Abstract

In this chapter, we start with a description of happiness, the nature of happiness, the value of happiness, and the determinants of happiness. In that context, we discuss what leisure can contribute to happiness. Although happiness is partially “set” through inherited personality traits, there is potential for improving one’s sense of happiness through leisure. Research to date focused mainly on casual leisure and leisure travel. These kinds of leisure have mostly a small positive effect on happiness. The benefits are often temporary and in the moment. We propose more longitudinal research that addresses serious leisure and project-based leisure, which may have more sustained effects on happiness than casual leisure and leisure travel.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Happiness is important to individuals. If one were to make a judgment based on the vast amount of self-help books available in any bookstore, the conclusion would have to be that happiness is a very important aspect of people’s lives. Whether such books actually provide any solutions to increase happiness is doubtful (Bergsma, 2008). Nevertheless, many are clearly interested in happiness.

Contemplations about happiness began hundreds of years ago. Particularly, the ancient Greeks were interested in happiness, among which Aristotle. Aristotle thought of happiness as “living according to reason.” In his view, leading a happy life meant leading a virtuous life (McMahon, 2006).

Since the 1960s, happiness has become a subject of empirical research in the social sciences. The concept of happiness in these empirical studies is different from Aristotle’s view. Rather than leading a morally good life, happiness is regarded as leading a satisfying life. In this chapter, we focus on that latter meaning of the word.

Happiness trainings have also developed since the 1960s. Recently, interventionists and researchers joined forces in the positive psychology movement, which aims to strengthen individuals’ life skills, enabling them to lead happier lives. This is mainly done through positive interventions, some of which are more successful than others (cf., Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). Another strand in this movement focuses not so much on training and soul searching, but gathers objective information on determinants of happiness, with the purpose of enabling people to make better informed choices, that is, minimize discrepancies between expected and experienced utility (Kahneman, Wakker, & Sarin, 1997). This chapter fits the latter strand.

Striving for happiness is not futile; apart from feeling good, being happy has several other advantages as well. One benefit is that happiness lengthens life (Danner, Snowdon, & Friesen, 2001), because happiness protects against becoming ill (Veenhoven, 2008). Longitudinal studies also found that happiness fosters intimate relationships and adds to productivity at work in various ways (Lyubomirsky & King, 2005).

In this chapter, we discuss the relation between happiness and leisure. First, the concepts of leisure and happiness are defined. Next, we explain how leisure can affect happiness and whether it has a positive influence on happiness. We end this chapter with an agenda for future research.

Leisure

We identify leisure as free time which is defined as “time away from unpleasant obligation” (Stebbins, 2001, p. 4). Stebbins distinguishes three types of leisure: serious leisure, casual leisure, and project-based leisure. Serious leisure constitutes three kinds: career volunteering, hobbyist activities, or amateur pursuits. Casual leisure is less substantial and offers no “leisure career.” Project-based leisure is free time dedicated to a leisure project. This type of leisure is short in nature, unlike a hobby. The research presented in this chapter addresses mostly the domain of casual leisure, which is “immediately, intrinsically rewarding, relatively short-lived pleasurable activity requiring little or no special training to enjoy it” (Stebbins, p. 53).

In this chapter, we also address the role of tourism (i.e., leisure travel). Tourism and leisure are not separate fields of study. Like leisure, tourism is also considered as a time free from (unpleasant) obligations. The significant difference however is that tourism takes place outside one’s normal environment; it includes at least one overnight stay elsewhere (UNWTO, 1995). Leisure and tourism can be conceptualized in such a way that a synthesized behavioral understanding of the two disciplines can be conceived (Moore, Cushman, & Simmons, 1995). In fact, tourism may be regarded as a specific form of leisure as the distinction between tourism and everyday life (i.e., leisure and work) is not as apparent as it perhaps once was; tourism has very much become an integral part of life (Larsen, 2008; McCabe, 2002). For instance, experiences that were once confined solely to tourism are now accessible in everyday life (Lash & Urry, 1994). Tourism is also becoming increasingly more important; the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) reports an average long-term growth rate of 4% in international tourist arrivals and predicts 1.6 billion international arrivals by the year 2020 (UNWTO, 2008). These numbers exclude domestic trips, which outnumber international trips by more than a factor of five (Peeters & Dubois, 2010).

Happiness

People use a variety of words to describe how well they are doing or feeling. Commonly used terms are “well-being,” “quality of life,” or “happiness.” All of these have different – but sometimes partly overlapping – meanings. Veenhoven (2000) proposed a classification based on two bipartitions; life “chances” and life “results” versus “outer” and “inner” qualities (see Scheme 11.1).

Meanings of the Word

The upper half of Scheme 11.1 presents two variants of potential quality of life. The outer qualities address the opportunities in one’s environment, whereas the inner qualities refer to the ability to exploit these. Veenhoven denotes the environmental chances by the term “livability” and the personal capacities by “life-ability.” Livability of the environment represents good living conditions. Quality of life, well-being, and welfare are commonly used terms for this top-left part of the quadrant. According to Veenhoven (2000, p. 6), “‘[l]ivability’ is a better word, because it refers explicitly to a characteristic of the environment and does not have the limited connotation of material conditions.” Life-ability of the person denotes how well individuals are equipped to cope with their life. Besides being referred to as well-being or quality of life, this top-right quadrant of Scheme 11.1 is also denoted as adaptive potential, health, efficacy, or potency. Life-ability is the main focus of positive psychological interventions.

The lower half of Scheme 11.1 addresses the quality of life with respect to its outcomes. Veenhoven named the external worth of life as “utility of life,” whereas the inner valuation is termed “appreciation of life.” Utility of life presumes higher values; it “represents the notion that a good life must be good for something more than itself” (Veenhoven, 2000, p. 7). Appreciation of life is about the inner outcomes of life, by which is meant the subjective appreciation of life. This has also been referred to as subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and happiness.

The main focus of current happiness research, and therefore this chapter, is on life satisfaction, which is defined as “the overall appreciation of one’s life as-a-whole” (Veenhoven, 1984). Four kinds of satisfaction can be distinguished (see Scheme 11.2).

Kinds of Satisfaction

The word “satisfaction” is used with differing meanings. The fourfold taxonomy presented in Scheme 11.2 helps us understand these differences. A passing satisfaction addressing a part of life is what we call a pleasure, for instance, the enjoyment derived from reading a good book or drinking a cold glass of beer. An enduring kind of satisfaction related to a part of one’s life is referred to as a part satisfaction, which can be satisfaction with a “domain” of life, such as leisure, or an “aspect” of life, such as the variety. A passing kind of satisfaction relating to one’s life as-a-whole is a poetic or religious type of extasis, an intense experience, which is called peak experience. Finally, life satisfaction (or happiness) is an enduring kind of satisfaction with life as-a-whole (Veenhoven, 2010a). The kinds of satisfaction addressed in this chapter are enduring kinds of satisfaction: part satisfaction (i.e., leisure satisfaction) and life satisfaction.

Components of Happiness

When estimating their satisfaction with life as-a-whole, people draw on two sources of information: how well they feel most of the time and to what extent their life meets their wants. Veenhoven (2009) refers to these appraisals as, respectively, the “affective” and “cognitive” components of happiness and considers these as subtotals in the inclusive evaluation of life, which he calls “overall happiness.” These appraisals do not necessarily coincide. For instance, one can feel good most on the time but still judge that life falls short of one’s aspirations.

Feelings, in terms of emotions, affect, and mood, belong to the affective component of happiness, called hedonic level of affect. Contentment is the term used to describe the cognitive component of happiness. Contentment designates “the degree to which an individual perceives that his aspirations are being met” (Veenhoven, 1984, p. 27).

In this chapter, we will address both overall happiness and the affective component (i.e., hedonic level of affect). We will not deal with the cognitive component of happiness because its relation with leisure has not been assessed empirically as of yet.

Measures of Happiness

Over the years, various methods of assessing happiness have been applied. According to Layard (2005), the most “objective” method of measuring happiness is by means of a brain scan. For rather obvious reasons, this is not a very useful method. Since happiness is something we have in mind, it can also be measured using self-reports.

Self-report questionnaires or diary studies are often used in empirical studies on happiness. An example of the latter is the experience sampling method (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1987), which is a method where participants are “beeped” on a PDA or cell phone and are asked to record where they are, what they are doing, and how they feel at multiple moments throughout a day, an ideal method to assess optimal experiences. An alternative form of a diary study is the day reconstruction method (DRM; Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004), in which respondents assess the previous day in its entirety. The most commonly used, however, are self-report questionnaires which may use single-item questions (Abdel-Khalek, 2006) or a variety of scales to assess happiness, such as the Positive And Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999), or the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Pavot & Diener, 1993). The PANAS and DRM measure the affective component of life satisfaction, whereas the SHS and SWLS are overall measures of happiness. The responses to self-report questions on happiness are generally prompt, nonresponse is low, and temporal stability is high (Veenhoven, 1984, 1991b).

Can Leisure Affect Happiness?

Some theories argue that happiness cannot be changed. For instance, homeostatic set point theory or trait theory argues that happiness is a rather stable “trait” and that whatever we do, we cannot change our happiness. In this view, particular experiences can at best provide a temporary uplift, after which we return to our set point (Cummins, 2005), and in that view, leisure will not make us any happier.

How about the reality value of this theory? One implication is that happiness remains about the same over the span of one’s life. This theory is partly based on Lykken and Tellegen’s (1996) findings on heredity of personality traits, which are indeed quite stable, particularly after the age of 30 (Costa & McCrae, 1994). Yet happiness appears to be a “state” rather than a “trait.” A research synthesis by Veenhoven (1994) showed that happiness is stable in the short run, but not over the lifetime. Furthermore, happiness is not insensitive to fortune or adversity, and the genetic base of happiness is modest at best. More recently, Headey (2008, 2010) showed that set point theory overstates the stability of happiness; some groups of people at least experience substantial permanent upward or downward changes in life satisfaction.

Comparison theory is a cognitive theory of happiness and holds that we base our happiness on the estimation of the gap between the realities of our lives and common standards of the good. Standards of comparison are deemed variable rather than fixed, and subjective evaluation of life is considered unrelated to the “objective” quality of life (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995). Comparison theory disregards the affective component (Veenhoven, 1991a; Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995). Cross-national research has failed to find evidence supporting the assumptions of comparison theory (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt), whereas research between groups of individuals (happy versus unhappy) has found evidence that supports comparison theory (Lyubomirsky & Ross, 1997). Comparison theory allows for an effect of leisure on happiness. Leisure participation, the way one spends their leisure time, and the time which is available for leisure could be part of comparison between individuals or groups of individuals within a particular society.

Other cognitive happiness theories, such as goal theory, also imply that leisure can influence happiness. Consumer behavior is predominantly goal-directed. A goal focuses on a specific outcome, but is not limited to such an outcome. Goals also encompass experiences and sequences of events (Bagozzi & Dholakia, 1999). Several studies in the field of happiness have shown that the pursuit of personal goals and progress on (important) goals are strong predictors of happiness (Brunstein, 1993; Emmons, 1986, 1992; Omodei & Wearing, 1990; Palys & Little, 1983). However, people may adopt certain goals which are not congruent with their needs (Diener, 2000), striving for such goals will not increase happiness. Similarly, Kasser and Ryan (1993) found that happiness does not increase when people make progress on certain goals, such as “making money.” Their interpretation is that certain goals meet intrinsic needs and those affect happiness, whereas others meet extrinsic needs and do not affect happiness. Additionally, McGregor and Little (1998) found that perceived efficacy is related to happiness. Low expectations of success are associated with negative affect (Emmons, 1986). Thus, in the case of leisure, striving for leisure goals which are congruent to an individual’s needs and wants should increase happiness. Like other cognitive happiness theories, goal theory ignores the affective component of happiness.

Livability theory or need theory is an affective theory of happiness which posits that the subjective appreciation of life is based on the “objective” quality of life. Livability theory focuses on absolute quality of living conditions, whereas comparison theory focuses on the relative difference. Thus, according to livability theory, people are happier in good living conditions compared to bad living conditions, even if they know that others are better off (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995). This theory presumes that there are basic human needs and that happiness increases when these needs are met (Diener & Lucas, 2000). In this view, happiness mirrors the degree to which innate needs are met (Veenhoven, 2009). Cross-national research supports the assumptions of livability theory (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt), particularly the relation between economic growth and its influence on years lived happily (Veenhoven & Hagerty, 2006). In this view, leisure can contribute to happiness if it is instrumental in meeting human needs. If so, people will be happier in societies that have cultivated leisure compared to societies that have not.

Diener and Lucas (2000) concluded that most of the aforementioned theories are not mutually exclusive and proposed an inclusive evaluation theory, which involves evaluating incoming information that is relevant to well-being. They argue that desires, goals, and needs are chronically salient standards and consequently have ongoing effects on happiness. Past comparison and social comparison are only relevant in evaluating one’s happiness in specific circumstances.

Thus, from a theoretical perspective, there are several ways in which leisure may contribute to happiness of individuals. Comparing one’s leisure time and activities to others who are better or off, or worse off, could affect happiness. Another possibility is to strive for goals, congruent with one’s needs. Pursuit and progress on these personal goals would positively affect happiness. Finally, when basic human needs are met to a great extent, this may allow for more leisure time and opportunities to spend this time according to one’s needs, which would be beneficial to individuals’ happiness.

How Personality Influences Leisure and Happiness

According to Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade (2005), approximately 50% of an individual’s happiness is predetermined through heredity, 10% is determined by circumstances, and 40% is affected by intentional activity. The domain of leisure falls within the 40% of the happiness spectrum which is affected by intentional activity. The 50% set point probably reflects, to a large degree, personality traits (McCrae & John, 1992), which are highly heritable (Tellegen et al., 1988), although there is reason to believe that this genetic set point is likely to be lower than 50% (Headey, 2008, 2010).

The five-factor model of personality (FFM or Big 5) is a “hierarchical organization of personality traits in terms of five basic dimensions: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience” (McCrae & John, 1992, p. 175). Even though the model is widely accepted, there remain disputes over the amount of factors (too few or too many) and the best interpretation of the factors (Becker, 1999). Quite possibly, there are other dimensions of personality not covered in the FFM.

The five traits are heritable (25–45%; Larsen & Buss, 2002). The highest degree of heritability is associated with extraversion and neuroticism (McCrae & John, 1992). Personality influences relationships, goal striving, and life events. Costa and McCrae (1994) found that personality traits are relatively stable after the age of 30, which has been confirmed by others (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999). The role of extraversion in regard to happiness has been researched extensively (Argyle & Lu, 1990b; Diener, Larsen, & Emmons, 1984; Diener, Sandvik, Pavot, & Fujita, 1992; Moskowitz & Cote, 1995; Pavot, Diener, & Fujita, 1990). The presence of positive affect is predominantly related to extraversion (Rusting & Larsen, 1997). These studies have concluded that extraverts are more sensitive to positive mood induction than introverts (Larsen & Ketelaar, 1991; Rusting & Larsen, 1997). Extraversion is related to positive affect through more indirect mechanisms (Argyle & Lu, 1990b; Pavot et al.), and extraverts are happier than introverts (Diener et al., 1992; Pavot et al.). Extraverts are more likely to be more involved with people and consequently have a greater circle of friends (Myers, 1993).

Personality traits not only influence happiness but also have an influence on how individuals make use of their leisure time (Hills & Argyle, 1998; Kraaykamp & Van Eijck, 2005; Melamed, Meir, & Samson, 1995). Kraaykamp and Van Eijck found that openness to experience has a positive effect on book reading and outdoor arts attendance. Openness to experience stimulates interest in complex and exciting recreational activities. Furthermore, they found that conscientiousness had a negative effect on participation in difficult or unconventional activities. Extraverts feel generally much better in high-stimulation situations. Although leisure situations are not necessarily more activating than work situations, extraverts tend to use their leisure time for more activating activities; extraversion is positively associated with leisure pursuits (Argyle & Lu, 1990a; Brandstätter, 1994; Hills & Argyle, 1998; Lu & Hu, 2005). Additionally, individuals who score high on extraversion have stronger social motives, which are more easily satisfied in leisure (Brandstätter, 1994). People who score high on extraversion and neuroticism also watch more TV soap operas (Hills & Argyle, 1998; Lu & Argyle, 1993).

As personality partially influences how leisure time is spent, it is important to find leisure activities which are congruent with one’s personality (i.e., leisure congruence). Leisure congruence is found to be positively associated with work satisfaction and negatively with burnout and somatic complaints. Individuals who selected congruent leisure activities had higher work satisfaction (31%), higher self-esteem (20%), less burnout (21%), fewer somatic complaints (17%), and less anxiety (17%) compared to those who lacked leisure congruence (Melamed et al., 1995).

In sum, personality has an influence on how individuals allocate their leisure time, and personality also partly determines how happy individuals are. Even though personality traits are highly heritable, there are still many opportunities for individuals to affect their happiness by finding leisure activities which are congruent with their needs.

Research Findings on Leisure and Happiness

Although leisure has been a frequent subject of empirical research (Stebbins, 2001), the relation between leisure and happiness has not received much attention to date. The available research results have been gathered in the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2010d). All the literature on this subject can be found in its Bibliography of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2010b), subject section Happiness and Leisure (code Le). By the end of 2010, there were 100 publications in this category. Findings yielded by studies that used acceptable measures of happiness are presented in the collection of correlational findings. One of the reports in this collection, “Happiness and Leisure” (code L3), contained 190 findings at the end of 2010 (Veenhoven, 2010c). We summarize the main findings in the following sections.

Work and Leisure

Work, leisure, and happiness are interrelated (Haworth, 1997). Leisure is used by individuals as an opportunity to cope with work stress (Trenberth, Dewe, & Walkey, 1999) and working conditions influence leisure satisfaction (Near, 1984). The passive aspects of leisure are well suited to cope with work stress (Trenberth et al.).

Loss of work is associated with lower life satisfaction as the unemployed are less happy than the employed (Böhnke & Kohler, 2008; Winkelmann & Winkelmann, 1998). Additionally, the unemployed are less happy about their home life (Fogarty, 1985), which is considered a part satisfaction (see Scheme 11.2). The effect of unemployment is three times stronger than that of bad health, and younger people are more strongly affected by unemployment (Winkelmann & Winkelmann).

Not only paid work is associated with happiness, volunteer work is associated with happiness as well (Boelhouwer & Stoop, 1999; Böhnke & Kohler, 2008; Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Happy individuals are more active in volunteering and additionally, volunteering adds to their happiness. Thus, there is evidence that there exists a positive cycle of selection and social causation processes (Thoits & Hewitt). Whether self-selection or social selection is the predominant factor in choosing to engage in volunteer work is unclear . Thoits and Hewitt argue that in some circumstances, it is likely that both these processes occur. All the findings on work and leisure, except where indicated, are based on measures of overall life satisfaction (bottom-right quadrant of Scheme 11.2).

Leisure Activities

Leisure activities can be either passive or active. For instance, watching a sports game on TV would be considered passive participation, whereas participating in a sports game would be considered active participation. Leisure activities produce positive moods, and much of this derived pleasure stems from the social relationships that they foster (Hills & Argyle, 1998). Participation in social activities is associated positively with happiness (Ragheb, 1993), and frequency of participation in leisure activities is also associated with happiness (Baldwin & Tinsley, 1988; Dowall, Bolter, Flett, & Kammann, 1988; Lloyd & Auld, 2002; Wankel & Berger, 1990). However, participants are not necessarily happier overall compared to nonparticipants. Churchgoers are happier than those who do not attend religious services (Böhnke & Kohler, 2008), although the frequency of church visits is not associated with happiness (Nawijn & Veenhoven, 2011).

All the aforementioned findings are about overall life satisfaction. Flow is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). A state of flow could be regarded as a peak experience (bottom-left quadrant in Scheme 11.2). Research on flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, 1990, 1998) finds that optimal experiences are most likely to occur during structured leisure activities and when reading (Della Fave & Massimini, 2003). Reading had been associated, in a positive way, with happiness by Ragheb (1993), but Nawijn and Veenhoven (2011) failed to find a significant association between frequency of reading and general life satisfaction. Watching TV generally relates negatively to overall happiness (Bruni & Stanca, 2006, 2008; Della Fave & Bassi, 2003; Frey, Benesch, & Strutzer, 2005). Still, TV watching is a source of pleasure (top-left quadrant in Scheme 11.2), though certainly not the most pleasurable activity. In their analysis of 21 different activities, Krueger et al. (2009) found that walking, making love, exercise, playing, and reading are the most enjoyed activities, in both their French and US samples. Least enjoyable activities were housework, travel, shopping, computer/email/Internet, taking care of one’s children (only in US sample), commuting, and working. Serious leisure (Stebbins, 2007), in the form of hobbies, is deemed particularly important for happiness. The limited data available on this subject suggest that people who have a hobby are happier than those who do not (Boelhouwer & Stoop, 1999).

The way in which leisure activities influence happiness is related to age or certain cohorts. Being active in later life is positively associated with overall life satisfaction (Nimrod, 2007). Social activities and travel are associated with happiness for those aged 65–74. Those aged 75 or older are the happiest, spending time with family and doing home-based activities (Kelly, Steinkamp, & Kelly, 1987).

Leisure Travel

Holiday trips potentially add to individuals’ happiness in several ways. Vacationing may have a direct effect on an individual’s happiness by anticipating a trip, which would allow for increased hedonic level of affect. Similarly, savoring the holiday experience through memories may induce an “afterglow” effect, which could cause higher post-trip levels of hedonic affect. Finally, during the trip itself, people feel supposedly better than they do in everyday life.

Individuals may also benefit from vacationing in a more indirect way by benefiting from impressions or skills learned while on vacation, for instance, having learned a language, understanding a culture, or having made new friends. Recuperation is also deemed an important vacationing benefit.

Recent research has mostly supported the direct way in which vacationing adds to individuals’ happiness (Boelhouwer & Stoop, 1999; De Bloom et al., 2010; Hagger, 2009; Nawijn, 2010; Nawijn, 2011 b; Nawijn, Marchand, Veenhoven, & Vingerhoets, 2010). For instance, people who had recently had a holiday trip score higher on overall happiness than those who did not (Boelhouwer & Stoop, 1999), which supports the afterglow hypothesis. However, increased levels of post-trip happiness seem to be the exception rather than the rule. Only those who have a stress-free holiday benefit – in terms of hedonic level of affect – from such afterglow effects and only for 2 weeks (Nawijn et al.). Vacationers anticipating holidays strongly score higher in overall happiness and hedonic level of affect than those who anticipate holidays to a lesser extent (Hagger, 2009). Vacationers also experience higher levels of hedonic level of affect than non-vacationers several weeks before the trip starts (Nawijn et al.). While on holiday, vacationers are generally in a good mood (Nawijn, 2010), which is much better than their mood in everyday life (De Bloom et al.; Nawijn, 2011). The long-term effect of vacationing on overall happiness and hedonic level of effect is virtually nonexistent (Nawijn, 2011a).

Leisure Satisfaction

Ateca-Amestoy, Serrano-del-Rosal, & Vera-Toscano (2008, p. 65) define leisure satisfaction as follows (based on Beard and Ragheb (1980)): “positive perceptions or feelings that an individual forms, elicits, or gains as a result of engaging in leisure activities and choices. It is the degree to which one is presently content or pleased with one’s general leisure experiences and situations. This positive feeling of pleasure results from the satisfaction of felt or unfelt needs of the individual.” Satisfaction with leisure appears to be positively associated with happiness (Ateca-Amestoy, et al., 2008; Lloyd & Auld, 2002; Ragheb, 1993; Spiers & Walker, 2009).

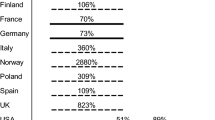

Satisfaction of life domains correlates fairly strongly with life satisfaction (Ateca-Amestoy et al., 2008; Lloyd & Auld, 2002; Van Praag & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, 2004; Van Praag, Frijters, & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, 2003). Part satisfactions (see Scheme 11.2) of finance, health, job, and leisure are the four most important correlates with life satisfaction in Germany (Van Praag et al.). The strength of the effects varies among workers and nonworkers and between East and West Germany, with western nonworkers scoring highest.

Conclusion

Casual leisure and leisure travel typically provide temporary happiness boosts which are the strongest in the moment itself. In the case of leisure travel, vacationers are happier on holiday compared to everyday life. Little is known about project-based leisure and serious leisure; the limited data and theoretical assumptions suggest a positive effect on happiness.

Agenda for Future Research

Research in the relation between leisure and happiness is still in its infancy, and there is a dire need for future research. We present a brief overview of themes for further investigation.

Beyond Casual Leisure

The studies to date have focused mostly on what Stebbins (2001, 2007) refers to as casual leisure. Little or no research has been undertaken in the areas of project-based leisure and serious leisure. Within leisure travel research, the focus has been on the direct effects of vacationing, not on the possible indirect effects. Project-based leisure and serious leisure may add to happiness through goal striving. A hobby or a project seems particularly suited to work on goals. A project is essentially a goal in itself. On top of that, projects and serious leisure activities generally last longer than leisure travel or casual leisure. The outcome of future studies on project-based leisure and serious leisure and their effect on happiness could therefore be quite promising.

Specification

The question is not so much whether leisure adds to happiness, but what kinds of people benefit most from what kinds of leisure. Effects of leisure are probably not the same for the young and the old or for singles and couples. Specification is not only of interest to the leisure industry, but it is also in the interest of consumers. This kind of research requires large samples, and it is necessary that different populations are involved. In this context, we note that the available data mainly draw on samples in rich countries. Little is known about the importance of leisure and the allocation of free time in less developed countries and its relation to happiness.

Cause and Effect

Since most existing studies are cross-sectional, we are inadequately informed about causality. There is a dearth of research on the effects of happiness in leisure preferences and behavior, and we are also largely in the dark about causal mechanisms. Follow-up studies are needed for that purpose, preferably long-term follow-up studies that also involve personal characteristics, such as personality and health. Since such follow-up studies are very expensive, it is wise to join forces with existing panels, such as the German Socio-Economic Panel or the Happiness Monitor (Oerlemans, 2009).

Test of Theories

Lastly, happiness theories should be tested in a leisure context. Sirgy (2010) recently proposed a research agenda for goal striving in relation to leisure travel. The hypotheses that he proposed can be tested within other leisure domains as well. Additionally, comparison and need theories lend themselves for (further) testing in studies on leisure.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006). Measuring happiness by a single item scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(2), 139–150.

Argyle, M., & Lu, L. (1990a). Happiness and social skills. Personality and Individual Differences, 11(12), 1255–1261.

Argyle, M., & Lu, L. (1990b). The happiness of extraverts. Personality and Individual Differences, 11(10), 1011–1017.

Ateca-Amestoy, V., Serrano-del-Rosal, R., & Vera-Toscano, E. (2008). The leisure experience. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(1), 64–78.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Dholakia, U. M. (1999). Goal setting and goal striving in consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing, 63, 19–33.

Baldwin, K., & Tinsley, H. (1988). An investigation of the validity of Tinsley and Tinsley’s (1986) theory of leisure experience. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35(3), 263–267.

Beard, J. G., & Ragheb, M. G. (1980). Measuring leisure satisfaction. Journal of Leisure Research, 12(1), 20–33.

Becker, P. (1999). Beyond the big five. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(3), 511–530.

Bergsma, A. (2008). Do self-help books help? Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 341–360.

Boelhouwer, J., & Stoop, I. (1999). Measuring well-being in the Netherlands. Social Indicators Research, 48(1), 51–75.

Böhnke, P., & Kohler, U. (2008). Well-being and inequality (WZB Discussion Paper No. SP I 2008-201). Berlin, Germany: WZB.

Brandstätter, H. (1994). Pleasure of leisure-pleasure of work: Personality makes the difference. Personality and Individual Differences, 16(6), 931–946.

Bruni, L., & Stanca, L. (2006). Income aspirations, television and happiness: Evidence from the world values survey. Kyklos: internationale Zeitschrift für Sozialwissenschaften, 59(2), 209–226.

Bruni, L., & Stanca, L. (2008). Watching alone: Relational goods, television and happiness. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 65(3), 506–528.

Brunstein, J. C. (1993). Personal goals and subjective well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 1061–1070.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1994). Set like plaster? Evidence for the stability of adult personality. In T. F. Heatherton & J. L. Weinberger (Eds.), Can personality change? (pp. 21–40). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The experience of play in work and games. San Francisco, CA/Washington, DC/London: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1998). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (1987). Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175(9), 526–536.

Cummins, R. A. (2005). Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(10), 699–705.

Danner, D. D., Snowdon, D. A., & Friesen, W. V. (2001). Positive emotions in early life and longevity: Findings from the nun study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(5), 804–813.

De Bloom, J., Geurts, S. A. E., Taris, T. W., Sonnentag, S., De Weerth, C., & Kompier, M. A. J. (2010). Effects of vacation from work on health and well-being: Lots of fun, quickly gone. Work and Stress, 24(2), 196–216.

Della Fave, A., & Bassi, M. (2003). Italian adolescents and leisure: The role of engagement and optimal experience. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 99, 79–94.

Della Fave, A., & Massimini, F. (2003). Optimal experience in work and leisure among teachers and physicians: Individual and bio-cultural implications. Leisure Studies, 22(4), 323–342.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43.

Diener, E., Larsen, R. J., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). Person X situation interactions: Choice of situations and congruence response models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(3), 580–592.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2000). Explaining differences in societal levels of happiness: Relative standards, need fulfillment, culture, and evaluation theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 41–78.

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Pavot, W., & Fujita, F. (1992). Extraversion and subjective well-being in U.S. national probability sample. Journal of Research in Personality, 26(3), 205–215.

Dowall, J., Bolter, C., Flett, R., & Kammann, R. (1988). Psychological well-being and its relationship to fitness and activity levels. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 14(1), 39–45.

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(5), 1058–1068.

Emmons, R. A. (1992). Abstract versus concrete goals: Personal striving level, physical illness, and psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(2), 292–300.

Fogarty, M. (1985). British attitudes to work. In M. Abrams, D. Gerard, & N. Timms (Eds.), Values and social change in Britain (pp. 173–206). London: Macmillan.

Frey, B. S., Benesch, C., & Strutzer, A. (2005). Does watching TV make us happy? Zurich, Switzerland: Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich.

Hagger, J. C. (2009). The impact of tourism experiences on post retirement life satisfaction. Adelaide, Australia: The University of Adelaide.

Haworth, J. T. (1997). Work, leisure and well-being. London/New York: Routledge.

Headey, B. (2008). The set-point theory of well-being: Negative results and consequent revisions. Social Indicators Research, 85(3), 389–403.

Headey, B. (2010). The set point theory of well-being has serious flaws: On the eve of a scientific revolution? Social Indicators Research, 97(1), 7–21.

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (1998). Positive moods derived from leisure and their relationship to happiness and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(3), 523–535.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science, 306(5702), 1776–1779.

Kahneman, D., Wakker, P. P., & Sarin, R. (1997). Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 375–405.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422.

Kelly, J. R., Steinkamp, M. W., & Kelly, J. R. (1987). Later-life satisfaction: Does leisure contribute? Leisure Sciences, 9(1), 189–200.

Kraaykamp, G., & Van Eijck, K. (2005). Personality, media preferences, and cultural participation. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1675–1688.

Krueger, A. B., Kahneman, D., Fischler, C., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2009). Time use and subjective well-being in France and the U.S. Social Indicators Research, 93(1), 7–18.

Larsen, J. (2008). De-exoticizing tourist travel: Everyday life and sociality on the move. Leisure Studies, 27(1), 21–34.

Larsen, R. J., & Buss, D. V. (2002). Personality psychology, domains of knowledge about human nature. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Larsen, R. J., & Ketelaar, T. (1991). Personality and susceptibility to positive and negative emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 132–140.

Lash, S., & Urry, J. (1994). Economies of signs and space. London: Sage.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. London: Allen Lane.

Lloyd, K., & Auld, C. J. (2002). The role of leisure in determining quality of life: Issues of content and measurement. Social Indicators Research, 57(1), 43–71.

Lu, L., & Argyle, M. (1993). TV watching, soap opera and happiness. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 9, 501–507.

Lu, L., & Hu, C.-H. (2005). Personality, leisure experiences and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(3), 325–342.

Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7(3), 186–189.

Lyubomirsky, S., & King, L. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Ross, L. (1997). Hedonic consequences of social comparison: A contrast of happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(6), 1141–1157.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131.

McCabe, S. (2002). The tourist experience and everyday life. In G. M. S. Dann (Ed.), The tourist as a metaphor of the social world (pp. 61–77). Wallingford, CT: CABI.

McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215.

McGregor, I., & Little, B. R. (1998). Personal projects, happiness, and meaning: On doing well and being yourself. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 494–512.

McMahon, D. M. (2006). Happiness: A history. New York: Grove.

Melamed, S., Meir, E. I., & Samson, A. (1995). The benefits of personality-leisure congruence: Evidence and implications. Journal of Leisure Research, 27(1), 25–40.

Moore, K., Cushman, G., & Simmons, D. (1995). Behavioral conceptualization of tourism and leisure. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 67–85.

Moskowitz, D. S., & Cote, S. (1995). Do interpersonal traits predict affect? A comparison of three models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 915–924.

Myers, D. G. (1993). The pursuit of happiness: Discovering the pathway to fulfillment, well-being, and enduring personal joy. New York: Avon Books.

Nawijn, J. (2010). The holiday happiness curve: A preliminary investigation into mood during a holiday abroad. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(3), 281–290.

Nawijn, J. (2011a). Determinants of Daily Happiness on Vacation. Journal of Travel Research, 50(5), 559–566

Nawijn, J. (2011b). Happiness through Vacationing: Just a Temporary Boost or Long-Term Benefits? Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(4), 651–665.

Nawijn, J., Marchand, M., Veenhoven, R., & Vingerhoets, A. (2010). Vacationers happier, but most not happier after a holiday. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 5(1), 35–47.

Nawijn, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2011). The effect of leisure activities on life satisfaction: The importance of holiday trips. In I. Brdar (Ed.), The human pursuit of well-being: A cultural approach (pp. 39–53). Dordrecht, the Netherlands/Heidelberg, Germany/London/New York: Springer.

Near, J. P. (1984). A comparison of work and nonwork predictors of life satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 27(1), 184–190.

Nimrod, G. (2007). Expanding, reducing, concentrating and diffusing: Post retirement leisure behavior and life satisfaction. Leisure Sciences, 29(1), 91–111.

Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2009). Geluksdagboek (Happiness Diary). Extended Version of the Happiness Monitor: Program for Online Assesment of Daily Activity, Social Interactions, Place and Happiness. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Omodei, M. M., & Wearing, A. J. (1990). Need satisfaction and involvement in personal projects: Toward an integrative model of subjective well-being among men and women. Personality and Individual Differences, 5(4), 533–539.

Palys, T. S., & Little, R. R. (1983). Perceived life satisfaction and organization of personal project system. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 1221–1230.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 5(2), 164–172.

Pavot, W., Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1990). Extraversion and happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 11(12), 1299–1306.

Peeters, P., & Dubois, G. (2010). Tourism travel under climate change mitigation constraints. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 447–457.

Ragheb, M. G. (1993). Leisure and perceived wellness: A field investigation. Leisure Sciences, 15(1), 13–24.

Rusting, C. L., & Larsen, R. J. (1997). Extraversion, neuroticism, and susceptibility to positive and negative affect: A test of two theoretical models. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(5), 607–612.

Seligman, M., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421.

Sirgy, M. J. (2010). Toward a quality-of-life theory of leisure travel satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 49(2), 246–260.

Soldz, S., & Vaillant, G. E. (1999). The big five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 208–232.

Spiers, A., & Walker, G. J. (2009). The effects of ethnicity and leisure satisfaction on happiness, peacefulness, and quality of life. Leisure Sciences, 31(1), 84–99.

Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Serious leisure. Society, 38(4), 53–57.

Stebbins, R. A. (2007). Serious leisure: A perspective for our time. New Brunswick, NJ/London: Transaction Publishers.

Tellegen, A., Lykken, D., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., Segal, N. L., & Rich, S. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1031–1039.

Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), 115–131.

Trenberth, L., Dewe, P., & Walkey, F. (1999). Leisure and its role as a strategy for coping with work stress. International Journal of Stress Management, 6(2), 89–103.

UNWTO. (1995). Collection of tourism expenditure statistics (Technical Manual No. 2). Madrid, Spain: World Tourism Organization.

UNWTO. (2008). Tourism market trends 2006: World overview and tourism topics (No. 2006 ed.). Madrid, Spain: UNWTO

Van Praag, B. M. S., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified: A satisfaction calculus approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Praag, B. M. S., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(1), 29–49.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer.

Veenhoven, R. (1991a). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34.

Veenhoven, R. (1991b). Questions on happiness. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective wellbeing, an interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 7–26). London: Pergamon Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1994). Is happiness a trait? Tests of the theory that a better society does not make people any happier. Social Indicators Research, 32(2), 101–160.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life: Ordering concepts and measures of the good life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1(1), 1–39.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 449–469.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). How do we assess How happy we are? Tenets, implications and tenability of three theories. In A. K. Dutt & B. Radcliff (Eds.), Happiness, economics and politics: Towards a multidisciplinary approach (pp. 45–69). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elger Publishers.

Veenhoven, R. (2010a). Capability and happiness: Conceptual differences and reality links. Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 344–350.

Veenhoven, R. (2010b). World database of happiness, bibliography. Erasmus University Rotterdam. Available at: http://Worlddatabaseofhappiness.Eur.Nl. Accessed 21 Dec 2010.

Veenhoven, R. (2010c). World database of happiness, collection of correlational findings. Finding Report ‘Happiness and Leisure’, Subject Code L3, Erasmus University Rotterdam. Available at: http://Worlddatabaseofhappiness.Eur.Nl. Accessed 21 Dec 2010.

Veenhoven, R. (2010d). World database of happiness. Erasmus University Rotterdam. Available at: http://Worlddatabaseofhappiness.Eur.Nl. Accessed 21 Dec 2010.

Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34(1), 33–68.

Veenhoven, R., & Hagerty, M. R. (2006). Rising happiness in nations 1946–2004: A reply to Easterlin. Social Indicators Research, 79(3), 421–436.

Wankel, L., & Berger, B. (1990). The psychological and social benefits of sport and physical activity. Journal of Leisure Research, 22(2), 167–182.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica, 65(257), 1–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nawijn, J., Veenhoven, R. (2013). Happiness Through Leisure. In: Freire, T. (eds) Positive Leisure Science. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5058-6_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5058-6_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-5057-9

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-5058-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)