Abstract

‘Greening in the red zone’ refers to post-catastrophe, community-based stewardship of nature, and how these often spontaneous, local stewardship actions serve as a source of social-ecological resilience in the face of severe hardship. In this introductory chapter, we provide the reader with the fundamentals needed to understand our argument for why and how greening in the red zone occurs and to what end. We begin with a brief introduction to the terms ‘greening’, ‘red zone’, and ‘resilience’. We then briefly introduce the two types of evidence presented in this book. First are explanations from a large body of research on the impacts of both passive contact with, and active stewardship of, nature, and from a growing network of social and ecological resilience scholars who subscribe to the notion that change is to be expected and planned for, and that identifying sources of resilience in the face of change—including the ability to adapt and to transform—is crucial to the long-term well-being of humans, their communities, and the environment. The second source of evidence are the long and short descriptions of greening in red zones from post-disaster and post-conflict settings around the world, ranging from highly visible and symbolic initiatives like the greening of the Berlin Wall, to smaller-scale efforts such as planting a community garden in a war zone. We summarize the research-based explanations and long and short case descriptions of greening in the red zone in three tables at the end of this chapter.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Co-editors Keith Tidball and Marianne Krasny state the thesis underlying the chapters of this book: the actions of humans to steward nature can be a source of individual, community, and social-ecological system resilience in chaotic post-disaster or post-conflict settings. After defining ‘greening’, ‘red zone’, and ‘resilience’, Tidball and Krasny introduce the theoretical and case description evidence for their thesis.

The Argument

Rising above the seemingly endless expanse of townships surrounding Johannesburg South Africa is the Soweto Mountain of Hope. During the turbulent years at the end of the apartheid era, this hill was a symbol of the violence brought about by ethnic conflict and hatred. Residents who ventured into this unmanaged landscape were subject to muggings and even murder by thugs concealed among the shrubs. ‘Necklacing’, in which victims were forced into the center of a tire and then set on fire as a form of punishment or reprisal, was not uncommon. Footnote 1

After the collapse of the apartheid government, the hillside took on a different meaning. When we first visited in 2006, we were told the story of community leaders working with local residents to transform the hill into a site for renewal—renewal of the residents, of the community, and of the landscape. We were told about a dead tree from which 15 old tires and items of rubbish were said to be hanging. We heard how this symbolic dead tree was called ‘The Tree of Life’ because residents of Soweto believed that the dead wood shows how humans have destroyed the earth and the tires and rubbish show the means by which we have done so. The 15 tires, we heard, represent the 15 men hanged from the tree when it was living. They also represent the truly awful manner of their deaths, the aforementioned necklacing. Yet, through community members memorializing with metaphors, as well as through planting vegetable plots and gardens in memory of AIDS victims, inviting the public to install art objects telling the story of their struggle, and hosting drumming circles, cooking classes, and other community events, the site was transformed physically—and symbolically. It became a Mountain of Hope in South Africa’s largest township.

The story of the Soweto Mountain of Hope is retold in this book in a short chapter by Soul Shava and the community leader who spearheaded the transformation, Mandla Mentoor. This story is one of many that are emerging from communities around the world. Stories of people who turn to greening during the most difficult of times—periods of violent conflict and of collapse of the social and economic fabric of their community, and in the aftermath of earthquakes, hurricanes, and other human-natural disasters. This book has brought together these stories in a series of short examples and longer case studies. We also have sought to understand why people turn to greening in the face of conflict and disaster. What motivates them, and what are the implications for themselves, their community, and their local environment? In so doing, we have turned to explanations from a growing body of research on the impacts of more passive contact with nature, as well as a smaller literature on the outcomes of the act or active practice of nature stewardship. We also have drawn on a growing network of ‘resilience scholars’–social and ecological scientists who subscribe to the notion that change is to be expected and planned for, and that identifying sources of resilience in the face of change—including the ability to adapt and to transform—is crucial to the long-term well-being of humans, their communities, and the local environment.

According to resilience scholars Masten and Obradovic (2008), ‘It is often argued that ‘all disasters are local’ (Ganyard 2009), at least in the short term. In the same sense, it could be said that all human resilience is local, emerging from the actions of individuals and small groups of people, in relation to each other and powered by the adaptive systems of human life and development’. Heeding these words, this book starts with phenomena that take place at local levels—the small acts of greening that emerge, often spontaneously, following disaster. However, this is not to say that the questions addressed by the authors in this volume are irrelevant for government policy makers, larger non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and researchers working in the areas of natural resources management and peacemaking. To the contrary, taken as a whole, the theoretical and practical contributions of this book make an argument for why policy makers should take into account these local acts of greening or small-scale ‘sources of resilience’—an argument that we return to in the final chapter.

How might local greening practices become a source of resilience during difficult times? Although much of our thinking about individuals who have experienced catastrophe focuses on suffering and despair, studies have shown that not only are resilient people buffered from depression by positive emotions, they actually thrive through such emotions. To quote one such research paper, ‘finding positive meaning may be the most powerful leverage point for cultivating positive emotions during times of crisis’ (Fredrickson et al. 2003).

In a foundational chapter (Tidball, Chap. 4, this volume), this book argues that we should pay attention to the use of the term ‘cultivating’ in Frederickson’s writing. It makes the connection between cultivating positive emotions and cultivating plants, and suggests that the act of greening integrates both. As stated by Tidball, a series of ‘provocative studies provide an intriguing context and ‘jumping-off’ point for investigating the role not just of viewing or being around trees and green spaces, but also of cultivating such spaces. By cultivating, we refer to nurturing plants and animals, people and communities’.

Thus, the evidence accumulated in this edited volume focuses on community greeners (the people) and community greening (the practice), as well as the community green spaces these people and practices create (the places). The authors answer questions about the role of ‘greening’ people, practice, and places in building and demonstrating resilience in the face of catastrophic change. They explore how the act of people coming together around the renewal and stewardship of nature might enhance individual and community resilience, and perhaps even contribute to social-ecological system (SES) resilience, Footnote 2 in chaotic post-disaster and post-conflict contexts. Because of the rapid growth of cities globally and their ever looming importance as sites of conflict and disaster, many of the case studies are from urban settings (e.g., the Berlin Wall, New Orleans post-Katrina, Monrovia after the Liberian civil war), although more rural (e.g., Korean village groves, community-based wildlife and park management in Kenya and Afghanistan), and region-wide examples (e.g., Cyprus Red Line, Korean Demilitarized Zone) also are included.

In this book, we refer to post-catastrophe, community-based stewardship of nature that serves as a source of social-ecological resilience as ‘greening in red zones’. We turn now to a brief introduction to the terms ‘greening’, ‘red zone’, and ‘resilience’. The next chapter delves more deeply into resilience scholarship as it relates to disaster. The notions of greening and red zones are examined and illustrated in-depth throughout the remaining chapters of this book.

Greening

While recognizing the importance of green political thought Footnote 3 and of a growing interest in a ‘green economy’ (Pearce et al. 1992; Milani 2000), in this volume we focus on green initiatives that emerge in a context of self-organized community development and community-based natural resources management. In fact, perhaps a significant accomplishment of such grassroots greening practices, in particular the more participatory or activist forms embodied in many community gardens in New York and other large cities (Schmelzkopf 1995; Saldivar and Krasny 2004) and in tree-planting efforts in neighborhoods of post-Katrina New Orleans (Tidball et al. 2010; see also Tidball, Chap. 20, this volume), is the steady and growing mainstream acceptance of much of what was once fringe green political thought. The philosopher Andrew Light (2003) has captured this notion in his description of how grassroots environmental stewardship efforts in cities are defining a new environmental movement; this civic environmental movement finds its inspiration in the work of urban ‘community greeners’.

For the purposes of this book, we will not be dealing in much depth or detail with political or philosophical dimensions of greening. Nor will this book delve solely or too deeply into the broad field of horticulture, which concerns itself with growing plants in cities for ornamentation and other purposes (Tukey 1983). Rather than focus strictly on utilization of plants, we emphasize their active cultivation within a social-ecological or community context. And we go beyond the ornamental uses of plants and nature to suggest that human relationships with plants, animals, and landscapes have a role to play in urban and other settings faced with disaster and conflict.

Thus, we operationalize greening as an active and integrated approach to the appreciation, stewardship and management of living elements of social-ecological systems. Greening takes place in cities, towns, townships and informal settlements in urban and peri-urban areas, and in the battlefields of war and disaster. Greening sites vary—from small woodlands, public and private urban parks and gardens, urban natural areas, street tree and city square plantings, botanical gardens and cemeteries, to watersheds, whole forests and national or international parks. Greening involves active participation with nature and in human or civil society (Tidball and Krasny 2007)—and thus can be distinguished from notions of ‘nature contact’ (Ulrich 1993) that imply spending time in or viewing nature, but not necessarily active stewardship. The writers of this book explore how greening can enable or enhance recovery from disaster or conflict in situations where community members actively participate in greening, which in turn results in measurable benefits for themselves, their community, and the environment.

Whereas greening is a foundation of this book, several authors include other examples of active engagement with nature. For example, the short chapter by Smallwood describes the beginnings of civic engagement in helping to form and maintain a national park in Afghanistan, and the chapter by Krasny and colleagues includes examples of war veterans initiating hunting and fishing programs to help their fellow soldiers heal from the scars of war. And the chapter by Geisler describes how throughout multiple periods in history, governments have used greening, in the form of granting land rights to soldiers and settlers, for purposes of colonization. What unites all the chapters is a focus on efforts that have emerged in response to conflict and disaster, and that involve greening or other engagement in nature that integrates a community or civic, or in a few cases political, purpose.

Red Zones

The term ‘red zone’ has a history dating back to at least the first part of the twentieth century. One of its first usages was in reference to the ‘Zone rouge’ (French for Red Zone), the name given to 465 square miles of northeastern France that were destroyed during the First World War (Clout 1996; Smith and Hill 1920). In more recent times, the term has been used to refer to unsafe areas in Iraq after the 2003 invasion of the US and its allies, the opposite of ‘Green Zone’, a presumably more safe area in Iraq. The term was also used by journalist Steven Vincent, Footnote 4 as part of the title of his book In the Red Zone: A Journey Into the Soul of Iraq (2004), and has been used by others to describe lawless conditions such as those of the Rwandan genocide. Footnote 5

An internet search for ‘red zone’ illuminates how the term is currently used in film and digital entertainment media to connote a war zone, a hostile zone, a contaminated zone, or a zone characterized by increased intensity and higher stakes, such as in the combative sport American football. The term has also been used to describe the disorientation phase in a second order learning process documented and conceptualized in a learning process model among adults (Taylor 1986). For our purposes, we use the term red zone to refer to multiple settings (spatial and temporal) that may be characterized as intense, potentially or recently hostile or dangerous, including those in post-disaster situations caused by natural disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes, as well as those associated with terrorist attacks and war.

Within these red zones are people for whom the red zone represents a perturbation or disruption of their individual, family, and community patterns of living. For a herder in rural Afghanistan, a soldier occupying the herder’s village, or a relief worker from an NGO, red zones represent both a time period and points on a landscape where ecological and social forces are disturbed suddenly, drastically, and with little warning. These situations are referred to as Stability, Security, Transition and Reconstruction (SSTR) contexts by aid, diplomacy, and military organizations. According to the US Department of Defense (2005):

…the immediate goal [in SSTR activities] is to provide the local populace with security, restore essential services, and meet humanitarian needs. The long-term goal is to help develop indigenous capacity for securing essential services, a viable market economy, rule of law, democratic institutions, and a robust civil society. Tasks include helping rebuild indigenous institutions including various types of security forces, correctional facilities, and judicial systems necessary to secure and stabilize the environment; reviving or building the private sector, including encouraging citizen-driven, bottom-up economic activity and constructing necessary infrastructure; and developing representative governmental institutions (pp. 2–3).

The chapters in this book suggest that those involved in SSTR go beyond their usual strategies to consider the question: ‘How might greening play a role alongside other interventions in transforming red zones so that they become more secure, provide essential services, and meet humanitarian needs?’ The chapter by Tidball entitled ‘Urgent Biophilia’ even goes so far as to suggest that a connection to nature as expressed in the act of greening may be an essential human need for some disaster survivors. In an important complement to the notion of urgent biophilia, the chapter by Stedman and Ingalls on topophilia considers people’s greening reaction when a place they have learned to identify with is threatened by conflict. Whereas Chap. 2 (Resilience and Transformation in the Red Zone) presents evidence that providing spaces for individuals and communities to engage in greening will contribute to a community’s ability to adapt and transform in the face of disaster, the final chapter more directly addresses SSTR concerns in arguing that providing opportunities for expressing this need to be in, and to steward, nature may contribute to stability and order post-conflict.

Resilience

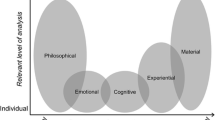

The contributors to this volume use the term resilience in multiple ways. Chapter authors Wells, Chawla, Helphand, and Winterbottom are primarily concerned with human resilience, i.e., the ability of individuals to maintain a stable equilibrium or to adapt in the face of trauma, loss, or adversity (Luthar et al. 2000; Bonanno 2004). The chapter by Okvat and Zautra adds to a discussion of human resilience the notion of community resilience, which is defined as a process facilitating the capacities existing in a community to contribute positively to functioning and adaptation after a disturbance (Norris et al. 2008, 131). The chapter by Tidball about community forestry in New Orleans focuses on resilience at the level of urban neighborhood social-ecological systems; it considers the interplay between disturbance, such as that represented in red zones, and renewal or reorganization of the broader social-ecological system through trees and tree meanings. Finally, a discussion of the term resilience would be incomplete without consideration of its use as a metaphor (Pickett et al. 2004); resilience as a metaphor across multiple levels of organization helps us to imagine the capacity not only to withstand or adapt to hardship, but also the possibility to transform into something better, stronger, and more flexible. Because resilience is foundational to a discussion of greening in the red zone, we devote an entire chapter to a discussion of its implications for disaster and conflict, with a focus on social-ecological systems resilience (see Tidball and Krasny, Chap. 2, this volume).

Scholars writing about social-ecological systems (SES) resilience have identified four factors as critical to fostering resilience during periods of change and reorganization: (1) learning to live with change and uncertainty; (2) nurturing biological and cultural diversity; (3) combining different types of knowledge for learning; and (4) creating opportunity for self-organization (Folke et al. 2002). In previous work we have proposed the term ‘civic ecology’ and associated ‘civic ecology practices’ (Tidball and Krasny, 2007; Krasny and Tidball 2010; Krasny and Tidball 2012) to describe community-based greening efforts such as those portrayed in the case studies and short chapters in this volume, which address these and other factors fostering SES resilience. We define civic ecology as the study of feedbacks and other interactions among four components of a SES: (1) community-based environmental stewardship (civic ecology practice); (2) education and learning situated in these practices (civic ecology education); (3) the people and institutions involved; and (4) the ecosystem services produced by the people, their stewardship, and educational practices (Tidball and Krasny 2007, 2011). Civic ecology practices integrate local stewardship activities, such as planting community gardens or monitoring local biodiversity, with learning from multiple forms of knowledge including that of community members and scientists or other experts. Such practices often lead to civic activism such as advocating for green spaces as a means to reduce crime and violence. Within the context of resilience, the goal of the study of civic ecology is to understand how people organize, learn, and act in ways that increase their capacity to withstand, and where appropriate to grow from, change and uncertainty, through nurturing cultural and ecological diversity, through creating opportunities for civic participation and self-organization, and through fostering learning from different types of knowledge. From the perspective of greening in the red zone, civic ecology emphasizes creating conditions whereby existing community assets can be leveraged to foster SES resilience prior to and following disaster or conflict in cities and in other SES.

The SES resilience literature seeks to understand not only the dynamics of disturbance and reorganization within any one system or scale of organization (e.g., individual, community, SES) but also feedbacks and other interactions across systems and scales (Gunderson and Holling 2002). Drawing from the authors of this book, we can imagine resilient individuals who display positive emotions by leading a community effort to plant and care for trees damaged in a hurricane. As they work together, these residents build community capacity and the trees they care for foster a more resilient local ecosystem relative to the devastated state that followed the hurricane. The trees and the planting activities create opportunities for others to experience positive emotions, which can foster another cycle of resilience. Such trees and planting activities also may become symbolic of resilience at larger scales, such as is the case with the trees that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, along with the subsequent reforestation efforts described in the chapter by Chen and McBride (Chap. 18).

Returning to Masten and Obradovic’s (2008) argument that human resilience to disasters emerges from the actions of local individuals and small groups of people, and to the notion that processes inherent to resilience cross scales or levels of organization, what then is the role of government, non-profit organizations, and other institutions that may have more far-reaching impacts than the local efforts described in many of the chapters in this volume? According to Masten and Obradovic (2008), ‘Larger systems facilitate this resilience, but are not likely to be directly available during an unfolding disaster on the scale of a flu pandemic or unfolding natural disaster, when some key communication, transportation, manufacturing, and other systems are likely to be disrupted or destroyed (Longstaff 2005). However, macrosystems such as governments, markets, media, and religions do have a functional presence in the expectations, values, hopes, training, and knowledge that individuals and local families in communities carry with them all the time, particularly in their memories and know-how’. This is reflected in the concept of environment shaping (Weinstein and Tidball 2007; Tidball and Weinstein 2011) where it is acknowledged that two important shifts in thinking in disaster and conflict response contexts have recently occurred: that asset-based participation is required, and that we must account for (usually perception-driven) self-reinforcing growth trends, or positive feedback loops.

In describing how local and regional self-organized greening efforts can become a source of resilience in post-disaster settings, the chapters of this book provide food for thought for the defense, security, development and relief, and other policy communities. Red zones are examples of where catastrophic changes have occurred and the SES has moved or is moving into a new, less desirable state. SSTR professionals, concerned with how one returns the system to an orderly state, often impose interventions that are directed from above or from outside local communities (Weinstein and Tidball 2007). Scholars studying resilience in SES are more apt to explore how self-organized efforts, or initiatives that emerge from local communities, aid in the process of moving beyond an orderly state to one that has a number of attributes that predict its ability to adapt and renew in the face of further change and disturbance. How to bring these two perspectives together is explored in the final chapter of this book.

About This Book

The goal of this book is to explore how the actions of humans to steward nature become a source of individual, community, and SES resilience in chaotic post-disaster or post-conflict settings. On a more theoretical level, the chapters in this book address several gaps in the resilience literature, including the lack of studies focused on cultural systems (Wright and Masten 2005), as well as the striking absence of ‘work that embeds human development in ecosystems that include interactions among species and nonhuman systems’ and that integrates the theory and science of individual human resilience with broader ecological systems theory and research exemplified by the SES resilience scholarship (Masten and Obradovic 2008).

This book is not intended to be the answer or the proverbial silver bullet for post-conflict and post-disaster situations, nor for advocates of community greening. We don’t portend to communicate that community greening is a ‘panacea’. At the same time we want to give voice to post conflict planners in military and development assistance agencies, in urban community development contexts, and among post-disaster first responders who recognize the role that humans’ relationship with nature plays in survival situations, when the threat of loss of life, of home and hearth is real and looms large, or after disaster strikes when one is trying to put the pieces back together again. We ask the reader to imagine what would it be like if an approach existed that one could implement in post-conflict or post-disaster scenarios that simultaneously restored individual and community morale, engaged survivors in collaborative asset-based community planning and development, put people on the path to food security, provisioned ecosystem services, and restored the social-ecological balance in symbolic and real ways, all while creating positive feedback loops and virtuous cycles that trend towards desirable resilient states? Impossible one might say. Yet there are examples of community greening in red zones doing exactly this in Sarajevo and Hiroshima, in New Orleans and New York City, and in smaller communities around the globe. Examples where the power of people acting together to restore their homes and neighborhoods with something alive, something green, has had seemingly transformative effects.

The evidence for our thesis about a role for greening in fostering resilience at multiple levels in red zones comes from two sources. First, we present a series of chapters grouped together as ‘motives and explanations’, which draw largely on existing theoretical and applied work to propose conceptual arguments for greening as a disaster response. This section includes Tidball’s chapter on urgent biophilia, which argues that there may be a genetic basis for turning to green during times of insecurity, and Stedman and Ingall’s chapter proposing that a greening response can also be explained by ‘topophilia’, as a reaction to destruction of a landscape that individuals and communities have developed an attachment to over time. Other chapters in this section outline greening in red zones from a historical perspective, including the chapter by Geisler (Chap. 16), which takes us all the way back to the granting of land as a means of empire building during Roman times, and the contribution by Lawson (Chap. 14) who finds that national gardening efforts during wars fought by the US can be explained not just as an effort to increase food production, but also as an expression of patriotism and the need for recreation and restoration during times of stress. We outline the core arguments in each of the motivations and explanations chapters in Table 1.1.

The second type of support for greening as a response to crisis comes from the section entitled case studies, and from the 11 short chapters scattered throughout the book. These examples range from highly visible and symbolic initiatives such as the greening of the Berlin Wall (Cramer, Chap. 34) and plans for converting the Korean Demilitarized Zone into a national biodiversity reserve (Grichting and Kim, Chap. 15), to smaller-scale efforts like planting a community garden as a means of community resilience following war (Winterbottom, Chap. 30). Some examples cross scales—the datcha gardens in post-Soviet Russia were an important source of human resilience and food security, whose community resilience implications were recognized by the Russian government when it enacted a law that converted ownership of the datcha plots from the state to the gardeners (Boukharaeva, Chap. 26). Importantly, a number of the descriptive chapters explore the boundaries between greening in the red zone and related environment-based responses to conflict and disaster. For example, efforts to use management of a common wildlife resource as a means to restore peace among warring ethnic groups in Kenya (Craig, Chap. 28), agroforestry programs in Afghanistan (Thompson, Chap. 9), and the efforts to create Afghanistan’s first national park (Smallwood, Chap. 21), while encompassing the community and environmental values of greening, are perhaps first and foremost focused on sustaining livelihoods or creating protected areas in a fledgling or fragile democracy. Similarly, the green recreation activities described in the chapter by Krasny et al. (Chap. 13) are originally conceived of as a means to foster reintegration of American and British veterans following the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, yet have implications for community resilience. Taken together, the case study and short descriptions represent a wealth of post-disaster and post-conflict greening activities, which allows comparisons and opportunities for reflection about the appropriateness of various practices to the range of red zone settings with which we are confronted as citizens, scholars, and policy makers.

In summarizing these case study and short descriptive chapters, we draw from Carpenter et al.’s (2001) challenge to address the questions: ‘resilience of what? to what?’ For example, are we concerned about the psychological resilience of a child in a war zone? The ability of the forest embedded in a larger urban SES to respond to flooding? To these questions we add, what is the greening response? Thus, Table 1.2 (case studies) and Table 1.3 (short chapters), briefly describe the context and greening response for each chapter.

We invite the reader to not only join in a consideration of the material shared by the contributors to this volume, but also to reflect on his or her own experiences with greening in the red zone. As authors and editors immersed in the discussion, we are constantly reminded of the role of greening in our own resilience and that of other human, social, and ecological systems. As individuals, we derive strength from gardening or tree-planting and from our work with neighbors and students to steward green spaces. As we travel, we are constantly reminded of greening in red zones—whether it be Keith’s recent trip to view the memorial to trees that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, or Marianne’s visit to Anzac Cove in Turkey, where trees were recently planted next to stones memorializing the soldiers who lost their lives during the allied invasion at Gallipoli. As we all are faced with both small and larger red zones, we invite you to join in greening as a response.

Notes

- 1.

See ‘Earth Summit: Messages from the Mountain of Hope Summit Diary’, The Birmingham Post (England), September 2, 2002.

- 2.

Following from the work of Berkes, Colding, and Folke, social systems of primary concern for this volume include myriad property rights, governance, access and use of resources systems in post-disaster and post-conflict contexts, as well as different systems of knowledge relative to the dynamics of environment and resource use, worldviews and the ethics systems concerning human and nature relationships. Ecological systems refer to self-regulating communities of organisms interacting one with another and with their environment. Our emphasis is on the integrated concept of ‘humans-in-nature’, so we use the term social-ecological systems, and agree that social and ecological systems are inextricably entwined, making delineations between social and natural systems artificial and arbitrary. See Berkes et al. (2003) and Berkes and Folke (1998).

- 3.

For an overview of green political thought, see http://www.greenparty.org/ and http://www.global.greens.org.au/charter/10values(us).html

- 4.

Vincent was tragically murdered in Basra, Iraq while reporting on the increasing infiltration of the Basra police force by Islamic extremists loyal to Muqtada al Sadr. See http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/03/international/middleeast/03cnd-iraq.html?_r=1

- 5.

References

Armstrong, D. (2000). A survey of community gardens in upstate New York: Implications for health promotion and community development. Health and Place, 6(4), 319–327.

Berkes, F., & Folke, C. (Eds.). (1998). Linking social and ecological systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berkes, F., Colding, J., et al. (2003). Navigating social-ecological systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bernard, B. (2004). Resiliency: What have we learned? San Francisco: WestEd Publishers.

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: How we have underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events. The American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28.

Bowen, G. L, Martin, J. A, Mancini, J. A., & Nelson, J. P. (2001). Civic engagement and sense of community in the military. Journal of Community Practice, 2001(2), 71–93.

Bowen, G. L, Mancini, J. A, Martin, J. A, Ware, W. B., & Nelson, J. P. (2003). Promoting adaptation of military families:an empirical test of a community practice model. Family Relations, 52(1), 33–44.

Carpenter, S., Walker, B., Anderies, J. M., & Abel, N. (2001). From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems, 4, 765–781.

Clout, H. (1996). After the ruins: Restoring the countryside of northern France after the Great War. Exeter: Short Run Press.

Coser, L. (1992). Introduction on collective memory (pp. 1–34). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Department of Defense. (2005). Military support for stability, security, transition, and reconstruction (SSTR) operations 3000.05. D. o. Defense.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S., et al. (2002). Resilience and sustainable development: Building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations (p. 34) The Environmental Advisory Council to the Swedish Government. Johannesburg, South Africa.

Folke, C., Colding, J., & Berkes, F. (2003). Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. In F. Berkes, J. Colding, & C. Folke (Eds.), Navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Fredrickson, B., Tugade, M., et al. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376.

Ganyard, S. T. (2009, May 18). All disasters are local. The New York Times.

Gunderson, L. H., & Holling, C. S. (Eds.). (2002). Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Gunn, C. A. (1994). Tourism planning: Basics, concepts, cases (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C: Taylor & Francis.

Huebner, A. J., Mancini, J. A., Bowen, G. L., & Orthner, D. K. (2009). Shadowed by war: Building community capacity to support military families. Family Relations, 58, 216–228.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Towards an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 169–182.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Krasny, M. E., & Tidball, K. G. (2010). Civic ecology: Linking social and ecological approaches in extension. Journal of Extension, 48(1).

Krasny, M. E., & Tidball, K. G. (2012). Civic ecology: A pathway for Earth Stewardship in cities. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 10(5), 267–273.

Kuo, F. E., Sullivan, W. C., Coley, R. L., & Brunson, L. (1998). Fertile ground for community: Inner-city neighborhood common spaces. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(6), 823–851.

Light, A. (2003). Urban ecological citizenship. Journal of Social Philosophy, 34(1), 44–63.

Longstaff, P. H. (2005). Security, resilience, and communication in unpredictable environments such as terrorism, natural disaster, and complex technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Program on Information Resources Policy.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., Vol. 3). New York: Wiley.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., et al. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562.

Masten, A. S., & Obradovic, J. (2008). Disaster preparation and recovery: Lessons from research on resilience in human development. Ecology and Society, 13(1), 9.

McIntosh, R. J., Tainter, J. A., & McIntosh, S. K. (Eds.). (2000). The way the wind blows: Climate, history, and human action. New York: Columbia University Press.

Milani, B. (2000). Designing the green economy: The post-industrial alternative to corporate globalization. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., et al. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 127–150.

Olick, K. J., & Robbins, J. (1998). Social memory studies: From collective memory to the historical sociology of mnemonic practices. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 105–140.

Pearce, D. W., Markandya, A., et al. (1992). Blueprint for a green economy. London: Earthscan.

Pendall, R. (1999). Do land-use controls cause sprawl? Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 26(4), 555–571.

Pickett, S. T. A., Cadenasso, M. L., et al. (2004). Resilient cities: Meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landscape and Urban Planning, 69, 369–384.

Saldivar, L., & Krasny, M. E. (2004). The role of NYC Latino community gardens in community development, open space, and civic agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 21, 399–412.

Schmelzkopf, K. (1995). Urban community gardens as contested spaces. Geographical Review, 85(3), 364–381.

Schmelzkopf, K. (1996). Urban community gardens as contested space. The Geographical Review, 85, 364–380.

Smith, C. H., & Hill, C. R. (1920). Rising above the ruins in France: An account of the progress made since the armistice in the devastated regions in re-establishing industrial activities and the normal life of the people. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons.

Taylor, M. (1986). Learning for self-direction in the classroom: The pattern of a transition process. Studies in Higher Education, 11(1), 55–72.

Tidball, K. G., & Krasny, M. E. (2007). From risk to resilience: What role for community greening and civic ecology in cities? In A. E. J. Wals (Ed.), Social learning towards a more sustainable world (pp. 149–164). Wagengingen: Wagengingen Academic Press.

Tidball, K. G., & Krasny, M. E. (2011). Toward an ecology of environmental education and learning. Ecosphere 2:art21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES10-00153.1.

Tidball, K. G., Krasny, M., et al. (2010). Stewardship, learning, and memory in disaster resilience. Environmental Education Research, 16, 591–609.

Tidball, K. G., & Weinstein, E. D. (2011). Applying the environment shaping methodology: Conceptual and practical challenges. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 5(4), 369–394.

Tukey, H. B., Jr. (1983). Urban horticulture: Horticulture for populated areas. Horticultural Science, 18(1), 11–13.

Ulrich, R. (1993). Effects of exposure to nature and abstract pictures on patients recovering from open heart surgery. Journal of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, 30, 204–221.

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224, 420–421.

Vincent, S. (2004). In the red zone: A journey into the soul of Iraq. Dalls: Spence Publishing Company.

Weinstein, E., & Tidball, K. G. (2007). Environment-shaping: An alternative approach to applying foreign development assistance. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 1(1), 67–85. doi:10.1080/17502970601075923.

Wells, N., & Evans, G. (2003). Nearby nature: A buffer of life stress among rural children. Environment and Behavior, 35(3), 311–330.

Wright, M. O., & Masten, A. S. (2005). Resilience processes in development: Fostering positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 17–37). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Zautra, A. J. (2003). Emotions, stress, and health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tidball, K.G., Krasny, M.E. (2014). Introduction: Greening in the Red Zone. In: Tidball, K., Krasny, M. (eds) Greening in the Red Zone. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9947-1_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9947-1_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-90-481-9946-4

Online ISBN: 978-90-481-9947-1

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)