Abstract

The question of whether religion and religiosity is positively or negatively related to social trust has been widely debated. In this chapter we will, using data from a local level survey on trust in Sweden, test whether religiosity as belief and religion as social organization correlate in any way with social trust in the specific case of a highly secular society. We are applying a multilevel approach in which we introduce both individual and contextual level data (church attendance and church membership) and where our focus will be on the local or community level. We conclude that while general surveys on trust suggest, if anything, a negative relationship between religiosity and social trust, one can, even in a highly secular country like Sweden, identify a modest positive correlation between trust and religion, which, however, is limited to religion as social organization.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

6.1 Why Study Religion and Trust?

The argument for studying the possible relation between religion and trust is linked to the debate regarding the conditions under which social trust is created, continues to thrive, comes under pressure, and is undermined. Two fundamental premises inform this debate, and before we delve into the more specific question of the role of religion, let us briefly provide this broader context.

The first premise is the idea that, in the words of Sissela Bok (1978: 26), “when trust is destroyed, societies falter and collapse.” While some scholars (see, e.g., Hardin 1999; Patterson 1999) also note the role of distrust as a necessary antidote to blind trust and naïve gullibility, most economists, psychologists, sociologists, political scientists, and management theorists appear to agree that social trust is the glue that holds families, societies, organizations, and companies together (e.g., Fukuyama 1995; Seligman 1997; Bordum 2001). With it society will flourish, without it society will either fall apart or require sheer, repressive force to survive.

The second premise is that social trust is waning. Large-scale population surveys conducted throughout the world indicate that in some countries, most prominently the United States, both the general social trust the citizens have in each other and the confidence they have in the political system have declined. A recurrent theme in the analysis of why this decline is occurring is that trust is linked to traditional social practices, values, and institution – such as religion – that place commitment to community and civic virtue at the center of moral codes and values. These, it is argued, have increasingly been giving way to egotistic individualism, the central value of the modern market society, leading to suspicion of fellow citizens and common institutions (Putnam 2000).

This linkage of modernity to a decline in social cohesion and trust is not new (cf. Simmel 1950). Indeed, social theorists have long associated the rise of modern society with a shift from warm Gemeinschaft to cold Gesellschaft, leading with necessity to anomie, alienation, and a breakdown of social trust. According to thinkers as varied as Marx, Durkheim, Simmel, Weber, and Tönnies, modernity was characterized by selfish individualism, the freedom and anonymity of the big city, the loss of natural community, and deadening life in the “iron cage” dominated by the bureaucratic state and the ruthless market (Sztompka 1999). The underlying assumption of these theories is that that trust arises in small, closely knit communities where there is a large degree of interdependence. This nostalgic tradition has continued into our own time, through David Riesman’s famous analysis of solitude and alienation in post-World War II American mass society in The Lonely Crowd, through Christopher Lasch’s book on “narcissistic individualism” in the 1970s, to Ulrich Beck’s recent theories about the “risk society” (Riesman 1950; Lasch 1979; Beck 1992), and the laments of Putnam (2000) concerning the decline of social capital and the collapse of community.

In light of this long-standing tradition Delhey and Newton (2005: 311) have argued that it is a puzzle why social trust exists at all in large-scale and industrialized urban societies. Large-scale societies would arguably be less than ideal for the creation of social trust since social networks are thinner and weaker and people by and large do not know each other personally, but are linked only through what Benedict Anderson famously called the “imagined community” of the nation (Anderson 1983).

However, recent survey dataFootnote 1 suggest an opposite argument: the more traditional societies tend to have less trusting citizens. Indeed, it is precisely the most modern, individualistic, and secular countries, most notably the Nordic countries, that are characterized by broad social trust beyond the intimate sphere of family, clan, and friends. Indeed, as Delhey and Newton (2005) suggest, removing the Nordic countries from the analysis minimizes many of the correlations between trust and other variables, suggesting that the high-trust Nordic societies need to be investigated more closely to tease out what factor or factors that are more important as well as to what extent these are so inextricably linked so as to make it hard to disentangle them. However, these findings broadly suggest the possibility of a reversed causal chain, centered on the hypothesis that modern market societies are heavily dependent upon social trust in order to function. Social trust would then be understood as either a necessary precondition, a result from, or be mutually reinforced by modernity.

The possible linkages between trust and modernity or traditionalism bring to the fore the question of religion and religiosity’s relation to social trust. Insofar as (a) at least some very modern societies – Sweden being a prime case – stand out as secularized, and (b) religion in most accounts constitutes an important aspect of “traditionalism,” the question of whether religion plays a role in shaping, maintaining, or breaking social trust appears to be both crucial and potentially controversial in secularized societies, especially as they face increased immigration of more religious individuals, families, and communities.

The literature on the connection between religion and social trust is not settled, but we can broadly identify two main themes: one concerned with whether faith, belief, and dogma matter for trust and a second one asking if religion as organization or social network is linked to trust. The present study will, accordingly, attempt to investigate separately the effects on trust of religion as faith, on the one hand, and religion as social organization, on the other. Here we follow previous studies that have also argued for an operationalization that separates religiosity (in terms of belief and importance of religion in life) from religious practice (church attendance) both at the individual level and the community level (Halman and Draulans 2006; Putnam and Campbell 2010).

6.2 Religion as Theology and Belief

Classical sociological theorists have underlined the importance of religion for shaping citizens’ values and behavior. Max Weber argued, for example, that the protestant ethic underlined the importance of trust and trustworthy behavior, suggesting a direct accountability to God, which meant that less than diligent behavior would be noticed from “above” and be punished (Delhey and Newton 2005; Misztal 1996).

Another line of argument linking religiosity to trust is that religious people would appear more trustworthy than nonreligious people as most religions incorporate (moral) codes of conduct and tend to encourage diligent behavior and the following of rules and therefore spread more trust (Berggren and Bjørnskov 2011). A widespread trustworthiness among the citizens, through for instance the religiously imposed codes of conduct, would in turn facilitate the creation of social trust (Rothstein 2005). If others assume that most people are religious and that religious people are more diligent and trustworthy, there ought to be a positive correlation between the proportion of religious citizens and levels of social trust. Shared moral beliefs may in this way facilitate the creation of “moral communities” (Traunmüller 2011). Interpersonal trust in itself may also contain a moral dimension where it is considered as a moral imperative to trust others even though one has no real evidence of the trustworthiness of others (Uslaner 2002). In a related argument, Luhmann (2000) has argued that religion and religious codes of behavior reduce uncertainty in human relations. With less uncertainty in human relations theoretically, this would encourage social trust.

Perhaps not surprisingly most of the literature that delves into the role of religion in Western countries has been focused in the USA. Churches and other faith-based organizations have been central in the formation of both American civil society and the writing of the constitution of the Republic. Diverging radically from the European norm, where the principle one state, one nation, and one religion came to dominate, the American revolution and its subsequent constitution was based on the ideas of religious pluralism and a strict separation between state and church. Furthermore, a general suspicion of state power went hand in hand with civil society institutions – and especially faith-based organizations – playing a central role in building and running schools, universities, hospitals, charities, and other institutions that provided services that in Europe and especially the Nordic countries were provided by the state.

For these and other reasons, American sociologists of religion, public intellectuals, and politicians have for a long time argued that faith-based organizations and individual religiosity play an important role as the social glue that has bound together American society, balancing the forces of egoism that characterized American capitalism. Against the spectre of narcissistic individualism, political polarization, and the decline of social trust in the USA that has been measured since the 1950s, religion is often held up as the “habits of the heart” (Bellah et al. 1985) that has held such tendencies at bay. Robert Bellah, Peter Berger, Alan Wolfe, Robert Wuthnow, and Robert Putnam, all leading academic and public intellectuals in the USA, have in a number of important and influential books pointed to the central role of religion in fostering a sense of community by promoting social trust, charitable giving, volunteering, and civic responsibility.

In a recent ambitious study, based on large national surveys (“the Faith Matters” surveys), Putnam and Campbell (2010) again appear to show that religiosity is correlated with social virtues like trust, trustworthiness, giving, volunteering, and civic mindedness. At the same time they are also careful to note that religion divides as well as unites Americans. The division is both one between those who are religious and belong to congregations and those who are secular or at least stand apart from organized religion and between different religions. Furthermore, while they, generally speaking, see religion as a positive force for social cohesion, they also note that hard-core fundamentalists tend to stand out as more intolerant and less inclusive.

Here Putnam and Campbell echo others who have emphasized both differences between different religious traditions and variation within these traditions. Thus, earlier works by scholars such as Schoenfeld (1978) have suggested that a certain type of fundamentalist religiosity is negative for social trust. Fundamentalist religiosity often tends to emphasize the sinful character of human beings and how the surrounding world, outside the own religious group, is hostile. Schoenfeld (1978) therefore argues that those who belong to fundamentalist-type religious group tend to trust those who are members of the own religious congregation, while they, in general, tend to distrust those outside their own religious group. Uslaner (2001) has also found that fundamentalists are less likely to trust others outside their own religious group and that their volunteering in civil society is more often restricted to groups of people that are similar to themselves. A fundamentalist type of religiosity is more connected to particularized trust or trust in people that is similar than trust towards people in general (Uslaner 2001).

Recent studies using cross-country comparative data paint a picture that at least superficially differs from the one that has emerged from American data. Instead of showing positive correlations these studies instead point to negative correlations between religiosity and social trust (Berggren and Bjørnskov 2011; Wollebaek and Selle 2007). But on closer view these findings appear to call out for further scrutiny. In a study on individual level religiosity and civic engagement in Norway by Stromsnes (2008), she finds that those who often attend church tend to be more politically active as well and that churchgoers at the individual level tend to be slightly more trusting. Even if the relationship between religious involvement and trust, after taking into account socioeconomic and demographic variables, emerges as quite modest, it, on the other hand, gives scant support for the notion that the relationship is a negative one.

However, the emphasis on church attendance and political engagement involves, in fact, a shift away from a concern with sheer belief towards the rather different emphasis on religion as a social practice and on faith-based communities as forms of social organization, a matter to which we will now turn.

6.2.1 Religion as Social Organization

The question of whether it is religion as social organization and participation in church-related activities that matters most for trust is, perhaps, of a more recent pedigree and linked to the massive literature on “civil society” and “social capital” that has developed since the 1990s. Following Coleman (1990) and Putnam (1993), it has been argued that participation in organizations helps to create or maintain social capital. How this actually happens is not always clear, but one argument is that it occurs through mutually reinforcing processes of cooperation and social control, which sanction free-rider behavior and reward social virtue (see, e.g., Wollebaek and Stromsnes 2008).

This suggested connection between participation in organizations, and trust in others has, however, also been questioned (Hooghe 2003; Wollebaek and Selle 2002; Rothstein 2005; Uslaner 2002). It is argued that those who join organizations engage in a process of self-selection, whereby individuals who already are more trusting than others join other high trusters (Newton 1999). However, many empirical studies of the relation between civil society participation and trust have rested on survey data from national level samples where individuals are treated as atoms and are disconnected from their social context. A central claim of the first writings of Putnam (1993) was that social capital, which also contains the concept of interpersonal trust, is a group or even community level asset. If organizational involvement is measured only at the individual level, one may miss the community level aspect (cf. Wollebaek and Stromsnes 2008).

Following that logic, religion and religiosity can also be regarded as a group phenomenon in which religion not only join devout people in religious ceremonies but also bring less practicing followers together under a common set of norms and values. If there is a high level of church attendance at the community level, this could therefore have an impact on social trust in several different ways. High levels of church attendance (just as attendance in other civil society organizations) create dense social networks. It has been argued that if these social networks become sufficiently extensive, they become a public good, and therefore, even those who do not attend church would benefit from these social networks (Granovetter 1973; Putnam 1993). The social networks can function as sources of transferred trust (“if A trusts B and B trusts C then A can also trust C”) (Coleman 1990; Hardin 1993). They can also function as institutionalized forms of cooperation and reciprocity where a noncooperative (or not trustworthy) behavior is sanctioned. A behavior that breaches the trust granted is less likely to pass unnoticed in a society with dense social ties, effectively creating social trust as well as promoting integration and social control. The social networks would in this way function as institutions of social control, and church attendance would then be important mostly at the community level, as the social networks constitute a collective good more than an individual asset.

The study by Putnam and Campbell (2010) also underlined the importance of social networks. In their study what seemed to matter for having less negative attitudes towards those with a different religion is having a diversified social network and to actually have friends from different religions (cf. Marschall and Stolle 2004). There is of course a question of endogeneity associated with trust in strangers and diverse social networks, do people have diverse social networks because they already are more trusting of strangers or do they become more trusting because of the diversity of their social networks? Putnam and Campbell (2010) argue that the increased contacts between different religious groups in the USA seemed to increase trust between these groups.

With respect to Sweden, qualitative studies in areas with relatively high levels of church attendance show that the social networks and connections created through church-related activities were used more broadly, for example, as contacts used for business purposes, and that they also exercised strong social control (Frykman and Hansen 2009; Wigren 2003). Thus the church, even in these relatively secularized communities, still appears to play an important role in creating and maintaining social networks. This is a matter we will pursue and test further below.

6.2.2 Lutheranism Secularized: The Case of Sweden

To analyze the role of religion in the Nordic countries is not an easy matter. While these countries are among the most secularized in the world, this does not mean that the Lutheran legacy is without impact today, albeit in a secularized form, nor that the church as a social institution is of no importance. The Lutheran legacy can also be understood at different levels. For one, the secular moral values associated with the modern welfare state, such as a stress on individual autonomy, equality, and social solidarity, are quite consistent with Lutheran dogma and morality. At another level it is also clear that the (Lutheran) emphasis on a legitimate, positive, and dominant role of the state, on the one hand, and universal literacy (in order that all individuals would be able to read the bible), on the other, have had long-term effects of social structure and political culture, fostering both social trust, confidence in institutions, and an emphasis on individual autonomy and responsibility. In other words, it is difficult to separate out the influence of Lutheranism from its secular successor ideologies, including Social Democracy or, for that matter, a modern market society based on radical individualization and the rule of law.

At a more concrete level it has already been noted above that qualitative studies indicate the importance of the church in shaping the local social networks (Frykman and Hansen 2009; Wigren 2003; Aronsson 2002). One way to proceed is to consider both religiosity and secularism in terms of both dogma and belief and as a social practice. That means separating out, as a matter of both analysis and operationalization, religion as dogma and belief and religion as a social organization and practice. And it should be noted that the same can be done with secularism, on the one hand looking at secular forms of association in civil society that enhance trust and foster social and civic virtues, on the other considering a more dogmatic form of secularism that is aggressively atheist and also incorporates a view of human nature closer to classical economic theory with its atomistic individualism according to which, as Margret Thatcher famously claimed, “there is no such thing as society.”

These are grand questions: here our ambition is more modest, namely, to tease out analytically and capture in operational terms what we see as two different dimensions of religion. We now turn to that task.

6.2.3 Hypotheses

We have chosen to formulate different hypotheses regarding the effects of the intensity of religiosity as theology and faith, on the one hand, and religious involvement as a social network, on the other hand. As noted above, it has been argued that religious activities mainly tend to foster in-group trust rather than trust towards strangers (Schoenfeld 1978). Distrust in strangers is more connected to being active within more fundamentalist-type religions because the sinful and untrustworthy nature of mankind is often underlined within these groups (Schoenfeld 1978). On the other hand a view of religion that stresses the love of mankind may work the opposite way underlining the importance of doing good things and is therefore encouraging trust in others.

The first set of hypotheses concerns religion as faith and dogma and if it matters for trust:

-

(1a)

Religious salience in life correlates negatively with generalized trust.

-

(1b)

Individual religious participation correlates negatively with generalized trust.

-

(1c)

A view on religion as doing good things correlates positively with generalized trust.

-

(1d)

A dogmatic view on religion correlates negatively with generalized trust.

The second set of questions revolves around whether religion as social organization and social networks correlates with trust. This could be interpreted as the civil society aspect of religion:

-

(2a)

Church attendance at the community level correlates positively with generalized trust.

-

(2b)

Volunteering for a parish or a religious congregation correlates positively with generalized trust.

6.3 Methodological Considerations

One of the main criticisms against cross-country comparative studies is that institutional and other contextual differences are confounded with the effects of the studied variables (Traunmüller 2011). In other words it is often difficult to disentangle whether other variables that express country level differences that are omitted may better explain the differences between countries. A possible way round the problem of spurious relationships due to variables that are not included in the models up is to try and keep as many as possible of the background variables constant. Arend Lijphart (1971) and others (Przeworski and Teune 1970) have proposed the use of most similar systems design in comparative studies. In our case this is achieved through the study of different local communities within a single country. By doing so we keep the institutional context constant. Traunmüller (2011) has carried out a similar within-country comparative study on Germany.

As a measurement of social trust we chose to use several different survey items related to trust rather than rely on the single generalized trust question.Footnote 2 The survey items that are used are: generally speaking most people can be trusted; you ought to trust people even if you have no proof of their trustworthiness; it is right to trust people even if you don’t know them too well. We use the factor scores of the three survey items multiplied by 100 in order to get more readable regression coefficients. For the wording of the survey items used, please see Table 6.1.

How to methodologically define religiosity is often a debated issue (Putnam and Campbell 2010). In other studies a distinction between religious belief and religious practice has been made (Halman and Draulans 2006; Putnam and Campbell 2010). We opt to use both individual level measurements and community level measurements to express religiosity as belief and religious practice. At the individual level we use measurement of the saliency of religion in one’s life, measurements of religious participation, and measurements reflecting the scope of religion.

Different from most other surveys we have the possibility to include variables expressing religiosity at the community level that are not derived from the survey answers. Sweden also has an excellent source of aggregate level statistics related to Lutheran religiosity as the Lutheran Church of Sweden keeps statistics on, e.g., church attendance and membership rates. Church attendance varies across the investigated municipalities. At the local community (aggregate) level we use a measurement reflecting church attendance. In addition we also use a measurement expressing community level church membership, it could however be disputable to which extent it is a measurement of religiosity as membership in the church was so pervasive during the period that it was still a state church. Church attendance is correlated, although not very strongly, at the aggregate level with the proportion of church-affiliated citizens in the municipality (Pearson’s r = 0.29, p < 0.00). Just using the degree of religious affiliation may therefore not be a good measurement of religiosity in the case of Sweden.Footnote 3

We use data from a survey carried out in 2009 in Sweden with a representative sample of citizens in 33 different municipalities. In order to achieve variance at the contextual (community) level variables, we created a quasi-experimental design. The municipalities were first grouped in 16 different subgroups according to variation in contextual level variables (among which official rates of church attendance) and then randomly drawn (two from each group) into the survey.Footnote 4 In a second stage the representative sample of citizens in each municipality was drawn. The survey was carried out by Statistics Sweden. The overall response rate was 51.2 %, and due to internal missing values, the valid observations decrease, and the total number of respondents used in the analyses below is 3,658. Given the nested structure of the sample multilevel modeling is the most appropriate method of analysis (Hox 2002).

6.4 Results

In order to analyze the Swedish data we use multilevel modeling statistics. One of the advantages of multilevel modeling techniques is that we can model the effects both from individual level data and context (community) level data. We can therefore model whether there are any effects from the community level church attendance on individual level trust.

In the empty model the amount of variance explained at the community (contextual) level is statistically significant, implying that a small amount of the variance in individual levels of trust is coming from the variance in community level factors. Approximately 1.2 % of the variance of individual levels of trust is explained by community (contextual) level variables. This also implies that 98.8 % of the variance is explained by variance in individual level variables. We construct a model including variables that express the different aspects of religiosity and a set of control variables. We add the proportion of the foreign population as a control variable since it is less likely that residents (even from neighboring Nordic countries) born abroad are members of the Church of Sweden (cf. Stolle et al. 2008). We also add community population size as a control variable to check whether or not community size influences individual levels of trust. If religious practice is more connected to small and less urbanized communities, then this variable ought to become statistically significant. We also add intensity of religious practice (church attendance) both at the individual and the community level without considering the importance of religion in life. Furthermore we add items expressing the scope of religion (following rules and religious ceremonies and religion as doing good things to others) (Table 6.2).

In the full model where both the individual and the contextual level variables are added, the overall fit of the model increases (this could be observed from how both the deviance and the BIC values decrease). However, the variable expressing the importance of religion in life is not statistically significant, and neither is the variable measuring individual level church attendance. The saliency and the practice hypotheses (1a and 1b) at the individual level thus find no support in the data. The individual level variables connected to religiosity that are statistically significant and positively correlated with trust in others are being a member of a religious congregation and having a view of religion as doing good things for others (1c). (It is, however, not entirely uncomplicated under which aspect of we can place the membership variable in the case of Sweden given the character of the historical monolithic state church where all citizens were members.) The item expressing the view on religion as following dogma and devoutly participating in religious ceremonies is negatively correlated with trust in others, which is also in line with expectations (1d).

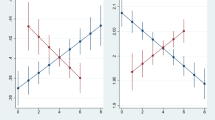

At the municipal level church attendance is positively correlated with individual levels of trust and statistically significant at the 5 % level. This is in line with the expectations of religious participation as creating social networks (2a). Volunteering for a parish/religious congregation is also positively related to trust in others (2b). The figure below shows the marginal effects from volunteering on predicted levels of trust (all other variables kept at their mean value). The predicted value on the trust scale is about 23 units higher for someone who volunteers for a parish or another religious congregation than for those who don’t (Fig. 6.1).

The community population size is not statistically significant in any of the models, which indicates that religiosity is not solely an expression of being a small and hence more rural community. The levels of education at the community level are however statistically significant, and the results indicate that the higher the proportion of inhabitants with low levels of education are, the lower the individual levels of trust become. It is well known from previous studies that education plays an important role in explaining levels of trust (Fig. 6.2).

The graph below shows the marginal effects (keeping all other variables constant at their mean value) from community level church attendance and predicted individual levels of trust.

The illustrations show that the increase on individual levels of trust from community level church attendance. An individual living in a community within the 10th percentile of lowest levels of church attendance has a predicted trust score equaling 2, while an individual living in a community with the highest level of church attendance has a predicted trust score equaling 11, all other things equal. This is quite a modest increase, albeit statistically significant, given that the trust score varies from approximately −250 to 200. The figure also shows that the increase is sharper at the top end (above the 50th percentile) of the distribution of the church attendance than at the bottom end. This suggests that the attendance needs to be sufficiently high in order to have more tangible effects on the individual levels of trust.

6.5 Discussion and Conclusion

We started this chapter by presenting two seemingly different aspects of the supposed causal mechanisms behind how religion as social organization and religiosity as belief may influence trust. We argued that it is important to distinguish between these two different aspects and to combine community and individual level data in order to be able to test context effects. The first finding is that religiosity in general has some impact on individual level trust even in a relatively secularized country like Sweden. The religiosity and religious practice variables that were significantly correlated with trust in others were more related to the social organization aspects of religion rather than religion as saliency in life or individual level practice. Neither individual level importance of religion in life nor individual level church attendance correlated significantly with trust in others.

Trust is, on the other hand, positively related with having a moral or philanthropic view on religion (Uslaner 2002; Traunmüller 2011). That is to say, the internalization of moral codes founded in religious belief may be a factor in explaining why people trust even if they have no real evidence of the trustworthiness of the other person. Believing that it is good to trust others is positively associated with having a religious belief in the sense of thinking that religion is about doing good things for others and being active as a volunteer in a parish. The positive correlation between volunteering and trust confirms results from previous studies on the relationship between volunteering and trust (Putnam 1993; Putnam and Campbell 2010). It is difficult to disentangle through survey research whether having a view on trust as something normatively good actually corresponds with a more trusting behavior.

The social organization hypothesis, is at least partially, confirmed through the positive relationship between community level church attendance and trust. Church attendance seems to have an effect only as a collective phenomenon, while it has not any significant effect on trust at the individual level. Someone could attend the church each and every day, but it does not seem to have the same effect on trust as the community level church attendance. It strengthens view of social participation (social networks) as a collective or group asset. The interpretation of the community level church attendance could be twofold either that the social networks restrain opportunistic (untrustworthy) behavior or that it encourages trustworthy behavior (cf. Putnam 1993). More qualitative studies in Swedish communities with high levels of church attendance have shown that the social networks in these areas are dense and extensively used (also for social control) (Frykman and Hansen 2009; Aronsson et al. 2002). The conclusion therefore is that religion as social organization seems to matter for individual levels of trust, while the role of theology or religious beliefs is not confirmed in the data.

The broader implication of these findings is that, in so far as our focus is on trust and social cohesion, we may be better off to see the role of religion from a social network or civil society organization perspective rather than in terms of dogma and belief. On this reading, congregations are one part of the associational life that taken together connect and socialize individuals in a climate of trust. To be sure, this does not mean that values – as opposed to practices – are not important. As noted above, religious belief in the sense of thinking that religion is about doing good things for others and being active as a volunteer in a parish does appear to correlate with trust. The point is rather that such values are general and open enough not to exclude others but instead function as a bridge between secular and religious society.

This takes us back to the larger question of how the specific religious inflection that is dominant in Sweden – Lutheranism – has shaped and continues to shape social, political, and economic life in modern Sweden. Pace Weber, it is hard not to see the linkages between Lutheran values and practices, with an emphasis on the individual, the state and the law, and those that seem to be the paradoxical hallmark of modern Sweden: a radical individualism joined to high levels of social trust and the rule of law (Berggren and Trägårdh 2010).

Notes

- 1.

Although social trust is a complex theoretical concept, it has very often been measured through a single survey item, and it has been discussed whether this single item accurately picks up the complexity (Van Deth 2003). In this chapter we will rely upon several different items that measure trust as a moral imperative.

- 2.

See note 1 on the problems associated with the classical single trust question first used by Rosenberg.

- 3.

This is mainly due to the already mentioned history of Sweden having had a state church with the citizens being members of the church until they explicitly left it.

- 4.

With the addition of the municipality of Malmö.

References

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Aronsson, P. (2002). Tillit eller misstro i småorternas land – en studie av social ekonomi i fem län. Växjö: Växjö University.

Aronsson, P., Betranz, L., Hansen, J., Johansson, L., Lärstedt, C., & Olofsson, G. (2002). Tillit och misstro i småorternas land, en studie av social ekonomi i fem län. Växjö: Växjö universitet.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. New Delhi: Sage.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Berggren, N., & Bjørnskov, C. (2011). Is the importance of religion in daily life related to social trust? Cross-country and cross-state comparisons. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 80(3), 459–480. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2011.05.002.

Berggren, H., & Trägårdh, L. (2010). Social trust and radical individualism: The paradox at the heart of Nordic capitalism in The Nordic Way. Stockholm: Global Utmaning.

Bok, S. (1978). Lying: Moral choices in public and private life. New York: Pantheon Books.

Bordum, A. (2001). Tillit er godt! Om tillidsbegrebebets vaerdiladning. In A. Bordum & W. Barlebo (Eds.), Det handler om Tillid. Frederiksberg: Samfundslitteratur.

Coleman, J. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Delhey, J., & Newton, K. (2005). Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: A global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review, 21(4), 311–327.

Frykman, J., & Hansen, K. (2009). I ohälsans tid: sjukskrivningar och kulturmönster i det samtida Sverige. Stockholm: Carlssons förlag.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. The American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Halman, L., & Draulans, V. (2006). How secular is Europe? The British Journal of Sociology, 57(2), 263–288.

Hardin, R. (1993). The street-level epistemology of trust. Politics and Society, 21(4), 505–529.

Hardin, R. (1999). Do we want trust in government? In M. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hooghe, M. (2003). Participation in voluntary associations and value indicators: The effect of current and previous participation experiences. Non Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32(1), 47–69.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis. Mahwah/London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Lasch, C. (1979). The culture of narcissism: American life in an age of diminishing expectations. New York: Norton.

Lijphart, A. (1971). Comparative politics and the comparative method. American Political Science Review, 65(3), 682–693.

Luhmann, N. (2000). Familarity, confidence, trust: Problems and alternatives. In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 94–107). Oxford: Department of Sociology, University of Oxford.

Marschall, M., & Stolle, D. (2004). Race and the city. Political Behavior, 26(2), 125–153.

Misztal, B. (1996). Trust in modern societies: The search for the bases of social order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Newton, K. (1999). Social capital and democracy in Europe. In J. van Deth, M. Maraffi, K. Netwon, & P. Whiteley (Eds.), Social capital and European democracy (pp. 3–24). London/New York: Routledge/ECPR Studies in European Political Science.

Patterson, O. (1999). Liberty against the democratic state: On the historical and contemporary sources of American distrust. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, A., & Teune, H. (1970). The logic of comparative social inquiry. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Putnam, R., & Campbell, D. (2010). American grace. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Riesman, D. (1950). The lonely crowd. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2005). Social traps and the problems of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schoenfeld, E. (1978). Image of man: The effect of religion on trust. Review of Religious Research, 20(1), 61–67.

Seligman, A. (1997). The problem of trust. New York: Free Press.

Simmel, G. (1950). The sociology of Georg Simmel. New York: Free Press.

Stolle, D., Soroka, S., & Johnston, R. (2008). When does diversity erode trust? Political Studies, 56(1), 57–75.

Stromsnes, K. (2008). The importance of church attendance and membership of religious voluntary organizations for the formation of social capital. Social Compass, 55(4), 478–496.

Sztompka, P. (1999). Trust. A sociological theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Traunmüller, R. (2011). Moral communities? Religion as a source of social trust in a multilevel analysis of 97 German regions. European Sociological Review, 27(3), 346–363.

Uslaner, E. (2001). Volunteering and social capital: How trust and religion shape civic participation in the United States. In P. Dekker & E. Uslaner (Eds.), Social capital and participation in everyday life (pp. 104–117). London/New York: Routledge.

Uslaner, E. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Deth, J. (2003). Measuring social capital: Orthodoxies and continuing controversies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(1), 79–92.

Wigren, C. (2003). The spirit of Gnosjö: The grand narrative and beyond (Dissertation series: 17). Jönköping: Internationella Handelshögskolan.

Wollebaek, D., & Selle, P. (2002). Does participation in voluntary associations contribute to social capital? The impact of intensity, scope, and type. Non Profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31(1), 32–61.

Wollebaek, D., & Selle, P. (2007). Origins of social capital: Socialization and institutionalization approaches compared. Journal of Civil Society, 3(1), 1–25.

Wollebaek, D., & Stromsnes, K. (2008). Voluntary associations, trust, and civic engagement: A multilevel approach. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37(2), 249–263.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lundåsen, S.W., Trägårdh, L. (2013). Social Trust and Religion in Sweden: Theological Belief Versus Social Organization. In: de Hart, J., Dekker, P., Halman, L. (eds) Religion and Civil Society in Europe. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6815-4_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6815-4_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-6814-7

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-6815-4

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)