Abstract

Although Adam Smith’s recognition of humans’ propensity to ‘truck, barter, and exchange’ was made in the context of private markets, this same propensity also applies to political markets. With the increasing recognition of, and appreciation for, the fact that forests generate multiple values, some of which are public goods, comes a strong implication that our understanding of sustainable forest management generally and forest economics specifically will be enhanced by explicitly incorporating principles of decision-making in a collective market context—public choice analysis. The self-interested behavior of politicians (elected), bureaucrats (unelected), and voluntary associations of individuals (NGOs) combined with the agency problems inherent to representative government has strong implications for the decision-making environment of private timberland owners. Unlike individuals who plant traditional row crops that are harvested after one growing season, timber growers make decisions that span (perhaps several) dozens of years. As public-ness aspects of forests increase in value, collective decisions increasingly will influence forest management generally and private decision-making by landowners. But long-term decisions made even under conditions of scientific certainty necessarily are made in a context of political uncertainty. This political uncertainty must be integrated into models of sustainable forest management.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Agency problem

- Collective markets

- Multiple forest values

- Policy outcomes

- Private markets

- Political markets

- Public choice

- Rent seeking

- Sustainable forest management

- Voting

1 Introduction

Although Adam Smith’s recognition of humans’ propensity to ‘truck, barter, and exchange’ was made in the context of private markets, this same propensity also applies to political markets. With the increasing recognition of, and appreciation for, the fact that forests generate multiple values, some of which are public goods, comes a strong implication that our understanding of sustainable forest management generally and forest economics specifically will be enhanced by explicitly incorporating principles of decision-making in a collective market context. The self-interested behavior of politicians (elected), bureaucrats (unelected), and voluntary associations of individuals (NGOs) combined with the agency problems inherent to representative government has strong implications for the decision-making environment of private timberland owners. Unlike individuals who plant traditional row crops that are harvested after one growing season, timber growers make decisions that span (perhaps several) dozens of years. As public-ness aspects of forests increase in value, collective decisions increasingly will influence forest management generally and private decision-making by landowners. But long-term decisions made even under conditions of scientific certainty necessarily are made in a context of political uncertainty. This political uncertainty must be integrated into models of sustainable forest management.

In the latter part of the twentieth century, what has aptly been referred to as the ‘Public Choice revolution’ swept through the academic disciplines of economics and political science. Briefly, the central tenet of Public Choice is that the individuals in whom public trust is placedFootnote 1 are motivated not by the desire to improve social welfare but, rather, by the desire to improve their own personal well-being. This simple observation has dramatic implications for the design, functioning, and performance of political and social institutions narrowly and country-level economic performance more broadly; a large body of scientific literature that focuses on these implications has developed in recent years.

For example, there is evidence suggesting that macroeconomic indicators such as inflation and unemployment move systematically with election cycles. The notion that incumbent politicians exert (at least some, perhaps indirect) control over macroeconomic conditions in order to boost their (re)election probabilities is referred to as the political business cycle (Drazen 2008). The efforts by individuals and interest groups to use government as a means of re-distributing wealth in their favor are socially damaging, as they reduce economic growth (Olson 1965; Laband and Sophocleus 1992; Rauch 1994). Elected representatives cartelize public sector production, restricting competition and raising the ‘price’ (in the form of campaign contributions) of their services (McCormick and Tollison 1978). Indeed, there is evidence that politicians in the U.S., at least, deliberately introduce legislation targeting specific industries for onerous regulations as a means of inducing firms in the potentially affected industries to ‘voluntarily’ contribute money to incumbent politicians who are in a position to make sure the legislation dies in committee, after the obligatory public bashing of industry representatives in front of a congressional ‘investigative’ committee (McChesney 1987, 1997).

With respect to the interface between politics and forestry/natural resources, recent contributions include the demonstration by Laband (2001) that voting in the political commons generates over-supply of environmental regulations targeting private landowners, analyses showing that special interest group politics influenced both congressional voting on the Endangered Species Act amendments in the United States (Mehmood and Zhang 2001) and congressional support for restrictions on imports of Canadian softwood lumber (Zhang and Laband 2005), a study by Tanger et al. (2011) showing that congressional support for environmental legislation in the U.S. over the period 1970–2008 was influenced by macroeconomic conditions, and superb contributions by Lueck and Michael (2003) and Zhang (2004) demonstrating that private landowners in close proximity to Red-cockaded woodpeckers (RCW), listed under the Endangered Species Act, pre-emptively harvest timber to preclude development of suitable habitat for RCW.

It should be understood, of course, that the economic performance of countries is nothing more than an aggregate of the economic performance of a large number of individual sectors of the economies of those countries. Thus, the observation that public choice theory has implications for our understanding of macro-economic performance generally suggests that a more refined focus of our scientific lens to an application of public choice theory to particular sectors and sub-sectors of the economy, such as the forest sector, not only may be desirable but, indeed, essential to our understanding of the structure, functioning, and performance of those (sub)sectors. With this in mind, my objective is to introduce and apply several highly-relevant and important aspects of public choice theory to forest economics, forest policy and sustainable forest management: Specifically, I focus on three aspects: (1) the relationship between voting and policy outcomes; (2) rent-seeking behavior, and (3) public versus private interests in science and policy. For the most part, my discussion is couched in terms of forestry practices and policies in the United States, but similar policies and practices are evident all around the world.

2 The Relationship Between Voting and Policy Outcomes

Forestry is shaped predominantly by markets, for inputs (e.g., land, labor, seedlings, herbicides and fertilizers) as well as the demand for final products. These markets are characterized by prices that reflect the values that both buyers and sellers place on the inputs and outputs. In turn, the information conveyed by these prices guides the investment decisions made by hundreds of thousands of individuals—landowners, land managers, seedling growers, home builders, and so on. In this context, the ‘invisible hand’ of private markets harnesses the self-interest of individuals in such a way that the social well-being of consumers is promoted (Smith 1776).

But these markets are impacted significantly by politically-determined conditions. Timber supply is affected by a host of political decisions, such as the amount of timber harvesting permitted on publicly-owned lands and regulations that determine the availability and cost of inputs, such as herbicides. Statutory restrictions on harvesting and other timber-related activities, re-planting requirements, and taxes levied on the profits that accrue from harvesting wood on privately-owned land all are determined by legislation. Likewise, political decisions also influence the demand for timber, wood products, and fiber products, such as cellulosic bio-fuels and paperboard. However, these political decisions do not necessarily, or even often, serve/promote the public interest. Failure to do so need not imply anything insidious about the motives or behavior of politicians. Rather, it may reflect one of the defining (and therefore crucial) differences between private markets and public markets with respect to decision-making: the efficacy with which preferences and values are expressed.

In private markets, preferences and values are expressed clearly and with great precision in terms of the prices that individuals are willing to pay/accept for goods and services. The individual who values a piece of fruit more than the selling price purchases and consumes it; importantly, no individual who values that fruit less-than the selling price is compelled to purchase and consume it. Decisions made in this context necessarily promote both individual and social welfare because exchange is voluntary; no one participates unless their welfare is enhanced by the transaction.

In public markets, individual preferences and values are expressed not in terms of money but in terms of votes and production and consumption decisions are determined by a process that aggregates these votes. Frequently, the candidate/issue/proposal that gains a simple majority of the votes cast ‘wins’, but the simple majority outcome need not to be economically efficient. A brief example will serve to demonstrate the potential inefficiency of a simple majority decision rule.

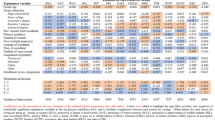

Each individual in a 3-member society is asked to vote express a preference between 2 forest conservation projects—(CP-1), which focuses on protection of endangered species to the exclusion of humans, and (CP-2), devoted to recreational uses for humans. In Table 7.1, the values attached to each project by each individual are identified. All three individuals place a positive value on each of the projects. Individuals A and B each value CP-2 twice as highly as CP-1 and vote accordingly. However, individual C not only values CP-1 much more highly than CP-2, the value he places on CP-1 is many times the collective value placed on CP-2 by all other members of society. Yet because the mechanism for revealing social preferences for public works projects elicits only a preference between the two projects, not the intensity of desire for each project, a simple majority decision rule generates a less-than-optimal public sector production decision. The sub-optimality easily can be seen by contemplating a side payment from C to B in the amount of $3 and from C to A in the amount of $21, conditional on them both voting in support of CP-1. If this deal is made, total social welfare increases from $50–$4022 and all parties are better off.Footnote 2 But, political side payments of this sort typically are discouraged. Of course, in a majority-rule context, C need only arrange a side payment of $3 to B to generate a vote in favor of CP-1.

It need not be the case that all members of society benefit from both projects. As indicated in Table 7.2, one or more individuals (in this case C) actually may be injured by one or both of the projects being voted on. As before, both A and B vote in support of the park, and C is adamantly opposed to the park because it will impose substantial harm on him. Simple majority rule implies that CP-2 will be enacted, even though the total social value of CP-2 is negative. Again, relatively low side payments from C to A and C to B not only would make all three members of society better off, they would generate a positive social outcome rather than a negative social outcome.

Only in the extreme case of decisions reached by unanimous consent, we are guaranteed that all individuals, and therefore society as a whole, are better off (Buchanan and Tullock 1962). The potential inefficiencies introduced by less-than-unanimity voting rules coupled with how poorly votes reflect intensity of preferences may be magnified considerably by representative government. Although the United States and a number of other countries routinely are referred to as ‘Democracies,’ in fact they are Representative Republics, in which a relatively small number of elected representatives actually vote directly on policy initiatives. With a simple majority decision rule, a relatively small minority of voters potentially can determine policy outcomes.

Consider a society that consists of 121 individuals, divided equally into 11 political jurisdictions, each of which is served by a representative who is elected by simple majority. Representatives are chosen from one of two parties: the ‘Donkeys’ and the ‘Elephants’. The distribution of the votes, in total and by district, is revealed in Table 7.3.

In this stylized world, the popular vote favors the Donkeys 85–36, a better than 2–1 margin. Yet the representative assembly is controlled by the Elephants, 6–5. Going further, it should be clear that each of the 5 individuals who vote for the Donkey candidate in districts 1–6 might have very intense feelings about that candidate, whereas each of the 6 individuals who vote for the Elephant candidate may have only a slight preference in this regard over the Donkey candidate. That is, in terms of reflecting values that are an essential basis for individual and social welfare-enhancing collective decision-making, representative government may dramatically exacerbate the likelihood that public policy: (a) is driven by a relatively small percentage of the voters, and (b) improves the well-being of select individuals while harming others.

3 Rent-Seeking Behavior

Through spending programs and regulations, governments redistribute wealth from certain individuals in society to others. This wealth transfer aspect of government can be extremely damaging to society. While we may agree that certain wealth transfers are desirable and promote the social good, the more general problem is that virtually every member of society prefers to receive wealth transfers rather than be forced (through taxation or regulation) to give his/her wealth to others. This aspect of self-interest leads inevitably to efforts by individuals to use the apparatus of government to arrange wealth transfers in their favor. In turn, such efforts motivate reciprocal efforts by other individuals seeking to prevent their wealth from being appropriated by the State. These expenditures by individuals to influence state-arranged wealth transfers are known as ‘rent-seeking’ (Tullock 1967; Stigler 1971; Krueger 1974; Posner 1974; Peltzman 1976). The scope and extent of rent-seeking activities has been found to be quite sizable, even in the western democracies (Laband and Sophocleus 1992) and fundamentally distorts our understanding of Gross Domestic Product (Mixon et al. 1994).Footnote 3 The fact that resources that could be used to enhance real productivity instead are used to influence the distribution of wealth implies that the economic well-being of countries is tied directly to the level of rent-seeking activity (Olson 1965; Rauch 1994). This is why graft and corruption inhibit economic growth, but then so do political campaign contributions.

The process of rent-seeking is well-understood. Successful rent-seekers will structure wealth transfers in such a manner that: (a) a relatively large number of people pay (the aggregate amount to be gained by the rent-seeking group is large), (b) each targeted individual pays only a small amount (so there is relatively little individual incentive to protest the wealth transfer), (c) the wealth is transferred to a relatively small number of recipients, such as industrial timberland owners, and (d) the motive for the wealth transfer is not transparent. That is, it does not pay to tell other people your actions are motivated merely by the desire to take their wealth from them. They will not feel good about this and fight to prevent the transfer from taking place. Therefore, wealth transfers invariably are disguised beneath a cloak of public-interest rhetoric, such as ‘to help the children’ or ‘to save the environment’. People seem to feel better about handing over their money when it is for a noble cause. Wars against what are claimed to be particularly vicious enemies are an especially good cover for interest groups seeking wealth transfers. This explains why, for example, those who are skeptical about anthropogenic global warming are painted in such a negative light.

Arguably, almost everything related to the public policy process is driven, to some degree, by this wealth redistribution imperative. A not-so-subtle implication of this focus is that judging policy outcomes on the basis of social welfare maximization criteria is likely to prove frustrating, if not embarrassing. For example, I have argued for many years that not only could I actually win America’s so-called “War on Drugs”, I could do so quite cheaply and quickly. All that would be required is for the U.S. Government to lace several captured drug shipments with cyanide and put them back onto the streets. That is, mercilessly and definitively drive home the message that drugs kill. This simple and low-cost action would turn drug use from an activity with an expected positive return to users to an activity with an expected large negative return to users. I rather imagine that demand for cocaine and other illegal drugs in the U.S. would decline quickly and dramatically.

If we can agree that this strategy would, indeed, have the claimed effect—an immediate and very strong decline in demand by users—then we would agree that, in fact, America’s War on Drugs can be won. This is a ‘war’ that we have been fighting for many decades now, that we have spent literally hundreds of billions of dollars on, that has cost many thousands of completely innocent individuals their lives, with extensive collateral damage outside of the U.S., and that by many accounts is a complete and utter failure in terms of reduced drug use/demand/availability. So why keep on pursuing the same policy failure for decades?

The answer is that the policy objective is not to actually win this war—the objective is to redistribute a lot of money. The War on Drugs is a multi-faceted means of funneling money (indirectly in the form of jobs) to many tens of thousands of judges, law enforcement personnel, social services workers, etc. The financial welfare of a large number of individuals depends specifically on continuation of the high-cost ineffective policy. That is, judged from a wealth redistribution perspective, America’s War on Drugs has been a tremendous success rather than an abysmal failure.Footnote 4

Note that it would actually be socially beneficial to win the War on Drugs and simply give the no-longer-needed judges, policemen and social services workers continuing payments for not working. But, of course, if voters really understood that the wealth transfer was the true objective, they never would agree to such a policy in the first place.

Members of the forestry community are, of course, no less immune from the seductive siren of rent-seeking than other groups. In casual conversation, private timberland owners in the United States are among the most conservative, anti-government individuals you will find. Yet many of these same individuals have lobbied state legislatures (directly or indirectly) to receive favorable tax treatment in several dimensions. For example, they favor protective government tariffs that reduce the competitiveness of softwood lumber grown in Canada (Zhang 2007). Several years ago my colleague, Daowei Zhang, and I created a bit of a furor in the forestry community of the southeastern U.S. when we rather bluntly pointed out this inconsistency (Laband and Zhang 2001).

Rent-seeking poses special problems for the forestry community generally and for timberland owners in particular. For example, in a number of countries, government officials control access to highly valuable timber resources on public lands. Timber is a resource that takes many years to mature. Consequently, timber management that is economically and ecologically sustainable implies a decision-making time-frame that is incompatible with the time frame of most government officials. They can personally appropriate the value from public assets only if the timber resource is exploited while they are in office. So they are particularly susceptible to rent-seeking efforts by companies that are willing to get in and harvest timber immediately.

This is why ‘illegal’ logging is such a difficult problem to deal with. When faced with charges of illegal logging taking place in their country, self-interested government officials either deny that a problem exists or refuse to take action because they likely have a financial stake in that illegal logging. To say that they are wrong is to deny the importance of human nature. The problem is not political corruption per se, it is the fact that the incentives of the stewards of the land are not compatible with the incentives of the (current and future) owners of the land. This incentive incompatibility problem implies that timber and other exploitable, publicly-owned resources will continue to be over-exploited unless they are given exceptionally strong legal protections.

In recent decades, human populations have become increasingly urbanized everywhere around the world. Not surprisingly, urban dwellers are not connected to the land the way rural dwellers are; their values and perspectives differ significantly. However, in countries with democratic governments urban dwellers share one important characteristic in common with rural dwellers: their votes count equally. As populations become more urbanized, then, urban dwellers increasingly are able to define and control policy outcomes that affect rural life. This might, perhaps usefully, be referred to as the political urban-rural interface and manifests itself in a variety of different dimensions. I’ll focus on one aspect in particular: what I have referred to previously as the “Tragedy of the Political Commons” (Laband 2001; Hussain and Laband 2005).

As I noted in that 2001 paper (p. 22), “A serious threat to private landowners develops when citizens living in urban areas demand that private owners of timberland (definitionally located in rural areas) produce environmental amenities such as aesthetically pleasing views, biodiversity, animal habitat, and the like, provided the urbanites don’t have to pay for it”. This threat is actualized when urban dwellers: “…enforce their demands by using the political process to pass regulations that require landowners disproportionately to bear the cost of producing these environmental amenities”.

Examples of such public policies abound. In certain locations around the world, private property owners are required to permit others access to their land in order to pick berries or mushrooms. That is, the non-owners have certain statutory rights of consumption. In the state of Oregon, private timberland owners are required by state law to replant within two years areas from which they cut trees. Other regulations specify permissible harvesting regimes (for example, the size and spatial patterning of clear-cutting timber, even on flat ground). In the United States, federal regulations pertaining to endangered species are incredibly restrictive and intrusive with respect to an individual’s property rights.

These public policies are striking in one key respect: in effect they redistribute wealth from rural land owners to people who live in cities. That is, urban dwellers in the U.S. have the political power to control voting outcomes and pursue environmental amenities through policies that impose virtually all of the associated costs on relatively small numbers of private landowners. This generates what might be termed a “tragedy of the political commons”.

Hardin (1968, p. 1244) introduced us to the tragedy of the commons. Hardin developed a stylized example of a communal pasture open to all comers. There are no private property rights to the pasture, or rules, customs, or norms for shared use. In this setting, each shepherd, seeking to maximize the value of his holdings, keeps adding sheep to his flock as long as doing so adds an increment of gain. Further, the shepherds graze their sheep on the commons as long as the pasture provides any sustenance. Ignorant of the effects of their individual actions on the others, the shepherds collectively (and innocently) destroy the pasture. As Hardin concludes (p. 1244): “Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in freedom of the commons”.

Man’s exploitation of the political commons is analogous to his exploitation of natural-resource commons. Our majority-rule voting process, which permits a majority of citizens to impose differential costs on the minority, encourages overprotection of endangered species, and overproduction of biodiversity, animal habitat, and landscape views. It is precisely the wealth transfer aspect of the simple majority decision rule that generates an over-production of damaging policy.

Legal rule-making can be crafted in a manner that concentrates the costs of policy (there always are costs) on relatively small groups of citizens. This implies that, aside from this small group, other members of the society bear no (or essentially trivial) costs associated with the policy. In turn, this artificially skews individuals’ benefit-cost calculus in favor of over-production of environmental amenities because each individual who bears a negligible portion of the costs of providing environmental amenities has a private incentive to keep demanding additional environmental protections as long as there is any perceived marginal benefit. As with the overgrazed pasture in Garrett Hardin’s famous example, the result of overprotecting Bambi is, as has become apparent all over the eastern United States, both ecologically and economically disastrous. That is, we are creating social and ecological tragedies that result from the political commons.

The tragedy is compounded by the incentives generated for private landowners by these implicit wealth transfers engineered through democratic voting processes. When government intrudes on or appropriates the property rights of private landowners without compensation, the landowners have strong incentives to mitigate their expected losses. They can do so by changing their land use from timber production to housing or commercial development. There is little externally-produced (positive) incentive for landowners to promote habitat for endangered species; rather, doing so means only that use of one’s land will be seriously compromised by the highly restrictive provisions of America’s Endangered Species Act. Consequently, a landowner who finds a member of an endangered species on his property has a well-understood incentive to “shoot, shovel, and shut up”—our colloquial term for making sure that no members of an endangered species are found on his property. Such behaviors are not likely to help society achieve even widely-shared environmental objectives.

3.1 Linking Wealth Transfers to Excessive Environmental Regulations

It is worth pursuing further the argument made previously that because private owners of rural land bear the cost of producing biodiversity (and other environmental amenities), urban dwellers demand excessive amounts of it. The first point to be made in this regard is that urbanites do not in fact place a high value on biodiversity. One needs look no further than the readily observable behavior of urbanites for proof of this claim. Urbanites have the ability and prerogative to produce biodiversity on their own residential property. That is, they could let their residential lots grow wild with natural flora and fauna. This would, without question, promote ecological diversity. In practice, virtually no residential property owners, living anywhere in the United States or other industrialized countries, do this. Instead, they invest (implicitly through their time and explicitly by purchase) hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars annually in the care and maintenance of their lawns and grounds in a decidedly unnatural state. Like owners of intensively managed timberland, owners of residential property chemically treat and harvest the growth on their property. In so doing, they create a landscape with relatively little floral or faunal diversity. What this behavior reveals, of course, is that urban dwellers place a higher value on having their own aesthetically pleasing ecological deserts than on personally promoting local biodiversity, even when the latter would save them hundreds, perhaps thousands, of dollars each year. The clear implication is that urbanites simply do not attach much importance to biodiversity.

This leads directly to a second point: notwithstanding the observation that biodiversity is of little importance to them personally, urbanites may favor local, state, and federal statutes that ostensibly enhance biodiversity, provided such statutes impose the cost burden on others (e.g., rural landowners). The marginal, feel good benefit of such regulations may be miniscule, but with no personal costs to worry about, urbanites can be convinced to vote for them. However, if there were even a moderate cost to urban dwellers, we can be reasonably certain that restrictive regulations would not be passed. This explains why, for example, timber replanting regulations typically are not imposed on owners of residential properties who cut down trees.

As the divergence in values, perspectives, and knowledge about natural systems widens between urban and rural dwellers, the Tragedy of the Political Commons intensifies, as urban dwellers increasingly use their collective political might to transfer wealth from rural land owners, principally through land use restrictions and regulations. This clearly is a long-run issue in sustainable forest management.

3.2 Politically-Derived Risk and the Forestry Community

In contrast to traditional agricultural commodities which mature fully within the context of a single year (or growing season), timber is a crop that takes many years to mature. Consequently, it is very risky for timberland owners to assume that today’s political environment (with policies that artificially influence markets) will remain in place over the length of time covering an entire rotation. The political forces that converged to deliver today’s special price support, tax incentive, or artificially-inflated prices (e.g., pulpwood for biofuel; carbon credits) may not, indeed likely will not, be in place 30, 50, 80 years from now. Thus, the governmentally-influenced component of timber prices, land prices, and other prices associated with the forest sector is subject to a type of volatility and risk that is quite different from the volatility and risk that characterizes truly market-driven prices.

The reason that policies conveying advantage to special interests typically do not endure is because they are not politically sustainable over long periods of time. The fact that government officials create artificially high timber prices this year automatically generates opposition from other interest groups, such as home builders, who will argue that the government policies creating artificially high timber prices should be repealed. Where there is a lot of money at stake, it surely is the case that the affected interest groups will spend a lot of money in efforts to influence the outcome. Under the intense pressure of a major economic downturn, as tax revenues from traditional sources dry up, the special tax treatment of timberland may be open to reconsideration.

In turn, this government-induced volatility tends to generate political fragmentation within the forest sector. For example, individual land owners in the U.S. who currently have a lot of mature timber on their properties likely will favor a government policy that restricts imports of timber from other countries. Such a restriction will drive up the current price of timber in the U.S. generating a short-term profit opportunity for landowners with mature timber. However, such a policy inevitably will harm home builders, who may, on the margin, be driven to embrace non-wood building materials. This will, of course, impose considerable harm on those land owners who hoped to sell their timber for good prices 20 or 30 years from now.

As a second example, we already have seen that markets for carbon credits, which exist specifically and solely because of government policies with respect to carbon, temporarily create financial windfalls for certain timberland owners. Those who acquired carbon credits then sold their timberland when the price of those credits was high to buyers who believed the value of those carbon credits would remain high likely had some portion of the expected stream of future carbon credit payments capitalized into the selling price of their land. These timberland sellers are financial winners. Of course, when it becomes clear that the price of carbon credits will not remain high and the carbon credit-related stream of revenues will not materialize as anticipated, the value of that land will fall back to what is justified in consideration of the realizable and sustainable flow of revenues. Buyers of timberland who paid prices that included the capitalized stream of carbon credit payments will be financial losers when the price of their land falls as the price of the credits falls.

What this means, of course, is that while there may be a perception within the forest community that carbon credits are a no-risk money-maker for timberland owners, the reality is different. No doubt, certain current owners of timberland have benefited and will benefit financially. But those gains may, and likely will prove to, be transitory. As political support for carbon restrictions ebbs, we will be left with a mosaic of timberland owners—some who did not participate in the carbon markets, some who gained financially, others who lost financially.

The problem with lusting after government favors is that what the government does today can be undone and more tomorrow. But, of course, once a group has been the beneficiary of government-arranged wealth transfers, or, indeed, even lobbied unsuccessfully for such transfers, it loses its political innocence. Then it is too late for members of that group to claim, with any legitimacy, that this type of governmentally-arranged theft is objectionable.

4 Public Versus Private Interests in Science/Policy

The pursuit of self-interest in private markets characterized by voluntary transactions between informed participants necessarily improves social welfare. I have argued that in the context of political markets, self-interest can be, and frequently is, used to redistribute existing wealth rather than creating new wealth. From piracy to large-scale tribal or national butchery, mankind’s historical record provides ample evidence of the immense importance of efforts to redistribute wealth.

Individuals kill each other over card games, affairs with spouses, lawsuits, property boundaries, illegal drugs, stealing cattle, on so on. For centuries, Jews consistently have been targets for abuse and murder in order to obtain their wealth. Slavery is, at heart, wealth redistribution, as the slaver appropriates the stream of labor services provided by the slave. If the slaver did not covet the value of these services, the slave would merely be killed. History-defining wars—such as America’s War of Independence against England, America’s War Between the States, and World Wars I and II—were engaged primarily because of wealth redistribution considerations. Surely the historical social toll of efforts to influence the distribution of wealth runs into the hundreds of millions of lives damaged or lost. Many otherwise good men and women succumb to the overpowering desire to appropriate their neighbor’s wealth, in the process committing the most heinous of acts against fellow humans.

Individuals and groups strategically exploit majority-rule democratic processes in efforts to employ the power of government to arrange wealth redistributions from others. In both the public choice literature and, increasingly, the popular press, these self-interest-maximizing individuals are referred to by the rather derisive term, ‘rent-seekers’. Although scientists generally are regarded by the public as dispassionate, arms-length seekers (and tellers) of truth, this implicitly assumes that scientists turn a blind eye to their own self-interest. However, since scientists are no less human than non-scientists, there is no reason to believe that they are any more or less motivated to pursue their own self-interest than other individuals are.

Empirical evidence regarding the self-interest of scientists is easy to come by. My colleague in Auburn University’s School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences, David South, has made offers to bet literally dozens of scientists around the world with respect to the claims they make. Only two (2), including my fellow economist and human population optimist, Julian Simon, have ever been willing to bet their own money on their science. Yet in their pursuit of (mostly publicly-funded) grants, these so-called scientists only too-obviously are willing to prostitute themselves in exchange for a few gold coins. In so doing, they not only destroy their own scientific virtue, they destroy the reputational capital of the scientific community and potentially damage the lives and well-being of literally millions of their fellow human beings. The lure of the wealth transfers is powerful indeed.

In my opinion, it is worth considering whether public policy with respect to anthropogenic global warming is analogous to America’s continuing War on Drugs. A politically-strong collection of interested parties, including climate researchers, develops an enormous financial stake in manufacturing and sustaining a putative danger to the public well-being. This serves as justification to reallocate essentially incomprehensible sums of money from politically unorganized private citizens through taxation and regulation to combat the threat. Individuals engage in rent-seeking, including the continuing insistence of long-term danger, to capture some portion of these funds. To those who might be shocked, perhaps outraged, that I would dare to suggest less-than-noble motivations behind anthropogenic global warming science and policy, I refer you again to my colleague, David South. How many scientists making dire predictions about global warming are willing to bet their own money on the veracity of those claims? How many have relocated their homes from low-lying coastal areas to locations that, in theory, will not be adversely affected by their predicted rise in sea-levels? If they are not willing to do so, what does this imply about the confidence these scientists have in their own work/findings and, as a corollary, the confidence that others should have?

5 Conclusions

History reveals that economic models of the market process explain only part of what happens in the real world. Management decisions with respect to timber as well as ecosystem goods and services produced by nature generally, and forests specifically, are shaped by markets as well as politics. Consequently, real understanding of the forces shaping utilization of forest resources requires knowledge of how both private and public markets operate and interact.

A number of points are suggested by the foregoing discussion. First, depending on circumstances, political markets and commodity markets may be regarded as complements or as substitutes. Development of thriving private markets requires strong protections for private property rights. These protections are collectively defined and enforced. At this fundamental level, the functioning of the State and the functioning of private markets are strongly complementary. Moreover, because private markets do not effectively handle public goods aspects of forests, political decision-making may augment (complement) decisions made by private individuals operating in private markets. However, political markets may be used by self-interested entrepreneurs to separate consumers from their money; in this context rent-seeking is a substitute for profit-seeking activities in private markets. Second, political markets are based on voting, not prices, therefore results of political decision-making, even by direct democracy, are likely to be inefficient because votes do not accurately convey intensity of preference whereas prices do. Third, this inefficiency problem is exacerbated by representative government, because multiple-stage majority-rule decisions may result in a small minority of voters controlling legislative outcomes. In addition, political representatives are ‘bundles’ of numerous public goods/services; for specific elements of this bundle, the representative may not efficiently reflect a voter’s preferences. Fourth, the absence of private-market competition in public markets generates/exacerbates inefficiencies in the supply of public goods/services. Finally, sustainable forestry management requires allocation of both private and public goods; therefore it is necessary to understand the functioning of both types of markets and interactions between them. In particular, it is crucial to understand and appreciate how changing the relative mix between ownership and control of production affects management decisions and outcomes. In the classic agent-principal relationship in private markets, firms are owned by stockholders but managed by individuals whose objectives may differ substantially from those of the stockholders. Recognition of the public aspects of forestry forces us to acknowledge and deal with a related agency problem—forest lands may be owned by private individuals whose objectives, and therefore management decisions, may be controlled, or at least constrained/influenced by millions of voters who have different objectives for the land. This separation of ownership and control has important implications for sustainable forestry management.

Notes

- 1.

This would include unelected bureaucrats and public sector employees in addition to elected politicians.

- 2.

Note that C would be willing to pay up to $3,994 to induce A and/or B to vote for the dam. The improvement in social welfare would be the same but the distribution of the gains to individuals would change.

- 3.

As of this date (14 February 2010) a number of individuals are announced candidates to be the next governor of the state of Alabama—the election will be held in November 2010. It already has been noted by observers commenting in the newspapers that these candidates will spend millions of dollars in the hope of landing a job that pays only $110,000 per year. Of course, the Governor is in a position to steer highly lucrative state contracts to his friends, family, and business associates or to special interests who reciprocate with payoffs to the Governor in the form of campaign contributions (which eventually can be converted to personal use), highly-paid jobs for family members or friends of the governor, etc. The same general tendency pervades politics at all levels in the United States.

- 4.

References

Buchanan JM, Tullock G (1962) The calculus of consent. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Drazen A (2008) Political business cycles. The new palgrave dictionary of economics, 2nd edn

Hardin G (1968) The tragedy of the commons. Science 162:1243–1248

Hussain A, Laband DN (2005) The tragedy of the political commons: evidence from U.S. senate roll call votes on environmental legislation. Public Choice 124(3):353–364

Krueger AO (1974) The political economy of the rent-seeking society. Am Econ Rev 64:291–303

Laband DN (2001) Regulating biodiversity: tragedy in the political commons. Ideas on Liberty 51(9):21–23

Laband DN, Sophocleus JP (1992) An estimate of resource expenditures on transfer activity in the United States. Quart J Econ 107(3):959–983

Laband DN, Zhang D (2001) Tariff a treat for timber industry. Mobile Register Nov 11, 1D

Lueck D, Michael J (2003) Preemptive habitat destruction under the endangered species act. J Law Econ 46(1):27–60

McChesney FS (1987) Rent extraction and rent creation in the economic theory of regulation. J Legal Stud 16(1):101–118

McChesney FS (1997) Money for nothing: politicians, rent extraction, and political extortion. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

McCormick RE, Tollison RD (1978) Legislatures as unions. J Polit Econ 86(1):63–78

Mehmood S, Zhang D (2001) A roll analysis of endangered species act amendment. Am J Agric Econ 83(3):501–512

Mixon F, Laband DN, Ekelund RB Jr (1994) Rent seeking and hidden resource distortion: some empirical evidence. Public Choice 78(2):171–185

Olson M (1965) The rise and decline of nations. Yale University Press, New Haven

Peltzman S (1976) Toward a more general theory of regulation. J Law Econ 19:211–240

Posner RA (1974) Theories of economic regulation. Bell J Econ Manage Sci 5:335–358 Autumn

Rauch J (1994) Demosclerosis. Times Books, New York

Smith A (1776) The wealth of nations. Reprinted 1975, Dutton, New York

Stigler GJ (1971) The economic theory of regulation. Bell J Econ Manage Sci 2:3–21

Tanger SM, Zeng P, Morse WC, Laband DN (2011) Macroeconomic conditions in the U.S. and congressional voting on environmental policy: 1970–2008. Ecol Econ 70(6):1109–1120

Tullock G (1967) The welfare cost of tariffs, monopolies, and theft. West Econ J 5(3):224–232

Yandle B (1983) Bootleggers and baptists: the education of a regulatory economist. Regulation 7(3):12

Yandle B (1998) Bootleggers, baptists, and global warming, PERC policy series, PS-14

Zhang D (2004) Endangered species and timber harvesting: the case of red-cockaded woodpeckers. Econ Inq 42(1):150–165

Zhang D (2007) The softwood lumber war. Resources for the Future (RFF) Press, Washington

Zhang D, Laband DN (2005) From senators to the president: solve the lumber problem or else. Public Choice 123(3–4):393–410

Acknowledgments

Paper was delivered at the Sub-Plenary Session on—New Frontiers of Forest Economics, chaired by Professor Shashi Kant of the University of Toronto, at the XXIII IUFRO World Congress, Seoul, South Korea, August 27, 2010. Helpful comments received from Shashi Kant are gratefully acknowledged. This research was supported by a McIntire-Stennis grant administered through the School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences at Auburn University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Laband, D.N. (2013). Public Choice, Rent-Seeking and the Forest Economics-Policy Nexus. In: Kant, S. (eds) Post-Faustmann Forest Resource Economics. Sustainability, Economics, and Natural Resources, vol 4. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5778-3_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5778-3_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-5777-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-5778-3

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)