Abstract

Early childbearing, especially as an adolescent, has been labeled by one former president as the country’s “most important social problem” (Clinton 1995). Conventional wisdom suggests that having a child as a teenager is detrimental for maternal well-being, especially educational attainment and labor market outcomes, but also for interpersonal outcomes, such as relationship quality with partners and exposure to intimate violence. Many studies confirm such expectations (see Hayes 1987). Empirically, teenage childbearing has been linked to lower levels of completed education (Hotz et al. 1997; Fletcher and Wolfe 2009), lower wages and earnings and generally worse labor market outcomes (Chevalier and Viitanen 2003; Klepinger et al. 1999), and lower rates of marriage and higher overall fertility (Bennett et al. 1995; Hoffman et al. 1993), although some studies have suggested the negative economic and social consequences of teen pregnancy and childbearing are not as large as once thought (Furstenberg 1991; Lawlor and Shaw 2002; Scally 2002; Rich-Edwards 2002).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Early childbearing, especially as an adolescent, has been labeled by one former president as the country’s “most important social problem” (Clinton 1995). Conventional wisdom suggests that having a child as a teenager is detrimental for maternal well-being, especially educational attainment and labor market outcomes, but also for interpersonal outcomes, such as relationship quality with partners and exposure to intimate violence. Many studies confirm such expectations (see Hayes 1987). Empirically, teenage childbearing has been linked to lower levels of completed education (Hotz et al. 1997; Fletcher and Wolfe 2009), lower wages and earnings and generally worse labor market outcomes (Chevalier and Viitanen 2003; Klepinger et al. 1999), and lower rates of marriage and higher overall fertility (Bennett et al. 1995; Hoffman et al. 1993), although some studies have suggested the negative economic and social consequences of teen pregnancy and childbearing are not as large as once thought (Furstenberg 1991; Lawlor and Shaw 2002; Scally 2002; Rich-Edwards 2002).

Even more noteworthy than these negative consequences, however, are the race/ethnic disparities that surround teenage births. In 2007, the live birth rate per 1,000 teens aged 15–19 was 27.2 among white youths but 64.2 among African American youths and 81.7 among Hispanic youths (Hamilton et al. 2009).Footnote 1 These race/ethnic differences are also apparent among even younger teens between the ages of 10 and 14. Thus, while it is important to study early childbearing because of its potential life-long negative consequences for women, it is also important to study because of its implications for the intergenerational reproduction of race/ethnic inequality and disparities in health and well-being.

Much of the research seeking to account for race/ethnic differences in teenage childbearing focuses on family-related factors, such as socioeconomic status. One explanation that has captured the attention of social scientists is the weathering hypothesis (Geronimus 1991). Weathering refers to the physical consequences of social inequality. Specifically, it states that minority women (as well as men) who live in poverty experience early physical deterioration, relative to more advantaged women, because of the biological and social processes associated with poverty and racism. The weathering hypothesis, as it pertains to teenage childbearing (Burton 1990; Geronimus 1991, 1992b, 1996, 2001), suggests that early teen pregnancy and childbearing is rational for many socioeconomically disadvantaged American women if they believe that they will likely age more quickly than other women and have shortened life spans. Early childbearing thus may represent a more normative act among certain segments of the population based on the poor health status of surrounding adults. The young women in these communities may believe that peak reproductive years should shift to earlier stages in the life course given the rapid aging they perceive.

We propose a simple yet, to date, unexplored test of the basic assumption of the weathering hypothesis at a basic ecological level: does an adolescent’s mother’s health status predict her odds of experiencing pregnancy and childbirth at a young age? If the weathering hypothesis is correct, we would expect that poor maternal health, as a proxy for an adolescent girl’s expected health status in adulthood, and teen childbearing are positively correlated among African American and Hispanic youths, but not among white teens. Using a subsample of young women from the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (PSID) we explore how maternal self-rated health when a young woman is age 14 is associated with her odds of experiencing a pregnancy before age 19, controlling for other individual, maternal, and family level characteristics.

Background

Race/Ethnic Differences in Health

Race/ethnic differences in health are well-documented (Dressler et al. 2005; Geronimus et al. 2001; Wong et al. 2002). For example, Geronimus and Thompson (2004) estimate that in central Harlem and the south side of Chicago, black adults are as or more likely to suffer health-induced functional limitations at age 34 as are 55-year-old whites nationwide; they also find that disability rates among 55-year-old blacks approximate those of 75-year-old whites and that only 30% of teenage African American girls and 20% of African American boys can expect to be alive and able-bodied at age 65. The corresponding figures for whites nationwide are 70 and 60%, respectively.

The weathering hypothesis has been invoked to explain such race/ethnic differences in health status. In particular, the thesis is that African Americans have higher allostatic load, or physiological responses to chronic stress (McEwen 2000) due to characteristics such as poverty, economic hardships, and racism (Geronimus et al. 2006, 2007; Williams 1999). Allostatic load is linked to a “wearing down” (or weathering) of the body’s cardiovascular system and ability to fight off disease and illness (McEwen 1998). Evidence links increased stress with chronic diseases, such as hypertension, one of the major contributors to excess mortality among urban blacks (relative to whites) (Geronimus et al. 1996; Geronimus and Thompson 2004; Williams 1999; Williams and Jackson 2005).

With increasing age, the minority gap in health widens as the deleterious effect of cumulative stress exposure takes it toll (Clark and Maddox 1992; Shuey and Willson 2008). Among many minorities, disease, illness, functional limitations, and disabilities are already present by the mid 1920s and early 1930s and rates rise through the 1940s and 1950s (Geronimus et al. 2006). The weathering hypothesis suggests that it is this pervasive health uncertainty that women of childbearing and working age face that is responsible for higher birth rates at younger ages among African Americans. Or as Lancaster et al. (2008) suggest, “weathering is a formidable threat to family economies and caretaking systems” (p. xx). Chronic diseases also complicate pregnancy (e.g., hypertension and diabetes) resulting in an increased number of babies born prematurely, with low birth weight, or who will die before they reach the first year of life (Gilbert et al. 2007; Rosenberg et al. 2005). Thus, having a child early, while still healthy and physically robust, is seen as a positive life event. In the same Harlem sample mentioned above, infant mortality rates among teen mothers were roughly half of what they were for older mothers, who were still in their 1920s (Geronimus 2003).

Weathering and Early Childbearing

Geronimus (1992b, 1996) first reported the paradoxical finding that birth outcomes, such as birth weight, among teen black mothers were better than among older black mothers. For white women, the reverse was true: white women in their 1920s always had better infant health outcomes than white women in their teens. She went on to argue that health deterioration among race/ethnic minorities occurred more rapidly than among whites, given greater cumulative exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage, discrimination, and other structural constraints that result in harsh environments. Her weathering hypothesis postulates that age patterns at birth are an adaptive response to the life conditions that each group experiences and represent women’s efforts to take advantage of an optimal age at birth, with black births occurring, on average, earlier than white births.

Wildsmith (2002) suggests that there are two ways to test the weathering hypothesis: (1) by comparing age-specific patterns of health outcomes between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged groups, and (2) by examining within-group variations of these outcomes across age. Using the first strategy, Geronimus (1992b) examined black-white differences in infant survival and found that black infants had the greatest survival advantage at younger maternal ages whereas white infants have the greatest survival advantage at older ages (see also Ananth et al. 2001; Rich-Edwards et al. 2003). More generally, Geronimus’ work has sought to test the weathering hypothesis by seeing whether black women, relative to white women, have worse health during the child bearing years (see Geronimus and Bound 1990; Geronimus et al. 1991b, a; Geronimus and Hillemeier 1992; Geronimus et al. 2007). Using the second strategy, Wildsmith (2002) examined Mexican-origin women, both native and U.S. born, and found some support for the weathering hypothesis. Among U.S. born women, rates of neonatal mortality and hypertension showed a curvilinear relationship with age, reaching the lowest levels between 17 and 18.

As noted above, existing empirical tests of the weathering hypothesis have focused on race/ethnic differences in maternal and infant health outcomes. When more positive health outcomes (e.g., neonatal mortality, birth weight, etc.) are observed among younger disadvantaged sample members, authors typically conclude that they have found support for the weathering hypothesis. We argue, however, that this is not a complete test of the weathering hypothesis. With respect to teenage childbearing, the weathering hypothesis has two components, one explicit and one more implicit. First, the theory explicitly states that blacks and other race/ethnic minorities have worse and more rapidly deteriorating health status compared to whites given differential cumulative exposure to all sorts of structural factors (e.g., poverty, discrimination, violence). Second, and more implicit in the theory, minority teens use the world around them to make assessments about own future health and mortality (see Geronimus 1992a; Geronimus et al. 1999). Such social construction is likely to be based on the physical health of the adults closest to them (i.e., family and community members). In a qualitative study of a black community in the northeast, Burton (1990) finds evidence of what she calls an accelerated family time table. She notes that, “…the community is so homogenous and close-knit that individuals often interpreted their life-course possibilities in light of what happened to individuals around them” (p. 132). She goes on to report that many women, including teenagers, were extremely cognizant of community mortality patterns suggesting the very real possibility of an early death. Many of these women aspired to have children early not only to maximize their own reproductive success but also to allow their own mother, or even grandmother, to take part in the child’s life.

Despite the implied importance of intergenerational health for the weathering hypothesis this piece of the theory has never been empirically tested. Geronimus and colleagues (1999) examined the probability that a child’s parents or grandparents would live to see the child’s 20th birthday across a number of urban U.S. areas and found that blacks were less likely than whites to have family members who survived to the end of the interval and the discrepancy grew as age at birth increased. Although the findings support the first component of the theory, the analysis falls short of explicitly testing whether adult health has a direct impact on teen childbearing decisions and thus does not test the second component of the theory outlined above. We argue that the most theoretically grounded test of the weathering hypothesis with respect to teenage childbearing should focus on the association between adult health and teen pregnancy/childbirth, specifically focusing on the lineage of maternal health status. According to the theory, teens with parents, especially mothers, who are in poor health should have higher odds of teen pregnancy and childbirth. Because health status is likely to vary by race/ethnicity and class, it will be important to test the association between maternal health and teenage childbearing across these dimensions.

Learning Theories and Early Childbearing

Two social psychological theories, derived from learning theory, further suggest that minority adolescents and young adults may use parental health status as a basis for their own fertility intentions: social cognitive theory and the theory of planned action. Both posit that individuals construct new knowledge from their experiences in the social world (Bandura 1977). Social cognitive theory (SCT) explains how people acquire and maintain certain behaviors, while also providing a rationale for intervention strategies (Bandura 1989, 1997). It describes learning in terms of the relationships between behavior, environmental factors, and personal factors (e.g., cognitions, affect, or biological events). Knowledge is gained through experiencing the interplay of these elements of life, and new experiences are evaluated with respect to past experiences such that they help individuals to determine what their own actions will be across a range of situations. In other words, SCT is a learning theory based on the idea that people base their own behavior on the behavior and experiences of others around them (Miller and Dollard 1941). Ultimately the individual comes to believe that certain things will happen because he or she observes them happening to others around him or her, and this element of the theory relies heavily on outcome expectancies. These expectancies are greatly influenced by the individual’s environment and for teenagers the family serves as one of the primary environments from which these expectancies are formed.

As previously mentioned, there are large health discrepancies among African American and white adults and these differences are not restricted to objective measures of health status like chronic disease (National Center for Health Statistics 2009), disability (Kelley-Moore and Ferraro 2004), life expectancy (Harper et al. 2007), and mortality (Satcher et al. 2005). Age- and sex-adjusted estimates from the 2008 National Health Interview Survey show that 69.7% of white adults reported very good or excellent health compared to 58.1% of African American adults (Heyman et al. 2009). The percentage for Latino adults reporting very good or excellent health is even lower at 56.8%. Adjusted regression models suggest that African American adults are roughly twice as likely as whites to report fair or poor SRH (Boardman 2004; Borrell and Crawford 2006; Ferraro 1993). Spencer and colleagues (2009) find that, controlling for physical functioning, older white adults were almost four times as likely as older African American adults to report favorable self-rated health. The authors suggest that health pessimism is stronger among the African American elderly population than whites. These studies suggest that African American youths have a higher rate of exposure to adults in poor physical health. Thus, based on social learning theory, one could argue that this difference in the prevalence of morbidity, mortality, and poor subjective health ratings among adult minorities might also lead to lower expectations about future health status among African American youths compared to white youths.

Building on the concept of expectancies, the theory of planned behavior predicts that beliefs and attitudes (i.e., expectations), shared norms, and perceived behavior indirectly determine actual behavior via behavioral intention (Azjen 1991). Beliefs and values about a certain behavior, and more importantly, its consequences, are evaluated with respect to norms surrounding both behavior and outcome. Individuals also assess how much self-efficacy they have with respect to the behavior. That is, for a behavior to occur individuals must believe they are capable of successfully executing that behavior in order to produce the desired result (Bandura 1977). When self-efficacy is high, the behavior is thought to be normative, and both the behavior and especially the outcome are positively valued, the odds of that behavior actually occurring are increased via heightened behavioral intention (Azjen and Fishbein 1980).

Many of the elements of the theory of planned behavior have been applied to early childbearing, including beliefs about age at first pregnancy, norms about early childbearing, and contraceptive use (see Buhi and Goodson 2007; Myklestad and Rise 2007). For some young women, early age at first pregnancy is not viewed in a negative light, but rather is seen as a way to connect with the child’s father or grow closer to her family, to force adulthood at a time when most teens struggle with forming an identity, or as motivation to work harder in order to support the child (Rosengard et al. 2006). Some scholars, like Geronimus (1991, 2003) and Burton (1990) have argued that early childbearing can be a normative life course event among certain race/ethnic cultures, especially African Americans. A lack of stigma surrounding teenage childbearing (Mollborn 2009; Olson 1980), and the view that having a child early in life offers more benefits than negative consequences, may lead some adolescents and young adults to view childbearing as a positive event. When these conditions co-exist, some teens and young women may participate in behaviors that facilitate their desired outcome. And indeed, some research on early childbearing suggests that inconsistent and infrequent use of contraception is a planned behavior (Brückner et al. 2004; Davies et al. 2006; Jaccard et al. 2003; Rosengard et al. 2004).

Hypotheses

Lancaster and colleagues (2008) note that how ecologies come to influence fertility timing is an understudied question. They suggest that teens and their elders may make conscious fertility decisions without having explicit knowledge of the statistical odds of death, disability, and disease among the African American community. Instead, because these events are pervasive in the culture, poor physical health is assumed to be a biological imperative. Qualitative studies of African Americans suggest that fertility-timing decisions in specific high poverty areas do involve socially derived knowledge of the benefits of early childbearing and multi-generational childrearing (Stack and Burton 1993; Geronimus 1996), but similar empirical evidence is lacking.

Based on social cognitive theory, as well as the theory of planned behavior, we expect that teens and young adults will use the health status of their parents as guides for their own fertility behavior. These theories lead us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

Young women will use their mother’s health status (i.e., maternal self-rated health) to inform pregnancy decisions at early ages.

Along with Geronimus’ weathering hypothesis, the theories reviewed above also make powerful predictions about how race and ethnicity interact with environmental cues. In particular, African American teens may be more likely to witness adults with low levels of physical health, given the combined deleterious effects of socioeconomic disadvantage and racism. If, as suggested by social cognitive theory, these young women derive expectations about their own future health status from the observed health of those around them, especially their mothers, they may come to believe that good health occurs only during a brief period, early in the life course. If they then use those beliefs to make decisions about the sexual behavior and timing of pregnancies, as suggested by the theory of planned behavior, we might expect African American teens to enter into motherhood at an earlier age than teens of other race/ethnic groups.

Our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2:

The association between maternal self-rated health and fertility behavior (i.e., pregnancy and birth) will be stronger among African-American and Hispanic young women than white young women.

Thus, we propose a direct test of the weathering hypothesis that examines whether a teen’s mother’s self-rated health status is associated with increased odds of the teen having a child before the age of 20 and if it is, whether this association is stronger among African American versus Hispanic or white young women.

Method

Data

The dataset used to perform the analyses comes from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a national survey of 5,000 American families first interviewed in 1968. The PSID sample was interviewed every year for the first 20 years and every other year since then. The PSID is an excellent data source for examining the effects of parents’ health status on adolescent children’s fertility because it follows children from the original sample as they have grown into adulthood and formed their own households. Our primary maternal health measure is self-rated health (asked each year since 1984). Although PSID has contained other health items in each wave, health content was not expanded and consistent until the 1990s.

We restrict our analysis to daughters born between 1970 and 1991 who had val.d data when they had reached age 14. This resulted in a sample of 3,588 young women. We dropped four cases where the data indicated that a birth occurred before age 19 but age at first birth information was missing. We dropped an additional case where age at first birth was listed as age six. Finally, we dropped 209 cases where no data were available on maternal characteristics. We did not drop, but excluded, cases where a birth occurred before age 14 (n = 15 cases where a first birth occurred at ages 12 or 13) because we rely on maternal characteristics when the daughter was age 14. Thus we are left with 3,359 young women in our analytic sample.

The first year in which we observe a daughter’s pregnancy or birth outcome is 1984 and the last year in which we observe pregnancy and birth outcomes is 2005, the most recent year for which public use data was available for the analysis. Consequently, the births we observe occur to daughters who were between the ages of 14 and 19 by 1984 and daughters who had reached at least age 14 by 2005. Those who had not yet reached age 14 in 2005 are right-censored.

Measures

Dependent Variable. In the analytic sample, 10.1% had a non-marital birth before age 19 (n = 340, see Table 11.1).Footnote 2 Compared to previous studies using the PSID, this sample includes teens from cohorts in the 1990s, a period in which birth rates fell (Klein and the Committee on Adolescence 2005). The dependent variable in our analysis is time to event, which in this case is age at first non-marital birth through age 19. Young women who had not had a non-marital birth by age 19 were right censored at age 19 and young women who experienced a marital birth prior to age 19 were censored at the age of first marriage (see footnote 1).

Daughter Characteristics. A number of covariates are included in the model based on the fact that existing literature has shown them to be associated with teenage childbearing. Daughter’s race/ethnicity is defined by a series of dichotomous variables for white Non-Hispanic (37.6%), black non-Hispanic (46.4%), Hispanic (13.0%), and other (2.2%), with white as the reference group.

Maternal Characteristics. All maternal characteristics are collected when her daughter was age 14. Maternal self-rated health is a continuous variable ranging from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor) (mean = 2.5, SD = 1.0). Approximately 15% of mothers in the sample were in fair or poor health. Marital status is a series of dichotomous variables indicating that the mother was married (65.0%), divorced/separated (19.6%), widowed (2.0%), or single (11.4%), with married as the reference group. Maternal education is measured in single years of completed schooling (mean = 12.2, SD = 2.7). Maternal employment status is a dichotomous variable indicating that the mother was employed (85.9% were employed). A final dichotomous variable indicates whether the mother herself experienced a teenage birth (30.2%).

Family Characteristics. Family income (in thousands of dollars) in 1984 is included as a measure of overall family socioeconomic status (mean = $33,700, SD = $38,200). We also include (but do not show in the results tables) a flag for missing family income.

Key Independent Variable. An interaction term between maternal self-rated health and daughter’s race/ethnicity is used to assess the predicted race/ethnic difference in the association between maternal health status on daughter’s fertility decisions.

Analysis

Data estimating age at first teen birth are analyzed using a standard Cox proportional hazard model for adolescents of all race and ethnic groups combined. As shown in Eq. 11.1, the hazard at time t, h(t), is defined as the likelihood of giving birth in year t, given that a young woman did not give birth prior to time t or reached age 19 by time t:

The h0(t) term represents the baseline hazard at time t for an individual i who has a 0 on all of the predictor variables in the model. The βkxik term includes the covariates, or predictor variables, included in the model. Positive coefficient estimates for the predictor variables indicate that higher levels of the variable increase the hazard of an early birth. Negative coefficients have the opposite interpretation. The inverse logarithm of the estimated coefficients is interpreted as the risk ratio. A risk ratio greater than one indicates a higher risk of early childbearing for women with higher levels of the variable compared to women with lower levels.

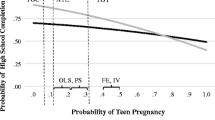

To test Hypothesis 1 we investigate whether there is a significant first-order, bivariate association between maternal self-rated health and fertility outcomes among young women without including any of the covariates. Stage two of this model includes the covariates described above, including the daughter’s race/ethnicity. Stage three of this model includes interaction terms between race/ethnicity and maternal self-rated health to investigate Hypothesis 2. Based on the joint significance of these interaction terms with all predictors in the model (p < 0.0001), we present separate models for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic groups to compare the effects of the covariates on early childbirth across the three groups.

We use multiple imputation to replace missing values in five simulated versions (Rubin 1987). The simulated complete dataset is analyzed by standard methods and the results are combined using the “micombine” command in STATA 10.1 (see Royston 2005). (Descriptive statistics for the imputed sample can be found in Table A.1.) Observations for daughters within the same family are not independent. Therefore, we correct all standard errors and p-values for the complex (clustered) data structure that would be miscalculated in a standard survival time analysis.

Results

Table 11.1 presents descriptive statistics for the non-imputed analytic sample. Not surprisingly, rates of early childbearing are higher among non-Hispanic blacks than non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, or other race/ethnicities (p < .0001 level, significance not shown in the table). Mothers of white young women rate themselves as healthier than other mothers (p < .0001). In general, white young women are more advantaged than their minority peers in terms of maternal characteristics, including marital status, education, and employment status, as well as family income. Finally, significantly fewer white young women have a mother who herself experienced first birth before the age of 19 than young black, Hispanic, or other race/ethnic women (p < .0001 for black and Hispanic; p < 05 for other).

Recall that our first hypothesis predicted that young women would use their mother’s health status, defined as self-rated health, to inform pregnancy decisions at early ages.

To test this hypothesis we estimate the association between the characteristics of daughters and mothers when daughters are age 14 and time until first teen non-marital birth (see Table 11.2). Model 1 in Table 11.2 shows that each unit increase in mother’s self-rated health (representing a decrease in health) is significantly associated with younger age at first birth for daughter in the sample overall (hazard ratio = 1.29, t = 5.28). Thus, we do find support for our first hypothesis.

Model 2 adds three controls for daughter’s race/ethnicity, comparing each group to white young women. As seen in Table 11.2, black adolescents have the highest risk of early first non-marital birth (hazard ratio = 3.45, t = 8.82). Coefficients for Hispanic and other race/ethnicity do not reach statistical significance. The coefficient associated with mother’s self-rated health remains largely unchanged when adjusting for race/ethnicity in Model 2 (hazard ratio = 1.19, t = 3.12) or other maternal characteristics, including whether the mother herself experienced a birth before age 19, in Model 3 (hazard ratio = 1.62, t = 4.40).

To test whether maternal self-rated health status matters similarly in the timing of first non-marital birth across race and ethnic groups, we include the interaction of maternal self-rated health and race/ethnic group. Hypothesis 2 predicted that the association between maternal self-rated health and age at age at first birth would be stronger for black and Hispanic versus white young women, with minority women having a younger average age at first birth what whites. A joint test of significance for all the race/ethnic interactions was significant (chi-square test of joint significance is p < 0.001), indicating that the effects of maternal self-rated health when the adolescent is 14 years old on subsequent early childbearing varies across race and ethnic groups.

Before disaggregating our results by race and ethnic group, we also estimated a model that fully interacted race/ethnicity with all other maternal and adolescent characteristics used in Model 3 (see Table 11.2). The chi-square test of joint significance was p < 0.0001 again suggesting that disaggregation of Model 3 is appropriate. Thus, we estimated parallel hazard models for each of the three largest race and ethnic groups (black non-Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, and Hispanic) to allow for the comparison of the effects of different variables on early childbearing between race and ethnic groups. We drop the other/race ethnic group for this analysis because of the small sample size.

Table 11.3 represents Model 3 stratified by race and ethnicity. Worse maternal self-rated health when adolescent was 14 years old increases the risk of early childbearing for non-Hispanic whites (risk ratio = 1.50, t = 3.36), but not for blacks or Hispanics, controlling for other maternal and household characteristics. Thus, we do not find support for our second hypothesis. Despite earlier evidence that the association between maternal self-rated health status and early fertility behavior among non-Hispanic black young women was stronger than the association among non-Hispanic white and Hispanic young women, once we estimated a fully interactive model the results changed.

Among black young women, having a currently divorced or separated (and not remarried) or single mother when the daughter was age 14, and having a mother who had given birth as a teenager, both increased the likelihood of early childbearing. For all young women, maternal years of education was protective against an early childbearing, although the association did not reach statistical significance at the p = .05 level for Hispanic young women. Among Hispanic adolescents, no other variables in the model reached statistical significance, which may reflect the small sample size.

Robustness Check. Although we do find a significant association between maternal self-rated health and early childbearing among the young women in our sample, especially non-Hispanic whites, it is also possible that these young women are actually using community rather than maternal information as the basis for fertility behavior. We assess how much adolescents consider conditions in their local community relative to the health status of their mothers to determine the likelihood that they will experience poor health as they reach adulthood. To test the community reference hypothesis, we obtain the residuals from a model that predicts mother’s self-rated health using other maternal characteristics. These residuals are a measure of mother’s predicted health status relative to women with similar race/ethnicity, education, income, employment, marital status, and early childbearing status (i.e., birth prior to age 19). We then compare the coefficient belonging to the standardized residual to the coefficients belonging to a standardized version of maternal self-rated health from a bivariate model predicting early childbearing. This comparison provides a test of whether adolescents attend more to their mothers’ health status in an absolute sense (i.e., excellent versus poor) or relative to what is typical for their mothers’ peers. This approach does not provide a direct measure of the health of the neighborhood, but it provides an approximation of what adolescents are seeing in their community.

Results from this analysis showed that the hazard ratio associated with the standardized residuals did not differ significantly from 1.0 (hazard ratio = 0.908, p = 0.089), whereas the hazard ratio associated with observed maternal health status was significantly different from 1.0 (hazard ratio = 0.76, p < 0.0001). Therefore, we conclude that adolescents’ early childbearing is more strongly associated with absolute maternal health status than with maternal health status relative to her mothers’ peers (i.e., the community).

Discussion

Existing research finds that early, non-marital childbearing is more common among race/ethnic minorities, especially African Americans and Hispanics, that whites (Hamilton et al. 2009; Santelli et al. 2009). The weathering hypothesis has been used to explain this difference (Geronimus 1992b, 1996). The thesis states that early pregnancy and childbearing is a rational fertility decision for socioeconomically disadvantaged women especially if they believe they will age rapidly and have a shortened life span. Thus, early child bearing may be a more normative behavior among young women who are surrounded by adults in poor health. In particular, young women may use the health of their own mother as a proxy for rapid aging and shift peak reproductive years to an earlier stage in the life course.

Our results present the first direct test of the weathering hypothesis’ assumption that young women’s fertility decisions incorporate information about the health status of individuals around them. We find evidence that adolescent girls with mothers who have worse self-rated health are more likely to have an early non-marital birth, consistent with the weathering hypothesis as originally proposed. That is, young women consider expectancies about their own health status when making fertility decisions before the age of 19. Contrary to the original thesis, however, we fail to find evidence that these expectancies, as proxied by maternal self-rated health, can account for the race and ethnic differences in the timing of early childbearing. Our results show that a relationship between maternal self-rated health and early childbearing is only evident among non-Hispanic white young women in our study but not among non-Hispanic black or Hispanic young women. In other words, we find support for the weathering hypothesis among non-Hispanic whites, but not among traditionally disadvantaged adolescents.

We can only speculate as to why the weathering hypothesis did not hold for the more disadvantaged young women in our sample. Certainly, black and Hispanic young women had higher rates of non-marital childbearing prior to age 19 than whites in our sample. And when we controlled for race/ethnicity, rather than conditioned on race/ethnicity (i.e., ran separate models for each group), poor maternal self-rated health was associated with significantly higher odds of early childbearing. It may be that other factors, such as family socioeconomic status or the young woman’s academic abilities, may mask the association between maternal health and fertility decisions. That is, minority young women may be more aware of their own economic opportunities (or lack thereof), rather than their future health expectancies. If they believe that their life circumstances are unlikely to improve, there is no reason to delay childbearing. In their qualitative work in disadvantaged communities, Edin and Kefalas (2005) found that early childbearing, typically outside of marriage, provided women with a sense of purpose and gave their lives meaning when faced with limited economic prospects. Further, some combination of economic and health expectancies may doubly-disadvantage some groups relative to others. So although this analysis did not find support for the weathering hypothesis among non-Hispanic black and Hispanic young women, it should not be taken as evidence against the weathering hypothesis. Instead, the results presented here suggest that the weathering hypothesis may need to be more nuanced, especially in terms of exactly what information young women use to make early fertility decisions.

Limitations

The analysis is not without limitations. First, the PSID is an older dataset and in as much as period effects may be at work the applicability of our findings to current rates of, trends in, and reasons for early childbearing may be in question. Second, the data contain a small number of Hispanic young women and an even smaller number of young women of other race/ethnicities. Because rates of teenage pregnancy and early childbearing vary across this dimension, it would be useful to have information from other race/ethnic groups, especially Asian and Pacific Islanders and Native Americans and American Indians. Third, our analysis uses maternal self-rated health as a proxy for future health because other measures of health, like obesity or specific disease outcomes, are not available in the PSID until much later. Despite the fact that self-rated health is strongly correlated with actual physical health, if we had operationalized health in a different way, our results may have shown more variation across race/ethnicity. Similarly, we have no way of knowing whether a young woman consciously used observed maternal health status as a factor in fertility decision making. Few data sets could allow for such an analysis, which suggests that future studies should consider including queries about reasons that young women give for early pregnancy and childbirth and what their own health expectancies are.

Future research may want to explore why expectancies, as measured by maternal health status, appear to matter for non-Hispanic white, but not other minority young women. It is possible that maternal self-rated health does matter for black and Hispanic women but once other maternal and family characteristics are accounted for the association does not reach statistical significance. It could be that maternal health status is associated with daughters’ early fertility decisions but that maternal health status is itself a proxy for socioeconomic status. Our results seem to support this hypothesis. In the race/ethnic specific models, maternal education was a significant protective factor among all groups. Existing research also shows a clear association between educational attainment and health, such that individuals with more education are also healthier (Elo 2009). Although beyond the scope of this paper, the interrelationships between early childbearing, maternal health, and family socioeconomic status should be the focus of future work.

Conclusion

This analysis represents the first attempt to empirically test one of the implicit assumptions of the weathering hypothesis, namely that young women base their own fertility decisions on the health of adults around them. Although the results do suggest that poor maternal self-rated health is associated with early childbearing among young women in the sample, once other maternal and family characteristics are accounted for, this association is only significant for non-Hispanic whites. These findings should not be used to discredit the weathering hypothesis. Rather, they highlight how complicated the causes of early childbearing are.

Notes

- 1.

Throughout the paper we use the terms African American and black and Latino and Hispanic interchangeably.

- 2.

Of the 380 births we observe in the analytic sample only 16 occurred after the daughter was married. In 14 of those 16 cases the birth occurred by the daughter’s next birthday which suggests that the young woman may have known of her pregnancy at the time she married (i.e., these may have been “shotgun” weddings). The remaining two cases involved a birth two years after the year of the wedding. Because we only have the year of birth and the year of the marriage we cannot definitively identify whether the young woman would have been aware of her pregnancy at the time of the wedding. An additional 24 cases experience birth and marriage in the same year. All 40 of these cases were considered censored at the time of first marriage.

References

Ananth, C. V., Misra, D. P., Demissie, K., & Smulian, J. C. (2001). Rates of preterm delivery among black women and white women in the United States over two decades: An age-period-cohort analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154(7), 657–665.

Azjen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Azjen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44, 1175–1184.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bennett, N. G., Bloom, D. E., & Miller, C. K. (1995). The influence of nonmarital childbearing on the formation of first marriages. Demography, 32(1), 47–62.

Boardman, J. D. (2004). Health pessimism among black and white adults: The role of interpersonal and institutional maltreatment. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 2523–2533.

Borrell, L. N., & Crawford, N. D. (2006). Race, ethnicity, and self-rated health status in the behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28, 387–403.

Brückner, H., Martin, A., & Bearman, P. (2004). Ambivalence and pregnancy: Adolescents’ attitudes, contraceptive use and pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36(6), 248–257.

Buhi, E. R., & Goodson, P. (2007). Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory-guided systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 4–21.

Burton, L. M. (1990). Teenage childbearing as an alternative life-course strategy in multigenerational black families. Human Nature, 1(2), 123–143.

Chevalier, A., & Viitanen, T. K. (2003). The long-run labour market consequences of teenage motherhood in Britain. Journal of Population Economics, 16(2), 1431–1475.

Clark, D. O., & Maddox, G. L. (1992). Racial and social correlates of age-related changes in functioning. Journal of Gerontology, 47, S222–S232.

Clinton, W. J. (1995, January 24). State of the union address. Washington, DC: Joint Session of Congress.

Davies, S. L., DiClemente, R. J., Wingwood, G. M., Person, S. D., Dix, E. S., Harrington, K., Crosby, R. A., & Oh, K. (2006). Predictors of inconsistent contraceptive use among adolescent girls: Findings from a prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(1), 43–49.

Dressler, W. W., Osths, K. S., & Gravlee, C. C. (2005). Race and ethnicity in public health research: Models to explain health disparities. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 231–252.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Elo, I. T. (2009). Social class differentials in health and mortality: Patterns and explanations in a comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 553–572.

Ferraro, K. F. (1993). Are black older adults health-pessimistic? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34, 201–214.

Fletcher, J. M., & Wolfe, B. L. (2009). Education and labor market consequences of teenage childbearing: Evidence using the timing of pregnancy: Outcomes and community fixed effects. Journal of Human Resources, 44(2), 303–325.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1991). As the pendulum swings: Teenage childbearing and social concern. Family Relations, 40(2), 127–138.

Geronimus, A. T. (1991). Teenage childbearing and social reproductive disadvantage: The evolution of complex questions and the demise of simple answers. Family Relations, 40, 463–471.

Geronimus, A. T. (1992a). Teenage childbearing and social disadvantage: Unprotected discourse. Family Relations, 41, 244–248.

Geronimus, A. T. (1992b). The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & Disease, 2, 207–221.

Geronimus, A. T. (1996). Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birth weight: A population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Social Science & Medicine, 42, 589–597.

Geronimus, A. T. (2001). Understanding and eliminating racial inequalities in women’s health in the United States: The role of the weathering conceptual framework. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association, 56(4), 133–136, 149–150.

Geronimus, A. T. (2003). Damned if you do: Culture, identity, privilege, and teenage childbearing in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 57(5), 881–893.

Geronimus, A. T., & Bound, J. (1990). Black/white differences in women’s reproductive-related health status: Evidence from vital statistics. Demography, 27, 457–466.

Geronimus, A. T., & Hillemeier, M. M. (1992). Patterns of blood lead levels in US black and white women. Ethnicity & Disease, 2(3), 222–231.

Geronimus, A. T., & Thompson, J. P. (2004). To denigrate, ignore, or disrupt: The health impact of policy-induced breakdown of urban African American communities of support. Du Bois Review, 1(2), 247–279.

Geronimus, A. T., Andersen, H. F., & Bound, J. (1991a). Differences in hypertension prevalence among U.S. black and white women of childbearing age. Public Health Reports, 106, 393–399.

Geronimus, A. T., Neidert, L. J., & Bound, J. (1991b). Age patterns of smoking among U.S. black and white women (Research Report 91-232). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Population Studies Center.

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., Waidmann, T. A., Hillemeier, M. M., & Burns, P. B. (1996). Excess mortality among blacks and whites in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 335(21), 1552–1558.

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., & Waidmann, T. A. (1999). Health inequality and population variation in fertility-timing. Social Science & Medicine, 49, 1623–1636.

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., Waidmann, T. A., Colen, C. G., & Steffick, D. (2001). Inequality in life expectancy, functional status, and active life expectancy across selected black and white populations in the United States. Demography, 38, 227–251.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age-patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 826–833.

Geronimus, A. T., Keene, D., Hicken, M., & Bound, J. (2007). Black-white differences in age trajectories of hypertension prevalence among adult women and men, 1999–2002. Ethnicity & Disease, 17(1), 40–48.

Gilbert, W. M., Young, A. L., & Danielsen, B. (2007). Pregnancy outcomes in women with chronic hypertension. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 52(11), 1046–1051.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2009). Births: Preliminary data for 2007. National Center for Health Statistics. Available via http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_12.pdf. Cited 28 July 2009.

Harper, S., Lynch, J., Burris, S., & Smith, G. D. (2007). Trends in black-white life expectancy gap in the United States, 1983–2003. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(11), 1224–1232.

Hayes, C. (Ed.). (1987). Risking the future (Vol. 1). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Heyman, K. M., Barnes, P. M., & Schiller, J. S. (2009). Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Available via http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/released200906.htm#11. Cited 27 July 2009.

Hoffman, S. D., Foster, E. M., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1993). Reevaluating the costs of teenage childbearing. Demography, 30(1), 1–13.

Hotz, V. J., McElroy, S. W., & Sanders, S. G. (1997). The impacts of teenage childbearing on the mothers and the consequences of those impacts for government. In R. A. Maynard (Ed.), Kids having kids: Economic and social consequences of teen pregnancy (pp. 55–94). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press.

Jaccard, J., Dodge, T., & Dittus, P. (2003). Do adolescents want to avoid pregnancy? Attitudes towards pregnancy as predictors of pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(2), 79–83.

Kelley-Moore, J. A., & Ferraro, K. F. (2004). The black/white disability gap: Persistent inequality in later life? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 59B(1), S34–S43.

Klein, J. D., & the Committee on Adolescence. (2005). Current trends and issues. Pediatrics, 116(1), 281–286.

Klepinger, D., Lundberg, S., & Plotnick, R. (1999). How does adolescent fertility affect the human capital and wages of young women. Journal of Human Resources, 34(3), 421–448.

Lancaster, J. B., Geronimus, A. T., Hamburg, B. A., & Kramer, K. (2008). Introduction to the transaction edition. In J. B. Lancaster & B. A. Hamburg (Eds.), School-age pregnancy and parenthood (pp. ix–xxx). Edison: AldineTransaction.

Lawlor, D. A., & Shaw, M. (2002). Too much too young? Teenage pregnancy is not a public health problem. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(3), 552–553.

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. The New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 171–179.

McEwen, B. S. (2000). Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology, 22(2), 108–124.

Miller, N. E., & Dollard, J. (1941). Social learning and imitation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mollborn, S. (2009). Norms about nonmarital pregnancy and willingness to provide resources to unwed parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 122–134.

Myklestad, I., & Rise, J. (2007). Predicting willingness to engage in unsafe sex and intention to perform sexual protective behaviors among adolescents. Journal of Health Education and Behavior, 34, 686–699.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2009). Health, United States, 2008. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics.

Olson, L. (1980). Social and psychological correlates of pregnancy resolution among adolescent women: A review. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 50, 432–445.

Rich-Edwards, J. W. (2002). Teen pregnancy is not a public health crisis in the United States. It is time we made it one. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(3), 555–556.

Rich-Edwards, J. W., Buka, S. L., Brennan, R. T., & Earls, F. (2003). Diverging associations of maternal age with low birthweight for black and white mothers. International Journal of Epidemiology, 3, 83–90.

Rosenberg, T. J., Garbers, S., Lipkind, H., & Chiasson, M. A. (2005). Maternal obesity and diabetes as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes: Differences among 4 racial/ethnic groups. American Journal of Public Health, 95(9), 1545–1551.

Rosengard, C., Phipps, M. G., Adler, N. E., & Ellen, J. M. (2004). Adolescent pregnancy intentions and pregnancy outcomes: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 453–461.

Rosengard, C., Pollock, L., Weitzen, S., Meers, A., & Phipps, M. G. (2006). Concepts of the advantages and disadvantages of teenage childbearing among pregnant adolescents: A qualitative analysis. Pediatrics, 118, 503–510.

Royston, P. (2005). Multiple imputation of missing values: Update of ice. The Stata Journal, 5, 527–536.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Santelli, J. S., Orr, M., Lindberg, L. D., & Diaz, D. C. (2009). Changing behavioral risk for pregnancy among high school students in the United States, 1991–2007. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 25–32.

Satcher, D., Fryer, G. E., Jr., McCann, J., Troutman, A., Woolf, S. H., & Rust, G. (2005). What if we were equal? A comparison of the black-white mortality gap in 1960 and 2000. Health Affairs, 24(2), 459–464.

Scally, G. (2002). Too much too young? Teenage pregnancy is a public health, not a clinical, problem. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(3), 554–555.

Shuey, K. M., & Willson, A. E. (2008). Cumulative disadvantage and black-white disparities in life-course health trajectories. Research on Aging, 30, 200–225.

Spencer, S. M., Schulz, R., Rooks, R. N., Albert, S. M., Thorpe, R. J., Jr., Brenes, G. A., Harris, T. B., Koster, A., Satterfield, S., Ayonayon, H. N., & Newman, A. B. (2009). Racial differences in self-rated health at similar levels of physical functioning: An examination of health pessimism in the health, aging, and body composition study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 64B(1), 87–94.

Stack, C., & Burton, L. M. (1993). Kinscripts. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 24, 157–170.

Wildsmith, E. M. (2002). Testing the weathering hypothesis among Mexican-origin women. Ethnicity & Disease, 12, 470–479.

Williams, D. R. (1999). Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 173–188.

Williams, D. R., & Jackson, P. B. (2005). Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Affairs, 24(2), 325–334.

Wong, M. D., Shapiro, M. F., Boscardin, W. J., & Ettner, S. L. (2002). Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347, 1585–1592.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a seed grant from the RAND Population Research Center (Meadows and Beckett, PIs). Support was also provided by Panel Study of Income Dynamics (Beckett, and Meadows, PIs).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix A: Descriptive Statistics for the Imputed Sample

Appendix A: Descriptive Statistics for the Imputed Sample

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Meadows, S.O., Beckett, M.K., Elliott, M.N., Petersen, C. (2013). Maternal Health Status and Early Childbearing: A Test of the Weathering Hypothesis. In: Hoque, N., McGehee, M., Bradshaw, B. (eds) Applied Demography and Public Health. Applied Demography Series, vol 3. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6140-7_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6140-7_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-6139-1

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-6140-7

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)