦFAḦ) and one pair presented a pair of words where the two referents were similar in their size but one word was longer phonologically and orthographically than the other (giraffe- ox (/ثور – زرافةzara:fah-θawr, ZRAFḦ- θWR). The rationale for including this contrast is found in the literature indicating that before they become aware of the alphabetic principle, young children tend to use a referential strategy where more letters are used for bigger referents (Levin and Korat 1993) . Each word was written on a separate card and its matching drawing appeared on another card. The researcher put the two cards with the two words and the two cards with the matching drawings in front of the child and said, for example : “Here are two pictures for a butterfly and a bear, and also two cards for the two words ‘butterfly’ and ‘bear’. Please put the word ‘butterfly’ under the picture of the butterfly and the word ‘bear’ under the picture of the bear.” The scale for this task was: incorrect or “I don’t know” = 0 or correct = 1, α = 0.62. After giving their answer, the children were asked to explain their judgments. The children’s reasoning was classified into five levels, from low (1) to high (5) (Levin and Korat 1993) , as follows: 1 = egocentric argument, 2 = semantic argument, 3 = phonological argument, 4 = argument based on letters, 5 = argument based on reading (the child read the word). Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.91 .

Word writing

The children were asked to write the same words used in the word recognition task (described above). The words were different from the words the children had been asked to write at home with the help of their mothers. Three cards displaying drawings of two nouns were presented randomly, with a blank card for writing each pair’s names. The oral instructions for each card were, for example: “Write the word ‘turtle’ and then the word ‘elephant’”. Each word was scored on a 10-point scale adapted from Levin, Share, and Shatil (1996) , ranging from pseudo letters through random letters, basic consonantal spellings, partial consonantal spellings, to formal writing. Higher scores indicated a higher, more formal level of writing. The mean score across the eight words served as the word writing score. Cronbach’s reliability coefficient across words was α = 0.97.

1.1.3.7 Spoken Language Tasks

Expressive Vocabulary

We used the antonyms sub-test from Kaufman’s Battery for Children (K-ABC) (1983) test in order to assess the children’s vocabulary in SpA and StA. This test assesses the children’s productive vocabulary by asking them to provide the opposite word to the word presented to them. Eighteen words from the K-ABC were translated into Arabic to test productive vocabulary (antonyms) for each test (a) in SpA and (b) in StA . The test was administered on two days. On the first day the researcher said the word in SpA and asked the child to give the opposite of this word . On the second day, the experimenter said the word in StA and asked the child to say the opposite of this word. The scale range was 0 = incorrect, 1 = correct. Cronbach’s reliability coefficient across words was (α = 0.85) for literary Arabic words and (α = 0.89) for spoken Arabic words .

Receptive vocabulary (an adapted translation of PPVT—Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test)

The children’s vocabulary was evaluated using an adapted translation of the PPVT test (Dunn and Dunn 1981) . This test measures receptive vocabulary knowledge of children aged 2 to adulthood. Adaptation to Arabic following the Hebrew version (Nevo and Oren 1979) was performed by a group of Arab researchers, educators, and linguists and used both SpA and StA words. Based on a preliminary pilot, we used the first 40 items. In each item the child was shown 4 pictures and was asked to indicate the drawing that matched the word said by the researcher. The scale range was 0 = incorrect, 1 = correct. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.85.

Story comprehension

A translation of the story Kamil and Lassie Dog (Shatil 2001) from Hebrew into Arabic was used for this test. After the researcher read the story twice to the children, she presented them with 12 true/false questions about the story. The scale range was 0 = correct, 1 = incorrect. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.65.

Sentence comprehension

Shatil and Nevos’ sentence comprehension test (2007) was translated from Hebrew into Arabic in order to evaluate the children’s sentence comprehension. The children were asked to indicate which of the drawings best matched the sentence read to them by the researcher (e.g., the researcher said: “My mother said: take the book and bring it to the library". Which of the pictures that you see here (out of four) represents this sentence?).The distractors were syntactic manipulations of the target sentence. The scale was incorrect (or “I don’t know”) = 0, correct = 1. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.70.

1.2 Results

1.2.1 Children’s Emergent Literacy

The mean and SD of the children’s literacy level in kindergarten in Spoken and Standard Arabic and correlations with SES and HLE are presented in Table 15.1. Children’s scores are presented as percentage .

According to Table 15.1, Arabic-speaking kindergarten children present a low level of literacy skills across most variables and large standard deviations that demonstrate great diversity among them. The children’s knowledge of the concept about print (M = 68.63, SD = 23.78) was the highest among the written skills tested, whereas letter-sound knowledge (M = 33.20, SD = 33.00) was the lowest. This in part reflects the children’s frequent use of the spoken letter names rather than the Standard Arabic letter names, and also difficulties in retrieving the letter sound, especially in the case of some letters such as those representing stop phonemes (plosives) or diglossic phonemes which do not exist in the children’s spoken vernacular (Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2007) . When they succeeded in this task, they usually retrieved a syllable/sub-syllabic unit (CV) and not a phoneme. We are aware that, in some cases, as in the case of stops, it is impossible to retrieve the sound without a following vowel, a CV, while in other cases, as in the case of fricatives, this is possible. This distinction is recommended in future research in order to elucidate this process. In addition, using the spoken names of letters might sometimes imply knowledge of the sound; children might resort to SpA names because they cannot articulate the individual sound. With reference to letter writing, the children seemed to be familiar with the general appearance of most of the letters. The mean score on word writing(M = 37.60, SD = 23.74) appears to be quite low and reflects the children’s frequent use of random letters and basic consonantal representations (using one correct letter from the word accompanied by random letters) when trying to write a word.

The mean score in word recognition(M = 44.72, SD = 32.49) was somewhat higher than letter writing, but was nonetheless low, and showed that when trying to explain their recognition of words, the children tended to use semantic explanations which referred to the object’s features (e.g., “because the turtle is small”), or phonological arguments which referred to the phonological length of words (e.g., “because ox is a short word”).

The children in our sample exhibited some knowledge about print and on average correctly answered 2/3 of the 16 questions that were asked in the CAP test. In phonological awareness , the children succeeded significantly better in retrieving the first phoneme of the word (M = 52.63, SD = 32.06) than the last one (M = 41.28, SD = 39.50) (t = 14.77, p = .000). While this contradicts earlier findings (Saiegh-Haddad 2003, 2004, 2007) , such contradiction may be attributed to the fact that the current scoring rubric gave credit to CV responses.

As to their spoken language, the children scored very low on the expressive vocabulary test in both its SpA and StA versions. On average, they correctly drew the opposites of only 10 % and 23 % of the 18 words in StA and SpA, respectively. In contradistinction, low SES Hebrew-speaking children showed a success rate of M = 47 % in this task (Levin and Aram 2012) . However, the variance on these measures was large. Some children did not know even one word while others correctly wrote 80–90 % of the words. The children performed better on the receptive vocabulary (M = 61.76 %) than on the expressive SpA vocabulary (M = 24.70 %) (t = 21.30; p < 0.001) and expressive StA vocabulary (M = 10.87) (t = 30.13; p < 0.001). Children’s expressive SpA vocabulary was significantly higher than their expressive StA vocabulary (t = 7.88; p < 0.001). Most measures of children’s literacy were positively and significantly correlated with SES (except listening comprehension—sentences and story) and HLE (except PPVT and listening comprehension of sentences) .

1.2.2 Maternal Mediation in Bookreading

An analysis of maternal mediation in the bookreading activity showed that the most prevailing maternal mediation behavior was reading the written text from the book and afterwards paraphrasing it in the spoken language (M = 65.75 %, SD = 22.30). This behavior was followed by story discussion which was remarkably less frequent (M = 22.37 %, SD = 14.90). All other mediation behaviors related to reference to the illustrations (M = 8.11 %, SD = 12.10), or narrating the story in spoken language—without any oral reading of the story in StA (M = 3.06 %, SD = 12.10), as well as relating to the orthographic representation of words (M = 0.70 %, SD = 2.47) which appeared to a much lesser extent.

1.2.3 SES, HLE and Bookreading Mediation as Predicting Children’s literacy

We created one score for all SpA language measures (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.89) and one score for all StA language measures (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.72). The general mean score of literacy level (spoken and written language) was M = 51, SD = 17.00 (Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this test was α = 0.87). The results showed that SES was positively and significantly correlated with HLE (r = 0.60, p < 0.001) and with the children’s general literacy level (r = 0.48. p < 0.001). Furthermore, HLE was correlated with the children’s general literacy level (r = 0.54. p < 0.001). No significant correlations were found between any of the variables tested and maternal bookreading mediation behavior except one. Interestingly, the maternal behavior of relating to the orthographic representation of words was the only one that correlated significantly with SES (r = 0.26, p < 0.1). Higher SES mothers tended to relate to the orthographic representation of words in the book while reading to the child and also had children with higher literacy skills .

Given the overall moderately high correlation between SES and HLE levels, which might indicate a multi-colinearity effect of these two variables, we executed a step-wise regression analysis entering SES as the first predictor , HLE as the second, and maternal mediation as the third, in order to test their possible contribution to the variance in the children’s general literacy score as well as in the written Arabic score and the spoken language score . Regarding the general score, the data show that SES entered in the first step accounted for 19 % of the variance, while HLE entered in the second step accounted for 39 % of the variance, adding 20 % unique variance above SES. Regarding the written language skills, SES contributed 27 % to this score and HLE contributed another unique 8 %. Regarding the spoken language skills, SES contributed 5 % in the first step, and HLE contributed an additional 6 %. Maternal mediation level made no significant contribution to any of the dependent scores tested beyond SES and HLE .

1.2.4 Maternal Mediation in Joint Writing

First we checked what linguistic version of the word (the spoken or the Standard) the mothers chose to use when they mediated word writing to their children. We found that when engaged in the task of word writing, the mothers opted more for the StA form of the word than for the SpA form. About 70 % of the written outcomes were in StA. However, surprisingly, and despite the fact that Spoken Arabic is used only for oral conversation and not for writing in Arabic, 30 % of the writing that mothers asked their children to attempt was in Spoken Arabic. For example, 19 % of the mothers helped their children write the SpA form of the word word بسةinstead of the StA wordقطه when shown a picture of a ‘cat’, 33 % chose the SpA word تختfor ‘bed’ instead of the StA word سريرand 31 % wrote down the SpA word شنطه for ‘bag’ instead of the conventional StA word حقيبه. This might reflect lack of knowledge about the word’s linguistic affiliation, or an attempt on the part of the mother to make the writing activity more meaningful to the child by using the version of the word that the child is familiar with .

Next, in order to study the mothers’ general Arabic-writing mediation strategies, we analyzed the frequency of maternal use of each writing mediation category. The words that the mothers were asked to write with their children included in all a maximum of 26 letters (in StA or SpA). We scored the mediation of each letter separately, since mothers sometimes used different strategies for different letters in mediating one word. In general, the mothers were found to refer to words as wholes (21 %) or as sequences of sounds (26 %). The most frequent strategy used by mothers was dictation of letters (33 %). The mothers seldom connected between sounds and letters (5 %), isolated a sound and encouraged their children to connect it to a letter (5 %), encouraged their children to isolate a sound and connect it to a letter (6 %) or monitored their children during the grapho-phonemic process (5 %). With reference to the level of autonomy that the mothers allowed their children in the print mediation of the letters, we found that they frequently wrote the letters for their children and asked them to just copy (56 %). It is noteworthy that the large standard deviations across all measures reveal the diversity among the mothers and their attitudes toward a joint writing activity with their children.

SES, HLE and joint writing mediation as predicting children’s written language

There is evidence that writing mediation is related to children’s written language skills but not to their general language ability or listening comprehension (e.g., Aram and Levin 2002; Aram et al. 2006) . In the present chapter we focused on the relations between mothers’ writing mediation and a variety of early written skills that we targeted: letter knowledge (letter naming, letter sound knowledge and letter writing), word writing, word recognition, phonological awareness (initial and final phoneme isolation), concept about print and orthographic awareness. The mean score of initial and final phoneme isolation tasks served as the phonological awareness score (α = 0.97) and the mean score across the three letter measures served as the letter knowledge score (α = 0.85).

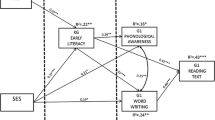

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted in order to examine the unique link between each of the socio-cultural layers targeted (SES and HLE) to the children’s literacy skills, and assess the contribution of maternal writing mediation (grapho-phonemic mediation and printing mediation) to children’s early literacy beyond the effects of SES and HLE. The mean score between maternal grapho-phonemic and printing mediation served as the writing mediation score (α = 0.95). Six separate 3-step fixed-order hierarchical regressions were conducted with SES in the first step, HLE in the second and maternal writing mediation measure entered in the third step (see Table 15.2). The criterion variables were each of the six early literacy measures .

SES (step 1) contributed significant amounts of variance to all early literacy measures : letter knowledge (15 %) , word writing (10 %), word recognition (25 %), concept about print (CAP) (20 %), phonological awareness (21 %) and orthographic awareness (21 %). After partialling out SES, the availability of literacy artifacts at home (HLE) (step 2) added significant amounts of variance to word recognition (4 %), concept about print (4 %), and phonological awareness (4 %). After partialling out SES and HLE, maternal writing mediation (step 3) added significant amounts of variance to letter knowledge (29 %), word writing (18 %), word recognition (11 %), concept about print (15 %) and phonological awareness (11 %).

At the third step, maternal writing mediation made a significant contribution to all early literacy measures (except orthographic awareness). Together, the three socio-cultural layers that were assessed in the present study explain a considerable amount of the variance. SES, HLE and maternal writing mediation explained 46 % of the variance in letter knowledge skills, 29 % in word writing, 39 % in word recognition,40 % in concept about print, 37 % in phonological awareness and 23 % of the variance in orthographic awareness. Overall, SES, HLE and maternal writing mediation explained between 23 % and 46 % of the differences in the children’s early literacy.

1.2.5 Discussion

This pioneering study on the literacy context and mediation in the Arabic-speaking family presents important results on the literacy environment in which Israeli Arabic-speaking children grow up and its relation to children’s early literacy development. It is clear that although our sample included different families living in different areas and a variety of geographical and cultural settings, they all turned out to be low-income families and their SES profile was similar to that of low SES families in the Israeli Jewish Hebrew-speaking population. We found that the Arabic-speaking children in these communities live in an environment that is impoverished in literacy artifacts and activities . Their homes have on average one computer, very few educational games for reading and arithmetic, some computer games, video cassettes and DVDs. We counted an average of 30 children’s books and 29 adult books in these homes.

As reported in previous studies which focused on Hebrew-speaking children (Korat et al. 2007) , the availability of literacy artifacts and the age of starting to read to the child is correlated positively and significantly with the SES of the families . However, in this study, no correlation was found between the reported frequency of book reading to the children and SES. Mothers reported reading to their children on average every three days and reported on fathers’ reading to the children once a month. A possible explanation for this lack of correlation with SES could be an increasing awareness on the part of parents of the importance of the bookreading activity to young children’s literacy development following promotion of this topic by the education system and the media (Bus et al. 1995; Badsh-Landow 2006) . An alternative explanation is social desirability regarding parental report on the frequency of reading across all social groups. An indirect measure for parental bookreading to their children, such as the “Title Recognition Test” (TRT) (Stanovich and West 1989; see also Sénéchal et al. 1998( may have been a more valid and reliable measure of book reading. It is also possible that Arabic-speaking parents read relatively less frequently to their children, regardless of SES (compared to Israeli Hebrew-speaking parents who report reading to their children 2–3 times a week, see Korat et al. 2007) because of the diglossic context. It is recommended to test this assumption in future research.

The study also revealed low (out of the maximum grade for each measure) and highly varied knowledge of both the spoken and the written language skills among children. The general low SES level of the participants and the correlations with HLE and with the children’s literacy appear to go hand in hand (Korat et al. 2003) .

1.2.6 Bookreading Activity

Three important findings are related to the bookreading activity. First, mothers mainly used the behavior of reading the text aloud to the child and then paraphrasing it to him or her . Second, the only behavior that correlated significantly with SES was discussing the writing orthography in the book. Third, the best contributor to children’s literacy level was HLE, followed by SES. One might ask why Arabic-speaking mothers tend to read the text to the children and then paraphrase it to them during most of the reading event (65 % of their behavior) and why they discuss the story (which involves higher cognitive processing ) to a much lesser extent (22 %). Israeli Jewish low SES Hebrew-speaking mothers (Korat et al. 2007) exhibit paraphrasing in only 32 % of their behavior, and in the middle SES this happens in only 22 % of the cases. Discussion beyond the text appeared in 41 % of the behavior of Israeli Jewish low SES Hebrew-speaking mothers and in 50 % of the middle SES. The behavior of the Arabic-speaking mothers may be related to the diglossic nature of the Arabic language. Since their children are not familiar with the written language, StA (as this language is not acquired naturally but is rather limited to literacy related activities and to some TV programs and religious sermons), mothers mediate the written text to their children by telling the story in SpA, the everyday familiar language. They might feel that in this manner they are bypassing the language’s obstacles to story comprehension: unknown words (lexicon) , different morphology and syntax . Arabic-speaking mothers work mainly on the linguistic "translation" of the book to their young children and leave much less time for higher cognitive and abstract discussion of content that goes beyond the text (22 %).

In line with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, we view development as embedded in the socio-cultural context. When studying the impact of reading mediation, we elaborated a model of three contextual layers related to kindergartners’ early literacy : SES, HLE , and the quality of maternal mediation. According to this model, our findings show that the contribution of HLE to children’s literacy level is more significant than SES and goes beyond the family’s SES. Such a relationship between HLE and children’s EL levels converges with previous findings from other languages: Hebrew (Korat et al. 2007) and English (Burgess et al. 2002; Sonnenschien and Munsterman 2002) . Our study expands on the existing database by showing that the same relations exist within the Israeli Arabic-speaking family. The findings may have a positive implication, since although most Arabic-speaking families have a low SES level, HLE and the availability of literacy artifacts and activities within this generally poor society makes a more significant contribution to the children’s literacy level than parental education, profession or income. Thus, literacy material and activities with young children in the Arabic-speaking society in Israel impacts the children’s Spoken and Standard language knowledge before formal learning to read and write at school begins.

However, our findings did not show a significant contribution of maternal mediation in bookreading to the child’s literacy level, as expected by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model. Mothers’ mdiation mostly took the form of paraphrasing, making no contribution to the children’s language and literacy knowledge in kindergarten . We assume that a greater contribution to the children’s literacy level might have been found had mothers used more discussion beyond the text, expanding story comprehension by focusing on integration of different parts of the text and relating the story meaning to the children’s life, including print-related and written language orthographic discussions.

1.2.7 Joint writing Interaction

All children in our study failed to spell all of the dictated words autonomously. As in the case of studies in Hebrew (Aram and Levin 2001) and English (DeBaryshe et al. 1996) , all the mothers in our study helped their children produce readable spellings. Interestingly, in spite of the fact that there is no conventional way of representing Spoken Arabic in writing, and even though this variety is used for oral speech only, about 31 % of the mothers chose to help their children write the words in Spoken Arabic. There is informal evidence from observations in kindergartens and homes of young children that teachers and parents expose children to the standard and spoken forms of the letter names (Levin et al. 2008) . Moreover, our conversations with teachers and parents reveal that they are not sure whether they should write with their young children in Standard Arabic or whether it is better to use the words that the children use in everyday life and write the phonological form of the words as they sound in Spoken Arabic. Some of them told us in private talks that when they write with the children it may be better to focus on the grapho-phonemic process and the printing of the letters and skip the differences between the Spoken and the Standard Arabic vocabulary.

Writing involves several steps: segmentation of the word into phonological units, retrieval of the required letter names and sounds, recruiting the letter shapes, and printing the letters (Treiman 1993) . Mothers must become aware of these steps in order to scaffold writing. Many mothers in our sample did not know how to help their children segment the word into its sounds and treated the word as a whole or as a sequence of sounds (levels 1 and 2 in the grapho-phonemic mediation scale). When it came to printing the words, they felt more competent. However, they did not ask their children to write. Neither did they write for them. They gave the children a model to copy.

Low level mediation, such as merely providing a model for copying a word, may stem from limited awareness and knowledge of the encoding process. Alternatively, mothers may be unaware of their children’s writing level and therefore underestimate their children’s actual level of development. Children’s writing level varied, yet mothers in our study tended to scaffold on a low level. In line with Vygotsky’s (1978) development model, adults should scaffold their children within their Zone of Proximal Development, beyond their actual level, pulling them toward their potential development level in order to support the children’s development. We conceive mother-child interactions as a two-way street where both parties shape the interaction mutually and interactively. However, the mother, as the expert, has the leading role (Vygotsky 1978) . Her interaction style is molded by her previous experiences with her children, but just as much by cultural beliefs and norms of behavior related to parenting (Lightfoot and Valsiner 1992) .

We claim that a significant maternal role comprises an ongoing phenomenon affecting the trajectory of child literacy development . Mothers who mediate literacy at a higher level, from the child’s early age onward, learn about the child’s competencies and use this knowledge to shape their future interactions. Consistently high quality mediation is likely to promote children’s literacy. This may be a central explanation for the substantial contribution of mediation quality to the prediction of children’s literacy levels (e.g., Aram and Levin 2004) .

In line with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, we expected that all the layers in the children’s environment would contribute to their literacy development (see Farran, Bingham, and Matthews, Chap. 16). Nevertheless, we expected that the layer closest to the child (maternal writing mediation) would contribute to the child’s early literacy beyond the contribution of HLE and SES , an expectation that was largely supported. SES, the furthest layer, is related to the child’s general life context . It contributed in the first step of the regression to all of the early literacy measures . The home literacy environment represents a layer closer to the child. It reflects the materials that are present in the child’s environment, the tools with which the child can play and learn literacy. HLE added a significant amount of variance to word recognition, concept about print and phonological awareness beyond the contribution of SES. Maternal writing mediation, the layer closest to the child, that represents the nature of the actual writing interactions between the mother and the child predicted the child’s early literacy beyond SES and HLE .

There is a body of research that connects parent-child literacy interactions to early literacy and acknowledges the importance of these experiences to children’s literacy development (e.g., Wasik and Herrmann 2004) . The results of the present study show that writing interactions comprise contexts where parents can teach their children about the Arabic written system . It seems that Arabic-speaking mothers of young children are frequently confused and ambivalent about the way to mediate writing. We inspire educators of young Arabic-speaking children to encourage parents to write with their children and help the parents learn appropriate ways to mediate writing according their children’s ability and understanding. Mothers can learn to mediate writing on a higher level. Levin and Aram (2011) showed, in an intervention study, that mothers’ writing mediation can be enhanced via direct coaching and that promoting mothers’ writing mediation increased their children’s early literacy .

The results of the present study are consistent with previous studies among children from different countries, in showing a significant relationship between maternal mediation and children’s literacy skills (e.g., Aram 2007; Worzalla et al. 2009) . At the same time, the study reveals some unique aspects of the socio-cultural context in which Arabic literacy development is embedded and the effect of that on mothers’ behavior and their children’s development.

2 Conclusion

In the present study, the mothers showed medium to low levels of mediation by focusing mainly on paraphrasing in the bookreading activity, and by mainly naming the letters and providing a model for copying in the writing activity. However, while the writing activity followed Bronfenbrenner’s three-layered ecological model (SES, HLE and parental mediation) as expected, the reading activity showed a contribution only of the two first layers, SES and HLE . This might be explained by the more direct relationship between the writing activity and the children’s literacy measures than between bookreading activity and literacy development. The nature of the mother-child word writing activity was directly related to the alphabetic tasks given to the children in their individual test. To mediate word writing the mother helped her child in phonological awareness , letter naming and letter-sound connection, and indeed these alphabetic skills are highly related to word writing mediation. In the story-reading activity, which is more complex, we did not assess the children’s vocabulary from the story that their mothers read/narrated to them or their comprehension of the story. If the vocabulary of the book that the mothers read to their children had been used to assess vocabulary knowledge, we might have found that story bookreading makes a significant contribution to children’s vocabulary beyond SES and HLE .

In general, it seems that diglossia, and specifically the linguistic gap between the spoken and the literary language poses difficulties and may be confusing for the mothers in mediating the written language across literacy activities, reading and writing. We view this research as a first step in learning how this context in the Arabic-speaking family is related to children’s literacy development. In order to learn more about parental behavior, a study of Arabic-speaking parents’ beliefs and attitudes regarding diglossia is warranted. Research is also needed into the effect of such beliefs and attitudes on language practice in the Arabic-speaking home and on the literacy exposure, training, and mediation.

It should be noted that the design of this study precludes inferences about causality regarding the relationships between the variables in question. That said, intervention studies are needed in order to learn more about these relationships . For example, Levin and Aram (2011) showed that enhancing maternal writing mediation (in Hebrew) promotes a wide variety of children’s alphabetic skills. To the best of our knowledge, such an intervention program has not yet been conducted in Arabic . Second, including maternal reports on the extent to which they engage their children in print activities, such as teaching their children to print letters or words, could afford greater insight into the home literacy activities and might better explain children’s measured literacy levels (Sénéchal et al. 1998) . Third, the maternal mediation levels which emerged in the current research were based on a single observation of mothers reading a storybook to their children or writing with them. Data based on multiple observations could provide stronger evidence of typical parental mediation levels .

Our pedagogical implications point to the importance of the family’s HLE and SES for the children’s EL level. (For more on environmental factors and literacy development, see Farran, Bingham, & Matthews and Tibi & McLeod, in this collection). Future studies should emphasize how to best design family intervention programs so as to maximize children’s literacy growth . Considering the lack of contribution of maternal mediation in bookreading to children’s EL in the Arabic-speaking community, and the clear contribution of it to the writing activity, we suggest that future intervention efforts incorporate different parental meditational supports in different literacy activities. This might include discussion beyond the text, integrating different parts of the text to elaborate story compression as well as using alphabetic and rhyming intervention programs to encourage discussion of the orthography and aspects of the written register.

References

Abu-Rabia, S. (2000). Effects of exposure to literary Arabic on reading comprehension in a diglossic situation. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 13, 147–157.

Abu-Rabia, S. (2004). Effects of exposure to literary Arabic on reading comprehension in a diglossic situation. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 13, 147–157.

Abu-Rabia, S., & Taha, H. (2006). Reading in Arabic orthography: Characteristics, research findings, and assessment. In P. G. Aaron & M. Joshi (Eds.), Handbook of orthograpy and literacy (pp. 321–338). Mahawh: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Aram, D. (2007). Maternal writing mediation to kindergartners: Analysis via a twins study. Early Education and Development, 18, 71–92.

Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2001). Mother-child joint writing in low SES: Socio-cultural factors, maternal mediation, and early literacy. Cognitive Development, 16, 831–852.

Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2002). Mother-child joint writing and storybook reading: Relations with literacy among low SES kindergartners. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 48, 202–224.

Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2004). The role of maternal mediation of writing to kindergartners in promoting literacy in school: A longitudinal perspective. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 17, 387–409.

Aram, D., & Levin, I. (2011). Home support of children in the writing process: Contributions to early literacy. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of Early Literacy (Vol. 3), (pp. 189–199). NY: Guilford Press.

Aram, D., Most, T., & Mayafit, H. (2006). Contributions of mother-child storybook telling and joint writing to literacy development in kindergartners with hearing loss. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(3), 209–223.

Badsh-Landow, I. (2006). Maternal cognitiveand emotionalmediationin book reading activity and in looking atphoto album: A comparison between two social groups. Thesis submitted to MA degree. School of Education, Bar-Ilan University.

Baker, L., Mackler, K., Sonnenschein, S., & Serpell, R. (2001). Parentʼinteractions with their first-grade children during storybook reading and relations with subsequent home reading activity and reading achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 415–438.

Bowey, J. (1995). Socioeconomic status differences in pre-school phonological sensitivity and first-grade reading achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87, 476–487.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979).The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bus, A. G., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Pellegrini, A. D. (1995). Story book reading makes for success in learning to read. A meta-analysis on the intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of Educational Research, 65, 1–21.

Bus, A. G., Leseman, P. P., & Keultjes, P. (2000). Joint book reading across cultures: A comparison of Surinamese-Dutch, Turkish-Dutch, and Dutch parent-child dyads. Journal of Literacy Research, 32, 53–76.

Burgess, R. B., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one- year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37, 408–426.

Carretti, B., Borella, E., Cornoldi, C., & De Beni, R. (2009). Role of working memory in explaining the performance of individuals with specific reading comprehesion difficulties: A meta-analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 19, 246–251.

Catts, H. W. (2009). The narrow view of reading promotes a broad view of comprehension. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in schools, 40, 178–183.

Clay, M. (1979). Stones. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Clay, M. (1989). Concept about print in English and other languages. The Reading Teacher, 42(4), 268–276.

Cunningham, A. E. (2010). Tell me a story: Examining the benefits of shared reading. In D. K. Dickinson & S. B. Neuman (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of Early Literacy Research, vol. 3. New York: Guilford.

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1998). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22(1–2), 8–15.

DeBaryshe, B. D., Buell, M. J., & Binder, J. C. (1996). What a parent brings to the table: Young children writing with and without parental assistance. Journal of Literacy Research, 28, 71–90.

De Temple, J. M., & Snow, C. (1996). Styles of parent-child book reading as related to motherʼs view of literacy and childrenʼs literacy outcomes. In J. Shimron (Ed.), Literacy and education: Essays in memory of Dina Feitelson (pp. 49–68). Cresskill: Hampton.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1981). Peabody picture vocabulary test. San Antonio: Pearson Publishers.

Evans, M. A., Shaw, D., & Bell, M. (2000). Home literacy activities and their influence on early literacy skills. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 54, 65–75.

Feitelson, D., Goldstein, Z., Iraqi, U., & Share, D. (1993). Effects of listening to story reading on aspects of literacy acquisition in a diglossic situation. Reading Research Quarterly, 28, 70–79.

Ferguson, C. A. (1971 [1962]). Problems of Teaching Languages with Diglossia. In A. Dil (ed.). Language Structure, Language Use: Essays by Charles A. Ferguson (pp. 71–86). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gallili, S. (2006). Maternal mediation in book reading, maternal beliefs and child literacy: A comparison between two social groups. Thesis submitted to MA degree. School of Education, Bar-Ilan University.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hecht, S. A., Burgess, S. R., Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (2000). Explaining social class differences in growth of reading skills from beginning kindergarten through fourth-grade: The role of phonological awareness, rate of access and print knowledge. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12, 99–127.

Hirsch, E. D. (2003). Reading comprehension requires knowledge of words and the world. American Educator, 27, 10–13, 16–22, 28–29, 48.

Holes, C. (1995). Modern Arabic—structures, functions and varieties. London: Longman.

Ibrahim, R., & Eviatar, Z., & Aharon-Peretz, J. (2002). The characteristics of Arabic orthography slow its processing. Neuropsychology, 16, 322–326.

Korat, O. (2011). Emergent literacy development in socio-economic context: Parental mediation in book reading and beliefs on literacy support. In O. Korat & D. Aram (Eds.), Literacy and Language: Relationship bilingualism and difficulties (pp. 233–246). Jerusalem: The Hebrew University (Hebrew).

Korat, O., & Levin, I. (2002). Spelling acquisition in two social groups: Mother-child interaction, maternal beliefs and childʼs spelling. Journal of Literacy Research, 43, 209–236.

Korat, O., Bachar, E., & Snapir, M. (2003). Functional-social and cognitive aspects in emergent literacy: Relations to SES and to reading-writing acquisition in first grade. Megamot, 42, 195–218. (Hebrew).

Korat, O., Klein, P. S., & Segal-Drori, O. (2007). Maternal mediation in book reading, home literacy environment, and children’s emergent literacy: A comparison between two social groups. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 20, 361–398.

Leseman, P. P. M., & de Jong, P. F. (1998). Home Literacy: Opportunity, instruction, cooperation and social- emotional quality predicting early reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 33, 294–318.

Levin, I., & Korat, O. (1993). Sensitivity to phonological, morphological and semantic cues in early reading and writing in Hebrew. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 39, 213–232.

Levin, I., & Aram, D. (2012). Mother-child joint writing and storybook reading and their effects on kindergartnersʼ literacy: An intervention study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9254-y.

Levin, I., Share, D. L., & Shatil, E. (1996). A qualitative-quantitative study of pre-school writing: Its development and contribution to school literacy. In M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 271–293). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Levin, I., Saiegh-Haddad, E., Hende, N., & Ziv, M. (2008). Early literacy in Arabic: An intervention study among Israeli Palestinian kindergartners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 29, 413–436.

Lightfoot, C., & Valsiner, J. (1992). Parental belief systems under the guidance of the construction of personal cultures. In I. E. Siegel, A. V. McGillicuddy De-Lisi & J. J. Goodnow (Eds.), Parental belief systems: The psychologicalconsequences for children (pp. 393–414). Hillsdale: England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lonigan, C. J., & Whitehurst, G. J. (1998). Relative efficacy of parental and teacher involvement in a shared reading intervention for pre-school children from low income background. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13, 263–290.

McBride-Chang, C., Chow, Y. Y. Y., & Tong, X. (2010). Early literacy at home: General environnemental factors and specific parent input. In D. Aram & O. Korat (Eds.), Literacy development and enhancement across orthographies and cultures. In J. R. Malatesha (Series Ed.), Literacy studies. Perspectives from cognitive neurosciences, linguistics, psychology and education (pp. 97–110). New York: Springer.

Meesls, G. (1979). The Arabic that we learn and teach. Contemporary Arabic Teaching, Booklet 1. Tel-AvivUniversity and Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (August, 2001). Fostering spoken and written language in kindergartens. Department of Curriculum Planning.

Nevo, B., & Oren, A. (1979). Advanced processing steps used in Pea body test in Israel. Report No, 43, Haifa University.

Ninio, A. (1980). Picture-book reading in mother-infant dyads: Belonging to two subgroups in Israel. Child Development, 51, 587–590.

Olson, D. R. (1984). See jumping! Some oral language antecedents of literacy. In H. Goelman, A. Oberg, & F. Smith (Eds.), Awakening to literacy (pp. 185–192). Exeter: Henemam.

Purcell-Gates, V. (1996). Story coupons and TV guide: Relationship between home literacy Experiences and emergent literacy knowledge. Reading Research Quarterly, 31, 406–428.

Raz, I. S., & Bryant, P. (1990). Social background, phonological awareness and children`s reading. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 8, 209–225.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2003). Linguistic distance and initial reading acquisition: The case of Arabic diglossia. Applied Psycholinguistic, 24, 115–135.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2004). The impact of phonemic and lexical distance on the phonological analysis of words and pseudo-words in a diglossic context. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25, 495–512.

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2007). Linguistic constraints on childrenʼs ability to isolate phonemes in Arabic. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 605–625.

Saiegh-Haddad, E., Levin, I., Hende, N., & Ziv, M. (2011). The linguistic affiliation constraint and phoneme recognition in diglossic Arabic. Journal of Child Language, 38, 297–315.

Sénéchal, M., LeFevre, J., Thomas, E. M., & Daley, K. E. (1998). Differential effects of home literacy experiences on development of oral and literary language. Reading Research Quarterly, 33, 96–116.

Shatil, E. (2001). Haver Hadash [A new friend]. Adaptation version of Concept About Print Test to Hebrew. Kiryat Bialeek. Israel: Aah Publishing.

Shatil, A., & Navo, B. (2007). Test of listening comprehension of sentences. Haifa University.

Sigel, I. E. (1982). The relation between parental distancing strategies and the child’s cognitive behavior. In L. M. Laosa & I. E. Sigel (Eds.), Families as learning environments for children (pp. 47–86). New York: Plenum.

Somah, S. (1980). The question of the new Arab literature and language. Contemporary Arabic Teaching, 2. Tel Aviv University and Ministry of Education, Jerusalem.

Sonnenschein, S., & Munsterman, K. (2002). The influence of home based reading interactions 5-yearsʼ reading motivations and early literacy development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17, 318–337.

Stanovich, K. H., & West, R. F. (1989). Exposure to print and orthographic processing. Reading Research Quarterly, 24, 402–433.

Stuart, M., Dixon, M., Masterson, J., & Quinlan, S. (1998). Learning to read at home and at school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68, 3–14.

Treiman, R. (1993). Beginning to spell: A study of first grade children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Kleeck, A., & Stahl, S. A. (2003). Preface. In A. van Kleeck, S. A. Stahl & E. B. Bauer (Eds.), On reading books to children (pp. vii–xiii). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Walker, D., Greenwood, C., Hart, B., & Carta, J. (1994). Prediction of school outcomes bases on early language production and socioeconomic factors. Child Development, 65, 606–621.

Wasik, H. B., & Herrmann, S. (2004). Family literacy: History, concepts, services. In B. H. Wasik (Ed.), Handbook of family literacy (pp. 82–99). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wells, G. (1985). Pre-school literacy related activities and success in school. In D. Olson, G. Torrance & A. Hildyard (Eds.), Literacy, language and learning: The nature and consequences of reading and writing (pp. 229–255). Cambridge, University Press.

Wertsch, J. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Worzalla, S., Pess, R., Taub, A., & Skibbe, L. (2009, June). Parent writing instruction and pre-schoolersʼ writing outcomes. Paper presented at the Society for Scientific Studies of Reading conference. Boston.

Zuzovsky, R. (2011). The socio-economic background and the reading achievements gap between Hebrew and Arabic speaking children. In O. Korat & D. Aram, Literacy and Language: Relationship bilingualism and difficulties (pp. 31–57). Jerusalem: The Hebrew University (Hebrew).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Korat, O., Aram, D., Hassunha-Arafat, S., Saiegh-Haddad, E., Hag-Yehiya Iraki, H. (2014). Mother-Child Literacy Activities and Early Literacy in the Israeli Arab Family. In: Saiegh-Haddad, E., Joshi, R. (eds) Handbook of Arabic Literacy. Literacy Studies, vol 9. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8545-7_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8545-7_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-8544-0

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-8545-7

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)