Abstract

In this chapter, I define wisdom as a real-life process that is manifested when a person integrates conflicting ideas, and embodies those integrated ideas in actions that generate positive effects for oneself and others. From this perspective, I argue that wisdom involves both general and personal aspects. Personal involvement is vital for the manifestation of wisdom; successful attempts to pursue a good life for oneself and at the same time to help others live better lives are often valued as manifestations of wisdom. However, the overall effects that wisdom generates inevitably go beyond personal boundaries and affect others who benefit over the long term from wise decisions and actions. Historically, manifestations of wisdom have often pushed the boundaries of standards we use to evaluate the good life and have transformed the world we live in. Because people manifest wisdom and develop the ability to manifest wisdom in their own lives, it is important that we study wisdom in real-life contexts. I also discuss methods that can be used to study wisdom in real-life contexts, findings of some recent studies of wisdom in real-life contexts, as well as future directions for this branch of wisdom studies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

People manifest wisdom in real-life contexts through events in their own lives (Baltes & Smith, 1990; Kramer, 1990; 2000; Sternberg, 2007; Yang, 2008b). The ability to manifest wisdom is also developed through real-life learning. To understand wisdom, we must therefore examine wisdom as it is manifested real-life context. This chapter defines wisdom as a real-life process that is manifested when a person integrates conflicting ideas, and embodies those integrated ideas in actions that generate positive effects for oneself and others. It proposes an approach to real-life studies of wisdom in four parts. The first part provides theoretical arguments for studying wisdom in real life. The second part discusses some of the methodological issues encountered in real-life wisdom studies. The third part presents the findings of some recent studies of wisdom in real-life contexts. The fourth part discusses future directions for this branch of wisdom studies.

Theoretical Arguments

The Purpose of Studying Wisdom

Why should we study wisdom? Wisdom enables us to live a good life (Assmann, 1994; Holliday & Chandler, 1986). Although adaptation for survival is important for all living creatures, human civilizations have progressed to a point that biological survival or reproduction is not the sole purpose of life, as Jürgen Habermas (1968) asserted: “What may appear as naked survival is always in its roots a historical phenomenon. For it is subject to the criterion of what a society intends for itself as the good life” (p. 313). In general, most people strive to live well: to live with comfort, quality, dignity, happiness, and a sense of purpose and, in short, to live a life in which human potential is fully actualized, in which wonderful and satisfying things can happen.

Wisdom and Good Lives in Human Society

Wisdom is manifested as the result of the pursuit of a good life. Studies show that there is consensus over what constitutes a good life among members in different communities (Suh, Diener, Oishi, & Triandis, 1998). To most people, it is a life that is meaningful and satisfying (King & Napa, 1998). However, because Homo sapiens are social animals, our striving to live good lives also necessarily influences the lives of others. Recent events, such as global warming, shortage of natural resources, financial crises, and cultural and religious conflicts, are good examples of such interrelatedness. A good life, thus, must entails generating positive effects not only for oneself but also for others. Wisdom, as a process of pursuing a good life and resolving real-life problems by exerting positive influence both for oneself and others, has its foundation in human society.

A Good Life

In The Records of the Grand Historian (97 B.C./1974), one of the best known historical texts in ancient China, the famous historian Szuma Chien, recorded a historical event concerning a crucial battle that I think reveals a sharp contrast between two different conceptions of a good life:

Chao Sheh was a very capable general in the State of Chao in the Warring States Period of ancient China (403 B.C.–221 B.C.), and he won battles in the most desperate situations. In 260 B.C. the mighty State of Chin [the state that unified China in 221 B.C.] attacked the State of Chao. At that time Chao Sheh had already died. The young king of Chao wanted to appoint Sheh’s son Chao Kuo to be the commander….

Chao Kuo [the son] had studied military science and discussed strategy since boyhood. He was confident that no one in the world was a match for him. Once he even bettered his father Chao Sheh in a discussion on strategy, yet he could not win his father’s approval. When Chao Kuo’s mother asked why, Chao Sheh [the father] said, “War is a matter of life and death, but he makes light of it. I can only hope he never becomes our state’s commander. If he does, he will destroy our army.”

…. So when Chao Kuo [the son] was about to set out with his troops, his mother wrote to beg the king not to send him. Asked for her reasons, she replied, “When I was first married to his father [Sheh], who was then a commander, he offered food and wine to dozens of men at his meals and treated hundreds as his friends, distributing his gifts from Your Majesty and others of the royal house among his officers and friends. From the day he took the command he gave no further thought to family affairs. But as soon as Chao Kuo [her son] became a commander he put on such airs that none of his officers or men dare look him in the eye. When you give him gold and silk he takes it home, and he looks every day for cheap property to buy. How does he compare with his father, would you say? Since father and son are so different, I hope you will not send him.”

“Leave it to me,” said the king. “I have made the decision.” … After Chao Kuo [the son] took over, he rescinded all previous orders and appointments. When General Pai Chi of the State of Chin learned of this, he made a surprise attack, feigned a retreat, cut Chao’s supply route and split the army into two so that both officers and men lost heart. When his army was starving some forty days later, Chao Kuo led picked troops out to fight and the men of Chin shot and killed him. The State of Chao was defeated and hundreds of thousands of its men surrendered, only to be buried alive by the State of Chin. In all, the State of Chao lost four hundred and fifty thousand men [450,000]. (Chapter 81, trans. 1974)

This disastrous battle, which is known as the Battle of Changping (長平之戰), was considered a decisive battle that ultimately allowed the State of Chin to conquer other states and unify China decades later (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Changping).

Chao Sheh [the father] is by no means a prominent figure in ancient Chinese history. His name was recorded in history probably because of his son’s horrible failure. By modern standards, we can hardly assert that the father had a good life. Reading through the text, he probably did not enjoy many peaceful meals, accumulate much wealth, or have much family time, whereas the son was rich and received recognition while alive. However, it is only by comparison with the son’s failure that we realize how many lives were saved by the father’s efforts. Between the two, who do we say had a good life?

In terms of its temporal length, “life” here can have at least three different meanings. First of all, life can mean everyday life or a sequence of moments. Hence, to live a good life in this sense means having as many wonderful and fulfilling moments as possible. Second, life can mean an individual’s complete life course. Thus, living a good life means managing a life course so that it is fulfilling and satisfying. Third, life can also mean that which “existed before we were born and will continue to exist after we leave this world” (Coelho, 1994, p. 175). In this case, to live a good life means advancing human possibilities (Wittgenstein, 1953/1958) so that future generations may have even better lives than were possible before. Thus, wisdom can be manifested in real life in at least three forms, depending on its form and temporal length: (1) successfully resolving real-life problems and challenges, (2) managing one’s overall life course in a satisfying way, and (3) actualizing new possibilities in human civilization.

Positive Effects

One essential feature of wisdom is its positive effects on real-life situations (Yang, 2005). Examples of wisdom’s positive effects can be drawn from the biblical story of King Solomon, a figure who has been seen as an icon of wisdom for centuries in many Western societies. According to Kings I, Solomon was granted wisdom by God early in his life and reign (3:9–15), but his wisdom climaxed with the verdict he gave in the trial between two prostitutes over the maternity of a young boy:

The king said, “This one says, ‘My son is alive and your son is dead,’ while that one says, ‘No! Your son is dead and mine is alive.’” Then the king said, “Bring me a sword.” So they brought a sword for the king. He then gave an order: “Cut the living child in two and give half to one and half to the other.” The woman whose son was alive was filled with compassion for her son and said to the king, “Please, my lord, give her the living baby! Don’t kill him!” But the other said, “Neither I nor you shall have him. Cut him in two!” Then the king gave his ruling: “Give the living baby to the first woman. Do not kill him; she is his mother.” When all Israel heard the verdict the king had given, they held the king in awe, because they saw that he had wisdom from God to administer justice. (The Holy Bible, 1973, 1 Kings 3:16–28, New International Version)

In the story, Solomon’s power, the infant’s well-being, the infant’s mother, and even the state of Israel are all positively affected by Solomon’s judgment. Thus, when wisdom is manifested in real life, it generates positive effects for both the self and for others. Wisdom is manifested when positive, life-promoting effects result from the application of ideas in a real-life context.

In addition, a wise solution to a real-life dilemma sometimes dissolves the problem altogether and hence prevents further problems from materializing; as Wittgenstein (1922) observes: “The solution to the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem” (6.521).

However, Solomon’s unwise actions and egregious mistakes later in his life (1 Kings 11) make clear that there is no guarantee that a person who has great potential for wisdom will manifest it in real life at all times. A good life and, hence, wisdom can be judged more clearly by examining overall effects over the long run.

The Relationship Between Personal and General Aspects of Wisdom

Ultimately, wisdom deals with the pursuit of a good life for all. This observation raises a question concerning whether a distinction made between general and personal wisdom is a useful conceptual tool (Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). In my opinion, perhaps a better distinction is between the differing scopes of positive influence that wisdom generates. Evidently, the more that people identify the consequences of a decision or an action as positive, and the longer they evaluate them as positive, the greater the wisdom that has been manifested.

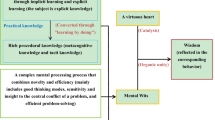

The term “personal wisdom” represents psychologists’ efforts to study wisdom manifested in real life through scientific reasoning and methods that are available to them. This term is useful because wisdom always begins with individuals. Wisdom begins to manifest when a person strives to live what he or she conceives of as the good life by cognitively integrating what are normally thought to be separate ideas or conflicting ideals, and it is manifested when a person acts based on these integrated thoughts in a way that generates lasting positive effects (Yang, 2008a). In addition, manifestations of wisdom in real life involve tacit knowledge—knowledge that can only be acquired by a person’s participation in endeavors of a particular community (Polanyi, 1958; Sternberg, 1998). Thus, wisdom, as we observe it in real life, defies decontextualized abstraction to a certain extent and cannot be fully expressed in words.

On the other hand, the overall effects that wisdom generates inevitably go beyond personal boundaries and affect others who sustain the consequences of wise judgments and actions. Wisdom is thus a positive process that is also observed, evaluated, valued, and transmitted within a structured group of people—the members of a society. Hence, what wisdom entails cannot be just personal.

Wisdom thus involves both general and personal aspects. The relationship between personal and general aspects of wisdom can be delineated from the perspective of historical development, through the dialectic between our personal attempts to live a good life and the evolution of general knowledge.

General Aspects of Wisdom

General aspects of wisdom involve consensus on what constitutes a good life and general knowledge of how this may be achieved.

Consensus on a Good Life

Because a good life is good not only for the individual but for others as well, the effort to live a good life in human society is evaluated not only by experts in certain fields but also by people who participate in that effort and share in its consequences. No matter how well a person reacts to or copes with a situation, resolves a problem, or manages his or her life, the positive and satisfactory effects of wisdom have to be recognized by at least some members of the society (Wittgenstein, 1953/1958). Only then can we say that wisdom has manifested in the real-life situation. Hence, the evaluation of a good life and wisdom is based on the common agreement of a community.

General Knowledge of Living a Good Life

Common agreement concerning the nature of a good life and wisdom, influences, and is influenced by, the knowledge transmitted by societies. Early in Western civilization, when Aristotle proposed the distinction between philosophical/theoretical wisdom (sophia) and practical wisdom (phronesis), the contemplation of a universal truth and rational thinking through syllogism were not commonly practiced. Although both sophia and phronesis were thought to help people to live a good life, higher value was attached to philosophical/theoretical wisdom, which deals with the invariant abstract and leads people to the truth (Osbeck & Robinson, 2005). After philosophical/theoretical wisdom was incorporated into education (Kitchener & Brenner, 1990), it became widespread and eventually became part of the body of general knowledge and then gave rise to sciences.

During the Renaissance, Descartes, by devoting himself to the tradition of searching for universal truth, made the most extreme argument concerning general wisdom:

For sciences as a whole are nothing other than human wisdom, which always remains one and the same, however different the subjects to which it is applied, it being no more altered by them than sunlight is by the variety of the things it shines on. Indeed, it seems strange to me that so many people should investigate with such diligence the virtues of plants, the motions of the stars, the transmutations of metals, and the objects of similar disciplines, while hardly anyone gives a thought to good sense—to universal wisdom. For every other science is to be valued not so much for its own sake as for its contribution to universal wisdom. …, what makes us stray from the correct way of seeking the truth is chiefly our ignoring the general end of universal wisdom and directing our studies towards some particular ends. (Rule One, Rules for the Direction of the Mind, [Ch. Adam & P. Tannery X: 359–361], in Cottingham, Stoothoff, & Murdoch, 1985, pp. 9–10)

According to Descartes, “the word ‘philosophy’ means the study of wisdom, and by ‘wisdom’ is meant not only prudence in our everyday affairs but also a perfect knowledge of all things that mankind is capable of knowing, both for the conduct of life and for the preservation of health and the discovery of all manner of skills” (Preface to the French edition of Principles of Philosophy, 1647, [Ch. Adam & P. Tannery IXB: 2], in Cottingham et al., 1985, p. 179).

Descartes’ proposal was later incorporated into the field of psychology. As psychologists over the past century shaped their discipline, they modeled it after the natural sciences, such as physics, with the explicit goal to study natural laws in human behavior (Fancher, 1990). As a result, when applied to the social realm, the closest place one could expect to find such natural laws and order is where the behavior of a group of people shows definite and regular patterns over a certain amount of time. In other words, psychologists study regularities people in a society normally exhibit, with some minor individual variations. From those social regularities, universal laws and general knowledge are derived (Popper, 1959). Psychologists generally assume that such laws and knowledge can exist independently of the societal context that gives rise to them without their meanings being distorted (Polanyi, 1958).

Throughout human history, the effort to live a good life has occurred in many different cultural contexts. Successful attempts to live a good life are often emulated and tested by others. Attempts that have led to genuine and positive influences in helping people to live good lives are valued as past achievements and are often passed down from generation to generation in these particular cultural contexts. Over time, formalized procedures general enough to be implemented by most people have developed through these new attempts to live a good life. They consist of maxims such as “do not do unto others what you would not have others do unto you” (Confucius: The Analects, 1979), and edicts such as the Rights of Man (Droite d’Hommes) proposed in France in 1789, the Slavery Abolition Act adopted in 1833 in the UK, women’s suffrage, as well as more general knowledge such as basic urban planning, modern practices of personal hygiene, common nutrition knowledge, and many others.

These are pieces of general knowledge that are commonly agreed on by members of specific cultures and thus preserved in customs, languages, symbol systems, organizational regulations, and domains of knowledge (Wittgenstein, 1953/1958). Habermas in his Knowledge and Human Interests (1968) noticed the connection between our striving for a good life and formalized knowledge: “The truth of statements is linked in the last analysis to the intention of the good and true life” (p. 317). In this way, general knowledge shapes parts of the world that we live in. Our conceptions of a good life are thus reshaped by those new pieces of general knowledge as they create new social regularities (Kuhn, 1962). These universal laws and the general knowledge concerning how to live a good life constitute general aspects of wisdom, which many believe can apply to most people in different societies.

Personal Aspects of Wisdom

Paradoxically, it is the preoccupation with universal laws that has kept contemporary philosophers, ethicists, and psychologists from discussing wisdom as an object of study (Assmann, 1994). Polanyi observes:

This ideal of universal knowledge is mistaken, since it substitutes for the subjects in which we are interested a set of data which tell us nothing that we want to know…. This self-contradiction stems from a misguided intellectual passion – a passion for achieving absolute impersonal knowledge which, being unable to recognize any person, presents us with a picture of the universe in which we ourselves are absent. In such a universe there is no one capable of creating and upholding scientific values; hence there is no science. (1958, p. 140)

This argument holds true for the study of wisdom because personal involvement is vital for the manifestation of wisdom. After all, wisdom involves personal striving to live a good life. Moreover, cognitive integration of what are usually thought to be separate ideas and conflicting ideals, and the embodiment of this integration in real-life situation requires long-term personal effort.

Wisdom involves coping with real-life challenges. It is in this respect that wisdom is unlike intelligence, which may involve solving artificial problems derived from a particular symbolic system (e.g., mathematics, music; Gardner, 1983). As Thurstone (1924) once asserted, “intelligence and the capacity for abstraction are identical” (p. xv). An individual who has a significant amount of general life knowledge but leads a miserable life (based on the person’s own standards as well as others) is seldom viewed as wise. That person may be intelligent, but not wise. It is possible that these unwise individuals give no less sound advice than others whose deeds follow or even outweigh their words, but we seldom seek counsel from them.

Because integrating relevant pieces of information in a given context and forging a vision that opens up future possibilities cannot be accomplished by adhering to general knowledge alone, personal aspects of wisdom thus involve attempts to resolve unsolved problems, to clarify fuzzy ideas, to follow intuitive directions, and to foresee possibilities that are hidden to many. These attempts are ways to live a good life that have been tried out but are not tested and emulated by others, and hence are not integrated into systems of general knowledge. Personal aspects of wisdom thus involve new patterns of behavior, developing pieces of knowledge, and evolving parts of human civilization.

Participation in Human Society

To manifest wisdom in real life, we need to participate in human society to know its common agreements and social regularities. As Howard Gruber (1989) put it, “to be effective the creator must be in good enough touch with the norms and feelings of some others so that the product will be one that they can assimilate and enjoy. Even the person who is far ahead of the times must have some community, however limited or special, with whom to interact” (p. 14).

Imagine a person who, by acquiring all the necessary general knowledge of life from reading, provides advice for all kinds of important human problems from his or her armchair through his or her Internet communication with others, but has never left the armchair to interact with others, nor participated any activity in human society. Could this person’s activities result in wisdom?

If those problems are resolved by following that person’s advice, we might think that he or she is not too bad, but even this appraisal has its limitations. Without other people actually carrying out the advice, and using their own tacit knowledge in the process of applying the advice, it will not generate any positive effect. Moreover, the ability to identify real-life problem is directly related to a person’s vision for a good life and his or her striving to live it (Arlin, 1990). If a person spends most of his or her life time sitting in the armchair, it is doubtful that he or she knows what real-life problems really are, and it is unlikely he or she has the ability to resolve those problems without divine intervention.

To identify and resolve a significant real-life problem, one needs to be truly participating as a member in a human society to acquire adequate general and tacit skills and knowledge of life. It is perhaps by knowing general conceptions of a good life that we can distinguish a good life from an ordinary one. It is also by understanding social regularities that we distinguish wisdom from other accomplishments. Such knowledge of common agreements and social regularities are not taught explicitly but learned tacitly through real-life experiences (Polanyi, 1958).

Unusual Integration

When wisdom emerges in a real-life context, it always strikes us that something unusual has happened. Although there may well be many people who can resolve ordinary problems and manage their lives more or less adequately, they do not usually strike us as people who manifest wisdom. Wisdom tends to be manifested in contexts where the problems or challenges we face involve a certain degree of difficulty. It may be a very difficult problem that puzzles everyone and to which no one can find a good solution, even for after trying his or her best, or it may be an everyday challenge that is resolved in an extraordinary way.

As real-life problems and challenges that give rise to wisdom are often ill-structured and poorly defined, there may not be any known rule or standard method for resolving them (Arlin, 1990; Yang, 2008b). Multiple solutions seem viable, each with its own set of strengths and weaknesses (Sternberg, 1998). In addition, there may be no criterion for assessing the adequacy or correctness of these solutions. At times, “decisions, solutions, and judgments are acknowledged as wise because they push standards to their limit or create types of meta-standards that redefine the acceptable” (Arlin, 1990, p. 237).

A person who manifests wisdom may have to “cross a logical gap” (Polanyi, 1958, p. 123) that cannot usually be achieved by following existing rules or social norms. As Freeman (1985) points out, we often find ourselves celebrating after the fact someone’s good or wise judgment in having elected to pursue a course that, at the time it was taken, we were absolutely convinced was foolish. Using Solomon’s example, we can see that King Solomon had definitely come up with a solution that crossed a logical gap. His unusual way of handling the trial is what makes his verdict extraordinary.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s I Have A Dream is another good example of unusualness that opens up new possibilities. King and his contemporaries never encountered circumstances close to what he described in his speech: “On the hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood” (August 28, 1963; cited in King, 1983). In wisdom we find unusual integrations of what most deem separate ideas and conflicting ideals (Yang, 2001, 2008a, 2008b, 2011a). Without this kind of integration, we are merely being effective in following rules rather than displaying wisdom.

Embodiment

We need to implement our integrated ideas in real-life situations so that our visions of a good life are concretely embodied. Embodiment—carrying out ideas or visions through actual actions—is thus an essential component of wisdom. As Polanyi (1958) observes, “practical wisdom is more truly embodied in action than expressed in rules of action” (p. 54). It is by embodying our visions of a good life that we begin to tacitly acquire social regularities and foresee future possibilities. As we perform purposeful actions in daily life, we integrate all the atomic information that we are subsidiarily aware of in the context and bring it to bear on a focal target—the purpose of our action (Polanyi). While implementing our ideas, we gather what we tacitly know through real-life interactions in a context, such as common conceptions of a good life in a given society, conceptions of wisdom in a given culture, informal ethical rules of communities, self-knowledge, and the unspoken assumptions, needs, and implicit values of others. In the process, we examine our own beliefs and values, correct mistakes, revise our plans and strategies, set up new goals, view ourselves from an ever-widening perspective, and refine our vision of a good life.

Our embodiment of life-purposes shapes our personal worlds, although we are not aware of it most of the time. In 1989, after the Tiananmen Square protests, the Chinese government meant one thing to a human rights activist and quite another to a business person. Often, our embodiment can bring to us different experiences and lead us to encounter different sets of events. Sometimes, the experiences we have today depend on how well we dealt with some important events in the past. As one road leads to another, each step we take leads us to see different sets of social regularities and future possibilities (Frost, 1916/1969). Wisdom that is manifested in real life can thus lead us down a life path that is different from one in which no wisdom is manifested.

Just as Rome was not built in a day, great wisdom may take a long time to manifest. In the case of Chao Sheh discussed above, it probably took Sheh many experiences in combat and long involvement in the military to understand that life and death are not light matters. Daily practice and devotion to his goal of serving as a good general were necessary to gain respect from his followers and to give commands efficiently in times of emergency. By striving daily toward positive life purposes and fulfilling them in satisfying ways, we pave the way for future manifestations of wisdom. Eventually, people who have exerted the most widespread positive effects through many wise decisions and actions are regarded as wise persons.

Human Possibilities

It is through the embodiment of integrated ideas that human possibilities are actualized in a positive direction and our conceptions of a good life can continue to evolve through history. Hence, the commonly agreed standards for evaluating what constitutes a good life are constantly forming and reforming. As long as generations of individuals continue to manifest wisdom, they continue to make new contributions to improve the lives of many. As new visions of a good life are illustrated by past wisdom, the social regularities of what constitutes a good life will be constantly forming and reforming. A positive feedback system is thus created between persons, manifestations of wisdom, general knowledge of life, world we live in, and conceptions of a good life, in which each shapes the progress of the other. At the same time, some parts of general knowledge about life may become obsolete and forgotten. It is in this sense that evaluative criteria for wisdom are ever developing and thus cannot be stringently formalized.

A Process View of Wisdom

Wisdom manifested in real life thus covers a broad area and should not be limited to particular or personal boundaries. Although wisdom always begins in individuals, the wisdom process also consists of embodiment in action and the resulting positive effects, which influence multiple parties. In this way, wisdom is a positive process encompassing cognitive integration, embodiment, and positive effects for one’s self and others. Though ultimately wisdom promotes a good life for many, it is accomplished only after a person integrates ideas that are usually deemed disparate, puts the integrated thought into action, and as a result exerts positive influence over the life of the acting self as well as the lives of others (Yang, 2001, 2005, 2008a, 2008b, 2009, 2011a).

Methodological Propositions

On the Importance of Studying Wisdom in Real-Life Contexts

Wittgenstein (1953/1958) once asserted “The ideal ‘must’ be found in reality” (I:101). For over a century, the history of psychology has recorded psychologists’ attempts to study what they observed in real life. When Charles Spearman proposed the concept “general intelligence” (1904), he had the ambition to find a correspondence between “Intelligence of Life and Tests of the Laboratory” [capitalized by Spearman] (pp. 224–225) as well as “Science and Reality” (p. 204). Alfred Binet stressed that the analysis of human intelligence should be based on “observations taken from life” and “concrete facts” (Binet & Simon, 1916, p. 25). Gardner contends that “psychology must address the major issues of human existence” (1989, p. 49).

Thurstone, another prominent figure in intelligence theory and testing, noticed that “when we are studying human nature, either in the laboratory or in our daily lives, it is much more conducive to psychological insight to look for the satisfactions that people seek through their conduct than to judge them as merely responding to a more or less fortuitous environment” (1924, p. 164). He observed that scientific experimentation “seldom relates to the permanent life interests of the persons who lend their minds to the psychological experiments” (p. 4). He explained:

The normal person who has sufficient leisure to serve as a subject of experimentation in the psychological laboratory is not likely to have any major mental disturbance and distress. If, on the occasion of a peaceful psychological experiment, he is mentally disturbed by any serious issue in his fundamental life interests – financial, sexual, social, professional, physical – he reports that he is indisposed, and he does not serve as a subject. It is therefore relatively seldom that the psychological laboratory gets for observation persons who are in a mental condition of major significance. (pp. 3–4)

What we do in a psychological laboratory often has little to do with our lives the minute we walk out of the laboratory: This is not the case with wisdom. In real-life situations where wisdom is called for, we tend to live with the long-term consequences of the decisions we make and actions we take, be they right or wrong. Wisdom manifested in real life produces consequences that are irreversible. It is thus essential that we study wisdom in real-life contexts.

Decades ago, Kohlberg (1973) had already foreseen that “the study of lives may someday aid in the comprehension and communication of more adequate life meanings.… In the end, lives are studied so humans will learn how to live better” (p. 204). In the presence, one purpose of psychology is to help people to live a better life (Mission Statement, American Psychological Association, 2011). We can contribute to the fulfillment of this vision by striving to study wisdom in real life.

Methods for Studying Wisdom in Real-Life Contexts

We can understand wisdom in real life with the help of empirical methods. We first need to understand wisdom as it is preserved in languages and as it is commonly understood by investigating people’s conceptions of wisdom in different cultures. Because formal theories in psychology derive in part from scientists’ implicit theories of the construct under investigation, understanding implicit theories can provide a basis for explicit psychological theories (Sternberg, Conway, Ketron, & Berstein, 1981; Yang & Sternberg, 1997a, 1997b). Peoples’ informal conceptions of wisdom also serve to demarcate the conceptual boundary necessary for the development of formal wisdom theories (Sternberg, 1985). Methods such as prototypical studies, multidimensional scaling, factor analysis, cluster analysis of words related to wisdom, open-ended questionnaires, and structured interviews have proven to be effective in examining these conceptions of wisdom. Several studies have provided important insights into this aspect of wisdom (Clayton & Birren, 1980; Holliday & Chandler, 1986; Levitt, 1999; Sternberg, 1985; Yang, 2001).

Because tacit knowledge may not lend itself to observation from a third-person perspective and many reasoning and behavioral processes involved in manifesting wisdom in real life may be more difficult to detect by objective methods, retrospection elicited by qualitative methods such as interviews can be used to collect narratives from the first-person point of view and explore the psychological process of wisdom as it is manifested in real-life situations. Interviews concerning wise actions and their consequences in life management can highlight how daily-life events and life course are handled and managed, as well as real-life contexts where they occur. Thus, through the narratives of wisdom nominees, we can derive a clearer and more detailed look at how wisdom is manifested in the contexts of real people’s lives.

In addition, because generating positive effects is one of the defining features of wisdom, methods used to studying wisdom should also try to include the consequences and the ex post facto analysis of the visions, decisions, and actions involved in manifestations of wisdom. Studies based on nomination of wise individuals by those who witness embodiment and experience the beneficial consequences, as well as biographical and archival studies of wisdom nominees, can expand our understanding of wisdom from a long-term perspective and can be used to disclose positive possibilities open to others through the embodied visions of wise people.

Contexts are also important for the manifestation of wisdom. By comparing manifestations of wisdom in particular kinds of contexts, we can gain a more general understanding of how wisdom is manifested in real life. Similarly, learning from important life experiences is essential for the development of the ability to manifest wisdom in real-life situations. By comparing learning from various important life experiences that foster later manifestations of wisdom, we can gain a broader understanding of how abilities leading to manifestations of wisdom are developed. In addition, because wisdom as a real-life process is observed and evaluated by members of a society, quantitative methods can be used to examine how strongly the process and content are considered by others to be related to wisdom.

Empirical Findings

Previous studies have analyzed wisdom as it is commonly understood in real life among different cultural contexts (e.g., Clayton & Birren, 1980; Holliday & Chandler, 1986; Levitt, 1999; Sternberg, 1985; Yang, 2001) and have highlighted core components of wisdom (Yang, 2008a), the contexts and domains of life in which wisdom is mostly likely to be manifested, and the common functions of wisdom when it is manifested in real life (e.g., Bluck & Glück, 2004; Montgomery, Barber, & McKee, 2002; Yang, 2008b). In particular, leadership has been identified as an important context to study both the development and manifestation of wisdom in real life.

Conceptions of Wisdom in Different Cultural Contexts

Western Conceptions of Wisdom

Studies show that American conceptions of wisdom value reasoning ability, sagacity, learning from ideas and environment, judgment, expeditious use of information, and perspicacity (Sternberg, 1985). Canadian conceptions of wisdom value exceptional understanding of ordinary experience, judgment and communicative skills, general competencies, interpersonal skills, and social unobtrusiveness (Holliday & Chandler, 1986). Hispanic conceptions of wisdom emphasize spirituality (instead of cognition), attitude toward learning (instead of possession of knowledge), and acts of serving and caring (instead of giving good advice; Valdez, 1994).

Eastern Conceptions of Wisdom

Takayama (2002) found that Japanese people stress practical and experiential aspects of wisdom rather than abstract thinking. In Japan, wisdom consists of four core dimensions: knowledge and education, understanding and judgment, sociability and interpersonal relationships, and introspective attitudes (Takahashi & Overton, 2005). Results of my study (Yang, 2001) investigating the concept of wisdom in Taiwanese Chinese culture through examination of implicit theories of wisdom showed that for most Taiwanese Chinese individuals, a wise person has a broad range of competencies and knowledge, is benevolent and compassionate toward others, holds profound yet open-minded attitudes about life, and remains modest and unobtrusive in social interactions. For Tibetan Buddhist monks, wisdom includes attributes such as recognizing Buddhist truths, realizing that emptiness is the true essence of reality, becoming the nonself, existing beyond suffering, being honest and humble, being compassionate to others, respecting others, treating all creatures as worthy and equal, having the ability to distinguish good from evil, and being efficient in projects (Levitt, 1999).

Comparisons

A previous study found that Easterners tend to hold a more synthetic view of wisdom, stressing both cognitive and affective dimensions, whereas Westerners tend to emphasize only cognitive dimensions (Takahashi & Bordia, 2000). A comparison of Eastern and Western descriptions of wisdom found that Easterners tend to put a stronger emphasis on both action and its effects when discussing wisdom, whereas Western models of wisdom stress the cognitive over the notion of practical application (Yang, 2008a).

Wisdom in Real-Life Contexts

Core Elements of Wisdom: Integration, Embodiment, and Positive Effects

My study (Yang, 2001) of Taiwanese Chinese descriptions of a wise person identified three common themes: integration, embodiment, and positive effects. Two studies (both in Yang, 2008a) were conducted to test the proposed process view of wisdom by examining whether the three components of wisdom exist in real life. The first study conducted content analysis on the rationales for nominations of wise individuals, which were solicited from people in different walks of life, age groups, and educational levels in Taiwan. The second study investigated whether narratives of actual manifestations of real-life wisdom by wisdom nominees reveal the three components of wisdom, and whether emphasis of the three components affects raters’ evaluation of wisdom. The results of content analysis of nominators’ descriptions, nominees’ narratives, and raters’ evaluation showed that the three core components of wisdom play an important role in the descriptions, manifestation, and evaluation of wisdom.

Contexts and Functions of Wisdom in Real Life

Western Studies

Bluck and Glück (2004) investigated manifestations of wisdom from an autobiographical perspective using an “experienced wisdom” procedure in Germany. They found that wisdom is often manifested in the process of making life decisions, managing day-to-day lives, and reacting to negative events. In another study, Glück, Bluck, Baron, and McAdams (2005) found that wisdom manifested in three forms: “empathy and support” (i.e., seeing others’ perspectives and feelings, and helping them resolve difficult situations), “self-determination and assertion” (i.e., taking control of a situation and standing by one’s values, goals, or priorities), and “knowledge and flexibility” (i.e., relying on one’s own experience, having the ability to compromise, and showing tolerance for uncertainty).

Montgomery et al. (2002) studied real-life wisdom as observed by North American older adults and found that wisdom often manifests through guidance, knowledge, experience, moral principles, time, and compassionate relationships. Nominators of wise individuals in this study were more likely to describe the positive influences of wise persons as a form of received guidance from a first-person perspective. For example, when asked to describe a wise person, one participant said “I was inspired by him to go to college…. And I think that was a wise decision, and it was inspired by him” (p. 144).

Asian Studies

Results of my study (Yang, 2001), which collected behavioral attributes of wise persons, showed that descriptions of wisdom often include the handling of daily events (e.g., “Is able to transform an adverse situation to one’s or everyone’s advantage,” and “Is able to analyze and resolve problems and their causes”), managing one’s personal life (e.g., “Is able to make one’s life meaningful, worthwhile, fulfilling, and valuable,” and “Enjoys life fully; lives life with a sense of peacefulness and contentment”), and contributing to social improvement and progress (e.g., “Is able to make contributions enhancing and improving society,” and “Is able to bring harmony to society, home and others”).

In another study (Yang, 2008b), I asked Taiwanese Chinese nominated as wise persons to answer questions about the wisest things they have done. Content analysis of nominees’ narratives showed that in real-life contexts, manifestations of wisdom were prominent in nominees’ endeavors. When manifested in real life, wisdom often involves striving for common good by helping others and contributing to society, achieving and maintaining a satisfactory state of life, deciding and developing life paths, resolving difficult problems at work, and insisting on doing the right thing even when facing adversity.

The results also showed that a majority of manifestations of wisdom fell in the category of helping others and contributing to society. These manifestations were judged by raters as more related to nominees’ display of self-determination and assertion rather than empathy and support for other people. Wisdom nominees’ descriptions of the manifestations, such as caring for patients with terminal illnesses, suggested that wisdom is based more on a self-defined vision than on social obligations or duties.

Many nominees became aware of others’ needs when they themselves encounter difficulties earlier in life, yet their wisdom does not manifest while solving their own problems, but when they vow to make a difference by helping others who face similar problems. This finding demonstrates an integration of an individual’s own visions of a good life with an understanding of others’ plights. Nominees were able to integrate conflicting ideals regarding self and others by employing their personal experiences to empathize with others’ grievances. By quietly observing others’ needs, they generated support and concern that they themselves had not received.

Some manifestations of wisdom had widespread effects, extending to entire institutions or even society at large, while others benefited the immediate environment and those involved by keeping personal goals and morality intact. In addition, the interests of wisdom nominees and other interest groups sometimes remained unbalanced. Wisdom may involve people who commit themselves without reward and may also be found where some are kept from exploiting others.

The findings suggest that wisdom tends to be manifested in at least two real-life contexts. One context is developmental; in this context, wisdom involves life decisions and life management. Wisdom was found to be manifested through fulfilling visions of a good life or pursuing life missions. The other context is situational; in this context, wisdom is manifested in everyday situations by taking the form of solving problems or resolving crises. Wisdom was found to thrive when a person resolved difficult life problems or work-related problems in both ordinary and exceptional circumstances.

Wisdom and Leadership

Seen from the perspective that wisdom is a real-life process, wisdom is not a quality that can be developed intrapersonally; what can be developed is the ability to manifest wisdom. Different manifestations of wisdom require different sets of abilities, and these abilities can be developed through real-life experiences. Leadership involves dealing with human affairs in group contexts (Northouse, 2004). It is therefore an important context to study both the manifestation of wisdom and the development of abilities related to manifesting wisdom.

Wisdom Manifested Through Leadership

As can be seen from the stories of Solomon and Chao Sheh, when wisdom is exercised through leadership, it often generates pervasive positive effects (Küpers, 2007; Srivastva & Cooperrider, 1998) and helps more people to live a good life. Difficult problems, such as global warming and financial crises, may be resolved or avoided if leadership is executed with wisdom. Ultimately, wisdom manifested through leadership can pave the way to a better and brighter future.

In a Taiwan-based study (Yang, 2011a), I found that many individuals nominated as wise people had leadership responsibilities (60 %). This is similar to the results of a German study (56 %; Staudinger, 1996). Analysis of transcripts of interviews with wisdom nominees showed that many instances of wisdom involved leadership.

I also found that a significant number of leadership-related wisdom was manifested by leaders of nonprofit organizations. Leadership-related wisdom was often manifested through leaders’ influence on the society at a macro level, on organizations at a micro level, and also on younger generations. Leaders who were nominated as wise persons often strove to respond to certain societal needs; they often held ideals not only for those involved with their organizations but also for society in general. In addition, when wisdom nominees had no preexisting institution to help them fulfill their visions, they tended to create leadership responsibilities by founding their own organizations.

Wisdom and Learning from Important Leadership Experiences

Abilities to manifest wisdom can also be developed through leadership experience. Theoretically, a continuous process of learning from extensive real-life experience can foster the manifestation of wisdom (Küpers, 2007; Small, 2004; Staudinger, Smith, & Baltes, 1992; Sternberg, 1998; Yang, 2008a, 2008b). As an important developmental task, leadership exposes a person to a wide variety of human conditions, as well as difficult and constantly changing challenges and problems. Resolution of leadership-related problems and challenges in real life may pave the way for manifestation of wisdom in a later stage of life (Bierly, Kessler, & Christensen, 2000; Bigelow, 1992; Dittmann-Kohli & Baltes, 1990; Erikson, 1982; Kessler & Bailey, 2007; Smith, Staudinger, & Baltes, 1994; Yang, 2009, 2011a).

I studied the relationship between leadership learning and wisdom using a mixture of qualitative methods (interviews) and quantitative methods (statistical analysis; Yang, 2009). The results showed that learning acquired in leadership positions was judged by raters as involving more wisdom than learning acquired in subordinate positions. The study suggests that some leaders are able to transform learning they acquire from their leadership experiences into wisdom.

How does this transformation of leadership learning into wisdom take place? After gaining insights through integrating diverse perspectives and modes of operation (i.e., cognitive integration of different work domains, ideals and reality, and tact and tenacity), those leaders embody these integrated insights by making extra effort to share their experiences and thoughts within the organization. As a result, their satisfaction with the handling of human affairs increases, and their interpersonal skills, relationships, and networks expand and improve. Moreover, they are able to exert a positive influence on others by empowering members, making contributions, and serving communities outside the organization (Yang, 2011b).

Conclusions and Future Directions

To conclude, wisdom is manifested in real-life contexts, and the ability to manifest wisdom must also be developed through participation in handing real-life human affairs. As Birren and Fisher (1990) argue, “The various aspects of wisdom must apply to real people in real situations in real time” (p. 331). It is therefore important that we study wisdom in real life. Researchers need to investigate how perspectives are integrated, how learned lessons are applied, how visions for a good life are embodied in real life, and how these applications and embodiment help both oneself and others to live meaningful and satisfying lives.

We also need to pay attention to how different conceptions of a good life shape people’s life goals, how unique life visions are formed, and how these life goals and life visions in turn influence people’s manifestation of wisdom. Wisdom, which helps people to live a good life, is thus important to the study of lifelong learning; adult and higher education; counseling, developmental, and health psychology; and organizational management and leadership.

Whenever a question or a problem in reality takes a field of inquiry beyond its initial discussions and applications, the field extends its boundaries. I think that is the reason Spearman (1904) and Thurstone (1924) wrote their articles on intelligence with extensive discussion of science and psychology. As contemporary psychologists studying wisdom venture into uncharted areas, it is time to rethink our history, culture, methods, knowledge structure, and, most of all, ourselves. In the final analysis, it is through striving for wisdom through the most appropriate methods we know of and trying our best to define wisdom that we participate in the advancement of human civilization.

References

American Psychological Association. (2011). Mission statement. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/about/index.aspx

Arlin, P. K. (1990). Wisdom: The art of problem finding. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 230–243). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Assmann, A. (1994). Wholesome knowledge: Concepts of wisdom in a historical and cross-cultural perspective. Life-Span Development and Behavior, 12, 187–224.

Baltes, P. B., & Smith, J. (1990). Toward a psychology of wisdom and its ontogenesis. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 87–120). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bierly, P., Kessler, E., & Christensen, E. (2000). Organizational learning knowledge and wisdom. Journal of Organization Change, 13(6), 595–618.

Bigelow, J. (1992). Developing managerial wisdom. Journal of Management Inquiry, 1(2), 143–153.

Binet, A., & Simon, T. (1916). Upon the necessary of establishing a scientific diagnosis of inferior states of intelligence. In H. H. Goddard (Ed.), The development of intelligence in children (pp. 5–8). Washington, DC: University Publications of Americans. (Reprinted from Psychometrics and educational psychology, Vol. 4, pp. 9–36, by D. N. Robinson, Ed., 1977).

Birren, J. E., & Fisher, L. M. (1990). The elements of wisdom: Overview and integration. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 317–332). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bluck, S., & Glück, J. (2004). Making things better and learning a lesson: Experiencing wisdom across the lifespan. Journal of Personality, 72, 543–572.

Clayton, V. P., & Birren, J. E. (1980). The development of wisdom across the life span: A reexamination of an ancient topic. Life-Span Development and Behavior, 3, 103–135.

Coelho, P. (1994). By the river Piedra I sat down and wept (A. Clarke, Trans.). New York: HarperFlamingo.

Confucius: The Analects. (1979). (D. C. Lao, Trans.). New York: Penguin Books.

Cottingham, J., Stoothoff, R., & Murdoch, D. (1985). The philosophical writings of Descartes (Vols. 1–2). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dittmann-Kohli, F., & Baltes, P. B. (1990). Toward a neofunctionalist conception of adult intellectual development: Wisdom as a prototypical case of intellectual growth. In C. Alexander & E. Langer (Eds.), Higher stages of human development (pp. 54–78). New York: Oxford University Press.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York: Newton.

Fancher, R. E. (1990). Pioneers of psychology (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Freeman, M. (1985). Paul Ricoeur on interpretation: The model of text and idea of development. Human Development, 28, 295–312.

Frost, R. (1916/1969). The road not taken. In E. D. Lathem (Ed.), The poetry of Robert Frost. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1989). To open minds. New York: Basic Books.

Glück, J., Bluck, S., Baron, J., & McAdams, D. P. (2005). The wisdom of experience: Autobiographical narratives across adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 197–208.

Gruber, H. (1989). The evolving systems approach to creative work. In D. B. Wallace & H. E. Gruber (Eds.), Creative people at work. New York: Oxford University Press.

Habermas, J. (1968). Knowledge and human interests. Boston: Beacon.

Holliday, S. G., & Chandler, M. J. (1986). Wisdom: Explorations in adult competence. Contributions to Human Development, 17, 1–96.

Kessler, E. H., & Bailey, J. R. (2007). Introduction: Understanding, applying, and developing organizational and managerial wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), Handbook of organizational and managerial wisdom (pp. xv–lxxiv). Los Angeles: Sage.

King, C. S. (1983). The words of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York: Newmarket Press.

King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes life good? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 156–165.

Kitchener, K. S., & Brenner, H. G. (1990). Wisdom and reflective judgment: Knowing in the face of uncertainty. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 212–229). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kohlberg, L. (1973). Continuities in childhood and adult moral development revisited. In P. B. Baltes & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Life-span developmental psychology: Personality and socialization (pp. 179–204). New York: Academic.

Kramer, D. A. (1990). Conceptualizing wisdom: The primacy of affect-cognition relations. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Wisdom: Its nature, origins, and development (pp. 279–313). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kramer, D. A. (2000). Wisdom as a classical source of human strength: Conceptualization and empirical inquiry. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 83–101.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Küpers, W. M. (2007). Phenomenology and integral phenol-practice of wisdom in leadership and organization. Social Epistemology, 21(2), 169–193.

Levitt, H. M. (1999). The development of wisdom: An analysis of Tibetan Buddhist experience. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 39, 86–105.

Mickler, C., & Staudinger, U. M. (2008). Personal wisdom: Validation and age-related differences of a performance measure. Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 787–799.

Montgomery, A., Barber, C., & McKee, P. (2002). A phenomenological study of wisdom in later life. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 54, 139–157.

Northouse, P. G. (2004). Leadership theory and practice (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Osbeck, L. M., & Robinson, D. N. (2005). Philosophical theories of wisdom. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), Handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 61–83). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Popper, K. R. (1959). The logic of scientific discovery. New York: Basic.

Small, M. W. (2004). Wisdom and now managerial wisdom: Do they have a place in management development programs? The Journal of Management Development, 23, 751–764.

Smith, J., Staudinger, U. M., & Baltes, P. B. (1994). Occupational settings facilitating wisdom-related knowledge: The sample case of clinical psychologists. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 989–999.

Spearman, C. (1904). “General intelligence”, objectively determined and measured. The Journal of Psychology, 15(1), 201–293.

Srivastva, S., & Cooperrider, D. L. (Eds.). (1998). Organizational wisdom and executive courage. San Francisco: The New Lexington Press.

Staudinger, U. M. (1996). Wisdom and the social-interactive foundation of the mind. In P. B. Baltes & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), Interactive mind: Life-span perspectives on the social foundation of cognition (pp. 276–315). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Staudinger, U. M., Smith, J., & Baltes, P. B. (1992). Wisdom-related knowledge in a life review task: Age differences and the role of professional specialization. Psychology and Aging, 7(2), 271–281.

Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Implicit theories of intelligence, creativity, and wisdom. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 607–627.

Sternberg, R. J. (1998). A balance theory of wisdom. Review of General Psychology, 2, 347–365.

Sternberg, R. J. (2007). A system model of leadership. The American Psychologist, 62(1), 34–42.

Sternberg, R. J., Conway, B. E., Ketron, J. L., & Berstein, M. (1981). People’s conceptions of intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 37–55.

Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Triandis, H. C. (1998). The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgements across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 482–493.

Szuma Chien (97 B.C./1974). The records of the grand historian. (H.-Y. Yang & Y. Gladys, Trans.). Hong Kong: The Commercial Press.

Takahashi, M., & Bordia, P. (2000). The concept of wisdom: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Psychology, 35, 1–9.

Takahashi, M., & Overton, W. F. (2005). Cultural foundations of wisdom: An integrated developmental approach. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Jordan (Eds.), A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives (pp. 32–60). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Takayama, M. (2002). The concept of wisdom and wise people in Japan. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Tokyo University, Japan.

The Holy Bible, New International Version. (1973). Colorado Springs, CO: International Bible Society.

Thurstone, L. L. (1924). The nature of intelligence. London, UK: Routledge.

Valdez, J. M. (1994). Wisdom: A Hispanic perspective (Doctoral dissertation, Colorado State University, 1993). Dissertation International Abstract, 54, 6482-B.

Wittgenstein, L. (1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. New York: Kegan Paul.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953/1958). Philosophical investigations. (3rd ed., G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Basil Blackwell & Mott, Ltd.

Yang, S.-Y. (2001). Conceptions of wisdom among Taiwanese Chinese. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 662–680.

Yang, S.-Y. (2005). 當創造與智慧相遇。台灣華人文化中創造力與智慧的關係[When creativity meets wisdom: The relationship between creativity and wisdom in Taiwanese Chinese culture]. 教育資料集刊 [Bulletin of National Institute of Educational Resources and Research], 30, 47–74.

Yang, S.-Y. (2008a). A process view of wisdom. Journal of Adult Development, 15(2), 62–75.

Yang, S.-Y. (2008b). Real-life contextual manifestations of wisdom. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 67(4), 273–303.

Yang, S.-Y. (2009). 智慧與領導智慧與領導:高等教育場域中的經驗學習 [Wisdom and leadership: Experiential learning in contexts of higher education]. 教育政策論壇 [Educational Forum], 12(3), 125–162.

Yang, S.-Y. (2011a). Wisdom displayed through leadership: Exploring leadership-related wisdom. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 616–632.

Yang, S.-Y. (2011b). Leadership learning and the manifestation of wisdom. Unpublished manuscript, National Chi Nan University, Puli, Taiwan.

Yang, S.-Y., & Sternberg, R. J. (1997a). Taiwanese Chinese people’s conceptions of intelligence. Intelligence, 25(1), 21–36.

Yang, S.-Y., & Sternberg, R. J. (1997b). Conceptions of intelligence in ancient Chinese philosophy. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 17(2), 101–119.

Acknowledgement

The preparation of this chapter is partly supported by National Science Council, Taiwan under the grant numbered 97-2410-H-260-005-SS2 and 99-2410-H-260-006-MY2. I would like to thank Professor Michel Ferrari for his very helpful comments on earlier draft of this chapter. Many thanks are to Dr. Lacy Johnson, Dr. Christine Jensen, and Dr. Robert Reynolds for their invaluable editing help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Yang, Sy. (2013). From Personal Striving to Positive Influence: Exploring Wisdom in Real-Life Contexts. In: Ferrari, M., Weststrate, N. (eds) The Scientific Study of Personal Wisdom. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7987-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7987-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-7986-0

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-7987-7

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)